The German colonization in Rio Grande do Sul was a large-scale and long-term project of the Brazilian government, motivated initially by the desire to populate the south of Brazil, ensuring the possession of the territory, threatened by Spanish neighbors. In addition, the search for Germans intended to recruit mercenary soldiers to reinforce the Brazilian army. The immigrants would also be important to improve the domestic supply of basic goods, since they would settle on the land as owners of productive small farms. Furthermore, the Germans would help to "whiten" the Brazilian population.

An area of unclaimed land in the Sinos River valley was chosen for the settlement and the first settlers arrived in 1824. Throughout the 19th century and into the mid-20th centuries, tens of thousands more would arrive, either through government initiative or private entrepreneurship.

Overview

After a difficult start, being settled in a jungle region, many colonies prospered, although several remained stagnant for a long time. Others were not consolidated and their inhabitants dispersed. Within the rural colonies, urban centers were soon being formed, gathering the first schools, churches, administrative buildings, party halls, and a series of workshops, stores, small industries and manufactures.[1][2]

At the beginning of the 20th century, a large Germanic community had already formed in the state, with significant political, cultural, economic, and social expression, but this same empowerment was the cause of friction with the Portuguese-Brazilian population.[3] The interwar period was particularly difficult for the preservation of the socio-cultural identity of the German descendants, going through a period of repression and persecution resulting mainly from the nationalist campaign of Getúlio Vargas. The associations of many Germans with Nazism and Integralism made the dialogue with the government and the rest of society more complicated. After this crisis, new problems arose with the progressive decline of family farming, rural flight, and swelling of the cities.[4]

In 1974, when the 150th anniversary of the beginning of German colonization in the state was celebrated, the main traumas of Vargas' repression were overcome, and movements of cultural affirmation based on the immigrant's heritage and identity emerged in many cities, increasing the critical bibliography on the theme of immigration, overthrowing old myths that erected the immigrant as the prototype of a hero, and the Germans as a superior race, bringing light to previously unknown, obscure or contradictory aspects of the colonization process.[1][4]

Many memorialist narratives and genealogical studies have also appeared since then, and there is an effort of official bodies, communities and universities to rescue the heritage that time has erased. Aside from disputes and divergent discourses, it is a consensus that the Germans left a mark in the history of Rio Grande do Sul. They are the founders of numerous cities, some of them being regional poles today. The Germans brought many traditions, ways of thinking, and forms of coexistence, which enriched the socio-cultural panorama. Their descendants became renowned politicians, artists, scientists, and intellectuals, and founded countless associations, schools, social, sports, and recreational clubs, companies, and newspapers. Their contribution to the economic development of the state was significant, and their language is still heard in the daily life of many communities in the countryside. A rich collection of architecture, art and handicrafts from the early days survives, although a vast amount has disappeared due to neglect or under the urgencies of progress.[1]

History

Context

In colonial Brazil a productive system based on latifundia was built, where natural resources such as lumber were exploited, export monocultures such as sugarcane and coffee were developed, and cattle were raised extensively. The labor force was composed of slaves. After the installation of the Portuguese court in Rio de Janeiro in 1808, the royal house and liberal politicians began to develop plans to colonize the demographic voids in the south with free foreigners, who would be given small farms for the agricultural production of basic commodities, supplying the precarious domestic market. This population would also serve to swell the army in case of a border conflict with the neighboring Platinos, at a time when the Iberian powers' disagreements about the relations and limits between their American colonies had not yet been solved. Finally, they helped to fulfill the elites' desire to whiten the Brazilian population, which at that time was massively composed of blacks and indigenous. Immigrants would later fill the labor shortage on the coffee farms generated by the abolition of the slave trade.[5][1]

In the European continent a crisis was forming: With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, great masses of peasants became impoverished and left the countryside taking refuge in the cities and swelling the mass of proletarianized workers in factories, or were sent to the mines and railroads. Great political and social instability, successive and devastating wars, revolts, epidemics, and famine contributed to an unsustainable scenario. Thus, due to a series of factors, a vast wave of emigration began in which tens of millions of emigrants from various countries left for America, where they hoped to prosper.[5][2] According to Zuleika Alvin, "for some expelling countries, such as Italy and Spain, the descriptions of the places where the immigrants lived and the promiscuity in which they were forced to live due to poverty are good examples of the repercussion of the economic crisis on the bucolic landscape of the countryside". The researcher continues:[2]

"As it was being implemented, this process was releasing a surplus of labor that the late industrialization of countries like Italy and Germany, for example, could not absorb. This, coupled with a population growth never seen before, occurred in the nineteenth century, when the population of Europe increased two and a half times, the advance of technology, which allowed tasks previously performed by man to be performed by machines, and the unprecedented improvements in transportation, made available to the market a horde of landless and unemployed peasants." .

The crisis would drag on throughout the nineteenth century, and in the first decades of the twentieth century, due to new upheavals in Europe, many other emigrants would also leave.[5]

In Rio Grande do Sul there were areas where latifundia had not developed as they were located in regions unsuitable for extensive cattle raising, at the time the main economic activity of the province. The region of the Sinos River valley was then chosen to host the government's first colonizing venture in the south.[6] The south was a favorable region for several reasons: The landowners were not interested or did not look kindly at the idea of introducing free labor and a smallholding system, which could compete economically and shake the political and social power of the landowning elite. However, in the south, there was a large amount of idle wasteland, the so-called "demographic voids", which although populated by Indians, did not change anything in the eyes of the government.[7][8]

In the middle of the century, other factors contributed to the increase in the attractiveness of the south. When Germans began to be shipped to the coffee plantations in São Paulo, they became poorly paid employees, often encountered subhuman working and housing conditions, and suffered abuse. Reports circulated in Europe, causing outrage and leading to restrictions on the departure of Germans from some regions. The prospect of obtaining land and being a landowner remained open in the south. Finally, there was a scientific discourse circulating at the Court, which considered the North and Northeast unadvisable for the settlement of Europeans.[8][7]

