Italian immigration in Rio Grande do Sul was a process in which Italians emigrated to the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, through both private and government initiatives.

Overview

Immigration began is a smaller scale and spontaneously between the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th, gaining intensity in the period from 1875 to 1914, when, through a colonizing program of the Brazilian government, eighty to one hundred thousand Italian immigrants entered the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Most were fleeing famine, epidemics, and wars in Italy, and lived as farmers. The program aimed to populate demographic voids, whiten the population, and establish a productive system based on small farms, with a free and landowning labor force that could supply the internal market with agricultural products.[1][2][3]

The project faced many difficulties and periods of tension and social turbulence but was generally successful. The immigrants founded several cities and significantly increased rural production, making the Italian colonial zone economically the second most important in the state by the beginning of the 20th century. Meanwhile, they created a new culture, adapting their millenary traditions to a new environment. In the cities, the economy was widely diversified. A wealthy elite was formed, which promoted an erudite culture, founded associations and clubs, and lived in urban palaces, supported by a mass of marginalized proletarians, many of them coming from the countryside.[1][2][3]

Despite the inequalities that soon manifested themselves in colonial society, since the early twentieth century the signs of progress became evident, a "work ethic" guided customs, and an apologetic discourse was articulated around the alleged qualities of the Italian, presenting them as civilizing heroes, creators of wealth, and models of virtue. This enthusiasm, supported and encouraged by the native officialdom, was interrupted during the Vargas Era, due to a nationalizing program and the state of war with Italy, situations that cast a pall of repression over the Italian language and culture of the region. In this period the emphasis on production also changed, industry and commerce assumed primacy, and those who had remained in the countryside suffered the consequences of the decline of the agricultural sector, starting a great exodus to the city, to other colonies, and other states.[1][2][3]

In the 1950s, after the repression, a process of reconciliation of the Italians and their descendants with the Brazilians began as well as a wide transition, not only to a new economic model but also regarding customs. A phase of rapid loss of traditions and systematic destruction of evidence of the past, such as documents, monuments, vernacular architecture, and sacred art, was beginning. If until the 1940s Italians rarely considered themselves Brazilians, and everything that referred to their rural roots and the old distant homeland was a source of pride, it was now necessary to create a new identity, one that would be fully integrated into "Brazilianness". This "official" Brazilianness prescribed for the colonial region being Lusophone, urban, bourgeois, and adept at innovation, as long as morality remained unshaken.[1][2][4]

The practical reflex of the modernizing program was the intense growth of the industrial sector, with the development of a pole concentrated in Caxias do Sul, a city that, due to a privileged location, placed itself since the 19th century at the forefront of most of the advances. Today, the former Italian colonial region is densely populated and one of the richest, most dynamic and populous in the state. However, this accentuated and accelerated growth has not occurred without issues such as urban violence, inequality and exclusion of the poor, environmental devastation, inefficient policies, economic and real estate speculation, the lack of popular housing, sanitation, and the precariousness of basic services.[6][3]

Predecessors

The presence of Italians in the area today, defined by the limits of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, is attested at least since the 17th century when several Jesuit missionaries of such nationality went to the region to catechize the natives and organize reductions. But they were often ephemeral presences, itinerating through different American regions. Their presence remained extremely reduced until the beginning of the 19th century, when the population of newcomers began to increase, settling mainly in the capital Porto Alegre, but also reaching several other cities, such as Livramento, Bagé, and Pelotas. They were mainly engaged in commerce, but journalists, politicians, artists, teachers, industrialists, and other professionals also arrived. Many of these founded families which are still flourishing.[1]

In this period Italian immigration was still spontaneous, as the official interests were focused elsewhere. Soon after the transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil in 1808, the government began to encourage the immigration of German and Swiss settlers to Rio de Janeiro. In 1824, Germans became the preferred population in a program to create colonies in Rio Grande do Sul. The project was revolutionary: At a time when a system of large-scale monocultures for export or extensive cattle raising still prevailed, with a slave labor force, the goal was to create a stable rural population of free men who owned small plots of land, settled on unclaimed land, which could improve the usually precarious internal supply of basic consumer products, and help "whiten" the Brazilian population, at the time largely made up of black and indigenous people. In addition, this population would constitute a military reserve force for use in eventual border conflicts.[1][2]

The first stage of German colonization was considered a success, and there was a desire to repeat the mobilization. However, the social, political, and economic context of the nation changed and frustrated the plans. The Germans began to experience difficulties as early as 1830 when funding for the settlers was cut, and the plots allocated to them were reduced in size and no longer free of charge. With the prohibition of the slave trade in 1850, the slave system faced a labor crisis, and several government attempts to create mechanisms that favored the hiring of free employees achieved little or no results, mainly due to the abusive demands that the landowners included in the contracts, whose terms in many cases differed little from a regime of slavery. Several revolts and protests of settlers were registered due to mistreatment and poor working and living conditions. This news reached Europe, causing a wave of indignation. The result was that the Germans and Swiss could no longer easily be persuaded to immigrate, and by mid-century only about 30,000 new immigrants arrived.[1][3]

The Immigration Wave

In 1867, in face of the poor results of the colonizing program, the government legislated again, restoring some of the initial advantages and creating others. Now the rural lot could be paid off in ten years, with a two-year grace period; travel within the country to the final destination would be paid for by the government; the settler would receive help for the construction of his first house and for their first crops, with seeds, basic equipment, and some materials, as well as a cash. Medical and religious care was also planned. The government desired to attract up to 350,000 German, Swiss, and English settlers, but this did not happen. By 1875 only 19,000 new settlers arrived in the state.[1]

