The tomb of Tutankhamun was discovered in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 by excavators led by the Egyptologist Howard Carter, more than 3,300 years after his death and burial. Whereas the tombs of most pharaohs were plundered by graverobbers in ancient times, Tutankhamun's tomb was hidden by debris for most of its existence and therefore not extensively robbed. It thus became the first known largely intact royal burial from ancient Egypt.

The tomb was opened beginning on 4 November 1922 during an excavation by Carter and his aristocratic patron, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon. The unexpectedly rich burial consisted of more than five thousand objects, many of which were in a highly fragile state, so conserving the burial goods for removal from the tomb required an unprecedented effort. The opulence of the burial goods inspired a media frenzy and popularised ancient Egyptian-inspired designs with the Western public. To the Egyptians, who had recently become partially independent of British rule, the tomb became a symbol of national pride, strengthening Pharaonism, a nationalist ideology that emphasised modern Egypt's ties to the ancient civilisation, and creating friction between Egyptians and the British-led excavation team. The publicity surrounding the excavation intensified when Carnarvon died of an infection, giving rise to speculation that his death and other misfortunes connected with the tomb were the result of an ancient curse.

After Lord Carnarvon's death, tensions arose between Carter and the Egyptian government over who should control access to the tomb. In early 1924, Carter stopped work in protest, beginning a dispute that lasted until the end of the year. Under the agreement that resolved the dispute, the artefacts from the tomb would not be divided between the government and the dig's sponsors, as was standard practice in previous Egyptological digs, and most of the tomb's contents went to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. In later seasons media attention waned, apart from coverage of the removal of Tutankhamun's mummy from its coffin in 1925. The last two chambers of the tomb were cleared from 1926 to 1930, and the last of the burial goods were conserved and shipped to Cairo in 1932.

The tomb's discovery did not reveal as much about the history of Tutankhamun's time as Egyptologists had initially hoped, but it did establish the length of his reign and gave clues about the end of the Amarna Period, the era of radical innovation that preceded his reign. It was more informative about the material culture of Tutankhamun's time, demonstrating what a complete royal burial was like and providing evidence about the lifestyles of wealthy Egyptians and the behaviour of ancient tomb robbers. The interest generated by the find stimulated efforts to train Egyptians in Egyptology. Since the discovery, the Egyptian government has capitalised on its enduring fame by using exhibitions of the burial goods for purposes of fundraising and diplomacy, and Tutankhamun has become a symbol of ancient Egypt itself.

Background

Burial and ancient robberies

The pharaoh Tutankhamun ruled during the Eighteenth Dynasty, during the New Kingdom. He died c. 1323 BC and was entombed in the Valley of the Kings, near Thebes (modern Luxor), like most New Kingdom rulers.[1] Instead of a full-size royal tomb cut into the slopes of the valley, he was interred in a small tomb dug into the valley floor, probably a private tomb that was modified to fit the large amount of goods that accompanied a royal burial.[2]

The tomb was robbed twice soon after its construction. Officials restored and resealed it, filling the entrance passage with chips of limestone to deter further intrusion. During the reigns of Ramesses V and Ramesses VI, nearly two centuries after Tutankhamun's death, his tomb was covered by debris from the construction of their tomb, KV9.[Note 1] Tutankhamun's tomb was thus hidden from later waves of robbery so that, unlike the other tombs in the valley, it retained most of the goods it was stocked with.[5]

Exploration of the Valley of the Kings

In the early twentieth century Egypt was a de facto British colony, ostensibly ruled by monarchs from the Muhammad Ali dynasty but in fact managed by a British consul-general, who oversaw a government staffed by Egyptians but dominated by the British. Egyptology, the study of ancient Egypt, was overseen by the Antiquities Service, a department of the Egyptian government.[6][7] New excavations of ancient sites were heavily dependent on the system known as "partage" or "division of finds": museums or private collectors of ancient artefacts would fund an Egyptological dig in exchange for a share of the artefacts, customarily half, and the remainder went to the Antiquities Service and its museum, the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.[8][9]

Many of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings had been open since ancient times.[10] Dozens of others, whose entrances had been deliberately buried by their builders or had become hidden by flash flood debris, were discovered in the course of the nineteenth century.[11][12] Royal mummies[13] and individual burial goods were discovered in some of these tombs, but nothing close to a complete set of royal burial equipment was found.[14]

A period of rapid discoveries in the valley began after Howard Carter became the Antiquities Service's inspector for Upper Egypt, including the Valley of the Kings, in 1900.[15] Carter had come to Egypt as an artist, assisting in recording Egyptian tomb art, and was then trained as an archaeologist.[16] As inspector, Carter both restored and protected the open tombs in the valley and sought to dig for undiscovered tombs. In searching for a patron to fund these efforts he found Theodore M. Davis, a wealthy American who regularly visited Egypt. With Davis's support Carter made several small finds and cleared three previously unexplored tombs.[17] After the Antiquities Service transferred Carter to Lower Egypt in 1904, Davis held the concession to excavate in the valley for another ten years, his efforts managed by a series of five archaeologists.[15] Davis pressured these excavators to work rapidly,[18] nearly doubling the number of known tombs in the valley,[19] but his discoveries were often carelessly treated and inadequately documented.[20] His excavation of KV55, the tomb of a member of the royal family from Tutankhamun's time, was so poorly handled that the identity of its occupant has been uncertain ever since.[21]

Little was known about Tutankhamun in Davis's time, though he was known to have restored traditional practices in the monarchy after a brief episode of radical innovation known as the Amarna Period. It was thus likely that he was buried in the Valley of the Kings, the traditional site for royal burials before and after the Amarna Period.[22] Davis never found Tutankhamun's tomb, assuming no tomb would have been cut into the valley floor, but he did find signs that the king had been buried in the valley.[23] One such sign was a pit, discovered in 1907 and designated KV54, that contained a handful of objects bearing Tutankhamun's name. These objects are now thought to have been either burial goods that were originally stored in the entrance corridor of Tutankhamun's tomb, which were removed and reburied in KV54 when the restorers filled the corridor, or objects related to Tutankhamun's funeral. Another was an uninscribed tomb, found in 1909 and known as KV58, that contained pieces of a chariot harness bearing Tutankhamun's name and that of his successor, Ay. Davis concluded that KV58 was all that remained of Tutankhamun's burial, which would mean that virtually all the kings' tombs expected to exist in the valley were accounted for.[24] The last years of Davis's work in the valley produced almost no finds, and in 1912 he wrote: "I fear the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted."[25]