Stage One

The Brazilian government, convinced of the benefits of immigration, sent in 1822 Major Georg Anton von Schäffer to Europe to recruit interested emigrants to Brazil. The major traveled first to Hamburg, negotiating contracts with the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin and then with Birkenfeld, belonging to the Duchy of Oldenburg.[3] To convince those interested, the Brazilian government offered a series of advantages: Transport at the government's expense; free land allotment of 78 hectares; a daily subsidy of one franc or 160 réis for each settler in the first year and half in the second; a certain amount of clothing, oxen, cows, horses, pigs, and chickens, in proportion to the number of people in each family; ten-year exemption from paying taxes; freedom of worship, and immediate granting of Brazilian citizenship. Some promises hurt the Empire's Constitution, such as freedom of worship and immediate citizenship, and the aid in materials and money did not always deliver what was promised. There are many accounts of settlers living the first years in misery.[6][8]

The first immigrants set sail on the sailing ship Protector from the port of Hamburg in March 1824. After passing through Rio de Janeiro, where they were received and reallocated by Monsignor Miranda, they arrived in São Leopoldo on July 18, 1824. They were then sent to the deactivated Real Feitoria do Linho Cânhamo, where they arrived on July 25, 1824. There were 39 people from nine families.[8] Also in 1824, with settlers not adapted in São Leopoldo, a colony was created in the village of São João, one of the former Sete Povos das Missões, but the initiative failed and the remnants were taken to São Borja. In 1826, the colonies of Três Forquilhas and Dom Pedro de Alcântara were created, but they were isolated and remained stagnant. In 1827, some families moved from São Leopoldo to Santa Maria. Between 1824 and 1828, Schaeffer reportedly brought about 4,500 soldiers and settlers to Brazil.[9] Their regions of origin were diverse: Hunsrück, Saxony, Württemberg, Coburg, Holstein, Hamburg, Mecklenburg, Hanover, Palatinate, Pomerania, and Westphalia.[10][11]

In 1830, when more than 5,300 Germans were already in the province, pressure from landowners led to the approval of a new Budget Law that prohibited any spending on colonization, including the payment of back debts. The law created difficulties for settlers who were establishing themselves, preventing them from receiving subsidies. The outbreak of the Ragamuffin War in 1835 divided the province and increased the difficulties for the continuity of the government's colonizing plans, worsened when Law nº 16 of 12 August 1834 had transferred to the province's the responsibilities for organizing the project. With these upheavals, the flow of immigrants was greatly reduced but not entirely interrupted, and the colonized areas increased. At the beginning of the war the German colonization already extended to the north of São Leopoldo with the formation of the nuclei of Hamburgo Velho, Dois Irmãos, Bom Jardim, Quarenta e Oito, and São José do Hortêncio.[8][9]

When the war ended, the flow intensified again and increased with the arrival of many emigrants who traveled on their own without integrating themselves into the government's project. Other waves were brought to settle private colonies, as was the case with the founding of the Colônia de Santa Maria do Mundo Novo, owned by Tristão José Monteiro, which gave rise to the cities of Taquara, Igrejinha, and Três Coroas, and the Colônia Padre Eterno, current Sapiranga, owned by the Baron of Jacuí. By the mid-century, more than eight thousand Germans had arrived.[12]

In this first stage of colonization, São Leopoldo and Hamburgo Velho were the most prosperous centers, favored by their proximity to Porto Alegre, the provincial capital, and by the control of an important network of land and river transport. In a few decades, these centers had become dynamic villages with well-structured commerce, an expressive rural production concentrated on maize, beans, manioc, and tobacco, as well as several manufactures and small industries. The surplus production supplied Porto Alegre and nearby regions and was exported.[12][13] The economic and urban growth provided for the formation of a new society and a differentiated culture in this region.[7] A German community was also formed in Porto Alegre, which by mid-century had almost two thousand members in a variety of trades and enterprises.[12]

Second Stage

The second stage of colonization begins with a series of adjustments in the legislation. In 1848, six leagues of unclaimed land in each province were designated for the exclusive purpose of colonization. In 1850, the new settlers became naturalized after two years of residence and were exempt from military service, except for the National Guard. In the same year, the privilege of free lots was abolished and a charge was levied for them. This law was superseded by provincial law in 1851 which authorized the return of free land distribution, but the average plot size dropped from 77 to around 49 hectares. Also in 1851 new recruiting agents were hired. The gratuity was abolished again in 1854 but the debt could be paid off in five years and subsidies in cash, tools, and seeds returned. In 1855, the assistance to immigrants during transportation was defined, and in 1857, the positions of interpreter-agent and butler-agent were created, in charge of receiving and treating immigrants in the capital and sending them to the colonies. The imperial government sought to transfer to the provinces all the responsibilities it could for colonization.[8][14]

In 1849, the colony of Santa Cruz do Sul was founded in the Rio Pardo valley, the first one entirely organized by the province, on the margins of the recently opened Estrada de Cima da Serra, which connected the important commercial warehouse and military base of Rio Pardo with the cowsheds of Soledade. Having Santa Cruz as a support base - it would become the main German colonial town in the central region of the province in this stage. The available fallow land soon ran out, even with the concession of new areas by the government, and several other settlements were opened by private individuals or their areas were bought from private individuals by the government. Starting colonies was advantageous for the owners of large idle land since the government offered incentives, and if well conducted the projects generated large profits.[8][14]

Between 1848 and 1874, more than 16 thousand new immigrants arrived, and in this period the population already living there increased rapidly since the settlers in general had many children. At the end of this period, all the valleys of the rivers Caí, Taquari, Pardo, Pardinho, Sinos, and part of Jacuí were occupied by Germans and their economy was expanding and diversifying, to the satisfaction of the government, which saw its long efforts rewarded. According to Olgário Vogt,[14]

"traveling through several cities and regions of Rio Grande do Sul, in 1871, the English journalist Michael Mulhall, established in Buenos Aires since 1858, found that in the province agriculture was, at that time, almost exclusively the responsibility of German settlers. They would constitute then, summing immigrants and their descendants, about 80 thousand people who were spread over 42 colonies, located especially in the valleys of the rivers Jacuí, dos Sinos, Caí, and Taquari. It was mainly due to these colonies that Rio Grande earned the title of "Barn of the Brazilian Empire".