At this time Italy was going through a crisis, and a consideralbe part of the population, very poor and ravaged by famine, epidemics, as well as a long series of wars, was beginning its flight to the American continent. They came mostly from the countryside, where their families had generally never been property owners having a long history of servitude. They ended up piled up in the cities in generally subhuman conditions and even those who were mostly property owners had been impoverished by steeply rising taxes and competition with the large landowners, getting into debt and needing to sell their land. Those who were still in the countryside had their harsh condition hardened. The depression did not only affect Italy, but many other European countries. According to Zuleika Alvin, "for some expelling countries, such as Italy and Spain, for example, the descriptions of the places where immigrants lived and the promiscuity in which they were forced to live due to poverty are good examples of the repercussion of the economic crisis on the bucolic landscape of the countryside".[3] The researcher continues:

As it was being implemented, this process was releasing a surplus of labor that the late industrialization of countries like Italy and Germany, for example, was unable to absorb. This, coupled with a population growth never seen before, such as that which occurred in the nineteenth century, when the population of Europe increased two and a half times, the advance of technology, which allowed tasks previously performed by man to be performed by machines, and the unprecedented improvements in transportation, made available to the market a horde of landless and unemployed peasants[3]

In Europe, between 1830 and 1930, more than 50 million people left their homes in search of the American dream.[3] Texts from diplomats and politicians of the time show that the Italian population was lost within the newly unified and still unstable nation, "they were not citizens to help and defend, but impertinent peasants who with their misery and ignorance offend the Fatherland,"[3] so that protectionist measures were few, hesitant, late and had little effect. The role of the Italian authorities consisted of advising the emigrants, acting most vigorously in a few problematic individual cases, and leaving in practice all recruitment, transfer and settlement to the international shipowners and Brazilian imperial agents.[1][2][3]

Most of those who went to Brazil were not only looking for the chance to prosper but were mainly driven by the idea of becoming landowners.[1][2] Legends about fantastic creatures and immeasurable riches were taken as fact by the simplest people, who became the target of recruiting agents, who fed the old stories about Cocanha, a land of fabulous wealth, located it in Brazil, where there would be an easy fortune, where they would realize their dream of being free, rich, and, finally, also masters.[7][8]

However, most of the Italians never materialized their wishes, having been directed to the coffee plantations of São Paulo, finding poor survival conditions, and without having, for the most part, their own land, which reproduced the same situation from which they had wanted to flee.[1][2][3] Reports from the time bear witness to the discouragement and despair of the newcomers to the coffee plantations, deprived of their own initiative, immobilized by the terms of contracts, unable to rebuild the landscape in a way that resembled their homeland, cooped up in small houses of wattle and daub lent by the bosses, and constrained to a submission that had to be expressed with gratitude, for the "kindness of the bosses in getting them out of their misery and giving them work". Many rebelled against such conditions of exploitation and oppression or abandoned the countryside seeking the cities and swelling the marginalized mass.[3]

In Rio Grande do Sul, the original idea of creating productive small farms for free men was maintained. After creating four new German colonies, in 1869, the provincial government requested from the Empire the concession of more vacant lands for another two. The following year, 32 square leagues were granted in the northeast of the province, where the colonies Conde d'Eu (currently the city of Garibaldi) and Dona Isabel (currently Bento Gonçalves) were founded. It was intended to introduce 40,000 German settlers in ten years, but fewer than 4,000 candidates were enrolled, a large part was not German, but Portuguese and the project went into recess.[1][2]

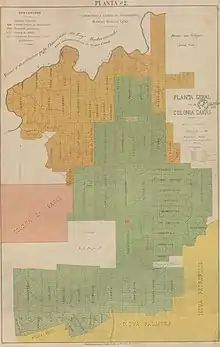

Around 1874, the Italians in São Paulo were already exceeding the capacity of the coffee plantations. Thus, in 1875 the imperial government took over the Conde d'Eu and Dona Isabel colonies to accommodate this population without a certain destination, and soon the first families were settled. In the same year a new area was delimited, the Colônia Fundos de Nova Palmira, renamed in 1877 as Colônia Caxias (origin of Caxias do Sul, São Marcos, Flores da Cunha, Nova Pádua and Farroupilha), year in which the Fourth Colony (currently Silveira Martins) was created. These four colonies formed the main nuclei of Italian colonization in the state.[1]

The Italian colonial zone was originally covered by virgin forest, with a few sparse stretches of field. Several indigenous tribes still lived there, which had been eradicated or expelled to make it possible for the colonists to settle there. They embarked after days or weeks of waiting at the quays of Genoa, from where most left, or Havre in France. Usually badly housed; many slept in the streets and were systematically robbed, cheated, and extorted by swindlers and corrupt officials. However, the accounts are not always the same, and for several groups, the boarding was quick and uncomplicated.[3]

The sea voyage lasted a month or more, made on overcrowded ships, where conditions were poor. The immigrants were also poorly clothed, and faced precarious hygiene, although most accounts state they were given much better and more abundant food than they had access to in their former homes. They arrived at the ports of Rio de Janeiro or Santos, where they were temporarily placed in a pavilion awaiting referral. If diseases were suspected, which was common, they were quarantined.[3] If they did not go to São Paulo, they went south in smaller ships, until they reached the capital Porto Alegre, where they unloaded and waited to be transferred to another pavilion. From Porto Alegre, by boat, they would follow the Caí river to São Sebastião do Caí, an important commercial warehouse and a support center for travelers. From there the trip would be made in caravans, usually on foot or on the backs of donkeys, led by experienced guides, up the rugged mountains of the Northeast, to another reception pavilion located in the 1st Legua of the Caxias Colony, in the place today called Nova Milano, from where they would be distributed to the other colonies demarcated by the government. There was a high mortality rate on the trips and in this period of moving and first settlement, especially among children and the elderly.[9][10]

