| Bodashtart | |

|---|---|

| Reign | c. 525 BC – c. 515 BC |

| Predecessor | Eshmunazar II |

| Successor | Yatonmilk |

| Phoenician language | 𐤁𐤃𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕 |

| Dynasty | Eshmunazar I dynasty |

| Religion | Canaanite polytheism |

.jpg.webp)

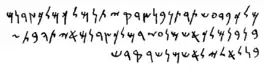

Bodashtart (also transliterated Bodʿaštort, meaning "from the hand of Astarte"; Phoenician: 𐤁𐤃𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕) was a Phoenician ruler, who reigned as King of Sidon (c. 525 – c. 515 BC), the grandson of King Eshmunazar I, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He succeeded his cousin Eshmunazar II to the throne of Sidon, and scholars believe that he was succeeded by his son and proclaimed heir Yatonmilk.

Bodashtart was a prolific builder, and his name is attested on some 30 eponymous inscriptions found at the Temple of Eshmun and elsewhere in the hinterland of the city of Sidon in Lebanon. The earliest discovered of Bodashtart's inscriptions was excavated in Sidon in 1858 and was donated to the Louvre. This inscription dates back to the first year of Bodashtart's accession to the throne of Sidon and commemorates the building of a temple to the goddess Astarte. The Temple of Eshmun podium inscriptions were discovered between 1900 and 1922 and are classified into two groups. The inscriptions of the first group, known as KAI 15, commemorate building activities in the temple and attribute the work to Bodashtart. The second group of inscriptions, known as KAI 16, were found on podium restoration blocks; they credit Bodashtart and his son Yatonmilk with the construction project and emphasise Yatonmilk's legitimacy as heir. The most recently discovered inscription as of 2020 was found in the 1970s on the bank of the Bostrenos River, not far from the Temple of Eshmun. The inscription credits the King with the building of water canals to supply the temple in the seventh year of his reign.

Three of Bodashtart's Eshmun temple inscriptions have been left in place; the others are housed in museums in Paris, Istanbul, and Beirut. Bodashtart is believed to have reigned for at least seven years, as evidenced by the Bostrenos River bank inscription. Little is known about his reign other than what has been learned from his dedicatory inscriptions.

Etymology

The name Bodashtart is the Romanized form of the Phoenician 𐤁𐤃𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕, meaning "from the hand of Astarte".[1] Spellings of the King's name include: Bdʿštrt,[2] Bad-ʿAštart,[3] Bodʿashtart,[4] Bodʿastart,[5] Bodaštart,[6] Bodʿaštort,[7] Bodachtart,[8] and Bodashtort.[9]

Chronology

The absolute chronology of the kings of Sidon from the dynasty of Eshmunazar I has been much discussed in the literature; traditionally placed in the course of the fifth century BC, inscriptions of this dynasty have been dated back to an earlier period on the basis of numismatic, historical, and archaeological evidence. A comprehensive examination of the dates of the reigns of these Sidonian kings has been presented by the French historian Josette Elayi who shifted away from the use of biblical chronology. Elayi used all the available documentation of the time and included inscribed Tyrian seals and stamps excavated by the Lebanese archaeologist Maurice Chehab in 1972 from Jal el-Bahr, a neighbourhood in the north of Tyre,[10][11][12][13][14] Phoenician inscriptions discovered by the French archaeologist Maurice Dunand in Sidon in 1965,[15] and the systematic study of Sidonian coins, which were the first dated coins in antiquity, bearing minting dates corresponding to the specific years of the reigns of the Sidonian kings.[11][16] Elayi placed the reigns of the descendants of Eshmunazar I between the middle and the end of the sixth century; according to her work, Bodashtart reigned from c.525 BC to c.515 BC.[17][18][19]

Historical context

Sidon, which was a flourishing and independent Phoenician city-state, came under Mesopotamian occupation in the ninth century BC. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC) conquered the Lebanon mountain range and its coastal cities, including Sidon.[20] In 705, King Luli joined forces with the Egyptians and Judah in an unsuccessful rebellion against Assyrian rule,[21][22] but was forced to flee to Kition with the arrival of the Assyrian army headed by Sennacherib. Sennacherib instated Ittobaal on the throne of Sidon and reimposed the annual tribute.[23] When Abdi-Milkutti ascended to Sidon's throne in 680 BC, he also rebelled against the Assyrians. In response, the Assyrian king Esarhaddon captured and beheaded Abdi-Milkutti in 677 BC after a three-year siege; Sidon was stripped of its territory, which was awarded to Baal I, the king of rival Tyre, and loyal vassal of Esarhaddon.[24]

