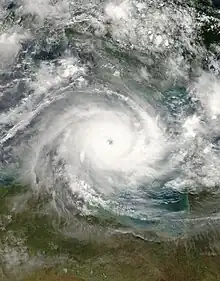

Monica prior to peak intensity on 23 April | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 16 April 2006 |

| Remnant low | 24 April 2006 |

| Dissipated | 28 April 2006 |

| Category 5 severe tropical cyclone | |

| 10-minute sustained (BOM) | |

| Highest winds | 250 km/h (155 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 916 hPa (mbar); 27.05 inHg |

| Category 5-equivalent tropical cyclone | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 285 km/h (180 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 879 hPa (mbar); 25.96 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | None |

| Damage | $5.1 million (2006 USD) |

| Areas affected | |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 2005–06 Australian region cyclone season | |

Severe Tropical Cyclone Monica was the most intense tropical cyclone, in terms of maximum sustained winds, on record to impact Australia. The 17th and final storm of the 2005–06 Australian region cyclone season, Monica originated from an area of low pressure off the coast of Papua New Guinea on 16 April 2006. The storm quickly developed into a Category 1 cyclone the next day, at which time it was given the name Monica. Travelling towards the west, the storm intensified into a severe tropical cyclone before making landfall in Far North Queensland, near Lockhart River, on 19 April 2006. After moving over land, convection associated with the storm quickly became disorganised.

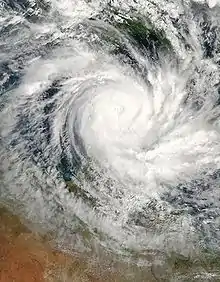

On 20 April 2006, Monica emerged into the Gulf of Carpentaria and began to re-intensify. Over the following few days, deep convection formed around a 37 km (23 mi) wide eye. Early on 22 April 2006, the Bureau of Meteorology (BoM) assessed Monica to have attained Category 5 status, on the Australian cyclone intensity scale. The Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) also upgraded Monica to a Category 5-equivalent cyclone, on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale. The storm attained its peak intensity the following day with winds of 250 km/h (160 mph) 10-minute winds) and a barometric pressure of 916 hPa (mbar; 27.05 inHg). On 24 April 2006, Monica made landfall about 35 km (22 mi) west of Maningrida, at the same intensity. Rapid weakening took place as the storm moved over land. Less than 24 hours after landfall, the storm had weakened to a tropical low. The remnants of the former-Category 5 cyclone persisted until 28 April 2006 over northern Australia.

In contrast to the extreme intensity of the cyclone, relatively little structural damage resulted from it. No injuries were reported to have occurred during the storm's existence and losses were estimated to be A$6.6 million (US$5.1 million). However, severe environmental damage took place. In the Northern Territory, an area about 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi) was defoliated by Monica's high wind gusts. In response to the large loss of forested area, it was stated that it would take several hundred years for the area to reflourish because of the large area it devasted.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Severe Tropical Cyclone Monica originated from an area of low pressure that formed early on 16 April 2006 off the coast of Papua New Guinea.[1] The low quickly became organised, with deep convection developing over the low-pressure centre. Later that day, the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert as the system became increasingly organised.[2] Early the next day, the Bureau of Meteorology in Brisbane, Australia declared that the low had developed into a Category 1 cyclone on the Australian tropical cyclone scale, with winds reaching 65 km/h (40 mph) 10-minute sustained).[3] Upon being classified as a cyclone, the storm was given the name Monica. At the same time, the JTWC designated Monica as Tropical Cyclone 23P.[4] Monica tracked generally westward, towards Far North Queensland, in response to a low to mid-level ridge to the south.[5]

