| Gorilla | |

|---|---|

| |

| Western gorilla (Gorilla gorilla) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Gorillini |

| Genus: | Gorilla I. Geoffroy, 1852 |

| Type species | |

| Troglodytes gorilla Savage, 1847 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Distribution of gorillas | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Gorillas are herbivorous, predominantly ground-dwelling great apes that inhabit the tropical forests of equatorial Africa. The genus Gorilla is divided into two species: the eastern gorilla and the western gorilla, and either four or five subspecies. The DNA of gorillas is highly similar to that of humans, from 95 to 99% depending on what is included, and they are the next closest living relatives to humans after chimpanzees and bonobos.

Gorillas are the largest living primates, reaching heights between 1.25 and 1.8 metres, weights between 100 and 270 kg, and arm spans up to 2.6 metres, depending on species and sex. They tend to live in troops, with the leader being called a silverback. The eastern gorilla is distinguished from the western by darker fur colour and some other minor morphological differences. Gorillas tend to live 35–40 years in the wild.

Gorillas' natural habitats cover tropical or subtropical forest in Sub-Saharan Africa. Although their range covers a small percentage of Sub-Saharan Africa, gorillas cover a wide range of elevations. The mountain gorilla inhabits the Albertine Rift montane cloud forests of the Virunga Volcanoes, ranging in altitude from 2,200 to 4,300 metres (7,200 to 14,100 ft). Lowland gorillas live in dense forests and lowland swamps and marshes as low as sea level, with western lowland gorillas living in Central West African countries and eastern lowland gorillas living in the Democratic Republic of the Congo near its border with Rwanda.

There are thought to be around 316,000 western gorillas in the wild, and 5,000 eastern gorillas. Both species are classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN; all subspecies are classified as Critically Endangered with the exception of the mountain gorilla, which is classified as Endangered. There are many threats to their survival, such as poaching, habitat destruction, and disease, which threaten the survival of the species. However, conservation efforts have been successful in some areas where they live.

Etymology

The word gorilla comes from the history of Hanno the Navigator (c. 500 BC), a Carthaginian explorer on an expedition to the west African coast to the area that later became Sierra Leone.[1][2] Members of the expedition encountered "savage people, the greater part of whom were women, whose bodies were hairy, and whom our interpreters called Gorillae".[3][4] It is unknown whether what the explorers encountered were what we now call gorillas, another species of ape or monkeys, or humans.[5] Skins of gorillai women, brought back by Hanno, are reputed to have been kept at Carthage until Rome destroyed the city 350 years later at the end of the Punic Wars, 146 BC.

The American physician and missionary Thomas Staughton Savage and naturalist Jeffries Wyman first described the western gorilla in 1847 from specimens obtained in Liberia.[6] They called it Troglodytes gorilla, using the then-current name of the chimpanzee genus. The species name was derived from Ancient Greek Γόριλλαι (gorillai) 'tribe of hairy women',[7] as described by Hanno.

Evolution and classification

The closest relatives of gorillas are the other two Homininae genera, chimpanzees and humans, all of them having diverged from a common ancestor about 7 million years ago.[8] Human gene sequences differ only 1.6% on average from the sequences of corresponding gorilla genes, but there is further difference in how many copies each gene has.[9]

| Phylogeny of superfamily Hominoidea[10]: Fig. 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Until recently, gorillas were considered to be a single species, with three subspecies: the western lowland gorilla, the eastern lowland gorilla and the mountain gorilla.[5][11] There is now agreement that there are two species, each with two subspecies.[12] More recently, a third subspecies has been claimed to exist in one of the species. The separate species and subspecies developed from a single type of gorilla during the Ice Age, when their forest habitats shrank and became isolated from each other.[13] Primatologists continue to explore the relationships between various gorilla populations.[5] The species and subspecies listed here are the ones upon which most scientists agree.[14][12]

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern gorilla

|

G. beringei Matschie, 1903 Two subspecies

|

Central Africa |

Size: 160–196 cm (63–77 in) long[15] Habitat: Forest[16] Diet: Roots, leaves, stems, and pith, as well as bark, wood, flowers, fruit, fungi, galls, invertebrates, and gorilla dung[17] |

CR

|

| Western gorilla

|

G. gorilla (Savage, 1847) Two subspecies

|

Western Africa |

Size: 130–185 cm (51–73 in) long[18] Habitat: Forest[19] Diet: Leaves, berries, ferns, and fibrous bark[20] |

CR

|

The proposed third subspecies of Gorilla beringei, which has not yet received a trinomen, is the Bwindi population of the mountain gorilla, sometimes called the Bwindi gorilla.

