Eretnid dynasty | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1335–1381 | |||||||||||||||

The Eretnids under Eretna | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Sultanate | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Sivas and Kayseri | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||

• 1335–1352 | ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Eretna | ||||||||||||||

• 1352–1366 | Ghiyāth al-Dīn Muhammad I | ||||||||||||||

• 1366–1380 | ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn 'Ali | ||||||||||||||

• 1380–1381 | Muḥammad II Chelebī | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

• Established | 1335 | ||||||||||||||

• Independence | 1343 | ||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1381 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

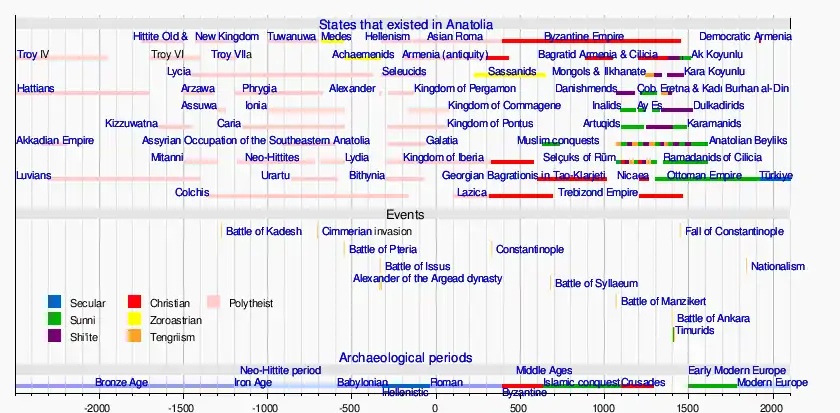

| History of Turkey |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Eretnid dynasty (Turkish: Eretna Beyliği) was a dynasty that ruled a sultanate spanning central and eastern Anatolia. The dynasty's founder, Eretna, was an Ilkhanid officer of Uyghur origin, under Tīmūrtāsh, who was appointed as the governor of Anatolia. Some time after the latter’s downfall, Eretna became the governor under the suzerainty of the Jalayirid ruler Hasan Buzurg. After an unexpected victory at the Battle of Karanbük, against Mongol warlords competing to restore the Ilkhanate, Eretna declared himself as the sultan of his domains. His reign was largely prosperous earning him the nickname Köse Peyghamber (lit. 'the beardless prophet').

Eretna's son Ghiyāth al-Dīn Muḥammad I, although initially preferred over his older brother Jafar, struggled to maintain his authority over the state and was quickly deposed by Jafar. Shortly after, he managed to restore his throne, although he could not prevent some portion of his territories from getting annexed by local Turkoman lords, the Dulkadirids, and the Ottomans. In 1365, when he had recently put an end to his vizier's revolt, he was murdered by his emirs in Kayseri, the capital.

His 13-year-old son, ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlī, was largely not allowed to interfere in administrative matters by the local emirs, who have been enjoying a substantial degree of autonomy since Eretna's demise. ʿAlī lacked necessary skills of governance and was described to have only cared for personal pleasures. The state's borders continued to shrink, and the capital temporarily came under Karamanid control. Kadi Burhan al-Din rose to power as the new vizier and further dispatched ʿAlī to command several largely unsuccessful campaigns. 'Ali died of the plague in August 1380 amidst one of those expeditions. The fourth Eretnid sultan, Muḥammad II Chelebī was 7 years old when his father died. His regent Burhan al-Dīn toppled him in less than a year and proclaimed himself as the new sultan by January 1381, ending the Eretnid dynasty's political presence.

There is a scant number of surviving buildings and literary works identified with the rule of the Eretnids. This contrasts with the neighboring contemporary states, who left a greater legacy of structures.

History

Background

The Ilkhanate emerged in West Asia under Hulagu Khan as part of the division of the Mongol Empire. After half a century, the seventh Ilkhān Ghazan's death marked the height of the state, and while his brother Öljaitü was capable of maintaining the empire, his conversion to Shiism sped up the impending fall and civil war in the region.[1]

.jpg.webp)

Eretna (1335–1352)

Of Uyghur stock,[2] Eretna was born to Jafar[3] or Taiju Bakhshi, a trusted follower of the second Ilkhanid ruler Abaqa Khan, and his wife Tükälti.[4] His name Eretna is popularly explained to have originated from the Sanskrit word ratna (रत्न) meaning 'jewel'.[5] This name was common among the Uyghurs following the spread of Buddhism,[6] and Eretna may have come from Buddhist parentage.[7]

Service under the Ilkhanate and Viceroy of Anatolia (1335–1343)

Eretna migrated to Anatolia following his brothers' execution due to a rebellion they joined,[8] and his master Tīmūrtāsh's appointment as the Ilkhanid governor of the region by Ilkhān Abū Saʿīd[6] and Chupan.[9] Eretna's master Tīmūrtāsh eventually rebelled against the Ilkhanate in 1323,[9] during which Eretna went into hiding.[6] However, the Ilkhān's weak authority and Tīmūrtāsh's father Chupan's influence over the state led to the pardoning of Tīmūrtāsh and the restoration of his position as the governor of Anatolia. He later led an extensive series of campaigns against the Turkoman emirates in Anatolia.[9] Upon the news of his brother Demasq Kaja's death on 24 August 1327, Tīmūrtāsh retreated to Kayseri,[10] and following his father's death, he fled to Mamluk Egypt in December while also planning to come into terms with Abū Saʿīd.[11] He was later killed on the orders of the Mamluk sultan.[9] Fearing punishment during Tīmūrtāsh's absence, Eretna took refuge in the court of Badr al-Dīn Beg of Karaman.[12] Tīmūrtāsh was replaced by Emir Muhammad from the Oirat tribe, who was the uncle of Abū Saʿīd.[13]

Eretna was later involved in a plot against the Ilkhān in 1334 but received a pardon and returned to Anatolia from the Ilkhanid court in Iran.[11] With Abū Saʿīd's death in 1335, the Ilkhanid period practically came to an end, leaving its place to continuous wars between several warlords from princely houses, namely the Chobanids and Jalayirids.[1] Back west, Eretna came under the suzerainty of the Jalayirid viceroy of Anatolia, Hasan Buzurg[6] but had already established his supremacy in the region to a considerable degree.[11] Hasan Buzurg left Eretna as his deputy in Anatolia when he departed east to oppose the Oirat chieftain Ali Padishah's attempt to occupy the throne. Eretna was officially appointed as the governor of Anatolia by Hasan Buzurg following his victory against Ali Padishah.[10] However, Hassan Kuchak rose in the Ilkhanid domains quickly in 1338.[14] Hassan Kuchak was the son of Tīmūrtāsh and had effectively become the pretender of his father's legacy. He defeated the Jalayirids near Aladağ and pillaged Erzincan.[15]

Due to constant upheavals in the east, Eretna forged an alliance with Mamluks, who confirmed him as the "Mamluk governor of Anatolia." On the contrary, Eretna did very little to uphold Mamluk sovereignty, minting coins on behalf of the new Chobanid puppet Suleiman Khan in 1339. Thus, the Mamluks started viewing the rising Turkoman leader Zayn al-Dīn Qarāja of Dulkadir more favorably. Eretna had already lost Elbistan to Qarāja in 1337–8 as well as Darende the next year. Having been robbed of the wealth he had stored in the latter city, Eretna confronted the Mamluk sultan, who brought up his failure to declare Mamluk sovereignty. In return, Eretna finally minted coins for the Mamluks in 1339–40. Still, Eretna was able to gain control of Sivas and Konya from the Karamanids.[16]

Eretna's attempt to be on good terms with the Chobanids was hindered by Hasan Kuchak's capture of Erzurum and siege of Avnik. He still insisted on his obedience to Suleiman Khan, although by 1341, he had gained enough power to be able to issue his coins.[17] 1341 is regarded by some scholars as the year he first declared his independence as it was when he first used the title sultan in his coins. Though, he sent his ambassadors to the new Mamluk sultan to secure his status as a na'ib. This elicited a new expedition by Hasan Kuchak in Eretna's lands.[18][19]

Choosing to stay in Tabriz, Hasan Kuchak dispatched his army to Anatolia under Suleiman Khan's command. The battle took place in the plain of Karanbük (between Sivas and Erzincan) in September–October 1343. Eretna initially faced a defeat but was able to flank Suleiman Khan and his guards. The Chobanid army disintegrated when Suleiman Khan fled the scene. Eretna's victory was unexpected for most actors in the region.[20] This victory resulted in the Eretnid annexation of Erzincan and several cities further east, also marking the beginning of Eretna's independent reign.[21] Hasan Kuchak's death at the hands of his wife prevented any retaliation for his earlier victory.[22]

