Gulamur Rahman Maizbhandari | |

|---|---|

| Personal | |

| Born | Syed Gulamur Rahman 1865 |

| Died | 1937 (aged 71–72) Maizbhandar, Bengal Presidency, British India |

| Resting place | Shrine of Syed Gulamur Rahman Maizbhandari, Maizbhandar, Bangladesh |

| Religion | Islam |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Hanafi |

| Tariqa | Maizbhandari |

| Known for | 2nd leader of the Maizbhandari Sufi Order |

| Relatives | Syed Sofiul bshar maizvandarSyed Abul Bashr Maizbhandari (Son/Successor) Syed Ahmad Ullah (uncle) Ziaul Haq (grandson) |

| Arabic name | |

| Personal (Ism) | Ghulām ar-Raḥmān غلام الرحمن |

| Patronymic (Nasab) | ibn ʿAbd al-Karīm ibn Muṭīʿ Ullāh ibn Ṭayyab Ullāh ibn ʿAbd al-Qādir ibn Ḥamīd ad-Dīn بن عبد الكريم بن مطيع الله بن طيب الله بن عبد القادر بن حميد الدين |

| Epithet (Laqab) | Bābā Bhandārī بابا بهنداري |

| Toponymic (Nisba) | al-Māʾijbhandārī المائجبهنداري as-Sayyid السيد |

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

|

|

Gulamur Rahman Maizbhandari (Bengali: গোলামুর রহমান মাইজভাণ্ডারী; 1865–1937), also known by his sobriquet Baba Bhandari (Bengali: বাবা ভাণ্ডারী), was a Bengali Sufi preacher who succeeded his uncle, Syed Ahmad Ullah, as the head of the Maizbhandari Sufi Order, the first such Sufi order in Bengal.[1]

Background and ancestry

Gulamur Rahman's father was Abdul Karim Shah, Syed Ahmad Ullah's youngest brother, and his mother was Musharaf Jaan. His paternal ancestors were Syeds and originally migrated from Madinah to Gaur, the erstwhile capital of medieval Bengal, via Baghdad and Delhi. His ancestor, Hamid ad-Din, was the appointed Imam and Qadi of Gaur, but due to a sudden epidemic in the city, Hamid later migrated to Patiya in Chittagong District.[2] Hamid's son, and Syed Abdul Qadir, was made the imam of Azimnagar in modern-day Fatikchhari. He had two sons; Syed Ataullah and Syed Tayyab Ullah. The latter had three sons; Syed Ahmad, Syed Matiullah and Syed Abdul Karim, and the youngest son was the father of Syed Gulamur Rahman Baba Bhandari.

Early life and education

He was born into a Bengali Muslim family in the village of Maizbhandar in Fatikchhari, Chittagong on 14 October 1865. His uncle, who called him "the rose of my garden", entrusted him with the teaching of students, particularly adepts.[3] He spent time wandering alone in the woods as part of his spiritual journey.[1] Around 1914, he entered a state of meditation and stopped speaking except on rare occasions, thus becoming known as a magdub pir. In 1928, he moved out of his father's house into his own, where disciples and his four sons assumed responsibility for the order's administration.[1]

Succession from Syed Ahmad Ullah

According to German scholar Hans Harder,

The type of spiritual mandate Gholam Rahman had received from Ahmadullah and his status as a saint are a matter of dissent to this day. Writers from Rahmaniyya Manzil, the house of the descendants of Gholam Rahman, class him as a ġawṯ al-aʿẓam, the highest category of a walī Allāh, side by side with Ahmadullah, and sometimes claim that he was installed by Ahmadullah as his spiritual successor (sağğādanašīn). The position held by the descendants of Ahmadullah or Ahmadiyya Manzil, by contrast, is that he was Ahmadullah's main delegate (pradhān khaliphā), and the title of a ġawṯ al-aʿẓam is usually denied to him even if it does appear in one of Delawar Hosain's writings.[1]

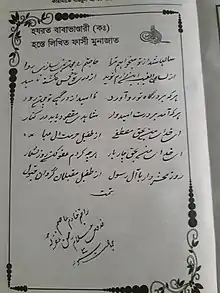

Hand Writing of Baba Bhandari

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Harder, Hans (4 March 2011), Sufism and Saint Veneration in Contemporary Bangladesh: The Maijbhandaris of Chittagong, Routledge (published 2011), pp. 25, 26, ISBN 978-1-136-83189-8

- ↑ Harder, Hans (2011), Sufism and Saint Veneration in Contemporary Bangladesh: The Maijbhandaris of Chittagong, Routledge, pp. 15–22, ISBN 978-1-136-83189-8

- ↑ Bertocci, Peter J. (February 2006). "A Sufi movement in Bangladesh: The Maijbhandari Tariqa and its Followers". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 40 (1): 9. doi:10.1177/006996670504000101. S2CID 144167466.

External links

- Bertocci, Peter J. (February 2006). "A Sufi movement in Bangladesh: The Maijbhandari Tariqa and its Followers". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 40 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1177/006996670504000101. S2CID 144167466.