| Zhengao | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

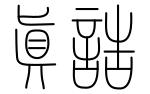

Seal script for Zhengao | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 真誥 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 真诰 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | true proclamation | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 진고 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 眞誥 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 真誥 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | しんこう | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

The Zhengao (真誥, Declarations of the Perfected) written in 499 CE is the Shangqing Daoist patriarch Tao Hongjing's comprehensive collection of poetry and prose from the original "Shangqing revelations", which were supposedly given to the mystic Yang Xi by a group of Daoist zhenren Perfected Ones from 364 to 370. This classic text has long been famous both as a foundational text of religious Daoism and as a brilliant exemplar of medieval Chinese poetry.

History

The Zhengao is a compendium of Shangqing Daoist materials transmitted by the Eastern Jin dynasty scholar and mystic Yang Xi (330-c. 386) and his patrons Xu Mi (許谧, 303-376) and Xu Hui (許翽, 341-c. 370). The large, aristocratic Xu (許) family was from Jurong, Jiangsu, which was the Eastern Jin capital Jiankang (modern Nanjing) from 317 to 420. Following the Xu family tradition of government service, Xu Mi and his son Hui were officials in the court of Emperor Ai, unlike Xu Mi's elder brother Xu Mai (許邁, 300-348) who converted to the Way of the Celestial Masters, resigned from his official career and devoted himself to Daoist studies and practices. In 362, the Xus employed Yang Xi as their household shaman and spiritual advisor, and two years later when he first established contact with the Perfected Ones from the previously unknown heaven of Shangqing (上清, Highest/Supreme Clarity), they prophesied that the Xu family would have an important role in transmitting the prophetic revelations.[1]

According to Shangqing School tradition, between 364 and 370, Yang Xi had a series of midnight visions in which Perfected Ones appeared to him in order to reveal their sacred scriptures, talismans, and secret registers, as well as their instructions concerning personal matters such as health and longevity.[2] Yang wrote down the content of every vision in ecstatic verse, recording the date along with the name and description of each Perfected who appeared. The purpose of the revelations was to set up a new syncretic faith that claimed to be superior to all earlier Daoist traditions.[3] Most texts revealed by Yang Xi were intended for the family patriarch Xu Mi, his relatives, and friends.

The visions appeared to Yang Xi alone, and he said the Perfected directed him to transcribe the revelations for transmission to Xu Mi and Xu Hui, who would make additional copies.[4] The Zhengao says the Perfected women told Yang that since they could not express themselves in debased human writing, he would act as an intermediary, rendering their words in his own outstanding calligraphy. After each transmission the Perfected checked that he transcribed their words correctly and then "presented" it back to him as if they had written it themselves.[5] The heavenly maidens who visited Yang at night "never write themselves, neither with their hands nor with their feet", but instead would take his hand and engage him in a "sublime relationship" while he transcribed the sacred texts[6]

The Perfected who appeared to Yang Xi constituted three groups.[7] The first were early saints in the Shangqing movement. The three brothers Mao Ying (茅盈), Mao Gu (茅固), and Mao Zhong (茅衷), referred to as the Three Lords Mao, supposedly lived in the Western Han dynasty. Perfected Lady Wei Huacun (252-334), a Way of the Celestial Masters adept proficient in Daoist meditation techniques was among the Perfected, and she became Yang's xuanshi (玄師, Teacher in the Invisible World).[8] Another notable example is the legendary xian transcendent Zhou Yishan (周義山, b. 80 BCE). The second group includes Yang Xi's bride, the Perfected Consort An (安妃), the Ninefold Florescent Perfected Consort in the Upper Palace of Purple Clarity, and her mythological parents Master Redpine and Lady Li (李夫人). The third are the Queen Mother of the West's daughters, such as the Lady of Purple Tenuity (紫微夫人) who served as matchmaker between Yang Xi and Consort An.