Independent reign (1343–1352)

After the battle and Hasan Kuchak's death, Eretna assumed the title sultan, dispersed coins in his name, and formally declared sovereignty as part of the khutbah. He took the laqab Alāʾ al-Dīn,[23] which was attested in Ibn Battuta's Rihla and his coins.[24] Eretna additionally expanded his borders beyond Erzurum.[23] He faced a reduced number of threats to his rule in this period: Despite the intentions of the new Chobanid ruler Malek Ashraf to wage a war against him, such an expedition never came to be. The political vacuum in Mamluk Egypt, following Al-Nasir Muhammad's death, allowed Eretna to take Darende from them. And the Dulkadirid ruler Qarāja's focus in pillaging the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and tensions with the Mamluk emirs also made an attack from south unlikely.[25] Eretna further took advantage of the Karamanid ruler Ahmed's death in 1350, capturing Konya. Overall, Eretna's realm extended from Konya to Ankara and Erzurum,[26] also incorporating Kayseri, Amasya, Tokat, Çorum, Develi, Karahisar, Zile, Canik, Ürgüp, Niğde, Aksaray, Erzincan, Şebinkarahisar, and Darende,[27] with the capital initially situated in Sivas and later Kayseri.[3]

Eretna benefited from the support of the significant population of Mongol tribes in Central Anatolia (referred to as Qarā Tātārs in sources) in asserting his rule. He thus highlighted his succession to the Mongol tradition despite his Uyghur origin.[28] When he stopped referring to an overlord after 1341–2 and issued his own coins, he utilized the Uyghur script, which was also used for Mongolian,[29] to underline the Mongol heritage he sought to represent.[30] Eretna's identification with the Mongol tradition and repudiation of Mamluk sovereignty is in parallel with the overall character of medieval Anatolian rulers, who often experimented with various methods of claiming legitimacy in an atmosphere in which long-standing concepts of legitimacy were ceasing to exist.[31] Still, instead of the Mongols, who were numerous in the region from Kütahya to Sivas, Eretna appointed mamluks and local Turks in administrative positions fearing the rebirth of the Mongol rule.[32]

Eretna was a fluent Arabic-speaker according to Ibn Battuta[31] and was considered a scholar among the scholars of his era. He was famously known as Köse Peyghamber (lit. 'the beardless prophet') by his subjects who looked upon him favorably because his rule preserved order in a region that was politically crumbling apart.[6] He promoted and reinforced the sharia law in his domains and showed an effort to respect and sustain the ulama, sayyids, and sheikhs. An exception to the praise he received was al-Maqrizi's accusation that he allowed the state to later fall apart.[33]

Muḥammad I (1352–1365)

Muḥammad was liked by most Eretnid emirs, and upon his father's death, Eretna's vizier Khoja Ali secretly invited Muḥammad to Kayseri to become the new sultan, although Muḥammad's older brother Jafar was already residing there. Jafar was imprisoned by Muḥammad for some time, but he eventually escaped to Egypt. However, Muḥammad's rule did not fare well as he behaved debaucherously and treated his siblings unfairly. Since he was young, authority came into the hands of his emirs.[34] Turkoman tribes took control of the region of Canik.[35] Although the Dulkadirids to the south expanded their borders at the expense of the Eretnids, the Dulkadirid beg Zayn al-Dīn Qarāja would soon seek protection in Muḥammad's court fleeing from the Mamluks, who were preparing to prosecute him for the rebellion he led. On 22 September 1353, Muḥammad deported Qarāja to Mamluk-controlled Aleppo in exchange for a payment of 500 thousand dinars by the Mamluks, who would later transport Qarāja to Cairo for his execution.[36] This did not affect the fate of Muḥammad, as he was deposed by his emirs, and his half-brother Jafar reigned for a year.[34]

After losing the throne to his half-brother, Muḥammad fled to Konya[34] taking refuge amongst the Karamanids[27] and later Sivas. The governor of Sivas, Ibn Kurd, recognized him and assisted him in the restoration of his rule.[34] In April 1355, he faced Jafar at the Battle of Yalnızgöz.[27] He came to terms with the vizier Ali Khoja and killed Jafar, reclaiming his rule.[34] In 1361, as a reprisal to a raid by Tatars of the Chavdar tribe, Ottoman Beg Murad I captured Ankara Castle from the Eretnids. Muḥammad allied himself with the Dulkadirids in September 1362 in a joint campaign to drive the Mamluks away from Malatya. Mamluk governor of Damascus, Yalbugha and his 24 thousand-strong force marched north and raided Eretnid and Dulkadirid lands. However, this effort failed to regain Mamluk control.[37]