Sidon returned to its former level of prosperity while Tyre was besieged for 13 years (586–573 BC) by the Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar II.[25] After the Achaemenid conquest in 539 BC, Phoenicia was divided into four vassal kingdoms: Sidon, Tyre, Byblos and Arwad.[26][27] Eshmunazar I, a priest of Astarte and the founder of his namesake dynasty, became King of Sidon around the time of the Achaemenid conquest of the Levant.[28] During the first phase of Achaemenid rule, Sidon flourished and reclaimed its former standing as Phoenicia's chief city, and the Sidonian kings began an extensive program of mass-scale construction projects, as attested in the Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II and Bodashtart inscriptions.[28][29][30]

Epigraphic sources

Bodashtart was a prolific builder who carved his eponymous inscriptions found at the Temple of Eshmun and elsewhere in the hinterland of the city of Sidon in Lebanon. The earliest discovered of the inscriptions, known today as CIS I 4, was found during excavations in Sidon in 1858. It was donated by French archaeologist Melchior de Vogüé to the Louvre where it is housed today.[31][32] The interpretation of inscription CIS I 4 is still a matter of debate; some scholars construe the text as a commemoration of building a temple to Astarte during the first year of Bodashtart's reign, while others posit that the text records the dedication of the Sharon plain to the temple of said goddess.[note 1][29][34][33] The Sidonian king carried out an extensive expansion and restoration project of the Temple of Eshmun, where he left some 30 dedicatory Phoenician inscriptions at the temple site that are divided into two groups belonging to two construction phases.[35][36] The first phase of the construction project involved adding a second podium at the base of the temple.[35] During this construction phase, a first group of inscriptions (known as KAI 15) were carved on the added podium's foundation stones. These inscriptions commemorate the construction project and attribute the work to Bodashtart alone.[29][37] The second set of inscriptions (KAI 16) was placed on ashlar restoration stones. The KAI 16 inscriptions mention Bodashtart and his son Yatonmilk, emphasize the latter's legitimacy as heir,[note 2][29][37] and assign him a share of credit for the construction project.[9][38][19] Yatonmilk is believed to have succeeded Bodashtart to the throne of Sidon as is inferred from the Bodashtart inscriptions. There is no further extant literary or archaeological evidence left by Yatonmilk himself.[39]

The KAI 15 and KAI 16 inscriptions were excavated from the Temple of Eshmun site between 1900 and 1922. Three of these inscriptions were left in situ while the rest were removed to the Louvre, the Istanbul Archaeology Museums, and the Archaeological Museum of the American University of Beirut.[40]

According to the American archaeologist and historian Charles Torrey and the Polish biblical scholar Józef Milik, the Bodashtart's KAI 15 inscriptions commemorate the building of the Eshmun temple and indicate the names of the quarters and territories of the Kingdom of Sidon.[note 3][7][41] Torrey interpreted the inscription thus: "The king, Bad-ʿAštart, king of the Sidonians, grandson of king ʾEšmunazar, king of the Sidonians; reigning in [or ruling over] Sidon-on-the-Sea, High-Heavens, [and] Rešep District, belonging to Sidon; who built this house like the eyrie of an eagle; (he) built it for his god Ešmun, the Holy Lord [Prince]."[3][42][note 4]

The KAI 16 Bodashtart inscriptions read: "King BDʿŠTRT and the legitimate (ṣdq) son, YTNMLK, King of the Sidonians, grandson of King Eshmunazor, King of the Sidonians, built this temple for the god ʾEšmun, the holy prince".[2][45][46] Another translation reads: "King Bodashtart, and his pious son (or legitimate successor), Yatonmilk, king of the Sidonians, descendants (bn bn) of King Eshmunazar, king of the Sidonians, this house he built to his god, to Eshmun, lord/god of the sanctuary".[47]

