| Yatonmilk | |

|---|---|

| Reign | c. 515 BC – c. 486 BC |

| Predecessor | Bodashtart |

| Successor | Anysos |

| Burial | Unidentified |

| Phoenician language | 𐤉𐤕𐤍𐤌𐤋𐤊 |

| Dynasty | Eshmunazar I dynasty |

| Religion | Canaanite polytheism |

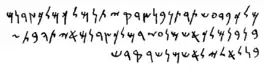

Yatonmilk (Phoenician: 𐤉𐤕𐤍𐤌𐤋𐤊, YTNMLK, Romanized also as Yatanmilk, Yaton Milk, Yatan-Milk) was a Phoenician King of Sidon (c. 515–486 BC), and a vassal to the Achaemenid king of kings Darius I.[2][3]

Etymology

The Romanized form Yatonmilk comes from the Phoenician 𐤉𐤕𐤍𐤌𐤋𐤊 (YTNMLK), meaning "the king gives" from 𐤉𐤕𐤍 (Yaton, "to give") and 𐤌𐤋𐤊 (Milk, "king").[4][5] Semitist and biblical scholar Marvin Pope posited that the epithet mlk may be an abbreviation of the name of the Phoenician god Melkart (melk-qart) which means "king of the city".[6]

Epigraphic sources

Yatonmilk's name was attested on many building stone-incised dedications dubbed the Bodashtart inscriptions that were found at the Temple of Eshmun in the hinterland of the city of Sidon in Lebanon. Despite being mentioned in the inscriptions, nothing is known about his reign due to the lack of further material or epigraphic evidence.[7][8]

Bodashtart, Yatonmilk's father who is dubbed the 'builder king', carried out an extensive expansion and restoration project of the Temple of Eshmun; he left more than thirty dedicatory inscriptions at the temple site.[9] The first phase of the works involved adding a second podium at the base of the temple.[9] During this construction phase inscriptions were carved on the added podium's foundation stones around 530 BC, these inscriptions, known as KAI 15, do not mention Yatonmilk.[10][11] A second set of inscriptions (KAI 16) were placed on restoration ashlar stones; these stones mention Yatonmilk and emphasize his legitimacy as heir, associate him with the reign of his father,[lower-alpha 1][10][11] and assign a share of credit to Yatonmilk for the construction project.[12] One example of the Bodashtart's inscriptions reads: "The king Bodashtart and his legitimate heir Yatonmilk, king of the Sidonians, grandson of king Eshmunazar, king of the Sidonians, built this temple to his god Eshmun, the Sacred Prince".[13] Another translation reads: "King Bodashtort, and his pious son (or legitimate successor), Yatonmilk, king of the Sidonians, descendants (bn bn) of King Eshmunazor, king of the Sidonians, this house he built to his god, to Eshmun, lord/god of the sanctuary."[14]

Some scholars misidentified Yatonmilk as the father of Bodashtart;[15] this was successfully contested by later epigraphists.[13][16][17]

Genealogy

Yatonmilk was a descendant of Eshmunazar I's dynasty. Eshmunazar's heir was his son Tabnit, who fathered Eshmunazar II from his sister Amoashtart. Tabnit died before the birth of Eshmunazar II, and Amoashtart ruled in the interlude until the birth of her son, then was co-regent until he reached adulthood. Bodashtart was the nephew of Tabnit and Amoashtart and acceded to the throne after the death of Eshmunazar II at the young age of fourteen.[9][18][19] Yatonmilk is the son of Bodashtart.[20][17][13]

| Eshmunazar I dynasty | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- King of Sidon – A list of the ancient rulers of the city of Sidon

Notes

References

- ↑ Conteneau 1924, p. 16.

- ↑ Leveque, Francis (2010-05-29). "Sidon au Ier millénaire av. J.-C". marine-antique.net (in French). Archived from the original on 2020-07-30. Retrieved 2020-07-30.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2015, p. 338.

- ↑ Benz 1972, p. 329.

- ↑ Pope 1955, p. 25–27.

- ↑ Elayi 2018, p. 234.

- ↑ Kelly 1987, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 Elayi 2006, p. 5.

- 1 2 Elayi 2006, p. 7.

- 1 2 Xella & López 2005, p. 119.

- ↑ Halpern 2016, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Xella & López 2005, p. 121.

- ↑ Halpern 2016, p. 20.

- ↑ Bordreuil & Gubel 1990, p. 496.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, p. 5,7.

- 1 2 Bonnet 1995, p. 216.

- ↑ Lipiński 1995, pp. 135–451.

- ↑ Gibson 1982, p. 105.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, pp. 5, 7.

Bibliography

- Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia (2015). "A. Les inscriptions phéniciennes". MOM Éditions. 67 (1): 335–345.

- Benz, Frank L. (1972). Personal Names in the Phoenician and Punic Inscriptions. Gregorian Biblical BookShop.

- Bonnet, Corinne (1995). "Phénicien šrn = Akkadien šurinnu – A propos de l'inscription de Bodashtart CIS I 4*". Orientalia (in French). Gregorian Biblical BookShop. 64: 216.

- Bordreuil, P.; Gubel, E. (1990). "Bulletin d'Antiquités Archéologiques du Levant Inédites ou Méconnues". Syria. 67 (2): 483–520. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4198843.

- Conteneau, Gaston (1924). "Deuxième mission archéologique à Sidon (1920)". Syria (in French). 5 (5–1): 9–23. doi:10.3406/syria.1924.3094. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- Elayi, Josette (2006). "An updated chronology of the reigns of phoenician kings during the Persian period (539-333 BCE)" (PDF). Digitorient. Collège de France – UMR7912 : Proche-Orient—Caucase : langues, archéologie, cultures.

- Elayi, Josette (2018-05-15). The History of Phoenicia. ISD LLC. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-937040-82-6.

- Gibson, John C. L. (1982). Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions. Vol. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198131991.

- Halpern, Baruch (2016). "Annotations to royal Phoenician inscriptions from Persian Sidon, Zincirli (Kilamuwa), Karatepe (Azitawadda) and Pyrgi – הארות על כתובות פיניקיות מצידון (מן התקופה הפרסית), מזינג'ירלי (כלמו), מקאראטפה (אזתוד) ומפירגי". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies / ארץ-ישראל: מחקרים בידיעת הארץ ועתיקותיה. לב: 18*–27*. ISSN 0071-108X. JSTOR 26732492.

- Kelly, Thomas (1987). "Herodotus and the Chronology of the Kings of Sidon". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (268): 39–56. doi:10.2307/1356993. ISSN 0003-097X. JSTOR 1356993. S2CID 163208310.

- Lipiński, Edward (1995). Dieux et déesses de l'univers phénicien et punique [Gods and goddesses of the Phoenician and Punic universe] (in French). Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789068316902.

- Pope, Marvin H. (1955). El in the Ugaritic texts. Brill Archive.

- Xella, Paolo; López, José-Ángel Zamora (2005). "L'inscription phénicienne de Bodashtart in situ à Bustān eš-Šēḫ (Sidon) et son apport à l'histoire du sanctuaire". Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins. 121 (2): 119–129. ISSN 0012-1169. JSTOR 27931768.

- Zamora, Jose Angel (2007). "The inscription from the first year of King Bodashtart of Sidon's reign: CIS I,4". Pontificium Institutum Biblicum. Retrieved 2011-01-30.