After Xu Mi died in 376, Xu Hui's son Xu Huangmin (許黄民, 361-429) spent several years compiling all the available Yang-Xu transcribed texts. He first distributed copies among the Xu family and their friends. Early readers of these revealed texts were impressed both by the erudite literary style of ecstatic verse and the artistic calligraphy of Yang Xi and Xu Hui.[9]

Manuscripts concerning the Shangqing revelations later were collected by several eminent Daoists. Notably, Gu Huan (顧歡, c. 425-c. 487) edited a compilation of Yang-Xu texts entitled Zhenji (真跡, Traces of the Perfected), which became the model for Tao Hongjing's 499 Zhengao. Tao's postface notes differences between the two collections of Yang-Xu manuscripts. The Zhenji includes secondary texts such as biographies of the Daoist hermit Xu Mai by his famous calligrapher friends Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi, while the Zhengao is restricted to the revealed texts and their historical context. Gu's work was composed of facsimile tracings of the manuscripts, while Tao's more accessible work included his calligraphic analysis of who wrote each component text.[10]

The eminent Shangqing scholar and alchemist Tao Hongjing (456-536) collected, annotated, and redacted all the available autograph fragmentary Yang-Xu manuscripts.[11] Based upon his remarkable familiarity with the calligraphy of Yang Xi, Xu Mi, and Xu Hui, Tao was able to judge authenticity and to eliminate forgeries, resulting in an early example of text-critical scholarship.[1] Tao's painstakingly endeavors resulted in two texts. The esoteric c. 493-514 Dengzhen yinjue (登真隱訣, Concealed Instructions for the Ascent to Perfection), which provides technical guidance for Shangqing adepts, and the 499 Zhengao, which was intended for a broader audience of laypeople.[12]

Tao Hongjing's Zhengao Declarations of the Perfected survives as a complete work, with interpolations and commentarial additions. Standard editions are found in the 1444 Daozang Daoist Canon (CT 1016) and the 1782 Siku Quanshu literary collection. The received text of Zhengao is dated 499, with a preface by Gao Sisun (高似孫) dated 1223.[13]

In English, there are only partial translations of the Zhengao. Bokenkamp[14] translated some prose and seven poems, Kroll translated nine poems,[15] and Schipper[16] two.[17] Smith made an annotated translated of Chapter 1.[18]

In Japanese, there are Zhengao (Shinkō) reference works and a full translation. Ishii (1971–72) and (1987) compiled indexes of the people, places, and titles mentioned in the text, and Mugitani created a concordance.[19] Yoshikawa and Mugitani[20] wrote an annotated translation.[21]

Title

Tao Hongjing titled his book with zhēn (真 or 眞, "real; true; perfected"; as in Gu Huan's Zhenji Traces of the Perfected) and gào (誥 , "proclamation; announcement"), denoting that its contents were divinely inspired. Daoist zhenren "Perfected" deities gao "dictated" the Shangqing revelations to highly literate medium and shaman Yang Xi.[22]

In the historical linguistics of the Chinese language, "Medieval Chinese" was used in texts during the 4th and 5th centuries when the Zhengao was written and compiled. Owing to the significant differences in word meanings between Medieval and Modern Chinese, the following semantic discussion of zhen and gao will summarize English translation equivalents from Paul W. Kroll's dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese.[23]

Zhēn (from Middle Chinese tsyin) (眞 or 真) had complex abstract meanings.

- real, true < true to its own nature; natural, authentic, genuine. … a. what really is supposed to be … b. pure, perfect, of thoroughgoing genuineness … c. realize(d), perfect(ed), actualize or bring to completion one's inherent qualities … d. ideal, worthy to be imitated.