Despite several difficulties, the initiative was successful, leading to the formation of new settlement centers.[11] Official statistics point to the entry of more than one and a half million Italians throughout Brazil between 1819 and 1940.[3] It is estimated that 76,168 of them settled in Rio Grande do Sul between 1824 and 1914, and that up to 100,000 Italians entered the state in this period, about 10% of them spontaneously emigrating in good economic conditions, or displaced from groups previously settled in Uruguay and Argentina. The majority came from northern Italy (Veneto, Lombardy, Tyrol, Friuli), and about 75% were farmers. In 1914, the government formalized the closure of the state-subsidized colonizing program, but many would still come. In the 1920s, several waves of settlers in Rio Grande do Sul began to move to the states of Santa Catarina and Paraná.[1]

The rural colonies and communities

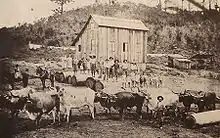

Few were the peasant owners in 19th century Italy, with medieval traditions, where land ownership meant power, prestige, wealth, and nobility. There are many accounts from the first settlers about the hardships and isolation they experienced in the early days. Everything was still to be done, and the nature of the region was rough, with a rugged terrain and a largely stony soil. A thick forest of thorny araucaria trees covered the landscape, the roads were simple trails opened in the forest that became impassable on rainy days, the promised official help was not as consistent as desired, and the first years in the colony invariably meant constant exhausting work from which not even the children were spared, such was the pressure to survive. As slave labor was forbidden in the colony, all activities were carried out by the family.[1][9]

However, the land was fertile, with good water and a mild climate. Soon the surpluses started to be traded, reaching as far as Porto Alegre, fulfilling the government's objectives to increase domestic supply, and generating an income for the settlers that could be reinvested, providing the first comforts, such as a bigger house and better equipment, besides favoring the birth of the first handcraft manufactures and small industries that processed the rural production. Moreover, the experience of the effective possession of their plots, even if of only a few hectares, would prove to define an entire culture to be created in the New World, where a narrative of success and self-glorification of long and wide influence would be established.[9][1] In the words of De Boni & Costa,

"The governmental abandonment of the early days, with all its negative aspects, was, however, one of the reasons for the maintenance of the Italian identity and served to place the immigrant in front of a dilemma: either he fought with all his strength to survive, or he would be carried away by the harshness of life in those early days. Challenged, he reworked a world of values, in which property, thrift, and work occupied dominant places. [...] The homeland had been left because it lacked the perspective of being able to become an owner, as the propaganda said it was possible to become in Brazil, and as, in fact, was happening in Rio Grande do Sul. [...] But the land is nothing without work. The adventures of the trip and the acquisition of the land would have been of little use if it was not plowed. And this required the effort of those who acquired it."[1]

The colonies were divided into long lots with a narrow frontage facing a trail, which allowed the movement of people and cargo between the properties, forming a dense road network. This network extended throughout the territory of the colonies and interconnected them, although its practical implementation was only completed after many years when the distribution of land and the settlement of the new arrivals was completed. Although there were no insurmountable barriers in the rugged geography of the colonies, and many trails were opened in all directions, for a long time between the main headquarters there were only a few viable paths for passing caravans of cargo or people.[10]

The organization of the farm was simple and practical. A rustic wooden house, sometimes of adobe or stone, divided into a large kitchen where the focolaro (the domestic fire) was, and one more living room, one or two bedrooms, and an attic as storage or additional sleeping quarters. There was usually a basement for a domestic canteen and storage room. Next to the house, there would be a stable, a barn, a pigsty, and a chicken coop. Often the kitchen was located in a separate room from the main body, because of the danger of fire, as it kept burning all day. A vegetable garden was also planted, in addition to the main crops.[13] In the second stage, when the situation stabilized, the rustic houses and pavilions of the beginning were replaced by larger and better-equipped facilities, often with external and internal ornaments, of which an important group of stone, masonry, and wood, in various typologies survives.[3][12]

Life in the countryside gave rise to the formation of its folklore in rural communities, which transformed the traditional heritage they brought from Europe, adapting it to a new setting and a new context. Formerly gathered in community villages, in Rio Grande do Sul they lived scattered and isolated in family units on each lot, in houses that differed from those they knew both in form and uses and materials. From this developed a whole tradition of vernacular architecture today esteemed for its originality and beauty. Clothing was also adapted to new ways of working and a different climate, the cuisine absorbed native plants and animals and indigenous and local dishes, and the language received influence from Portuguese and various Italian dialects, forming a new dialect, Talian, in general use in the colonies.[1][3]

The man was the leader of the family and distributed the functions of each member. He, the "boss-father," and his older sons were responsible for the heavier work of carpentry, blacksmithing, clearing the woods, and opening crops, which, along with the vegetable gardens and animal husbandry, were later left mainly to the woman and her daughters and sons, who were used to the hard work from a young age. As their survival depended only on them, families tended to be numerous to create more arms for work.[14]

This hierarchical and patriarchal system of family production would be continued into the 20th century when survival in the face of a wilderness was no longer an urgent threat. The woman had a subordinate role, which, although little recognized, was essential as a partner in work and as the family's unifying center. She was also necessary for the elementary education of the offspring and for early religious instruction, and had important socializing functions. She was the mediator figure, calming conflicts, facilitating solidarity between generations, and contact between the various groups of settlers. It was also due to the women, especially the grandmothers, the preservation of the family's oral memory, the transmission of traditions, customs, legends, and stories of ancestors' experiences. The patriarchal model was repeated in the urban area as it grew, with its diverse trades and demands.[15]

Coming from different Italian regions, many groups barely understood each other, and the political and ideological conflicts they had brought from Europe, especially of the liberals, republicans, and freemasons against the Catholics, monarchists, and traditionalists, continued to exert influence in Brazil, having as a result waves of protests and violent conflicts in several communities. On the other hand, this served as a powerful unifying link between the divergent groups.[1][17][18]

In rural life, in particular, religion exerted a central influence on customs and the organization of daily life, and one of the main complaints in the early days was the scarcity of priests, forcing many lay people to take on liturgical functions. The feasts of the chapel's patron saint, Christmas, New Year's Eve, Easter, and other holy days, were used to gather the entire community. The chapels in many cases gave rise to the formation of new urban centers around them. Generally linked to the administration of the chapels and supported by the public authorities, the first community leaders emerged, in charge of resolving conflicts, organizing collective actions, forwarding complaints to the authorities, and assisting the priests when they visited since the chapels had no resident priest.[1][18][19][20] It was also religion that gave rise to the first artistic expressions within such communities.[21]

By the beginning of the 20th century, the colonial area had established a thriving economic activity, becoming one of the main producing centers in the state. Although very diversified, production was led by the wineries, which by this time were collectively the largest wine producer in Brazil, having won many national and international awards. But the wine industry was in a chronic crisis and profits were oscillating. At this time a large-scale cooperative experiment was made under the aegis of the Italian technician Giuseppe Paternó, invited by the state government, to improve the quality of the product and make it more competitive, fight fakes and middlemen, diversify production with fine grape varieties and intensify the exchange of experiences among producers, but it ultimately failed.[22][23][24]

Most Italians would remain in the countryside for at least two generations, benefiting from the technological and scientific advances that significantly improved their living conditions and facilitated rural production, such as the improvement of medicine and hygiene, and the introduction of electricity and mechanization in farming. They grew a variety of grains, vegetables, and fruit trees, but maize (for polenta), wheat (for bread), and grapes (for wine) predominated.[1][3]

Despite the significant success of rural production, over the years other problems began to surface. The Italians commonly transferred all the land to one of the sons, usually the youngest, who was left to take care of the parents in their old age. At times the plots were divided among siblings, but their small size soon posed an impediment to successive divisions. The disinherited had to leave in search of other placements, starting a population exodus to new colonies that were emerging or to other states.[1][25][26]

The destabilization of the rural way of life was accentuated in the interwar period, when the Italian culture was repressed by Getúlio Vargas' nationalist program, and the regional production system began to concentrate on industry and commerce. Investments flowed mainly to the rapidly growing cities, increasing the problems in the countryside, whose products - including handicrafts - suffered increasing competition from imported and industrialized goods and became dependent on middlemen for their sales. A good part of those landless children without a defined future ended up taking refuge in the cities and became part of the labor and commercial proletariat.[1][25][26]

The colonial cities

The government foresaw the evolution of the rural colonies into cities, and in the blueprints of the projects an area was delimited for the formation of an urban headquarter, which should concentrate the colonial administration, commerce, and services such as medical and religious services, with plots typical of cities, much smaller than the rural plots. As the immigrants were free to choose their lots, those who were not farmers generally preferred to remain in these centers, where they could develop their trades. There was also provision for the formation of several other small urbanized centers dotting the rural landscape, which would function as centers of support, meeting, and exchange for populations farther from the main headquarters.[1][20]

The layout of the headquarters followed the model of the orthogonal Roman grid, disregarding the topography of the land, which would later give rise to urbanization problems. Some very quickly grew into dynamic and well-organized villages, with schools, churches, and other public buildings, such as Bento Gonçalves (former Dona Isabel Colony), Garibaldi (former Count of Eu), and Silveira Martins (former Fourth Colony).[11][27] However, Bento Gonçalves had its development hindered until 1917 when it was connected to the state railroads,[10] and Antônio Prado, which was envisioned by the government to become the head of the region, ended up stagnating due to the detour of a fundamental road for the interconnection between that area and northern Brazil. It passed through Caxias do Sul, allowing the almost intact preservation of its historical center.[28] This city, thus, assumed a clear regional protagonism from the beginning.[10]

For Santos & Zanini, "similarities can be found between the colonization of Caxias do Sul and cities of German colonization, even from other states, such as, for example, that of Blumenau, in Santa Catarina, where, analogously to Caxias do Sul, a strong commercial and industrial bourgeoisie linked to colonization was established, which encouraged the maintenance of a distinctiveness based on ethnicity, "where "Italianness" is observed as a sense of belonging based on an origin that historically dialogued with various periods of regional and national life."[27]

With the collaboration of a class of public servants, this elite, which included some large fortunes, as was the case of Abramo Eberle, promoted a rich intellectual and cultural flourishing of the erudite profile, which besides expressing the evolution of aesthetic customs and ideologies, was also evidence of material success and a form of social affirmation.[1][29]

In the first decades of the 20th century, in the main colonial cities, there were newspapers, movie theaters, theaters, orchestras, theatrical and lyrical groups, literary soirées, beneficent kermesses, and collective actions to help the poor and the Church. The large masonry mansions multiplied, and the wooden ones were enlarged and ornamented with wainscoting and other artistic details, replacing the primitive urban landscape composed of small and rustic dwellings. The colonial matrices were also replaced by more solid and imposing buildings, sometimes decorated with refinement. Socialization was intensified by the foundation of a series of mutual aid associations, trade associations, lay religious circles, political party directories, and above all by the creation of social, sports, cultural and recreational clubs. In these places ideas, philosophies, and ways of life were debated, being important disseminating centers of cultural, ideological, and social trends.[1][29]