Despite the overall positive outcome, the situation of individual cases varied significantly; many colonies faced difficulties, and unrest, or remained long decades with a subsistence economy.[14]

Between 1874 and 1889, more than 6 thousand immigrants entered the province, practically all under the direction of private individuals. The government at this time was more occupied with the beginning of Italian immigration, which from 1875 would bring a much larger contingent of immigrants than the total German immigration and would do so in much less time.[15]

Third Stage

With the Proclamation of the Republic in Brazil, the vacant lands passed to the states, as did the responsibility for colonization. The positivist local government defended spontaneous immigration and private colonization. Quickly, the Rio Grande do Sul plateau was transformed into a colonial zone due to the attracted by the possibilities of exploiting the land trade and obtaining easy profits.[16]

Between 1890 and 1914 another 17,000 Germans arrived. The colonization frontier at the beginning of the 20th century reached the northwest of the state, creating Ijuí, and Santa Rosa, among others, soon after crossing the Uruguay River and migrating to the west of Santa Catarina and Paraná, besides colonies in the north of Argentina and Paraguay. After the First World War, the colonial question returned to the control of the Union, and due to the dominant nationalist tendencies a limit was imposed on the entry of more foreigners. Even so, it is estimated that between 1914 and 1939 more than 30,000 Germans and Austrians arrived, but about a third of them did not settle permanently, moving to other states after a few years. Of those who stayed, a good part did not end up in the countryside or pioneer new settlements but preferred to settle in the already established cities.[7][17]

After World War II the number of immigrants decreased until it became extinct. The last colony formed was a group of Mennonite families who had emigrated to Santa Catarina in the 1930s, migrating to Rio Grande do Sul, settling south of Bagé between 1949 and 1951.

The rural colonies and communities

In the first stage, before the use of steamships, the immigrants' trip could take up to three months, but later it was generally completed in a month and a half. The ships were overcrowded, the accommodations were precarious, and hygiene was poor. After arriving in Brazil, they were distributed to the multiple areas of colonization scattered throughout the country. Those heading to Rio Grande do Sul followed in smaller boats to the port of Porto Alegre, from where they were shipped to the colonial regions. São Leopoldo was the main reception point for the new arrivals. Since the provincial fields were occupied by cattle raising, the immigrants settled in virgin forests. There, the task ahead of them was monumental, for everything had yet to be done. Most of the immigrants had been at least partly influenced by misleading government propaganda, which advertised Brazil as a wonderland, where people could get rich quickly.[18] According to Thomas Davatz:[19]

"Beautiful descriptions, attractive accounts of the countries that the imagination saw; pictures painted partially and inaccurately, in which reality is sometimes deliberately distorted, seductive and fascinating letters or reports from friends and relatives; the effectiveness of so many propaganda leaflets and also, above all, the untiring activity of emigration agents, more concerned with lining their own pockets than with easing the existence of the poor... - all this and more has contributed to the emigration issue reaching a truly sickening degree, becoming a legitimate emigration fever that has already contaminated many people. And just as physical fever dissipates calm reflection and clear judgment, a similar thing happens with emigration fever. He to whom it has infected dreams of the idealized country during sleep and wakefulness, at work and rest; he clings to prospectuses and pamphlets dealing with his favorite subject, giving them the greatest credit."

Slave labor was not allowed in the colonies, leaving all tasks to the family. There was the possibility of hiring helpers, but in the beginning this was unlikely due to the poverty of most immigrants.[20] Difficulties increased because government aid was irregular, scarcity of money, tools, and food was not uncommon, and they came completely unprepared for what they would find. They lived in rustic dwellings, did not know the particularities of the land and its requirements, about dangerous animals and poisonous plants, how to deal with human diseases and agricultural pests common in the country, and feared attacks from Indians and jaguars, and contrary to the habit of the village to which they were accustomed in Europe, in Rio Grande do Sul the families were isolated in each particular lot, communicating through precarious tracks that in rainy weather turned into mudflats.[20][21][22]

In 1850, Martin Buff, director of the Santa Cruz do Sul colony, wrote in his report: "For the people who come from Europe it is very difficult to get used to the bush in the early days, so they are always uncomfortable and sick."[22] There are numerous accounts from the newly settled about the fear they felt in front of the unknown world. Moreover, they did not master Portuguese and the Brazilian culture was foreign to them.[21] Not by chance the integration of German communities with the Portuguese-Brazilian universe was complex, time-consuming, and often tumultuous.[7]

Despite all these obstacles, the populated valleys had fertile land, which allowed more than one harvest per year for some crops, so that in a short time the harvests were significant and the surpluses could be sold, generating income. Techniques for clearing the forest, preparing the soil, and managing crops and livestock, more suitable to the local environment, were gradually learned from the caboclos and Brazilians, and helped to overcome the gradual loss of soil fertility after deforestation. Thus, within a few years, the settler in general could afford to build a bigger house and have a comfortable life. The agrarian techniques consolidated by the settlers in a few generations became the basis of the state's agricultural culture in this region for a long time.[20] As Marli Mertz stated:[20]

"The colonial agrarian system was constituted, above all, by a set of agricultural practices and techniques that were present throughout the history of agriculture in Rio Grande do Sul and designed its profile in such a way that these practices and techniques can still be found in regions of the state where small property and minifundios predominate coexisting with more advanced agricultural systems. In this sense, the colonial productive system used by the settlers continued to be practiced in the state after the end of its expansion zone. Even though there were no more fallow lands, they continued to practice their agriculture by burning and rotating the land during the 50s and 60s of the 20th century, practices that contributed to the agricultural crisis that was felt from then on."

The experience of land ownership was valuable to the settler, both from an economic, human, and social point of view - being the possibility of redemption from his former poverty not only a guarantee of basic survival, but a guarantee of a dignified life.[22][24] Josef Umann, one of the pioneers, reported in his memoir, "I believe that no king in his palace could feel happier than I once did in my first hut, which I knew to be mine, and even though it left something to be desired in every sense, we had the hope that over time it could be improved, and above all, we knew that no one could force us to abandon our dwelling."[24]

Besides being a human need, living in a community offered practical advantages to the settlers. Not being able to hire employees or use slaves, mutirão (joint efforts) was a systematic practice among the settlers, and marriages performed within the communities strengthened the bonds of trust and cooperation among families. In the rural colonies, small urbanized nuclei were soon formed, where the settlers scattered throughout the lots met and held their fairs to exchange products and experiences, their collective festivities, and their sports competitions.[7][20][25]

