The history of Anglicanism in Sichuan (or "Western China")[note 1] began in 1887 when Anglican missionaries working with the China Inland Mission began to arrive from the United Kingdom. These were later joined by missionaries from the Church Missionary Society and Bible Churchmen's Missionary Society. Or according to Annals of Religion in Mianyang, in 1885, a small mission church was already founded in Mianyang by Alfred Arthur Phillips and Gertrude Emma Wells of the Church Missionary Society.[1] Missionaries built churches, founded schools, and distributed Chinese translations of Anglican religious texts. These efforts were relatively successful and Anglicanism grew to become one of the two largest denominations of Protestant Christianity in the province, alongside Methodism.[2]

Nonetheless, missionary activity in China generated controversy among many native Chinese and faced armed opposition during both the Boxer Rebellion and the later Chinese Communist Revolution. Although the former did not affect Sichuan so much as some other parts of China, the province was one of the hotbeds of anti-missionary riots throughout its ecclesiastical history.[3]

Numerous mission properties and native church leaders in Sichuan were respectively destroyed and killed by communists in the mid-1930s.[4] After the communist take over of China in 1949, missionaries were expelled and activity ceased. Under government oppression in the 1950s, Anglicans and other Protestants across China severed their ties with overseas churches and their congregations merged into the Three-Self Patriotic Church. Since 1980, services for Chinese Protestant churches have been provided by the China Christian Council.

History

First Anglican missionaries

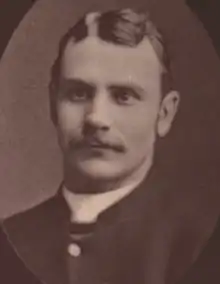

The Cambridge Seven were Anglicans serving under the interdenominational society China Inland Mission (CIM). Four of them were going to be the first Anglican missionaries working in the western province of Sichuan. William Cassels, was already an ordained priest; Arthur T. Polhill-Turner, was studying for holy orders when he volunteered for the mission in China; Montagu Proctor-Beauchamp, a baronet from the Proctor-Beauchamp family; and Arthur's elder brother Cecil H. Polhill-Turner, a Pentecostal revivalist. They left London for China on 5 February 1885. After studying the local language, the four were transferred to Sichuan in 1887. Cassels held the licence of George Moule, Bishop of Mid-China, as the Western China district fell within the Mid-China jurisdiction by the time. Arthur was before long ordained both deacon and priest by the same Bishop.[5][6] Cecil was first based at the capital Chengdu (Chengtu) and the eastern Sichuanese city Chongqing (Chungking), but he felt drawn towards the people of Tibet. After helping with mission work in Kalimpong in India in 1896, he moved to Dajianlu (Tatsienlu), a Khams Tibetan city of western Sichuan. From there he had laboured on the Sino- and Indo-Tibetan borders since then.[7][8]

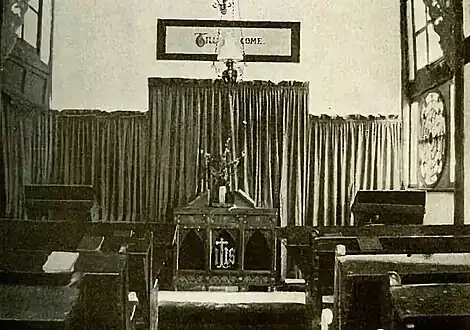

In 1893, Trinity Church was built in Baoning (Paoning) under Cassels's supervision.[9] As the first Anglican church in Sichuan, the chosen style was in consideration of being more acceptable to the locals. It adopted the style of traditional residential buildings in northern Sichuan, fully blended into the surroundings. The British explorer Isabella Bird described in her book The Yangtze Valley and Beyond, that the church "is Chinese in style, the chancel windows are 'glazed' with coloured paper to simulate stained glass, and it is seated for two hundred. [...] The church was crammed at matins, and crowds stood outside, where they could both see and hear, this publicity contrasting with the Roman practice."[10]

.png.webp)