Scouring the valley

Carter left the Antiquities Service in 1905 after a group of French tourists forced their way into a closed archaeological site at Saqqara and he ordered the Egyptian guards to eject them. The use of force by Egyptians against Europeans caused a scandal and led to his resignation.[26] He subsequently worked as an excavator for George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon, a collector of Egyptian antiquities, at several sites in Egypt. Carnarvon bought the concession for the Valley of the Kings when Davis relinquished it in 1914, and although the First World War made it difficult to conduct fieldwork, in 1917 Carter began to clear the valley down to the bedrock.[27] This required sifting through the spoil heaps produced by decades of earlier excavations, as well as the valley's natural alluvium.[28] At the time neither Carter nor Carnarvon stated they were looking for Tutankhamun's tomb, but there was reason for them to believe it had not been found. The objects in KV54 and KV58 indicated that Tutankhamun had been buried somewhere in the valley, but such meagre remains were unlikely to be a royal burial.[29]

During these excavations the political status of Egypt changed dramatically. The Egyptian Revolution of 1919 convinced British authorities that Egypt's current status was unsustainable, and they issued the Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence in February 1922. It left the United Kingdom with substantial influence over the government, particularly in military and foreign affairs.[30] Antiquities policy was one of the areas ceded to the Egyptians. The Antiquities Service retained its incumbent director, Pierre Lacau, but he now answered to an Egyptian minister of public works.[31]

The season for excavation and tourism in Egypt extends from November to April, avoiding the worst of the country's heat.[32] In mid-1922, when Carter and Carnarvon were paused between digging seasons, only one section of the Valley of the Kings remained covered by debris. This area was difficult to clear because it included the remains of ancient workers' huts and lay close to the entrance to KV9, which attracted heavy tourist traffic. Carnarvon discussed abandoning excavation in the valley, given how fruitless the effort had been, but Carter offered to cover the expense of clearing this final section. Carnarvon, impressed by Carter's dedication, agreed to fund the work for one more season.[33]

Discovery and clearance

First season

Discovery

To minimise the disruption to tourists, Carter and his Egyptian workforce began on 1 November 1922, earlier in the season than usual.[34] On 4 November a worker uncovered a step in the rock. According to Carter's published account the workmen discovered the step while digging beneath the remains of the huts; other accounts attribute the discovery to a boy digging outside the assigned work area.[35][Note 2] The step proved to be the beginning of a tomb entrance staircase. At the bottom stood a doorway sealed with limestone and plaster, into which Carter cut a peephole to see the passage beyond was filled with rubble.[39][40] Carter sent a telegram to Carnarvon, then in England, and had the workmen re-fill the pit to secure the tomb until Carnarvon's arrival. While waiting, Carter asked his friend and colleague Arthur Callender to assist with the upcoming excavation.[41]

The digging resumed after 23 November with Carnarvon's arrival in Luxor with his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert. Upon closer examination the doorway seal was found to be inscribed with the name of Tutankhamun, suggesting that this was his tomb. The debris that filled the passage contained objects bearing the names of other kings, suggesting it might be a cache of miscellaneous objects buried during his reign. The doorway had been partially demolished before being resealed, indicating an ancient robbery. On 26 November the excavators reached another sealed doorway.[42] Carter's book on the discovery, co-written with Arthur Cruttenden Mace, described the breaching of the seal in one of the most famous passages in the history of archaeology:[43][44]

With trembling hands I made a tiny breach in the upper left-hand corner. Darkness and blank space, as far as an iron testing-rod could reach, showed that whatever lay beyond was empty, and not filled like the passage we had just cleared. Candle tests were applied as a precaution against possible foul gases, and then, widening the hole a little, I inserted the candle and peered in, Lord Carnarvon, Lady Evelyn and Callender standing anxiously beside me to hear the verdict. At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold.[45]

Carnarvon asked Carter if he could see anything. Accounts differ as to the wording of Carter's answer; in the best-known version, in his book, Carter replied "Yes, wonderful things."[44][Note 3]

Beginning of clearance

The gilded furniture and statuary that Carter saw when first looking into the tomb stood in a room that came to be known as the antechamber.[47] This room alone contained burial goods in greater quantity than the excavators had ever expected. Some were types of object that were very familiar from previous finds; some were exceptionally elaborate examples of their kind; and some were entirely unexpected.[48][49] From the antechamber led two doorways that had been blocked with plaster and then breached by ancient robbers. One was left open, revealing that the chamber beyond, dubbed the annexe, was filled with a chaotic jumble of objects. The other had been resealed in ancient times. Many of the objects bore Tutankhamun's name, leaving the excavators in no doubt that this was his original burial.[50]

At some point in the days after first peering into the antechamber, the excavators breached the plaster of the blocked doorway.[51] Carter, Carnarvon and Lady Evelyn Herbert squeezed through the hole to find the tomb's burial chamber, which was mostly filled by the set of gilded shrines that enclosed Tutankhamun's sarcophagus.[52] The robbers had gone no further than the outermost shrine.[53] Carter, in particular, may have wanted to be certain of that fact; in 1900 he had opened what he thought was an undisturbed royal tomb, the Bab el-Hosan, in front of many highly placed guests, only to find it nearly empty.[54][55]

The excavators resealed the hole with new plaster,[51] though their breach of the doorway became something of an open secret in the Egyptological community.[52] Later Egyptologists have held differing opinions on the excavators' actions. T. G. H. James, Carter's biographer, argued that entering the burial chamber, before the site had been inspected by officials from the Antiquities Service, did not violate the terms of Carnarvon's concession or the standards of behaviour among archaeologists in the 1920s.[56] Joyce Tyldesley asserts that it was against the terms of the concession and points out that the breach necessitated moving some of the artefacts that stood in front of the partition, meaning their original positions could not be recorded.[57]

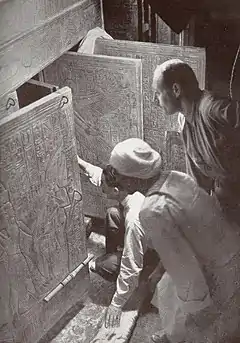

Clearing the tomb of its artefacts would require an unprecedented effort.[58] Moisture from flash floods in the valley above had periodically seeped into the tomb over the centuries. As a result, alternating periods of humidity and dryness had warped wood, dissolved glue and caused leather and textiles to decay. Every exposed surface was covered with an unidentified pink film. Carter later estimated that without intensive restoration efforts, only a tenth of the burial goods would have survived being transported to Cairo.[59] He needed assistance, and he called upon Albert Lythgoe, head of the Egyptian Expedition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was working nearby, to loan some of its personnel. Lythgoe sent Mace, a specialist in conservation; Harry Burton, regarded as the best archaeological photographer in Egypt; and the architect Walter Hauser and the artist Lindsley Hall, who drew scale drawings of the antechamber and its contents.[60] Other experts also volunteered their services: Alfred Lucas, a chemist for the Antiquities Service, whose expertise would be a great help in the conservation effort; James Henry Breasted and Alan Gardiner, two of the foremost scholars of the Egyptian language of the time, to translate any texts discovered in the tomb; and Percy Newberry, a specialist of botanical specimens, and his wife Essie, who helped conserve textiles from the burial.[61][62][Note 4] They used the entrance of KV15, the tomb of Seti II, as a storeroom and conservation laboratory; KV55 as a photographic darkroom; and KV4, the tomb of Ramesses XI, as a place to take meals.[64] Four Egyptian foremen – Ahmed Gerigar, Gad Hassan, Hussein Abu Awad and Hussein Ahmed Said – also worked in the tomb, and a handful of Egyptian porters, whose names are not recorded, carried objects from Tutankhamun's tomb to KV15.[65]

On 16 December the excavators began clearing the antechamber, starting with the objects north of the entrance and moving anti-clockwise around the room.[66] Objects were labelled with reference numbers and photographed in situ before being moved.[67] Carter said of the stacks of furniture and other objects in the antechamber, "So crowded were they that it was a matter of extreme difficulty to move one without running serious risk of damaging others, and in some cases they were so inextricably tangled that an elaborate series of supports had to be devised to hold one object or group of objects in place while another was being removed."[68] The disorganised contents of boxes had to be sorted through, and in some cases pieces of a single object, such as an elaborate inlaid corselet, were scattered through the chamber and had to be searched for before being reassembled.[69] Upon removal from the tomb, the objects were cleaned and, if necessary, treated with preservatives such as celluloid solution or paraffin wax.[70] The items in most urgent need of conservation were treated on the spot, but most were removed to KV15 for treatment.[68]

Tutmania

The tomb inspired a public craze that came to be known as "Tutmania", a specific instance of the long-standing phenomenon of Western Egyptomania.[71] As Breasted's son Charles put it, the news of the discovery "broke upon a world sated with post-First World War conferences, with nothing proved and nothing achieved, after a summer journalistically so dull that an English farmer's report of a gooseberry the size of a crabapple achieved the main news pages of the London metropolitan dailies."[72] The resulting media frenzy was unprecedented in the history of Egyptology.[73] Carter and Carnarvon became internationally famous,[74] and Tutankhamun, formerly unknown to the public, became so familiar as to be given a nickname, "King Tut".[75]

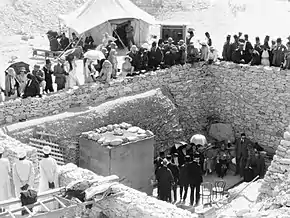

Tourists in Luxor abandoned the normal sightseeing itinerary and flocked to the tomb, crowding around the retaining wall that surrounded the pit in which the tomb entrance lay. At times the excavators feared the wall might collapse from the weight of the people leaning on it. When possible, the excavators left objects uncovered when carrying them out of the entrance, to please the sightseers. People who demanded to enter the tomb, many of whom were too highly positioned or well-connected to refuse, presented a greater difficulty. Every visit to the tomb by a non-archaeologist increased the risk of damage to the burial goods and disrupted the excavators' work schedule; Carter and Mace estimated that a quarter of the work time during the first season was given over to accommodating such visitors.[76]

The phenomenon extended far beyond the tomb itself. Guests at the Winter Palace Hotel in Luxor danced to the "Tutankhamun Rag",[77] and in the United States the discovery inspired a flurry of ephemeral Egypt-themed films and a more enduring hit song, "Old King Tut".[78] Interest in Egyptology, and sales of books about ancient Egypt, also surged;[79] several established Egyptologists published books about Tutankhamun to capitalise on the trend.[80]

The opulence of Tutankhamun's burial goods, in particular, caught the public's attention.[81] Replicas of them appeared as early as 1924, when the British Empire Exhibition featured a reproduction of the tomb, though many of the contents could not be included, as they had not yet been seen even by the excavators.[82] The public in Europe and the United States compared the everyday items in the tomb to modern household goods, and producers of clothing, jewellery, furniture and household decor hastened to create Egyptian-inspired designs. Some were based on actual artefacts found in the tomb; others simply adopted ancient Egyptian names and motifs. Although Egyptian Revival decorative arts had existed since the early nineteenth century, they had largely been aimed at the world of wealthy art connoisseurs. The products of Tutmania were mass-produced and marketed to the public.[83]

In the nineteenth century Egyptians had little interest in ancient Egyptian civilisation.[84] In the early twentieth century that attitude changed, largely because of Ahmed Kamal, one of the first Egyptian Egyptologists, who raised public awareness of ancient Egyptian history.[85][86] In the years leading up to the First World War, Egyptian nationalists began treating ancient Egypt as a source of national identity, one that bound together Egypt's Muslims and Coptic Christians and emphasised that Egypt had once been powerful and independent.[87][88] This ideology, known as Pharaonism, was well established by the time of the 1919 revolution. The Western mania for ancient Egypt had inspired modern Egyptians to adopt it as a source of national pride, and Tutankhamun in particular became a national symbol once Tutmania emerged.[89] After the discovery, ancient imagery became ubiquitous in Egyptian print media, and ancient Egypt became a common subject for Egyptian plays and novels. Major Egyptian literary figures, such as the poet Ahmed Shawqi, focused on Pharaonist themes in the wake of the discovery.[90] The first Egyptian film, made in 1923, was titled In the Country of Tut-Ankh-Amun.[91]

Carnarvon embraced the publicity, hoping to defray the costs of the excavation by licensing rights to the media.[92] On 9 January 1923 he signed a contract with The Times, granting its reporter, Arthur Merton, exclusive press access to the tomb.[93] Other Egyptological digs had made similar arrangements with newspapers in the past, but the unique nature of the Tutankhamun find made this one a major source of conflict.[94] A coalition of other press outlets criticised the Times monopoly on official information from the excavation,[95] and their coverage of Carnarvon grew increasingly negative.[96] Egyptian papers joined the international press in denouncing the monopoly, which they saw as a sign of continued foreign domination. At the same time Pharaonist authors expressed fear that the tomb would be subject to a division of finds, sending many of the burial goods out of the country. An editorial in Al-Ahram, written by Fikri Abaza, declared "Lord Carnarvon is exploiting the mortal remains of our ancient fathers before our eyes, and he fails to give the grandchildren any information about their forefathers".[97]

Death of Carnarvon and the "curse of Tutankhamun"

The antechamber was almost entirely cleared by mid-February,[98] and on 16 February Carter and Carnarvon formally opened the burial chamber with government officials in attendance.[99] At the east end of the burial chamber was an open doorway to a fourth room, dubbed the treasury. It contained the canopic chest that housed Tutankhamun's embalmed organs. Carter had the entrance to this chamber boarded up so it would not be a distraction during the upcoming clearance of the burial chamber; it was only reopened in 1927.[100]

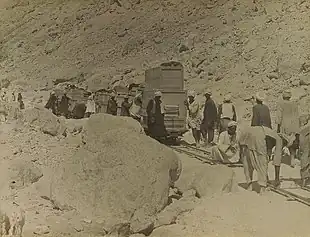

After a viewing period for the press and the general public, the tomb was closed for the season on 26 February.[101] As in each subsequent season, a large temporary workforce of local workmen was recruited to rebury the tomb entrance to prevent intrusion,[102][103] while the objects that had been conserved were packed up for the workmen to propel by hand along a length of Decauville railway track.[104][105] The limited length of available track had to be constantly taken up and re-laid to cover the distance down to the Nile, where the artefacts were shipped to Cairo.[104]

Shortly after the tomb was closed, Carnarvon accidentally cut open a mosquito bite on his cheek while shaving. The wound became infected, and after weeks of illness, culminating in blood poisoning and pneumonia, he died on 5 April.[106] Carnarvon had been in frail health for twenty years, but his death soon attracted speculation that something more than infectious disease was at work.[107]

Works of fiction in which Egyptian spirits or reanimated mummies exact revenge upon those who disturb their tombs first appeared in the late nineteenth century.[108][109] This fictional trope came to be known as the "mummy's curse" or "curse of the pharaohs".[110] The real-life stories of Walter Ingram, who died in 1888 after purchasing an Egyptian mummy, and of a coffin lid called the "Unlucky Mummy", which was purported to cause a variety of misfortunes, cemented the idea of the curse in the public imagination.[111] Now the pre-existing concept was applied to Carnarvon's death.[112]

Several people, such as the author Marie Corelli and a psychic known as Cheiro, claimed to have warned Carnarvon of mortal peril before his death.[113] Arthur Weigall, a former Egyptologist who was now the Daily Mail correspondent on the tomb, said he had observed Carnarvon joking as he entered the tomb and remarked "If he goes down in that spirit, I give him six weeks to live!"[114] Later accounts, such as the recollections of the anthropologist Henry Field, claimed that an ancient text wishing death upon violators of the tomb was inscribed over its doorway or on an object within.[115] No written curse has ever been documented in Tutankhamun's tomb, and although some Egyptian tombs did contain such curses, most are from non-royal tombs that predate Tutankhamun by centuries.[116]

Any deaths or unusual events connected with the tomb were treated as possible results of the curse. Carnarvon's son and heir, Henry Herbert, 6th Earl of Carnarvon, said that Cairo suffered a power outage at the moment of his father's death, and in England his father's dog let out a howl and died.[117] Another such story, recounted by Carter and others involved in the excavation,[118][119] involved a canary that Carter had bought at the beginning of the digging season.[120] Initially the Egyptian workmen regarded the bird as sign of good luck, and when the tomb was discovered they dubbed it "the tomb of the bird." When a cobra entered Carter's house and ate the canary, the Egyptians called it an ill omen, relating the intruding animal to the uraeus, the protective cobra emblem, on the brow of Tutankhamun's statues.[121][122] When George Jay Gould, who had visited the tomb, died the following May, his death was attributed to the curse, as was that of Aubrey Herbert, Carnarvon's half-brother, in September.[123][124] Later additions to the list of purportedly cursed deaths included those of Mace in 1928,[125] Carnarvon's secretary Richard Bethell in 1929 and Weigall in 1934.[126] Most Egyptologists dismissed such claims.[127] In subsequent decades, some sources, such as the author Philipp Vandenberg, suggested natural explanations for the fatalities, such as poisons present in the tomb,[128] but a study in the British Medical Journal in 2002 found no significant difference in mortality between those who had entered the tomb and those who had not.[129]

Egyptian writers picked up the trope of the curse and adapted it for their own purposes. Al-Ahram published humorous stories in which Tutankhamun awoke from death to comment on the politics of the day. More serious works of fiction depicted mummies confronting the Westerners who disturb their tombs, although in a more benign manner than in the Western stories on the same theme. These stories portrayed mummies not as objects of horror but as national ancestors seeking to redress the treatment of Egypt and its heritage by foreign powers.[130]

Second season

Between digging seasons, Carter and Mace wrote the first volume of The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, their account of the discovery and the work that had been done thus far; it was published in October as Carter headed back to Egypt to resume work.[131] With Carnarvon's death, the tomb clearance would be financed by Carnarvon's widow, Almina Herbert, Countess of Carnarvon, but with Carter now the spokesman to the government and the press.[132]

Entering the burial chamber

The season began with the removal of the two life-size statues of Tutankhamun standing in the antechamber on either side of the chamber doorway. After that the excavators began to remove the sarcophagus shrines, which took up most of the burial chamber and left the excavators with little room to move.[133] The partition wall between the antechamber and burial chamber – which bore a portion of the painted decoration of the burial chamber wall[134] – had to be partly demolished to give the excavators room to manoeuvre, and scaffolding had to be erected so the shrines could be dismantled from the top down.[135]

Friction increased between the excavators and the Antiquities Service as Carter sought to strictly limit visitors to the tomb. Lacau required an Antiquities Service inspector on site and demanded that Carter submit a list of all his personnel for government approval. This regulation has since become standard on Egyptological digs but was novel at the time, and in this case it was clearly aimed at Merton, whom Carter had appointed as a member of the excavation team.[136]

Lacau mentioned the division of finds in a 10 January 1924 letter to Carter,[137] raising a topic the excavators had previously avoided.[138] In 1922 Lacau had declared the end of the traditional half-share given to excavators; the government might grant artefacts to the sponsors of an excavation as gifts, but all antiquities in Egypt belonged in principle to the government. This change did not apply to Carnarvon's existing concession, which allowed for a division of finds except in case of an intact tomb, whose contents must be surrendered entirely to the Antiquities Service.[137] Carnarvon had planned to argue that Tutankhamun's tomb did not qualify as intact because it had been robbed, even though it was restored and resealed in ancient times. He had expected to receive a share of the artefacts and had promised that the Metropolitan Museum would be "well taken care of", receiving a portion of his share, in exchange for its assistance.[139] Lacau now implied that all the tomb's contents were property of the Egyptian government, meaning no division of finds would take place.[140]

Other Egyptologists worried that the regulations Lacau was imposing would hamper Egyptological work. Lythgoe, Gardiner, Breasted and Newberry sent a letter of protest to Lacau and his superior, the minister of public works, asserting that the Tutankhamun discovery "belongs not to Egypt alone but to the entire world". This further inflamed the political tensions.[141] The Egyptian elections of January 1924 had brought the Wafd Party to power, forming a nationalist government headed by Prime Minister Saad Zaghloul.[142] The letter thus went to the Wafd's new minister of public works, Morcos Bey Hanna,[141] who was not inclined to be accommodating towards Britons, as the British government had put him on trial for treason for his actions during the Revolution of 1919.[143][144]

Once the shrines were disassembled, the excavators rigged a system of pulleys to lift the lid of the stone sarcophagus, an especially delicate task because it was cracked. On 12 February the lid was raised, revealing, beneath a shroud, a gilded and inlaid wooden coffin in human shape, bearing Tutankhamun's face – the outermost of a nested set. It was the first complete set of royal coffins ever found, and its artistic quality and state of preservation impressed even the experienced Egyptologists who were present.[145]

Strike and lawsuit

A viewing of the coffin by the Egyptian press was scheduled for 13 February, followed by a tour for the excavators' wives and families.[146] Hanna saw this tour as a slight – he pointed out that wives of Egyptian cabinet ministers had not been allowed into the tomb[147] – and forbade the families' visit, sending a police force to ensure his order was carried out.[148] Carter and his collaborators were incensed, and they announced they were halting work in protest of what they called "impossible restrictions and discourtesies" imposed by the Egyptian government. Carter locked the tomb, where the sarcophagus lid was still suspended above the coffin.[149] Hanna terminated the Carnarvon concession, and Lacau brought workmen to the tomb to saw off Carter's locks and secure the sarcophagus lid.[150] The government held a lavish event at the tomb to celebrate its reopening, attended by officials and celebrity guests.[151]

The attendance of British officials at the reopening ceremony signalled that the British government would not support Carter in the dispute.[Note 5] Nevertheless he sued the Antiquities Service in the Mixed Courts of Egypt, a colonial institution for resolving disputes involving non-Egyptians.[154] He used Carnarvon's lawyer, F. M. Maxwell, a politically insensitive choice, as Maxwell had been the prosecutor in Hanna's treason trial and sought the death penalty for him. In March Maxwell remarked in court that the government had seized control of the tomb "like a bandit".[155] In Arabic the word for "bandit" is so profound an insult that news of the remark provoked riots in Cairo.[156] The Mixed Courts ultimately ruled in Carter's favour, but Hanna took the case to a higher court, which on 31 March issued a decision that fully supported his actions.[155][157]

Carter had left Egypt on 21 March, setting out on a lecture tour in the United States and Canada. His absence eased the tensions surrounding the tomb, as did the impending retirement of Maxwell, who began transferring his responsibilities to a more conciliatory lawyer, Georges Merzbach.[158][159] Meanwhile Hanna attempted to find another Egyptologist to complete the tomb clearance, but none were willing to take on the task.[160]

In April, the Egyptian government sent a committee to inspect the excavators' unfinished work in the valley. Among the materials stored in the tombs, they discovered a wooden bust of Tutankhamun emerging from a lotus flower, packed in a crate, that was not included in Carter's excavation notes. The Egyptian members of the committee suspected Carter had intended to surreptitiously remove the bust from the site. When asked about it by telegram, Carter responded that the bust had been among the objects found in the entrance corridor, and that he and Callender had packed it because of its fragile state.[161]

The political situation in Egypt changed dramatically on 19 November 1924, when Sir Lee Stack, the sirdar of the Egyptian Army, was assassinated by nationalists. The furious British reaction drove Zaghloul to resign. His successor, Ahmed Zeiwar Pasha, formed a more pro-British government, with which the parties involved in the tomb clearance were able to reach an agreement. Carter would continue to oversee the clearance; Lady Carnarvon would continue to fund it but renounced her claim to a share of the burial goods;[Note 6] and the Times monopoly was ended. Carter resumed work on 25 January 1925.[163][164]

Later seasons

Resumption of work and Tutankhamun's burial

In the shortened and uneventful third season of the dig, the excavators removed nothing but worked to conserve the objects already in the laboratory tomb.[164] Thus press interest quickly dwindled,[164] and although coverage flared up when Tutankhamun's mummy was unwrapped, the remainder of the clearance took place out of the media spotlight.[166]

Over the following summer Callender, who objected to his loss of income from the shortening of the season, fell out with Carter and resigned.[167] Burton, Lucas and the foremen were thus Carter's only consistent collaborators during the remainder of the process.[168]

The fourth season began in late 1925 and focused on Tutankhamun's burial itself.[169] His mummy lay within a nested series of three coffins, of which the innermost was mainly composed of 110.4 kilograms (243 lb) of solid gold. On his body, and within his mummy wrappings, the king bore a plethora of jewellery and other objects, including a gold burial mask.[170] The inner coffin and the mummy had both been covered in unguents at burial. These unguents had solidified into hard resin, gluing the mummy and its trappings into a single mass stuck to the bottom of the inner coffin, which was in turn stuck to the bottom of the middle coffin.[171] The unguents had undergone a chemical reaction that had carbonised the linen mummy wrappings, and even some of the tissues of the mummy itself, rendering Tutankhamun's flesh extremely fragile.[172][173] The excavators first tried to melt the resin by taking the coffins out of the tomb to be heated by the sun, but this failed.[174] Therefore, Tutankhamun's remains were still in place within the coffins when the anatomists Douglas Derry and Saleh Bey Hamdi began examining them on 11 November 1925. Over the course of eight days they dismembered the mummy and individually chiselled the pieces out of the mass of resin, removing the burial goods as they did so, and examined the pieces individually.[175]

Once the examination was complete the excavators began separating the coffins. They built trestles to suspend the conjoined coffins upside-down, then placed paraffin lamps underneath to raise the temperature to 500 °C (932 °F), shielding the coffins from the heat using wet blankets and plates of zinc. Once the coffins were pulled apart, the remaining resin was cleared away with solvents.[176][177]

In this season Carter established a pattern of work that continued for the rest of the clearance process: in the first months of the season the excavators would remove objects from Tutankhamun's tomb, then after the new year open it to the public while concentrating on conserving the objects in the laboratory tomb.[178] Though the excavators had hoped to clear the treasury during the fourth season, the unexpected challenges of the burial chamber forced them to wait another year.[179]

Treasury, annexe and completion

When resuming work in the fifth season Carter rearranged the pieces of the mummy to look whole once again, then placed them in the outermost coffin and covered the sarcophagus with a plate of glass instead of the original lid. With this done, the excavators dismantled the barrier to the treasury and began sorting through its contents: a shrine of the god Anubis, more boxes of belongings such as jewellery, wooden tomb models of boats and the canopic chest that contained the internal organs that were removed from Tutankhamun's body during embalming. The room's most unexpected contents were the mummies of two fetuses, which are presumed to be Tutankhamun's stillborn children.[180]

In early 1927 Carter published the second volume of The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, written with substantial anonymous help from a friend, the novelist Percy White. In the following season the excavators faced the annexe, which contained more than half of the individual objects in the entire tomb.[181] The floor of this room was entirely covered with haphazardly piled burial goods and lay nearly a metre below the floor of the antechamber. To start work in the annexe the excavators had to clear enough space to stand in the room by having one man lean through the doorway at a precarious angle, supported by slings held by three or four others standing in the antechamber. The last object was removed from the annexe on 15 December, and the rest of the season was spent on conservation.[182]

Little was achieved in the sixth season, as Lucas and Burton developed illnesses that prevented them from working for several weeks. The seventh saw more contention between Carter and the authorities, as the Carnarvon concession expired in 1929 and ownership of the tomb reverted to the Egyptian government. Egyptian law forbade anyone not employed by the government to possess the keys to government property, and Carter objected to having to rely on a government inspector to open the tomb for him each day. In early 1930, the government came to its final settlement with Lady Carnarvon, compensating her with a payout for the expenses incurred during the excavation.[183]

The final challenge involved conserving the dismantled pieces of the shrines, which were still stacked in the antechamber.[182] Harold Plenderleith, a scientist at the British Museum, intermittently assisted Carter and Lucas with this task.[184] The last of the shrine pieces were removed from the tomb in November 1930. Conservation of objects continued until February 1932, when the last burial goods were sent to Cairo.[185]

Disposition of artefacts

The artefacts from the tomb were numbered at 5,398 distinct objects.[186] By Carter's estimation, one quarter of a per cent of these objects were damaged beyond repair.[187] Most of the remainder were sent to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo,[188] coming to form about a sixth of the museum's permanent exhibits.[71] The sarcophagus, outermost coffin, and mummy remained in the burial chamber, as did a skullcap and large bib-like broad collar, both made of delicate beadwork, that Carter apparently thought too fragile to remove from the mummy.[189][Note 7]

Retrospective discussion of the clearance tends to emphasize how scrupulous and methodical the process was.[191] Jason Thompson, author of a history of Egyptology, regards Carter as one of the three most skilled archaeologists working in Egypt in his time and says that if Davis had discovered the tomb in 1914, the clearance "would have been substandard at best, and the contents of the tomb probably would have been dispersed".[192] Yet Carter did give out some small objects to visitors to the tomb or to fellow Egyptologists, where they may have found their way into museum collections. Gardiner, for instance, had a falling-out with Carter in 1934 after realising an amulet that Carter had given him had been stolen from the tomb.[193][194] The Egyptologist Bob Brier says of these artefacts that "Carter believed he had a right to do with them as he pleased."[195]

After Carter's death in 1939 his niece and heir, Phyllis Walker, discovered several such objects among his possessions and had them returned to Egypt.[196] In 1978 Thomas Hoving, a former curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, pointed out several items in the museum's collection that were not clearly traceable to the tomb but that he thought likely to have originated there.[197] The museum gave several of these objects to the Egyptian government in 2010.[198]

Documentation

The final volume of The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, covering the treasury and annexe, was published in 1933. Yet the three volumes, aimed at the general public, did not constitute a full archaeological description of the tomb and its contents.[199] The clearance process had produced a large volume of documentation.[200] Nearly every object was catalogued, and most were photographed by Burton, although many minor objects, somewhere between fifteen and twenty per cent of the total, were not photographed.[201] Several experts had produced specialised contributions, such as Derry and Hamdi's anatomical examination and Newberry's botanical studies. Carter hoped to assemble all this material into a formal Egyptological report. Beyond outlining a general six-volume plan, he had not begun on the project by the time he died.[202] The Egyptian Council of Ministers moved to fund a full publication of the tomb in 1951, but the effort died in the wake of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952.[203]

Shortly after Carter's death, Walker donated his journals and notes on the excavation to the Griffith Institute at the University of Oxford. In the 1990s the institute launched an effort to scan this material, which they made available online in the early 2010s.[204][205]

Legacy

When the tomb was discovered, Egyptologists hoped it might contain documents that would clarify the history of the period in which Tutankhamun lived. No such documents were found, but the artefacts did provide clues.[206] The dates on wine jars from the tomb established that Tutankhamun had not reigned much longer than nine years.[207] Egyptologists had previously assumed his only claim to the throne was through his marriage to his queen, Ankhesenamun, and perhaps that he had been an elderly courtier. Yet the examination of the mummy revealed that he was between the ages of 17 and 22 at death, and the unusual shape of his skull resembled that of the unidentified royal mummy from the KV55 tomb, suggesting that he was related to it and was thus of royal blood himself.[208][209] Some artworks from the tomb are in the art style of the Amarna Period, and some refer to the Aten, the deity worshipped in that period, indicating that the return to orthodoxy during Tutankhamun's reign was gradual.[210][211]

Much of the tomb's historical value was in the burial goods, which included sumptuous examples of ancient Egyptian decorative arts and enhanced the understanding of the material culture of the New Kingdom, primarily how royalty lived.[212][213] Many of the clothes from the tomb, for example, are far more varied and embellished than the clothes portrayed in art from Tutankhamun's time.[214] The tomb also provides exceptional evidence about tomb robbery and official restoration efforts, because the presence of most of the burial goods makes it possible to partly reconstruct what was stolen and what was restored.[215]

The discovery marked a change in the history of the Valley of the Kings. Once the clearance was complete, many Egyptologists lost interest in the valley, assuming there was nothing left there to be found.[216][217] What little archaeological work took place in the valley over the next few decades largely consisted of more fully recording what had already been unearthed.[217] No further tombs were discovered in the valley until 2006, when KV63 was found.[218][Note 8]

The discovery also affected Egyptology in a different way: together with Egypt's newfound partial independence, the enthusiasm surrounding Tutankhamun helped stimulate the growth of Egyptian Egyptology.[221] At the time of the discovery very few Egyptians were trained in archaeology, and those few were looked down upon by European Egyptologists.[222] Hamdi was the only Egyptian among the specialised experts who worked on the tomb. The first Egyptian university programme for Egyptology was established in 1924, and over the course of the decade a new generation of Egyptian Egyptologists were trained.[223]

Although Western public interest in Tutankhamun experienced a lull lasting more than thirty years, it was revived after the Egyptian government began sending the burial goods on international museum exhibitions.[166] The exhibitions began in the early 1960s as a means of encouraging Western support for the relocation of ancient Egyptian monuments that were threatened to be flooded by the construction of the Aswan High Dam.[224] Such exhibitions proved highly popular; the one that toured the United States in the 1970s drew more than eight million visitors and moved American museums' business model to focus on lucrative blockbuster exhibitions.[225] Much of the revenue from the exhibitions went to support the monuments' relocation[226] and to pay for improvements to the Egyptian Museum.[227] The exhibitions also served other diplomatic functions, helping to improve Egypt's relations with Britain and France after the Suez Crisis in 1956, and with the United States after the Yom Kippur War in 1973.[228]