Some variations that distinguish the classifications of gorilla include varying density, size, hair colour, length, culture, and facial widths.[13] Population genetics of the lowland gorillas suggest that the western and eastern lowland populations diverged around 261 thousand years ago.[21]

Characteristics

Wild male gorillas weigh 136 to 227 kg (300 to 500 lb), while adult females weigh 68–113 kg (150–250 lb).[22][23] Adult males are 1.4 to 1.8 m (4 ft 7 in to 5 ft 11 in) tall, with an arm span that stretches from 2.3 to 2.6 m (7 ft 7 in to 8 ft 6 in). Female gorillas are shorter at 1.25 to 1.5 m (4 ft 1 in to 4 ft 11 in), with smaller arm spans.[24][25][26][27] Colin Groves (1970) calculated the average weight of 42 wild adult male gorillas at 144 kg, while Smith and Jungers (1997) found the average weight of 19 wild adult male gorillas to be 169 kg.[28][29] Adult male gorillas are known as silverbacks due to the characteristic silver hair on their backs reaching to the hips. The tallest gorilla recorded was a 1.95 m (6 ft 5 in) silverback with an arm span of 2.7 m (8 ft 10 in), a chest of 1.98 m (6 ft 6 in), and a weight of 219 kg (483 lb), shot in Alimbongo, northern Kivu in May 1938.[27] The heaviest gorilla recorded was a 1.83 m (6 ft 0 in) silverback shot in Ambam, Cameroon, which weighed 267 kg (589 lb).[27] Males in captivity can be overweight and reach weights up to 310 kg (683 lb).[27]

The eastern gorilla is more darkly coloured than the western gorilla, with the mountain gorilla being the darkest of all. The mountain gorilla also has the thickest hair. The western lowland gorilla can be brown or greyish with a reddish forehead. In addition, gorillas that live in lowland forest are more slender and agile than the more bulky mountain gorillas. The eastern gorilla also has a longer face and broader chest than the western gorilla.[30] Like humans, gorillas have individual fingerprints.[31][32] Their eye colour is dark brown, framed by a black ring around the iris. Gorilla facial structure is described as mandibular prognathism, that is, the mandible protrudes farther out than the maxilla. Adult males also have a prominent sagittal crest.

Gorillas move around by knuckle-walking, although they sometimes walk upright for short distances, typically while carrying food or in defensive situations. A 2018 study investigating the hand posture of 77 mountain gorillas at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (8% of the population) found that knuckle walking was done only 60% of the time, and they also supported their weight on their fists, the backs of their hands/feet, and on their palms/soles (with the digits flexed). Such a range of hand postures was previously thought to have been used by only orangutans.[33] Studies of gorilla handedness have yielded varying results, with some arguing for no preference for either hand, and others right-hand dominance for the general population.[34]

Studies have shown gorilla blood is not reactive to anti-A and anti-B monoclonal antibodies, which would, in humans, indicate type O blood. Due to novel sequences, though, it is different enough to not conform with the human ABO blood group system, into which the other great apes fit.[35]

A gorilla's lifespan is normally between 35 and 40 years, although zoo gorillas may live for 50 years or more. Colo, a female western gorilla at the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, was the oldest known gorilla at 60 years of age when she died on 17 January 2017.[36] Another gorilla, Ozzie, was 61 years old at the time of his death in January 2022.[37]

Distribution and habitat

Gorillas have a patchy distribution. The range of the two species is separated by the Congo River and its tributaries. The western gorilla lives in west central Africa, while the eastern gorilla lives in east central Africa. Between the species, and even within the species, gorillas live in a variety of habitats and elevations. Gorilla habitat ranges from montane forest to swampland. Eastern gorillas inhabit montane and submontane forests between 650 and 4,000 m (2,130 and 13,120 ft) above sea level.[38]

Mountain gorillas live in montane forests at the higher end of the elevation range, while eastern lowland gorillas live in submontane forests at the lower end. In addition, eastern lowland gorillas live in montane bamboo forests, as well as lowland forests ranging from 600–3,308 m (1,969–10,853 ft) in elevation.[39] Western gorillas live in both lowland swamp forests and montane forests, at elevations ranging from sea level to 1,600 m (5,200 ft).[38] Western lowland gorillas live in swamp and lowland forests ranging up to 1,600 m (5,200 ft), and Cross River gorillas live in low-lying and submontane forests ranging from 150–1,600 m (490–5,250 ft).

Ecology

Diet and foraging

A gorilla's day is divided between rest periods and travel or feeding periods. Diets differ between and within species. Mountain gorillas mostly eat foliage, such as leaves, stems, pith, and shoots, while fruit makes up a very small part of their diets.[40] Mountain gorilla food is widely distributed and neither individuals nor groups have to compete with one another. Their home ranges vary from 3 to 15 km2 (1.2 to 5.8 sq mi), and their movements range around 500 m (0.31 mi) or less on an average day.[40] Despite eating a few species in each habitat, mountain gorillas have flexible diets and can live in a variety of habitats.[40]

Eastern lowland gorillas have more diverse diets, which vary seasonally. Leaves and pith are commonly eaten, but fruits can make up as much as 25% of their diets. Since fruit is less available, lowland gorillas must travel farther each day, and their home ranges vary from 2.7 to 6.5 km2 (1.0 to 2.5 sq mi), with day ranges 154–2,280 m (0.096–1.417 mi). Eastern lowland gorillas will also eat insects, preferably ants.[41] Western lowland gorillas depend on fruits more than the others and they are more dispersed across their range.[42] They travel even farther than the other gorilla subspecies, at 1,105 m (0.687 mi) per day on average, and have larger home ranges of 7–14 km2 (2.7–5.4 sq mi).[42] Western lowland gorillas have less access to terrestrial herbs, although they can access aquatic herbs in some areas. Termites and ants are also eaten.

Gorillas rarely drink water "because they consume succulent vegetation that is comprised of almost half water as well as morning dew",[43] although both mountain and lowland gorillas have been observed drinking.