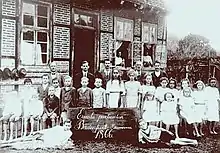

The Germans gained fame in the state as a people who cultivated education and the arts, and many of the family activities had an artistic character, such as singing and handicrafts. In these villages, chapels, schools, cemeteries, party halls, workshops in blacksmithing, cooperage, carpentry, and metalworking, as well as pottery, mills, tanneries, stills, breweries, tailoring, shoe repair, and other commercial establishments began to appear. These nuclei functioned as intermediaries and links between the colonies and the larger cities.[7][20][25]

As the community stabilized and related to the surrounding Brazilian people, nature, and the local ways of coexistence, a new folklore hybrid of German and native traditions emerged.[22] However, for the mentality of the time, from which the Germans did not escape, nature could be fascinating and generous, but it was also a barbaric and potentially dangerous element that needed to be dominated and disciplined so that it could serve man's purposes. This relationship of the conqueror over the environment, plus the hard work of clearing and cultivating the land, were important elements for the articulation of a founding myth supported by an exarcerbated patriotic discourse around the alleged superior virtues of the German settler as a civilizing hero, a discourse that began to be expressed as early as the mid-nineteenth century with the support of the native officialdom itself.[22][26]

The Baron de Homem de Mello, president of the province in 1868, in evaluating the impact of colonization, mentioned, "A short time ago there was only a void here, populated only by animals. Today this ground has been transformed and given over forever to civilized man due to the efforts of a people full of energy and religiosity."[22] This rhetoric would become influential in the process of social and identity affirmation of the German community, not only in the countryside,[7] and left a deep imprint on the classical historiography of immigration.[26]

After a period of broad expansion throughout much of the state, by the mid-twentieth century the old model of small rural property found itself on a seemingly dead-end path. The previous decades had been turbulent with the Vargas repression of foreigners and Brazil's entry into World War II against Germany.[4] However, in the face of modernization, accelerated urbanization, mechanization of farming, and industrialization, an entire productive system that had been in place since the 19th century was entering a crisis.[20][27] In Argemiro Brum's analysis,[20]

"the small property and the large family forced an intense use of the soil, which caused a rapid depletion of its natural fertility, in many cases reaching near exhaustion. These factors, added to the continuous transfer of income from farmers to traders and industrialists, through the difference in the price of products - low prices for agricultural products that the settler sold and higher prices for goods that the rural family acquired in commerce - explain the generalized stagnation and even decline of traditional agriculture. This situation became quite clear in the 1950s and became much worse in the 1960s, leading traditional agriculture to a stranglehold."

Moreover, the multiplication of colonies over a large territory, bringing with them intensive farming, has caused a serious ecological imbalance in the state, which has lost much of its forests and biodiversity. The mechanization of farming and the intensive use of pesticides in recent decades has increased environmental problems and generated political disputes, poverty, supply problems, and human diseases.[20][22][28] According to Silva Neto & Oliveira, "more recently, especially during the 1970s and 1990s, due to the idea that family farming was incapable of producing competitively, priority was given to patronage farming to the detriment of family farmers. Fortunately, important movements have been emerging, both among intellectuals and government officials at the federal and state levels, pushing to change this understanding."[27]

Colonial cities

With the proliferation of rural settlements, multiple points of urbanization emerged. It did not take long for the settlements to take on village proportions in several places, with the first lay religious brotherhoods, social clubs, sports, political and mutual aid associations,. A significant part of the immigrants were not farmers, but urban laborers and specialized professionals. Between 1824 and 1845, 60% of the men in São Leopoldo were artisans, industrialists, merchants, etc.[1][25]

The Germans were responsible for the creation of new municipalities in a large part of the Rio Grande do Sul territory. Most of these emancipated themselves with small territorial areas. Between 1954 and 1965, 140 new municipalities were created. According to Silva Neto & Oliveira, "this process is the expression of the economic, social and political dynamics of the colonization of the state's forest areas. As the occupation of the forests advanced through the countryside of the state, it was accompanied, gradually and rapidly, by the emergence of villages and the subsequent formation of new municipalities. [...] The high population density that accompanied the process of occupation of the bush lands by farmers' families represented a decisively influential factor in the dynamics of rural development."[27]

In the capital, in the first decades of the 20th century, the German presence was relevant, including an influential elite and several associations and clubs.[29][30] Karl von Koseritz left a deep mark on the metropolitan culture and press at the end of the 19th century.[31] Soon after, Pedro Weingärtner was acclaimed as the greatest painter of his generation in the state,[32] and business families such as the Renners, Gerdau, Bins, Johannpeter, Neugebauer, Möller, and others were beginning their heyday.[33]

This Germanic elite was a major financier of a cycle of architectural renovation in Porto Alegre, building a series of residential palaces and imposing bank and business headquarters. The positivist government stimulated this development, being itself engaged in a renovation and urban beautification of the central area of the city, in order to make it the "business card" of the state, eager to present itself as civilized and progressive and to gain more political space on the national scene. Under official auspices several public buildings of palatial dimensions and sumptuous decoration were built. The changes also accompanied new concepts of urbanism, habitability and sanitation. Theodor Wiederspahn, architect; Rudolf Ahrons, builder; and João Vicente Friedrichs, decorator, all German, were the protagonists of this movement.[34][35]

Despite the interest in self-affirmation and individualization, at the beginning of the 20th century, the process of acculturation to Brazilianness was already accelerating in the main colonial centers, and although the use of German still predominated in everyday life, most of the colonies were already bilingual and had many Brazilian households. Possibly partly due to the perception that the German legacy was beginning to be dissolved and threatened, singing, gymnastic, and shooting societies and other German cultural associations multiplied in numerous colonial cities and towns, and contact with Germany became frequent. German heroes and illustrious figures were the subject of tributes and monuments, and gave names to schools and streets; German artists, especially musicians, poets, and writers, were venerated in concerts, theaters, and soirees, and pamphlets in German had a wide audience.[7]

In the earliest historiography of immigration, the transformation of the threatening jungle into prosperous and civilized cities by the valiant arm, steady heart, and high spirit of the settler was a common depiction. In some of the publications, the German was compared to the Paulistan bandeirante, another romanticized image of the intrepid trailblazer, but being superior since he belonged to a "master race". This emphasis on the ethnic issue would be sharpened with the rise of Nazism in the 20th century, to which many German-Brazilians would adhere.[7]

