| Battle of Leyte Gulf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philippines campaign (1944–1945) of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

_burning_on_24_October_1944_(80-G-287970).jpg.webp) The light aircraft carrier Princeton on fire, east of Luzon, on 24 October 1944 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

The Battle of Leyte Gulf[5] (Japanese: レイテ沖海戦, romanized: Reite oki Kaisen, lit. 'Leyte Open Sea Naval Battle') was the largest naval battle of World War II and by some criteria the largest naval battle in history, with over 200,000 naval personnel involved.[6][7] It was fought in waters near the Philippine islands of Leyte, Samar, and Luzon from 23 to 26 October 1944 between combined American and Australian forces and the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), as part of the invasion of Leyte, which aimed to isolate Japan from the colonies that it had occupied in Southeast Asia, a vital source of industrial and oil supplies.

By the time of the battle, Japan had fewer capital ships (aircraft carriers and battleships) left than the Allied forces had total aircraft carriers in the Pacific, which underscored the disparity in force strength at that point in the war.[8] Regardless, the IJN mobilized nearly all of its remaining major naval vessels in an attempt to defeat the Allied invasion, but it was repulsed by the US Navy's Third and Seventh Fleets.

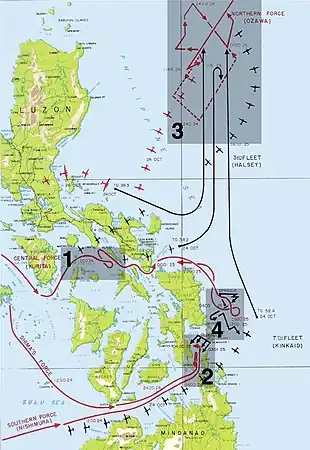

The battle consisted of four main separate engagements (the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, the Battle of Surigao Strait, the Battle off Cape Engaño, and the Battle off Samar), as well as lesser actions.[9] Allied forces announced the end of organized Japanese resistance on the island at the end of December.

It was the first battle in which Japanese aircraft carried out organized kamikaze attacks, and it was the last naval battle between battleships in history.[10][11] The Japanese Navy suffered heavy losses and never sailed in comparable force thereafter since it was stranded for lack of fuel in its bases for the rest of the war.[12][13]

Background

The Allied campaigns of August 1942 to early 1944 had driven Japanese forces from many of their island bases in the south and central Pacific Ocean, while isolating many of their other bases (most notably in the Solomon Islands, Bismarck Archipelago, Admiralty Islands, New Guinea, Marshall Islands, and Wake Island), and in June 1944, a series of American amphibious landings supported by Fifth Fleet's Fast Carrier Task Force captured most of the Mariana Islands (bypassing Rota). This offensive breached Japan's strategic inner defense ring and gave the Americans a base from which long-range Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers could attack the Japanese home islands.

The Japanese counterattacked in the Battle of the Philippine Sea. The U.S. Navy destroyed three Japanese aircraft carriers, damaged other ships, and shot down approximately 600 Japanese aircraft, leaving the Japanese Navy with very little carrier-borne air power and few experienced pilots.[14] However, the considerable land-based air power the Japanese had amassed in the Philippines was thought too dangerous to bypass by many high-ranking officers outside the Joint Chiefs of Staff, including Admiral Chester Nimitz.

Formosa vs. Philippines as invasion target

The next logical step was to cut Japan's supply lines to Southeast Asia, depriving them of fuel and other necessities of war, but there were two different plans for doing so. Admiral Ernest J. King, other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and Admiral Nimitz favored blockading Japanese forces in the Philippines and invading Formosa (Taiwan), while U.S. Army General Douglas MacArthur, wanting to fulfill the 1942 promise "I shall return", championed an invasion of the Philippines.

While Formosa could also serve as a base for an invasion of mainland China, which MacArthur felt was unnecessary, it was also estimated that it would require about 12 divisions from the Army and Marines. Meanwhile, the Australian Army, spread thin by engagements in the Solomon Islands, New Guinea, the Dutch East Indies and various other Pacific islands, would not have been able to spare any troops for such an operation. As a result, an invasion of Formosa, or any operation requiring much larger ground forces than were available in the Pacific in late 1944, would be delayed until the defeat of Germany freed the necessary manpower.[15]

Decision to invade the Philippines

A meeting between MacArthur, Nimitz, and President Roosevelt helped confirm the Philippines as a strategic target but did not reach a decision, and the debate continued for two months.[lower-alpha 1] Eventually Nimitz changed his mind and agreed to MacArthur's plan,[17] and it was eventually decided that MacArthur's forces would invade the island of Leyte in the central Philippines. Amphibious forces and close naval support would be provided by Seventh Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid.

Setup for the battle

The U.S. Seventh Fleet at this time contained units of the U.S. Navy and the Royal Australian Navy. Before the major naval actions in Leyte Gulf had begun, HMAS Australia and USS Honolulu were severely damaged by air attacks; during the battle proper these two cruisers were retiring, escorted by HMAS Warramunga, for repairs at the major Allied base at Manus Island, 1,700 mi (2,700 km) away.

Lack of unified command structures

U.S. Third Fleet, commanded by Admiral William F. Halsey Jr., with Task Force 38 (TF 38, the Fast Carrier Task Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher), as its main component, would provide more distant cover and support for the invasion. A fundamental defect in this plan was there would be no single American naval admiral in overall command. Kinkaid fell under MacArthur as Supreme Allied Commander Southwest Pacific, whereas Halsey's Third Fleet reported to Nimitz as C-in-C Pacific Ocean Areas. This lack of unity of command, along with failures in communication, was to produce a crisis and very nearly a strategic disaster for the American forces.[18][19] Coincidentally the Japanese plan, using three separate fleets, also lacked an overall commander.

Japanese plans

.jpg.webp)

The American options were apparent to the IJN. Combined Fleet Chief Soemu Toyoda prepared four "victory" plans: Shō-Gō 1 (捷1号作戦, Shō ichigō sakusen) was a major naval operation in the Philippines, while Shō-Gō 2, Shō-Gō 3 and Shō-Gō 4 were responses to attacks on Formosa, the Ryukyu Islands, and the Kurile Islands, respectively. The plans were for complex offensive operations committing nearly all available forces to a decisive battle, despite substantially depleting Japan's slender reserves of fuel oil.

On 12 October 1944, Halsey began a series of carrier raids against Formosa and the Ryukyu Islands with a view to ensuring that the aircraft based there could not intervene in the Leyte landings. The Japanese command, therefore, put Shō-Gō 2 into action, launching waves of air attacks against Third Fleet's carriers. In what Admiral Halsey refers to as a "knock-down, drag-out fight between carrier-based and land-based air",[20] the Japanese were routed, losing 600 aircraft in three days – almost their entire air strength in the region. Following the American invasion of the Philippines, the Japanese Navy made the transition to Shō-Gō 1.[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3]

Shō-Gō 1 called for Vice Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa's ships—known as the "Northern Force"—to lure the main American covering forces away from Leyte. Northern Force would be built around several aircraft carriers, but these would have very few aircraft or trained aircrew. The carriers would serve as the main bait. As the U.S. covering forces were lured away, two other surface forces would advance on Leyte from the west. The "Southern Force" under Vice Admirals Shoji Nishimura and Kiyohide Shima would strike at the landing area via the Surigao Strait. The "Center Force" under Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita—by far the most powerful of the attacking forces—would pass through the San Bernardino Strait into the Philippine Sea, turn southwards, and then also attack the landing area.[23][24]

Should we lose in the Philippines operations, even though the fleet should be left, the shipping lane to the south would be completely cut off so that the fleet, if it should come back to Japanese waters, could not obtain its fuel supply. If it should remain in southern waters, it could not receive supplies of ammunition and arms. There would be no sense in saving the fleet at the expense of the loss of the Philippines.

— Admiral Soemu Toyoda[25]

Submarine action in Palawan Passage (23 October 1944)

(Note: This action is referred to by Morison as 'The Fight in Palawan Passage',[26] and elsewhere, occasionally, as the 'Battle of Palawan Passage'.)