Low wind shear and good divergence in the path of the storm allowed for continued intensification as continued westward.[6] Late on 17 April, Monica intensified into a category 2 cyclone, with winds reaching 95 km/h (59 mph) 10-minute sustained).[1][3] By 1200 UTC on 18 April, the Bureau of Meteorology upgraded Monica to a severe tropical cyclone, a Category 3 on the Australian scale.[3] This followed an increase in the storm's outflow and a fluctuating central dense overcast.[7] Several hours later, the JTWC upgraded Monica to the equivalent of a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale.[4] During the afternoon of 19 April, the storm made landfall roughly 40 km (25 mi) south-southeast of the Lockhart River with winds of 130 km/h (81 mph) 10-minute sustained).[1][3] At the same time, the JTWC assessed Monica to have intensified into a Category 2-equivalent storm with winds of 155 km/h (96 mph) 1-minute sustained).[4]

Shortly after making landfall, convection associated with the storm deteriorated and the outflow became fragmented. A shortwave trough to the south caused the ridge steering Monica to weaken, leading to the cyclone moving slower.[8] After moving over land, the storm began to weaken, with the Bureau of Meteorology downgrading the storm to weaken to Category 1 cyclone[3] and the JTWC downgraded the cyclone to a tropical storm.[4] The following day, Monica moved offshore, entering the Gulf of Carpentaria. Once back over water, favourable atmospheric conditions allowed the storm to quickly intensify.[1] Within 24-hours of moving over water, Monica re-attained severe tropical cyclone status.[3] Following a shift in steering currents, the storm slowed significantly and turned north-westward.[1][9] Steady intensification continued through 22 April as the storm remained in a region of low wind shear and favourable diffluence.[10] Early on 22 April the Bureau of Meteorology upgraded Monica to a Category 5 severe tropical cyclone, the third of the season.[1][3] By this time, a 37 km (23 mi) wide eye had developed within the central dense overcast of the cyclone.[11] Later that day, the JTWC assessed Monica to have intensified into a Category 5-equivalent storm.[4]

Cyclone Monica attained its peak intensity on 23 April near Cape Wessel with a barometric pressure 916 hPa (mbar; 27.05 inHg). Maximum winds were estimated at 250 km/h (160 mph) 10-minute sustained) by the Bureau of Meteorology[1][3] while the JTWC assessed it to have attained winds of 285 km/h (177 mph) 1-minute sustained).[4] Using the Dvorak technique, the peak intensity of the cyclone was estimated at T-number of 7.5 according to the Satellite Analysis Branch (SAB), yet the Advanced Dvorak Technique of the CIMSS automatically estimated at T8.0, the highest ranking on the Dvorak Scale.[12][13] However, since the JTWC, SAB and CIMSS are not the official warning centres for Australian cyclones, these intensities remain unofficial.[14]

On 24 April, the mid-level ridge south of Monica weakened, causing the storm to turn towards the southwest.[11] Following this, the storm made landfall in the Northern Territory, roughly 35 km (22 mi) west of Maningrida, as a Category 5 cyclone with winds of 250 km/h (160 mph) 10-minute sustained).[1] Soon after making landfall, the storm weakened extremely quickly. Most of the convective activity associated with the storm dissipated within nine hours of moving onshore. This resulted in the storm's maximum winds decreasing by 155 km/h (96 mph) in a 12-hour span.[3] After this rapid weakening, the storm turned sharply west moving over the town of Jabiru as a Category 2 cyclone. Within six hours of passing this town, the Bureau of Meteorology downgraded Monica to a tropical low, as the storm was no longer producing gale-force winds.[1] The JTWC issued their final advisory on the storm at 1800 UTC that day.[15] The remnants of Monica persisted for several more days, tracking near Darwin on 25 April before turning south-east and accelerating over the Northern Territory. The remnants eventually dissipated on 28 April over central Australia.[1]

Uncertainty in peak strength

The Bureau of Meteorology uses 10-minute sustained winds, while the Joint Typhoon Warning Center uses one-minute sustained winds.[16][17] The Bureau of Meteorology's peak intensity for Monica was 250 km/h (160 mph) 10-minute sustained, or 285 km/h (177 mph) one-minute sustained.[3][17] The JTWC's peak intensity for Monica was 285 km/h (177 mph) one-minute sustained, or 250 km/h (160 mph) 10-minute sustained.[4][17]

