Worcestershire was the county where the first battle and last battle of the English Civil War took place. The first battle, the Battle of Powick Bridge, fought on 23 September 1642, was a cavalry skirmish and a victory for the Royalists (Cavaliers). The final battle, the battle of Worcester, fought on 3 September 1651, was decisive and ended the war with a Parliamentary (Roundhead) victory and King Charles II a wanted fugitive.

During the First Civil War the county was under the control of the Royalists although many of their fortified garrisons were besieged by Parliamentarian forces at one time or another. For example, Worcester was besieged twice before finally surrendering on 23 July 1646. After the surrender many Royalist families in Worcestershire had their estates sequestered and had to compound (pay a fine to buy back their property) calculated in part by the expected income from their estate and also by their involvement in the Royalist cause during the civil war.

Other than the Broadway Plot of January 1648 the events of the Second English Civil War (1648) passed Worcestershire by.

During Third English Civil War Charles II lead a predominantly Scottish Royalist army to the City of Worcester hoping that English Cavaliers would rally to his banner. While a few did, Charles's army was surrounded by a much larger Parliamentary army under the command of Oliver Cromwell and comprehensively defeated in what Cromwell described as a "Crowning Mercy".

Prelude to war

Charles I's policies of rule without Parliament forced him to raise taxes on imports of goods known as 'tonnage and poundage'. Policies like these particularly reduced the profitability of trade and created opposition in urban centres including Worcester. Similarly, the Ship Money taxation levied in 1636 fell heavily on Worcester, which was the sixteenth highest paying city in England. Puritans including Richard Baxter noted the mounting opposition to Royal policies within the county. The unpopularity of these Royalist policies stemmed from the perception that Charles I was attempting to establish a more authoritarian, non-Parliamentary kind of monarchy.[1]

Worcestershire had also seen a number of divisive enclosure schemes during Charles' reign, including attempts to enclose Malvern Chase and the more successful sale of Feckenham Forest in the 1630s, which in both cases had led to rioting as well as the displacement of the rural poor that had depended on the use of these Royal lands as effectively common land, with long-established although informal usage rights.[2] Other local grievances against the Crown included action to suppress profitable tobacco production, which was well established in the Vale of Evesham.[3]

Charles I was simultaneously pursuing religious policies that provoked suspicion in Worcestershire. Although the county had a Catholic minority among its aristocratic families, the rest of the population was firmly Anglican, with a growing group of more radical Protestants in some of its northern towns, such as Kidderminster. Charles' apparent Catholic sympathies, such as the reforms of William Laud that reintroduced many of the trappings of Catholicism back into the Church of England, would have been viewed with suspicion by many. In the early 1640s, stories of massacres of Protestants in Ireland helped lead to rumours of Catholic plots that spread through the county leading to anti-Catholic riots in Bewdley in late 1641, and instructions to local militias to guard against conspiracies in the following months.[3]

Outbreak of the war

Like many parts of England, there was little enthusiasm for either side, and the initial instincts of many was to try to avoid conflict. Different parts of the county had different sympathies, for instance Evesham was notably Parliamentarian, and Kidderminster also had a strong Parliamentarian contingent.

The immediate cause of the war was a struggle between Parliament and the Crown to control of the country's armed forces, the Trained Bands, which were ordinarily under the control of the crown. A split between the county's aristocratic families, who helped organise Royalist control of the Trained Bands, and the city of Worcester, which attempted to gain control its own forces from the county from 1641, can also be seen.[4]

Nevertheless, the city of Worcester equivocated about whether to support the Parliamentary cause immediately before the outbreak of civil war in 1642, raising its own independent and neutral armed forces in June.[5] Royalists started organising military forces at the Town Hall in mid July, but the city council then sided with Parliament, after the Worcestershire MPs Humphrey Salway and John Wylde returned to galvanise the city against Royalist control. A Grand Jury then declared the King's Commission of Array illegal, and gathered signatures in support of Parliament's Militia Ordinance.[5]