In 1364, Khoja Ali Shah led an uprising against Muḥammad and marched towards Kayseri. Muḥammad was defeated and had to request assistance from the Mamluk Sultan Al-Kamil Sha'ban. Upon a decree by the Mamluk Sultan, the governor of Aleppo sent his forces to aid Muḥammad, with which he subdued and executed Khoja Ali Shah in 1365. Soon after, other emirs who wanted to preserve their autonomy, such as Hajji Shadgeldi and Hajji Ibrahim,[27] killed Muḥammad in Kayseri before he could reinforce his authority, enthroning his son Ali.[38] Around that time, the eastern part of the realm, including Erzincan, Erzurum, and Bayburt, had come under the rule of a local figure, Ahi Ayna.[39]

'Ali (1366–1380)

'Ali was crowned at 13 years old, following the murder of his father.[40] After Muḥammad's death, local emirs obtained control of much of the region with the former vizier Khoja Ali Shah's son Hajji Ibrahim in Sivas, Sheikh Najib in Tokat, and Hajji Shadgeldi Pasha in Amasya. The Karamanids invaded Niğde and Aksaray, and local Mongol tribes started disrupting the public order.[41] ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn 'Ali was particularly known to have solely cared for pleasure[6] and lacked the skills to consolidate his authority. He was largely disregarded in political matters.[42]

In 1375, when 'Ali was in the midst of a feast in his hammam in Kayseri, Karamanids captured the city with the help of the Mongol tribes of Samargar and Chaykazan, prompting 'Ali to flee to Sivas. Statesman Kadi Burhan al-Din tried to fend off the Karamanids with the hopes that he could claim Kayseri for himself. He wasn't successful, getting arrested when 'Ali uncovered his true intentions.[42] In addition, the Dulkadirids gained control of Pınarbaşı.[40] The Emir of Sivas, Hajji Ibrahim, who allied with the leader of Samargar, Hizir Beg, rescued Burhan al-Din and imprisoned 'Ali instead.[43] Hajji Ibrahim further appointed Hizir Beg as the governor of Kayseri and kept 'Ali in isolation in Sivas. Although 'Ali was released for a brief period of time, 'Ali was imprisoned once again by Hajji Mukbil, who was the mamluk of the recently-deceased Hajji Ibrahim.[44] 'Ali was liberated by Burhan al-Din in 1378. In June of that year, Burhan al-Din was made vizier by the emirs to prevent a possible revolt of peasants disgruntled by 'Ali's incompetence.[45]

Kadi Burhan al-Din later dispatched 'Ali to lead several campaigns. One was aimed at subduing Burhan al-Din's rival Hajji Shadgeldi of Amasya, but this proved to be futile and further reinforced Shadgeldi's influence over the region. Another expedition consisted of efforts to reclaim Niğde, which was largely fruitless except for Karahisar's capture. After raiding the Turkomans near Niğde in 1379, 'Ali took advantage of the death of Pir Husayn Beg, the emir of Erzincan, through a campaign to retake the city, which was also unsuccessful. Alāʾ al-Dīn 'Ali died in Kazova in August 1380 from the plague amidst another attempt to crush Shadgeldi.[45] His body was transferred to Tokat and then to Kayseri. He was buried in Köşkmedrese beside his father and grandfather.[46]

Muḥammad II Chelebī and usurpation by Kadi Burhan al-Din

Muḥammad II Chelebī was crowned when he was 7 years old, after his father, ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn 'Ali died in August 1380 from the plague.[47] His regent was Kadi Burhan al-Din, who proclaimed himself as the ruler by January 1381. According to Ibn Khaldun and Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani, Muhammad was killed by Kadi Burhan al-Din in 1390.[48]

Culture

Architecture

There are no surviving mosques, madrasas, caravanserais, hospitals, or bridges dated back to Eretna's rule, except for tombs. This contrasts with the large legacy produced by the Turkoman contemporaries of the Eretnids, who ruled comparably smaller realms.[49] Köşkmedrese is a khanqah that was used as the burial place of the Eretnid sultans and consorts. According to the inscriptions on the building that ceased to exist, it was built by Eretna in memory of his consort Suli Pasha in 1339.[50] The name Kālūyān, possibly that of an Armenian architect, appears on the building.[51]