However, Getúlio Vargas' rise to power signified a radical turn in the government's approach to the colonial matter. If until then the Germans had been favored – and had been the preferred people for the government in all settlement projects – now their empowerment generated fears among both the ruling elites and the population at large, and they came under suspicion as different right-wing currents vied for power.[30] This change did not happen suddenly, but when it was institutionalized by the Vargas state it had a severe impact. Since the beginning of the century, some intellectuals were already raising the question of the "German danger," there were conspiracy theories in vogue claiming that the German Empire intended to conquer America or at least annex southern Brazil, and by the beginning of World War I, the much talked about but never proven "German danger" had become, according to René Gertz, "an everyday thing, at least for more or less informed Brazilians."[4]

The spread of Nazi and Integralist ideologies among many German-Brazilians caused concern at a time when the government was trying to eliminate internal schisms, and there was suspicion that Nazis in Germany were trying to interfere in Brazilian internal affairs through covert agents; they were even suspected of having participated in the attempted coup of Integralism led by Plinio Salgado in 1938.[4][29][30]

Nazism would have a legion of sympathizers in Brazil, but although Vargas and other high authorities were also sympathetic to it - and Germany an important commercial partner - at the beginning of World War II, the government finally preferred to align itself with the United States, and Nazism in Brazil was repressed.[4][29][30]

Politics was only one of the aspects unfavorable to the Germans. Getúlio Vargas also directed his government program toward a large-scale homogenization of Brazilian society under the banner of Lusophony and the promise of social peace. A forced nationalization and acculturation of ethnic and cultural minorities was imposed throughout the country. For many at that time, the multiple colonies of foreigners that flourished freely throughout the national territory were anomalies and cysts in the social fabric that needed to be dissolved, as they threatened the cohesion of the nation and, with their differences, disrupted the harmony and integration of society.[4][29][30]

The Vargas regime was authoritarian, the rhetoric used at the time made vehement appeals to irrational fears of the population, conspiracy theories, and the emotional aspects of nationalism, and a wave of persecution, violence, humiliation, and censorship was unleashed not only against Germans but also against Italians, Japanese and other groups that until then had been considered valuable collaborators in the national progress. Schools and newspapers were closed, travelling required safe conducts, and German recreational and cultural associations were put under surveillance or banned.[4][29][30]

Brazil's entry into World War II against Germany and the Nazi-fascist bloc aggravated the pressure and censorship against German culture and speech in the region.[4][29][30] As researcher Ana Maria Dietrich summarized, "within the project of nationalization of Brazil desired by Vargas, the German changes from an ideological danger, due to the dissemination of Nazi ideology, to an ethnic danger, as an alien to the 'New Man' that one wished to build. With Brazil's entry into World War II in 1942, alongside the Allies, the danger becomes 'military and ideological'"[30] From 1942 on there were acts of violence against individuals and depredation in several cities, particularly Pelotas and Porto Alegre, against German establishments.[4] And according to Gertz,

"There are reports that police and patriots went through the colony intimidating its inhabitants to buy pictures of Brazilian personalities, at exorbitant prices. The confiscation of radios, books, and records as supposed instruments of Nazi propaganda took place, but objects that had no political or ideological connotation or were specific to a certain 'ethnic group' (such as art books and stamp collections) were also confiscated, not to mention the confiscation of motorcycles, which, on the same day, were sold to third parties by the policemen who had taken them from their owners. Recreational and cultural societies were often taken over by the state and became home to police or military forces to guarantee the 'nationalization' process. Persecution and physical and psychological torture by the police occurred in large numbers, including some deaths.[...] Although they were not mass internment sites - like the concentration camps in Germany - there were places of confinement for 'Axis subjects' all over Brazil, from Pará to Rio Grande do Sul. [...] The intensity of violence institutionalized or practiced by citizens in default of the state apparatus was influenced by local situations, depending on the ability of the local leaderships to circumvent, or not, confrontations, but also on the posture of the authorities."

Postwar period

After the German defeat, the German population in Rio Grande do Sul sought to reorganize itself and the leaderships quickly articulated themselves. In 1947, about 30% of the elected state deputies had a German surname, a percentage that was much higher than the proportion of Germans in the society. In the following year, the return of property confiscated during the War was demanded in the Legislative Assembly. In 1949, the 25th of July, the date of the arrival of the first immigrants to the state, could already be publicly celebrated with the presence of the state governor, and in 1950 a German was candidate for governor. In 1951, the first 25 de Julho Cultural Center was founded in Porto Alegre, which would serve as a model for the creation of several others throughout the state, acting as poles for the cultivation of culture, art, language, and traditions.[36]

.tif.jpg.webp)

However, at the same time, there was a desire to become "Brazilianized" in institutions and groups, and many families voluntarily discontinued the use of the language at home because of the old prejudices that persisted against Germanness, and according to René Gertz, constraints of different kinds would persist for many years, "a fact that can be seen, for example, in the frequency with which, until the 1960s, the expression 'potato German' ("alemão batata") was used to curse people".[36] Gertz also stated that "the effects of the War on the population of German origin in the Rio Grande do Sul extend to the present day, when not only public opinion, common sense, but even state agents start from the seemingly obvious assumption that a phenomenon called 'neo-Nazism' can only be the exclusive product of the German colony."[4]

In this period, the economic emphasis also shifted and national culture diversified under the influence of globalization, modernization, and mass culture. The more prosperous and industrialized German cities swelled with large waves of immigrants from different parts of the state and the country, many of them exiled from the countryside by the crisis in the agricultural sector, who arrived in search of job opportunities. A large part of this new population had other ethnic and cultural backgrounds, did not speak German and had little interest in their history. All these factors concurred to shake the identity construction of the community, until then largely based on Germanness, and contributed to the German legacy being surrounded by prejudice.[7][29]

Recent years

A resumption in the affirmative discourse occurred during the celebrations of the 150th anniversary of colonization in 1974,[36] when many cities erected monuments and promoted festivities and publications, occurring at the same time a true explosion in the academic bibliography on immigration, in which many old myths were overthrown and other aspects were reinterpreted, But since then the maintenance of the sociocultural identity of the German descendants, as well as the recovery of their historical heritage, their oral memory and their material patrimony, have been complex processes, negotiated with difficulty among the different sectors of the society, today very different from what it was in the 19th and 20th centuries.[7][37][38] According to Professor Martim Dreher: "We have almost no studies about the peasantry, nor about the presence of the immigrant in urban centers, nor about childhood. In turn, gender studies are almost absent, and linguistic studies are incipient. The daily life of the populations is unknown."[39]

Despite these gaps, a significant number of cultural centers, museums, and archives seek to study, preserve, and disseminate the German legacy, with several historical buildings in colonial cities having been listed.[40][41][42] The Oktoberfest of Santa Cruz do Sul is one of the largest Germanic festivals in the state and since 2006 an official Cultural Heritage event of Rio Grande do Sul.[43] The Romantic Route includes 13 municipalities of German tradition, counting with an expressive heritage, monuments, museums, festivals, and other attractions related to the history and popular culture of the region.[44]

The important contribution of Germans to the formation and growth of the Rio Grande do Sul society is widely recognized. They were responsible for the inauguration of the footwear, textile, and metallurgical sectors.[45] They were firmly established in trade and industry, especially in the production of textiles, canned goods, beverages, confectionery, wood, leather, machinery, tobacco, glass, paper, soap, fertilizers, and chemical-pharmaceutical products,[46] and left valuable contributions in the fields of literature, press, politics, sports, education, religion, architecture, arts and crafts, and cuisine, among others.[45][46]

According to Lúcio Kreutz, "the studies that deal with German immigration in Rio Grande do Sul are practically unanimous in pointing out some aspects to which this ethnic group gave special attention. These are the community school, diffusion of the press, emphasis on associativism, organization of religious communities, creation of support structures to energize and channel local and regional initiatives, linking them to a common project."[47] He also states that "the great legacies of German immigration, visible even today, are found in the community organization of the colonial nuclei; in the associativism and the sports recreation; in the development and diversification of the commerce and industry of Rio Grande do Sul; in the enlargement of the religious spectrum of the province with the coming of thousands of protestants; in the development of a critical and pulsating press; and the investment and valuation of education understood as a mechanism of citizen formation".[48]

Currently, around a third of the people from Rio Grande do Sul have German ancestry.[48] The state has the largest population of German origin in Brazil and many communities still maintain a strong ethnic culture.[41]

Press and literature

To meet the reading and educational needs of the settlers, a local press was soon established. The first known work was the alphabet book for students Neuestes ABC Buchstabier und Lesebuch, printed in 1832 at Claude Dubreuil's print shop in Porto Alegre. There is no record of other didactic materials until the end of the 19th century when the Catholic and Lutheran churches became interested in the subject, and other publications began to proliferate.[49] Almanacs were very popular, offering a variety of information on daily life, agricultural techniques, astrology, weather forecasts, medical and hygiene notions, calendars, eclipse and moon phase forecasts, cultural and social news, anecdotes, obituaries, advertisements, religious teachings, novels, and others. Notable in this genre was the Deutscher Kalender, founded in 1854, the Koseritz Deutsche Volkskalender (1873), and the Kalender für Deutschein Brasilien (1881).[50][51]

In 1836, the pamphlet O Colono Alemão was published by Hermann von Salisch, advertising the Ragamuffin cause to the German settlers, and despite plans to be bilingual, it was published only in Portuguese and closed its activities the same year due to economic problems.[51] The first German language newspaper was Der Kolonist, which appeared in Porto Alegre in 1852, but closed the same year due to lack of receptivity. The following year Der Deutsche Einwanderer appeared, which operated precariously. The first to be successful was the Deutsche Zeitung, founded in 1861, and operating until 1917. By the end of the 19th century, the German press was well developed, with several newspapers competing for readers, such as Boten von São Leopoldo, Deutsches Volksblatt, Deutsche Post, Koseritz Deutsche Zeitung, and several others.[53]

Even with the censorship phase during the Vargas government, the German press played an important role in the history of the press in Rio Grande do Sul, covering a great diversity of demands and audiences. Newspapers were founded focusing on religious, political, technical, educational, and other subjects, besides the almanacs, which were extremely successful.[39] According to Greicy Weschenfelder, "the German press in Rio Grande do Sul had the function of social identification; it put in relation the several immigrant nuclei in the maintenance of the Germanic culture; it reinforced both the Catholic and Protestant values; and it was a mean for the immigrants to have more political participation in the state. [...] Whatever the disagreements of the German descendants of the immigrants, it was the journalists who gave them a collective consciousness, who enunciated the German-Brazilian problem and who proposed solutions."[53]

Some literary works have tried to portray German immigration in Rio Grande do Sul, such as A Ferro e Fogo by Josué Guimarães and Videiras de Cristal by Luiz Antônio de Assis Brasil.

German language

After the period of nationalism by Getúlio Vargas that prohibited the use of minority languages, even in a family environment, those languages still managed to survive despite the threats, coercion, imprisonment, and even torture. The speakers of dialects of German suffered, including Yiddish (a Germanic Indo-European language belonging to the High German linguistic group, spoken primarily and traditionally by Jews in Central and Eastern Europe).

The dialect formally called Riograndenser Hunsrückisch, a Germanic dialect originating from the Hunsrück region in the Rhineland-Palatinate state, prevailed. Dialects from neighboring regions such as Bavaria and Swabia also influenced the common South Brazilian German.[54]

Another specific form of the German language that has a history related to Rio Grande do Sul and other parts of Brazil is Pomeranian (Pommersch, Pommeranisch). This is a language native to the Nordic regions around the Baltic Sea and belongs to the Low German or Low Saxon family (Plattdeutsch, Plattdüütsch). In Brazil, Pomeranian came to be part of several communities in the states of Espírito Santo, Paraná, Minas Gerais, Rondônia, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul.[55][56]

Several Germanic dialects are part of the daily life of communities scattered throughout the state of Rio Grande do Sul in a greater or lesser degree of use. In a process of revitalization, and through a strong appeal by German-speaking Brazilians for the adoption of the German language as the official vernacular of cities colonized by Germans, Hunsrückisch was adopted as the co-official language in the municipalities of Barão[57] and Santa Maria do Herval,[58] and Pomerano became co-official in Canguçu.[59] In 2000, Hunsrückisch was included in IPHAN's National Inventory of Linguistic Diversity,[60] and in 2012 it was declared a Historical and Cultural Heritage of Rio Grande do Sul.[61] Santa Cruz do Sul declared Standard German as a Cultural Heritage of the municipality in 2020.[62]