While the storm was active the Bureau of Meteorology's Darwin Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre estimated that Monica, had peaked with a minimum pressure of 905 hPa (26.72 inHg).[18][19] However, during their post analysis of Monica, the Darwin Tropical Cyclone Warning Centre estimated using the Love-Murphy pressure-wind relationship, that the system had a minimum pressure of 916 hPa (27.05 inHg).[19][20] However, since then the BoM has started to use the Knaff, Zehr and Courtney pressure-wind relationship, which has estimated that Monica had a minimum pressure of 905 hPa (26.72 inHg).[20] Other pressure estimates include the Joint Typhoon Warning Center's post analysis estimated pressure of 879 hPa (25.96 inHg) and the University of Wisconsin-Madison's Advanced Dvorak Technique which estimated a minimum pressure of 868.5 hPa (25.65 inHg).[4][13][21] The Advanced Dvorak Technique pressure estimate would suggest that the system was the most intense tropical cyclone ever recorded worldwide as the pressure is below that of the current world record holder, Typhoon Tip of 1979.[19] In 2010, Stephen Durden of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory studied Cyclone Monica's minimum pressure and suggested that the system likely peaked between 900–920 hPa (26.58–27.17 inHg) and strongly refuted claims that Monica was the strongest tropical cyclone on record.[19]

Preparations and impact

Queensland

Upon being declared as Tropical Cyclone Monica on 17 April, the Bureau of Meteorology issued a gale warning for areas along the eastern coast of Far North Queensland and for northen new south wales.[5] Several hours later, a cyclone warning was issued for north-eastern areas as the storm intensified.[22] An estimated 1,000 people were planned to be evacuated in Far North Queensland before officials shut down major highways in the area. Ferry services in the Great Barrier Reef and flights in and out of the region were cancelled.[23] However, no evacuations took place according to the Emergency Management in Australia.[24] An aborigine community of 700, located around the mouth of the Lockhart River, were in the direct path of the storm. The chief executive officer of the community stated that they were ready for the storm, having suffered no losses from Cyclone Ingrid which impacted the same area in 2005.[25]

Little damage was recorded in Queensland, despite Cyclone Monica being a Category 3 cyclone, as the storm impacted a sparsely populated region of the Cape York peninsula.[24] A storm surge of 1.23 m (4.0 ft) was recorded in Mossman and waves were recorded up to 4.24 m (13.9 ft) in Weipa.[26] Heavy rainfall was also associated with the storm, exceeding 400 mm (16 in) near where Monica made landfall. Wind gusts up to 109 km/h (68 mph) were recorded as the storm traversed the peninsula.[1] Officials reported about 15 percent of the structures along the Lockhart River sustained minor damage.[24] Minor coastal flooding was also reported due to Monica.[26] Three Torres Strait Islanders were rescued after 22 days drifting at sea in the wake of the cyclone passing through the Torres Strait, north of mainland Queensland.[27]

Northern Territory

Officials closed schools throughout the region in advance of the storm on 24 April and advised people to evacuate. A 10 pm curfew was also put in place to keep people off the streets during the night.[28] Local tours in the territory were postponed or cancelled due to the storm. Several flights in and out of Darwin were also cancelled, as was the Darwin Anzac Day march.[29][30] Alcan, the world's second-largest aluminium producer, warned customers of potential interruptions to supplies on contracts from its Gove refinery.[31] Rio Tinto's Ranger Uranium Mine ceased operations on 24 April, "as a precautionary measure".[32]

At one point, Monica was forecast to pass directly over Goulburn Island. In response, officials evacuated the island's 337 residents to shelters set up in Pine Creek. Numerous schools in the threatened region, especially in Darwin, were closed ahead of Monica's arrival.[33] Several shelters were opened in Darwin early on 24 April in anticipation of an influx of evacuees. Stores throughout the area reported increased sales for storm supplies, with some reducing prices on specific items.[34] The same day, the Darwin Returned and Services League of Australia cancelled all ANZAC Day services and marches in Darwin that were to be held the next day, to ensure the safety of prospective participants.[35]

