_Detachment_5%252C_based_in_Pearl_Harbor%252C_Hawaii%252C_explains_the_Mk_20_full_face_mask_to_Seychelles_Coast.jpg.webp)

Diver training is the set of processes through which a person learns the necessary and desirable skills to safely dive underwater within the scope of the diver training standard relevant to the specific training programme. Most diver training follows procedures and schedules laid down in the associated training standard, in a formal training programme, and includes relevant foundational knowledge of the underlying theory, including some basic physics, physiology and environmental information, practical skills training in the selection and safe use of the associated equipment in the specified underwater environment, and assessment of the required skills and knowledge deemed necessary by the certification agency to allow the newly certified diver to dive within the specified range of conditions at an acceptable level of risk. Recognition of prior learning is allowed in some training standards.

Recreational diver training has historically followed two philosophies, based on the business structure of the training agencies. The not-for profit agencies tend to focus on developing the diver's competence in relatively fewer stages, and provide more content over a longer programme, than the for-profit agencies, which maximise profit and customer convenience by providing a larger number of shorter courses with less content and fewer skills per course. The more advanced skills and knowledge, including courses focusing on key diving skills like good buoyancy control and trim, and environmental awareness, are available by both routes, but a large number of divers never progress beyond the entry level certification, and only dive on vacation, a system by which skills are more likely to deteriorate than improve due to long periods of inactivity. This may be mitigated by refresher courses, which tend to target skills particularly important in the specific region, and may focus on low impact diving skills, to protect the environment that the service provider relies on for their economic survival.[1]

Diver training is closely associated with diver certification or registration, the process of application for, and issue of, formal recognition of competence by a certification agency or registration authority. The training generally follows a programme authorised by the agency, and competence assessment follows the relevant diver training standard.

Training in work skills specific to the underwater environment may be included in diver training programmes, but is also often provided independently, either as job training for a specific operation, or as generic training by specialists in the fields. Professional divers will also learn about legislative restrictions and occupational health and safety relating to diving work.[2][3]

Comparison between recreational and professional diver training

Both recreational and professional diving occur in the underwater environment, which presents the same basic hazards to both groups. The professional diver has a job to do in this environment, which may expose them to additional hazards associated with the work.[4] The recreational diver usually has no legal duty of care to other divers. The duty of care to a recreational dive buddy is poorly defined and with some exceptions, the diver is not legally obliged to dive with a buddy unless they choose to. The professional diver is a member of a diving team and has legally defined duty of care to other members of the team.[4]

Recreational diver training prepares the diver for low stress diving in an environment similar to the one they were trained in, using equipment similar to that used in training. Professional diver training prepares the diver for a working environment in which the diver is expected to work as a member of a team, and be involved in organisation, planning, setting up of the infrastructure, selection and maintenance of the diving and work related equipment, where conditions may be less than ideal, and there may be time constraints. The professional diver must be able to make a realistic and informed decision on acceptability of risk.[4]

Recreational diver training is regulated within the recreational diver training industry, within each certification agency, and tends to be kept to a minimum to keep costs down in a competitive environment, and because of customer pressure to minimise the effort involved. Consequently, the entry level certification for most recreational divers advises them to dive only in conditions similar to those in which they were trained, and to a maximum depth of 18 m, with no decompression obligation. This also encourages the diver to attend further training if they wish to achieve more than minimum competence. The training is short, convenient, and minimal. The cost is low in absolute terms, but accumulates with further training, for those few who undertake it. Professional diver training, and the associated assessment and certification of competence, are usually based on occupational health and safety legislation, and also covered by the employer's duty of care. The training standards are usually aligned with internationally recognised standards, and are expected to follow quality assurance procedures. The professional diver with entry level qualification is expected to perform duties as working diver, diver's attendant, and standby (rescue) diver, and must be competent and fit to perform all these tasks, as well as the basic skills of staying alive underwater and not getting injured, and the work involved in setting up the site and demobilisation after the job.[4]

Prerequisites

The entry requirements for diver training depend on the specific training involved, but generally include medical fitness to dive.

Fitness to dive, (also medical fitness to dive), is the medical and physical suitability of a diver to function safely in the underwater environment using underwater diving equipment and procedures. Depending on the circumstances it may be established by a signed statement by the diver that he or she does not suffer from any of the listed disqualifying conditions and is able to manage the ordinary physical requirements of diving, to a detailed medical examination by a physician registered as a medical examiner of divers following a procedural checklist, and a legal document of fitness to dive issued by the medical examiner.

The most important medical is the one before starting diving, as the diver can be screened to prevent exposure when a dangerous condition exists. Other important medicals are after some significant illness where medical intervention is needed. This has to be done by a doctor who is competent in diving medicine, and can not be done by prescriptive rules.[5]

Psychological factors can affect fitness to dive, particularly where they affect response to emergencies, or risk taking behaviour. The use of medical and recreational drugs, can also influence fitness to dive, both for physiological and behavioural reasons. In some cases prescription drug use may have a net positive effect, when effectively treating an underlying condition, but frequently the side effects of effective medication may have undesirable influences on the fitness of diver, and most cases of recreational drug use result in an impaired fitness to dive, and a significantly increased risk of sub-optimal response to emergencies.

Formal educational prerequisites are variable. Diving skills are largely physical, but for professional diving a measure of literacy and numeracy is necessary to allow a reasonable chance of success with the theoretical knowledge requirements, and for effective on-site communication within the dive team. The international lingua franca of offshore diving operations is English.

Some training standards include an ability to swim as a prerequisite.[3]

Format

Diver training is a form of competency-based adult education that generally occurs at least partly in a formal training environment for the components specified by diver training standards and for which certification is issued.[6] There are also non-formal and informal aspects where certified divers extend their competence and experience by practicing the basic skills and learning other complementary skills in the field.[7][8]

Prior learning may be recognised where applicable and permitted by the training standard. This is typically done by assessment against the requirements of the standards using the same methods as in formal training programmes for safety-critical skills and knowledge, and by accepting verifiable evidence of experience, as in signed and witnessed logbook entries.[9]

Diving theory

_2%252C_explains_the_effects_of_pressure_on_the_inner.jpg.webp)

_1%252C_teaches_a_class_on_diving_related_casualty_care_to_Iraqi_navy_members_at_the_Iraqi_navy_school.jpg.webp)

Diving theory is the basic knowledge of the physical and physiological effects of the underwater environment on the diver.