Another in situ inscription was recorded in the 1970s by Maurice Chéhab on the Bostrenos River bank 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) upstream from the Temple of Eshmun. The inscription credits Bodashtart with the building water installations to supply the temple and dates the work to the seventh year of his reign, which indicates that he ruled for at least this length of time.[note 5][29][49][50][12]

Apart from inscriptions detailing Bodashtart's building activity, little is known about his reign.[29]

Genealogy

Bodashtart was a descendant of Eshmunazar I's dynasty. Eshmunazar's heir was his son Tabnit, who fathered Eshmunazar II from his sister Amoashtart. Tabnit died before the birth of Eshmunazar II, and Amoashtart ruled in the interlude until the birth of her son, then was co-regent until he reached adulthood. Bodashtart was the nephew of Tabnit and Amoashtart and acceded to the throne after the death of Eshmunazar II at the young age of fourteen.[35][51][52] Some scholars misidentified Yatonmilk as the father of Bodashtart;[53] this was successfully contested by later epigraphists.[54][55][46]

| Eshmunazar I dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- King of Sidon – A list of the ancient rulers of the city of Sidon

Notes

- ↑ 1." Au mois de MP' dans l'année de son accession 2. à la royauté (lit. de son devenir roi), du roi Bod'ashtart 3. roi de Sidon, voici que le roi Bod'ashtart 4. roi de Sidon construisit ce SRN du pays 5. de la mer pour sa divinité Astarté ". In English: 1.'In the month of MP' in the year of his accession 2. to royalty (lit. of his becoming king), of King bod'ashtart 3. King of Sidon, behold, King bod'ashtart 4. King of Sidon built this SRN of the land 5. of the sea for his deity Astarte ".[33]

- ↑ Yatonmilk is referred to by Bodashtart as BN ṢDQ, meaning "true son" or "pious son".[35]

- ↑ mlk bdʿštrt mlk ṣdnm bn bn mlk ʾšmnʿzr mlk ṣdnm bṣdn ym šmm rmm ʾrṣ ršpm ṣdn mšl ʾš bn wṣdn šd ʾyt hbt z bn lʾly lʾšmn šd qdš Je traduirais ce texte difficile de la façon suivante; j'ajoute des explications entre parenthèses: "Le roi Bodʿaštort, roi des Sidoniens, petit-fils du roi Esmunʿazor, roi des Sidoniens, (qui règne, ou: qui habitent) dans la Sidon maritime (c.-à-d. dans la plaine côtière, avec ses zones ou quartiers du) Ciel-Haut, Terre-des-Rešafim, Sidon (de résidence, ou: de propriété) Royale, (les quartiers) qui en font partie, ainsi que dans la Sidon continentale (à savoir, dans le territoire de montagne, qui allait jusqu'à l' Anti-Liban et la vallée du Jourdain) – ce temple-ci, il (l') a construit à son dieu Eshmun du Territoire Saint".[7]

- ↑ Cf. : Eiselen 1907,[43] and Münnich 2013,[44] for other KAI 15 translations.

- ↑ "1. ... dans l’année sept de son règne (litt. de son être roi) le roi Bod'ashtart 2. roi de Sidon petit-fils du roi Eshmun‘azor roi de Sidon /(3a)qui avait construit/ dans Sidon de la Mer, 3. Cieux élevés, Pays des Resheps, en outre, à Sidon des Champs voici qu'il construisit et fit le roi Bod'ashtart roi de Sidon ce/le (?) ... " In english: "1. ... in year seven of his reign (litt. of his being king) King Bod'ashtart 2. King of Sidon grandson of King Eshmun'azor King of Sidon / (3a) who had built / in Sidon of the Sea, 3. High heavens, Land of the Resheps, moreover, in Sidon of the fields behold, he built and made the King bod'ashtart King of Sidon this / the (?) ... " [48]

References

- ↑ Gordon, Rendsburg & Winter 1987, p. 137.

- 1 2 Thomas 2014, p. 143.

- 1 2 Torrey 1902, p. 161.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2012, p. 12.

- ↑ Dupont-Sommer 1949, p. 126.

- ↑ Stucky 2002, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 Milik 1967, p. 575.