The Wessel Islands, located off the coast of the region, suffered significant damage from the storm. Mangrove trees were uprooted throughout the islands and sand dunes were destroyed. An outstation located on one of the islands was destroyed by the cyclone.[36] The highest 24-hour rainfall from the storm was recorded near Darwin at 340 mm (13 in).[1] A storm total for the same area was recorded at 383 mm (15.1 in), surpassing the rainfall record for the entire month of April set in 1953.[37] Although the storm made landfall at peak intensity in Australia's Northern Territory, the impacted areas were sparsely populated. Around the region where Monica made landfall, evidence of a 5–6 m (16–20 ft) storm surge was present in Junction Bay.[24]

Wind gusts up to 148 km/h (92 mph) felled power lines in Maningrida;[38] 12 homes sustained damage from fallen trees in Jabiru; and extensive damage was reported in Gunbalanya (formerly known as Oenpelli).[39] Roughly 1,000 people also lost phone service in the region.[33] Several highways were blocked by fallen trees throughout the area.[24] A resort in Jabiru sustained significant damage and was closed for two weeks following the storm.[29] Insured damages to the national parks amounted to A$1.6 million (US$766,000).[40] According to the Northern Territory Insurance Office, structural damage from Cyclone Monica amounted to A$5 million (US$4.4 million).[41]

The remnants of Monica produced significant rainfall over parts of the Northern Territory several days after the system weakened below cyclone status. Flash flooding was reported throughout the Adelaide River basin as up to 261 mm (10.3 in) of rain fell in a 24-hour span.[1] On 26 April, the remnants of Monica spawned a small tornado near Channel Point; several mangrove trees were snapped and branches were thrown to nearby beaches.[42]

Environmental impacts

The full-force of Monica's estimated 360 km/h (220 mph) wind gusts were felt in the unpopulated tropical savanna regions of northern Australia. A large-scale windthrow event affected approximately 10,400 km2 (4,000 sq mi) of forest, resulting in the damage or destruction of 140 million trees. Damage extended 60–70 km (37–43 mi) north and south of Monica's centre and progressed 200 km (120 mi) inland. The affected areas primarily consist of Eucalyptus (namely E. miniata and E. tetrodonta) and Corymbia (namely C. dichromophloia, C. latifolia, and C. foelscheana) tree species. Common grasses in the savanna area include Triodia bitextura and Sorghum. Areas near the cyclone's landfall point—Junction Bay—also comprise wetlands and Melaleuca swamp forests. The heaviest damage occurred just east of the landfall point, with more than 85 percent of vegetation severely damaged; it spanned 139 km2 (54 sq mi).[43] In this area, trees were completely defoliated, snapped, and/or uprooted. Within 22 km (14 mi) of Junction Bay, 77 percent of all trees were uprooted or snapped at the trunk, while 84 percent suffered total defoliation. In the Melaleuca swamps, 60 percent of trees were snapped or uprooted once wind gusts exceeded 144 km/h (89 mph).[38] Approximately 12.7 million tonnes of vegetative debris was created by the storm.[43]

The Goomadeer River catchment, which flows into Junction Bay, was entirely denuded. The prolific loss of trees led to hydrologic changes in the region, with flood events likely becoming more severe as groundwater flow increased.[38] Farther southwest, the Magela Creek catchment in Kakadu National Park suffered a direct hit from the weakening cyclone. Gusts up to 135 km/h (84 mph) impacted the Ngarradj sub-catchment, destroying 42 percent of the tree canopy cover. Long-term losses in the sub-catchment reached 23 percent. Less rainfall than would normally be expected with such a storm lessened tree loss in the area, with soils largely not becoming saturated enough to allow trees to topple over.[44] The large amount of debris left behind contained approximately 51–60 million tonnes of greenhouse gases—primarily carbon dioxide—or roughly 10 percent of Australia's annual anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.[43][38] With Monica occurring just before the onset of the dry season, widespread brushfires were anticipated in the affected regions owing to the large amount of kindling. However, analysis of satellite imagery revealed only slightly above-average fire activity in the months following the cyclone.[43]