Royalist gentry from across Worcestershire continued to organise the Trained Bands for the King, however, and organised a support of a Grand Jury in early August that ordered the arrest of leading Parliamentarians and summoned the Trained Bands to Pitchcroft on 12 August. The quality of the troops was however rather low, with makeshift armaments and supplies.[6] When the forces were summoned again at the outbreak of war on 22 August, just 500 men were present, a much lower figure than might be expected, suggesting a lack of enthusiasm for either side and desire to avoid the conflict if possible.[7]

Around the same time a Parliamentary force was moving from London to secure Coventry and Warwick. the Royalist trained bands of Warwickshire requested help from Worcestershire, but did not receive it, as the Commissioner did not wish to force his troops to serve outside the county against their expectations. Even at this very early stage, the tension between the localised Royalist military structures and the need for a national fighting effort could be seen.[6]

Royalist control of Worcestershire

The numbers of Worcester gentry that were active Royalist military and civilian leaders was quite small. Atkin calculates that around 25 individuals made up the core of the Royalist organisers in the country. 44 were arrested at the end of the war. Both are much lower numbers than the size of the gentry class, suggesting that most people tried to keep out of the conflict as best they could.[8]

Worcester and the county was more or less under Royalist control at the start of the conflict. The cathedral was used to store arms during the war, possibly as early as September 1642.[9] Royalists were using the building to store munitions when Essex briefly retook the city after the Powick Bridge skirmish on its outskirts. Parliamentary troops then ransacked the cathedral building. Stained glass was smashed and the organ destroyed, along with library books and monuments.[10]

Worcester, Dudley and Hartlebury were Royalist garrisons in the county. Worcester in particular had to bear the expense of sustaining and billeting a large number of Royalist troops. During the Royalist occupation, the suburbs were destroyed to make defence easier. Responsibility for maintenance of defences was transferred to the military command. High taxation was imposed, and many male residents impressed into the army.[11] Towards the end of the war, the number of people within Worcester who were on poor relief had risen dramatically, while trade and commerce had declined.

The same pressures created great strain on the county as a whole, as it had to sustain a large, unproductive force drawn out of its productive labour.[12] An illustration of these taxes, levied by both sides over a period of time, can be seen in Elmley Lovett.[13] Taxation was heavy and requisitioning by armies could be particularly debilitating. At times, reprisals could be very harsh. In 1643, for instance, Royalist troops used physical violence and deliberately destroyed pea and bean crops at Amscote and Treadington when residents tried to resist their demands. The Royalist horse regiments stripped much of northern Worcestershire of produce to the extent that Droitwich, Bromsgrove, King's Norton, Alvechurch and Abbots Morton were unable to pay their tax demands.[14]

The proximity of Worcestershire to Parliamentary forces to the north around Birmingham, to the east in Warwickshire, and at certain times to the south in Bristol and Gloucestershire, made the county vulnerable to raiding and requisitions.[15]

Nevertheless, the county was strategically vital to the Royalists, as a bridge from their mostly Western territories including Wales and Ireland back to their headquarters in Oxford.[16] Worcestershire also provided the Royalists with industrial capacity to produce armaments and munitions.[17]

In June 1644, General William Waller's force of around 10,000 men pursued the King's army into Worcestershire as it retreated from Oxford. Waller was supported by the residents of Evesham, who repaired their bridge which had been broken to slow his passage into Worcestershire; the town was heavily fined and the Mayor George Kempe arrested after Waller withdrew. Waller's army during June lived off whatever they could requisition, first in the Vale of Evesham, then Bromsgrove and Kidderminster. After failing to take Bewdley, they occupied Droitwich before returning to Evesham. Parts of Waller's force was ill-disciplined, and the line between requisitioning and simple theft became unclear. After Waller had left, the Royalist army in the vale of Evesham was forced to bring in supplies from outside, for instance Bridgnorth and Shropshire, because of the scale of requisitioning.[18]

The Scottish army that entered Worcestershire in 1645 gained a particularly bad reputation, reflected in claims made to the Exchequer after the war. They seem to have taken whatever sheep they could and plundered items as diverse as clothing, household items, wagons, brooches and food. There were also claims of widespread destruction of crops as they advanced.[14]

The Royalist Hartlebury garrison also gained a bad reputation for sequestrating local supplies and thereby depleting the neighbouring area through the war.