From consolidation to contemporaneity

In the 1920s, the great contribution of the Italian cities and colonies to the development of Rio Grande do Sul was evident. Statistics gathered in this decade pointed to accelerated economic growth: While the seven main colonies made up only 2.4% of the territory and accounted for only 7.9% of the total population, they were responsible for about 60% of the total grain production, 30% of wheat production, 25% of beans, potatoes, and tobacco; they raised the largest pig herd in Brazil, and maintained about 40% of the state's industries.[30][31] Other indicators showed a birth rate two to three times the state average, the lowest mortality rates, and almost non-existent crime.[31]

At the same time, immigration was responsible for a significant change in the ethnic profile of the state. If in the 1872 census, there were 59.4% whites, 18.3% blacks, and 16.4% mestizos, in 1890 there were 70.17% whites, 8.68% blacks, and 15.80% mestizos.[31] This progress caught the attention of the state authorities as well as the Italian authorities, who after a period of denying their responsibility for the population flight, were now eager to re-establish contact with the expatriate.[2]

Since the end of the XIX century, several local and regional fairs had been organized, where the most typical products of each area were exposed to stimulate commerce and exchange of experiences among the producers. The most notable of these fairs is the Festa da Uva, which in the 1930s was defined in the model in which it is known today. The feast celebrated grapes and wine, at the time the main products of the colonial economy, and romanticized them as a gift from the gods, worked by the virtue of the Italian through millenary traditions. This ideology was an important element in the formation of a rich and influential discourse glorifying the achievements of the Italians, a discourse that was already clearly outlined in the numerous and substantial essays and articles contained in an album commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of immigration in 1925, an event celebrated with grand festivities in the capital and several colonial towns, with the sponsorship of the high business community, the state and Italian governments, and with the blessings of the Pope. The rhetoric was influenced by fascism and theories of racial supremacy based on land, ethnicity, labor, morality, and religion, decanting the immigrant from his humble rural origins to a civilizing agent.[5][1][27][32][33][4]

The 1930s were difficult for the peasants and the proletarianized urban workers, but still, they participated in the apotheosis. They joined the parades of floats of the Festa da Uva, with their tools and work clothes under the frenzied applause of the visiting crowd. The feast became a tourist success in the state in a few years, understood as the main stage for ideological, identity and community representations of "Italianness", receiving collaborators and exhibitors from all over the colonial region and the approval of distinguished Portuguese-Brazilian intellectuals and politicians.[32][34]

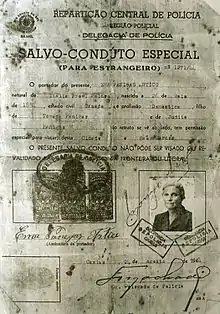

With the hardening of the Getúlio Vargas regime toward the cultural and ethnic homogenization of the Brazilian population, the context changed. In the name of eradicating the undesirable "racial cysts that imprudently formed in Rio Grande do Sul, São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, Mato Grosso, and Pará," the Italian culture was repressed, and with Brazil's entry into World War II against Germany and Italy, people's movements were controlled, the use of Talian in public was forbidden, and several cases of violence and arrests of Italians were recorded.[35][36] As Ribeiro stated:[36]

"The regional community was severely tested. The settlers, by being forbidden to speak in public places, were also deprived of leaving their homes, selling their products and buying others, holding and attending parties, of singing. This amounts to a confiscation of the exercise of communal life and sociability."

The repercussions of this large-scale censorship were profound and long-lasting, although the government from the 1950s on sought to rescue the Italian contribution to the nation's growth in a general modernization campaign. Partly because of repression, many traditions disappeared, the use of the language declined sharply, and the concern with preserving the testimonies of the past dissolved. In this process of forced "Brazilianment", significant parts of the oral memory, of the traditional techniques and uses, and the artistic heritage were lost.[37][38][39][40][41]

In 1975, celebrating the centennial of immigration, festivities, and exhibitions were promoted by the government and the colonial municipalities, with the support of the Italian government. A new commemorative album was published reiterating the importance of the Italians for the growth of the state, and a series of parallel activities were organized, such as lectures and conferences, musical performances, theater plays, film festivals, economic missions, and art exhibitions. This movement stimulated the awakening of academic interest in the subject of Italian immigration and colonization in the state and gave rise to the foundation of museums and archives, Italian cultural associations, the construction of monuments, and other memory rescue activities.[6][42]

Porto Alegre and other cities

The Italians were not only present in the typical colonial regions. Hundreds of Italians circulated the state since the early nineteenth century, concentrated in Porto Alegre, performing a multiplicity of urban trades, with many prominent figures.[43][44]

When the fiftieth anniversary of immigration was celebrated in 1925, the state government organized an exhibition in Porto Alegre, bringing the best agro-industrial and artistic products from the colonies, being a success, and at the same time published a substantial collection of critical essays and informative and statistical articles about the Italian presence in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in two volumes, entitled Cinquantenario della Colonizzazione Italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud, 1875-1925. In it was done a mapping, unprecedented for its comprehensiveness and detail, of the activity of the Italians and their descendants in a long list of cities where they left their marks in the most diverse domains.[1] Also not forgotten was the passing but powerful presence of other Italians such as Tito Livio Zambeccari and Giuseppe Garibaldi.[45]

Legacy

The legend of the immigrant and his descendants, since the 1970s, has generated a vast literature, which continues to grow, and has led to the formation of several research groups in universities, exclusively focused on the study of this theme in its various expressions and developments,[46] and has also given rise to a large number of popular literary productions, plastic/visual, poetic, theatrical, television, and film creations, of a documentary, humorous, fictional, or artistic nature.[47]

The patriotic ideology cultivated since the beginning of the 20th century, despite having encountered setbacks in its trajectory, is still present in popular culture and official propaganda, perpetuating myths and stereotypes.[48][27][49] However, given the complexity and contradictions of the colonies' evolution process, since the 1970s this discourse has been revised and criticized by academics, who have emphasized the intentional aspects of the historical attempts to affirm the elites and the ambiguous and partly artificial features of the process of building sociocultural identities, also showing that several other cultures and ethnicities have actively participated in the growth of the region, especially large groups of newcomers that in some places, in recent decades, have been supplanting the population of Italian origin, bringing other pasts, other cultural bases, other needs, and demanding space and recognition.[5][49][50][51][52]

Still, it is a consensus that Italians left an important legacy on multiple spheres; in crafts, architecture, economy, politics, festivals, folklore and legends, cuisine, sports and games, scholarly arts, language, science, ways of working, understanding the world, living and relating, and acting in groups.[53][54][55][56][57][58] The Talian dialect was declared a cultural heritage of the state,[59] and in 2014 was recognized by the National Institute of Historical and Artistic Heritage (IPHAN) as a Brazilian Cultural Reference, being included in the National Inventory of Linguistic Diversity.[60]

The São Romédio Chapel in Caxias do Sul, located in the place where the first organized community of Italians was formed,[61][62] the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Caravaggio in Farroupilha,[63] and the historical itinerary Caminhos de Pedra in Bento Gonçalves have also been declared by the government as a Historical and Cultural Heritage of Rio Grande do Sul.[64]

In Nova Milano, where the immigrants' main reception headquarter used to be, the Italian Immigration Park was created in 1975. At the site, there is a monument to the immigrants, created by Carlos Tenius, a replica of the Lion of St. Mark, a symbol of Venice, offered by the Italian government, plaques representing the Italian regions, and the Museum of Italian Immigration and of Grape and Wine.[65][66] Several other monuments are spread around the state marking and honoring the Italian presence, highlighting the National Monument to the Immigrant in Caxias do Sul, inaugurated in 1954. The Day of the Italian Ethnicity in Rio Grande does Sul is celebrated on May 20.[67]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Costa, Rovílio; De Boni, Luís Alberto (2000). "Os Italianos no Rio Grande do Sul". Cinquantenario della Colonizzazione Italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud, 1875-1925. Vol. 1. Posenato Arte & Cultura. pp. 1–22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Iotti, Luiza Horn (1999). Dal Bó, Juventino; Iotti, Luiza Horn; Machado, Maria Beatriz Pinheiro (eds.). "Imigração Italiana e Estudos Ítalo-Brasileiros — Anais do Simpósio Internacional sobre Imigração Italiana e IX Fórum de Estudos Ítalo-Brasileiros". EDUCS: 173–189.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Alvin, Zuleika (2010). "Imigrantes: a vida privada dos pobres do campo". In Novais, Fernando A. (ed.). História da Vida Privada no Brasil. Vol. 3, República: da Belle Époque à Era do Rádio (in Portuguese). Vol. 3. Companhia das Letras. pp. 215–287.

- 1 2 Giron, Loraine Slomp (1994). As Sombras do Littorio: o fascismo no Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). Parlenda.

- 1 2 3 Miriam de Oliveira, Santos; Zanini, Maria Catarina C (2013). "As Festas da Uva de Caxias do Sul, RS (Brasil) : Historicidade, mensagens, memórias e significados". Artelogie.

- 1 2 Lima, Tatiane de (2016). "A história da imigração italiana no Rio Grande do Sul em álbuns comemorativos". História Unicap. 3 (6): 272–279. doi:10.25247/hu.2016.v3n6.p272-279. S2CID 165107524.

- ↑ Gomes, Mariani Vanessa; Damke, Ciro (2017). "O Paese di Cuccagna e a Phantasieinsel: a construção do imaginário popular dos imigrantes alemães e italianos" (PDF). XIII Seminário nacional de Literatura, História e Memória e IV Congresso Internacional de Pesquisas em Letras no Contexto Latino Americano.

- ↑ Pozenato, José Clemente (2000). A Cocanha. Mercado Aberto. p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Maestri, Mário (1999). "A travessia e a mata: memória e história". In Dal Bó, Juventino; Iotti, Luiza Horn; Machado, Maria Beatriz Pinheiro (eds.). Imigração Italiana e Estudos Ítalo-Brasileiros — Anais do Simpósio Internacional sobre Imigração Italiana e IX Fórum de Estudos Ítalo-Brasileiros (in Portuguese). EDUCS. pp. 190–207.

- 1 2 3 4 Pedro de Alcântara Bittencourt, César (2012). "A formação de roteiro turístico-cultural e a estrutura urbana regional: estudo da Serra Gaúcha (RS)" (PDF). VII Seminário em Turismo do MERCOSUL.

- 1 2 Todt, Viviane; Thum, Adriane Brill; Pessin, Alexandre (2014). "Diferença entre Projeto e Implantação - Colônia de Alfredo Chaves, 1884". Anais do Congresso Brasileiro de Cartografia.

- 1 2 Posenato, Júlio (2004). "A Arquitetura do Norte da Itália e das Colônias Italianas de Pequena Propriedade no Brasil". In Bellotto, Manoel Lelo; Martins, Neide Marcondes (eds.). Turbulência cultural em cenários de transição: o século XIX ibero-americano (in Portuguese). EdUSP. pp. 51–75.

- ↑ Filippon, Maria Isabel (2007). Dissertação de Mestrado. "A Casa do Imigrante Italiano: A Linguagem do Espaço de Habitar". UCS: 125.