Literature

There is a scant number of literary works that were dedicated to the Eretnids. One such text was a short Persian tafsir in al-As'ila wa'l-Ajwiba by Aqsara'i commissioned by the Eretnid emir of Amasya, Sayf al-Din Shadgeldi (died 1381). Another instance was an astrological almanac (taqwīm) created for the last Eretnid ruler ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn Ali in 1371–2.[31]

_commissioned_for_Ghiyath_al-Din_Sultan_Muhammad_ibn_Sultan_Eretna%252C_signed_Mubarakshah_ibn_'Abdullah%252C_eastern_Anatolia%252C_dated_1353-54.jpg.webp)

Family tree

Eretna's parents were Jafar[3] or Taiju Bakhshi and his wife Tükälti.[4] His elder brothers were Emir Taramtaz and Suniktaz.[52] Eretna's wives included Suli Pasha (died 1339),[53] Togha Khatun[lower-alpha 1] and Isfahan Shah Khatun.[54] He was known to have had three sons: Hasan, Muhammad, and Jafar. The oldest son,[53] Sheikh Hasan was the governor of Sivas[27] and died in December 1347[27] or January 1348[55] due to sickness shortly after he wed an Artuqid princess.[55] Eretna's successor and youngest son, Ghiyath al-Dīn Muhammad I was born to Isfahan Shah Khatun, who was a relative of the Jalayirid ruler Hasan Buzurg.[53]

Muḥammad's son ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn ʿAlī succeeded him after his murder. According to Karamanname, Muḥammad also had an older son named Eretna. He was at some point declared as the ruler but was defeated and imprisoned by the Karamanids. While he held the throne for some time, he was eventually killed by ʿAlāʾ al-Dīn of Karaman. Muḥammad's son Eretna had two sons named Esenbogha and Ghazi, the first of which is reputed to have a tomb in Niğde. However, he is not mentioned by any sources of that era other than Karamanname.[56]

'Ali's only known son was Muhammad II Chelebi.[57] Khuvand Islamshah Khatun was either the mother or consort of 'Ali. She appears in records as a noble carrying weight in the Eretnid court, where she ordered a copy of Tavarikh-i Jahangusha-yi Ghazani. The possibility that she was 'Ali's consort is supported by a reference to him as the person of the highest authority, or Shahzada-yi Jahan, along with her, Khuvandegar Khatun, and the remark "may their dominion live on and their majesty be eternal." There, she was described as "the Bilqis of the age and time," "Banu of Iran-zamin of the time," and "pride of the illustrious family (urugh) of Chingiz Khan."[58]

Muḥammad is reputed to have had 2 sons, Yūsuf Chelebī (died 1434) and Aḥmad (d. 1433), and 3 daughters, Neslīkhān Khātūn (d. 1455), ʿAīsha (d. 1436), and Fātima (d. 1430). Aḥmad had a son named Muḥammad (d. 1443) and grandson Aḥmad, who was attested to be living in 1477.[59]

| The family tree of Eretnid dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

References

- 1 2 Spuler & Ettinghausen 2012.

- ↑ Bosworth 1996, p. 234; Masters & Ágoston 2010, p. 41; Nicolle 2008, p. 48; Cahen 2012; Sümer 1969, p. 22; Peacock 2019, p. 51.

- 1 2 3 Bosworth 1996, p. 234.

- 1 2 Sümer 1969, p. 22.

- ↑ Bosworth 1996, p. 234; Nicolle 2008, p. 48; Cahen 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cahen 2012.

- ↑ Nicolle 2008, p. 48.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, pp. 23, 93.

- 1 2 3 4 Peacock 2019, p. 50.

- 1 2 Melville 2009, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 Melville 2009, p. 92.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 93.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 92.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 101.

- ↑ Melville 2009, p. 94.

- ↑ Melville 2009, p. 94–95.

- ↑ Melville 2009, p. 95.

- ↑ Sinclair 2019, p. 89.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 104.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 105.

- ↑ Sinclair 1989, p. 286.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 104–105.

- 1 2 Sümer 1969, p. 110.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 164.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 111.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Göde 1995.