Recovery

Within weeks of the storm, the Alligator Rivers Region Advisory Committee began planting seedlings in deforested areas. By August 2006, a review of the growth of the new plants found that 81% to 88% of the seeds had survived and begun growing. To fully restore the South Alligator valley, environmentalists requested A$7.4 million (US$6.6 million) in funds.[45] In a study at Magela Creek a year after the storm, it was determined that between 8% and 19% of the tree canopy lost due to the storm had begun to recover.[44] Additional studies at the Gulungul Creek and the Alligator Rivers region revealed that suspended sediment values in flowing water had temporarily increased in the wake of Monica. The above-average values persisted for roughly a year before the streams returned to pre-cyclone sediment levels.[46] In a study of the Arnhem forests which were devastated by the cyclone, environmentalists reported that it would take over 100 years for the forest to recover. The storm's winds snapped numerous trees, estimated to have been over 200 years old and more than 60 cm (23.5 in) in diameter. It is estimated that it would take several hundred years before trees of similar sizes would flourish in the region.[47]

Aftermath

The Queensland Government State Disaster Management Group dispatched relief helicopters to remote communities for evacuation of people in flood zones and transport of relief workers.[24] Relief efforts were already underway in relation to Cyclone Larry which caused significant damage in Queensland. The Government of Australia assisted affected business by providing disaster loans up to A$25,000 for severely impacted areas and A$10,000 for less affected areas. Farmers were also provided with up to $200,000 in loans over a period of nine years.[48] Following the impacts in the Northern Territory, two cleanup teams were dispatched from Darwin to assist in cleanup efforts in the hardest hit regions.[24] Despite the minimal damage caused by Monica, the name was retired from the circulating lists of tropical cyclone names for the Australian Region.[49]

See also

- List of the most intense tropical cyclones

- Cyclone Winston – The most intense tropical cyclone in the Southern Hemisphere on record

- Cyclone Pam – One of the strongest cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere

- Cyclone Marcus - Would later tie with Monica for the strongest reported maximum sustained winds.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Severe Tropical Cyclone Monica: Northern Territory Regional Office". Australian Government. Bureau Of Meteorology. 29 April 2006. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (16 April 2006). "Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert". Unisys Weather. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Australian Region Tropical Cyclone Best Tracks". Bureau of Meteorology. 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Cyclone 23S Best Track". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 March 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- 1 2 Joint Typhoon Warning Center (17 April 2006). "Tropical Cyclone 23P Warning 001". Unisys Weather. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (17 April 2009). "Tropical Cyclone 23P". Unisys Weather. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ "High Seas Warning". Bureau of Meteorology. Unisys Weather. 18 April 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (19 April 2006). "Cyclone 23P Warning 006". Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (21 April 2006). "Cyclone 23P Advisory 009". Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (21 April 2006). "Cyclone 23P Advisory 010". Unisys Weather. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- 1 2 Gary Padgett (6 August 2006). "Monthly Tropical Weather Summary for April 2006". Australia Severe Weather. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Satellite Analysis Branch. "Advisories on 23 April 2006" (TXT). Mtarchive Data Server. Iowa State University of Science and Technology. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Advanced Dvorak Technique Intensity listing for Tropical Cyclone 23P (Monica)". Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies. 2006. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Chris Landsea (2010). "What regions around the globe have tropical cyclones and who is responsible for forecasting there?". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (24 April 2006). "Cyclone 23P Advisory 017 (Final)". Unisys Weather. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 2005. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Section 2 Intensity Observation and Forecast Errors". United States Navy. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 August 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ "Significant Weather Summary: April 2006" (PDF). Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Stephen L. Durden (12 July 2010). "Remote Sensing and Modeling of Cyclone Monica near Peak Intensity". Atmosphere. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. 1 (1): 15–33. Bibcode:2010Atmos...1...15D. doi:10.3390/atmos1010015. ISSN 2073-4433.