Nesting

Gorillas construct nests for daytime and night use. Nests tend to be simple aggregations of branches and leaves about 2 to 5 ft (0.61 to 1.52 m) in diameter and are constructed by individuals. Gorillas, unlike chimpanzees or orangutans, tend to sleep in nests on the ground. The young nest with their mothers, but construct nests after three years of age, initially close to those of their mothers.[44] Gorilla nests are distributed arbitrarily and use of tree species for site and construction appears to be opportunistic.[45] Nest-building by great apes is now considered to be not just animal architecture, but as an important instance of tool use.[45]

Gorillas make a new nest to sleep on daily and do not use the previous one. This even if remaining in the same place. Usually, they are made an hour before dusk, to be ready to sleep when night falls. Gorillas sleep longer than humans, an average of 12 hours per day.[46]

Interspecies interactions

One possible predator of gorillas is the leopard. Gorilla remains have been found in leopard scat, but this may be the result of scavenging.[47] When the group is attacked by humans, leopards, or other gorillas, an individual silverback will protect the group, even at the cost of his own life.[48] Gorillas do not appear to directly compete with chimpanzees in areas where they overlap. When fruit is abundant, gorilla and chimpanzee diets converge, but when fruit is scarce gorillas resort to vegetation.[49] The two apes may also feed on different species, whether fruit or insects.[50][51][52] Gorillas and chimpanzees may ignore or avoid each other when feeding on the same tree,[49][53] but they have also been documented to form social bonds.[54] Conversely, coalitions of chimpanzees have been observed attacking families of gorillas including silverbacks and killing infants.[55]

Behaviour

Social structure

Gorillas live in groups called troops. Troops tend to be made of one adult male or silverback, with a harem of multiple adult females and their offspring.[56][57][58] However, multiple-male troops also exist.[57] A silverback is typically more than 12 years of age, and is named for the distinctive patch of silver hair on his back, which comes with maturity. Silverbacks have large canine teeth that also come with maturity. Both males and females tend to emigrate from their natal groups. For mountain gorillas, females disperse from their natal troops more than males.[56][59] Mountain gorillas and western lowland gorillas also commonly transfer to second new groups.[56]

Mature males also tend to leave their groups and establish their own troops by attracting emigrating females. However, male mountain gorillas sometimes stay in their natal troops and become subordinate to the silverback. If the silverback dies, these males may be able to become dominant or mate with the females. This behaviour has not been observed in eastern lowland gorillas. In a single male group, when the silverback dies, the females and their offspring disperse and find a new troop.[59][60] Without a silverback to protect them, the infants will likely fall victim to infanticide. Joining a new group is likely to be a tactic against this.[59][61] However, while gorilla troops usually disband after the silverback dies, female eastern lowlands gorillas and their offspring have been recorded staying together until a new silverback transfers into the group. This likely serves as protection from leopards.[60]

The silverback is the centre of the troop's attention, making all the decisions, mediating conflicts, determining the movements of the group, leading the others to feeding sites, and taking responsibility for the safety and well-being of the troop. Younger males subordinate to the silverback, known as blackbacks, may serve as backup protection. Blackbacks are aged between 8 and 12 years[58] and lack the silver back hair. The bond that a silverback has with his females forms the core of gorilla social life. Bonds between them are maintained by grooming and staying close together.[62] Females form strong relationships with males to gain mating opportunities and protection from predators and infanticidal outside males.[63] However, aggressive behaviours between males and females do occur, but rarely lead to serious injury. Relationships between females may vary. Maternally related females in a troop tend to be friendly towards each other and associate closely. Otherwise, females have few friendly encounters and commonly act aggressively towards each other.[56]

Females may fight for social access to males and a male may intervene.[62] Male gorillas have weak social bonds, particularly in multiple-male groups with apparent dominance hierarchies and strong competition for mates. Males in all-male groups, though, tend to have friendly interactions and socialise through play, grooming, and staying together,[58] and occasionally they even engage in homosexual interactions.[64] Severe aggression is rare in stable groups, but when two mountain gorilla groups meet the two silverbacks can sometimes engage in a fight to the death, using their canines to cause deep, gaping injuries.[65]

Reproduction and parenting

Females mature at 10–12 years (earlier in captivity), and males at 11–13 years. A female's first ovulatory cycle occurs when she is six years of age, and is followed by a two-year period of adolescent infertility.[66] The estrous cycle lasts 30–33 days, with outward ovulation signs subtle compared to those of chimpanzees. The gestation period lasts 8.5 months. Female mountain gorillas first give birth at 10 years of age and have four-year interbirth intervals.[66] Males can be fertile before reaching adulthood. Gorillas mate year round.[67]

Females will purse their lips and slowly approach a male while making eye contact. This serves to urge the male to mount her. If the male does not respond, then she will try to attract his attention by reaching towards him or slapping the ground.[68] In multiple-male groups, solicitation indicates female preference, but females can be forced to mate with multiple males.[68] Males incite copulation by approaching a female and displaying at her or touching her and giving a "train grunt".[67] Recently, gorillas have been observed engaging in face-to-face sex, a trait once considered unique to humans and bonobos.[69]