- ↑ Bordreuil 2002, p. 105.

- 1 2 Halpern 2016, p. 19.

- ↑ Kaoukabani 2005, p. 4.

- 1 2 Elayi 2006, p. 2.

- 1 2 Chéhab 1983, p. 171.

- ↑ Xella & López 2005b.

- ↑ Greenfield 1985, pp. 129–134.

- ↑ Dunand 1965, pp. 105–109.

- ↑ Elayi & Elayi 2004.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, pp. 22, 31.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2012, p. 6.

- 1 2 Elayi 2018a, p. 234.

- ↑ Bryce 2009, p. 651.

- ↑ Netanyahu 1964, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Yates 1942, p. 109.

- ↑ Elayi 2018b, p. 58.

- ↑ Bromiley 1979, pp. 501, 933–934.

- ↑ Aubet 2001, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ Boardman et al. 2000, p. 156.

- 1 2 Zamora 2016, p. 253.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Elayi 2006, p. 7.

- ↑ Pritchard & Fleming 2011, pp. 311–312.

- ↑ Vogüé 1860, p. 55.

- ↑ Zamora 2007, p. 100.

- 1 2 Amadasi Guzzo 2012, p. 9.

- ↑ Bonnet 1995, p. 215.

- 1 2 3 4 Elayi 2006, p. 5.

- ↑ Chabot & Clermont-Ganneau 1905, pp. 154–160.

- 1 2 Xella & López 2005a, p. 119.

- 1 2 Conteneau 1924, p. 16.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, pp. 5, 8.

- ↑ Bordreuil & Gubel 1990, pp. 493–499.

- ↑ Torrey 1937, p. 407.

- ↑ Teixidor 1969, p. 332.

- ↑ Eiselen 1907, p. 144.

- ↑ Münnich 2013, p. 240.

- ↑ Dussaud 1923, p. 149.

- 1 2 Xella & López 2005a, p. 121.

- ↑ Halpern 2016, p. 20.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2012, p. 11.

- ↑ Xella & López 2004, p. 294.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2012, pp. 6, 11.

- ↑ Lipiński 1995, pp. 135–451.

- ↑ Gibson 1982, p. 105.

- ↑ Bordreuil & Gubel 1990, p. 496.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, pp. 5, 7.

- ↑ Bonnet 1995, p. 216.

Bibliography

- Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia (2012). "Sidon et ses sanctuaires" [Sidon and its sanctuaries]. Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. 106: 5–18. doi:10.3917/assy.106.0005. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 42771737.

- Aubet, María Eugenia (2001). The Phoenicians and the West: Politics, Colonies and Trade (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521795432.

- Boardman, John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Lewis, David Malcolm; Ostwald, Martin (2000). The Cambridge Ancient History: Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean c.525 to 479 B.C. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521228046.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey (1979). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Q–Z. Vol. 4. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 9780802837844.

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste; Clermont-Ganneau, Charles, eds. (1905). Répertoire d'épigraphie sémitique [Semitic Epigraphy Directory]. Académie des Inscriptions & Belles-Lettres Commission du Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum (in French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

- Bonnet, Corinne (1995). "Phénicien šrn = Akkadien šurinnu – A propos de l'inscription de Bodashtart CIS I 4*" [Phoenician šrn = Akkadian šurinnu – A study of Bodashtart inscription CIS I 4*]. Orientalia (in French). Gregorian Biblical Press. 64 (3): 214–222. JSTOR 43078086.

- Bordreuil, Pierre; Gubel, Eric (1990). "Bulletin d'Antiquités Archéologiques du Levant Inédites ou Méconnues" [Bulletin of unpublished or unknown archaeological antiquities of the Levant]. Syria (in French). Institut Francais du Proche-Orient. 67 (2): 483–520. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4198843.

- Bordreuil, Pierre (2002). "À propos des temples dédiés à Echmoun par les rois Echmounazor et Bodachtart" [About temples dedicated to Echmoun by Kings Echmounazor and Bodachtart]. In Ciasca, Antonia; Amadasi, Maria Giulia; Liverani, Mario; Matthiae, Paolo (eds.). Da Pyrgi a Mozia : studi sull'archeologia del Mediterraneo in memoria di Antonia Ciasca [From Pyrgi to Mozia: studies on the archaeology of the Mediterranean in memory of Antonia Ciasca]. Vicino oriente (in French). Rome: Università degli studi di Roma "La sapienza". pp. 105–108.

- Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: From the Early Bronze Age to the Fall of the Persian Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415394857.

- Chéhab, Maurice (1983). "Découvertes phéniciennes au Liban" [Phoenician discoveries in Lebanon]. Atti del I congresso internazionale di studi Fenici e Punici [Proceedings of the first International Congress of Phoenician and Punic studies] (in French).

- Conteneau, Gaston (1924). "Deuxième mission archéologique à Sidon (1920)" [The second archaeological mission in Sidon (1920)]. Syria (in French). Institut Francais du Proche-Orient. 5 (1): 9–23. doi:10.3406/syria.1924.3094. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Dunand, Maurice (1965). "Nouvelles inscriptions phéniciennes du temple d'Echmoun, près Sidon" [New Phoenician inscriptions from the temple of Echmoun, near Sidon]. Bulletin du Musée de Beyrouth (in French). Ministère de la Culture – Direction Générale des Antiquités (Liban). 18: 105–109.

- Dupont-Sommer, André (1949). "Etude du texte phénicien des inscriptions de Karatepe (suite)" [Study of the Phoenician text of the inscriptions of Karatepe (continued)]. Oriens (in French). Brill. 2 (1): 121–126. doi:10.2307/1579407. ISSN 0078-6527. JSTOR 1579407.

- Dussaud, René (1923). "Les travaux et les découvertes archéologiques de Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1846–1923)" [The archaeological works and discoveries of Charles Clermont-Ganneau (1846–1923)]. Syria (in French). Institut Francais du Proche-Orient. 4 (2): 140–173. doi:10.3406/syria.1923.2984.

- Eiselen, Frederick Carl (1907). Sidon: A Study in Oriental History. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231928007.

- Elayi, Josette; Elayi, A. G. (2004). Le monnayage de la cité phénicienne de Sidon à l'époque perse (Ve-IVe s. av. J.-C.): Texte [The coinage of the Phoenician city of Sidon in the Persian era (V–IV s. av. J.-C.): Text] (in French). Paris: Gabalda. ISBN 9782850211584.

- Elayi, Josette (2006). "An updated chronology of the reigns of Phoenician kings during the Persian period (539–333 BCE)" (PDF). Digitorient. Collège de France – UMR7912. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 July 2020.

- Elayi, Josette (2018a). The History of Phoenicia. Atlanta, Georgia: Lockwood Press. ISBN 9781937040819.

- Elayi, Josette (2018b). Sennacherib, King of Assyria. Atlanta: SBL Press. ISBN 9780884143185.

- Gibson, John C. L. (1982). Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions. Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198131991.

- Gordon, Cyrus Herzl; Rendsburg, Gary; Winter, Nathan H. (1987). Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9780931464348.

- Greenfield, Jonas C. (1985). "A Group of Phoenician City Seals". Israel Exploration Journal. Israel Exploration Society. 35 (2/3): 129–134. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27925980.

- Halpern, Baruch (2016). "Annotations to royal Phoenician inscriptions from Persian Sidon, Zincirli (Kilamuwa), Karatepe (Azitawadda) and Pyrgi". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. Israel Exploration Society. 32: 18–27. ISSN 0071-108X. JSTOR 26732492.

- Kaoukabani, Ibrahim (2005). "Les estampilles phénicienne de Tyr" [The Phoenician stamps of Tyre] (PDF). Archaeology & History in the Lebanon (in French). AHL (21): 3–79.

- Lipiński, Edward (1995). Dieux et déesses de l'univers phénicien et punique [Gods and goddesses of the Phoenician and Punic universe] (in French). Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789068316902.

- Milik, Józef Tadeusz (1967). "Les papyrus araméens d'Hermoupolis et les cultes syro-phéniciens en Égypte perse" [The Aramaic papyri of Hermoupolis and the Syro-Phoenician cults in Persian Egypt]. Biblica (in French). Gregorian Biblical Press. 48 (4): 546–622. ISSN 0006-0887. JSTOR 42618436.