- 1 2 Joe Courtney; John A Knaff (2009). "Adapting the Knaff and Zehr wind-pressure relationship for operational use in Tropical Cyclone Warning Centres" (PDF). Australian Meteorological and Oceanographic Journal. Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 58 (3): 167–179. doi:10.22499/2.5803.002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2003). "Cyclone 06P Best Track". Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2010.

- ↑ "High Seas Warning". Bureau of Meteorology. Unisys Weather. 17 April 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ "Monica threatens Cairns with floods". The Age. Melbourne. Australian Associated Press. 19 April 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Tropical Cyclone Monica". Emergency Management Australia. 16 September 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ "Cyclone Monica makes landfall in Australia; no reports of injuries or damage". USA Today. Associated Press. 19 April 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- 1 2 "Tropical Cyclone Monica". Emergency Management Australia. 18 May 2006.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ "Torres Strait sea rescue an 'act of God'". The Age. Melbourne. 10 May 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (24 April 2006). "Island communities brace for Monica". ABC News. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- 1 2 Staff Writer (26 April 2006). "Sigh of relief as Cyclone Monica leaves minimal damage". Travel Weekly.

- ↑ "Darwin Battens Down for Monica Hell Storm Targets City". The Cairns Post. 25 April 2006. p. 5.

- ↑ Macdonald-Smith, Angela (23 April 2006). "Tropical cyclone Monica threatens Australia's northern coast". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ "Australia Braces For Major Cyclone". CBS News. Associated Press. 24 April 2006. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- 1 2 Staff Writer (25 April 2006). "Goulburn Island residents heading home after cyclone Monica". ABC Australia. Archived from the original on 12 August 2007. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (24 April 2006). "Darwin braces for cyclone Monica". ABC Australia. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Jano Gibson and Dylan Welch (24 April 2006). "Warning: Monica's a monster". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (6 July 2006). "Study finds islands suffered brunt of Cyclone Monica". ABC News. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ National Climatic Data Center (2006). "Global Hazards: April 2006". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Garry D. Cook and Clemence M. A. C. Goyens (6 May 2008). "The impact of wind on trees in Australian tropical savannas: lessons from Cyclone Monica". Austral Ecology. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation. 33 (4): 462–470. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2008.01901.x.

- ↑ "Business: Parliamentary Record (Hansard) and Minutes of Proceedings". Legislative Assembly of the Northern Territory. 9 August 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ↑ "Financial and Commonwealth reserves system summaries" (PDF). Government of Australia. 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (17 May 2006). "Cyclone Monica insurance claims hit $5m". ABC News. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Staff Writer (May 2006). "Significant Weather — April 2006" (PDF). Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 L. B. Hutley, B. J. Evans, J. Beringer, G. D. Cook, S. W. Maier, and E. Razon (13 November 2013). "Impacts of an extreme cyclone event on landscape-scale savanna fire, productivity and greenhouse gas emissions". Environmental Research Letters. IOP Publishing. 8 (4): 045023. Bibcode:2013ERL.....8d5023H. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/4/045023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- 1 2 Grant W. Staben and Kenneth G. Evans (6 May 2008). "Estimates of tree canopy loss as a result of Cyclone Monica, in the Magela Creek catchment northern Australia". Austral Ecology. 33 (4): 562–569. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2008.01911.x. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ↑ Various Writers (22 August 2006). "August 2006 Alligator Rivers Region Advisory Committee Meeting Summary" (PDF). Alligator Rivers Region Advisory Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Various Writers (2010). "ERISS Research Summary 2008-2009" (PDF). Environmental Research Institute of the Supervising Scientist. Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ↑ Kate Sieper (25 June 2006). "A 100-year wait to see the Arnhem forests again". ABC News. Retrieved 25 March 2009.

- ↑ Staff Writer (26 May 2006). "Tropical Cyclone Monica". Government of Australia.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ Staff Writer (2009). "Tropical Cyclone Names". Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

External links

- BoM Report of Severe Tropical Cyclone Monica

- BoM Best Track Data of Severe Tropical Cyclone Monica from IBTrACS

- JTWC Best Track Data Archived 1 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine of Tropical Cyclone 23P (Monica)

- 23P.MONICA Archived 27 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory