| KV61 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of nothing (unused) | |

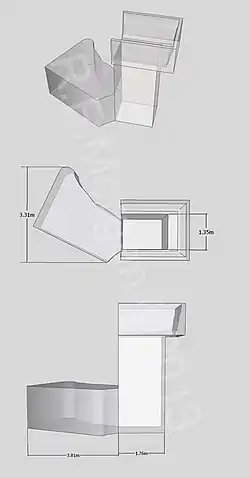

Schematic of the unfinished KV61 | |

KV61 | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′22.2″N 32°36′02.8″E / 25.739500°N 32.600778°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | January 1910 |

| Excavated by | Harold Jones (1910) University of Basel (2017–18) |

Tomb KV61 is an unused tomb in Egypt's Valley of the Kings. It was discovered by Harold Jones, excavating on behalf of Theodore M. Davis, in January 1910. The tomb consists of an irregularly-cut room at the bottom of a shaft. It was apparently unused and undecorated, thus its intended owner is unknown.[1]

Discovery and clearance

Upon discovery, Jones' hopes were high, as the shaft fill appeared undisturbed, and the doorway was securely sealed. Removing the blocking, the chamber was revealed to be half-filled with "water sodden" debris.[2] The excavation ultimately yielded nothing:

Hopeful of finding some evidence of the owner of the tomb... work was carefully proceeded with til ever corner of the tomb was bare and bare were the results – for never even a potsherd was found.[2]

Jones' foreman Ahmed suggested the tomb was not robbed but cleared in antiquity, although Jones doubted that the tomb was used or even finished. Nicholas Reeves concurs with Jones, finding it likely that the tomb was never used, as a dismantled burial would be unlikely to have been cleared as thoroughly nor to have a carefully closed entrance. The tomb entrance was likely blocked up by the quarrymen to await a burial that never eventuated; the muddy fill likely entered the tomb through the blocking during flood events.[2]

Re-clearance

The tomb was re-cleared by the University of Basel Kings' Valley Project during their 2017–2018 season. The tomb was cleared of the modern rubbish that had accumulated inside since it was last visited by the Theban Mapping Project in the 1980s. The unfinished and unused nature of the tomb was confirmed; the ceiling was noted to be low and in bad condition. The entrance is well below the modern ground level, leaving the open tomb vulnerable to future flood events. An iron cover was prepared and, due to the irregular shape of the tomb's entrance, was placed on short modern walls. Clearance in the immediate area around the shaft to prepare for the walls uncovered several ostraca, most affected by humidity, and the remains of the Nineteenth Dynasty workers huts that once covered the area.[3]

References

- ↑ Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings : Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2010 paperback reprint ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2.

- 1 2 3 Reeves, C. N. (1990). Valley of the Kings: Decline of a royal necropolis. London: Kegan Paul International. pp. 171–172. ISBN 0-7103-0368-8.

- ↑ Bickel, Suzanne; Paulin-Grothe, Elina (2018). "Report on work carried out during the field season 2017–2018" (PDF). University of Basel King's Valley Project: 7–9. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

Further reading

- Siliotti, A. Guide to the Valley of the Kings and to the Theban Necropolises and Temples, 1996, A.A. Gaddis, Cairo

External links

- Theban Mapping Project: KV61 includes detailed maps of most of the tombs.