| KV44 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of unknown | |

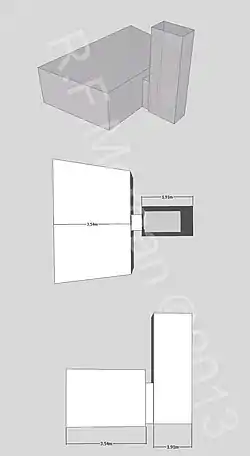

Schematic of KV44 | |

KV44 | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′24.5″N 32°36′10.8″E / 25.740139°N 32.603000°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 26 January 1901 |

| Excavated by | Howard Carter (1901) Donald P. Ryan (1991) |

KV44 is an ancient Egyptian tomb located in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It was discovered and excavated by Howard Carter in 1901 and was re-examined in 1991 by Donald P. Ryan. The single chamber accessed by a shaft contained three intact Twenty-second Dynasty burials; the remains of seven mummies from the original interment were found within the fill. The original cutting of the tomb is dated to the Eighteenth Dynasty.[1]

Location, discovery and layout

KV44 is located in a small side wadi that runs east from the main valley. It is located near KV28 and next to KV45.[2] The location of the tomb was already known in Western Thebes some time before late January 1901 and was opened by Howard Carter on 26 January 1901 after two days of excavation. The tomb consists of a shaft 5.5 metres (18 ft) deep ending in a single chamber. The doorway to the room was securely, if roughly, sealed.[3]

Contents

The chamber was partly filled with water-washed earth. On top of this fill sat three wooden coffins placed beside each other against one wall and draped in floral wreaths. Nearest the wall was a black-painted wooden coffin with yellow decoration and red text; this coffin contained the well wrapped mummy of Iuf'a.[3][4] Beside this was another coffin, also painted black with yellow designs but with inlaid eyes housing a cartonnage coffin covered in resin; inside was a mummy identifiable only as a chantress by the legible portion of the inscription.[3] However, Porter and Moss identify her as Keramama.[4] The third coffin was of rough wood but contained a beautifully decorated cartonnage coffin; inside was the well wrapped mummy of Tentkeresherit, fitted with red leather mummy braces stamped at the ends with the cartouche of Osorkon I.[3][4] Percy Newberry identified the floral wreaths as being composed of Mimusops, Mimosa nilotica, Centaurea depressa, and Nymphaea cerulea.[3]

These three burials were not the original occupants however, as Carter noted that the room was a fifth full of debris "amongst which were remains of earlier mummies without either coffins or funeral furniture". The tomb had evidently stood open for some time in the past as several bee nests were seen on the ceiling.[3]

Re-investigation

In 1991 the tomb was re-investigated by the Pacific Lutheran University Valley of the Kings Project headed by Donald P. Ryan. Other than removing the three coffins to Cairo, Carter had undertaken little work in the tomb. Careful excavation of the fill recovered the remains of seven individuals; two were young women, and three were children including one two year-old.[5][6] The foot board of a child's coffin was also found along with an uninscribed piece of a canopic jar. Small finds included pottery fragments and a blue cylinder bead.[1]

The project resumed in 2005, and found that water had penetrated several of the tombs under study, likely during the 1994 flood events. All artefacts from KV44 and KV45, barring pottery and human remains, were moved to KV21 for protection from further flooding.[5]

Intended occupants

The intended occupants of KV44 are not known. Elizabeth Thomas proposed that this was a tomb for Anen, the brother of Tiye, the Great Royal Wife of Amenhotep III. This theory was proposed based on the clustering of late Eighteenth Dynasty tombs in this area and the fact that Anen was not buried in his known intended tomb TT120. However, Ryan's excavations found no material in the tomb to date later than the middle of the Eighteenth Dynasty, and as such there is no archaeological evidence for the burial of Anen within KV44.[7]

Citations

- 1 2 Reeves & Wilkinson 1996, p. 184.

- ↑ Carter 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Carter 1901.

- 1 2 3 Porter & Moss 1964, p. 587.

- 1 2 Ryan 2007.

- ↑ Ryan 1995.

- ↑ Brock 1999.

References

- Brock, Lyla Pinch (1999). "Jewels in the Gebel: A Preliminary Report on the Tomb of Anen". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 36: 71–85. doi:10.2307/40000203. ISSN 0065-9991. JSTOR 40000203. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- Carter, Howard (1901). "Report on a Tomb-Pit Opened on the 26th January 1901, in the Valley of the Kings Between No. 4 and No. 8". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Le Service. II: 144–145. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Carter, Howard (1903). "Report on General Work Done in the Southern Inspectorate". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. Le Service. IV: 43–50. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Porter, Bertha; Moss, Rosalind (1964). Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings Volume I: The Theban Necropolis, Part 2. Royal Tombs and Smaller Cemeteries. Griffith Institute. Retrieved 16 April 2021.

- Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2010 paperback ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2.

- Ryan, Donald P. (1995). "Further Observations Concerning the Valley of the Kings". In Wilkinson, Richard H. (ed.). Valley of the Sun Kings: New Explorations in the Tombs of the Pharaohs (PDF). Tucson: The University of Arizona Egyptian Expedition. pp. 157–161. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- Ryan, Donald P. (2007). "Pacific Lutheran University Valley of the Kings Project: Work Conducted during the 2005 Field Season". Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte. 81: 345–356.

External links

- Theban Mapping Project: KV44 includes detailed maps of most of the tombs.