Bands of Clubmen formed in west Worcestershire in the later part of the first war, with the objective of keeping both armies and their demands away from the rural civilian population, to resist despoliation and requisitioning. There was also a vein of resentment towards the prominent role given many Catholics in the county. The Clubmen's Woodbury Hill proclamation stated that they would not obey any Papist or Papist Recusant, "nor ought [they] … be trusted in any office of state, justice, or judicature".[19]

As Royalist power collapsed in May 1646, Worcester was placed under siege. Worcester had around 5,000 civilians, together with a Royalist garrison of around 1,500 men, facing a 2,500–5,000 strong force of the New Model Army. Worcester finally surrendered on 23 July, bringing the First Civil War to a close in Worcestershire.[20] At the surrender of the city, the Royalist leaders were forced to swear that they would not fight against Parliament again, a promise that a number of them broke in 1651.[21]

Scottish troops and the Third Civil War

In 1651 a Scottish army marched south along the west coast in support of Charles II's attempt to regain the Crown and entered the county. The 16,000 Scottish force caused Worcester's council to vote to surrender as it approached, fearing further violence and destruction. The Parliamentary garrison decided to withdraw to Evesham in the face of the overwhelming numbers against them. The Scots were billeted in and around the Worcester, again at great expense and causing new anxiety for the residents. The Scots were joined by very limited local forces, including a company of 60 men under John Talbot.[22]

The Battle of Worcester (3 September 1651), took place in the fields a little to the west (near the village of Powick) and south of the city. Charles II's army was easily defeated by Cromwell's forces of 30,000 men.[23] Charles II returned to his headquarters in what is now known as King Charles House in the Cornmarket,[24] before escaping north out of the county, and eventually on to France, aided by a number of Worcestershire's Catholic gentry.[25]

In the aftermath of the battle, Worcester was heavily looted by the Parliamentarian army, with an estimated £80,000 of damage done, and the subsequent debts still not recovered into the 1670s. The Scottish troops that were not captured meanwhile were attacked by locals as they fled. Around 10,000 prisoners, mostly Scots, were held captive, and either sent to work on the Fens drainage projects, or transported to the New World to work as forced labour.[26]

Timeline

This is a timeline for the English Civil War in Worcestershire.[27]

First English Civil War

1642. King Charles I moved from Nottingham to Shrewsbury. The Earl of Essex, who commanded the Parliament army, was ordered to prevent the King advancing on London, so marched from Northampton to Stratford-on-Avon, Pershore to Worcester. shortly before Essex arrived at Worcester, the first major cavalry skirmish took place in at Powick Bridge. Charles, having completed his preparations, marched by Wolverhampton, Birmingham, towards Banbury, thus getting between Essex and London. Turning round, he defeated Essex at the Battle of Edgehill, and slowly marched on towards London, before turning after the Battle of Brentford retreating first to Reading and then to Oxford. The result of the advance by the Royalists towards London was that the Parliament troops evacuated Worcestershire.[28]

1643. The King established his headquarters at Oxford, and was most anxious to win the highlands of the Cotswolds and the line of the river Severn. The Parliamentarians had two armies. Their plan was that the two armies, one of which was engaged before Reading under Essex, the other under William Waller had its headquarters at Bristol, should unite and take Oxford. Essex took Reading. Waller, operating from Gloucester, cleared the county, and by taking Hereford cut off communication with Wales. To make all safe in the Severn Valley, Charles besieged Gloucester, but Essex was able to raise the siege.[28]

1644. Again Parliamentary forces tried the same plan as the previous year. Essex and Waller were to join and march on Oxford. They did so, and very nearly caught Charles I, but he escaped, marched by Broadway to Evesham, Pershore to Worcester, and on to Bewdley. Waller followed him, but the two armies did not come to close quarters; the only fighting was Wilmot's attempt to relieve Dudley Castle, which was being besieged by Lord Denbigh. Charles retired towards Oxford, followed by Waller, who was defeated by Wilmot at the Battle of Cropredy Bridge. Charles then returned into Worcestershire, and stayed at Evesham for some days.[28]