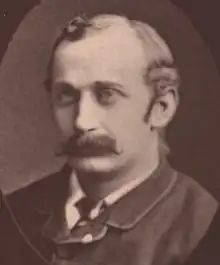

At the close of 1891, the Rev. James Heywood Horsburgh of Church Missionary Society (CMS, belonging to the Church of England), along with his wife Mrs Horsburgh, the Rev. O. M. Jackson, three laymen, and six single women missionaries, entered Sichuan as the first band of CMS missionaries to take up work in that province. By an amicable arrangement with the CIM, the northern part of the province was divided into two districts. The district lies mainly to the north of the capital Chengdu was occupied by the CMS, while the CIM's Church of England district was to the east of that of the CMS.[11]

When Horsburgh's party first arrived, they were unable to secure or rent any houses in the principal towns of what was to be the occupied area of their future mission; and they dwelt at first with their fellow-workers of the CIM. It did not take them long, however, to begin itinerant work, staying for days or weeks at local inns, such brief stays not at all fruitless. Among the leaders of this group was an exceptionally gifted woman, Alice Entwistle, who was largely responsible for the opening of the important town of Mianzhou (Miencheo).[11][12]

By 1894, CMS work had started in Mianzhou (Mienchow), Jiangyou (Chungpa), An County (Anhsien), Mianzhu (Mienchu) and Xindu (Sintu); the first CMS church was founded in Jiangyou in 1894.[13] By 1908, CMS alone claimed eight stations in an area of approximately one hundred and fifty square miles, all of which were in the northwest of the province. Meanwhile, the CIM workers, based in Baoning, were also breaking ground in northeast Sichuan.[14] Arthur Polhill spent ten years (1888–1898) in Bazhou doing evangelism. In 1899 he moved to Dazhou (Suiting), where he built a large multi-purpose Gospel Hall in 1904. A number of outstations were established following the building's completion.[15]

At that time, Sichuan was the landlocked, westernmost province of China, bordering Tibet. It was quite isolated, compared with those coastal provinces in east China. The missionaries scattered, and the persistent state of turmoil of the countryside with war, banditry and general unrest made the work difficult and dangerous.[16]

Prior to 1895, CMS mission in Sichuan had been under the direction of George Moule, the Bishop of Mid-China, but it was quite impossible for him to give adequate supervision to a region nearly 2,000 miles away from his headquarters, and it was therefore decided to create a new Diocese of Western China (a.k.a. Diocese of Szechwan). With the approval of the Archbishop of Canterbury (Edward White Benson) and the CMS, Cassels was consecrated bishop on St. Luke's Day, 18 October 1895, at Westminster Abbey.[12][17]

That same year was marked by a serious outbreak of anti-foreign agitation which spread throughout the province. In the capital Chengdu, the property of three Protestant missions and that of the Roman Catholics was destroyed, and in other towns the work of the CMS stations was temporarily disrupted. The missionaries, however, were able to remain at their posts, and despite opposition and occasional waves of intense anti-foreign sentiment, the work continued to go forward until the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. This unrest did not affect Sichuan so much as some other parts of China, nevertheless missionaries were obliged by consular orders to retire to the coast. During their absence, the local converts defended their faith and carried on all the regular services.[12]

20th century

.jpg.webp)

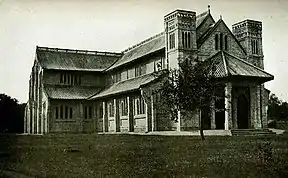

Following the establishment of the Diocese of Western China and the increasing number of converts, the Trinity Church had become too small. Construction of a neo-Gothic pro-cathedral began in 1913 under the supervision of the Australian architect George A. Rogers.[18] Upon the completion of the construction, Cassels invited the Bishop of Hankow, Logan H. Roots, to come and preach a series of sermons in connection with the opening of the pro-cathedral.[19] This caused some dissension among the foreign staff. As staunch evangelicals, they were upset by the idea of something to be called a cathedral. Two of the women missionaries were particularly upset by the presence of two bishops in their convocation robes, standing posture at the offertory, and flowers in two handsome vases placed within the chancel rails. They found vent in other spheres of work.[9] In addition, the diocese founded its official newsletter, The Bulletin of the Diocese of Western China, in 1904. It was renamed several times during its 54-year run, with the last print published in 1958.[20]

