| Part of a series on |

| Violence against women |

|---|

| Killing |

| Sexual assault and rape |

| Disfigurement |

| Other issues |

| International legal framework |

| Related topics |

China has a history of female infanticide which spans 2,000 years. When Christian missionaries arrived in China in the late sixteenth century, they witnessed newborns being thrown into rivers or onto rubbish piles.[1][2] In the seventeenth century Matteo Ricci documented that the practice occurred in several of China's provinces and said that the primary reason for the practice was poverty.[2] The practice continued into the 19th century and declined precipitously during the Communist era,[3] but has reemerged as an issue since the introduction of the one-child policy in the early 1980s.[4] The 2020 census showed a male-to-female ratio of 105.07 to 100 for mainland China, a record low since the People's Republic of China began conducting censuses.[5] Every year in China and India alone, there are close to two million instances of some form of female infanticide.[6]

History

.jpg.webp)

Confucianism has an influence on female infanticide in China. The fact that male children work to provide for their elderly and that certain traditions are male-driven lead many to believe they are more desirable.[8]

19th century

During the 19th century, the practice was widespread. Readings from Qing texts show a prevalence of the term ni nü (to drown girls), and drowning was the most common method used to kill female children. Other methods used were suffocation and starvation.[lower-alpha 1][10] Exposure to the elements was another method: the child would be placed in a basket which was then placed in a tree. Buddhist nunneries created "baby towers" for people to leave a child.[11] In 1845, in the province of Jiangxi, a missionary wrote that these children survived for up to two days while exposed to the elements and that those passing by would ignore the screaming child.[12] Missionary David Abeel reported in 1844 that between one-fourth and one-third of all female children were killed at birth or soon after.[13]

In 1878 French Jesuit missionary, Gabriel Palatre, collated documents from 13 provinces[14] and the Annales de la Sainte-Enfance (Annals of the Holy Childhood), also found evidence of infanticide in Shanxi and Sichuan. According to the information collected by Palatre the practice was more widespread in the southeastern provinces and the Lower Yangzi River region.[15]

20th century

In 1930, Rou Shi, a noted member of the May Fourth Movement, wrote the short story A Slave-Mother. In it he portrayed the extreme poverty in rural communities that was a direct cause of female infanticide.[16]

One-Child Policy

In Chinese society, most parents preferred having sons, so in 1979 when the government created the One-Child Policy, baby girls were aborted or abandoned.[17] If parents had more than one child they would be fined. The earning potential of the male heir compared to a female made parents believe that having female children would be an economic hardship, making female infanticide more desirable solution.[8]

A white paper published by the Chinese government in 1980 stated that the practice of female infanticide was a "feudalistic evil".[lower-alpha 2] The state officially considers the practice a carryover from feudal times, not a result of the state's one-child policy. According to Jing-Bao Nie, it would be "inconceivable" to believe there is "no link" between the state's family planning policies and female infanticide.[18]

On September 25, 1980, in an "open letter", the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party requested that members of the party, and those in the Communist Youth League, lead by example and have only one child. From the beginning of the one-child policy, there were concerns that it would lead to an imbalance in the sex ratio. Early in the 1980s, senior officials became increasingly concerned with reports of abandonment and female infanticide by parents desperate for a son. In 1984, the government attempted to address the issue by adjusting the one-child policy. Couples whose first child is a girl are allowed to have a second child.[4] Even when exceptions were made to the One-Child Policy if a couple had a female child first, the baby girls were still discarded, because the parents didn't want the financial burden of having two children. They would continuously do this until they had a boy.

Current situation

Many Chinese couples desire to have sons because they provide support and security to their aging parents later in life.[19] Conversely, a daughter is expected to leave her parents upon marriage to join and care for her husband's family (parents-in-law).[19] In rural households, which as of 2014 constitute almost half the Chinese population,[20] males are additionally valuable for performing agricultural work and manual labor.[19][21]

A 2005 intercensus survey demonstrated pronounced differences in sex ratio across provinces, ranging from 1.04 in Tibet to 1.43 in Jiangxi.[22] Banister (2004), in her literature review on China's shortage of girls, suggested that there has been a resurgence in the prevalence of female infanticide following the introduction of the one-child policy.[23] On the other hand, many researchers have argued that female infanticide is rare in China today,[22][24] especially since the government has outlawed the practice.[25] Zeng and colleagues (1993), for example, contended that at least half of the nation's gender imbalance arises from the underreporting of female births.[24]

According to the Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF), the demographic shortfall of female babies who have died for gender-related issues is in the same range as the 191 million estimated dead accounting for all conflicts in the twentieth century.[26] In 2012, the documentary It's a Girl: The Three Deadliest Words in the World was released. It focused on female infanticide in India and China.[27]