Diving physics are the aspects of physics which directly affect the underwater diver and which explain the effects that divers and their equipment are subject to underwater which differ from the normal human experience out of water. These effects are mostly consequences of immersion in water, the hydrostatic pressure of depth and the effects of the pressure on breathing gases. An understanding of the physics is useful when considering the physiological effects of diving and the hazards and risks of diving.

Diving physiology is the physiological influences of the underwater environment on the physiology of air-breathing animals, and the adaptations to operating underwater, both during breath-hold dives and while breathing at ambient pressure from a suitable breathing gas supply. It, therefore, includes both the physiology of breath-hold diving in humans and other air-breathing animals, and the range of physiological effects generally limited to human ambient pressure divers either freediving or using underwater breathing apparatus. Several factors influence the diver, including immersion, exposure to the water, the limitations of breath-hold endurance, variations in ambient pressure, the effects of breathing gases at raised ambient pressure, effects caused by the use of breathing apparatus, and sensory impairment. All of these may affect diver performance and safety.[10]

Immersion affects fluid balance, circulation and work of breathing.[11][12] Exposure to cold water can result in the harmful cold shock response,[13][14] the helpful diving reflex and excessive loss of body heat.[15][16][17][18] Breath-hold duration is limited by oxygen reserves, and the risk of hypoxic blackout, which has a high associated risk of drowning.[19][20][21]

Large or sudden changes in ambient pressure have the potential for injury known as barotrauma.[10][22] Breathing under pressure involves several effects. Metabolically inactive gases are absorbed by the tissues and may have narcotic or other undesirable effects, and must be released slowly to avoid the formation of bubbles during decompression.[23] Metabolically active gases have a greater effect in proportion to their concentration, which is proportional to their partial pressure, which for contaminants is increased in proportion to absolute ambient pressure.[10]

Work of breathing is increased by increased density and viscosity of the breathing gas, artifacts of the breathing apparatus, and hydrostatic pressure variations due to posture in the water. The underwater environment also affects sensory input, which can impact on safety and the ability to function effectively at depth.[11]

Decompression theory is the study and modelling of the transfer of the inert gas component of breathing gases from the gas in the lungs to the tissues and back during exposure to variations in ambient pressure. In the case of underwater diving, this mostly involves ambient pressures greater than the local surface pressure,[24] but astronauts, high altitude mountaineers, and travellers in aircraft which are not pressurised to sea level pressure,[25][26] are generally exposed to ambient pressures less than standard sea level atmospheric pressure. In all cases, the symptoms caused by decompression occur during or within a relatively short period of minutes to hours, or occasionally days, after a significant pressure reduction.[24] The term "decompression" derives from the reduction in ambient pressure experienced by the organism and refers to both the reduction in pressure and the process of allowing dissolved inert gases to be eliminated from the tissues during and after this reduction in pressure. The uptake of gas by the tissues is in the dissolved state, and elimination also requires the gas to be dissolved, however a sufficient reduction in ambient pressure may cause bubble formation in the tissues, which can lead to tissue damage and the symptoms known as decompression sickness, and also delays the elimination of the gas.[24]

Decompression modeling attempts to explain and predict the mechanism of gas elimination and bubble formation within the organism during and after changes in ambient pressure,[27] and provides mathematical models which attempt to predict acceptably low risk and reasonably practicable procedures for decompression in the field.[28] Both deterministic and probabilistic models have been used, and are still in use.

Diving medicine, also called undersea and hyperbaric medicine (UHB), is the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of conditions caused by humans entering the underwater environment. It includes the effects on the body of pressure on gases, the diagnosis and treatment of conditions caused by marine hazards and how a diver's fitness to dive affects the diver's safety.

Hyperbaric medicine is a related field associated with diving, since recompression in a hyperbaric chamber is used as a treatment for two of the most significant diving-related illnesses, decompression sickness and arterial gas embolism.

Diving medicine deals with medical research on issues of diving, the prevention of diving disorders, treatment of diving accidents and diving fitness. The field includes the effect of breathing gases and their contaminants under high pressure on the human body and the relationship between the state of physical and psychological health of the diver and safety.

In diving accidents it is common for multiple disorders to occur together and interact with each other, both causatively and as complications.

Diving medicine is a branch of occupational medicine and sports medicine, and first aid for diving injuries an important part of diver education.

Teaching of diving theory is usually provided as classroom lecture sessions with formative assessment tasks and exercises and a written examination for final assessment. Blended learning is used by some agencies and schools to ensure a more consistent standard.

A working knowledge of the Diving environment in which the diver is likely to operate is necessary so that the diver can to some extent understand and predict the likely conditions they will experience while diving, and the associated hazards and risks. This knowledge is also necessary for informed consent in terms of health and safety legislation, and for diving supervisors, instructors, dive leaders and recreational divers it is essential for the assessment of the risk to which they or the people for whom they have a duty of care will be exposed while diving.

Dive planning

Dive planning is the practical application of theoretical knowledge and understanding. It is the process of planning an underwater diving operation. The purpose of dive planning is to increase the probability that a dive will be completed safely and the goals achieved.[29] Some form of planning is done for most underwater dives, but the complexity and detail considered may vary enormously.[30] In most professional diving, dive planning is mainly the responsibility of the supervisor, but the diver is expected to understand the process sufficiently to know when it has been done correctly. In recreational diving, unless under training, the diver is generally considered equally responsible for the planning of any dive they participate in, along with the other involved divers, so dive planning at the level of certification is an important aspect of recreational diver training.

Professional diving operations are usually formally planned and the plan documented as a legal record that due diligence has been done for health and safety purposes.[31][2] Recreational dive planning may be less formal, but for complex technical dives, can be as formal, detailed and extensive as most professional dive plans. A professional diving contractor will be constrained by the code of practice, standing orders or regulatory legislation covering a project or specific operations within a project, and is responsible for ensuring that the scope of work to be done is within the scope of the rules relevant to that work.[31] A recreational (including technical) diver or dive group is generally less constrained, but nevertheless is almost always restricted by some legislation, and often also the rules of the organisations to which the divers are affiliated.[30]

The planning of a diving operation may be simple or complex. In some cases the processes may have to be repeated several times before a satisfactory plan is achieved, and even then the plan may have to be modified on site to suit changed circumstances. The final product of the planning process may be formally documented or, in the case of recreational divers, an agreement on how the dive will be conducted. A diving project may consist of a number of related diving operations.[32]

A documented dive plan may contain elements from the following list:[29]

- Overview of Diving Activities

- Schedule of Diving Operations

- Specific Dive Plan Information

- Budget

For scuba dives, selection of the breathing gases and calculation of the required quantities is one of the most complex parts of dive planning, and is done in parallel with planning of the dive profile and decompression plan.

The general aspects of dive planning include the following, but not all of these apply to every dive, and in many cases there is no choice available to the diver, who must work within the constraints of what is available and appropriate to their level of competence. Planning of a complex dive may be an iterative process, and the order of steps may vary.[32][33][34][35]

- Purpose of the dive.

- Site analysis, environmental aspects and known hazards of the site and task.

- Selection of mode and techniques of diving. This aspect is often severely limited, and for training purposes is usually linked to the training standard.

- Selection of team.

- Estimation of depth and time, dive profile, decompression plan. These are generally constrained by the purpose and site.

- Choice of equipment.

- Gas planning for the planned profile, allowing for contingencies and foreseeable emergencies.

- Risk assessment is based on the planning to this point. The assessed risk must be acceptable if the dive is to be done. It may be possible to reduce an unacceptable risk by changing the plan.

- Contingency and emergency planning depend on the outcome of the risk assessment.

- Other logistical considerations, arranging permits and permission to dive, schedule of tasks and budgeting.

- Schedule of tasks and budget.

Teaching of dive planning typically omits any aspects not relevant to the certification level, and to some extent the certification will be defined by the competence requirements for dive planning. Assessment of dive planning competence is commonly a combination of written exams on the details, and direct observation of performance of dive planning tasks.

Other theory based knowledge

Professional divers are required to be familiar with the law regulating their occupation, and any national or international codes of practice that apply in the region where they will practice. National legislation will commonly be included in the curriculum for entry level professional diving, and may be recognised as prior learning for further diver training. The level of knowledge required of a diving supervisor is considerably higher, and is usually part of supervisor training and assessment.[36]

Occupational heath and safety are important aspects of professional diving. The diver is expected to understand the hazards, risks and potential consequences of diving at work and using the equipment provided in the environment of the project, and though risk assessment and team safety on the job are primarily the responsibility of the supervisor and the employer, the diver is also responsible as a member of the team and is expected to have sufficient knowledge of the processes and risks to reasonably accept the risk assessment.[35]

Diving skills

Diving skills can be grouped by skills relating to the mode of diving – freediving, scuba, surface supplied or saturation diving – and whether the skill is a standard skill used in everyday diving, an emergency skill to keep oneself alive when something goes wrong, or a rescue skill to be used in the attempt to assist another diver in difficulty.

Scuba skills are the skills required to dive safely using self-contained underwater breathing apparatus, (scuba). Most of these skills are relevant to both open circuit and rebreather scuba, and many are also relevant to surface-supplied diving. Those skills which are critical to the safety of the diver may require more practice than is usually provided during training to achieve reliable long-term proficiency[37]

Some of the skills are generally accepted by recreational diver certification agencies[38] as necessary for any scuba diver to be considered competent to dive without direct supervision, and others are more advanced, though some diver certification and accreditation organizations may consider some of these to also be essential for minimum acceptable entry level competence.[39] Divers are instructed and assessed on these skills during basic and advanced training, and are expected to remain competent at their level of certification, either by practice or refresher courses.

The skills include selection, functional testing, preparation and transport of scuba equipment, dive planning, preparation for a dive, kitting up for the dive, water entry, descent, breathing underwater, monitoring the dive profile (depth, time and decompression status), personal breathing gas management, situational awareness, communicating with the dive team, buoyancy and trim control, mobility in the water, ascent, emergency and rescue procedures, exit from the water, unkitting after the dive, cleaning and preparation of equipment for storage and recording the dive, within the scope of the diver's certification.[38][39][3][40] Some of these skills affect the diver's ability to minimise adverse environmental impact.[41][1]

Surface supplied diving skills are the skills and procedures required for the safe operation and use of surface-supplied diving equipment. Besides these skills, which may be categorised as standard operating procedures, emergency procedures and rescue procedures, there are the actual working skills required to do the job, and the procedures for safe operation of the work equipment other than diving equipment that may be needed.

Some of the skills are common to all types of surface-supplied equipment and deployment modes, others are specific to the type of bell or stage, or to saturation diving. There are other skills required of divers which apply to the surface support function, and some of those are also mentioned here.

Standard diving skills include skills like buoyancy control, finning, mask clearing, pre-dive checks and diver communications. They are used all the time, and are seldom lost due to lack of practice. Usually the diver gets better at these skills over time due to frequent repetition.

Emergency skills should seldom be needed, and may not be practiced often after training, but when an emergency occurs, the ability to perform the skill adequately, if not necessarily flawlessly, may be critical to the diver's health or survival.

Rescue skills are more relevant to keeping a co-worker alive than oneself. If lucky, a diver may never need to attempt the rescue of another, and these skills also need periodical scheduled repetition to retain competence. First aid skills are a similar category, and are generally re-assessed periodically to remain in date.[31] It is generally considered a responsibility of the employer to ensure that their employees get sufficient practice in emergency and rescue skills.

Training methods for diving skills

Diving skills are practical skills, suitable for learning by performing and improvement by correct repetition and overlearning. Many of the diving skills are safety-critical – incorrect performance can put the diver or another person at risk, and in some cases incorrect response can be rapidly fatal. The skill is generally discussed, demonstrated by a skilled practitioner, and then attempted by the learner in controlled conditions. Repetition with feedback from the instructor is generally continued until the skill can be performed reliably under normal conditions. Once mastered, the critical skills may be combined with related activities and practiced until they become second nature. Professional, particularly military training, may overtrain skills until they are internalised to the extent of being conditioned reflexes, requiring very little conscious thought, as adequate performance under highly stressed and task loaded conditions may be necessary for survival.[42]

Situations can develop during dives where external stress can distract the diver and hinder prompt and appropriate response. This can put the diver at immediate risk. Stress exposure training, which includes exercise of important existing skills in a stressful and distracting environment to develop the ability to perform them reliably in spite of the circumstances, can be used to prepare divers to function effectively under high-stress conditions. This is done after the diver has mastered the skills in a benign environment under conditions conducive to learning and retention of the skills. This form of training is generally not used in recreational diver training, and is more likely to be encountered in military and other professional diving,[43] and occasionally in technical diver training. It is not usually required by the training standards.[42]

Training venues for diving skills

_training._(49085148586).jpg.webp)

Initial skills training is restricted to confined water, a diving environment that is enclosed and bounded sufficiently for safe training purposes. This generally implies that conditions are not affected by geographic or weather conditions, and that divers can not get lost. Swimming pools and diver training tanks are included in this category. A diver training tank is a container of water large and deep enough to practice diving and underwater work skills, usually with a window through which the exercises can be viewed by the instructor. Once competence has been demonstrated in confined water, repetition of skills in open water is usual. This is generally done in combinations that simulate realistic circumstances when reasonably practicable.