The growing maturity of the Sichuanese Church was seen in Cassels's appointment of Ku Ho-lin as archdeacon in 1918. Ku was remarkable as a convert from Islam,[21] and had been one of those who held the Church together when foreign staff had to leave during the Boxer Rebellion. Overseeing the greatly increased number of congregations was becoming too much for Cassels alone.[22] As early as 1915, he raised with the Archbishop of Canterbury (Randall Davidson) the question of the division of the diocese. It did not seem advisable at the time, but relief was given by the appointments of an archdeacon and of Howard Mowll as assistant bishop in 1922, who was particularly in charge of the CMS district.[23] Cassels welcomed the Bible Churchmen's Missionary Society (BCMS, seceded from the CMS in 1922) field workers when they approached him, as he had welcomed Rev. Horsburgh and his party many years before. He wrote: "With regard to the BCMS coming into the diocese, I must say I am most thankful to think that there is some prospect of them taking up the work in the Kwangan, Yochih and Linshui region, which is now left without any oversight."[24]

In 1921, members of fanatical bands self-denominated "Divine Soldiers", killed six or seven Christians in Wan County, eastern Sichuan. The province was also affected by the widespread Anti-Christian Movement in the 1920s, which had its origins in the east and north parts of China, such as Shanghai and Beijing.[25]

Bishop Cassels died on 7 November 1925. He had served forty years in Sichuan, based at Langzhong (Baoning), thirty of these years as bishop, and was succeeded by Howard Mowll. It was largely the result of Cassels's work that Christianity in its Anglican form had become well established in eastern Sichuan. In 1885, there was no Christian congregation apart from Roman Catholics.[25] In a letter written nearly forty years after his arrival in Sichuan, Cassels gave a brief account of the mission's achievements:[26]

Mrs. Chao, the Bible-woman at Xindianzi (Sin-tien-tsï), near Baoning, a small mission station that had opened in 1892; before 1901.When I came here nearly forty years ago, there was no Mission House or Church. Now there are twenty-five central stations and one hundred and twenty outstations, and some forty or fifty Churches have been built. Then there were no Christians nor even a catechumen of any kind. Now over 10,000 converts have been baptized, and of these 6700 odd have been confirmed; and the returns show that there are nearly 2500 baptized persons who have not yet been confirmed, as well as over 2000 catechumens, a proportion of whom will, it is hoped, be baptized before long. And as to Chinese workers, it is hardly necessary to say that there were none of any kind at all in those days. But now twelve tried men have been admitted to Holy Orders, of whom one has passed away and one has been made Archdeacon. There are also in the diocese ninety-eight licensed preachers, not including colporteurs, Bible-women and others.

I must not stay to allude in detail to the Schools for boys and girls, the Hospitals, the Hostel at Chengtu, the Training College (an institution of the greatest value), nor to the Cathedral, which have all come into being since the formation of the diocese.

For what has been done I give most humble and hearty thanks to God on high.

And it is the devoted band of my dear fellow-labourers, both missionary and Chinese, that God has used as His instruments during these forty years, and particularly during the thirty years since the formation of the diocese.

But whilst praising God for what He has done, we need to remind ourselves and you that this is but a drop in the bucket to the work which lies before us.

The mission work mostly concentrated on evangelisation in villages and towns, instead of big institutions and schools. There was, however, a Church hospital at Langzhong. For a time there was also a girls' school, a small theological college and a preacher's training school. The Langzhong Hospital was for a long time the only hospital in northeast Sichuan. Hospitals were also maintained at Dazhou and Liangshan. In Eastern Sichuan district, the aid came from the CIM and later from the BCMS; in Western Sichuan district the CMS. Anglicanism was much less widespread in the latter district than in the former, although it did extend to Songpan and Mao County, practically in the Qiang and Tibetan region. A Church hospital was built at Mianzhu, western Sichuan, where Dr. John Howard Lechler had worked for thirty years since 1908.[25] For a time, Montagu Robert Lawrence, T. E. Lawrence's elder brother, worked there as a locum during Lechler's absence.[27]