As it sortied from its base in Brunei, Kurita's powerful "Center Force" consisted of five battleships (Yamato, Musashi, Nagato, Kongō, and Haruna)[lower-alpha 4], ten heavy cruisers (Atago, Maya, Takao, Chōkai, Myōkō, Haguro, Kumano, Suzuya, Tone and Chikuma), two light cruisers (Noshiro and Yahagi) and 15 destroyers.[27]

Kurita's ships passed Palawan Island around midnight on 22–23 October. The American submarines Darter and Dace were positioned together on the surface close by. At 01:16 on 23 October, Darter's radar detected the Japanese formation in the Palawan Passage at a range of 30,000 yd (27,000 m). Her captain promptly made visual contact. The two submarines quickly moved off in pursuit of the ships, while Darter made the first of three contact reports. At least one of these was picked up by a radio operator on Yamato, but Kurita failed to take appropriate antisubmarine precautions.[28]

Darter and Dace traveled on the surface at full power for several hours and gained a position ahead of Kurita's formation, with the intention of making a submerged attack at first light. This attack was unusually successful. At 05:24, Darter fired a salvo of six torpedoes, at least four of which hit Kurita's flagship, the heavy cruiser Atago. Ten minutes later, Darter made two hits on Atago's sister ship, Takao, with another spread of torpedoes. At 05:56, Dace made four torpedo hits on the heavy cruiser Maya (sister to Atago and Takao).[29]

Atago and Maya quickly sank.[30] Atago sank so rapidly that Kurita was forced to swim to survive. He was rescued by the Japanese destroyer Kishinami, and then later transferred to the battleship Yamato.[31]

Takao turned back to Brunei, escorted by two destroyers, and was followed by the two submarines. On 24 October, as the submarines continued to shadow the damaged cruiser, Darter ran aground on the Bombay Shoal. All efforts to get her off failed; she was abandoned; and her entire crew was rescued by Dace. Efforts to scuttle Darter over the course of the next week all failed, including torpedoes from Dace and Rock that hit the reef (and not Darter) and deck-gun shelling from Dace and later Nautilus. After multiple hits from his 6-inch deck guns, the Nautilus commander determined on 31 October that the equipment on Darter was only good for scrap and left her there. The Japanese did not bother with the wreck.

Takao retired to Singapore, being joined in January 1945 by Myōkō, as the Japanese deemed both crippled cruisers irreparable and left them moored in the harbor as floating anti-aircraft batteries.

Battle of the Sibuyan Sea (24 October 1944)

.jpg.webp)

Despite its great strength, Third Fleet was not well-placed to deal with the threat. On 22 October, Halsey had detached two of his carrier groups to the fleet base at Ulithi to take on provisions and rearm. When Darter's contact report came in, Halsey recalled Davison's group, but allowed Vice Admiral John S. McCain, with the strongest of TF 38's carrier groups, to continue towards Ulithi. Halsey finally recalled McCain on 24 October—but the delay meant the most powerful American carrier group played little part in the coming battle and Third Fleet was therefore effectively deprived of nearly 40% of its air strength for most of the engagement. On the morning of 24 October, only three groups were available to strike Kurita's force, and the one best positioned to do so—Gerald F. Bogan's Task Group 38.2 (TG 38.2)—was by mischance the weakest of the groups, containing only one large carrier—USS Intrepid—and the Independence-class light carriers Independence and Cabot.[32]

Meanwhile, Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi directed three waves of aircraft from his First Air Fleet based on Luzon against the carriers of Rear Admiral Frederick Sherman's TG 38.3 (whose aircraft were also being used to strike airfields in Luzon to prevent Japanese land-based air attacks on Allied shipping in Leyte Gulf). Each of Ōnishi's strike waves consisted of some 50 to 60 aircraft.[33]

.jpg.webp)

Most of the attacking Japanese planes were intercepted and shot down or driven off by Hellcats of Sherman's combat air patrol, most notably by two fighter sections from USS Essex led by Commander David McCampbell (who shot down a record nine of the attacking planes in this one action, after which he managed to return and land in extremis on USS Langley because the Essex's deck was too busy to accommodate him although he had run short of fuel).

_1944_10_24_1523explosion.jpg.webp)

However, one Japanese aircraft (a Yokosuka D4Y3 Judy) slipped through the defences, and at 09:38 hit the light carrier USS Princeton with a 551 lb (250 kg) armor-piercing bomb. Just prior to the bomb hitting the carrier ten fighter planes had landed on the flight deck from a previous mission and in the hangar deck six fully loaded and fueled Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers were waiting for the next mission. One of the torpedo bombers was directly hit by this bomb as it pierced the ship and exploded, triggering the other five torpedo bombers to also explode. The bomb hit the area of the ship where not only most of the torpedoes were stored but also bombs that were not stored securely.[34][35][36] The resulting explosion caused a severe fire in Princeton's hangar and her emergency sprinkler system failed to operate. As the fire spread rapidly, a series of secondary explosions followed. The fire was gradually brought under control, but at 15:23 there was an enormous explosion (probably in the carrier's bomb stowage aft), causing more casualties aboard Princeton, and even heavier casualties—233 dead and 426 wounded—aboard the light cruiser Birmingham which was coming back alongside to assist with the firefighting. Birmingham and the three destroyers Morrison, USS Gatling (DD-671) and Irwin remained with the stricken carrier after she fell out of formation. The destroyers initially attempted to come alongside and spray the burning carrier to help the ship's crew suppress the fires, but they repeatedly collided with Princeton in the heavy seas. Birmingham then came alongside instead, as her larger hull could better absorb collisions. Birmingham was so badly damaged, she was forced to retire. Reno, Morrison, and Irwin were also damaged. All efforts to save Princeton failed, and after the remaining crew members were evacuated, she was finally scuttled—torpedoed by the light cruiser Reno—at 17:50.[37] Of Princeton's crew, 108 men were killed, while 1,361 survivors were rescued by nearby ships. USS Princeton was the largest American ship lost during the battles around Leyte Gulf, and the only Independence-class fast carrier sunk in combat during the war. 17 Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters and 12 Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers went down with Princeton.[38]

Planes from the carriers Intrepid and Cabot of Bogan's group attacked at about 10:30 scoring hits on the battleships Nagato, Yamato, and Musashi, and badly damaging the heavy cruiser Myōkō which retired to Borneo via Coron Bay. A second wave from Intrepid, Essex and Lexington later attacked, with VB-15 Helldivers and VF-15 Hellcats from Essex, scoring another 10 hits on Musashi. As she withdrew, listing to port, a third wave from Enterprise and Franklin hit her with an additional 11 bombs and eight torpedoes.[39] After being struck by at least 17 bombs and 19 torpedoes, Musashi finally capsized and sank at about 19:35.[40]

.jpg.webp)

In all, five fleet carriers and one light carrier of Third Fleet flew 259 sorties with bombs carried by Helldivers and torpedoes launched by TBF Avengers against Center Force on 24 October, but this weight of attack was not nearly sufficient to neutralize the threat from Kurita. The largest effort of the Sibuyan Sea attack was directed against just one battleship, Musashi, which was sunk, and the cruiser Myōkō was also crippled by an aerial torpedo. Nevertheless, every other ship in Kurita's force remained battleworthy and able to advance.[40] It would be the desperate action and great sacrifice of the much weaker force of six slow escort carriers, three destroyers, four destroyer escorts, and 400 aircraft at the Battle off Samar, utterly lacking in credible weapons to sink armored ships, to stop Kurita. It also contrasts with the 527 sorties flown by Third Fleet against Ozawa's much weaker carrier decoy Northern Force on the following day.

Kurita turned his fleet around to get out of range of the aircraft, passing the crippled Musashi as his force retreated. Halsey assumed that this retreat signified that his threat was dealt with for the time being. Kurita, however, waited until 17:15 before turning around again to head for the San Bernardino Strait. As a result of a momentous decision taken by Admiral Halsey and some unclear communication of his plans, Kurita was able to proceed through the San Bernardino Strait during the night to make an unexpected and dramatic appearance off the coast of Samar the following morning, directly threatening the Leyte landings.[41]

Task Force 34 / San Bernardino Strait

After the Japanese Southern and Center forces had been detected, but before it had been engaged or Ozawa's carriers had been located, Halsey and the staff of Third Fleet, aboard the battleship New Jersey, prepared a contingency plan to deal with the threat from Kurita's Center Force. Their intention was to cover San Bernardino Strait with a powerful task force of fast battleships supported by two of Third Fleet's equally swift carrier groups. The battleship force was to be designated Task Force 34 (TF 34) and to consist of four battleships, five cruisers, and 14 destroyers under the command of Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee. Rear Admiral Ralph E. Davison of TG 38.4 was to be in overall command of the supporting carrier groups.[42]

At 15:12 on 24 October, Halsey sent an ambiguously worded telegraphic radio message to his subordinate task group commanders giving details of this contingency plan:

BATDIV 7 BILOXI, VINCENNES, MIAMI, DESRON 52 LESS STEVEN POTTER, FROM TG 38.2 AND WASHINGTON, ALABAMA, WICHITA, NEW ORLEANS, DESDIV 100, PATTERSON, BAGLEY FROM TG 38.4 WILL BE FORMED AS TASK FORCE 34 UNDER VICE ADMIRAL LEE, COMMANDER BATTLE LINE. TF 34 TO ENGAGE DECISIVELY AT LONG RANGES. CTG 38.4 CONDUCT CARRIERS OF TG 38.2 AND TG 38.4 CLEAR OF SURFACE FIGHTING. INSTRUCTIONS FOR TG 38.3 AND TG 38.1 LATER. HALSEY, OTC IN NEW JERSEY.[43]

Halsey sent information copies of this message to Admiral Nimitz at Pacific Fleet headquarters and Admiral King in Washington, but he did not include Admiral Kinkaid (Seventh Fleet) as an information addressee.[44] The message was picked up by Seventh Fleet anyway as it was common for admirals to direct radio operators to copy all message traffic they detected whether intended for them or not. Because Halsey intended TF 34 as a contingency to be formed and detached when he ordered it, by writing "will be formed," he meant the future tense, but he neglected to say when TF 34 would be formed or under what circumstances. This omission led Admiral Kinkaid of Seventh Fleet to believe Halsey was speaking in the present tense, so he concluded TF 34 had been formed and would take station off the San Bernardino Strait. Kinkaid's light escort carrier group, lacking battleships for naval action and set up to attack ground troops and submarines, not capital ships, positioned itself south of the strait to support the invasion force. Admiral Nimitz, in Pearl Harbor, reached exactly the same conclusion.