First aid skills

Most professional divers are required by national or state legislation to be qualified first aid providers to a specified standard. First aid training is not generally considered to be an integral part of diver training, but may be provided in parallel. First aid registration is generally valid for a limited period and must be updated to stay in-date to dive. Most third party first aid training does not include specific first aid for diving injuries such as high concentration oxygen administration. This is generally additional to the standard first aid training.[3]

In recreational diving a first aid certification is needed for Rescue Diver and any certification for which Rescue Diver is a prerequisite, such as Divemaster and Instructor.

Underwater work skills

_2%252C_instructs_a_Barbados_Coast_Guard_diver_on_the_proper_way_to_use_a_hydraulic_grinder_underwater.jpg.webp)

Underwater work skills may be included in professional diver training to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the requirements of the relevant training standard, which will specify the minimum, and the diving school, which may choose to offer more than the minimum as a premium service.

Specialist work skills are generally not part of diver training, and are either learned at a specialist training facility, from the equipment manufacturer, or from the employer at the workplace.

Training methods vary depending on the specific skill, but in many cases it is more effective to first learn the skill out of the water, where it is generally safer and easier, and where immediate feedback on problems is much simpler, then learn how to do it in the underwater environment. Some work skills used underwater are more complex and difficult to learn than diving skills – it is quicker to train a skilled welder to dive well than to train a skilled diver to weld well. This principle holds particularly for professional skills. A marine scientist or archaeologist may require 3 to 5 years full-time university study to become competent in their chosen field, but can be trained to do the relevant diving in about a month.[3]

Competence assessment

For the diver, procedural knowledge – the knowledge of how to do things – is generally considered of greater importance than descriptive knowledge – the knowledge about things, which is more important to the instructor. This is generally indicated in the assessment criteria and tools for divers who must safely dive, and supervisors and instructors who already know how to dive safely, but must be able to recognise and assess the hazards of a specific dive plan and manage the dive or explain the hazards and procedures of diving and their possible consequences to the learner diver.

Competence may be assessed in several ways. Theoretical knowledge and understanding is often amenable to assessment by written examination, which has the advantage of inherently providing a permanent record. Practical skills are more generally assessed by direct observation of a demonstration of the skill, or by inference, where successful completion of an activity implies acceptable application of the skill. In some cases simulations are used, particularly for emergency skills. Records of practical assessment are usually in the form of a report made by the assessor, which may involve the use of a checklist to ensure that all aspects have been covered, and may also include video recordings.

The level of competence required depends on the safety implications of the skill. A qualified diver should be a low risk for causing injury or death to themselves or another member of the diving team when operating within the constraints of the training standard. Competence at the time of assessment is no guarantee of competence at a future date. Retention and improvement of skills requires practice.

Quality assurance

The quality assurance of diver training is usually based on three basic components:[6]

- Diver training standards – Documents which define the minimum levels of competence acceptable for a person to be registered as a diver against the specified standard. As a general rule, there will be a number of safety critical skills which must always be demonstrated as competent, and other skills and knowledge which require general competence, but where some leeway can be tolerated.

Training manuals, assessment tools, task descriptions, checklists and other documentation may be required as evidence that training complies with the standard.[6] - Audits – Periodical re-assessment of the competence of training staff and adequacy of staff, equipment, documentation and venues, by personnel authorised by the certification agency or registration authority. These requirements may be specified in the training standard or a code of practice or similar document provided by the certification or registration authority.[6]

- Records – Permanent records of attendance, assessments, completed tasks and other documentation specified by the training standard, code of practice or regulations may be required to be kept available for a specified period for inspection as evidence of adherence to standards. Samples of these would be checked during audits.[6]

Training standards

In some cases national diver training standards and codes of practice will apply to professional diver training, assessment and registration, for example:

- Australia: Australian Diver Accreditation Scheme (ADAS)

- Canada: Diver Certification Board of Canada (DCBC)

- Norway: Petroleum Safety Authority Norway (PSA)

- South Africa: Department of Employment and Labour (DEL)

- United Kingdom: Health and Safety Executive (HSE)

Diving schools

Diving schools are establishments where divers are trained and assessed. They range from a spare room in the home of a freelance recreational diving instructor, to a set of offices, classrooms, workshops, stores, accommodations and ancillary structures such as diving tanks, swimming pools, diving support vessels, saturation systems, hyperbaric chambers and similar, with associated staff and equipment, for a major military or commercial diving school. The minimum facilities for occupational diver training schools may be specified by a standard or code of practice, and in these cases the school may be periodically audited to ensure that the facilities comply with requirements.[6]

Professional divers

Professional divers are generally trained firstly to dive safely as a member of a dive team, and secondly in underwater work skills specific to their employment. Registration as a professional diver does not necessarily imply competence in any specific work skills other than those commonly required by the majority of professional diving work. These may be specified in the training standard associated with the specific registration, but training standards can change over time and the skills required for original registration may no longer correspond in all details to the current standard, particularly where equipment use in the industry has changed over time. A diver who has been consistently employed can be reasonably expected to remain up to date with industry developments, but there may be cases where divers and supervisors do not keep up with developments. Periodical competence assessment may be used as a way of keeping track of whether a diver is acceptably up-to-date in a specific skill set.[44]

Commercial divers

The training of commercial divers varies according to the legislative requirements of the country in which the diver will be registered. In several countries registration is through a government department or an NGO set up for the purpose. Some of these countries offer reciprocal recognition of diver qualification, allowing cross-border employment to divers with the relevant registration. Diver training is usually done through registered diving schools within the jurisdiction of the relevant government, and to standards promulgated by a government department or national standards body.[31][2]

Where there is no international recognition of divers registered by a foreign organisation, formal recognition of prior learning may be available through a registered diving school. This will often involve assessment to the same standards, often using the same assessment tools, as for the divers trained by the school. Formally logged records of diving experience may be recognised at face value, or may be verified by the assessing school.[31]

Military divers

Military diver training is generally provided by a specialist military diver training unit in one of the armed forces of the same country as the force that will employ the divers, often with further specialist training in the deployment unit, though there is also a history of training provision by allied forces. Military diver training is likely to include stress training, particularly for tactical divers, and may include registration allowing them to work as commercial divers after discharge.