In 1918, the CMS became a partner in the West China Union University created by four Protestant mission societies in 1910 in the capital.[28] The Anglicans provided at different times several members of staff for the university, including Dr. H. G. Anderson, who was working at its College of Medicine and Dentistry. They also provided a hostel for students there.[29] In 1923, during the Anti-Christian Movement, two English clergymen, F. J. Watt and R. A. Whiteside, were shot to death by brigands among the mountains between Mianzhu and Mao County.[30] One of them was a teacher of a boys' boarding school at Mianzhou.[25] A memorial stele was erected at the foot of the mountain where the two men were murdered.[31]

In 1929, Bishop Mowll appointed two assistant bishops for the West China Diocese. Ku Ho-lin (a.k.a. Ku Shou-tsi) was entrusted with the northeast Sichuan district, which owed its origin to the Anglican section of the CIM; and Song Cheng-tsi with the west Sichuan district where the Church's connection was with the CMS. Ku's consecration took place on 16 June at the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist in Langzhong. Brook Hannah, the assistant superintendent, served as litany reader during the ceremony. Song's consecration took place on 29 June at St. Thomas' Church in Mianzhu.[32]

That same year (1929), an evangelical Anglican missionary, Vyvyan Donnithorne, was sent to Hanzhou by the CMS. He served as pastor at the local Gospel Church until 1949, before being transferred to the Canary Islands, Spain.[33] During his stay in Hanzhou, he was appointed a member of the West China Border Research Society and a key figure in the discovery of the archaeological site now known as Sanxingdui.[34]

.pdf.jpg.webp)

A Chinese translation of the Book of Common Prayer was published in 1932, revised and authorized for use in the Diocese of Szechwan.[35] In 1933, Bishop Mowll left to take up his new post as Archbishop of Sydney and John Holden was transferred from the Diocese of Kwangsi-Hunan to succeed him.[36]

The middle 1930s was an extremely difficult period for the Church in Sichuan. The communist armies retreated through Sichuan to Shaanxi as they were driven out of Jiangxi by the Nationalist armies, later known as the Long March. Church workers had no choice but to temporarily leave their mission centres due to widespread lawlessness and banditry along the armies' retreat routes.[37] Churches, chapels, schools, pastor's homes at Lifan, Zagunao (Tzagulao), and the church property of the CMS at Mao County (Maochow) were entirely destroyed by communist troops.[38] During this period, Bishop Holden made considerable advances in transferring authority and responsibility to the locals that were still almost held exclusively by the CMS mission conference by the 1930s.[37]

In 1936, the Diocese of Western China was split into Diocese of East Szechwan and Diocese of West Szechwan.[39] Holden continued as bishop of the new Diocese of West Szechwan until being forced to return to England because of ill-health the following year. He was succeeded by Song Cheng-tsi. Frank Houghton was consecrated as first bishop of the new Diocese of East Szechwan. Ku Ho-lin continued as assistant bishop of East Szechwan until he retired in 1947. Kenneth Bevan became bishop of East Szechwan after Houghton's resignation in 1940. During this period, in addition to hospitals in Langzhong (Langchung) and Liangshan, the Church also had middle schools in Dachuan and Liangshan. Two celebrations were held in 1945, one for the Golden Jubilee of the Diocese of Szechwan, the other for the Diamond Jubilee of the start of the Anglican mission in Sichuan.[29]

After 1949

After the communist takeover of China in 1949, Protestant churches in China were forced to sever their ties with respective overseas churches, which led to the merging of all the denominations into the communist-sanctioned Three-Self Patriotic Church.[40]

The Anglican Church in China was never formally dissolved, but all activities had ceased by 1958.[41] The China Christian Council was founded at the third national Christian conference in 1980 to unite and provide services for Protestant churches, formulating Church Order and encouraging theological education.[42] In 2018, the detention of 100 Christians in Sichuan, including their pastor Wang Yi, raised concerns about religious crackdown in China.[43]

Gallery

Map of Sichuan showing Anglican mission stations of China Inland Mission (CIM), Church Missionary Society (CMS) and Bible Churchmen's Missionary Society (BCMS), in the West China Diocese, 1926.