1645. Edward Massey, the Governor of Gloucester, stormed and took Evesham, thus severing the Royalist line of march from Worcester to Oxford. Charles marched to Inkberrow, Droitwich, Bromsgrove, and on to Leicester and then to Naseby, where he was defeated; then back by Kidderminster, Bewdley to Hereford and South Wales. The Scottish army came to the help of the English, and marched to Alcester on their way to attack Worcester, but turned off to Droitwich, Bewdley, and so to Hereford, which they besieged. Charles marched north, and working round reached Oxford. Having got some troops together, he marched to the relief of Hereford. He stayed several days in Worcester, marched from there to Bromyard and on to Hereford, but on his approach the Scotch raised the siege, marched to Gloucester, crossed the Severn, then marching through Cheltenham, Evesham, to Stratford-on-Avon on their way towards Newark.[29]

1646. During the winter a Royalist army was collected in Wales, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire, and marched towards Oxford, but were met by the Parliamentary troops near Stow-on-the-Wold and destroyed. Shortly after this Charles left Oxford and gave himself up to the Scots. He issued orders to his captains and officers to deliver up the places they held. Dudley Castle surrendered, as did Hartlebury. Worcester was besieged and held out to July when it had to surrender. Included in the Articles were Madresfield and Strensham. With their surrender the First Civil War, so far as Worcestershire was concerned, came to an end.[30]

Second Civil War

1647. During the whole of the year Royalist plots went on to bring about the King's release, or for a rising. The chief of these was the Broadway Plot.[30]

1648. The Royalist plot, ended in the second Civil War, the chief feature in which was the siege of Colchester. An attempt at a rising, organised by Colonel Dud Dudley, was made in Worcestershire, but it was suppressed, Dudley taken prisoner, sent to London, and condemned to die. The morning before his execution he escaped.[30]

1649. King Charles I was executed. Charles II went to Scotland and was proclaimed King of Scotland. The Parliament troops were engaged in putting down the Irish.[30]

Third Civil War

1650. Oliver Cromwell, having finished off the Irish, went to Scotland and defeated Leslie and the Scots at the Battle of Dunbar.[30]

1651. After a good deal of negotiations and manoeuvres Charles II, at the end of July, invaded England, marching through Carlisle on London. When he got to Stafford it was thought desirable to halt for reinforcements from Wales, and to meet these men Charles marched to Worcester. Cromwell, meanwhile proceeded down the east coast, marched across to Evesham, thus getting between Charles and London, advanced on to Worcester, attacked and routed him at the Battle of Worcester.[30]

See also

Notes

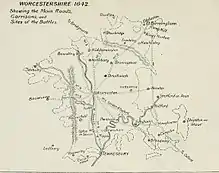

- ↑ The six roads numbered on the map are the important thoroughfares that linked Worcester with the rest of the country:[lower-alpha 2]

(1.) The Oxford and London Road. This entered the County near Honeybourne, passed through Bretforton, over the Avon at Offenham at Twyford Bridge, where Offenham Boat is now, then through Norton, Wyre, Pinvin, White Ladies' Aston, Spetchley, Red Hill, to Worcester. This is and was the direct road from Worcester to Oxford, and by it all convoys of supplies and all detachments of recruits would have to pass.

(2.) At Worcester this road divided, one branch to the right is the road to the north, spoken of, near Birmingham, as the " Bristol Road." It crossed Barbourne Bridge and went to Droitwich, Bromsgrove, over the Lickey to Northfield, and passed out of the County into Warwickshire at Bourn Brook.

(3.) Another branch, also going to the north, after crossing Barbourne Bridge, went to the left through Ombersley and Hartlebury; here it again branches off the road to the right, going through the parishes of Chaddesley Corbett and Belbroughton, past Hagley and Pedmore to Stourbridge into Staffordshire. This is the road by which Charles II went after the Battle of Worcester. The road to the right at Hartlebury passed through Kidderminster, and so on to Bridgnorth.

