婴儿潮世代

婴儿潮世代(英語:,常简称为)是沉默世代之后、X世代之前的一代人口群体,通常指1946年至1964年之间出生的一代人,当时正值20世纪中期的婴儿潮时期。[1]不同国家这一代人的具体时间、人口背景和文化特征可能有所不同。[2][3][4][5]婴儿潮在西方常被形容为“冲击波”()[6]和“蟒蛇腹中的猪”()。[7][8]多数婴儿潮一代的父母属于最伟大的一代或沉默一代,他们的子女则通常是X世代或Y世代。[9]

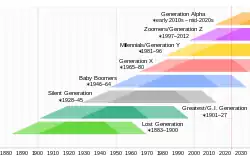

| 西方世界的主要世代 |

|---|

|

在西方,婴儿潮一代的童年处于1950年代和1960年代。他们当时经历了重大的教育改革,这既是冷战时期意识形态对峙的一部分[10][11],也是两次世界大战战间期的延续。[12][13]到1960年代和1970年代,随着数量相对较多的这代年轻人步入青少年时期(最年长的婴儿潮一代于1964年年满18岁),他们及其周围的人创造了这一代人特有的话语体系[14],同时以其庞大的人数推动了1960年代反文化运动等社会运动。[15][16]

在许多国家,这一时期由于战后年轻人数量激增而导致政治非常不稳定。[16][17]例如在中国,婴儿潮一代经历了文化大革命,并在成年后受到一孩政策的影响。[18]这些社会文化的改变对婴儿潮一代的认知产生了重要影响,同时也造成人们越来越普遍地倾向于以世代来定义世界。这种对世代的划分是一个相对较新的现象。此外,这一代人也比前几代人更早进入青春期。[19]

在欧洲和北美,许多婴儿潮一代是在社会财富日益增长、战后政府对住房和教育进行广泛补贴的时代长大的。[6]他们在成长过程中真诚地相信世界会随着时间的推移而变得更加美好。[7]那些生活水平和受教育程度较高的人往往对改善条件有着更高的要求。[16][20]到21世纪初期,由于生育率低于世代更替水平和人口老龄化,一些发达国家的婴儿潮一代成为了其社会中最大的人口群体。[21]在美国,他们是仅次于Y世代的第二大年龄群体。 [22]

参考文献

- Sheehan, Paul. . The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 September 2011 [21 May 2019]. (原始内容存档于21 May 2019).

- Owram, Doug. . Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1997-12-31. ISBN 978-1-4426-5710-6. doi:10.3138/9781442657106.

- Little, Bruce; Foot, David K.; Stoffman, Daniel. . Foreign Policy. 1998, (113): 110. ISSN 0015-7228. JSTOR 1149238. doi:10.2307/1149238.

- Salt, Bernard. . South Yarra, Victoria: Hardie Grant Books. 2004. ISBN 978-1-74066-188-1.

- Delaunay, Michèle [VNV]. . Paris. 2019. ISBN 978-2-259-28062-4. OCLC 1134671847.

- Owram, Doug. . Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1997: x. ISBN 978-0-8020-8086-8.

- Jones, Landon. . New York: Coward, McCann and Geoghegan. 1980.

- Krugman, Paul. . The New York Times. 21 June 2000 [24 April 2021]. (原始内容存档于April 24, 2021).

- Rebecca Leung. . CBS News. 4 September 2005 [24 August 2010]. (原始内容存档于November 4, 2013).

- Stroke, H. Henry. . Physics Today. August 1, 2013, 66 (8): 48 [October 11, 2020]. Bibcode:2013PhT....66R..48S. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2085. (原始内容存档于October 24, 2022).

- Knudson, Kevin. . The Conversation. 2015 [September 9, 2015]. (原始内容存档于September 15, 2015).

- Garraty, John A. . United States of America: Harper Collins. 1991: 896–7. ISBN 978-0-06-042312-4.

- Gispert, Hélène. . CultureMATH. [November 4, 2020]. (原始内容存档于July 15, 2017) (法语).

- Pinker, Steven. . Penguin. 2011: 109. ISBN 978-0-141-03464-5.

- Owram, Doug. . Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 1997: xi. ISBN 978-0-8020-8086-8.

- Suri, Jeremi. . American Historical Review. February 2009, 114 (1): 45–68. JSTOR 30223643. doi:10.1086/ahr.114.1.45.

- Turchin, Peter. . Nature. February 3, 2010, 403 (7281): 608. Bibcode:2010Natur.463..608T. PMID 20130632. doi:10.1038/463608a

.

. - Woodruff, Judy; French, Howard. . PBS Newshour. August 1, 2016 [August 13, 2020]. (原始内容存档于September 26, 2020).

- Hobsbawn, Eric. . Abacus. 1996. ISBN 978-0-349-10671-7.

- Hobsbawn, Eric. . Abacus. 1996. ISBN 978-0-349-10671-7.

- Zeihan, Peter. . Austin, TX: Zeihan on Geopolitics. 2016. ISBN 978-0-9985052-0-6. Population pyramids of the developed world without the U.S. 的存檔,存档日期October 30, 2020,. and of the U.S. in 2030 的存檔,存档日期October 10, 2020,..

- Fry, Richard. . Pew Research Center. 28 April 2022 [31 May 2022]. (原始内容存档于April 28, 2020).