Between the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the foundations of contemporary society were laid, marked in the political field by the end of absolutism and the establishment of democratic governments—an impulse that began with the French Revolution—and, in the economic field, by the Industrial Revolution and the consolidation of capitalism, which would have a response in Marxism and the class struggle. In the field of art, an evolutionary dynamic of styles began to follow one another chronologically with increasing speed, culminating in the 20th century with an atomization of styles and currents that coexist and oppose, influence and confront each other. The century began with the survival of Neoclassicism, a movement succeeded by Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism, Modernism and Symbolism.[1]

France

In this century, the frequent use of etching continued, employed by painters such as Daubigny, Millet, Whistler, Manet, Degas, Pissarro, etc. However, the use of lithography, initiated in the previous century, predominated, with two trends: one that sought to compete with photography by emphasizing the accuracy and sensitivity of its compositions, led by Claude Ferdinand Gaillard; and another more artistic and relaxed tone, represented by Léopold Flameng. During this period, printmaking became highly industrialized and reached high production levels, with large print runs aimed at an increasingly larger public. At the end of the century, and especially linked to the post-impressionist generation, lithography had a privileged means of expression in the poster, to which great artists such as Jules Chéret, Alphonse Mucha, Pierre Bonnard and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec devoted themselves.[2]

During this period, new techniques emerged—or some of those introduced in the previous century were consolidated—such as woodcut, steel engraving or stereotype. On the other hand, the invention of photography revolutionized the graphic arts and influenced new techniques: in 1827, Nicéphore Niépce introduced heliography, made on a zinc plate sensitized to light and hollow engraved with acid; in 1852, Joseph Lemercier invented photolithography, a photonegative on glass projected on lithographic stone sensitized to light; in the same year, the cliché verre appeared, a glass cliché printed on photosensitive paper; and in the 1860s, photoengraving appeared, using a plate covered with a varnish or photosensitive resin attacked by acid, without the intervention of the artist. Another new technique, unrelated in this case to photography, was gillotage—also called zincography—invented by Firmin Gillot in 1850, which consisted of transferring a drawing to a zinc plate attacked with acid and stamped with a typographic press. The progressive industrialization of printmaking increasingly led to a differentiation between the artisan printmaker and the artist engraver—or painter-engraver—who demanded greater recognition for his creative work.[3]

Romanticism and realism

Romanticism was a style born at the beginning of the century, although it had already been forged at the end of the previous one in a so-called pre-romanticism. It was a movement of profound renewal in all artistic genres, which paid special attention to the field of spirituality, fantasy, feeling, love of nature, along with a darker element of irrationality, attraction to the occult, madness, dreams. Popular culture, the exotic, the return to underrated artistic forms of the past—especially medieval ones—were especially valued, and the landscape gained notoriety, which became a protagonist in its own right. The Romantics had the idea of an art that arose spontaneously from the individual, which is why they emphasized the figure of "genius": art is the expression of the artist's emotions.[4]

Romanticism was succeeded by realism, a trend that emphasized reality, the description of the surrounding world, especially of workers and peasants in the new framework of the industrial era, with a certain component of social denunciation, linked to political movements such as utopian socialism. These artists moved away from the usual historical, religious or mythological themes to deal with more mundane themes of modern life.[4]

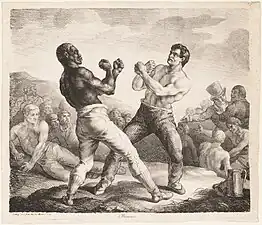

In France, the turn of the century saw the transition from Neoclassicism to Romanticism. Two of the best French Romantic painters, Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix, practiced lithography.[5] Géricault produced between 1817 and 1820 seven lithographic stones dedicated to the Napoleonic army, as well as other single works including Horses Fighting in a Stable and Boxing Match; during a stay in Great Britain between 1820 and 1821, he produced a number of prints of scenes from everyday life.[6] Delacroix made prints generally of literary inspiration, such as his series of seventeen lithographs of Goethe's Faust (1826), which was praised by the writer himself; or his series of Shakespeare's Hamlet (1843).[7]

Among the French printmakers of this period are: Louis Pierre Henriquel-Dupont was noted for his prints reproducing artists of the past and of his time;[8] Claude Ferdinand Gaillard was a skilled draughtsman and virtuoso engraver, author of reproductions such as Rembrandt's Supper at Emmaus, Botticelli's Madonna and Child, and Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa;[9] Léopold Flameng reproduced Van Eyck, Van der Goes, Rembrandt and Ingres, and published numerous plates in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts;[10] Jean Gigoux was an exponent of the troubadour style, illustrator of books such as Gil Blas and Abelard and Heloise;[11] Ernest Meissonier illustrated various books, including the works of Balzac; Charles Meryon was a talented engraver, author of etchings of views of Paris that are notable for their chromatic distribution and luminous intensity.[12] Also noteworthy was the rise of caricature, practiced by artists such as Henry Monnier, J. J. Grandville, Paul Gavarni and Charles Philipon, and published in magazines and newspapers such as Le Miroir, La Pandore, La Caricature and Le Charivari.[13]

In the times of realism, Honoré Daumier should be mentioned first. He worked for a while in a lithography workshop, until he was hired by Philipon for La Caricature thanks to his skills as a draughtsman. In 1831, his caricature of Louis Philippe I as Gargantua earned him six months in prison, but also brought him enormous fame. From then on he carried out an intense lithographic work (about four thousand works), especially in Le Charivari, either in series (Robert Macaire, 1836-1838; Babists, 1839; Gods of Olympus, 1841; People of Justice, 1845-1848; Tenants and Landlords, 1848) or single pieces, which he later grouped in albums such as Actualities or All That is Wanted. In general, his work was satirical, in which he mocked the bourgeoisie and the circles of power, with a style of curved lines and modulated figures with a sculptural appearance.[14]

Linked to realism was the Barbizon landscape school (Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Charles-François Daubigny, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña), marked by a pantheistic feeling for nature, with a concern for the effects of light in the landscape, such as the light that filters through the branches of the trees.[15] Almost all of its members practiced printmaking—especially etching—with the work of Corot, who began late in graphic art but mastered it with mastery. He produced about fifteen etchings and another fifteen lithographs, as well as about seventy cliché verres, generally landscapes.[16] Jean-François Millet, a notable painter especially dedicated to peasant themes, as in his famous The Angelus, was related to this school. In his graphic work he showed the influence of Rembrandt, especially in his luminous effects, with a concise and decisive stroke, as in The Wool Carder (1855).[17]