Halsey did send out a second message at 17:10 clarifying his intentions in regard to TF 34:

IF THE ENEMY SORTIES [through San Bernardino Strait] TF 34 WILL BE FORMED WHEN DIRECTED BY ME.[45][46]

Unfortunately, Halsey sent this second message by voice radio, so Seventh Fleet did not intercept it (due to the range limitations of the ship-to-ship voice radio networks in use at the time) and Halsey did not follow up with a telegraphic message to Nimitz or King, or vitally, Kinkaid. The serious misunderstanding caused by Halsey's imperfect wording of his first message and his failure to notify Nimitz, King, or Kinkaid of his second clarifying message had a profound influence on the subsequent course of the battle as Kurita's major force almost overwhelmed Kinkaid's unprepared lighter force on the doorstep of the Leyte landings.[47][45]

Halsey's decision (24 October 1944)

Third Fleet's aircraft failed to locate Ozawa's Northern Force until 16:40 on 24 October. This was largely because Third Fleet had been preoccupied with attacking Kurita's sizable Center Force and defending itself against the Japanese air strikes from Luzon. Thus the one Japanese force that wanted to be discovered – Ozawa's tempting decoy of a large carrier group, which actually had only 108 aircraft – was the only force the Americans had not been able to find. On the evening of 24 October, Ozawa intercepted a (mistaken) American communication describing Kurita's withdrawal; he therefore began to withdraw, too. However, at 20:00, Toyoda ordered all his forces to attack "counting on divine assistance." Trying to draw Third Fleet's attention to his decoy force, Ozawa reversed course again and headed southward towards Leyte.

Halsey fell for the Japanese decoy, convinced the Northern Force constituted the main Japanese threat, and he was determined to seize what he saw as a golden opportunity to destroy Japan's last remaining carrier strength. Believing Center Force had been neutralized by Third Fleet's air strikes earlier in the day in the Sibuyan Sea, and its remnants were retiring, Halsey radioed (to Nimitz and Kinkaid):

CENTRAL FORCE HEAVILY DAMAGED ACCORDING TO STRIKE REPORTS.

AM PROCEEDING NORTH WITH THREE GROUPS TO ATTACK CARRIER FORCES AT DAWN[48]

The words "with three groups" proved dangerously misleading. In the light of the intercepted 15:12 24 October "…will be formed as Task Force 34" message from Halsey, Admiral Kinkaid and his staff assumed, as did Admiral Nimitz at Pacific Fleet headquarters, that TF 34—commanded by Vice Admiral Lee—had now been formed as a separate entity. They assumed that Halsey was leaving this powerful surface force guarding the San Bernardino Strait (and covering Seventh Fleet's northern flank), while he took his three available carrier groups northwards in pursuit of the Japanese carriers. But Task Force 34 had not been detached from his other forces, and Lee's battleships were on their way northwards with Third Fleet's carriers. As Woodward wrote: "Everything was pulled out from San Bernardino Strait. Not so much as a picket destroyer was left".[49]

Warning signs ignored

Halsey and his staff officers ignored information from a night reconnaissance aircraft operating from the light carrier Independence that Kurita's powerful surface force had turned back towards the San Bernardino Strait and that, after a long blackout, the navigation lights in the strait had been turned on. When Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan—commanding TG 38.2—radioed this information to Halsey's flagship, he was rebuffed by a staff officer, who tersely replied "Yes, yes, we have that information." Vice Admiral Lee, who had correctly deduced that Ozawa's force was on a decoy mission and indicated this in a blinker message to Halsey's flagship, was similarly rebuffed.

Commodore Arleigh Burke and Commander James H. Flatley of Mitscher's staff had come to the same conclusion. They were sufficiently worried about the situation to wake Mitscher, who asked, "Does Admiral Halsey have that report?" On being told that Halsey did, Mitscher—knowing Halsey's temperament—commented, "If he wants my advice he'll ask for it" and went back to sleep.[50]

The entire available strength of Third Fleet continued to steam northwards towards Ozawa's decoy force, leaving the San Bernardino Strait completely unguarded. Nothing lay between the battleships of Kurita's Center Force and the American landing vessels, except for Kinkaid's vulnerable escort carrier group off the coast of Samar.

Battle of Surigao Strait (25 October 1944)

The Battle of Surigao Strait is significant as the last battleship-to-battleship action in history. The Battle of Surigao Strait was one of only two battleship-versus-battleship naval battles in the entire Pacific campaign of World War II (the other being the naval battle during the Guadalcanal Campaign, where Washington sank the Japanese battleship Kirishima). It is also the most recent battle in which one force (in this case, the U.S. Navy) was able to "cross the T" of its opponent. However, by the time that the battleship action was joined, the Japanese line was very ragged and consisted of only one battleship (Yamashiro), one heavy cruiser, and one destroyer, so that the "crossing of the T" was notional and had little effect on the outcome of the battle.[51][52]

Japanese forces

Nishimura's "Southern Force" consisted of the old battleships Yamashiro (flag) and Fusō, the heavy cruiser Mogami, and four destroyers,[53] Shigure, Michishio, Asagumo and Yamagumo. This task force left Brunei after Kurita at 15:00 on 22 October, turning eastward into the Sulu Sea and then northeasterly past the southern tip of Negros Island into the Mindanao Sea. Nishimura then proceeded northeastward with Mindanao Island to starboard and into the south entrance to the Surigao Strait, intending to exit the north entrance of the Strait into Leyte Gulf, where he would add his firepower to that of Kurita's force.

The Japanese Second Striking Force was commanded by Vice Admiral Kiyohide Shima and comprised heavy cruisers Nachi (flag) and Ashigara, the light cruiser Abukuma, and the destroyers Akebono, Ushio, Kasumi, and Shiranui.

The Japanese Southern Force was attacked by U.S. Navy bombers on 24 October but sustained only minor damage.

Nishimura was unable to synchronize his movements with Shima and Kurita because of the strict radio silence imposed on the Center and Southern Forces. When he entered the Surigao Strait at 02:00, Shima was 25 nautical miles (29 mi; 46 km) behind him, and Kurita was still in the Sibuyan Sea, several hours from the beaches at Leyte.

Engagement

As the Japanese Southern Force approached the Surigao Strait, it ran into a deadly trap set by Seventh Fleet. Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf had a substantial force comprising

- six battleships: West Virginia, Maryland, Mississippi, Tennessee, California, and Pennsylvania, which carried 48 14-inch (356 mm) and 16 16-inch (406 mm) guns;

- four heavy cruisers USS Louisville (flagship), Portland, Minneapolis, and HMAS Shropshire, which carried 35 8-inch (203 mm) guns;

- four light cruisers Denver, Columbia, Phoenix, and Boise, which carried 54 6-inch (152 mm) guns; and

- 28 destroyers and 39 motor torpedo boats (Patrol/Torpedo (PT) boats) with smaller guns and torpedoes.