United Kingdom

British Army and Royal Navy divers are trained at the Defence Diving School at Horsea Island, Plymouth. Officers and enlisted personnel do the same training, and get certified as HSE level 1 and 2 divers in addition to military qualification, which will allow them to work as commercial divers if they leave the military.[45][46]

Public safety divers

Depending on the jurisdiction, public safety divers may be required to be registered as commercial divers, or may be trained specifically as public safety divers by specialists, or may be initially trained as recreational divers, then given additional specialist training.[47][48]

In addition to basic diving skills training, public safety divers require specialized training for recognizing hazards, conducting risk assessments, search procedures, diving in zero visibility, using full-face masks with communication systems, and recovering evidence that is admissible in court. Some of the water they are required to dive in is contaminated, and they may be required to wear vulcanized drysuits, with diving helmets sealed to the suit, and utilize surface-supplied air. At times, the decontamination process that takes place out of the water can be longer than the dive time.[48]

Scientific divers

When a scientific diving operation is part of the duties of the diver as an employee, the operation may be considered a professional diving operation subject to regulation as such. In these cases the training and registration may follow the same requirements as for other professional divers, or may include training standards specifically intended for scientific diving. In other cases, where the divers are in full control of their own diving operation, including planning and safety, diving as volunteers, the occupational health and safety regulations may not apply.[31][49]

Where scientific diving is exempt from commercial diving regulation, training requirements may differ considerably, and in some cases basic scientific diver training and certification may not differ much from entry level recreational diver training.

Technological advances have made it possible for scientific divers to accomplish more on a dive, but they have also increased the complexity and the task loading of both the diving equipment and the work done, and consequently require higher levels of training and preparation to safely and effectively use this technology. It is preferable for effective learning and safety that such specialisation training is done systematically and under controlled conditions, rather than on site and on the job. Environmental conditions for training should include exercises in conditions as close as reasonably practicable to field conditions.[50]

International equivalence

The International Diving Regulators and Certifiers Forum[51] (IDRF) is a group of representatives of countries with national training standards for professional divers, who work together towards mutual recognition of diver registration and to identify and implement good practice in diver training and assessment.[52] Members of the IDRF include ADAS (Australia), DCBC (Canada), HSE (UK), PSA (Norway), and the Secretariat General to the Sea Progress Committee (France).

A similar arrangement for international recognition of scientific divers within Europe exists. Two levels of scientific diver registration are recognised by the European Scientific Diving Panel. These represent the minimum level of training and competence required to allow scientists to participate freely throughout the countries of the European Union in underwater research projects diving using scuba. Certification or registration by an authorized national agency is a prerequisite, and depth and breathing gas limitations may apply.[53]

- The European Scientific Diver (ESD) – A diver competent to perform as a member of a scientific diving team. – A diver competent to perform as a member of a scientific diving team.[54]

- The Advanced European Scientific Diver (AESD) – A diver competent to organise a scientific diving team – A diver competent to organise a scientific diving team.[54]

This competence may be gained either through a formal training program, by in the field training and experience under appropriate supervision, or by a combination of these methods.[54] These standards specify the minimum basic training and competence for scientific divers, and do not consider any speciality skill requirements by employers. Further training for job-specific competence is additional to the basic competence implied by the registration.[54]

Recreational divers

Recreational diver training is the process of developing knowledge and understanding of the basic principles, and the skills and procedures for the use of scuba equipment so that the diver is able to dive for recreational purposes with acceptable risk using the type of equipment and in similar conditions to those experienced during training. Most recreational diver training is for certification purposes, but a significant amount is for non-certification purposes such as introductory scuba experience, refresher training, and regional orientation.

Recreational scuba

Not only is the underwater environment hazardous but the diving equipment itself can be dangerous. There are problems that divers must learn to avoid and manage when they do occur. Divers need repeated practice and a gradual increase in challenge to develop and internalise the skills needed to control the equipment, to respond effectively if they encounter difficulties, and to build confidence in their equipment and themselves. Diver practical training starts with simple but essential procedures, and builds on them until complex procedures can be managed effectively. This may be broken up into several short training programmes, with certification issued for each stage,[55] or combined into a few more substantial programmes with certification issued when all the skills have been mastered.[56][57]

Many diver training organizations exist, throughout the world, offering diver training leading to certification: the issuing of a "Diving Certification Card," also known as a "C-card," or qualification card. This diving certification model originated at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1952 after two divers died while using university-owned equipment and the SIO instituted a system where a card was issued after training as evidence of competence.[58][59] Diving instructors affiliated to a diving certification agency may work independently or through a university, a dive club, a dive school or a dive shop. They will offer courses that should meet, or exceed, the standards of the certification organization that will certify the divers attending the course. The International Organization for Standardization has approved six recreational diving standards that may be implemented worldwide, and some of the standards developed by the (United States) RSTC are consistent with the applicable ISO Standards:[60]

The initial open water training for a person who is medically fit to dive and a reasonably competent swimmer is relatively short. Many dive shops in popular holiday locations offer courses intended to teach a novice to dive in a few days, which can be combined with diving on the vacation.[55] Other instructors and dive schools will provide more thorough training, which generally takes longer.[57] Dive operators, dive shops, and cylinder filling stations may refuse to allow uncertified people to dive with them, hire diving equipment or have their diving cylinders filled. This may be an agency standard, company policy, or specified by legislation.[61]

International standards equivalence

The International Organization for Standardization has approved six recreational diving standards that may be implemented worldwide (January 2007).

The listed standards developed by the (United States) RSTC are consistent with the applicable ISO Standards:[60]

| (USA) RSTC Standard | ISO Standard | Alternative ISO Title |

|---|---|---|

| Introductory Scuba Experience | No equivalent | |

| No equivalent | Level One Diver [62] | Supervised Diver |

| Open Water Diver | Level Two Diver[62] | Autonomous Diver |

| Dive Supervisor | Level Three Diver[62] | Dive Leader |

| Assistant Instructor | Level 1 Instructor[62] | |

| Scuba Instructor | Level 2 Instructor[62] | |

| Instructor Trainer | No equivalent | |

| No equivalent | Service Provider[62] |

Technical diving

Technical diving requires specialised equipment and training. There are many technical training organisations: see the Technical Diving section in the list of diver certification organizations. Technical Diving International (TDI), Global Underwater Explorers (GUE), Professional Scuba Association International (PSAI), International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD) and National Association of Underwater Instructors (NAUI) were popular as of 2009. Professional Technical and Recreational Diving (ProTec) joined in 1997. Recent entries into the market include Unified Team Diving (UTD), InnerSpace Explorers (ISE) and Diving Science and Technology (DSAT), the technical arm of Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI). The Scuba Schools International (SSI) Technical Diving Program (TechXR – Technical eXtended Range) was launched in 2005.[63]

British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC) training has always had a technical element to its higher qualifications, however, it has recently begun to introduce more technical level Skill Development Courses into all its training schemes by introducing technical awareness into its lowest level qualification of Ocean Diver, for example, and nitrox training will become mandatory. It has also recently introduced trimix qualifications and continues to develop closed circuit training.