A special place should be given to Gustave Doré, one of the best engravers of his time. Gifted in drawing, at the age of twenty-two he illustrated Gargantua and Pantagruel by Rabelais (1854) and, the following year, Balzac's Amusing Tales (1855). Since then his production was intense, generally in woodcut, with an anachronistic style far from stylistic novelties, although his work shows the influence of Dürer, Rembrandt and the English romantics, especially Blake and Turner: Dante's Divine Comedy (1857-1867), Shakespeare's The Tempest (1860), Perrault's Tales (1862), Cervantes' Don Quixote (1863), Shakespeare's Macbeth (1863), Chateaubriand's Atala (1865), the Bible (1866), Milton's Paradise Lost (1866), La Fontaine's Fables (1867), Samuel Taylor Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1870), Alfred Tennyson's Idylls of the King (1875), Ariosto's Orlando Furioso (1877), Edgar Allan Poe's The Raven (1884).[18]

During this century, a type of woodcut ("à la langue de chat") was practiced in France, especially for book illustration. It was promoted mainly by the Englishman Charles Thompson, who founded a woodcut school in Paris in 1817. Practiced by artists such as Daumier, Doré and Meissonier, some of its best exponents were Célestin Nanteuil and Tony Johannot.[19] Lithography was also very popular: in 1816 Charles Philibert de Lasteyrie and Godefroy Engelmann opened their workshops in Paris, and in 1820 it was the technique chosen by Isidore Taylor to illustrate his Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l'ancienne France, in collaboration with a wide range of artists. It was used by artists such as Delacroix and Daumier, and caricaturists such as Grandville and Gavarni.[20]

In the years 1830-1840 the use of etching began to resurface among artists: in 1835 Rodolphe Bresdin made several etchings, in 1844 Théodore Chassériau produced fifteen etchings for an edition of Othello, and Camille Corot practiced this technique in the mid-1840s. Félix Bracquemond exhibited four etchings at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. In 1861 the Société des aquafortistes was founded in Paris, with the aim of bringing art for art's sake to printmaking. Its promoter was the entrepreneur Alfred Cadart, who had the collaboration of artists such as Charles-François Daubigny and Charles Jacque. Its members included Bracquemond, Corot, Daubigny, Millet, Meryon, Daumier and Delacroix, as well as Gustave Courbet, Henri Fantin-Latour, Carlos de Haes, Johan Barthold Jongkind, Maxime Lalanne, Alphonse Legros, Édouard Manet, Théodule Ribot, etc. His main organ was the publication Eaux-Fortes modernes. Publication artistique d'œuvres originales par la Société des aquafortistes, with a monthly circulation; between 1863 and 1867 five albums were published with compilations of the magazine, in the first of which, prefaced by Théophile Gautier, the term "aquafortist" emerged as a synonym for original engraver. One of its members, Lalanne, published in 1866 the Treatise on Etching, in which he described new ways of practicing this technique, such as "a la pluma", done with pen on copper; or retroussage, the cleaning with a muslin on the inked sheet, with which glazes, tones and half tints are obtained.[21]

Germany and Austria

In Germany and Austria, printmaking was practiced by painters such as: Adrian Ludwig Richter, who engraved views of Dresden and illustrated books such as Volksmärchen der Dentschen by Johann Karl August Musäus (1841);[22] Moritz von Schwind illustrated popular legends;[23] Adolph von Menzel inherited a lithographic company from his father, with which he achieved his first successes as an artist (Life of Frederick the Great, 1840-1842);[24] Wilhelm Leibl devoted himself mainly to genre genre.[23] Lithography was practiced by Karl von Piloty and Johann Nepomuk Strixner, authors of facsimiles of drawings and paintings from the Berlin and Munich galleries.[25] An offshoot of Romanticism was the German movement of the Nazarenes, inspired by the Italian Quattrocento and the German Renaissance, mainly Dürer. Prominent among their ranks was Johann Friedrich Overbeck, who was a notable engraver, author of thirty-six carvings of the Gospels.[23]

United Kingdom

During the first decades of the century, Romanticism, which had already had some notable antecedents in Füssli and Blake, predominated in Great Britain. One of its most outstanding exponents was Joseph Mallord William Turner, a landscape painter who stood out for the atmospheric and luminous effects of his works. In the graphic field he was the author of a series entitled Liber Studiorum (1807-1819), inspired by the Liber Veritatis by Claude Lorrain, a set of seventy-one mezzotintsin which he recreated various types of landscape: marine, mountainous, historical, architectural and epic.[26] Also worth mentioning are: Abraham Raimbach, illustrator of Gil Blas (1809) and Don Quixote (1818);[27] George Cruikshank, caricaturist and illustrator, author of works of satirical content (Life in London, 1821; Sketches by Boz, 1836; Oliver Twist by Dickens, 1838; Bottle, 1847);[28] and Francis Seymour Haden, a self-taught artist who did mostly landscapes, first president of the Royal Society of Painter-Printmakers, founded in London in 1880.[29]

The school of the Pre-Raphaelites emerged in this country, who were inspired—as their name suggests—by Italian painters before Raphael, as well as by the newly emerging photography, with exponents such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Edward Burne-Jones, John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Ford Madox Brown.[30] The members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood mainly practiced testa woodcut. Of particular note was the work of Rossetti, who illustrated Tennyson's poems (1857) and the Old Italian Poets (1861).[31]

Italy

In Italy, the work of Luigi Calamatta, a Paris-trained burilist, who basically devoted himself to reproducing works by Ingres, was noteworthy. Paolo Mercuri, director of the Vatican Chalcography, was a notable engraver, dedicated to reproducing the images of the Raphael's Rooms, in collaboration with other artists.[32]

Spain

In Spain, the first lithography workshop was opened in Madrid in 1819, directed by Felipe Cardano; two years later, another one was opened in Barcelona, directed by Antonio Brusi. In 1825 King Ferdinand VII promoted the creation of the Royal Lithographic Establishment, whose direction was entrusted to José de Madrazo, who was in charge of the edition of two hundred prints with reproductions of paintings of the Royal Sites and public buildings, made by artists such as Fernando Brambila, Florentino Decraene, José Camarón Boronat, Gaetano Palmaroli and Gaspar Sensi.