- ↑ Herédia, Vania Beatriz Merlotti; Giron, Loraine Slomp (2006). "Identidade, Trabalho e Turismo". IV SeminTUR – Seminário de Pesquisa em Turismo do MERCOSUL.

- ↑ Santos, Miriam de Oliveira (2007). "O papel da mulher na reprodução social da família, um estudo de caso com descendentes de imigrantes europeus". Ártemis (7): 88–92. doi:10.15668/1807-8214/artemis.v7p88-92.

- ↑ Bertussi, Paulo Iroquez (1987). "Elementos de Arquitetura da Imigração Italiana". In Weimer, Günter (ed.). A Arquitetura no Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). Mercado Aberto. pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Seyferth, Giralda (2000). "As identidades dos imigrantes e o melting pot nacional". Horizontes Antropológicos. 16 (14): 143–176. doi:10.1590/S0104-71832000001400007.

- 1 2 Valduga, Gustavo (2008). Paz, Itália, Jesus: uma identidade para imigrantes italianos e seus descendentes: o papel do jornal Correio Riograndense (1930-1945) (in Portuguese). EDIPUCRS. pp. 106–118.

- ↑ Corrêa, Marcelo Armellini (June 2015). "Antes católicos, depois austríacos e enfim italianos: a identidade católica dos imigrantes trentinos". XXVIII Simpósio Nacional de História.

- 1 2 Zanini, Maria Catarina Chitolina.; Vendrame, Maíra Ines (2014). "Imigrantes italianos no Brasil meridional: práticas sociais e culturais na conformação das comunidades coloniais". Estudos Ibero-Americanos. 40 (1): 128–149. doi:10.15448/1980-864X.2014.1.17268.

- ↑ Ribeiro, Cleodes M. P. J. O lugar do canto (in Portuguese). UCS.

- ↑ Santos, Sandro Rogério dos (2014). "Stefano Paternó e a Construção do Empreendedorismo Cooperativo na Serra Gaúcha". In Ruggiero, Antonio de; Fay, Claudia Musa (eds.). Imigrantes Empreendedores na História do Brasil: estudos de caso (in Portuguese). EdiPUCRS. pp. 141–155.

- ↑ Picolotto, Everton Lazzaretti (2011). Tese de Doutorado. "As Mãos que Alimentam a Nação: agricultura familiar, sindicalismo e política". UFRRJ: 55–65.

- ↑ Santos, Sandro Rogério dos (2011). Tese de Doutorado. "A Construção do Cooperativismo em Caxias do Sul: cooperativa vitivinícola Aliança (1931-2011)". PUCRS: 41–97.

- 1 2 Herédia, Vania Beatriz Merlotti; Machado, Maria Abel (2001). "Associação dos Comerciantes: Uma Forma de Organização dos Imigrantes Europeus nas Colônias Agrícolas no Sul do Brasil". Scripta Nova — Revista Electrónica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales. 94 (28).

- 1 2 Herédia, Vânia Beatriz Merlotti (1997). Processo de Industrialização da Zona Colonial Italiana (in Portuguese). EDUCS. pp. 166–167.

- 1 2 3 4 Zanini, Maria Catarina Chitolina; Santos, Miriam de Oliveira (2009). "Especificidades da Identidade de descendentes de italianos no sul do Brasil: breve análise das regiões de Caxias do Sul e Santa Maria". Antropolítica (27).

- ↑ Memória e Preservação: Antônio Prado - RS (in Portuguese). Iphan / Programa Monumenta. 2009. p. 7.

- 1 2 Machado, Maria Abel (2001). Construindo uma Cidade: História de Caxias do Sul - 1875-1950 (in Portuguese). Maneco. pp. 50–62.

- ↑ Gobbato, Celeste (2000). "Il colono italiano ed il suo contributo nello sviluppo dell'industria riograndense". In Cichero, Lorenzo (ed.). Cinquantenario della Colonizzazione Italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud, 1875-1925. Vol. 1. Posenato Arte & Cultura. pp. 195–242.

- 1 2 3 Truda, Francisco de Leonardo (2000). "L'influenza etnica, sociale ed economica della colonizzazione italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud". In Cichero, Lorenzo (ed.). Cinquantenario della Colonizzazione Italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud, 1875-1925. Vol. 1. Posenato Arte & Cultura. pp. 246–254.

- 1 2 Ribeiro 2002, pp. 91–110.

- ↑ Santos, Miriam de Oliveira (2015). Bendito é o Fruto: Festa da Uva e identidade entre os descendentes de imigrantes italianos (in Portuguese). Léo Christiano Editorial. pp. 69–73.

- ↑ "Comemorações do Dia da "Etnia Italiana": abertura da exposição Terra Mater". 10 May 2019.

- ↑ Ribeiro (2002, pp. 137–147)

- 1 2 Maestri, Mário (2014). "A Lei do Silêncio: história e mitos da imigração ítalo-gaúcha". Revista Vox (7).

- ↑ Museu Municipal de Caxias do Sul. (1993). "A cidade ficou igual a tantas outras... As diferenças?". Boletim Memória (16).

- ↑ Caon, Marcelo (2010). Dissertação de Mestrado. "Memória e Cidade: o processo de preservação do patrimônio histórico edificado em Caxias do Sul 1974-1994". PUCRS.

- ↑ Ribeiro, M. P. J. Cleodes. O lugar do canto. UCS.

- ↑ Ribeiro (2002, pp. 147–191)

- ↑ Adami, João Spadari (1966). Festas da Uva 1881-1965 (in Portuguese). São Miguel. pp. 85–178.