Five of the six battleships had been sunk or damaged in the attack on Pearl Harbor and subsequently repaired or, in the cases of Tennessee, California, and West Virginia, rebuilt. The sole exception was Mississippi, which had been in Iceland on convoy-escort duty at that time. To pass through the narrows and reach the invasion shipping, Nishimura would have to run the gauntlet of torpedoes from the PT boats and destroyers before advancing into the concentrated fire of 14 battleships and cruisers deployed across the far mouth of the strait.[54]

At 22:36, PT-131 (Ensign Peter Gadd) was operating off Bohol when it made contact with the approaching Japanese ships. The PT boats made repeated attacks for more than three and a half hours as Nishimura's force streamed northward. No torpedo hits were scored, but the PT boats did send contact reports which were of use to Oldendorf and his force.[55]

Nishimura's ships passed unscathed through the gauntlet of PT boats. However, their luck ran out a short time later, as they were subjected to devastating torpedo attacks from the American destroyers deployed on both sides of their axis of advance. At about 03:00, both Japanese battleships were hit by torpedoes. Yamashiro was able to steam on, but Fusō was torpedoed by USS Melvin and fell out of formation, sinking forty minutes later. Two of Nishimura's four destroyers were sunk; the destroyer Asagumo was hit and forced to retire, but later sank.[56]

Sinking of Fusō

The traditional account of the sinking of Fusō was that she exploded into two halves that remained floating for some time. However, Fusō survivor Hideo Ogawa, interrogated in 1945, in an article on the battleship's last voyage, stated: "Shortly after 0400 the ship capsized slowly to starboard and Ogawa and others were washed away,"[57] without specifically mentioning the bisection. Fusō was hit on the starboard side by two or possibly three torpedoes. One of these started an oil fire, and as the fuel used by IJN ships was poorly refined and easily ignited, burning patches of fuel could have led to the description from Allied observers of Fusō "blowing up". However, battleships were known sometimes to be cut into two or even three sections which could remain afloat independently, and Samuel Morison states that the bow half of Fusō was sunk by gunfire from Louisville, and the stern half sank off Kanihaan Island.

_firing_during_the_Battle_of_Surigao_Strait_in_October_1944.jpg.webp)

Battle continues

At 03:16, West Virginia's radar picked up the surviving ships of Nishimura's force at a range of 42,000 yd (24 mi; 21 nmi; 38 km). West Virginia tracked them as they approached in the pitch black night. At 03:53, she fired the eight 16 in (406 mm) guns of her main battery at a range of 22,800 yd (13.0 mi; 11.3 nmi; 20.8 km), striking Yamashiro with her first salvo. She went on to fire a total of 93 shells. At 03:55, California and Tennessee joined in, firing 63 and 69 shells, respectively, from their 14 in (356 mm) guns. Radar fire control allowed these American battleships to hit targets from a distance at which the Japanese battleships, with their inferior fire control systems, could not return fire.[54][52]

History's last salvo

The other three U.S. battleships also had difficulty as they were equipped with less advanced gunnery radar. Pennsylvania was unable to find a target and her guns remained silent.[58] Maryland eventually succeeded in visually ranging on the splashes of the other battleships' shells, and then fired a total of 48 16 in (406 mm) projectiles. Mississippi only fired once in the battle-line action, a full salvo of twelve 14-inch shells. This was the last salvo ever fired by a battleship against another battleship in history, closing a significant chapter in naval warfare.[59]

Yamashiro and Mogami were crippled by a combination of 16-inch and 14-inch armor-piercing shells, as well as the fire of Oldendorf's flanking cruisers. The cruisers that had the latest radar equipment fired well over 2,000 rounds of armor-piercing 6-inch and 8-inch shells. Louisville (Oldendorf's flagship) fired 37 salvos—333 rounds of 8-inch shells. The Japanese command had apparently lost grasp of the tactical picture, with all ships firing all batteries in several directions, "frantically showering steel through 360°."[60] Shigure turned and fled but lost steering and stopped dead. At 04:05 Yamashiro was struck by a torpedo fired by the destroyer Bennion,[61][62] and suddenly sank at about 04:20, with Nishimura on board. Mogami and Shigure retreated southwards down the Strait. The destroyer Albert W. Grant was hit by friendly fire during the night battle, but did not sink.

The rear of the Japanese Southern Force—the "Second Striking Force" commanded by Vice Admiral Shima—had departed from Mako and approached Surigao Strait about 40 mi (35 nmi; 64 km) astern of Nishimura. Shima's run was initially thrown into confusion by his force nearly running aground on Panaon Island after failing to factor the outgoing tide into their approach. Japanese radar was almost useless due to excessive reflections from the many islands. The American radar was equally unable to detect ships in these conditions, especially PT boats, but PT-137 hit the light cruiser Abukuma with a torpedo that crippled her and caused her to fall out of formation. Shima's two heavy cruisers, Nachi and Ashigara, and four destroyers[63] next encountered remnants of Nishimura's force. Shima saw what he thought were the wrecks of both Nishimura's battleships and ordered a retreat. His flagship Nachi collided with Mogami, flooding Mogami's steering room and causing her to fall behind in the retreat; she was further damaged by American carrier aircraft the next morning, abandoned and scuttled by a torpedo from Akebono.

First kamikaze attacks of the Pacific War

While the Battle off Samar was raging between the Japanese surface fleet and Taffy 3, Taffy 1's escort carriers were supporting the American surface ships after the Battle of Surigao Strait when daylight broke (the nighttime Surigao Strait action meant no carrier aircraft could participate until after dawn, during which the defeated Japanese southern fleet was in full retreat). As a result of Taffy 1 being so far south of Samar not many Taffy 1 airplanes participated in the Battle off Samar. While in the air southwest of Leyte Gulf the aircraft and ships of Taffy 1 were immediately ordered to assist Taffy 3 off of Samar but they had to return to the escort carriers to refuel and rearm.

After the carrier aircraft returned from aerial attacks on the retreating Japanese naval forces from Surigao Strait the Japanese launched the first pre-planned kamikaze (suicide "special attack" planes) attacks of World War II against Taffy 1 from Davao. The escort carrier Santee was hit by a kamikaze first, killing 16 crewmen. A Japanese submarine also successfully launched a torpedo at Santee, striking her starboard side. 4 Avenger torpedo bombers and 2 Wildcat fighters on Santee were destroyed in this attack. Emergency repairs saved Santee from sinking.

The escort carrier Suwannee was shortly afterwards hit by a kamikaze, killing 71 sailors. Suwannee was hit by another kamikaze around noon on 26 October that caused even more damage and killed 36 more crewmen. This second kamikaze strike caused a large fire that was not extinguished until nine hours later. A total of 107 sailors were killed and over 150 were wounded on Suwannee in the kamikaze attacks on 25–26 October. Five Avenger torpedo bombers and 9 Hellcat fighters on Suwannee were destroyed.[64][65][66]

Results

Of Nishimura's seven ships, only Shigure survived long enough to escape the debacle,[67] but eventually succumbed to the American submarine Blackfin on 24 January 1945, which sank her off Kota Bharu, Malaya, with 37 dead.[52] Shima's ships did survive the Battle of Surigao Strait, but they were sunk in further engagements around Leyte. The Southern Force provided no further threat to the Leyte landings.

Battle off Samar (25 October 1944)

Prelude

Halsey's decision to take all the available strength of Third Fleet northwards to attack the carriers of the Japanese Northern Force had left San Bernardino Strait completely unguarded.

Senior officers in Seventh Fleet (including Kinkaid and his staff) generally assumed Halsey was taking his three available carrier groups northwards (McCain's group, the strongest in Third Fleet, was still returning from the direction of Ulithi), but leaving the battleships of TF 34 covering the San Bernardino Strait against the Japanese Center Force. In fact, Halsey had not yet formed TF 34, and all six of Willis Lee's battleships were on their way northwards with the carriers, as well as every available cruiser and destroyer of Third Fleet.

Kurita's Center Force therefore emerged unopposed from San Bernardino Strait at 03:00 on 25 October and steamed southward along the coast of the island of Samar. In its path stood only Seventh Fleet's three escort carrier units (call signs 'Taffy' 1, 2, and 3), with a total of sixteen small, very slow, and unarmored escort carriers, which carried up to 28 airplanes each, protected by a screen of lightly armed and unarmored destroyers and smaller destroyer escorts (DEs). Despite the losses in the Palawan Passage and Sibuyan Sea actions, the Japanese Center Force was still very powerful, consisting of four battleships (including the giant Yamato), six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and eleven destroyers.[68]

Battle

Kurita's force caught Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague's Task Unit 77.4.3 ('Taffy 3') by surprise. Sprague directed his carriers to launch their planes, then ran for the cover of a rain squall to the east. He ordered the destroyers and DEs to make a smoke screen to conceal the retreating carriers.

Kurita, unaware that Ozawa's decoy plan had succeeded, assumed he had found a carrier group from Halsey's Third Fleet. Having just redeployed his ships into anti-aircraft formation, he further complicated matters by ordering a "General Attack", which called for his fleet to split into divisions and attack independently.[8]

The destroyer USS Johnston was the closest to the enemy. On his own initiative, Lieutenant Commander Ernest E. Evans steered his hopelessly outclassed ship into the Japanese fleet at flank speed. Johnston fired its torpedoes at the heavy cruiser Kumano, damaging her and forcing her out of line. Seeing this, Sprague gave the order "small boys attack", sending the rest of Taffy 3's screening ships into the fray. Taffy 3's two other destroyers, Hoel and Heermann, and the destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts, attacked with suicidal determination, drawing fire and disrupting the Japanese formation as ships turned to avoid their torpedoes. As the ships approached the enemy columns, Lt. Cdr. Copeland of Samuel B. Roberts told all hands via bull horn that this would be "a fight against overwhelming odds from which survival could not be expected."[69] As the Japanese fleet continued to approach, Hoel and Roberts were hit multiple times, and quickly sank. After expending all of its torpedoes, Johnston continued to fight with its 5-inch guns, until it was sunk by a group of Japanese destroyers.