In 1835, the romantic magazine El Artista began to be published, which included illustrations of stories and poetry, as well as portraits and other images by artists such as Federico de Madrazo, Hélène Feillet and Carlos Luis de Ribera. In 1839, Francisco Javier Parcerisa began the series Recuerdos y bellezas de España (1839 -1865), a total of ten volumes with images of monuments and landscapes of Spain. Similarly, between 1842 and 1850, Jenaro Pérez Villaamil published his series España artística y monumental, with 144 prints of the most outstanding monuments of Spain. Another notable series was Pedro de Madrazo's El Real Museo de Madrid y las joyas de la Pintura de España (The Royal Museum of Madrid and the Jewels of Spanish Painting) (1857).[33]

There were also Domingo Martínez Aparici, professor of engraving at the San Fernando Academy, reproducer of works by the great Renaissance and Baroque masters; Bernardo Rico, illustrator of books and newspapers; Arturo Carretero, notable woodcutter, contributor to several newspapers; Joaquín Pi y Margall, dedicated to sweet carving with reproductions of John Flaxman and Joseph von Führich and contributor to the series Monumentos Arquitectónicos de España (1859 -1881); Bartolomé Maura, author of etchings of portraits and reproductions of Spanish paintings; Leonardo Alenza followed in the line initiated by Goya, with romantic and temperamental images, mainly portraits and genre scenes; Eugenio Lucas was equally influenced by Goya, author of etchings on trivial subjects and divertimentos; Mariano Fortuny was an outstanding painter and draughtsman, author of some forty etchings with subjects inspired by his stay in Morocco, such as El árabe muerto and La familia marroquí (The Dead Arab and The Moroccan Family); Carlos de Haes was a notable landscape painter, author of fifty-four prints grouped in Ensayos de grabado al aguafuerte; José María Galván was dedicated to reproduction etching—especially Goya—and collaborated with the publication El Artista al aguafuerte.[34]

Boxing Match (1818), by Théodore Géricault, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Boxing Match (1818), by Théodore Géricault, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Royal Pond of the Courtyard of the Alhambra in Granada (1824), by Felipe Cardano, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid.

Royal Pond of the Courtyard of the Alhambra in Granada (1824), by Felipe Cardano, Biblioteca Nacional de España, Madrid. Cascada de la Granja, from the Vistas de los Sitios Reales y Madrid (1830), by Fernando Brambila.

Cascada de la Granja, from the Vistas de los Sitios Reales y Madrid (1830), by Fernando Brambila. Sepulcro en el monasterio del Parral de Segovia, from the series España artística y monumental (1842), by Jenaro Pérez Villaamil.

Sepulcro en el monasterio del Parral de Segovia, from the series España artística y monumental (1842), by Jenaro Pérez Villaamil.

A Young Mother at the Entrance to a Wood (1856), cliché-verre by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

A Young Mother at the Entrance to a Wood (1856), cliché-verre by Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Mona Lisa (1858), by Luigi Calamatta.

Mona Lisa (1858), by Luigi Calamatta.

Impressionism

Impressionism was a profoundly innovative movement, which meant a break with academic art and a transformation of the artistic language, thus initiating the path towards the avant-garde movements. The Impressionists were inspired by nature, from which they sought to capture a visual "impression", the capture of an instant on canvas—influenced by photography—with a technique of loose brushstrokes and clear and luminous tones that especially valued light. A new subject matter emerged, derived from the new way of observing the world: together with landscapes and seascapes, urban and nocturne views, interiors with artificial light, scenes of cabaret, circus and music hall, characters of the bohemia, beggars, outcasts, etc.[35]

Of great importance during this period was the influence on the graphic arts of Japanese printmaking, which spread profusely through the West. The Japanese woodcut influenced above all the use of flat colors, new concepts in the use of perspective, elegance of line and boldness in the assembly of form and color. The taste for Japanese prints was introduced mainly by Félix Bracquemond and was especially prevalent in the 1880s and 1890s. Its influence is most evident in the work of Mary Cassatt and Henri Rivière, as well as in the group of the Nabis—especially Pierre Bonnard—and other artists such as Whistler, Manet and Fantin-Latour. Also noteworthy is the popularizing work of the magazine Le Japon Artistique, published by Samuel Bing between 1888 and 1891.[36]

_1895.jpg.webp)

It is also worth mentioning the importance of newspaper and magazine illustration during this period, in which both painters and graphic artists took part. Some painters marginalized by academic circles and official salons found a way to publish their works, such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri-Gabriel Ibels, Adolphe Willette, Théophile Alexandre Steinlen, Louis Anquetin, Hermann-Paul and Jean-Louis Forain. Among these illustrated newspapers it is worth remembering: Les Temps nouveaux, Le Courrier français, La Revue Blanche, L'Escarmouche and Le Chambard.[37]

In the 1880s, after the experience of the Société des aquafortistes, there was an initiative to revalue the original print not only in etching, but in all printmaking techniques. To this end, the Société de l'estampe originale was created, as well as the publication L'Estampe originale, directed by Auguste-Louis Lepère, which published two albums in 1888 and 1889 that despite their limited success laid the foundations for a greater awareness of the artistic work of the engraver. Members of this society were Félix Bracquemond, Whistler, James Tissot, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Tony Beltrand and Daniel Vierge. The commercial failure of this initiative came from the higher price derived from the original work, so the idea began to take shape that the public should be made aware of the exclusivity of this type of creations, the product of the artist's genius, through a handcrafted and not merely industrial process. Despite the contradiction that one of the hallmarks of printmaking is its repetition, the aim was to single out the original print. Thus arose the technique of eau-forte mobile ("variable etching"), initiated by Ludovic-Napoléon Lepic, consisting of inking the plate differently in each printing, so that an infinite number of variables can arise from the same composition and each print becomes unique. These unique prints were called belle épreuve ("rare proof") and became part of the catalogs of art galleries, usually in limited and numbered editions, intended for collectors. Although they started with etching, they later moved on to lithography as well. This new concept was taken up by the Société des Peintres-Graveurs, founded in 1889 and directed by Félix Bracquemond, which brought together painters who were also interested in printmaking as an aspect of their artistic activity, among them Edgar Degas, Auguste Rodin, Odilon Redon, James Tissot, Camille Pissarro, Mary Cassatt, Eugène Carrière, Marc Chagall, Édouard Vuillard, Henri Fantin-Latour and Albert Besnard.[38]