- true < what is real and not illusory … a. consistent with fact or reality … b. accurate; truthful(ness); verity …

- really, actually, truly, indeed. … [24]

The Daoist term zhēnrén (真人) has many English translations such as "Real Person", "Authentic Person", "True Person", "Perfected Person", and "Perfected".[25] Kroll clarifies the difference between Daoist and Buddhist usages: "(1.c.) zhēnrén, Realized Persons, the Perfected, term found as early as the 6th chapter of Zhuangzi and used in various movements, but esp[ecially] influential in Shangqing Dao[ism] to designate the highest class of divine beings whose home is in the Shangqing heaven and who are completely spiritualized."; "(2.) … zhēnrén, "one who embodies truth," [transcription] of Sanskrit arhat…

Chinese zhēn "real; true; genuine; etc." is written with several variant characters in East Asian languages, illustrating the Unicode compatibility difficulties with encoding CJK [Chinese, Japanese, and Korean] characters.

The early graph 眞 (U+771E) is now an outdated traditional Chinese character, Korean hanja, Vietnamese Chữ Nôm, and Japanese kyūjitai ("old character form") kanji. There are variations of the calligraphic strokes below the mù 目 "eye" component in 眞. This 10-stroke 眞 graph has a single "down and right" pattern (cf. 乚); which the 11-stroke 眞 (U+2F945) replaces with a 2-stroke "down and stop, right" version.

The modern 真 is both the traditional and simplified Chinese character, and the Japanese shinjitai ("new character form"). Note the change of the original bǐ 匕 "spoon" at the top of 眞 (compare the Small seal script in the infobox above) to shí 十 "ten". There are Sino-Japanese variations on the horizontal line below the 目 "eye" element; Chinese 真 (U+771F) connects it with the horizontal line, while Japanese 真 (U+2F947) separates them.

Gào (Middle Chinese kawH) 誥 had comparatively more concrete semantics.

- proclaim, proclamation; announce(ment); from med[ieval] times exclusively superior to inferior. … a. royal proclamation conferring noble title or special recognition; entitlement.

- exhortation; advisory instruction to subordinate, monition.

- oracle, announcement from a divinity.[26]

The traditional Chinese character 誥 or simplified 诰 is classified as a radical-phonetic character, composed from the "speech" radical yán 言 and a gào (MC kawh or kowk) 告 "announce, proclaim; report; exhort; accuse" phonetic element.

Scholars either transliterate the title (Zhengao, Zhen Gao, Chen-kao, etc.) or translate it:

Content

The Zhengao primarily contains Yang Xi's writings that purport to convey the teachings revealed in his spiritual visions.[33] Tao Hongjing's redacted fragments relate the circumstances of the revelations, the Perfected Ones' explanations and interpretations of their scriptures and methods, private correspondences between Yang and the Xus, and responses to their direct questions addressed to the Shangqing divinities. Tao regularly comments on the authenticity of a text and whether he considered it an original Shangqing fragment.[34] Gao Sisun's preface uses the weaving terms jīng (經, warp) and wěi (緯, weft)—alluding to the literary terms jīngshū (經書, classics; scriptures) and wěishū (緯書, esoteric glosses on the classics) —to describe the Zhengao as the "weft" background of the Shangqing revelations.[12]

Tao Hongjing's received Zhengao is divided into seven piān (篇, chapters) and twenty juǎn (卷, volumes), but this was not the original format. It was initially arranged into ten juan, or ten pian according to some later references. In the present text, chapters 1, 2, and 4 are each split in two parts, making ten chapters altogether, and the arrangement into twenty volumes results from the further subdivision of each chapter into two parts.[1]

Each chapter has a three-character title, emulating the New Text school's apocryphal chènwěi (讖緯, "mystical Confucian prophetical works of Eastern Han").[32] In the table below, chapter 1 and 2 translations are by Smith[18] while the others are tentative.