Map of Sichuan showing Anglican mission stations of China Inland Mission (CIM), Church Missionary Society (CMS) and Bible Churchmen's Missionary Society (BCMS), in the West China Diocese, 1926..svg.png.webp) Map of Sichuan showing Anglican mission stations of CIM, CMS and BCMS, in the West China Diocese (pinyinified version)

Map of Sichuan showing Anglican mission stations of CIM, CMS and BCMS, in the West China Diocese (pinyinified version)

Gospel Church, Mianzhou (CMS; West Szechwan Diocese)

Gospel Church, Mianzhou (CMS; West Szechwan Diocese) St John's Church, Chengdu (CIM; West Szechwan Diocese)

St John's Church, Chengdu (CIM; West Szechwan Diocese) Interior of the Trinity Church at Baoning, 1890s (CIM; East Szechwan Diocese)

Interior of the Trinity Church at Baoning, 1890s (CIM; East Szechwan Diocese) Interior of St. John's Cathedral at Baoning, 1910s (CIM; East Szechwan Diocese)

Interior of St. John's Cathedral at Baoning, 1910s (CIM; East Szechwan Diocese)

See also

- Anglicanism in Mianyang

- Christianity in Sichuan

- The West China Missionary News

- Anti-Christian Movement (China)

- Anti-missionary riots in China

- Antireligious campaigns of the Chinese Communist Party

- Church Missionary Society in China

- Denunciation Movement

- House church (China)

- Category:Diocese of Szechwan

- Category:Anglican missionaries in Sichuan

Notes

- ↑ Sichuan, formerly romanized as Szechwan, Szechuan, or Ssuchʻuan; also referred to as "West China" or "Western China".

References

- ↑ Mianyang Bureau of Religious Affairs, ed. (1998). "礼拜堂选介——涪城礼拜堂" [Introduction of Selected Church Buildings: Fucheng Church]. 绵阳市民族宗教志 [Annals of Religion in Mianyang] (in Simplified Chinese). Chengdu: Sichuan People's Publishing House. pp. 432–433. ISBN 722003993X.

- ↑ Stauffer 1922, p. 228.

- ↑ Lü, Shih-chiang (1976). "晚淸時期基督敎在四川省的傳敎活動及川人的反應(1860–1911)" [The Evangelization of Sichuan Province in the Late Qing Period and the Responses of the Sichuanese People (1860–1911)]. History Journal of the National Taiwan Normal University (in Traditional Chinese). Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University Department of History: 282. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

- ↑ Plewman 1936, pp. 11–18.

- ↑ Norris 1908, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Gray 1996, p. 13.

- ↑ Usher, John M. (ed.). "About Cecil Polhill". pconline.org.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ↑ "Papers of Cecil and Arthur Polhill". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- 1 2 Gray 1996, p. 34.

- ↑ Bird-Bishop, Isabella (1900). The Yangtze Valley and Beyond (volume II). London: John Murray. pp. 6–8.

- 1 2 Norris 1908, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 Stewart 1934.

- ↑ China Continuation Committee, ed. (1915). 中華基督教會年鑑 [The China Church Year Book] (in Traditional Chinese). Shanghai: The Commercial Press. p. 114.

- ↑ Norris 1908, p. 136.

- ↑ Usher, John M. (2019). "Beyond the Cambridge Seven: The Rev. Arthur Twistleton Polhill and the Dazhou Fú Yīn Táng". omf.org. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ Keen, Rosemary. "Church Missionary Society Archive—Section I: East Asia Missions: Western China". ampltd.co.uk. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ Stock, Eugene (1899). The History of the Church Missionary Society, Volume III. London: Church Missionary Society. p. 579.

- ↑ Broomhall 1926, p. 283.

- ↑ Broomhall 1926, p. 289.

- ↑ Tiedemann, R. G. (1 July 2016). Reference Guide to Christian Missionary Societies in China: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century. Milton Park: Routledge. ISBN 9781315497310.

- ↑ Norris 1908, p. 143.

- ↑ Broomhall 1926, p. 305.

- ↑ Gray 1996, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Broomhall 1926, pp. 329–330.

- 1 2 3 4 Gray 1996, p. 35.

- ↑ Broomhall 1926, pp. 356–357.

- ↑ Jones, Allan. "Robert Lawrence (1885—1971)". Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ "West China Union University" (PDF). divinity-adhoc.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- 1 2 Gray 1996, p. 68.

- ↑ Broomhall 1926, p. 326.

- ↑ Stewart, James Livingstone, ed. (May 1924). "A Suitable Stone" (PDF). The West China Missionary News. Chengdu: West China Missions Advisory Board. p. 2. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ↑ Kou, Yü-tien; Tsai, Fuh-tsu (10 September 1929). "四川祝聖古宋二牧爲會督之盛典" [Grand Ceremonies of the Episcopal Ordinations of the Archdeacon Ku Shou-tsi and the Deacon Song Cheng-tsi in the Diocese of Szechwan] (PDF). 聖公會報 [The Chinese Churchman] (in Traditional Chinese). 22 (17–18): 9. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ Ao, Tianzhao (2000). "三星堆古文化、古城、古国遗址发现始末" [The History of Discovery of the Ancient Sanxingdui Culture, and Ruins of Ancient Cities and Kingdoms of Shu]. 巴蜀史志 [Historical Records of Ba–Shu] (in Simplified Chinese) (4): 39. ISSN 1671-265X. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ Xu, Jay (2011). "Lithic Artifacts from Yueliangwan: Research Notes on an Early Discovery at the Sanxingdui Site". In Silbergeld, Jerome; Ching, Dora C. Y.; Smith, Judith G.; Merck, Alfreda (eds.). Bridges to Heaven: Essays on East Asian Art in Honor of Professor Wen C. Fong, Volume I. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15298-1.

- ↑ Cranmer, Thomas, ed. (1932). 公禱書 [Book of Common Prayer] (PDF) (in Traditional Chinese). Langchung: Diocese of Szechwan.

- ↑ Gray 1996, p. 67.

- 1 2 Gray 1996, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Plewman 1936, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Wickeri, Philip L., ed. (2015). Christian Encounters with Chinese Culture: Essays on Anglican and Episcopal History in China (PDF). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 211. ISBN 9789888208388. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ↑ Ferris, Helen (1956). The Christian Church in Communist China, to 1952. Montgomery, AL: Air Force Personnel and Training Research Center. p. 8. OCLC 5542137.

- ↑ Wickeri, Philip L. (2018). "The Vicissitudes of Anglicanism in China, 1912-Present". In Sachs, William L. (ed.). The Oxford History of Anglicanism, Volume V: Global Anglicanism, C. 1910–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-19-964301-1.

- ↑ Bays, Daniel H. (2012). A New History of Christianity in China. Chichester, West Sussex; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 189. ISBN 9781405159548.

- ↑ Berlinger, Joshua (17 December 2018). "Detention of 100 Christians raises concerns about religious crackdown in China". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 23 May 2023.

Bibliography

- Broomhall, Marshall (1926). W. W. Cassels: First Bishop in Western China. London: The China Inland Mission.

- Gray, G. F. S. (1996). Anglicans in China: A History of the Zhonghua Shenggong Hui (Chung Hua Sheng Kung Huei). New Haven, CT: The Episcopal China Mission History Project. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.4591.

- Norris, Frank L. (1908). "Chapter X. The Church in Western China". Handbooks of English Church Expansion: China. Oxford: A. R. Mowbray.

- Plewman, T. E. (January 1936). "The Red Terror in the Tribes Country". The West China Missionary News. Chengtu: West China Missions Advisory Board.

- Stauffer, Milton T., ed. (1922). The Christian Occupation of China. Shanghai: China Continuation Committee.

- Stewart, Emily Lily (1934). "Chapter II. The Way Reviewed". Forward in Western China. London: Church Missionary Society.