One of the artists who most practiced printmaking was Édouard Manet—generally considered a pre-impressionist—author of about one hundred works, most of which were not published. An admirer of Goya and Rembrandt, in his prints he did not faithfully reproduce paintings or drawings, but interpreted them in black and white, seeking his own form of expression. He practiced etching and lithography, always in a personal and novel way. His most creative periods in printmaking were 1860-1863 and 1865-1874; in the former he made about forty etchings, while in the latter he focused more on illustrations for books, generally in lithography and gillotage. One of his most famous works is El globo, a lithograph of 1862, resolved in a free and heterodox way, so it was not published at the time. His Execution of Maximiliano (1868) was censored by the authorities. In 1874 he made Polichinela, a caricature of president Mac-Mahon, which was also banned. In 1875 he illustrated The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe and, the following year, The Afternoon of a Faun by Stéphane Mallarmé.[39]

Among the impressionists, the graphic work of Edgar Degas, who was aware of the power of printmaking as a means of disseminating his works, is worth mentioning. He began etching at the age of twenty-two, although later he would also practice aquatint, lithography and monotype. His early works show the influence of Rembrandt, although his style evolved thanks to the influence of artists of his time such as Manet, Whistler, Tissot and Bracquemond. In his work we can perceive the desire for experimentation and innovation, as well as the insistence on working alone. In an early period (1856-1864) he devoted himself mainly to portraiture, influenced by Rembrandt, Delacroix and Ingres. After a few years of inactivity, in 1875 he resumed his graphic work and began to depict his favorite subjects: dancers, theater and music hall scenes, cafés, brothels and toilette scenes. Under the influence of his friend Marcellin Desboutin, he then practiced the drypoint style esquisses sur métal, which combined printmaking and drawing. Soon after, he became interested in original printmaking and monotype, a technique in which he experimented with various methods, in combination with oil or pastel. In these works he especially expressed his interest in the effects of artificial light, which sometimes took on an almost abstract appearance. Between 1879 and 1880, he experimented with new printmaking tools, such as the emery pencil and the carbonic arc or electric pencil, with which he created new tonal effects. He also worked in lithography, generally with autographic paper, sometimes transferring monotypes. He also used photography to obtain motifs, using the positives as the basis for his graphic compositions. From 1884, he practically abandoned his graphic work, which he partially resumed at the end of the 1880s with a lithographic series dedicated to the female nude. Already in the 1890s he definitively abandoned printmaking in favor of photography.[40]

Other Impressionist artists who practiced printmaking were: Camille Pissarro, who practiced etching in an original way, seeking different variations of the same image, for which he started from a simple drypoint or etching sketch and applied successive aquatints in different states and colors;[41] Pierre-Auguste Renoir devoted himself above all to lithography, generally with the reproduction of his pictorial work, with images that have the appearance of pastel, with rounded volumes and voluptuous atmospheres;[42] Mary Cassatt was one of the artists who most assumed the Japanese influence—especially of Utamaro—from which she adopted both the forms, compositions and perspectives and the color schemes, all of which she applied to some images of Western context, generally domestic and family images, with a preference for the relationship between mothers and children.[43]

Also noteworthy is the work of the American artist based in the United Kingdom James McNeill Whistler, a painter of intense lyricism who seeks in his images to capture the atmosphere and atmospheric effects, daytime and nighttime luminosity. He practiced etching, lithography, and drypoint. He was one of the first artists to engrave directly on copper, painting rather than inking the metal, to capture the instant in a more suitable way, so that all his prints were unique.[41] In 1858 he published a series of twelve sketched prints of the Parisian districts of Montrouge and Montmartre, and the following year a similar one of views of the Thames; he had to wait twenty years for his third series, this time on Venice.[44]

In Germany, the main Impressionist artists were Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth and Max Slevogt. The first evolved from realism to impressionism, author of landscapes, portraits and peasant scenes;[45] Corinth also straddled realism, impressionism and, at the end of his career, expressionism, with a profuse graphic oeuvre of nine hundred works between lithographs and drypoints, with quick and sharp strokes, some of them in series (Luther, Anne Boleyn, Götz von Berlichingen);[46] Slevogt produced series of lithographed and etched illustrations on copper, with confident drawing and creative fantasy (Lederstrumpf by James Fenimore Cooper, 1906-1909).[47]

The Swedish Anders Zorn practiced etching, with a sober and spontaneous style, more concerned with expression than with technical quality, author of portraits, nudes and genre scenes.[48]

In Spain, the work of Tomás Campuzano, painter of landscapes and seascapes in the pleinairistic style; Ricardo de los Ríos, a reproductive watercolorist and author of landscapes and portraits, such as Garibaldi and Carlos de Haes; and Juan Espina, a landscape painter with a plenairistic tone.[49]

After the first impressionist generation, several artists emerged in France who, while starting from its premises, evolved towards new forms of expression, which are usually grouped into two currents: Neo-Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The first was characterized by the technique of pointillism (or divisionism), consisting of composing the work through a series of dots of pure colors, which are placed next to others of complementary colors, merging in the retina of the viewer in a new tone.[50] Its main exponent in the graphic field was Paul Signac, author of lithographs in which he reflected his pictorial compositions, centered on landscapes, portraits and social scenes.[51]

For their part, the Post-Impressionists reinterpreted in a personal way the new technical discoveries made by Impressionism, thus opening different paths of development of great importance for the evolution of art in the twentieth century. Thus, rather than a particular style, post-impressionism was a way of grouping diverse artists of different sign, among whom Vincent van Gogh, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Paul Cézanne stand out.[52] Van Gogh was the author of works of strong dramatism and interior prospection, with sinuous and dense brushstrokes, of intense color, in which he deforms reality, to which he gave a dreamlike air.[53] He did not work much in the graphic field, of which only nine lithographs are known from his Dutch period (1882-1885), usually reproductions of his works, such as The Potato Eaters (1883-1885); and an etching made in Auvers-sur-Oise, the Portrait of Doctor Gachet (1890).[54][55]