As they were preparing their aircraft for attack, the escort carriers returned the Japanese fire with all the firepower they had – one 5-inch gun per carrier. The officer in tactical command had instructed the carriers to "open with pea shooters," and each ship took an enemy vessel under fire as soon as it came within range. Fanshaw Bay fired on a cruiser, and is believed to have registered five hits, one amid the superstructure that caused smoke. Kalinin Bay targeted a Myōkō-class heavy cruiser, claiming a hit on the cruiser's No. 2 turret, with a second just below the first. Gambier Bay sighted a cruiser, and claimed at least three hits. White Plains reported hits on multiple targets, two between the superstructure and forward stack and another on the No. 1 turret of a heavy cruiser.[70]

Meanwhile, Rear Admiral Thomas Sprague (no relation to Clifton) ordered the sixteen escort carriers in his three task units to immediately launch all their aircraft – totaling 450 planes – equipped with whatever weapons they had available, even if these were only machine guns or depth charges. The escort carriers had planes more suited for patrol and anti-submarine duties, including older models such as the FM-2 Wildcat, although they also had the TBM Avenger torpedo bombers, in contrast to Halsey's fleet carriers which had the newest aircraft with ample anti-shipping ordnance. However, the fact that the Japanese force had no air cover meant that Sprague's planes could attack unopposed by Japanese fighter aircraft. Consequently, the air counterattacks were almost unceasing, and some, especially several of the strikes launched from Felix Stump's Task Unit 77.4.2 (Taffy 2), were heavy.

The carriers of Taffy 3 turned south and retreated through the shellfire. Gambier Bay, at the rear of the American formation, became the focus of the battleship Yamato and sustained multiple hits before capsizing at 09:07. 4 Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers went down with Gambier Bay.[71] Several other carriers were damaged but were able to escape.

Admiral Kurita withdraws

The ferocity of the American defense seemingly confirmed the Japanese assumption that they were engaging major fleet units rather than merely escort carriers and destroyers. The confusion of the "General Attack" order was compounded by the air and torpedo attacks, when Kurita's flagship Yamato turned north to evade torpedoes and lost contact with the battle.

Kurita abruptly broke off the fight and gave the order 'all ships, my course north, speed 20', apparently to regroup his disorganized fleet. Kurita's battle report stated he had received a message indicating a group of American carriers was steaming north of him. Preferring to expend his fleet against capital ships rather than transports, Kurita set out in pursuit and thereby lost his opportunity to destroy the shipping fleet in Leyte Gulf, and disrupt the vital landings at Leyte. After failing to intercept the non-existent carriers, which were much farther north, Kurita finally retreated towards San Bernardino Strait. Three of his heavy cruisers had been sunk, and the determined resistance had convinced him that persisting with his attack would only cause further Japanese losses.

Poor communication between the separate Japanese forces and a lack of air reconnaissance meant that Kurita was never informed that the deception had been successful, and that only a small and outgunned force stood between his battleships and the vulnerable transports of the invasion fleet. Thus, Kurita remained convinced that he had been engaging elements of Third Fleet, and it would only be a matter of time before Halsey surrounded and annihilated him.[8] Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague wrote to his colleague Aubrey Fitch after the war, "I ... stated [to Admiral Nimitz] that the main reason they turned north was that they were receiving too much damage to continue and I am still of that opinion and cold analysis will eventually confirm it."[68]

Almost all of Kurita's surviving force escaped. Halsey and Third Fleet's battleships returned too late to cut him off. Nagato and Kongō had been moderately damaged by air attack from Taffy 3's escort carriers. Kurita had begun the battle with five battleships. On their return to their bases, only Yamato and Haruna remained battleworthy.

As the desperate surface action was coming to an end, Vice Admiral Takijirō Ōnishi put his Japanese Special Attack Units into operation from bases on Luzon, launching kamikaze attacks against the Allied ships in Leyte Gulf and the escort carrier units off Samar. This was the second ever organized kamikaze attack by the Japanese in World War II after the kamikaze attack on Taffy 1 a few hours earlier off of Surigao Strait. The escort carrier St. Lo of Taffy 3 was hit by a kamikaze aircraft and sank after a series of internal explosions. 6 Grumman FM-2 Wildcat fighters and 5 Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers went down with St. Lo. Three other Taffy 3 escort carriers, USS Kalinin Bay, USS Kitkun Bay and White Plains, were also damaged in the same kamikaze attack.[72]

Battle off Cape Engaño (25–26 October 1944)

Vice-Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa's "Northern Force", built around the four aircraft carriers of the 3rd Carrier Division (Zuikaku—the last survivor of the six carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941—and the light carriers Zuihō, Chitose, and Chiyoda), included two World War I battleships partially converted to carriers (Hyūga and Ise—the two aft turrets had been replaced by a hangar, aircraft handling deck and catapult, but neither ship carried any aircraft in this battle), three light cruisers (Ōyodo, Tama, and Isuzu), and nine destroyers. Ozawa's carrier group was a decoy force, divested of all but 108 aircraft, intended to lure the American fleet away from protecting the transports at the landing beaches on Leyte island.

Ozawa's force was not located until 16:40 on 24 October, largely because Sherman's TG 38.3—the northernmost of Halsey's groups and responsible for searches in this sector—had been preoccupied with the action in the Sibuyan Sea, and in defending itself against the Japanese air strikes from Luzon. Thus Ozawa's group—the one Japanese force that wanted to be discovered—was the only force the Americans had not been able to find. The force that Halsey was taking north with him—three groups of Mitscher's TF 38—was overwhelmingly stronger than the Japanese Northern Force. Between them, these groups had five large fleet carriers (Intrepid, Franklin, Lexington, Enterprise and Essex), five light carriers (Independence, Belleau Wood, Langley, Cabot and San Jacinto), six modern battleships (Alabama, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Jersey, South Dakota and Washington), eight cruisers (two heavy and six light), and 41 destroyers. The air groups of the ten U.S. carriers present contained 600–1,000 aircraft.[73]

At 02:40 on 25 October, Halsey detached TF 34, built around Third Fleet's six battleships and commanded by Vice Admiral Lee. As dawn approached, the ships of Task Force 34 drew ahead of the carrier groups. Halsey intended Mitscher to make air strikes followed by the heavy gunfire of Lee's battleships.[74]

Around dawn on 25 October, Ozawa launched 75 aircraft, the bulk of his few aircraft, to attack Third Fleet. Most were shot down by American combat air patrols, and no damage was done to the U.S. ships. A few Japanese planes survived and made their way to land bases on Luzon.

During the night, Halsey had passed tactical command of TF 38 to Admiral Mitscher, who ordered the American carrier groups to launch their first strike wave, of 180 aircraft, at dawn—before the Northern Force had been located. When the search aircraft made contact at 07:10, this strike wave was orbiting ahead of the task force. At 08:00, as the attack went in, its escorting fighters destroyed Ozawa's combat air patrol of about 30 planes. The U.S. air strikes continued until the evening, by which time TF 38 had flown 527 sorties against the Northern Force, sinking Zuikaku, the light carriers Chitose and Zuihō, and the destroyer Akizuki, all with heavy loss of life. The light carrier Chiyoda and the cruiser Tama were crippled. Ozawa transferred his flag to the light cruiser Ōyodo.

Crisis – U.S. Seventh Fleet's calls for help

Shortly after 08:00 on 25 October, desperate messages calling for assistance began to come in from Seventh Fleet, which had been engaging Nishimura's "Southern Force" in battle in Surigao Strait since 02:00. One message from Kinkaid, sent in plain language, read: "My situation is critical. Fast battleships and support by air strikes may be able to keep enemy from destroying CVEs and entering Leyte." Halsey recalled in his memoirs that he was shocked at this message, recounting that the radio signals from Seventh Fleet had come in at random and out of order because of a backlog in the signals office. It seems that he did not receive this vital message from Kinkaid until around 10:00. Halsey later claimed he knew Kinkaid was in trouble, but he had not dreamed of the seriousness of this crisis.

One of the most alarming signals from Kinkaid reported, after their action in Surigao Strait, Seventh Fleet's own battleships were critically low on ammunition. Even this failed to persuade Halsey to send any immediate assistance to Seventh Fleet.[75][76][77] In fact, Seventh Fleet's battleships were not as short of ammunition as Kinkaid's signal implied,[78] but Halsey did not know that.