According to China's 2020 census (the Seventh National Population Census of the People's Republic of China), the gender ratio of mainland China has improved, with the male-to-female ratio reaching a new record low of 105.07.[5] This is the most balanced gender ratio since the PRC began conducting a census in 1953.[5]

Female infanticides' effects on population and society

Female infanticide, especially as a result of the One-Child Policy, has caused an imbalance of genders and available females of childbearing age resulting in a decline in population and births. In 2017 there were under 13 birth per 1000 people. There were also 33 million more men than women.[28][29] The ratio imbalance between childbearing females and males because of female infanticide has also led to the rise of sex trafficking and bridal kidnapping of females or importing brides from other countries.[30]

Preventing female infanticide

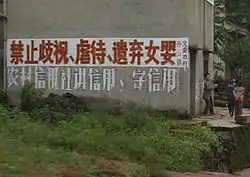

The Chinese government has enacted three laws to try to prevent future occurrences of female infanticide. The Mother and Child Health Care Law of 1994 prevented sex identification of the fetus and prohibited the use of technology for the use of selective abortions based on the fetus's sex in order to protect female infants.[30] The Marriage Law and the Women's Protection Law both prohibit female infanticide and protect women's rights.[8] There is also a campaign started called "Care for Girls" which gives financial support to female-only families and supports equality between the genders.[30]

Underreporting of female babies

In December 2016, researchers at the University of Kansas reported that the sex disparity in China was likely exaggerated due to administrative under-reporting and that delayed registration of females, instead of the abortion and infanticide practices. The finding challenged the earlier assumptions that rural Chinese villagers killed their daughters on a massive scale and concluded that as many as 10 to 15 million missing women hadn't received proper birth registration since 1982.[31][32] The underreporting is attributed to politics, with families trying to avoid penalties when girls were born, and local government concealing the lack of enforcement from the central government. This implied that the sex disparity of the Chinese newborns was likely exaggerated significantly in previous analyses.[33][34][35] Though the degree of data discrepancy, the challenge in relation to sex-ratio imbalance in China is still disputed among scholars.[36][37]

See also

- Female infanticide in India

- Femicide

- Gendercide

- It's a Girl: The Three Deadliest Words in the World

- List of administrative divisions in China by infant mortality

- List of Chinese administrative divisions by gender ratio

- Misogyny

- Missing women of China

- Sexism

- Sex-selective abortion § China

- Violence against women

- Women and religion

- Women in China

- Women in India

Footnotes

- ↑ "As soon as the little girls are born, they are plunged into the water in order to drown them, or force is applied to their bodies in order to suffocate them or they are strangled with human hands. And something even more deplorable is that there are servants who place the girl in the chamber pot or in the basin used for the birth, which is still filled with water and blood, and, shut away there, they die miserably. And what is even more monstrous is that if the mother is not cruel enough to take the life of her daughter, then her father-in-law, mother-in-law, or husband agitates her by their words to kill the girl."[9]

- ↑ "Infanticide through drowning and abandoning female babies is an evil custom left over from feudal times."[18]

References

- ↑ Milner 2000, pp. 238–239.

- 1 2 Mungello 2012, p. 148.

- ↑ Coale & Banister 1994, pp. 459–479.

- 1 2 White 2006, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 "China's latest census reports more balanced gender ratio - Xinhua | English.news.cn". 2022-07-05. Archived from the original on 2022-07-05. Retrieved 2022-07-05.

- ↑ "Hindu Bioethics, the Concept of Dharma and Female Infanticide in India Santishree Pandit", Genomics In Asia, Routledge, pp. 77–94, 2012-11-12, doi:10.4324/9780203040324-8, ISBN 9780203040324, retrieved 2023-04-18

- ↑ "Burying Babies in China". Wesleyan Juvenile Offering. XXII: 40. March 1865. Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 "BBC - Ethics - Abortion: Female infanticide". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ↑ Mungello 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Mungello 2008, p. 9.

- ↑ Lee 1981, p. 164.

- ↑ Mungello 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ Abeel 1844.

- ↑ Harrison 2008, p. 77.

- ↑ Mungello 2008, p. 13.

- ↑ Johnson 1985, p. 29.

- ↑ Kang, Inkoo (2019-08-09). "One Child Nation Is a Haunting Documentary About a Country's Attempts to Justify the Unjustifiable". Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- 1 2 Nie 2005, p. 50.

- 1 2 3 Chan, C. L. W., Yip, P. S. F., Ng, E. H. Y., Ho, P. C., Chan, C. H. Y., & Au, J. S. K. (2002). Gender selection in China: Its meanings and implications. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 19(9), 426-430.