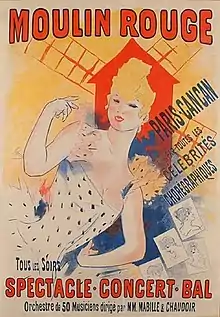

Toulouse-Lautrec's work was strongly marked by graphic art. In 1886 he began to collaborate with the publication Le Courrier français, for which he made drawings that were transferred to photorealism. He worked mainly in color lithography, in which he created prints and posters inspired by the night life of Paris (cafés, theaters, cabarets), with a realistic style but with a decorative tone that combined naivety and social satire. In his images appear scenes of chandeliers with singers and dancers in dramatic and disproportionate gestures, seen from the perspective of a person suffering from dwarfism. In 1893 he made with Henri-Gabriel Ibels the series of twenty-two lithographs Le Café-Concert, in which they portrayed the most famous variety actors of the time. He also dealt with the subject of prostitution, in his series of eleven lithographs Elles (1896), in which he portrays moments of intimacy of these women, which might seem like domestic interiors if it were not for a subtle eroticism that he confers to the scenes.[56]

Cézanne is often considered a pioneer of the artistic avant-garde of the 20th century. In his works he structured the composition in geometric forms (cylinder, cone and sphere), in an analytical synthesis of reality precursor of cubism. He practiced lithography, in reproductions of his works, generally landscapes, portraits and nudes—especially of bathers.[57]

L'Attente (1877), by Ricardo de los Ríos

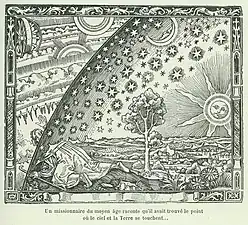

L'Attente (1877), by Ricardo de los Ríos Flammarion engraving (1888), anonymous

Flammarion engraving (1888), anonymous The Bath (1890-1891), by Mary Cassatt, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.

The Bath (1890-1891), by Mary Cassatt, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C. En la costa gallega, esperando la sardina (1894), by Tomás Campuzano

En la costa gallega, esperando la sardina (1894), by Tomás Campuzano

_1895.jpg.webp) Souvenir (the guitar) (1895), by Anders Zorn

Souvenir (the guitar) (1895), by Anders Zorn_(The_Large_Bathers)_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) The Bathers (1896-1897), by Paul Cézanne, Blanton Museum of Art, Austin

The Bathers (1896-1897), by Paul Cézanne, Blanton Museum of Art, Austin

Modernism and Symbolism

The two main movements of the transition between the 19th and 20th centuries were modernism and symbolism. Modernism was an architectural movement that emerged around 1880 in several countries, according to which it received different names: Art Nouveau in France, Modern Style in the United Kingdom, Jugendstil in Germany, Sezession in Austria, Liberty in Italy and modernism in Spain, a country in which Catalan modernism stood out. It lasted until the beginning of the First World War.[58] This style, due to its ornamental character, meant a great revitalization of the graphic and decorative arts, with a new conception more focused on the creative act and on equating it with the rest of the plastic arts, to the point that its creators proposed for the first time the "unity of the arts". Modernist design generally proposed the revaluation of the intrinsic properties of each material, with organicist forms inspired by nature.[59]

Symbolism was a fantastic and dreamlike style that emerged as a reaction to the naturalism of the realist and impressionist currents, against whose objectivity and detailed description of reality they opposed subjectivity and the expression of the occult and the irrational; against representation, evocation or suggestion. A main characteristic of symbolism was aestheticism, a reaction to the prevailing utilitarianism of the time and to the ugliness and materialism of the industrial era. In contrast, symbolism gave art and beauty an autonomy of their own, synthesized in Théophile Gautier's formula "art for art's sake" (L'art pour l'art).[60]

France

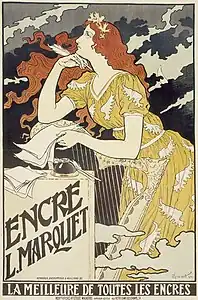

The last quarter of the century saw a great boom in poster design, especially in lithography. The great innovator of this medium was Jules Chéret, who turned advertising posters into true works of art. In 1866 he opened a lithographic workshop in Paris, from which he began a great work in posters that stood out for their colorfulness, with a careful composition and richness of effects. His main clients were Parisian theaters, such as the Folies Bergère, as well as businessmen and merchants. He followed in their footsteps Eugène Grasset, who associated the poster stylistically with Art Nouveau, inspired especially by nature, floral motifs and ornamental elements. Until almost 1890 few renowned artists practiced poster art—we should mention Édouard Manet (Champfleury-Les chats, 1868) and Honoré Daumier (Entrepôt d'Ivry, 1872)—but since then it became another means of expression for any artist. The most prominent name was that of Alfons Mucha, a Czech painter who settled in Paris, where he developed a great graphic work: [[his first great success was the poster for the play Gismonda by Sarah Bernhardt (1894), which pleased the actress so much that she hired him to make all her posters (Lady of the Camellias, 1896; Lorenzaccio, 1896; The Samaritan Woman, 1897; Medea, 1898; Hamlet, 1899; Tosca, 1899). Mucha's work focused on the female figure, a languid, melancholy figure with long hair and flowing gowns, adorned with jewels and framed in vegetal decoration.[61]

Between 1893 and 1895, L'estampe originale was published again, under the direction of André Marty. They released nine albums, where the work of seventy-four artists was exhibited, with the collaboration of the art critic Roger Marx. Inspired by the English Arts & Crafts movement, these artists sought the integration of the arts and of these with industry, as well as a revaluation of the decorative arts. Published quarterly, it had a print run of one hundred copies; the annual subscription cost 150 francs. The publication focused on the originality of the works, regardless of the technique used. It also encouraged experimentation and the use of new techniques (such as gypsographie, invented by Pierre Roche; or embossing, developed by Alexandre Charpentier), and strongly promoted color printing. Among the artists who participated in this initiative were: Odilon Redon, Eugène Carrière, Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, Henri-Gabriel Ibels, Maurice Denis, Félix Bracquemond, Jules Chéret, Henri Fantin-Latour, James McNeill Whistler, Camille Pissarro, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Auguste Rodin, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Signac, Théo van Rysselberghe, Paul Sérusier, Félix Vallotton, Constantin Meunier, Lucien Pissarro, Victor Prouvé, Walter Crane, Charles Ricketts, Antonio de la Gándara, Adolphe Willette, Auguste-Louis Lepère, Hermann-Paul and Jean-François Raffaëlli.[62]