Freediving

In most jurisdictions, no certification is required for freediving, and the equipment is sold freely over the counter with no questions asked of the purchaser's competence to use it. Most freedivers learn the skills from practice, often with some coaching from a friend, and sometimes attend a formal training programme presented by a qualified and registered instructor, with assessment and certification of competence as the target.[64]

Some recreational diver training agencies offer training and certification in freediving, sometimes known as a snorkel certificate.[65][66] Professional diver training standards may include freediving at basic level as part of scuba training and assessment.[3]

Training of diving support personnel

Professional diving support personnel are the members of the professional diving team, which at minimum includes a working diver, a standby diver and a supervisor:

- Diving supervisor – Professional diving team leader responsible for safety. Usually regulated by the same legislation as for professional divers. Diving supervisor candidates are generally selected from the pool of competent, reliable and experienced divers with leadership and management potential employed by a contractor to receive specialised additional training and assessment in dive planning, risk assessment, site management and emergency management by a commercial diving school.[36]

- Stand-by diver – A member of a dive team who is ready to assist or rescue the working diver. All professional divers are qualified to act as standby diver as part of their duties.[31][3]

- Bellman – The member of a dive team who acts as stand-by diver and tender from the diving bell. All divers qualified to dive from a bell are also qualified to act as bellman as part of their duties.[31]

- Chamber operator – A person who operates a diving chamber. May be regulated by the same legislation as for professional divers. Training and assessment will commonly be through a diving school, as chamber skills are part of diver training at some levels.[31]

- Diver's attendant – Assistant for a diver. Not usually a regulated occupation, but often the post is filled by another diver who is not required for diving at the time.[31]

- Life support technician – A member of a saturation diving team who operates the surface habitat. Usually regulated by the same legislation as for professional divers.[31] Training and assessment is likely to be at a commercial diving school which trains saturation divers, as they have the infrastructure at hand.

- Diving medical technician – Person trained in advanced first aid for divers. Usually regulated by the same legislation as for professional paramedics, but may not be legal for practice within national territory.

- Diving instructor – Person who trains and assesses underwater divers. Usually regulated by the same legislation as for professional divers. Diving instructor candidates are generally selected from the supervisors employed by a diving school who have shown a high level of understanding of diving theory and practice, and the ability to teach. They are given further training in adult and occupational education, before the school can apply for registration for the instructor candidate.[31]

Recreational diving support may only be one person, but can be more:

- Dive leader, also known as Divemaster – Recreational diving certification and role. Similar to recreational diving certification systems, but may require membership and registration with the certification organisation.[67][68]

- Diving instructor – Person who trains and assesses underwater divers. Similar to recreational diving certification systems, but requires membership and registration with the certification organisation. Cross-over training is usually available, and multiple certification and membership is common. Instructor training is generally a relatively intensive program run by a diving instructor registered by the training agency as a course director, or some similar title. The training programmes tend to have titles like "Instructor Development Course" (PADI) or "Instructor Training Course" (NAUI).[69][70][71]

- Dive boat skipper – Person in command of a dive boat. Varies with national legislation. In some countries there is no specific requirement, in others there may be regulation, and it may vary between professional and recreational skippers, where a professional skipper may be considered as having a duty of care to clients or fellow employees.[72][73]

- Dive buddy – Diver accompanying another diver in a reciprocal assistance arrangement. Recreational divers are expected to act as in-water standby divers to their dive buddies on a reciprocity system: Each diver should be capable of assisting their buddy in any reasonably predictable contingency that may occur on the planned dive. Standard recreational diver training includes some assistance skills relevant to the expected range of contingencies that may be experienced by divers who dive within the limitations specified in their certification, at the skill level indicated by their certification, and under conditions in which they have appropriate experience, assuming that not too much competence has been lost due to lack of practice in the relevant skills, and that both divers follow the recommended procedures. This system can work very well when the dive buddies are familiar with each other's equipment, skills and behaviour, and have prepared for the dive effectively.

- Rescue diver – Recreational scuba certification emphasising emergency response and diver rescue. Rescue diver training provides the recreational diver with some of the assistance skills provided as standard in most professional entry-level diver training. These may include basic first aid with CPR, emergency oxygen administration for diving accidents, and managing a panicked or unresponsive diver underwater or at the surface. One or more rescue divers may be part of the surface support team for a major technical dive, but mostly the training is a prerequisite for divemaster and instructor training.

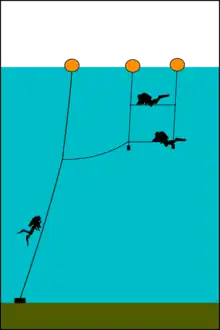

- Support diver – A diver who acts in support of a technical dive team or a record attempt. The support diver is an informal equivalent of a stand-by diver, with a role specific to the dive, which may include availability to assist in case of an emergency, transport decompression gases to divers in the water, carry messages between divers and the surface group. A support diver will usually have rescue diver certification, and whatever other certification is appropriate to the depth and environment of the part of the dive they will support. Complex and high-risk expeditions may use several support divers for the various stages of the dives. There is no specific training for this role.

Support personnel who are not generally part of the dive team, and apply similarly to professional and recreational diving, include:

- Compressor operator – Person who operates a diving air compressor. Most professional divers are trained in the operation of high pressure breathing air compressors within the scope of diving operations, but may not be legally competent to operate the same equipment as a vendor. Surface-supplied divers are generally trained in the operation of low pressure diving air compressors, but this is not specifically a diving skill, and a competent non-diver may be employed in this role.

- Gas blender – Person who blends breathing gas mixtures for scuba diving and fills diving cylinders. Recreational (technical) diving gas blenders may be trained and certified by a recreational diver training agency. This does not necessarily indicate legal competence to blend gas or to fill for other people, particularly in a commercial environment.[74] Recreational mixed gas users are generally trained to analyse the gases they may use for diving within the scope of their diving certification, but blending is beyond this scope.

