Peak wheat is the concept that agricultural production, due to its high use of water and energy inputs,[1] is subject to the same profile as oil and other fossil fuel production.[2][3][4] The central tenet is that a point is reached, the "peak", beyond which agricultural production plateaus and does not grow any further,[5] and may even go into permanent decline.

Based on current supply and demand factors for agricultural commodities (e.g., changing diets in the emerging economies, biofuels, declining acreage under irrigation, growing global population, stagnant agricultural productivity growth),[6] some commentators are predicting a long-term annual production shortfall of around 2% which, based on the highly inelastic demand curve for food crops, could lead to sustained price increases in excess of 10% a year – sufficient to double crop prices in seven years.[7][8][9]

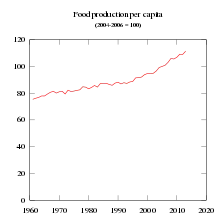

According to the World Resources Institute, global per capita food production has been increasing substantially for the past several decades.[10]

China

Water is a necessary input for food production. Two billion people face acute water shortage this century as Himalayan glaciers melt.[11] Water shortages in China have helped lower the wheat harvest from its peak of 123 million tons in 1997 to below 100 million tons in recent years.[12] But by 2020 production is back to 134Mt, see.[13] Of China's 617 cities, 300 are facing water shortages. In many, these shortfalls can be filled only by diverting water from agriculture. Farmers cannot compete economically with industry for water in China.[14] China is developing a grain deficit even with the over-pumping of its aquifers. Grain production in China has been said to have peaked in 1998 at 392 million tons, falling below 350 million tons in 2000, 2001, and 2002, although such was 571 million tons in 2011 after eight consecutive years of increase from 2003 to 2011.[15] The annual deficits have been filled by drawing down the country's extensive grain reserves, and by reliance on the world grain market.[16] Some predict that China will soon become the world's largest importer of grain.[17]

Figures from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) contradict many claims that the country's wheat supply is unstable. According to USDA, in 2014 China imported 1.5 million tonnes (MT) of wheat, and had relatively small exports of 1 MT. However, China produced 126 MT of wheat in 2014, according to the same source. For comparison, Egypt was 2014's largest importer, with imports of 10.7 MT. If China had imported more than Egypt, it still would have produced almost 10 times more wheat than it imported, while in fact it produced more than 100 times more.[18]

Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan

In 2022 Russia, Ukraine and Kazakhstan have restricted exports and levied tariffs on wheat. Higher prices are not meeting any opposition from desperate buyers.[19]

See also

- Other resource peaks

References

- ↑ IFDC, World Fertilizer Prices Soar, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2009-03-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Investing In Agriculture - Food, Feed & Fuel", Feb 29th 2008 at

- ↑ "Could we really run out of food?", Jon Markman, March 6, 2008 at http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/SuperModels/CouldWeReallyRunOutOfFood.aspx Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ McKillop, Andrew (2006-12-13). "Peak Natural Gas is On the Way - Raise the Hammer". www.raisethehammer.org. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ↑ Agcapita Farmland Investment Partnership - Peak oil v. Peak Wheat, July 1, 2008, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-20. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "The future of food and agriculture: Trends and challenges" (PDF).

- ↑ Globe Investor at http://www.globeinvestor.com/servlet/WireFeedRedirect?cf=GlobeInvestor/config&date=20080408&archive=nlk&slug=00011064

- ↑ Credit Suisse First Boston, Higher Agricultural Prices: Opportunities and Risks, November 2007

- ↑ Food Production May Have to Double by 2030 - Western Spectator "Food Prices Could Increase 10 Times by 2050 | WS". Archived from the original on 2009-10-03. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ↑ Agriculture and Food — Agricultural Production Indices: Food production per capita index Archived 2009-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, World Resources Institute

- ↑ Joydeep Gupta (2008-02-06). "Two billion face water famine as Himalayan glaciers melt". Indian Muslim News and Information. Archived from the original on 2009-04-02. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ Raja M (2006-07-21). "India grows a grain crisis". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 2006-08-19. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ "China Wheat production, 1960-2020". knoema.com. 2021-08-12. Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- ↑ Lester R. Brown and Brian Halweil (1998). "China's Water Shortage Could Shake World Grain Markets". Worldwatch Institute. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ Xinhua (2011-12-27). "China stresses stable grain production". China Daily. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ↑ Lester R. Brown (2002-08-09). "Water deficits growing in many countries - Water Shortages May Cause Food Shortages". Great Lakes Directory. Archived from the original on 2007-07-04. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ Lester Brown (2004-03-12). "China's Shrinking Grain Harvest". The Globalist. Archived from the original on 2009-04-04. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ "China Wheat Production by Year". Index Mundi. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Jon Markman (2008-03-06). "Could we really run out of food?". MSN Money. Archived from the original on 2011-07-17.