- ↑ Kemmerich, Ricardo; Cruz, Jorge Alberto Soares (2019). "A quarta colônia e a manutenção da identidade, memoria e cultura regional". Estudios Históricos. 11 (22).

- ↑ Cichero, Lorenzo, ed. (2000). "Municipio di Porto Alegre: dati generali". Cinquantenario della Colonizzazione Italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud, 1875-1925 (in Portuguese). Vol. 2. Posenato Arte & Cultura. pp. 337–398.

- ↑ Damasceno, Athos (1971). Artes Plásticas no Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). Globo. pp. 128–131, 260–269, 389–418.

- ↑ Cichero, Lorenzo, ed. (2000). Cinquantenario della Colonizzazione Italiana nel Rio Grande del Sud, 1875-1925. Vol. 1, 2. Posenato Arte & Cultura.

- ↑ Beneduzi, Luís Fernando (2004). Doutorado. "Mal di Paese: as reelaborações de um vêneto imaginário na ex-colônia de Conde D'eu (1884-1925)". UFRGS: 37–44. hdl:10183/14417.

- ↑ Zanini, Maria Catarina C.; Santos, Mirian de O. (2010). "As memórias da Imigração no Rio Grande do Sul". Mneme. 11 (27).

- ↑ Menegotto, Kenia Maria; Espeiorin, Vagner Adilio (September 2010). "Identidade e Retórica em Tempo de Festa da Uva: A Memória Recontada pela Imprensa Regional". XXXIII Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação.

- 1 2 Puhl, Paula Regina; Donato, Aline Streck (2013). "Uva, Cor, Ação! A Cobertura da Festa da Uva pela RBS TV de Caxias do Sul". Revista Brasileira de História da Mídia. 2 (2): 191–197.

- ↑ Seyferth, Giralda (2015). "Prefácio". In Santos, Miriam de Oliveira (ed.). Bendito é o Fruto: Festa da Uva e identidade entre os descendentes de imigrantes italianos (in Portuguese). Léo Christiano Editorial.

- ↑ Santos, Miriam de Oliveira, ed. (2005). Bendito é o Fruto: Festa da Uva e identidade entre os descendentes de imigrantes italianos (in Portuguese). Léo Christiano Editorial. pp. 67–103.

- ↑ Branchi, Ana Lia Dal Pont (2015). Mestrado. "A etnização em Caxias do Sul: a construção da narrativa da "diversidade" no desfile da Festa Nacional da Uva de 2014". UCS: 154–157.

- ↑ Gaspary, Fernanda Peron; Venturini, Ana Paula (2015). "O legado arquitônico da imigração italiana no Rio Grande do Sul: o Moinho Moro". Disciplinarum Scientia — Artes, Letras e Comunicação. 16 (1).

- ↑ Souza, Raquel Eleonora (2016). "O legado estético da colonização italiana no sul do Brasil". Revista Icônica. 2 (1).

- ↑ Colbari, Antonia (1990). "Familismo e Ética do Trabalho: O Legado dos Imigrantes Italianos para a Cultura Brasileira". Revista Brasileira de História. 17 (34): 53–74. doi:10.1590/S0102-01881997000200003.

- ↑ "Última reportagem especial mostra o legado deixado pela imigração na Serra". Rádio Caxias (in Portuguese). 22 May 2015.

- ↑ Burgos, Mirtia Suzana (2005). "Jogos tradicionais e legado histórico dos descendentes italianos em Caxias do Sul, Relvado e Santa Maria - RS". In Mazo, Janice Zarpellon; Reppold Filho, Alberto Reinaldo (eds.). Atlas do Esporte no Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). UFRGS. p. 10.

- ↑ Pierozan, Vinício Luís; Manfio, Vanessa (2019). "Território, cultura e identidade dos colonizadores italianos no Rio Grande do Sul: uma análise da Serra Gaúcha e da Quarta Colônia". Geousp – Espaço e Tempo. 23 (1): 144–162. doi:10.11606/issn.2179-0892.geousp.2019.146130. S2CID 188920235.

- ↑ Tonial, Honório (26 June 2009). "Aprovado projeto que declara o Talian como patrimônio do RS". Instituto de Investigação e Desenvolvimento em Política Linguística (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2012-01-27.

- ↑ "Talian é reconhecido pelo Iphan como referência cultural brasileira". Pioneiro (in Portuguese). 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Assembleia Legislativa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Lei nº 12.440, 30 March 2016.

- ↑ Andrade, Andrei (18 March 2016). "Nos 140 anos de São Romédio, moradores da primeira comunidade de Caxias compartilham memórias". Pioneiro (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Santuário de Nossa Senhora do Caravaggio é transformado em patrimônio do RS". Governo do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (in Portuguese). 26 May 2006.

- ↑ Strassburger, Nandri Cândida; Teixeira, Paulo Roberto; Michelin, Rita L (November 2012). "Roteiro Caminhos de Pedra - Bento Gonçalves - RS: análise do número de visitantes no período de 1997 a 2011". Anais do VII Seminário de Pesquisa em Turismo do Mercosul.

- ↑ Graciliano, Tomaz (25 April 2018). "Iniciam obras do Museu da Imigração em Nova Milano". Prefeitura de Farroupilha (in Portuguese).

- ↑ "Nova Milano, onde começa a história da imigração italiana". SIMREDE (in Portuguese). 13 July 2015.

- ↑ "Comemorações do Dia da "Etnia Italiana": abertura da exposição Terra Mater". Consulado Geral da Itália em Porto Alegre (in Portuguese). 10 May 2019.

Bibliography

- Ribeiro, Cleodes (2002). Festa e Identidade: como se fez a Festa da Uva (in Portuguese). EDUCS. pp. 91–110.