- ↑ Peacock 2019, p. 51.

- ↑ Peacock 2019, p. 182.

- ↑ Peacock 2019, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 Peacock 2019, p. 62.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 115.

- ↑ Melville 2009, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 177.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 177–178.

- ↑ Alıç 2020, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 178–179.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 179–180.

- ↑ Sinclair 2019, link.

- 1 2 Çayırdağ 2000, p. 450.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 181.

- 1 2 Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 182.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968.

- ↑ Çayırdağ 2000, p. 451.

- 1 2 Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 183.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 184.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 183–184.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 186–187.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 114.

- ↑ Durukan 2002.

- ↑ Jackson 2020, link.

- ↑ Sümer 1969, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 175.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 175; Göde 1995.

- 1 2 Sümer 1969, p. 121.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 180–181.

- ↑ Uzunçarşılı 1968, p. 184–186.

- ↑ Melville 2010, p. 137.

- ↑ von Zambaur 1927, p. 155.

Bibliography

- Alıç, Samet (2020). "Memlûkler Tarafından Katledilen Dulkadir Emirleri" [The Dulkadir's Emirs Killed by the Mamluks]. The Journal of Selcuk University Social Sciences Institute (in Turkish) (43): 83–94. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1996). New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press.

- Cahen, Claude (2012). "Eretna". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. II. E. J. Brill.

- Çayırdağ, Mehmet (August 2000). "Eretnalı Beyliğinin Paraları" [Coinage of the Eretna Principality]. Belleten (in Turkish). Turkish Historical Society. 64 (240): 435–452. doi:10.37879/belleten.2000.435. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- Durukan, Aynur (2002). "Köşkmedrese". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. TDV İslâm Araştırmaları Merkezi. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- Göde, Kemal (1995). "Eretnaoğulları". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi. TDV İslâm Araştırmaları Merkezi. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- Jackson, Cailah (4 September 2020). Islamic Manuscripts of Late Medieval Rum, 1270s-1370s Production, Patronage and the Arts of the Book. Edinburgh University Press.

- Masters, Bruce Alan; Ágoston, Gábor (2010). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase.

- Melville, Charles (12 March 2009). "Anatolia under the Mongols". In Fleet, Kate (ed.). The Cambridge History of Turkey (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 51–101. doi:10.1017/chol9780521620932.004. ISBN 978-1-139-05596-3. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- Melville, Charles (21 April 2010). Suleiman, Yasir; Al-Abdul Jader, Adel (eds.). "Genealogy and Exemplary Rulership in the Tarikh-i Chingiz Khan". Living Islamic History: Studies in Honour of Professor Carole Hillenbrand. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press: 129–150. doi:10.3366/edinburgh/9780748637386.003.0009. ISBN 9780748637386.

- Nicolle, David (2008). The Ottomans: Empire of Faith. Thalamus. ISBN 978-1-902886-11-4.

- Peacock, Andrew Charles Spencer (17 October 2019). Islam, Literature and Society in Mongol Anatolia. Cambridge University Press.

- Sinclair, T. A. (31 December 1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey. Vol. II. Pindar Press. ISBN 978-0-907132-33-2.

- Sinclair, Thomas (6 December 2019). Eastern Trade and the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages: Pegolotti's Ayas-Tabriz Itinerary and Its Commercial Context. Taylor & Francis.

- Spuler, Bertold; Ettinghausen, Richard (2012). "Īlk̲h̲āns". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. II. E. J. Brill.

- Sümer, Faruk (1969). "Anadolu'da Moğollar" [Mongols in Anatolia] (PDF). Journal of Seljuk Studies (in Turkish). Ankara: Selçuklu Tarih ve Medeniyeti Enstitüsü (published 1970). Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- Uzunçarşılı, İsmail Hakkı (20 April 1968). "Sivas - Kayseri ve Dolaylarında Eretna Devleti" [State of Eretna in Sivas - Kayseri and Around]. Belleten (in Turkish). Turkish Historical Association. 32 (126): 161–190. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- von Zambaur, Eduard Karl Max (1927). Manuel de généalogie et de chronologie pour l'histoire de l'Islam avec 20 tableaux généalogiques hors texte et 5 cartes [Handbook of genealogy and chronology for the history of Islam: with 20 additional genealogical tables and 5 maps] (in French). H. Lafaire. Retrieved 20 March 2023.