Gorilla infants are vulnerable and dependent, thus mothers, their primary caregivers, are important to their survival.[61] Male gorillas are not active in caring for the young, but they do play a role in socialising them to other youngsters.[70] The silverback has a largely supportive relationship with the infants in his troop and shields them from aggression within the group.[70] Infants remain in contact with their mothers for the first five months and mothers stay near the silverback for protection.[70] Infants suckle at least once per hour and sleep with their mothers in the same nest.[71]

Infants begin to break contact with their mothers after five months, but only for a brief period each time. By 12 months old, infants move up to five m (16 ft) from their mothers. At around 18–21 months, the distance between mother and offspring increases and they regularly spend time away from each other.[72] In addition, nursing decreases to once every two hours.[71] Infants spend only half of their time with their mothers by 30 months. They enter their juvenile period at their third year, and this lasts until their sixth year. At this time, gorillas are weaned and they sleep in a separate nest from their mothers.[70] After their offspring are weaned, females begin to ovulate and soon become pregnant again.[70][71] The presence of play partners, including the silverback, minimizes conflicts in weaning between mother and offspring.[72]

Communication

Twenty-five distinct vocalisations are recognised, many of which are used primarily for group communication within dense vegetation. Sounds classified as grunts and barks are heard most frequently while traveling, and indicate the whereabouts of individual group members.[73] They may also be used during social interactions when discipline is required. Screams and roars signal alarm or warning, and are produced most often by silverbacks. Deep, rumbling belches suggest contentment and are heard frequently during feeding and resting periods. They are the most common form of intragroup communication.[65]

For this reason, conflicts are most often resolved by displays and other threat behaviours that are intended to intimidate without becoming physical. As a result, fights do not occur very frequently. The ritualized charge display is unique to gorillas. The entire sequence has nine steps: (1) progressively quickening hooting, (2) symbolic feeding, (3) rising bipedally, (4) throwing vegetation, (5) chest-beating with cupped hands, (6) one leg kick, (7) sideways running, two-legged to four-legged, (8) slapping and tearing vegetation, and (9) thumping the ground with palms to end display.[74]

A gorilla's chest-beat may vary in frequency depending on its size. Smaller ones tend to have higher frequencies, while larger ones tend to be lower. They also do it the most when females are ready to mate.[75]

Intelligence

Gorillas are considered highly intelligent. A few individuals in captivity, such as Koko, have been taught a subset of sign language. Like the other great apes, gorillas can laugh, grieve, have "rich emotional lives", develop strong family bonds, make and use tools, and think about the past and future.[76] Some researchers believe gorillas have spiritual feelings or religious sentiments.[13] They have been shown to have cultures in different areas revolving around different methods of food preparation, and will show individual colour preferences.[13]

Tool use

The following observations were made by a team led by Thomas Breuer of the Wildlife Conservation Society in September 2005. Gorillas are now known to use tools in the wild. A female gorilla in the Nouabalé-Ndoki National Park in the Republic of Congo was recorded using a stick as if to gauge the depth of water whilst crossing a swamp. A second female was seen using a tree stump as a bridge and also as a support whilst fishing in the swamp. This means all of the great apes are now known to use tools.[77]

In September 2005, a two-and-a-half-year-old gorilla in the Republic of Congo was discovered using rocks to smash open palm nuts inside a game sanctuary.[78] While this was the first such observation for a gorilla, over 40 years previously, chimpanzees had been seen using tools in the wild 'fishing' for termites. Nonhuman great apes are endowed with semiprecision grips, and have been able to use both simple tools and even weapons, such as improvising a club from a convenient fallen branch.

Scientific study

American physician and missionary Thomas Staughton Savage obtained the first specimens (the skull and other bones) during his time in Liberia.[6] The first scientific description of gorillas dates back to an article by Savage and the naturalist Jeffries Wyman in 1847 in Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History,[79][80] where Troglodytes gorilla is described, now known as the western gorilla. Other species of gorilla were described in the next few years.[5]

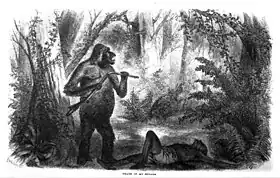

The explorer Paul Du Chaillu was the first westerner to see a live gorilla during his travel through western equatorial Africa from 1856 to 1859. He brought dead specimens to the UK in 1861.[81][82][83]

The first systematic study was not conducted until the 1920s, when Carl Akeley of the American Museum of Natural History traveled to Africa to hunt for an animal to be shot and stuffed. On his first trip, he was accompanied by his friends Mary Bradley, a mystery writer, her husband, and their young daughter Alice, who would later write science fiction under the pseudonym James Tiptree Jr. After their trip, Mary Bradley wrote On the Gorilla Trail. She later became an advocate for the conservation of gorillas, and wrote several more books (mainly for children). In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Robert Yerkes and his wife Ava helped further the study of gorillas when they sent Harold Bigham to Africa. Yerkes also wrote a book in 1929 about the great apes.

After World War II, George Schaller was one of the first researchers to go into the field and study primates. In 1959, he conducted a systematic study of the mountain gorilla in the wild and published his work. Years later, at the behest of Louis Leakey and the National Geographic, Dian Fossey conducted a much longer and more comprehensive study of the mountain gorilla. When she published her work, many misconceptions and myths about gorillas were finally disproved, including the myth that gorillas are violent.