The impulse to the graphic arts favored by modernism led to a boom in the publication of magazines. One of the pioneers was the British The Studio, which presented about a thousand annual reproductions of artistic works of all kinds. In the same country, The Yellow Book, directed by the illustrator Aubrey Vincent Beardsley, stood out. In Belgium, L'Art moderne and Van nu en Straks were published, where the main modernist novelties were presented and the work of Victor Horta and Henry Van de Velde was disseminated. In Germany, the literary and artistic magazines Pan, Jugend and Simplicissimus emerged, which stood out for their critical and satirical language. In Austria, Ver Sacrum was the main organ of the Viennese Secession, where artists such as Gustav Klimt and Koloman Moser collaborated. In Spain, the Barcelona-based Joventut published the early work of Picasso, as well as that of the leading artists of the time.[63]

Linked to symbolism is the Pont-Aven School, whose artists had a special predilection for lithography. In that town Breton met between 1888 and 1894 a series of artists led by Paul Gauguin, who developed a style heir to post-impressionism with a tendency to primitivism and a taste for the exotic, with varied influences ranging from medieval art to Japanese art. They developed a style called synthetism, characterized by the search for formal simplification and recourse to memory as opposed to painting copied from nature.[64] Gauguin and Émile Bernard produced several zincographs during this period, which were exhibited at the exhibition Peintures du Groupe Impressionniste et Synthétiste organized at the Café Volpini in Paris in 1889. Gauguin presented eleven zincographs (Dessins lithographiques) and Bernard six (Les bretonneries), showing landscapes and people of Brittany in a synthesist style. Other members of the group who practiced printmaking were Armand Seguin, Maxime Maufra and Roderic O'Conor. Later, during his stay in Tahiti, Gauguin practiced woodcut, to which he transferred his pictorial compositions of the time.[65]

Gauguin and the Pont-Aven group influenced the Nabis, a group of artists active in Paris in the 1890s, noted for an intense chromaticism of strong expressiveness.[66] Some of its members practiced printmaking, such as Maurice Denis, Paul Sérusier, Édouard Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard and Félix Vallotton. Denis was a painter, illustrator, lithographer and set designer, as well as an art critic. Influenced by Ingres and Puvis de Chavannes, as well as Gauguin and the Pont-Aven group, and with certain reminiscences to William Blake and Pre-Raphaelite painting, he developed a work of marked sentimentalism that denotes a naturalistic and pious conception of life. He illustrated books such as Édouard Dujardin's Reply of the Shepherdess to the Shepherd, Paul Verlaine's Sanity, Thomas de Kempis's Imitation of Christ or André Gide's Journey of Urien.[67] Bonnard was a painter, illustrator and lithographer. He was an excellent draughtsman, with softly contoured figures delicately expressing the subtlest movements.[68] Together with Vuillard, he developed a subject matter centered on a type of social atmosphere images reflecting everyday life in generally interior scenes, a style defined by critics as "intimism".[69] Vuillard was also a painter and lithographer and, like his friend Bonnard, his work focused on intimacy. Fond of photography, he sometimes used it as a starting point for his compositions.[70] The Swiss Vallotton began in woodcut, with a certain modernist tendency. His work is characterized by eroticism and black humor, with flatly composed nudes in which the influence of Japanese art is denoted and faces that look like masks.[71]

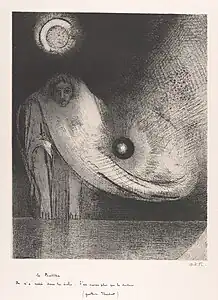

In France, one of the main symbolist artists was Odilon Redon, who developed a fantastic and dreamlike theme, influenced by the literature of Edgar Allan Poe, which largely preceded surrealism. Until the age of fifty, he worked almost exclusively in charcoal drawing and lithography, although he later showed himself to be an excellent colorist both in oil and pastel, with a style based on soft drawing and phosphorescent-looking coloring.[72] He illustrated numerous works by symbolist writers, such as Edgar Allan Poe or The Temptation of Saint Anthony by Gustave Flaubert (1886).[73]

Belgium

A notable Symbolist school developed in Belgium, most notably Félicien Rops and James Ensor. Rops was a painter and graphic artist of great imagination, with a predilection for subject matter centered on the fantastic and supernatural, perversity and eroticism.[74] He illustrated books by Baudelaire, Mallarmé and Barbey d'Aurevilly.[75] He chaired the International Society of Watercolorists founded in 1875.[76] Ensor had a preference for popular themes, translating them into enigmatic and irreverent scenes, absurd and burlesque in character, with an acid and corrosive sense of humor, centered on figures of vagabonds, drunks, skeletons, masks and carnival scenes.[77] He practiced etching, with a certain influence of Rembrandt, especially in chiaroscuro, with a quick, cursive stroke (Cathedral, 1886; Streetlight, 1888; Baths of Ostend, 1899).[78]

Germany

In Germany, the work of Max Klinger stands out. In his work the influence of Goya and Rembrandt can be appreciated, and the attraction for the fantastic and disturbing is perceived.[79] Of great technical and stylistic complexity, his work is plagued with fantasy and symbolic allusions. As a graphic artist he was a great innovator, especially in etching, in a style that predates surrealism, as denoted in his series A Glove (1881), centered on fetishism.[80] Klinger's main innovation was the introduction of narrative series—which he called opus—in which he narrated a story through successive prints; examples would be: Eve and the Future (1880), Cupid and Psyche (1880), Intermediates (1881), Dramas (1883), A Life (1884), A Love (1887), Death (1889 and 1898-1909) and Brahms Fantasy (1894). In his works he combined etching, aquatint, drypoint, burin and lithography. From Goya he took the modeling in function of light, a light of dramatic effects that articulates the scenes. He also introduced a new way of organizing space by emphasizing specific motifs in the image, as well as framing the images with a series of intertwined lines in the manner of an arabesque. His subject matter focuses on vital themes such as love and death, with a large dose of fantasy. He was also the author of a treatise on graphic art, Malerei und Zeichnung (1891). Here he defends, for example, the suitability of printmaking as the best means of expression of fantasy and imagination, of the world of the subconscious.[81]