| Chapter (篇) | Volumes (卷) | Pinyin | Title | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1-4 | Yùn tíxiàng | 運題象 | Setting Scripts and Images into Motion |

| 2 | 5-8 | Zhēn mìngshòu | 甄命授 | Instructions for Shaping Destiny |

| 3 | 9-10 | Xié chāngqí | 協昌期 | Cooperating with Prosperous Times |

| 4 | 11-14 | Jī shénshū | 稽神樞 | Investigating the Spiritual Pivot |

| 5 | 15-16 | Chǎn yōuwēi | 闡幽微 | Revealing the Profoundly Faint |

| 6 | 17-18 | Wò zhēnfǔ | 握真輔 | Grasping the Perfect Assistance |

| 7 | 19-20 | Yì zhēnjiǎn | 翼真檢 | Sheltering the Perfect Standard |

The division into seven chapters resulted from Tao's "sometimes clumsy" effort to give coherence to the whole.[12] The first five chapters record the revelations of the Perfected. Chapter 1 contains texts relating Yang Xi's visions of and hymns sung by the Perfected, and fragments of Ziyang zhenren (紫陽真人, Perfected Purple Yang)'s lost Jianjing (劍經, Scripture of the Sword) with a method for making a magic sword that will provide immortality through shijie (屍解, liberation by means of a simulated corpse).[35] Chapters 2 and 3 are devoted to minor recipes and methods by lesser divinities, with information on the afterlife of the Xus' relatives and acquaintances, and a work revealed to Peijun (裴君, Lord Pei), the Baoshen qiju jing (寶神起居經, Scripture on the Behavior for Treasuring the Spirit).[36] The fourth chapter concerns Maoshan, its long history of mystics and hermits, biographies of the Mao brothers, and Guo Sichao (郭四朝), an early inhabitant of the mountain.[37] The fifth comprises a detailed description of the Chinese underworld, and may have constituted the lost Fengdu ji (酆都記, Records of Fengdu), referring to the subterranean administrative headquarters of hell. Chapter 6 of the Zhengao consists of personal letters, memoranda, and records of dreams written by Yang and the Xus. Tao gives a detailed commentary on the texts contained in these first six chapters. The seventh chapter is Tao's postface, explaining his editorial methods, the history of the Shangqing textual corpus being scattered and plagiarized, and the Xu family genealogy.[38] Despite this overall ordering, some sections have occasional interpolations, repetitions, and misplaced insertions, often resulting in a "confused and truncated" logical order of presentation.[34]

Syncreticism

Scholars have long recognized that much of the Zhengao content derives from a syncretic assortment of older sources from Wu shamanism, Celestial Master Daoism, and Chinese Buddhism, despite the "resplendent homogeneity which originally disparate elements appear to have acquired in his inspired transcriptions".[39]

Wu-shamanist influences

The Shangqing school "succeeded in adhering to a perilous ridgeline" situated between ancient shamanism or mediumship and modern institutionalizing a church and codifying its liturgy.[40] Chinese shamanic spirit journeys are a key literary device in both Zhengao poems and earlier Chuci (Songs of Chu) poems such as Li Sao (Encountering Sorrow), Yuan You (Far-off Journey), Jiu Ge (Nine Songs), and Jiu Bian (Nine Changes). Chinese wu shamans were spirit mediums who practiced divination, prayer, sacrifice, and rainmaking. Many of their practices were later adapted by Daoists.

The Zhengao section recording Yang Xi's and Consort An's betrothal and "spirit marriage" of illustrates how Yang adapted southern shamanic traditions. It resembles Chuci poems where male and female shamans describe their meetings, celestial travels, intercourse with nature spirits, and recount their yearnings once the spirit has gone. The passage is also an explicit renunciation of Celestial Masters marriage rites in which the initial sexual act of a bride and groom was performed ritually in the presence of the elders. The Shangqing spirit marriage between Yang and his celestial Consort also involves the merging of corporeal spirits, but all traces of the human sexual act are absent. Yang Xi names this refined type of spiritual union as oujing (偶景, "mating of the effulgent spirits") rather than the Celestial Master sexual practice of heqi (合氣, "joining of the pneumas").[41]

Ziwei Fujin (紫微夫人), translated as the Perfected Consort of Purple Clarity[14] or Lady of Purple Tenuity,[18] was the celestial matchmaker between Yang Xi and Consort An. In Chinese astronomy, Ziwei (紫微, Purple Clarity) is the name of a constellation near the Pole star that was associated with Destiny in Daoist fortune-telling.[42]