From 3,000 mi (2,600 nmi; 4,800 km) away in Pearl Harbor, Admiral Nimitz had been monitoring the desperate calls from Taffy 3, and sent Halsey a terse message: "TURKEY TROTS TO WATER GG FROM CINCPAC ACTION COM THIRD FLEET INFO COMINCH CTF SEVENTY-SEVEN X WHERE IS RPT WHERE IS TASK FORCE THIRTY FOUR RR THE WORLD WONDERS." The first four words and the last three were "padding" used to confuse enemy cryptanalysis (the beginning and end of the true message were marked by double consonants). The communications staff on Halsey's flagship correctly deleted the first section of padding but mistakenly retained the last three words in the message finally handed to Halsey. The last three words—probably selected by a communications officer at Nimitz's headquarters—may have been meant as a loose quote from Tennyson's poem on "The Charge of the Light Brigade",[79] suggested by the coincidence that this day, 25 October, was the 90th anniversary of the Battle of Balaclava—and was not intended as a commentary on the current crisis off Leyte. Halsey, however, when reading the message, thought that the last words—"THE WORLD WONDERS"—were a biting piece of criticism from Nimitz, threw his cap to the deck and broke into "sobs of rage". Rear Admiral Robert Carney, his chief of staff, confronted him, telling Halsey "Stop it! What the hell's the matter with you? Pull yourself together."

Eventually, at 11:15, more than three hours after the first distress messages from Seventh Fleet had been received by his flagship, Halsey ordered TF 34 to turn around and head southwards towards Samar. At this point, Lee's battleships were almost within gun range of Ozawa's force. Two and a half hours were then spent refuelling TF 34's accompanying destroyers.[80]

After this succession of delays it was too late for TF 34 to give any practical help to Seventh Fleet, other than to assist in picking up survivors from Taffy 3, and too late even to intercept Kurita's force before it made its escape through San Bernardino Strait.

Nevertheless, at 16:22, in a desperate and even more belated attempt to intervene in the events off Samar, Halsey formed a new task group—TG 34.5—under Rear Admiral Oscar C. Badger II,[81] built around Third Fleet's two fastest battleships—Iowa and New Jersey, both capable of a speed of more than 32 kn (59 km/h; 37 mph)—and TF 34's three cruisers and eight destroyers, and sped southwards, leaving Lee and the other four battleships to follow. As Morison observes, if Badger's group had succeeded in intercepting the Japanese Center Force it may have been outgunned by Kurita's battleships.[82]

Cruisers and destroyers of TG 34.5, however, caught the Japanese destroyer Nowaki—the last straggler from Center Force—off San Bernardino Strait, and sank her with all hands, including the survivors from Chikuma.

Final actions

When Halsey turned TF 34 southwards at 11:15, he detached a task group of four of its cruisers and nine of its destroyers under Rear Admiral DuBose, and reassigned this group to TF 38. At 14:15, Mitscher ordered DuBose to pursue the remnants of the Japanese Northern Force. His cruisers finished off the light carrier Chiyoda at around 17:00, and at 20:59 his ships sank the destroyer Hatsuzuki after a very stubborn fight.[83]

When Ozawa learned of the deployment of DuBose's relatively weak task group, he ordered battleships Ise and Hyūga to turn southwards and attack it, but they failed to locate DuBose's group, which they heavily outgunned. Halsey's withdrawal of all six of Lee's battleships in his attempt to assist Seventh Fleet had now rendered TF 38 vulnerable to a surface counterattack by the decoy Northern Force.

At about 23:10, the American submarine Jallao torpedoed and sank the light cruiser Tama of Ozawa's force.[84] This was the last act of the Battle off Cape Engaño, and—apart from some final air strikes on the retreating Japanese forces on 26 October—the conclusion of the Battle for Leyte Gulf.

Weighing the decisions of Halsey

Criticism

Halsey was questioned for his decision to take TF 34 north in pursuit of Ozawa, and for failing to detach it when Kinkaid first appealed for help. A piece of U.S. Navy slang for Halsey's actions is Bull's Run, a phrase combining Halsey's newspaper nickname "Bull" (he was known as "Bill" Halsey) with an allusion to the Battle of Bull Run in the American Civil War, which Union troops lost due to poor organization and lack of decisive action.

Clifton Sprague—commander of Task Unit 77.4.3 in the Battle off Samar—was later bitterly critical of Halsey's decision, and of his failure to clearly inform Kinkaid and Seventh Fleet that their northern flank was no longer protected: "In the absence of any information ... it was logical to assume that our northern flank could not be exposed without ample warning." Regarding Halsey's failure to turn TF 34 southwards when Seventh Fleet's first calls for assistance off Samar were received, Morison writes:

If TF 34 had been detached a few hours earlier, after Kinkaid's first urgent request for help, and had left the destroyers behind, since their fueling caused a delay of over two and a half hours, a powerful battle line of six modern battleships under the command of Admiral Lee, the most experienced battle squadron commander in the Navy, would have arrived off the San Bernardino Strait in time to have clashed with Kurita's Center Force ... Apart from the accidents common in naval warfare, there is every reason to suppose that Lee would have "crossed the T" and completed the destruction of Center Force. ... The mighty gunfire of Third Fleet's Battle Line, greater than that of the whole Japanese Navy, was never brought into action except to finish off one or two crippled light ships.[85][lower-alpha 5]

Vice Admiral Lee said in his action report as Commander of TF 34: "No battle damage was incurred nor inflicted on the enemy by vessels while operating as Task Force Thirty-Four."[42]

Halsey's defense

In his dispatch after the battle, Halsey justified the decision to go North as follows:

Searches by my carrier planes revealed the presence of the Northern carrier force on the afternoon of 24 October, which completed the picture of all enemy naval forces. As it seemed childish to me to guard statically San Bernardino Strait, I concentrated TF 38 during the night and steamed north to attack the Northern Force at dawn. I believed that the Center Force had been so heavily damaged in the Sibuyan Sea that it could no longer be considered a serious menace to Seventh Fleet.[88][89]

Halsey also argued that he had feared leaving TF 34 to defend the strait without carrier support as that would have left it vulnerable to attack from land-based aircraft, while leaving one of the fast carrier groups behind to cover the battleships would have significantly reduced the concentration of air power going north to strike Ozawa.

However, Morison states that Admiral Lee said after the battle that he would have been fully prepared for the battleships to cover the San Bernardino Strait without air cover,[90] as each of the escort carriers of TF 77 had up to 28 planes on them, but little surface ship protection, from Kurita's traditional naval force, which lacked air support.

Potential mitigating factors

The fact that Halsey was aboard one of the two fast battleships (New Jersey), and "would have had to remain behind" with TF 34 while the bulk of his fleet charged northwards, may have influenced his decision, but it would have been perfectly feasible to have taken one or both of Third Fleet's two fastest battleships with some or all of the large carriers in the pursuit of Ozawa, while leaving the rest of the battle line off the San Bernardino Strait. Halsey's original plan for TF 34 was for four, not all six, of Third Fleet's battleships.

Halsey was certainly philosophically against dividing his forces. He believed strongly in the current naval doctrine of concentration, as indicated by his writings both before World War II and in his subsequent articles and interviews defending his actions.[91] In addition, Halsey may well have been influenced by the recent criticisms of Admiral Raymond Spruance, who was criticized for excessive caution in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, allowing the bulk of the Japanese fleet to escape. Halsey's chief of staff, Rear Admiral Robert "Mick" Carney, was also wholeheartedly in favor of taking all of Third Fleet's available forces northwards to attack the Japanese carriers.

Halsey also did not believe reports of just how badly compromised Japan's naval air power was, and had no idea that Ozawa's decoy force only had 100 aircraft. Although in a letter to Nimitz just three days before the Battle off Samar, Halsey wrote that Mitscher believed "Jap naval air was wiped out",[92] which Spruance and Mitscher concluded from shooting down over 433 carrier based planes at the Marianas Turkey Shoot,[92] Halsey ignored Mitscher's insights, and later stated that he did not want to be "shuttle bombed" (whereby attacking planes from Ozawa's force could refuel and rearm at bases on land, allowing them to attack again on the return flight), or to give them a "free shot" at the U.S. forces in Leyte Gulf.[91]

Halsey may have considered Kurita's damaged battleships and cruisers, lacking carrier support, as little threat, but ironically, through his own failures to adequately communicate his intentions, he managed to demonstrate that unsupported battleships could still be dangerous.[93]

In his master's thesis submitted at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Lieutenant Commander Kent Coleman argues that the division of command hierarchies of Third Fleet, under Halsey reporting to Nimitz, and Seventh Fleet, under Kinkaid reporting to General MacArthur, was the primary contributor to the near-success of Kurita's attack. Coleman concludes that "the divided U.S. naval chain of command amplified problems in communication and coordination between Halsey and Kinkaid. This divided command was more important in determining the course of the battle than the tactical decision made by Halsey and led to an American disunity of effort that nearly allowed Kurita's mission to succeed."[19]