Franz von Stuck was a painter, engraver, sculptor and architect, one of the founders of the Munich Secession.[71] He developed a decorative style close to modernism, although due to its subject matter it is more symbolist, with an eroticism of torrid sensuality that reflects a concept of woman as a personification of perversity.[82]

Munch

_(8477718108).jpg.webp)

The Norwegian Edvard Munch was also a great graphic artist. He created in his work a personal universe that reflects his existential anxieties, in which the influence of nietzschean philosophy is denoted. His work revolves around his personal obsessions regarding love and sex, as well as his conception of society as a hostile and oppressive environment.[83] In his graphic work he was directly influenced by Klinger, especially in his anguished and obsessive themes, in his existential concerns. He was initiated in etching in 1892, during a stay in Berlin, the result of which was the so-called Meier-Graefe Folder, published in 1894. Between 1895 and 1897 he lived in Paris, where he became acquainted with the latest technical innovations and was influenced by Manet, Toulouse-Lautrec, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Whistler, as well as the symbolists Rops and Redon. He worked then, in addition to etching, aquatint, drypoint, lithography and autograph, and experimented with the black way on zinc plates and wood carving. In 1895 a lithographic reproduction of his famous work The Scream was reproduced in La Revue Blanche. During his Parisian stay he tackled the cabaret theme, common in the post-impressionist environment, in the style of Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec; and he made some programs for the Théâtre de l'Œuvre ('Peer Gynt, 1896; John Gabriel Borkman, 1897). After his return to Norway he lived a few years of economic hardship, mitigated thanks to the sale of his graphic production. He never numbered his editions, reserving the right to make more printings according to demand. In general, in printmaking he followed the same compositional schemes as in his paintings, characterized by a strong contrast between foreground and background, sometimes using foreshortening. His works include: Madonna (1894-1895), Can-can (1895), Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm (1895), Melancholy I (1896), Anguish (1896), Moonlight (1896), The Sick Girl (1896) and The Kiss (1897). Munch's work was linked to the expressionism of the early 20th century, of which he was considered one of its main masters.[84]

United Kingdom

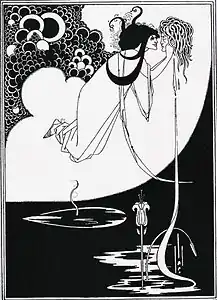

In the United Kingdom, it is worth mentioning Aubrey Vincent Beardsley, who was mainly a draughtsman, characterized by a sinuous line style very close to modernism, although it is considered symbolist by the choice of his subjects, often with strong erotic content. His drawing was influenced by Greek vase painting, with a decorative and somewhat perverse style, rhythmic and elegant, frivolous and tending to the grotesque.[85] His favorite subjects were also some of the most recurrent of symbolism: the femme fatale, the Arthurian cycle and the artistic universe wagnerian. In 1891 he illustrated the book Salome by Oscar Wilde.[86] Walter Crane was a painter, illustrator, typographer and designer of ceramics, stained glass, textiles, jewelry and posters. He began artistically in the Pre-Raphaelite style, influenced by the Romantic William Blake, whose style based on vibrant lines and arabesques powerfully influenced English modernism and symbolism. Also decisive in his work were the Florentine Quattrocento and Japanese woodcut. He focused on literary and mythological themes, with a language of fabulous and dreamlike symbols.[87]

Spain

In Spain, it is worth mentioning the work of: Rogelio de Egusquiza, author of etchings on Wagnerian themes; Alexandre de Riquer devoted himself mainly to book illustration and ex-libris design;[88] Mariano Fortuny y Madrazo also made Wagnerian scenes, as well as images of Venice, but not of its monumental sights, but of its small corners and everyday scenes.[89] It is also worth mentioning Catalan modernism, developed by artists such as Santiago Rusiñol and Ramón Casas, who developed a style mixing naturalism and symbolism, and who were authors of prints and posters of great quality. Hermenegildo Anglada Camarasa settled in France, where he made some prints—generally portraits—with dynamic lines. Joaquim Sunyer developed a style of expressive contours and evocative atmospheres, which he emphasized with color prints (En el Moulin Rouge, 1899).[90]

Pornokratès (1878), by Félicien Rops, Mabille collection, Rhode-Saint-Genèse

Pornokratès (1878), by Félicien Rops, Mabille collection, Rhode-Saint-Genèse Encre L. Marquet (1892), by Eugène Grasset, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

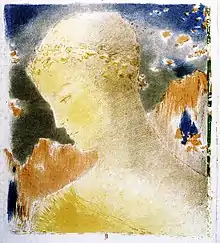

Encre L. Marquet (1892), by Eugène Grasset, Los Angeles County Museum of Art_(Tenderness_-_Tendresse)_MET_DP834406.jpg.webp) Madeleine (Deux têtes) (Tendresse) (1893), by Maurice Denis, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

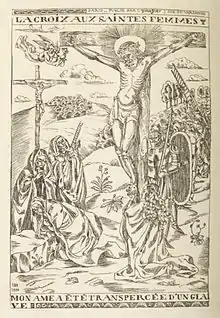

Madeleine (Deux têtes) (Tendresse) (1893), by Maurice Denis, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York La crois aux saintes femmes (1894), by Émile Bernard Musée des Beaux-Arts de Pont-Aven

La crois aux saintes femmes (1894), by Émile Bernard Musée des Beaux-Arts de Pont-Aven

Buda (1895), by Odilon Redon, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Buda (1895), by Odilon Redon, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Rue vue d'en haut, from the series Quelques aspects de la vie de Paris (1899), by Pierre Bonnard

Rue vue d'en haut, from the series Quelques aspects de la vie de Paris (1899), by Pierre Bonnard La Reine Parysatis ecorchant un eunuque (1900), by James Ensor

La Reine Parysatis ecorchant un eunuque (1900), by James Ensor.jpg.webp)

Notes

- ↑ Azcárate Ristori, Pérez Sánchez & Ramírez Domínguez (1983, p. 702)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 594)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 6–8)

- 1 2 Laneyrie-Dagen (2019, pp. 227–232)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, p. 788)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 793)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 494)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 909)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 231–232)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 233)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 801)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1325)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 235)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 483)

- ↑ Azcárate Ristori, Pérez Sánchez & Ramírez Domínguez (1983, p. 731)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 408)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 136)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 524)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 2110)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1175)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 12–13)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1708)

- 1 2 3 Esteve Botey (1935, p. 121)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1321)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 122–123)

- ↑ "J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours".