Western lowland gorillas (G. g. gorilla) are believed to be one of the zoonotic origins of HIV/AIDS. The SIVgor Simian immunodeficiency virus that infects them is similar to a certain strain of HIV-1.[84][85][86][87]

Genome sequencing

The gorilla became the next-to-last great ape genus to have its genome sequenced. The first gorilla genome was generated with short read and Sanger sequencing using DNA from a female western lowland gorilla named Kamilah. This gave scientists further insight into the evolution and origin of humans. Despite the chimpanzees being the closest extant relatives of humans, 15% of the human genome was found to be more like that of the gorilla.[88] In addition, 30% of the gorilla genome "is closer to human or chimpanzee than the latter are to each other; this is rarer around coding genes, indicating pervasive selection throughout great ape evolution, and has functional consequences in gene expression."[89] Analysis of the gorilla genome has cast doubt on the idea that the rapid evolution of hearing genes gave rise to language in humans, as it also occurred in gorillas.[90]

Captivity

.jpg.webp)

Gorillas became highly prized by western zoos since the 19th century, though the earliest attempts to keep them in captive facilities ended in their early death. In the late 1920s the care of captive gorillas significantly improved.[91] Colo (December 22, 1956 – January 17, 2017) of the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium was the first gorilla to be born in captivity.[92]

Captive gorillas exhibit stereotypic behaviors, including eating disorders—such as regurgitation, reingestion and coprophagy—self-injurious or conspecific aggression, pacing, rocking, sucking of fingers or lip smacking, and overgrooming.[93] Negative vigilance of visitor behaviors have been identified as starting, posturing and charging at visitors.[94] Groups of bachelor gorillas containing young silverbacks have significantly higher levels of aggression and wounding rates than mixed age and sex groups.[95][96]

The use of both internal and external privacy screens on exhibit windows has been shown to alleviate stresses from visual effects of high crowd densities, leading to decreased stereotypic behaviors in the gorillas.[94] Playing naturalistic auditory stimuli as opposed to classical music, rock music, or no auditory enrichment (which allows for crowd noise, machinery, etc. to be heard) has been noted to reduce stress behavior as well.[97] Enrichment modifications to feed and foraging, where clover-hay is added to an exhibit floor, decrease stereotypic activities while simultaneously increasing positive food-related behaviors.[94]

Recent research on captive gorilla welfare emphasizes a need to shift to individual assessments instead of a one-size-fits-all group approach to understanding how welfare increases or decreases based on a variety of factors.[96] Individual characteristics such as age, sex, personality and individual histories are essential in understanding that stressors will affect each individual gorilla and their welfare differently.[94][96]

Conservation status

All species (and subspecies) of gorilla are listed as endangered or critically endangered on the IUCN Red List.[98][99] All gorillas are listed in Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), meaning that international export/import of the species, including in parts and derivatives, is regulated.[100] Around 316,000 western lowland gorillas are thought to exist in the wild,[101] 4,000 in zoos, thanks to conservation; eastern lowland gorillas have a population of under 5,000 in the wild and 24 in zoos. Mountain gorillas are the most severely endangered, with an estimated population of about 880 left in the wild and none in zoos.[13][98] Threats to gorilla survival include habitat destruction and poaching for the bushmeat trade. Gorillas are closely related to humans, and are susceptible to diseases that humans also get infected by. In 2004, a population of several hundred gorillas in the Odzala National Park, Republic of Congo was essentially wiped out by the Ebola virus.[102] A 2006 study published in Science concluded more than 5,000 gorillas may have died in recent outbreaks of the Ebola virus in central Africa. The researchers indicated in conjunction with commercial hunting of these apes, the virus creates "a recipe for rapid ecological extinction".[103] In captivity, it has also been observed that gorillas can also be infected with COVID-19.[104]

Conservation efforts include the Great Apes Survival Project, a partnership between the United Nations Environment Programme and the UNESCO, and also an international treaty, the Agreement on the Conservation of Gorillas and Their Habitats, concluded under UNEP-administered Convention on Migratory Species. The Gorilla Agreement is the first legally binding instrument exclusively targeting gorilla conservation; it came into effect on 1 June 2008. Governments of countries where gorillas live placed a ban on their killing and trading, but weak law enforcement still poses a threat to them, since the governments rarely apprehend poachers, traders and consumers that rely on gorillas for profit.[105]

Cultural significance

In Cameroon's Lebialem highlands, folk stories connect people and gorillas via totems; a gorilla's death means the connected person will die also. This creates a local conservation ethic.[106] Many different indigenous peoples interact with wild gorillas.[106] Some have detailed knowledge; the Baka have words to distinguish at least ten types of gorilla individuals, by sex, age, and relationships.[106] In 1861, alongside tales of hunting enormous gorillas, the traveller and anthropologist Paul Du Chaillu reported the Cameroonian story that a pregnant woman who sees a gorilla will give birth to one.[106][107]