- Münnich, Maciej M. (2013). The God Resheph in the Ancient Near East. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161524912.

- Netanyahu, Benzion (1964). The World History of the Jewish People. Tel Aviv: Jewish History Publications Limited. ISBN 9780813506159.

- Pritchard, James B.; Fleming, Daniel E. (2011). The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691147260.

- Stucky, Rolf A. (2002). "Das Heiligtum des Ešmun bei Sidon in vorhellenistischer Zeit" [The sanctuary of Ešmun near Sidon in pre-Hellenistic times]. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (in German). Deutscher verein zur Erforschung Palästinas. 118 (1): 66–86. ISSN 0012-1169. JSTOR 27931685.

- Teixidor, Javier (1969). "Bulletin d'épigraphie sémitique: 1969" [Semitic Epigraphy Bulletin: 1969]. Syria (in French). Institut Francais du Proche-Orient. 46 (3/4): 319–358. doi:10.3406/syria.1969.6101. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4237190.

- Thomas, Benjamin D. (2014). Hezekiah and the compositional history of the Book of Kings. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161529351.

- Torrey, Charles C. (1902). "A Phoenician Royal Inscription". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 23: 156–173. doi:10.2307/592387. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 592387.

- Torrey, Charles C. (1937). "A New Phoenician Grammar". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 57 (4): 397–410. doi:10.2307/594519. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 594519.

- Xella, Paolo; López, José-Ángel Zamora (2005a). "L'inscription phénicienne de Bodashtart in situ à Bustān eš-Šēḫ (Sidon) et son apport à l'histoire du sanctuaire" [The in situ Phoenician inscription of Bodashtart in Bustān eš-Šēḫ (Sidon) and its contribution to the history of the sanctuary]. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (in French). Deutscher verein zur Erforschung Palästinas. 121 (2): 119–129. ISSN 0012-1169. JSTOR 27931768.

- Xella, Paolo; López, José-Ángel Zamora (2005b). "Nouveaux documents phéniciens du sanctuaire d'Eshmoun à Bustan esh-Sheikh (Sidon)" [New Phoenician documents from the sanctuary of Eshmun in Bustan esh-Sheikh (Sidon)]. In Arruda, A. M. (ed.). Atti del VI congresso internazionale di studi Fenici e Punici [Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of Phoenician and Punic studies] (in French). Lisbon: Gregorian Biblical Press. pp. 100–114.

- Xella, Paolo; López, José-Ángel Zamora (2004). "Une nouvelle inscription de Bodashtart, roi de Sidon, sur la rive du Nahr el-Awwāli, près de Bustān ēš-Šēḫ" [A new inscription by Bodashtart, King of Sidon, on the Bank of the Nahr El-Awwāli, near Bustān òš-Šēḫ]. BAAL (in French). Ministère de la Culture – Direction Générale des Antiquités (Liban). 8: 273–300.

- Vogüé, Melchior de (1860). "Mémoire sur une nouvelle inscription Phénicienne" [Memoir on a new Phoenician inscription]. Mémoires présentés par divers savants étrangers à l'Académie (in French). Institut de France. 6 (1): 55–73. doi:10.3406/mesav.1860.1032.

- Yates, Kyle Monroe (1942). Preaching from the Prophets. New York: Harper & brothers.

- Zamora, José-Ángel (2007). "The inscription from the first year of King Bodashtart of Sidon's reign: CIS I, 4". Orientalia. Gregorian Biblical Press. 76 (1): 100–113. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43077614.

- Zamora, José-Ángel (2016). "Autres rois, autre temple: la dynastie d'Eshmounazor et le sanctuaire extra-urbain de Eshmoun à Sidon" [Other kings, other temple: the dynasty of Eshmunazor and the extra-urban sanctuary of Eshmun in Sidon]. In Russo Tagliente, Alfonsina; Guarneri, Francesca (eds.). Santuari mediterranei tra Oriente e Occidente : interazioni e contatti culturali : atti del Convegno internazionale, Civitavecchia – Roma 2014 [Mediterranean sanctuaries between East and West: interactions and cultural contacts: Proceedings of the International Conference, Civitavecchia–Rome 2014] (PDF) (in French). Rome: Scienze e lettere. pp. 253–262. ISBN 9788866870975.