Today the discovery remains the most famous find in the Valley of the Kings[229] and Tutankhamun the best-known ruler of ancient Egypt.[230] The Egyptologist Nicholas Reeves writes that thanks to his fame, Tutankhamun "has been reborn as Egypt's most famous son, to achieve true immortality at last."[231] The tomb and its treasures are key attractions for Egypt's tourist industry[232] and sources of pride for the Egyptian public.[233]

Notes

- ↑ The system of numbering tombs in the Valley of the Kings was established in 1827, when the Egyptologist John Gardner Wilkinson labelled 25 tombs that were then known.[3] Other tombs were added to the sequence in order of their discovery. Tutankhamun's tomb is designated KV62.[4]

- ↑ Karl Kitchen, a reporter for the Boston Globe, wrote in 1924 that a boy named Mohamed Gorgar had found the step; he interviewed Gorgar, who did not say whether the story was true.[36] Lee Keedick, the organiser of Carter's American lecture tour, said Carter attributed the discovery to an unnamed boy carrying water for the workmen.[37] Many recent accounts, such as the 2018 book Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh by the Egyptologist Zahi Hawass, identify the water-boy as Hussein Abd el-Rassul, a member of a prominent local family. Hawass says he heard this story from el-Rassul in person. Another Egyptologist, Christina Riggs, suggests the story may instead be a conflation of Keedick's account, which was widely publicised by the 1978 book Tutankhamun: The Untold Story by Thomas Hoving, with el-Rassul's long-standing claim to have been the boy who was photographed wearing one of Tutankhamun's pectorals in 1926.[38]

- ↑ According to the notes Carter wrote soon after the discovery, he said "Yes, it is wonderful." In an account that Carnarvon wrote for the Times, Carter said "There are some marvelous objects here." The more evocative wording in Carter's published account may have been devised by Mace.[46]

- ↑ Sergeant Richard Adamson, a military policeman at the time of the discovery,[63] claimed beginning in 1966 to have guarded the tomb for seven seasons.[64] Journalists thereafter treated him as the last surviving member of the excavation team. He does not appear in any photographs or contemporary accounts of the discovery, and documents of his life suggest he was not in Egypt at some of the times he claimed to have been.[64]

- ↑ In 1978 Hoving alleged, based on Keedick's notes,[119] that when meeting the British vice-consul in Egypt during the dispute with the Egyptian government in 1924, Carter claimed to have found documents in the tomb that contained "the true and scandalous account of the exodus of the Jews from Egypt".[152] According to Hoving there were no such documents, and Carter was lashing out in frustration at the British authorities' refusal to support him by threatening to destabilise relations between Jews and Arabs in British-controlled Mandatory Palestine.[153] James wrote in 2000 that Hoving's description of this event "goes far beyond the facts as recorded by Keedick", whose notes were "quite unspecific as to place, time and even the persons involved". James concluded "There is no independent witness for the event, and it may best be described as apocryphal."[119]

- ↑ The agreement included a vague provision that the government might give some objects from the tomb to Lady Carnarvon as gifts, but in the end no such gifts were given.[162]

- ↑ The skullcap and collar were stolen from off the mummy during an undocumented robbery of the tomb, at some point between Tutankhamun's reinterment in 1926 and a re-examination by the anatomist Ronald Harrison in 1968.[190]

- ↑ Royal tombs from periods other than the New Kingdom continued to be discovered, such as Pierre Montet's discovery of the Third Intermediate Period burials at Tanis in 1939–1940. These burials were comparable in opulence to that of Tutankhamun and included a tomb that had never been robbed, that of Psusennes I, but the finds received far less attention, as they took place during the early stages of the Second World War.[219][220]

References

Citations

- ↑ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 9, 14–15.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 18–20.

- ↑ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Wilkinson & Weeks 2016, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 24–27.

- ↑ Thompson 2015, pp. 2–4.

- ↑ Reid 2015, pp. 2–5.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 224.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 28.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Dorn 2016, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Price 2016, pp. 274–275.

- 1 2 Reeves 1990, pp. 37, 41.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 39.

- ↑ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 72–75.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, p. 14.

- ↑ Thompson 2015, pp. 250–252.

- ↑ Thompson 2015, pp. 252–255.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 34–37.

- ↑ Thompson 2015, pp. 251–252, 254.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 52–55.

- ↑ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Thompson 2015, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, pp. 44–46, 48–49.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 60.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 248–250.

- ↑ Reid 2015, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 62.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 250–251.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 46.

- ↑ Winstone 2006, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 297.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 255.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, pp. 296–298, 407.

- ↑ Winstone 2006, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 70.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 91–95.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, p. 87.

- 1 2 Frayling 1992, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Frayling 1992, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, p. 103.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, p. 118.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 99–100, 103–104.

- 1 2 Tyldesley 2012, p. 68.

- 1 2 Riggs 2021, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 98.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 69.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 79.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 261.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Carter 2000, pp. 151–152, 163.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, p. 115–116, 170.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Winstone 2006, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Tyldesley 2012, p. 76.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, pp. 9, 154–155.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 59.

- 1 2 Carter & Mace 2003, p. 123.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 173–175.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 78.

- 1 2 Fritze 2016, p. 240.

- ↑ Breasted 2020, p. 345.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 1.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 49.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 93.

- ↑ Carter & Mace 2003, pp. 143–147.

- ↑ Frayling 1992, p. 10.

- ↑ Coniam 2017, pp. 42, 53–54.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 313.

- ↑ Frayling 1992, pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 266.

- ↑ Frayling 1992, pp. 10–12, 17–19.

- ↑ Haikal 2003, p. 123.

- ↑ Haikal 2003, p. 125.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 29.

- ↑ Reid 2015, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Colla 2007, p. 213.

- ↑ Reid 2015, pp. 12, 42, 74.

- ↑ Colla 2007, pp. 211–215.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 67.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 278–279.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 74.

- ↑ Winstone 2006, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Reid 2015, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 81.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 284–286.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 86.

- ↑ Winstone 2006, pp. 186–187, 193.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 56.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, p. 9.

- 1 2 Reeves 1990, p. 60.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, p. 155.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 84.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, pp. 44, 62.

- ↑ Day 2006, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Luckhurst 2012, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Day 2006, p. 4.

- ↑ Luckhurst 2012, pp. 26–28, 61–62.

- ↑ Day 2006, p. 50.

- ↑ Fritze 2016, p. 237.

- ↑ Frayling 1992, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Luckhurst 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ Ritner 1997, p. 146.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, p. 54.

- ↑ White 2003, pp. vii–ix.

- 1 2 3 James 2000, p. 352.

- ↑ Frayling 1992, p. 55.

- ↑ White 2003, pp. xi–xiv.

- ↑ Breasted 2020, pp. 342–343.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 63.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, p. 229.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 426.

- ↑ Luckhurst 2012, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Frayling 1992, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Day 2006, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Nelson 2002, pp. 1483–1484.