Losses

Due to the long duration and size of the battle, accounts vary as to the losses that occurred as a part of the Battle of Leyte Gulf and losses that occurred shortly before and shortly after. One account of the losses, by Samuel E. Morison, lists the following vessels:

Allied losses

The United States lost at least 12 warships during the Battle of Leyte Gulf:

- One light aircraft carrier: USS Princeton[94]

- Two escort carriers: USS Gambier Bay and USS St. Lo (the first major warship sunk by a kamikaze attack)[95]

- Two destroyers: USS Hoel and USS Johnston[95]

- Two destroyer escorts: USS Samuel B. Roberts and USS Eversole[96]

- One PT boat: USS PT-493

- Four other ships (including submarine USS Darter), along with HMAS Australia, were damaged.[97]

More than 1,600 sailors and aircrewmen of the Allied escort carrier units were killed. The losses in the Battle of Leyte Gulf were not evenly distributed throughout all forces. Very minimal Allied casualties occurred at the overwhelming Allied victories at the Battle of Surigao Strait and the Battle off Cape Engaño. At the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea the Japanese attack on the light aircraft carrier USS Princeton led to the loss of 108 killed on Princeton and 233 killed and 426 wounded on the light cruiser USS Birmingham due to secondary explosions on Princeton that caused severe damage on Birmingham. 123 troops were killed and over 150 were wounded in the first pre-planned kamikaze attacks of World War II on Taffy 1's aircraft carriers near Surigao Strait. At the mismatched Battle off Samar alone 5 of the 7 ships of the combined actions were lost along with 23 aircraft lost and 1,161 killed and missing and 913 wounded, comparable to the combined losses at the Battle of Midway and Battle of Coral Sea.[98] The destroyer Heermann, despite her unequal fight with the enemy, finished the battle with only six of her crew dead. As a result of communication errors and other failures, a large number of survivors from Taffy 3 were unable to be rescued for several days, and died unnecessarily as a consequence.[43][68] HMAS Australia suffered 30 officers and sailors dead, and another 62 servicemen wounded in a kamikaze-like attack 21 October 1944 at the start of the battle.[99] At the Battle of Surigao Strait 39 U.S. troops were killed, 114 were wounded and one PT boat (USS PT-493) was sunk.[100]

On 24–25 October, in two American submarine battles that were related to Japanese naval convoys involved in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, two U.S. submarines were lost in actions that led to the deaths of 1,938 U.S. troops. USS Tang (SS-306) sank numerous ships in a large Japanese convoy that was on the way to reinforce Japanese troops in Leyte and Leyte Gulf. Tang then accidentally sank herself in a circular run on the very last torpedo that she had in her arsenal. 78 men were killed while 9 survived and were captured by the Japanese. USS Shark (SS-314) sank the unmarked hell ship Arisan Maru, which was transporting American POWs from the Philippines to Formosa as a response to the Formosa Air Battle and the imminent invasion of the Philippines. 1,773 POWs died due to the rest of the Japanese convoy refusing to rescue them. This was the largest loss of life of U.S. troops at sea in history. Shark was sunk immediately by Japanese escort ships. All 87 crewmen on Shark died.[101]

Japanese losses

The Japanese lost 28 warships during the Battle of Leyte Gulf:[102]

- One fleet aircraft carrier: Zuikaku (flagship of the decoy Northern Forces and last of the original attacking Pearl Harbor carriers still afloat).

- Three light aircraft carriers: Zuihō, Chiyoda, and Chitose.

- Three battleships: Musashi (former flagship of the Japanese Combined Fleet), Yamashiro (flagship of the Southern Force) and Fusō.

- Six heavy cruisers: Atago (flagship of the Center Force), Maya, Suzuya, Chokai, Chikuma, and Mogami.

- Four light cruisers: Noshiro, Abukuma, Tama, and Kinu.

- Eleven destroyers: Nowaki, Hayashimo, Yamagumo, Asagumo, Michishio, Akizuki, Hatsuzuki, Wakaba, Uranami, Fujinami, and Shiranui.

Listed Japanese losses include only those ships sunk in the battle. After the nominal end of the battle, several damaged ships were faced with the option of either making their way to Singapore, close to Japan's oil supplies but where comprehensive repairs could not be undertaken, or making their way back to Japan, where there were better repair facilities but scant oil. The Nachi was lost to aerial attack while under repair at Manila Bay The cruiser Kumano and battleship Kongō were sunk retreating to Japan. Cruisers Takao and Myōkō were stranded, unrepairable, in Singapore. Many of the other survivors of the battle were bombed and sunk at anchor in Japan, unable to move without fuel.

Aftermath

The Battle of Leyte Gulf secured the beachheads of the U.S. Sixth Army on Leyte against attack from the sea. However, much hard fighting would be required before the island was completely in Allied hands at the end of December 1944: the Battle of Leyte on land was fought in parallel with an air and sea campaign in which the Japanese reinforced and resupplied their troops on Leyte while the Allies attempted to interdict them and establish air-sea superiority for a series of amphibious landings in Ormoc Bay—engagements collectively referred to as the Battle of Ormoc Bay.[103]

The Imperial Japanese Navy had suffered its greatest loss of ships and crew ever. Its failure to dislodge the Allied invaders from Leyte meant the inevitable loss of the Philippines, which in turn meant Japan would be all but cut off from its occupied territories in Southeast Asia. These territories provided resources that were vital to Japan, in particular the oil needed for her ships and aircraft. This problem was compounded because the shipyards and sources of manufactured goods, such as ammunition, were in Japan itself. Finally, the loss of Leyte opened the way for the invasion of the Ryukyu Islands in 1945.[11][104]

The major IJN surface ships returned to their bases to languish, entirely or almost entirely inactive, for the remainder of the war. The only major operation by these surface ships between the Battle for Leyte Gulf and the Japanese surrender was the suicidal sortie in April 1945 (part of Operation Ten-Go), in which the battleship Yamato and her escorts were destroyed by American carrier aircraft.

The first use of kamikaze aircraft took place following the Leyte landings. A kamikaze hit the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Australia on 21 October. Organized suicide attacks by the "Special Attack Force" (Japanese Special Attack Units) began on 25 October during the closing phase of the Battle off Samar, causing the destruction of the escort carrier St. Lo.

J. F. C. Fuller writes of the outcome of Leyte Gulf:[105]

The Japanese fleet had ceased to exist, and, except by land-based aircraft, their opponents had won undisputed command of the sea. When Admiral Ozawa was questioned on the battle after the war he replied: "After this battle the surface forces became strictly auxiliary, so that we relied on land forces, special [Kamikaze] attack, and air power ... There was no further use assigned to surface vessels, with the exception of some special ships." And "Admiral Mitsumasa Yoni, Navy Minister of the Koiso Cabinet, said he realized that the defeat at Leyte 'was tantamount to the loss of the Philippines.' As for the larger significance of the battle, he said, 'I felt that it was the end.'"

Memorials

- At the U.S. Naval Academy, in Alumni Hall, a concourse is dedicated to Lt. Lloyd Garnett and his shipmates on USS Samuel B. Roberts (DE-413), who earned their ship the reputation as the "destroyer escort that fought like a battleship" in the Battle of Leyte Gulf.

- The Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Leyte (CV-32) was named for the battle.

- The Ticonderoga-class cruiser USS Leyte Gulf (CG-55) is named for the battle.

- The Dealey-class destroyer escort USS Evans (DE-1023) was named in honor of Lt. Cmdr. Ernest E. Evans, commanding officer of the USS Johnston (DD-557).

- At Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego, California, several monuments are dedicated to Taffy 3 and the sailors lost during and after the Battle off Samar

- The Battle of Surigao Strait Memorial, in Surigao City overlooking the strait, was opened by city government and private partners on the 75th anniversary of the battle, October 25, 2019.[106]

See also

- United States Navy in World War II

- Imperial Japanese Navy of World War II

- Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

- Leyte-Samar Naval Base

- WWII carrier-versus-carrier engagements between Allied and Japanese naval forces:

References

Notes

- ↑ According to Army historian Robert Ross Smith, "Meeting with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in a conference at Pearl Harbor in late July 1944, ... MacArthur then argued persuasively that it was both necessary and proper to take Luzon before going on to Formosa, while Nimitz expounded a plan for striking straight across the western Pacific to Formosa bypassing Luzon. Apparently, no decisions on strategy were reached at the Pearl Harbor conferences. The Formosa versus Luzon debate continued without let-up at the highest planning levels for over two months, and even the question of bypassing the Philippines entirely in favor of a direct move on Formosa again came up for serious discussion."[16]

- ↑ CTF 38 claimed 655, including those shot down near the task force; the Japanese admitted 492, including an estimated '100 Army aircraft of all types.' ... the probability is that total enemy losses were somewhere between 550 and 600.[21]

- ↑ Fuller: "In the battle which ensued, the greatest up to then between ship- and shore-based aircraft, 650 Japanese aircraft were destroyed. As this meant the loss of most of Ozawa's half-trained aircrews, more than anything else it wrecked the Sho plan."[22]

- ↑ Kongō and Haruna were World War I-era battlecruisers that had received improved armour and boilers.