In 1911, the anthropologist Albert Jenks noted the Bulu people's knowledge of gorilla behaviour and ecology, and their gorilla stories. In one such story, "The Gorilla and the Child", a gorilla speaks to people, seeking help and trust, and stealing a baby; a man accidentally kills the baby while attacking the gorilla.[106] Even far from where gorillas live, savannah tribes pursue "cult-like worship" of the apes.[106][108] Some beliefs are widespread among indigenous peoples. The Fang name for gorilla is ngi while the Bulu name is njamong; the root ngi means fire, denoting a positive energy. From the Central African Republic to Cameroon and Gabon, stories of reincarnations as gorillas, totems, and transformations similar to those recorded by Du Chaillu are still told in the 21st century.[106]

Since gaining international attention, gorillas have been a recurring element of many aspects of popular culture and media.[109] They were usually portrayed as murderous and aggressive. Inspired by Emmanuel Frémiet's Gorilla Carrying off a Woman, gorillas have been depicted kidnapping human women.[110] This theme was used in films such as Ingagi (1930) and most notably King Kong (1933).[111] The comedic play The Gorilla, which debuted in 1925, featured an escaped gorilla taking a woman from her house.[112] Several films would use the "escaped gorilla" trope including The Strange Case of Doctor Rx (1942), The Gorilla Man (1943), Gorilla at Large (1954) and the Disney cartoons The Gorilla Mystery (1930) and Donald Duck and the Gorilla (1944).[113]

Gorillas have been used as opponents to jungle-themed heroes such as Tarzan and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle,[114] as well as superheroes. The DC comics supervillain Gorilla Grodd is an enemy of the Flash.[115] Gorillas also serve as antagonists in the 1968 film Planet of the Apes.[116] More positive and sympathetic portrayals of gorillas include the films Son of Kong (1933), Mighty Joe Young (1949), Gorillas in the Mist (1988) and Instinct (1999) and the 1992 novel Ishmael.[117] Gorillas have been featured in video games as well, notably Donkey Kong.[115]

See also

- Bili ape

- Gorilla (advertisement)

- Gorilla suit

- Great Ape Project

- Harambe – a captive gorilla, shot while interacting with a child who fell into his zoo enclosure, who became a popular internet meme

- International Primate Day

- List of individual apes

- List of fictional apes

- Monkey Day

References

- ↑ Müller, C. (1855–1861). Geographi graeci minores. pp. 1.1–14: text and trans. Ed. J. Blomqvist (1979).

- ↑ Hair, P. E. H. (1987). "The Periplus of Hanno in the history and historiography of Black Africa". History in Africa. 14: 43–66. doi:10.2307/3171832. JSTOR 3171832. S2CID 162671887.

- ↑ "A carthaginian exploration of the West African coast". Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- ↑ Montagu, M. F. A. (1940). "Knowledge of the Ape in Antiquity". Isis. 32 (1): 87–102. doi:10.1086/347644. S2CID 143874276.

- 1 2 3 4 Groves, C. (2002). "A history of gorilla taxonomy" (PDF). In Taylor, A. B.; Goldsmith, M. L. (eds.). Gorilla biology: A multidisciplinary perspective. Cambridge University Press. pp. 15–34. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- 1 2 Conniff, R. (2009). "Discovering gorilla". Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 18 (2): 55–61. doi:10.1002/evan.20203. S2CID 221732306.

- ↑ Liddell, H. G.; Scott, R. "Γόριλλαι". A Greek-English lexicon. Perseus Digital Library. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011.

- ↑ Glazko, G. V.; Nei, Masatoshi (March 2003). "Estimation of divergence times for major lineages of primate species". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 20 (3): 424–434. doi:10.1093/molbev/msg050. PMID 12644563.

- ↑ Goidts, V.; Armengol, L.; Schempp, W.; et al. (March 2006). "Identification of large-scale human-specific copy number differences by inter-species array comparative genomic hybridization". Human Genetics. 119 (1–2): 185–198. doi:10.1007/s00439-005-0130-9. PMID 16395594. S2CID 32184430.

- ↑ Israfil, H.; Zehr, S. M.; Mootnick, A. R.; Ruvolo, M.; Steiper, M. E. (2011). "Unresolved molecular phylogenies of gibbons and siamangs (Family: Hylobatidae) based on mitochondrial, Y-linked, and X-linked loci indicate a rapid Miocene radiation or sudden vicariance event" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (3): 447–455. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.005. PMC 3046308. PMID 21074627. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2012.

- ↑ Stewart, K. J.; Sicotte, P.; Robbins, M. M. (2001). "Mountain gorillas of the Virungas". Fathom / Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 11 September 2008.

- 1 2 Mittermeier, R. A.; Rylands, A. B.; Wilson, D. E., eds. (2013). Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 3. Primates. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-8496553897.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Prince-Hughes, D. (1987). Songs of the gorilla nation. Harmony. p. 66. ISBN 978-1400050581.

- ↑ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 181–182. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Kingdon, p. 93

- 1 2 Plumptre, A.; Robbins, M. M.; Williamson, E. A. (2019). "Gorilla beringei". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T39994A115576640. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T39994A115576640.en.

- ↑ Lindsley, Tracy; Sorin, Anna Bess (2001). "Gorilla beringei". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 30 August 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ↑ Kingdon, p. 91

- 1 2 Maisels, F.; Bergl, R. A.; Williamson, E. A. (2018) [amended version of 2016 assessment]. "Gorilla gorilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T9404A136250858. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T9404A136250858.en.