- Diving equipment technician, also known as diving systems technician – Person who maintains, repairs and tests diving and support equipment. Equipment technicians are generally primarily trained as mechanical or electrical engineering technicians, with specialisation training in specific diving equipment. The technician training is usually through a regular trade school, technical college or similar establishment, and the specialisation training is generally through training courses and workshops run by the equipment manufacturers or their agents. There are also some training courses run by commercial diving schools which cover a range of skills for maintenance and repair of commonly used and generic diving and support equipment.

In all three of these cases requirements vary with national legislation. In some countries there is no specific requirement, in others some form of assessed competency may be necessary. Equipment technicians often have some equipment specific training from the equipment manufacturers, but the fundamental skill level required may vary considerably, and may depend on the specific types of equipment the technician is qualified to service, repair and inspect.

References

- 1 2 Johansen, Kelsey (2013). "Education and training". In Musa, Ghazali; Dimmock, Kay (eds.). Scuba Diving Tourism: Contemporary Geographies of Leisure, Tourism and Mobility. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-32494-9.

- 1 2 3 Staff (1977). "The Diving at Work Regulations 1997". Statutory Instruments 1997 No. 2776 Health and Safety. Kew, Richmond, Surrey: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (HMSO). Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Diving Advisory Board (2007). Class IV Training Standard (Revision 5.03 October 2007 ed.). South African Department of Labour.

- 1 2 3 4 "Occupational vs Recreational Diving". adas.org.au. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ↑ Williams, G.; Elliott, D.H.; Walker, R.; Gorman, D.F.; Haller, V. (2001). "Fitness to dive: Panel discussion with audience participation". Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. 31 (3). Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Diving Advisory Board (2007). Code of Practice for Commercial Diver Training, Revision 3 (PDF). Pretoria: South African Department of Labour. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- ↑ "IMCA Competence Assessment Portfolio" (PDF). London, UK: International Marine Contractors' Association. December 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ↑ " "Freelance Competence assessment e-portfolios". London, UK: International Marine Contractors' Association. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ↑ "Competence assessment of experienced surface supplied divers". London, UK: International Marine Contractors' Association. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 US Navy Diving Manual, 6th revision. United States: US Naval Sea Systems Command. 2006. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- 1 2 Pendergast, D.R.; Lundgren, C.E.G. (1 January 2009). "The underwater environment: cardiopulmonary, thermal, and energetic demands". Journal of Applied Physiology. 106 (1): 276–283. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.90984.2008. ISSN 1522-1601. PMID 19036887. S2CID 2600072.

- ↑ Kollias, James; Van Derveer, Dena; Dorchak, Karen J.; Greenleaf, John E. (February 1976). "Physiologic responses to water immersion in man: A compendium of research" (PDF). Nasa Technical Memorandum X-3308. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics And Space Administration. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ↑ Staff. "4 Phases of Cold Water Immersion". Beyond Cold Water Bootcamp. Canadian Safe Boating Council. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ "Exercise in the Cold: Part II – A physiological trip through cold water exposure". The science of sport. www.sportsscientists.com. 29 January 2008. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ↑ Lindholm, Peter; Lundgren, Claes E.G. (1 January 2009). "The physiology and pathophysiology of human breath-hold diving". Journal of Applied Physiology. 106 (1): 284–292. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.90991.2008. PMID 18974367. S2CID 6379788.

- ↑ Panneton, W. Michael (2013). "The Mammalian Diving Response: An Enigmatic Reflex to Preserve Life?". Physiology. 28 (5): 284–297. doi:10.1152/physiol.00020.2013. PMC 3768097. PMID 23997188.

- ↑ Sterba, J.A. (1990). "Field Management of Accidental Hypothermia during Diving". US Navy Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-1-90. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Cheung, S.S.; Montie, D.L.; White, M.D.; Behm, D. (September 2003). "Changes in manual dexterity following short-term hand and forearm immersion in 10 degrees C water". Aviat Space Environ Med. 74 (9): 990–3. PMID 14503680. Retrieved 11 June 2008.

- ↑ Pearn, John H.; Franklin, Richard C.; Peden, Amy E. (2015). "Hypoxic Blackout: Diagnosis, Risks, and Prevention". International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education. 9 (3): 342–347. doi:10.25035/ijare.09.03.09 – via ScholarWorks@BGSU.

- ↑ Edmonds, C. (1968). "Shallow Water Blackout". Royal Australian Navy, School of Underwater Medicine. RANSUM-8-68. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Lindholm, P.; Pollock, N.W.; Lundgren, C.E.G., eds. (2006). Breath-hold diving. Proceedings of the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society/Divers Alert Network 2006 June 20–21 Workshop. Durham, NC: Divers Alert Network. ISBN 978-1-930536-36-4. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Brubakk, A. O.; Neuman, T. S. (2003). Bennett and Elliott's physiology and medicine of diving (5th Rev ed.). United States: Saunders Ltd. p. 800. ISBN 978-0-7020-2571-6.

- ↑ Bauer, Ralph W.; Way, Robert O. (1970). "Relative narcotic potencies of hydrogen, helium, nitrogen, and their mixtures".

- 1 2 3 US Navy (2008). US Navy Diving Manual, 6th revision. United States: US Naval Sea Systems Command. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ↑ Van Liew, H.D.; Conkin, J. (2007). A start toward micronucleus-based decompression models:Altitude decompression. Annual Scientific Meeting, 14–16 June 2007. Ritz-Carlton Kapalua Maui, Hawaii: Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society, Inc. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "Altitude-induced Decompression Sickness" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Gorman, Des. "Decompression theory" (PDF). Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ↑ Wienke, B.R. "Decompression theory" (PDF). Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- 1 2 NOAA Diving Program (U.S.) (28 Feb 2001). Joiner, James T. (ed.). NOAA Diving Manual, Diving for Science and Technology (4th ed.). Silver Spring, Maryland: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, National Undersea Research Program. ISBN 978-0-941332-70-5. CD-ROM prepared and distributed by the National Technical Information Service (NTIS)in partnership with NOAA and Best Publishing Company

- 1 2 Gurr, Kevin (August 2008). "13: Operational safety". In Mount, Tom; Dituri, Joseph (eds.). Exploration and Mixed Gas Diving Encyclopedia (1st ed.). Miami Shores, Florida: International Association of Nitrox Divers. pp. 165–180. ISBN 978-0-915539-10-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Diving Regulations 2009". Occupational Health and Safety Act 85 of 1993 – Regulations and Notices – Government Notice R41. Pretoria: Government Printer. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 3 November 2016 – via Southern African Legal Information Institute.