- ↑ Task Group 34.5 in fact only finished off the straggling destroyer Nowaki, and this was not achieved by the battleships, but rather by their accompanying cruisers and destroyers.[86][87]

Citations

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 415–429.

- ↑ Thomas 2006, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ Tillman, Barrett (October 2019). "The Navy's Aerial Arsenal at Leyte Gulf". Naval History Magazine. Vol. 33, no. 5. United States Naval Institute. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ↑ Thomas 2006, p. 322.

- ↑ Filipino: Labanan sa golpo ng Leyte, lit. 'Battle of Leyte gulf'

- ↑ Woodward 2007, pp. 1-3.

- ↑ "The Largest Naval Battles in Military History: A Closer Look at the Largest and Most Influential Naval Battles in World History". Military History. Norwich University. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 Thomas 2006.

- ↑ "Battle of Leyte Gulf". World War 2 Facts. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 101, 240–241, 300–303.

- 1 2 Fuller 1956a.

- ↑ Fuller 1956b, p. 600.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 360, 397.

- ↑ Fuller 1956b, p. 599, 600.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Smith 2000, p. 467.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 14–16.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 55–61.

- 1 2 Coleman 2006, p. iii.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 95.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Fuller 1956b, p. 601.

- ↑ Fuller 1956b, pp. 602–604.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 160–162.

- ↑ U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific) 1945, p. 317.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 169.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 160, 171.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 170; Hornfischer 2004, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 170–172.

- ↑ Nishida 2002.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 172; Cutler 1994, p. 100; Hornfischer 2004, p. 120.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 175, 184.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 177.

- ↑ BuShips 1947.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 178–183.

- ↑ DANFS Princeton.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 184–186.

- 1 2 Morison 1958, p. 186.

- ↑ L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Rear-Admiral Takeo Kurita". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- 1 2 Lee 1944.

- 1 2 Morison 1958.

- ↑ Cutler 1994, p. 110.

- 1 2 Cutler 1994, p. 111.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 291.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 290–291.

- ↑ Halsey 1952, p. 490.

- ↑ Woodward 2007, p. 76.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 196.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 240–241.

- 1 2 3 Sauer 1999.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 431.

- 1 2 Morison 1958, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 207–208, 212.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 215–217.

- ↑ Tully 2009, p. 275.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 224.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 224, 226, 241.

- ↑ Woodward 2007, p. 100.

- ↑ Holloway 2010.

- ↑ Bates 1958, p. 103.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 230–233.

- ↑ Cox, Samuel J. "H-038-2: The Battle of Leyte Gulf in Detail". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ↑ "Oral Histories – Battle of Leyte Gulf, 23–25 October 1945". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ↑ "USN Overseas Aircraft Loss List October 1944". aviationarchaeology.com. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 302–303, 366.

- 1 2 3 Hornfischer 2004.

- ↑ Woodward 2007, p. 164.

- ↑ Woodward 2007, pp. 173–174.

- ↑ AAIR 2007.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 302; Hornfischer 2004, pp. 352–354; AAIR 2007.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 424–428.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 318–330.

- ↑ Fuller 1956b, p. 614.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ Woodward 2007.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 295.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 292.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 329–330.

- ↑ Vego 2006, p. 284.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 330.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 331–332.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 334.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 330, 336.

- ↑ Cox 2019b.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 193.

- ↑ Rems 2017.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 194.

- 1 2 Cutler 1994.

- 1 2 Thomas 2006, p. 170.

- ↑ Kinkaid 1944.

- ↑ Morison 1958, p. 426.

- 1 2 Morison 1958, p. 421.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 420, 421.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 421, 422, 429.

- ↑ Cox 2019a.

- ↑ Cassells 2000, p. 24.

- ↑ Brown 2001; St. John 2004, p. 24.

- ↑ https://www.history.navy.mil/about-us/leadership/director/directors-corner/h-grams/h-gram-038.html Archived 26 September 2022 at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 26 September 2022

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 430–432.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 361–385.

- ↑ Morison 1958, pp. 397, 414.

- ↑ Fuller 1956b, p. 618.

- ↑ "Battle of Surigao Strait museum opens". Mindanao Gold Star Daily. 27 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

Bibliography

- Bates, R. W. (1958). Battle of Surigao Strait, October 24th–25th. The Battle for Leyte Gulf, October 1944: Strategical and Tactical Analysis. Vol. V. Washington, DC: U.S. Naval War College. p. 103.

- Brown, R. William (October 2001). "They Called Her 'Carole Baby'". Proceedings. U.S. Naval Institute. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Cassells, Vic (2000). The Capital Ships: Their Battles and their Badges. East Roseville, NSW: Simon & Schuster. p. 24. ISBN 0-7318-0941-6.

- Coleman, Kent S., LCDR, USN (16 June 2006). Halsey at Leyte Gulf: Command Decision and Disunity of Effort (PDF) (M.M.A.S. thesis). U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. p. iii. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2021 – via Defense Technical Information Center.

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cox, Samuel J. (11 October 2019a). "H-Gram H-036: Special Edition: No Higher Honor – The Battle off Samar, 25 October 1944". Director's Corner: H-Grams. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- Cox, Samuel J. (25 November 2019b). "H-Gram H-038-2: The Battle of Leyte Gulf in Detail". Director's Corner: H-Grams. Naval History and Heritage Command. Halsey's Response to Taffy 3's Plight. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Cutler, Thomas (1994). The Battle of Leyte Gulf: 23–26 October 1944. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-243-9.

- Evans, Mark L. (28 June 2019). "Princeton IV (CV-23)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- Fuller, J. F. C. (1956a). The Decisive Battles of the Western World. Vol. III. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 1-135-31790-9.

- Fuller, J. F. C. (1956b). A Military History of the Western World. Vol. III. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. LCCN 54-9733. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- Halsey, William F. (May 1952). "The Battle for Leyte Gulf". Proceedings. Vol. 78, no. 5. Annapolis, Maryland: U.S. Naval Institute. pp. 487–495. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- Holloway, James L. III (October 2010). "Second Salvo at Surigao Strait". Naval History Magazine. U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2004). The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors: The Extraordinary World War II Story of the U.S. Navy's Finest Hour. New York: Bantam. ISBN 0-553-80257-7. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- Kinkaid, Thomas C. (18 November 1944). Preliminary Action Report of Engagements in Leyte Gulf and off Samar Island on 25 October, 1944 (Report). Retrieved 17 January 2014 – via HyperWar Foundation.

- Lee, W. A. (14 December 1944). Report of Operations of Task Force Thirty-Four During the Period 6 October 1944 to 3 November 1944 (Report). Retrieved 10 July 2021 – via HyperWar Foundation.

- Morison, Samuel E. (1958). Leyte, June 1944 – January 1945. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. XII. Boston: Little & Brown. LCCN 47-1571. OCLC 1035611842. OL 24388559M. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- Naval Historical Center (29 May 2003). "Battle of Leyte Gulf, October 1944 – Loss of USS Princeton (CVL-23), 24 October 1944". Online Library of Selected Images: World War II in the Pacific. Department of the Navy. Retrieved 13 September 2021 – via HyperWar Foundation.

- Naval History and Heritage Command (n.d.). "USS Princeton (CVL-23)". Exhibits: Photography, U.S. Navy Ships. Retrieved 13 September 2021.

- "Navy and Marine Corps Awards Manual [Rev. 1953]; Memo – Changes". Naval History and Heritage Command. U.S. Navy. 19 August 1954. Enclosure (2): Ships at San Bernardino Strait on 24 and 26 October 1944, p. 1. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Nishida, Hiroshi (2002). "Imperial Japanese Navy". Archived from the original on 4 January 2013.

- Preliminary Design Section, Bureau of Ships (30 October 1947). U.S.S. Princeton (CVL23), Loss In Action; Battle for Leyte Gulf, 24 October 1944 (Report). Navy Department. War Damage Report No. 62. Retrieved 13 September 2021 – via Naval History and Heritage Command.

- Rems, Alan (October 2017). "Seven Decades of Debate". Naval History. Vol. 31, no. 5. Annapolis, Maryland: U.S. Naval Institute. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- Sauer, Howard (1999). The Last Big-Gun Naval Battle: The Battle of Surigao Strait. Glencannon Press. ISBN 1-889901-08-3.

- Smith, Robert Ross (2000) [1960]. "Chapter 21: Luzon Versus Formosa". Command Decisions. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-7. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 8 December 2007.

- St. John, Philip A. (2004) [1999]. USS Hancock CV/CVA-19: Fighting Hannah (2nd ed.). Turner Publishing Co. Retrieved 14 September 2021.