- ↑ Csomos, Rebecca Ann (2008). "Gorilla gorilla". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ↑ McManus, K. F.; Kelley, J. L.; Song, S.; et al. (2015). "Inference of gorilla demographic and selective history from whole-genome sequence data". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 32 (3): 600–612. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu394. PMC 4327160. PMID 25534031.

- ↑ Aryan, H. E. (2006). "Lumbar diskectomy in a human-habituated mountain gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei)". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 108 (2): 205–210. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2004.12.011. PMID 16412845. S2CID 29723690.

- ↑ Miller, Patricia (1997). Gorillas. Weigl Educational Publishers. p. 64. ISBN 978-0919879898. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016.

- ↑ Wood, B. A. (1978). "Relationship between body size and long bone lengths in Pan and Gorilla". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 50 (1): 23–25. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330500104. PMID 736111.

- ↑ Leigh, S. R.; Shea, B. T. (1995). "Ontogeny and the evolution of adult body size dimorphism in apes". American Journal of Primatology. 36 (1): 37–60. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350360104. PMID 31924084. S2CID 85136825.

- ↑ Tuttle, R. H. (1986). Apes of the world: their social behavior, communication, mentality and ecology. William Andrew. ISBN 978-0815511045.

- 1 2 3 4 Wood, G. L. (1983). The Guinness book of animal facts and feats. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 978-0851122359.

- ↑ Smith, R. J.; Jungers, W. L. (1997). "Body mass in comparative primatology". Journal of Human Evolution. 32 (6): 523–559. doi:10.1006/jhev.1996.0122. PMID 9210017.

- ↑ Groves, C. P. (July 1970). "Population systematics of the gorilla". Journal of Zoology. 161 (3): 287–300. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1970.tb04514.x – via Onlinelibrary.

- ↑ Rowe, N. (1996). Pictorial guide to the living primates. East Hampton, NY: Pogonias Press.

- ↑ "Santa Barbara Zoo – western lowland gorilla". Santa Barbara Zoo. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ↑ "Gorillas". Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010.

- ↑ Thompson, N. E.; Ostrofsky, K. R.; McFarlin, S. C.; Robbins, M. M.; Stoinski, T. S.; Almécija, S. (2018). "Unexpected terrestrial hand posture diversity in wild mountain gorillas". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 166 (1): 84–94. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23404. PMID 29344933.

- ↑ Fagot, J.; Vauclair, J. (1988). "Handedness and bimanual coordination in the lowland gorilla". Brain, Behavior and Evolution. 32 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1159/000116536. PMID 3179697.

- ↑ Gamble, K. C.; Moyse, J. A.; Lovstad, J. N.; Ober, C. B.; Thompson, E. E. (2011). "Blood groups in the Species Survival Plan, European Endangered Species Program, and managed in situ populations of bonobo (Pan paniscus), common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), gorilla (Gorilla ssp.), and orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus ssp.)" (PDF). Zoo Biology. 30 (4): 427–444. doi:10.1002/zoo.20348. PMC 4258062. PMID 20853409. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

- ↑ "Columbus Zoo announces the death of Colo, world's oldest zoo gorilla". Columbus Zoo. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ↑ Jackson, Amanda (26 January 2022). "Ozzie, the world's oldest male gorilla, has died at Zoo Atlanta". CNN. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- 1 2 Sarmiento, E. E. (2003). "Distribution, taxonomy, genetics, ecology, and causal links of gorilla survival: the need to develop practical knowledge for gorilla conservation". In Taylor, A. B.; Goldsmith, M. L. (eds.). Gorilla biology: a multidisciplinary perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 432–471.

- ↑ Ilambu, O. (2001). "Ecology of eastern lowland gorilla: is there enough scientific knowledge to mitigate conservation threats associated with extreme disturbances in its distribution range?". The apes: challenges for the 21st century. Brookfield, IL, USA: Chicago Zoological Society. pp. 307–312.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 McNeilage 2001, pp. 265–292.

- ↑ Yamagiwa, J.; Mwanza, N.; Yumoto, T.; Maruhashi, T. (1994). "Seasonal change in the composition of the diet of eastern lowland gorillas". Primates. 35: 1–14. doi:10.1007/BF02381481. S2CID 33021914.

- 1 2 Tutin, C. G. (1996). "Ranging and social structure of lowland gorillas in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon". In McGrew, W. C.; Marchant, L. F.; Nishida, T. (eds.). Great Ape Societies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–70.

- ↑ "Gorillas – diet & eating habits". Seaworld. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ↑ Miller-Schroeder, P. (1997). Gorillas. Weigl Educational Publishers Limited. p. 20. ISBN 978-0919879898. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- 1 2 Marchant, L. F.; Nishida, T. (1996). Great ape societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 226–227. ISBN 978-0521555364. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ↑ "Gorilla Night Routines". Gorilla Fund. 18 October 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ↑ Fay, J. M.; Carroll, R.; Kerbis Peterhans, J. C.; Harris, D. (1995). "Leopard attack on and consumption of gorillas in the Central African Republic". Journal of Human Evolution. 29 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1006/jhev.1995.1048. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012.

- ↑ "Wildlife: mountain gorilla". AWF. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- 1 2 Tutin, C. E. G.; Fernandez, M. (1993). "Composition of the diet of chimpanzees and comparisons with that of sympatric lowland gorillas in the Lopé reserve, Gabon". American Journal of Primatology. 30 (3): 195–211. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350300305. PMID 31937009. S2CID 84681736.