(4.) The road crossing the Severn at Worcester, and going by Kenswick, Martley, crossing the Teme at Ham Bridge, through Clifton-on-Teme to Tenbury, and then into Shropshire. On this road is the Tenbury Bridge over the Teme. When this was damaged in 1615, the town of Tenbury asked the Sessions to help to repair it, as it was "the great thoroughfare from most places in Wales to the City of London."

(5.) The road from Worcester crossing the Severn, proceeding by Cotheridge, Broadwas, across the Teme at Knightsford Bridge, and so on to Bromyard, thence to Hereford and Wales. Along this road the troops sent with Lord Stamford to occupy Hereford in 1642 returned, and Charles I marched along it to relieve Hereford in 1645.

(6.) The road from Worcester going south along the east bank of the river (the Bath) road, passing through Kempsey, Severn Stoke, to Tewkesbury and Gloucester. It was along this road Waller advanced to attack Worcester in 1643.

There were other important roads, but they were more of local importance, or else served as alternative routes. - Willis-Bund 1905, p. 8.

References

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 29–30

- ↑ Lees 1877, pp. 16–17; Sharp 1980

- 1 2 Atkin 2004, p. 30

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 34–36

- 1 2 Atkin 2004, p. 36

- 1 2 Atkin 2004, pp. 40–44

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 46–47

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Atkin 2004, p. 50

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 52–53

- ↑ Atkin 2004

- ↑ Atkin 2004, p. 101

- ↑ Diary of Henry Townshend (1625 – 1682) of Elmsley Lovett https://hdl.handle.net/2027/yale.39002006115324 https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002006115324&view=1up&seq=4 Yale University

- 1 2 Atkin 2004, p. 100

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 100–106; on strategic position see Atkin 2004, pp. 108–106 and Atkin 2004, pp. 61–64

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 60–62; Lloyd 1993, p. 73

- ↑ Atkin 2004, p. 60

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 94–99

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 117–20

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 125–7

- ↑ Lloyd 1993, p. 77

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 142–143

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 142–147

- ↑ Atkin 2004, p. 146

- ↑ Atkin 2004, p. 144

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 144–147

- ↑ Atkin 2004, pp. 8–10

- 1 2 3 Willis-Bund 1905, p. 1.

- ↑ Willis-Bund 1905, pp. 1, 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Willis-Bund 1905, p. 2.

Sources

- Atkin, Malcolm (2004). Worcestershire under arms. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-072-4. OL 11908594M.

- King, Peter (July 1968), "The Episcopate during the Civil Wars, 1642–1649", The English Historical Review, Oxford University Press, 83 (328): 523–537, doi:10.1093/ehr/lxxxiii.cccxxviii.523, JSTOR 564164

- Lees, Edwin (1877), The Forest and Chase of Malvern, Transactions of the Malvern Naturalists' Field Club, pp. 16/17

- Lloyd, David (1993), A History of Worcestershire, Chichester: Phillimore, ISBN 978-0850336580

- Sharp, Buchanan (1980), In contempt of all authority, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-03681-9, OL 4742314M, 0520036816

Attribution

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Willis-Bund, John William (1905). The Civil War in Worcestershire 1642-1646 and the Scotch invasion of 1651. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Company.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Willis-Bund, John William (1905). The Civil War in Worcestershire 1642-1646 and the Scotch invasion of 1651. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Company.

Further reading

- Atkin, Malcolm (1995). The Civil War in Worcestershire (illustrated ed.). Alan Sutton Pub. ISBN 9780750910507.

- Atkin, Malcolm (2007). "Civil War archaeology". In Brooks, Alan; Pevsner, Nikolaus (eds.). Worcestershire. Pevsner Architectural Guides: The Buildings of England (illustrated, revised ed.). Yale University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780300112986.

- Atkin, Malcolm (2008). Worcester 1651. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-080-9.