- 1 2 Southwood, Peter (2010). Supervisor's Manual for Scientific Diving: SA Commercial diving to Codes of Practice for Inshore and Scientific Diving on SCUBA and SSDE. Vol. 1: Logistics and Planning. Cape Town: Southern Underwater Research Group.

- ↑ Mount, Tom (August 2008). "11: Dive Planning". In Mount, Tom; Dituri, Joseph (eds.). Exploration and Mixed Gas Diving Encyclopedia (1st ed.). Miami Shores, Florida: International Association of Nitrox Divers. pp. 113–158. ISBN 978-0-915539-10-9.

- ↑ Staff (2002). Williams, Paul (ed.). The Diving Supervisor's Manual (IMCA D 022 May 2000, incorporating the May 2002 erratum ed.). London, UK: International Marine Contractors' Association. ISBN 978-1-903513-00-2.

- 1 2 Diving Advisory Board (10 November 2017). NO. 1235 Occupational Health and Safety Act, 1993: Diving regulations: Inclusion of code of practice inshore diving 41237. Code of Practice Inshore Diving (PDF). Department of Labour, Republic of South Africa. pp. 72–139.

- 1 2 Diving Advisory Board (October 2007). Class IV Supervisor Training Standard. South African Department of Labour.

- ↑ Egstrom, G.H. (1992). "Emergency air sharing". Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society. Archived from the original on December 18, 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 "Minimum course standard for Open Water Diver training" (PDF). World Recreational Scuba Training Council. World Recreational Scuba Training Council. 1 October 2004. pp. 8–9. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- 1 2 "International Diver Training Certification: Diver Training Standards, Revision 4" (PDF). International Diving Schools Association. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ British Sub-Aqua Club (1987). Safety and Rescue for Divers. London: Stanley Paul. ISBN 978-0-09-171520-5.

- ↑ Hammerton, Zan (2014). SCUBA-diver impacts and management strategies for subtropical marine protected areas (Thesis). Southern Cross University.

- 1 2 Driskell, James E.; Johnston, Joan H. (1998). "Stress Exposure Training" (PDF). In Cannon-Bowers, Janis A.; Salas, Eduardo (eds.). Making decisions under stress: Implications for individual and team training. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10278-000. ISBN 1-55798-525-1.

- ↑ Robson, Sean; Manacapilli, Thomas (2014). Enhancing Performance Under Stress (PDF) (Report). RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0-8330-7844-5.

- ↑ Marine Division (January 2018). Guidance on Competence Assurance and Assessment: IMCA C 002 (Rev. 3 ed.). IMCA.

- ↑ "Defence Diving School". www.royalnavy.mod.uk. Royal Navy. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ "British Army Military Diver Training". bootcampmilitaryfitnessinstitute.com. 19 October 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ Phillips, Mark (November 2015). "Public Safety Diving and OSHA, Are We Exempt? Final Answer" (PDF). PS Diver Magazine. Mark Phillips. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- 1 2 Robinson, Blades (2 January 2011). "What is public safety diving". Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ↑ Diving Advisory Board. Code Of Practice for Scientific Diving (PDF). Pretoria: The South African Department of Labour. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Somers, Lee H. (1987). Lang, Michael A.; Mitchell, Charles T. (eds.). Training scientific divers for work in cold water and polar environments. Proceedings of special session on coldwater diving. Costa Mesa, California: American Academy of Underwater sciences. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "Minutes of the EDTC meeting held on Sept 10th 2010 in Prague, Czech Republic". The European Diving Technology Committee. 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ staff (2017). Closed Bell Diver Training V1.0 (Report). International Diving Regulators and Certifiers Forum (IDRCF).

- ↑ "European competency levels for scientific diving" (PDF). Retrieved 22 November 2018 – via UK Scientific Diving Supervisory Committee.

- 1 2 3 4 "Standards for European Scientific Divers (ESD) and Advanced European Scientific Divers (AESD)" (PDF). Workshop of the interim European Scientific Diving Committee. Banyuls-sur-mer, France: European Scientific Diving Committee. 24 October 2000. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- 1 2 PADI (2010). PADI Instructor Manual. Rancho Santa Margarita, CA: USA: PADI.

- ↑ "C.M.A.S. Diver Training Program" (PDF). Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques. 18 January 2005. pp. 4, 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- 1 2 Staff (2011). "1.2 Training Philosophy". General Training Standards, Policies, and Procedures. Version 6.2. Global Underwater Explorers.

- ↑ Manual for Diving Safety (PDF) (11th ed.). San Diego: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California. 2005. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-26.

- ↑ "Scripps Institution of Oceanography Diver Certification". SIO. 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-12-13.

- 1 2 "ISO approves 6 Diving Standards". World Recreational Scuba Training Council. 2013. Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ "Recreational diving Act, 1979" (in Hebrew). Knesset. 1979. Retrieved 16 November 2016 – via WikiSource.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Staff. "Standards for Training Organisations/System". EUF Certification International. Retrieved 28 September 2013.

- ↑ "SSI TechXR – Technical diving program". Scuba Schools International. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ↑ "Freediving professional". www.divessi.com. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ "One Star Snorkel Diver Training Programme". www.cmas.org. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ "Snorkeling Instructor". www.divessi.com. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ↑ Staff. "Competencies and qualifications of recreational scuba divers Level 1-3". EUF Certification. European Underwater Federation (EUF). Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- ↑ Staff. "Recreational diving services – Requirements for the training of recreational scuba divers – Part 3: Level 3 – Dive leader (ISO 24801-3:2014)". ISO. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ "ISO 24802-2:2014(en) Recreational diving services – Requirements for the training of scuba instructors – Part 2: Level 2". ISO. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ↑ "ISO 24802-1:2014(en), Recreational diving services – Requirements for the training of scuba instructors – Part 1: Level 1". ISO. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ↑ "Competencies and qualifications of scuba instructors". EUF Certification. European Underwater Federation (EUF). Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- ↑ Operations – Seafarer Certification Guidance Note: SA Maritime Qualifications Code: Small Vessel Code GOP-536.01 (PDF) (Revision No 5 ed.). South African Maritime Safety Authority. 21 January 2015.

- ↑ "10.4 Additional Endorsements to national certification 10.4.1 Commercial Dive skipper endorsement" (PDF). Marine Notice No. 13 of 2011 (Amended for Training Purposes: Small Vessel Examiners). South African Maritime Safety Authority.

- ↑ South African National Standard SANS 10019:2008 Transportable containers for compressed, dissolved and liquefied gases – Basic design, manufacture, use and maintenance (6th ed.). Pretoria, South Africa: Standards South Africa. 2008. ISBN 978-0-626-19228-0.