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 260)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 436)

- ↑ Holroyd, Charles (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). pp. 797–798.

- ↑ Azcárate Ristori, Pérez Sánchez & Ramírez Domínguez (1983, pp. 736–738)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 264–266)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 152–153)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 323–326)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 327–331)

- ↑ Laneyrie-Dagen (2019, pp. 237–242)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 22–25)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 50–53)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 28–33)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 14–17)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 34–48)

- 1 2 Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 138)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 140)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 139–140)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 262)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1161)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 404)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1868)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 271)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 332–336)

- ↑ Laneyrie-Dagen (2019, pp. 243–244)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1852)

- ↑ Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (1991, p. 774)

- ↑ Dempsey (2002, pp. 45–47)

- ↑ Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (1991, p. 2026)

- ↑ "Graphic Works".

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 70–72)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, pp. 357–358)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, p. 61)

- ↑ Borrás Gualis, Esteban Lorente & Álvaro Zamora (2010, p. 488)

- ↑ Laneyrie-Dagen (2019, pp. 248–250)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 18–22)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 66–70)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 102)

- ↑ Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (1991, p. 768)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 56–64)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, p. 669)

- ↑ Hofstätter (1981, pp. 93–95)

- ↑ Hofstätter (1981, p. 98)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, p. 128)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, p. 1002)

- 1 2 Gibson (2006, p. 243)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, pp. 789–790)

- ↑ Dempsey (2002, p. 43)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, p. 826)

- ↑ Gibson (2006, p. 241)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 196)

- ↑ Fernández Polanco (1989, pp. 50–52)

- ↑ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 568)

- ↑ Gibson (2006, pp. 234–235)

- ↑ Chilvers (2007, p. 517)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 74–77)

- ↑ Fernández Polanco (1989, p. 57)

- ↑ Fernández Polanco (1989, p. 56)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 78)

- ↑ Gibson (2006, pp. 78–80)

- ↑ Lucie-Smith (1991, p. 134)

- ↑ Fahr-Becker (2008, pp. 43–46)

- ↑ Esteve Botey (1935, pp. 332–337)

- ↑ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 158)

- ↑ "Grabados".

References

- Azcárate Ristori, José María de; Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso Emilio; Ramírez Domínguez, Juan Antonio (1983). Historia del Arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Anaya. ISBN 84-207-1408-9.

- Becks-Malorny, Ulrike (2007). Kandinsky. Köln: Taschen. ISBN -978-3-8228-3539-5.

- Borrás Gualis, Gonzalo M.; Esteban Lorente, Juan Francisco; Álvaro Zamora, Isabel (2010). Introducción general al arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Akal. ISBN 978-84-7090-107-2.

- Historia del grabado, ESTEVE BOTEY, Francisco, Barcelona, Labor, 1935

- Bozal, Valeriano (1989). El siglo de los caricaturistas (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- Carrete, Juan; Checa, Fernando; Bozal, Valeriano (2001). Summa Artis XXXI. El grabado en España (siglos XV-XVIII) (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpe. ISBN 84-239-5273-8.

- Carrete, Juan; Vega, Jesusa (1993). Grabado y creación gráfica (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- Cassou, Jean (1976). Picasso (in Spanish). Barcelona: Círculo de Lectores. ISBN 84-226-0868-5.

- Chilvers, Ian (2007). Diccionario de arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. ISBN 978-84-206-6170-4.

- Cirlot, Lourdes (1990). Las últimas tendencias pictóricas (in Spanish). Barcelona: Vicens-Vives. ISBN 84-316-2726-3.

- de la Plaza Escudero, Lorenzo; Morales Gómez, Adoración (2015). Diccionario visual de términos de arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Cátedra. ISBN 978-84-376-3441-8.

- Dempsey, Amy (2002). Estilos, escuelas y movimientos (in Spanish). Barcelona: Blume. ISBN 84-89396-86-8.

- Diccionario enciclopédico Larousse (in Spanish). Barcelona: Planeta. 1990. ISBN 84-320-6070-4.

- Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (in Spanish). Barcelona: Planeta-Agostini. 1988. ISBN 84-395-0976-6.

- Dube, Wolf-Dieter (1997). Los Expresionistas (in Spanish). Barcelona: Destino. ISBN 84-233-2909-7.

- Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (in Spanish). Madrid: Ediciones B. 1991. ISBN 84-406-2261-9.

- Esteve Botey, Francisco (1935). Historia del grabado (in Spanish). Barcelona: Labor.

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2008). El modernismo. Potsdam: Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8331-6377-7.

- Fatás, Guillermo; Borrás, Gonzalo M. (1990). Diccionario de términos de arte y elementos de arqueología, heráldica y numismática (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza. ISBN 84-206-0292-2.

- Fernández Polanco, Aurora (1989). Fin de siglo: Simbolismo y Art Nouveau (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- Gallego, Antonio (1999). Historia del grabado en España (in Spanish). Madrid: Cátedra. ISBN 84-376-0209-2.

- García Felguera, María Santos (1993). Las vanguardias históricas (y 2) (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- Gibson, Michael (2006). El simbolismo. Colonia: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-5030-5.

- González, Antonio Manuel (1991). Las claves del arte. Últimas tendencias (in Spanish). Barcelona: Planeta. ISBN 84-320-9702-0.

- Hofstätter, Hans H. (1981). Historia de la pintura modernista europea (in Spanish). Barcelona: Blume. ISBN 84-7031-286-3.

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (2002). Historia mundial del arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Akal. ISBN 84-460-2092-0.

- Laneyrie-Dagen, Nadeije (2019). Leer la pintura (in Spanish). Barcelona: Larousse. ISBN 978-84-17720-32-2.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1991). El arte simbolista (in Spanish). Barcelona: Destino. ISBN 84-233-2032-4.

- Morant, Henry de (1980). Historia de las artes decorativas (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpe. ISBN 84-239-5267-3.

- Souriau, Étienne (1998). Diccionario Akal de Estética (in Spanish). Madrid: Akal. ISBN 84-460-0832-7.

- Sturgis, Alexander; Clayson, Hollis (2002). Entender la pintura (in Spanish). Barcelona: Blume. ISBN 84-8076-410-4.

- Historia del arte 26. Vanguardias artísticas I (in Spanish). Barcelona: Salvat. 1991. ISBN 84-345-5361-9.