German is the second most widely spoken foreign language in the state[63] and is offered in schools in many municipalities, such as Nova Petrópolis (Hunsrückisch),[64] Nova Hartz (Hunsrückisch),[65] Santa Maria do Herval (Hunsrückisch),[58] Canguçu (Pomeranian),[66] Estância Velha (Hunsrückisch ), Dois Irmãos, Ivoti, Morro Reuter, Feliz, Forquetinha, Lajeado, Venâncio Aires, Santa Cruz do Sul, Santo Cristo, Salvador das Missões, Campina das Missões and others.[67] Rio Grande do Sul has the largest number of schools with German teaching, and several actions being developed to promote the language, including theater, film, radio programs, meetings, documentaries, literary contests, and others.[68]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Arendt, Isabel Cristina; Witt, Marcos Antônio; Weimer, Günther (2013). "A imigração alemã no Rio Grande do Sul". Cinco séculos de relações brasileiras e alemãs. Instituto Martius-Staden / Goethe-Institut São Paulo. Editora Brasileira de Arte e Cultura.

- 1 2 3 Alvin, Zuleika (2010). "Imigrantes: a vida privada dos pobres do campo". In Novais, Fernando A. (ed.). História da Vida Privada no Brasil. Vol. 3, República: da Belle Époque à Era do Rádio (in Portuguese). Vol. 3:República: da Belle Époque à Era do Rádio. Companhia das Letras. pp. 215–287.

- 1 2 Mühlen, Caroline von (2010). "Sob o olhar dos viajantes: a colônia e o imigrante alemã no Rio Grande do Sul (século XIX)". Métis — História e Cultura. 9 (7).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Gertz, René E. (2015). "A Segunda Guerra Mundial nas regiões de colonização alemã do Rio Grande do Sul". Licencia&acturas. 2 (2).

- 1 2 3 Vogt (2006, pp. 79–82)

- 1 2 Vogt (2006, pp. 85–86)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Seyferth, Giralda (1994). "A identidade teuto-brasileira numa perspectiva histórica". In Mauch, Cláudia; Vasconcellos, Naira (eds.). Os Alemães no sul do Brasil: cultura, etnicidade, história (in Portuguese). Editora da ULBRA. pp. 11–28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gedoz, Sirlei T; Ahlert, Lucildo (2001). "Povoamento de desenvolvimento econômico na região do vale do Taquari, Rio Grande do Sul 1822 a 1930" (PDF). Revista Estudo & Debate. 8 (1).

- 1 2 Vogt (2006, pp. 87–89)

- ↑ "História - Colonização - Alemães". RS Virtual (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2007.

- ↑ Willems, Emílio (12 July 2013). "Procedência dos alemães que emigraram para o Brasil". Deutsche Welle (in Portuguese).

- 1 2 3 Vogt (2006, pp. 90–94)

- ↑ Rückert, Fabiano Quadros (2013). "A colonização alemã e italiana no Rio Grande do Sul: uma abordagem na perspectiva da História Comparada". Revista Brasileira de História & Ciências Sociais. 5 (10).

- 1 2 3 4 Vogt (2006, pp. 94–113)

- ↑ Vogt (2006, pp. 115–116)

- ↑ Neumann, Rosane Marci (2009). Uma Alemanha em miniatura: o projeto de imigração e colonização étnico particular da Colonizadora Meyer no noroeste do Rio Grande do Sul (1897-1932) (in Portuguese). PUCRS.

- ↑ Vogt (2006, pp. 116–125)

- ↑ Vogt (2006, pp. 128–129)

- ↑ Davatz, Thomas (1980). Memórias de um colono no Brasil: 1850 (in Portuguese). Belo Horizonte: EDUSP. pp. 47–48.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Mertz, Marli (2004). "A agricultura familiar no Rio Grande do Sul — um sistema agrário colonial". Ensaios FEE. 5 (1): 277–298.

- 1 2 Vogt (2006, pp. 129–139)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bublitz, Juliana (2011). "História ambiental da colonização alemã no Rio Grande do Sul: O avanço na mata, o significado da floresta e as mudanças no ecossistema". Tempos Históricos. 15 (2).

- ↑ Tarasantchi, Ruth Sprung (2009). "O Pintor Pedro Weingärtner". Pedro Weingärtner: um artista entre o Velho e o Novo Mundo (in Portuguese). Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo. pp. 22–23.

- 1 2 Umann, Josef (1997). Memórias de um imigrante boêmio (in Portuguese). EST/Nova Dimensão. p. 56.

- 1 2 3 Vogt (2006, pp. 169–173)

- 1 2 Witt, Marcos Antônio (2008). "Em busca de um lugar ao sol: anseios políticos no contexto da imigração e da colonização alemã (Rio Grande do Sul - século XIX". PUCRS: 27–29.

- 1 2 3 Oliveira, Angélica de; Silva Neto, Benedito (2008). "Agricultura familiar, desenvolvimento rural e formação dos municípios do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul". Estudos Sociedade e Agricultura. 16 (1).

- ↑ Gerhardt, Marcos (2011). "Colonos ervateiros: história ambiental e imigração no Rio Grande do Sul". Esboços: Histórias em contextos globais. 18 (25): 73–95.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Konrath, Gabriela (2009). O Município de Novo Hamburgo e a Campanha de Nacionalização do Estado Novo no Rio Grande do Sul (PDF) (in Portuguese). UFRGS. pp. 17–52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Haag, Carlos (2007). "Entre a feijoada e o chucrute". Revista Pesquisa Fapesp (40).

- ↑ César, Guilhermino (1967). "Koseritz e o Naturalismo". Organon. 12 (12).

- ↑ Ferreira, Athos Damasceno (1971). Artes Plásticas no Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). Globo. pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Rockenbach, Sílvio Aloysio (21 July 2013). "Porto Alegre, 'a cidade dos alemães' durante um século". Portal Brasil-Alemanha (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Weimer, Günter (2004). Arquitetura Erudita da Imigração Alemã no Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). pp. 43–71.

- ↑ Pesavento, Sandra J (1994). "De como os alemães tornaram-se gaúchos pelo caminho da modernização". In Vasconcellos, Naira; Mauch, Cláudia (eds.). Os Alemães no sul do Brasil: cultura, etnicidade, história (in Portuguese). Editora da ULBRA. pp. 199–208.