- ↑ Colla 2007, pp. 222–224.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 312, 314.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 85.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 87.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 73–74.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 97.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 86–87.

- 1 2 Reid 2015, p. 65.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, p. 24.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 328.

- 1 2 Thompson 2018, p. 65.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 54.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 91.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 335–336.

- ↑ Winstone 2006, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 70.

- ↑ Winstone 2006, p. 228.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 346.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, pp. 100–101.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, p. 311.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, pp. 311–312.

- ↑ Reid 2015, pp. 70–71.

- 1 2 Thompson 2018, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, p. 306.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, p. 316.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 68–69.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 353, 366.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, pp. 308–309.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 363–365.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 382, 432.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 379–383.

- 1 2 3 Tyldesley 2012, p. 93.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 58.

- 1 2 Reid 2015, p. 63.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 390–391.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, p. 12.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 94.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 110–112.

- 1 2 Marchant 2013, p. 62.

- ↑ Carter 2001, p. 101.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, p. 69.

- ↑ Carter 2001, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, pp. 64, 69–72.

- ↑ Carter 2001, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, p. 73.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 412–413.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 412.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, pp. 74–77.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 415, 421.

- 1 2 Tyldesley 2012, p. 99.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 425–426, 432–434.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 108.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 100.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 54.

- ↑ Carter 2000, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 71.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, pp. 74, 97.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 52, 70.

- ↑ Brier 2022, pp. 254–255.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 115.

- ↑ Brier 2022, p. 255.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, pp. 116–119.

- ↑ Hoving 1978, pp. 350–351.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 119.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 73.

- ↑ James 2000, p. 445.

- ↑ Riggs 2019, p. 108.

- ↑ James 2000, pp. 445, 468.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, p. 75.

- ↑ Griffith Institute.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, pp. 167, 202.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Marchant 2013, p. 72.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 153.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 126–128.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 105.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 12.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 108.

- ↑ Goelet 2016, pp. 451–453.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 307.

- 1 2 Tyldesley 2016, p. 492.

- ↑ Cross 2016, p. 520.

- ↑ Brier 2022, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Thompson 2018, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Reid 2015, p. 109.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Reid 2015, pp. 56–57, 118–121.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ Fritze 2016, pp. 241–242.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 201.

- ↑ Fritze 2016, p. 242.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, pp. 179–181, 228–229.

- ↑ Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 8.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Reeves 1990, p. 209.

- ↑ Tyldesley 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ Riggs 2021, p. 346.

Works cited

- Breasted, Charles (2020) [1943]. Pioneer to the Past: The Story of James Henry Breasted, Archaeologist. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. ISBN 978-1-61491-053-4.

- Brier, Bob (2022). Tutankhamun and the Tomb that Changed the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-763505-6.

- Carter, Howard; Mace, A. C. (2003) [1923]. The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume I: Search, Discovery and Clearance of the Antechamber. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3172-0.

- Carter, Howard (2001) [1927]. The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume II: The Burial Chamber. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3075-4.

- Carter, Howard (2000) [1933]. The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume III: The Annexe and Treasury. Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-2964-2.

- Colla, Elliott (2007). Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-3992-2.

- Coniam, Matthew (2017). Egyptomania Goes to the Movies: From Archaeology to Popular Craze to Hollywood Fantasy. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-6828-4.

- Cross, Stephen W. (2016). "The Search for Other Tombs". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 517–527. ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7.

- Day, Jasmine (2006). The Mummy's Curse: Mummymania in the English-Speaking World. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-46286-7.

- Dorn, Andreas (2016). "The Hydrology of the Valley of the Kings". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 30–38. ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7.

- Frayling, Christopher (1992). The Face of Tutankhamun. Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-16845-3.

- Fritze, Ronald H. (2016). Egyptomania: A History of Fascination, Obsession and Fantasy. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-639-1.

- Goelet, Ogden (2016). "Tomb Robberies in the Valley of the Kings". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 448–466. ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7.

- Haikal, Fayza (2003). "Egypt's Past Regenerated by Its Own People". In MacDonald, Sally; Rice, Michael (eds.). Consuming Ancient Egypt. UCL Press. pp. 123–138. ISBN 978-1-84472-003-3.

- Hoving, Thomas (1978). Tutankhamun: The Untold Story. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-24370-8.

- James, T. G. H. (2000). Howard Carter: The Path to Tutankhamun, Second Edition. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-615-7.

- Luckhurst, Roger (2012). The Mummy's Curse: The True History of a Dark Fantasy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-969871-4.

- Marchant, Jo (2013). The Shadow King: The Bizarre Afterlife of King Tut's Mummy. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82133-2.

- Nelson, Mark R. (2002). "The Mummy's Curse: Historical Cohort Study". The British Medical Journal. 325 (7378): 1482–1484. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7378.1482. PMC 139048. PMID 12493675.

- Price, Campbell (2016). "Other Tomb Goods". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 274–289. ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7.

- Reeves, Nicholas (1990). The Complete Tutankhamun. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05058-3.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05080-4.

- Reid, Donald Malcolm (2015). Contesting Antiquity in Egypt: Archaeologies, Museums & the Struggle for Identities from World War I to Nasser. The American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-938-0.

- Riggs, Christina (2019). Photographing Tutankhamun: Archaeology, Ancient Egypt, and the Archive. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-350-03851-6.

- Riggs, Christina (2021). Treasured: How Tutankhamun Shaped a Century. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-5417-0121-2.

- Ritner, Robert K. (1997). "The Cult of the Dead". In Silverman, David P. (ed.). Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 132–147. ISBN 978-0-19-521952-4.

- Thompson, Jason (2015). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology, 2. The Golden Age: 1881–1914. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-692-1.

- Thompson, Jason (2018). Wonderful Things: A History of Egyptology, 3. From 1914 to the Twenty-First Century. American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-977-416-760-7.

- "Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation". The Griffith Institute. Griffith Institute. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2012). Tutankhamen: The Search for an Egyptian King. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02020-1.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2016). "The History of KV Exploration Prior to the Late Twentieth Century". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 481–493. ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7.

- White, Percy (2003) [Reprint from Pearson's Magazine, 1923]. "The Tomb of the Bird". The Tomb of Tut.ankh.Amen, Volume I: Search, Discovery and Clearance of the Antechamber. By Carter, Howard; Mace, A. C. Duckworth. pp. vii–xiv. ISBN 978-0-7156-3172-0.

- Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (2016). "Introduction". In Wilkinson, Richard H.; Weeks, Kent R. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–12. ISBN 978-0-19-993163-7.

- Winstone, H. V. F. (2006). Howard Carter and the Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, Revised Edition. Barzan Publishing. ISBN 978-1-905521-04-3.

External links

- Archived records from the tomb clearance at the website of the Griffith Institute