On the night of 26 July 365, the Perfected Consort of Purple Clarity descended to Yang Xi and introduced his stunning bride Consort An. Both Perfected ladies dictated poems to ensure that Yang understood the cosmic significance of their engagement. At their spirit marriage on the next night, Consort An explains their destiny,

It is just that I grasp the crux of things and so seized this rare opportunity, thereby responding to cosmic rhythms and numerological fate. In lowering my effulgent corporeal spirits into the dust and evanescence of your world, I have harnessed them as dragons to plunge below. This was done expressly to summon to me the male who pursues the mysterious and to pursue with him an association wherein I might gain a suitable counterpart. We came together because of predestination. As a result,

Our records were compared, our names verified;

Our immaculate tallies joined in the jeweled realms—

Our dual felicity has been arranged:

We will travel as wild geese supporting one another.

We will share sips from a single gourd-goblet,

Toasting the nuptial quilt and knotting our lower garments.

When you look to your mate for the food she will prepare—

It is the Perfected drugs she holds inside herself. ...[43]

The Zhengao is a unique source for understanding the ancient shamanistic Daoism of Southern China, and its ecstatic poetry shows a distinct relationship to earlier shaman-inspired literature such as in the Chuci anthology. The spiritual quest for "a divine lover who is at the same time a redeemer" is a central theme in the Zhen Gao, and the male and female Daoist adepts exchange love poems with their immortal counterparts, in celebration of their ecstatic union.[2] Take for instance, the "Song of Consort An" that she dictated to Yang Xi.

My chariot has departed from the realm of Western Flowers,

Wandering between the worlds of impermanence and transcendence.

I now look at the summits of the Five Marchmounts,

Then again I bathe myself in the Milky Way.

Leaving my chariot behind, I search for an empty vessel,

In all this I am full of passionate feelings,

Who like a mustard grain can suddenly grow to cover ten thousand acres!

In the center stands Mount Sumeru:

There is no difference between large and small.

The same cause stands at the root of what is far and near;

You come from the impermanent world of phenomena.

But I love you as a transcendent being![44]

Among the Perfected who transmitted poetry to Yang Xi, the most prolific (9 poems from 21 August 365 to 28 May 366) was Lady Youying (右英婦人), the thirteenth daughter of the goddess Queen Mother of the West. All nine were "seduction songs" for Yang's patron Xu Mi, who the Perfected said was destined to join Lady Youying in spirit marriage and ascend to Shangqing heaven. At that time Xu Mi was in his early sixties, and seen by the Perfected to be entangled in earthly, carnal desires. Lady Youying hoped that her poetry, filled with the colors, sounds, and scenes of the celestial regions, will convince him to join her in a mystical sacred marriage in the "unseen realm".[45] However, despite Lady Youying's repeated otherworldly pleadings, Xu Mi waited over a decade to join her. He completed his official career in the capital, and moved to Maoshan where he practiced Shangqing worship until his death in 376.[46]

Yang recorded that Lady Youying dictated the following poem on 6 March 366.

Reining in the sky-lights, I ascend the empyrean's dawn-source,

Rambling to revelry in the Palace of Watchet Whitecap.

Prismatic clouds wreathe the cinnabar auroras;

Numinous cumuli bestrew the Eight Hollows.

The Perfected Ones on high chant in rose-gem abodes;

Lofty Transcendents carol in blue-gem chambers.

Nine phoenixes sing through the vermilion sounding-pipes;

The rhythms of the void commingle in the plumed bells.

With our necks entwined, within the Golden Court

I'll unite with my mate amidst the unseen realm.

Together we will tap the ichor of the jade ale—

In a flash and a flicker, are now in the nonage of infancy!

—Well then, why do you crouch athwart the worldly road,

Your lapses and maladies increasing with every day?[47]

Songs such as Lady Youying's are "direct heirs" to the Chuci's Yuan you Far-off Journey, which poetically describes a shamanic/Daoist flight around the heavens and earth.[48]

Buddhist influences

The Silk Road transmission of Buddhism into China began in the 1st or 2nd century CE, and the new foreign religion had become widely popular by the time the Zhengao was written. The Daoist Lingbao School, which began in the early 5th century, borrowed many practices and terms from Buddhism.[49] The Shangqing Daoist Zhengao incorporated some passages from Buddhist texts and adapted religious concepts such as monastic celibacy.

Some revelations the Perfected bestowed upon Yang were corrections of existing texts in other traditions. One of the clearest examples of Buddhist borrowings in the Zhengao is a portion of the Sishi'erzhang jing Sutra of Forty-two Chapters, which is believed to have been the first Buddhist scripture translated into Chinese.[50] The Chinese philosopher and author Hu Shih (1935) first discovered the Sishi'er zhang jing borrowings in the Zhengao (volumes 6 and 9, and criticized Tao Hongjing for plagiarism.[51]

The Zhengao imbeds borrowed passages within discourses attributed to Daoist deities. The following passage uses two fundamental tenets of Buddhism—Dukkha "suffering; unsatisfactoriness" (Chinese kǔ 苦 "bitterness"), the first of the Four Noble Truths, and Saṃsāra "karmic cycle; reincarnation" (lúnhuí 輪回 "transmigration")— to exhort Shangqing adepts toward single-minded, painstaking training and to reject the futile cravings of mundane life.

The Blue Boy of Fangzhu appeared and proclaimed, "For a person to practice the Tao is also to suffer, but to not practice the Tao is also to suffer. People from their birth reach old age, and from old age reach [the stage of] illness. Protecting their bodies they reach [the point of] death. Their suffering is limitless. In their minds they worry and they accumulate transgressions. With their births and deaths unending, their suffering is difficult to [accurately and sufficiently] describe (emphasis added). Even more so it is because many do not live to their old age ordained by Heaven! [By saying that] to practice the Tao is also to suffer, I mean that to maintain the Perfect purely and immaculately, to guard the mysterious and long for the miraculous, to search for a teacher while struggling, to undergo hundreds of trials, to keep your heart diligent without failure, to exert your determination firmly and clearly; these are also the utmost in suffering."[52]

Another recurring Sutra of Forty-two Chapters theme in the Zhengao is the elimination of sexual desire. One borrowed passage states, "As for what is great among longings and desires, nothing is greater than lust. The guilt it brings on has no limit, and it is a matter that cannot be forgiven." (Zhengao 6, Sishi'erzhang jing 22).[53] Prior to significant Buddhist influence, Daoists traditionally encouraged the practice of "retention of the semen" as a means to increase longevity, with jīng (精) meaning both physical "sperm" and spiritual "essence" in Neidan Internal Alchemy and Traditional Chinese medicine. Thus, "The Oral Lesson of the Female Immortal, the wife of Liu Gang" warns, "Those who seek immortality must not associate with women." (Zhengao 10).[54]

The Zhengao used yàolì (藥力, "efficacy of a medicine") in an unclear meaning: "If a Taoist adept seeks to become an immortal, he must not copulate with women. Each time you copulate, you nullify a full year's medicinal strength. If you ingest nothing and engage in bedroom activities, you will lose thirty years off your life span." (10)[55] interpreting that uncelibate adepts could take special medicines to supplement their jing).

One of the primary Zhengao reasons for maintaining celibacy and eliminating lust was to attain direct spiritual encounters with immortals and gods. "Those who are perfect have no feelings of [erotic] passion and desire, nor any thoughts of man and woman. If [thoughts of] red and white exist in one's bosom, the sympathy of Perfected beings will not come about as a response, and Divine Women and Superior Worthies will not descend [before you]." (6).[56] This "red and white" may refer to blood and sperm.[57] The Zhengao poem "Spiritual Union, Not Sexual Intercourse" begins, "The world prizes sweetly scented intercourse / The way prescribes union in the mystic empyrean"[58]

Literary value

The Zhengao was influential in medieval Chinese literature and continues to have extraordinary lyrical value. The works of many of China's greatest poets, including Li Bo, Wang Wei, Bo Juyi, and Li Shangyin, were influenced by it.[2]

The first readers of the Zhengao were Eastern Jin dynasty literari, well-educated intellectuals who esteemed poetic ability. The text comprises some 70 poems and songs recited to Yang Xi by the Shangqing divinities, and they communicated with verbal artistry specifically "calculated to impress and enchant" the literate aristocracy of the Eastern Jin court. Yang Xi's "virtuoso efforts combining spiritual content with lyric technique" precisely appealed to this 4th-5th century Chinese audience, since most of the Perfected Ones' verses had the then current pentasyllabic meter favored by the Eastern Jin literati themselves.[59]

For a final example of Yang Xi's literary ability, consider this description of when Lady of Purple Tenuity first appeared to him (described above). "Her garments flashed with light, illumining the room. Looking at her was like trying to discern the shape of a flake of mica as it reflects the sun. Her billowing hair, black and long at the temples, was arranged exquisitely. It was done up in a topknot on the crown of her head, so that the remaining strands fell almost to her waist. There were golden rings on her fingers and jade circlets on her arms. judging by her appearance, she must have been about thirteen or fourteen."[60]

References

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R. (1996). "Declarations of the Perfected". In Lopez, Donald S. (ed.). Religions of China in Practice. Princeton University Press. pp. 166–179. ISBN 9780691021430.

- Eskildsen, Stephen (1998). Asceticism in Early Taoist Religion. SUNY Press.

- Lopez, Donald S., ed. (1996). "Seduction Songs of One of the Perfected". Religions of China in Practice. Translated by Kroll, Paul W. Princeton University Press. pp. 180–187. ISBN 9780691021430.

- Kroll, Paul W. (2017). A Student's Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese (rev. ed.). E.J. Brill. ISBN 9789004325135.

- Ledderose, Lothar (1984). "Some Taoist Elements in the Calligraphy of the Six Dynasties". T'oung Pao. 70 (4/5): 246–278. doi:10.1163/156853284X00107. JSTOR 4528317.

- Robinet, Isabelle (1984). La révélation du Shangqing dans l'histoire du taoïsme. École française d'Extrême-Orient. ISBN 9782855397375.

- Robinet, Isabelle (2008b). "Zhengao 真誥 Declarations of the Perfected; Authentic Declarations". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Taoism. Vol. II. Routledge. pp. 1248–1250. ISBN 9780700712007.

- William Theodore de Bary; Irene Bloom, eds. (1999). "Pronouncements of the Perfected". Sources of Chinese Traditionand. Translated by Schipper, Kristofer. Columbia University Press. pp. 402–404.

- Smith, Thomas E. Smith (2013). Declarations of the Perfected: Part One: Setting Scripts and Images into Motion. Three Pines Press. ISBN 9781387209231.

- Strickmann, Michel (1977). "The Mao shan Revelations: Taoism and the Aristocracy". T'oung Pao. Second series. 63 (1): 1–64. doi:10.1163/156853277X00015. JSTOR 4528095.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Robinet 2008b, p. 1248.

- 1 2 3 Schipper 1999, p. 403.

- ↑ Espessett, Grégoire (2008). "Yang Xi 楊羲". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Taoism. Vol. II. Routledge. p. 1147 (1147-1148).

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 16.

- ↑ Bokenkamp 1996, p. 167.

- ↑ Tr. Ledderose 1984, pp. 254, 256.

- ↑ Smith 2013, p. 16.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 41.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, pp. 3, 42.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 32.

- ↑ Kohn 2008b: 119.

- 1 2 3 Robinet 2008b, p. 1249.

- ↑ Robinet 2008b, pp. 1248, 206.

- 1 2 Bokenkamp 1996.

- ↑ Kroll 1996.

- 1 2 Schipper 1999.

- ↑ Komjathy, Louis (2004), "Daoist Texts in Translation", Center for Daoist Studies, 42-43.

- 1 2 3 Smith 2013.

- ↑ Mugitani Kunio (1991), Shinkō sakuin 「真誥」索引 [Concordance to the Zhengao], Kyōto daigaku Jinbun kagaku kenkyūjo.

- ↑ Yoshikawa Tadao 吉川忠夫 and Mugitani Kunio 麥谷邦夫, trs. (2000), Shinkō kenkyū: yakuchū hen 「真誥」研究 譯注篇 [Studies on the Zhengao: Japanese annotated translation]. Kyōto daigaku Jinbun kagaku kenkyūjo.

- ↑ Pregadio, Fabrizio (2008). "Reference Works for Taoist Studies". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Taoism. Vol. II. Routledge. pp. 1311–1331.

- ↑ Schipper 1999, p. 402.

- ↑ Kroll 2017.

- ↑ Kroll 2017, pp. 598–9.

- ↑ Miura, Kunio (2008). "'Zhenren 真人 Real Man or Woman; Authentic Man or Woman; True Man or Woman; Perfected". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Taoism. Vol. II. Routledge. p. 1265 (1265-1266).

- ↑ Kroll 2017, p. 130.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1956). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 2, History of Scientific Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521058001.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph; Lu, Gwei-djen (1974). Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology. Part 2, Spagyrical Discovery and Inventions: Magisteries of Gold and Immortality. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1086/ahr/82.4.1041. ISBN 0-521-08571-3.

- ↑ Eskildsen 1998.

- ↑ Robinet, Isabelle (2008). "Dengzhen yinjue 登真隱訣, Concealed Instructions for the Ascent to Reality (or: to Perfection)". In Fabrizio Pregadio (ed.). The Routledge Encyclopedia of Taoism. Vol. I. Routledge. pp. 356–357. ISBN 9780700712007.

- ↑ Robinet 2008b.

- 1 2 Theobald, Ulrich (2011), Zhengao 真誥 "The Proclamation of the Perfect", Chinaknowledge.

- ↑ Eskildsen 1998, p. 72.

- 1 2 Robinet, Isabelle (2000), "Shangqing—Highest Clarity", in Daoism Handbook, ed. by Livia Kohn, 196-224, Brill. p. 206.

- ↑ Robinet 2008b, p. 1250.

- ↑ Robinet 1984, 2: 359-62.

- ↑ Robinet 1984, 2: 389-98.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 4.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 5.

- ↑ Robinet, Isabelle (1993), Taoist Meditation, The Mao-shan Tradition of Great Purity, tr. by Julian F. Pas and Norman J. Girardot, State University of New York. p. 228.

- ↑ Bokenkamp 1996, pp. 168–9.

- ↑ Bokenkamp 1996, p. 170.

- ↑ Tr. Bokenkamp 1996, pp. 175-6.

- ↑ Tr. Schipper 1999, p. 403, cf. Smith 2013, p. 162.

- ↑ Kroll 1996, p. 181.

- ↑ Ledderose 1984, p. 255.

- ↑ Kroll 1996, p. 186.

- ↑ Kroll 1996, p. 181.

- ↑ Zürcher, Erik (1980), "Buddhist Influence on Early Taoism," T'oung Pao 66, 84-147.

- ↑ Strickmann 1977, p. 10.

- ↑ Eskildsen 1998, p. 183.

- ↑ Vol. 6, tr. Eskildsen 1998, p. 73; italicized portions from Sishi'erzhang jing 35.

- ↑ Tr. Eskildsen 1998, p. 74.

- ↑ Tr. Eskildsen 1998, p. 76.

- ↑ Tr. Eskildsen 1998, p. 75.

- ↑ Tr. Eskildsen 1998, p. 78.

- ↑ Eskildsen 1998, p. 184.

- ↑ Tr. Smith 2013, p. 137.

- ↑ Kroll 1996, p. 180.

- ↑ Tr. Bokenkamp 1996, p. 171.

External links

- Declarations of the Perfected, FYSK Daoist Culture Centre Database.

- 真誥, Zhengao versions at Chinese Text Project.