- ↑ National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2014). Total population by urban and rural residence and birth rate, death rate, natural growth rate by region [Data set]. Retrieved from China statistical yearbook 2014 Archived 2015-11-26 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2 October 2019

- ↑ Parrot, Andrea (2006). Forsaken females : the global brutalization of women. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 53. ISBN 978-0742545793.

- 1 2 Zhu, W. X., Lu, L., & Hesketh, T. (2009). China’s excess males, sex selective abortion, and one child policy: Analysis of data from 2005 national intercensus survey. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 338(7700)

- ↑ Banister, J. (2004). Shortage of girls in China today. Journal of Population Research, 21(1), 19-45.

- 1 2 Zeng, Y., Tu, P., Gu, B., Xu, Y., Li, B., & Li, Y. (1993). Causes and implications of the recent increase in the reported sex ratio at birth in China. Population and Development Review, 19(2), 283-302.

- ↑ Female infanticide. (n.d.) Archived 2019-11-21 at the Wayback Machine BBC Ethics guide. Accessed 2 October 2019.

- ↑ Winkler 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ DeLugan 2013, pp. 649–650.

- ↑ Neuman, Scott; Schmitz, Rob (July 16, 2018). "Despite The End Of China's One-Child Policy, Births Are Still Lagging". npr.

- ↑ "Patriotism may hold key to China births challenge". South China Morning Post. 2018-06-19. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- 1 2 3 "Infanticide, Abortion Responsible for 60 Million Girls Missing in Asia". Fox News. 2015-03-25. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ↑ "It's a myth that China has 30 million "missing girls" because of the one-child policy, a new study says". Quartz. 29 November 2016.

- ↑ Denyer, Simon (30 November 2016). "Researchers may have 'found' many of China's 30 million missing girls". Washington Post.

- ↑ Shi, Yaojiang; Kennedy, John James (December 2016). "Delayed Registration and Identifying the "Missing Girls" in China". The China Quarterly. 228: 1018–1038. doi:10.1017/S0305741016001132. ISSN 0305-7410.

- ↑ Jozuka, Emiko (1 December 2016). "Study finds millions of China's 'missing girls' actually exist". CNN.

- ↑ Zhuang, Pinghui (30 November 2016). "China's 'missing women' theory likely overblown, researchers say". South China Morning Post.

- ↑ Cai, Yong (2017). "Missing Girls or Hidden Girls? A Comment on Shi and Kennedy's "Delayed Registration and Identifying the 'Missing Girls' in China"". The China Quarterly. 231 (231): 797-803. doi:10.1017/S0305741017001060. S2CID 158924618.

- ↑ den Boer, Andrea; M. Hudson, Valerie (9 January 2017). "Have China's Missing Girls Actually Been There All Along?". New Security Beat.

Bibliography

- Abeel, David (13 May 1844). "Infanticide In China". Signal of Liberty. Archived from the original on 8 January 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Coale, Ansley J.; Banister, Judith (1994). "Five decades of missing females in China". Demography. 31 (3): 459–479. doi:10.2307/2061752. JSTOR 2061752. PMID 7828766. S2CID 24724998. Archived from the original on 2020-01-01. Retrieved 2019-09-11.

- DeLugan, Robin Maria (2013). "Exposing Gendercide in India and China (Davis, Brown, and Denier's It's a Girl—the Three Deadliest Words in the World)". Current Anthropology. 54 (5): 649–650. doi:10.1086/672365. JSTOR 10.1086/672365. S2CID 142658205.

- Harrison, Henrietta (2008). "A penny for the little Chinese: The French Holy Childhood Association in China, 1843–1951" (PDF). American Historical Review. 113 (1): 72–92. doi:10.1086/ahr.113.1.72. S2CID 163110059. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-04. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- Johnson, Kay Ann (1985). Women, the Family, and Peasant Revolution in China. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226401898.

- Lee, Bernice J. (1981). "Female Infanticide in China". Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques. 8 (3): 163–177. JSTOR 41298766.

- Milner, Larry S (2000). Hardness of Heart/hardness of Life: The Stain of Human Infanticide. University Press of America. ISBN 978-0761815785.

- Mungello, D. E. (2012). The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442219755.

- Mungello, D. E. (2008). Drowning Girls in China: Female Infanticide in China since 1650. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742555310.

- Nie, Jing-Bao (2005). Behind the Silence: Chinese Voices on Abortion. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742523715.

- White, Tyrene (2006). China's Longest Campaign: Birth Planning in the People's Republic, 1949–2005. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0801444050.

- Winkler, Theodor H. (2005). "Slaughtering Eve The Hidden Gendercide" (PDF). Women in an Insecure World. Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2013-11-17.