- 1 2 3 Gertz, René Ernaini (2015). "Descendentes de alemães no Rio Grande do Sul após a Segunda Guerra Mundial" (PDF). XXVIII Simpósio Nacional de História.

- ↑ Arnaut, Jurema Kopke Eis; Seixas, Ana Luisa Jeanty de (2014). "Gestão das áreas de entorno de bens tombados: estudos de caso nas cidades gaúchas de Piratini e Novo Hamburgo". V Seminário Internacional Políticas Culturais. Fundação Casa de Rui Barbosa.

- ↑ Manenti, Leandro; Stocker Júnior, Jorge Luis. Novo Hamburgo: o patrimônio arquitetônico da cidade industrial (in Portuguese). IPHAN.

- 1 2 Dreher, Martin (2007). "Como entender a cultura alemã no Rio Grande do Sul?". Revista do Instituto Humanitas — Unisinos (245).

- ↑ Neumann, Rosane Marcia; Meyrer, Marlise Regina; Gevehr, Daniel Luciano (2016). "Operações de memória e identidade étnica: a musealização da imigração alemã no Rio Grande do Sul" (PDF). Diálogos Latinoamericanos (25): 195–212.

- 1 2 Dilly, Gabriela; Gevehr, Daniel Luciano (2006). "Narrativas Museográficas da Imigração e Colonização Alemã como Espaços de Investigação da História: Possibilidades de Leitura" (PDF). Anais do I Seminário Internacional de Educação; III Seminário Nacional de Educação e I Seminário PIBID/FACCAT.

- ↑ "Bens tombados e em processo de tombamento" (PDF). IPHAN.

- ↑ "Oktoberfest - Edição Digital - 2020". Procultura - Governo do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Dhein, Cíntia Elisa; Porto, Patrícia Pereira (2012). "O Patrimônio de Imigração Alemã na Rota Romântica - RS" (PDF). Anais do VII Seminário de Pesquisa em Turismo do Mercosul.

- 1 2 Marten, Zelmute (29 July 2014). "A imigração alemã e a pluralidade do povo gaúcho". Governo do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese).

- 1 2 Piassini (2017, pp. 40–56)

- ↑ Vasconcellos, Naira (1994). "Escolas da imigração alemã no Rio Grande do Sul: perspectiva histórica". In Vasconcellos, Naira; Mauch, Cláudia (eds.). Os Alemães no Sul do Brasil: cultura, etnicidade e história (in Portuguese). Editora da ULBRA. p. 153.

- 1 2 Piassini (2017, pp. 40–56)

- ↑ Kreutz, Lúcio (2007). "Periódicos na literatura educacional dos imigrantes alemães no RS (1900-1939)" (PDF). 30ª Reunião Anual da ANPED.

- ↑ Piassini (2017, p. 52)

- 1 2 Leite, Carlos Roberto Saraiva da Costa (9 February 2016). "A imprensa alemã no sul do Brasil". Observatório da Imprensa (in Portuguese).

- ↑ Damasceno, Athos (1962). Imprensa Caricata do Rio Grande do Sul no Século XIX (in Portuguese). Globo. pp. 44–61.

- 1 2 Weschenfelder, Greicy (2010). Mestrado. "A imprensa alemã no Rio Grande do Sul e o romance-folhetim". PUCRS: 39–47.

- ↑ Ehrardt, Mirelle Araujo (29 April 2021). "Você conhece o Hunsrückisch?". Programa de Educação Tutorial — Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina.

- ↑ Schubert, Arlete; Kuster, Sintia Bausen; Hartuwig, Adriana Vieira Guedes (2010). "Programa de Educação Escolar Pomerana — PROEPO: Considerações sobre um Programa Político-Pedagógico voltado à Manutenção da Língua Pomerana no Espírito Santo". Pró-Discente: Caderno de Produção Acadêmico-Científica do PPG em Educação. 16 (2).

- ↑ Ebel, Daniele (6 December 2019). "Pomerano: uma língua brasileira". Tesouro Linbguístico — UFPel (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Lei Ordinária 2451 2021 de Barão RS". Leis Municipais (in Portuguese). 29 May 2021.

- 1 2 Altenhofen & Morello (2018, pp. 185–186)

- ↑ "Bancada PP comenta cooficialização pomerana". Canguçu em Foco (in Portuguese). July 2010.

- ↑ "Inventário do Hunsrückisch". Instituto de Letras da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul / Christian-Albrecht-Universität de Kiel (in Portuguese). Projeto Atlas Linguístico-Contatual das Minorias Alemãs na Bacia do Prata.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Modelli, Laís (6 May 2019). "A herança da imigração na fala do brasileiro". Deutsche Welle (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Aprovada a lei que oficializa a língua alemã como patrimônio cultural do município". Câmara de Vereadores de Santa Cruz do Sul (in Portuguese). 5 October 2010.

- ↑ Blum, Rodrigo W (23 July 2015). "Wir lieben die deutsche Sprache". Notícias Unisinos (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Aprovado projeto que incentiva o ensino da Língua Alemã no Ensino Médio de Nova Petrópolis". Câmara de Nova Petrópolis (in Portuguese). 23 February 2022.

- ↑ "Dialeto de origem alemã passa a fazer parte da grade escolar de Nova Hartz". Jornal Repercussão (in Portuguese). 7 March 2019.

- ↑ "Brasileiros da região pomerana tentam manter língua-mãe viva". Agência Brasil (in Portuguese). 8 January 2021.

- ↑ Altenhofen & Morello (2018, pp. 163–164)

- ↑ Altenhofen & Morello (2018, p. 201)

Bibliography

- Altenhofen, Cléo Vilson; Morello, Rosângela (2018). "Inventário do Hunsrückisch como Língua Brasileira de Imigração (IHLBrI)" (PDF). Instituto de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Política Lingüística / Projeto ALMA-H (Atlas Linguístico-Contatual das Minorias Alemãs na Bacia do Prata: Hunsrückisch / Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (in Portuguese).

- Piassini, Carlos Eduardo (2017). Imigração Alemã e Política: os deputados provinciais Koseritz, Kahlden, Haensel, Brüggen e Bartholomay. Assembleia Legislativa do Rio Grande do Sul.

- Vogt, Olgário Paulo (2006). Doutorado. "A colonização alemã no Rio Grande do Sul e o capital social". UNISC: 79–82.