- ↑ Stanford, C. B.; Nkurunungi, J. B. (2003). "Behavioral ecology of sympatric chimpanzees and gorillas in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda: diet". International Journal of Primatology. 24 (4): 901–918. doi:10.1023/A:1024689008159. S2CID 22587913.

- ↑ Tutin, C. E. G.; Fernandez, M. (1992). "Insect-eating by sympatric lowland gorillas (Gorilla g. gorilla) and chimpanzees (Pan t. troglodytes) in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon". American Journal of Primatology. 28 (1): 29–40. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350280103. PMID 31941221. S2CID 85569302.

- ↑ Deblauwe, I. (2007). "New insights in insect prey choice by chimpanzees and gorillas in Southeast Cameroon: The role of nutritional value". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 135 (1): 42–55. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20703. PMID 17902166.

- ↑ Galdikas, B. M. (2005). Great ape odyssey. Abrams. p. 89. ISBN 978-1435110090.

- ↑ Sanz, C. M.; et al. (2022). "Interspecific interactions between sympatric apes". iScience. 25 (10): 105059. Bibcode:2022iSci...25j5059S. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.105059. PMC 9485909. PMID 36147956.

- ↑ Southern, L. M.; Deschner, T.; Pika, S. (2021). "Lethal coalitionary attacks of chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) on gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) in the wild". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 14673. Bibcode:2021NatSR..1114673S. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93829-x. PMC 8290027. PMID 34282175.

- 1 2 3 4 Watts, D. P. (1996). "Comparative socio-ecology of gorillas". In McGrew, W. C.; Marchant, L. F.; Nishida, T. (eds.). Great ape societies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–28.

- 1 2 Yamagiwa, J.; Kahekwa, J.; Kanyunyi Basabose, A. (2003). "Intra-specific variation in social organization of gorillas: implications for their social evolution". Primates. 44 (4): 359–369. doi:10.1007/s10329-003-0049-5. PMID 12942370. S2CID 21216499.

- 1 2 3 Robbins 2001, pp. 29–58.

- 1 2 3 Stokes, E. J.; Parnell, R. J.; Olejniczak, C. (2003). "Female dispersal and reproductive success in wild western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 54 (4): 329–339. doi:10.1007/s00265-003-0630-3. JSTOR 25063274. S2CID 21995743.

- 1 2 Yamagiwa & Kahekwa 2001, pp. 89–122.

- 1 2 Watts, D. P. (1989). "Infanticide in mountain gorillas: new cases and a reconsideration of the evidence". Ethology. 81 (1): 1–18. Bibcode:1989Ethol..81....1W. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1989.tb00754.x.

- 1 2 Watts, D. P. (2003). "Gorilla social relationships: a comparative review". In Taylor, A. B.; Goldsmith, M. L. (eds.). Gorilla biology: a multidisciplinary perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 302–327.

- ↑ Watts 2001, pp. 216–240.

- ↑ Yamagiwa, Juichi (1987). "Intra- and inter-group interactions of an all-male group of Virunga mountain gorillas (Gorilla gorilla beringei )". Primates. 28 (1): 1–30. doi:10.1007/BF02382180. S2CID 24667667.

- 1 2 Fossey, D. (1983). Gorillas in the mist. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0395282179.

- 1 2 Czekala & Robbins 2001, pp. 317–339.

- 1 2 Watts, D. P. (1991). "Mountain gorilla reproduction and sexual behavior". American Journal of Primatology. 24 (3–4): 211–225. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350240307. PMID 31952383. S2CID 85023681.

- 1 2 Sicotte 2001, pp. 59–87.

- ↑ Nguyen, T. C. (13 February 2008). "Caught in the act! Gorillas mate face to face". NBC News.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stewart 2001, pp. 183–213.

- 1 2 3 Stewart, K. J. (1988). "Suckling and lactational anoestrus in wild gorillas (Gorilla gorilla)". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility. 83 (2): 627–634. doi:10.1530/jrf.0.0830627. PMID 3411555.

- 1 2 Fletcher 2001, pp. 153–182.

- ↑ Harcourt, A. H.; Stewart, K. J.; Hauser, M. (1993). "Functions of wild gorilla 'close' calls. I. Repertoire, context, and interspecific comparison". Behaviour. 124 (1–2): 89. doi:10.1163/156853993X00524.

- ↑ Maple, T. L.; Hoff, M.P. (1982). Gorilla behavior. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Company.

- ↑ Wright, E.; et al. (2021). "Chest beats as an honest signal of body size in male mountain gorillas (Gorilla beringei beringei)". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 6879. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.6879W. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-86261-8. PMC 8032651. PMID 33833252.

- ↑ "Planet of no apes? Experts warn it's close". CBS News Online. 12 September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ↑ Breuer, T.; Ndoundou-Hockemba, M.; Fishlock, V. (2005). "First observation of tool use in wild gorillas". PLOS Biology. 3 (11): e380. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030380. PMC 1236726. PMID 16187795.

- ↑ "A tough nut to crack for evolution". CBS News Online. 18 October 2005. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ↑ Savage, T. S. (1847). Communication describing the external character and habits of a new species of Troglodytes (T. gorilla). Boston Society of Natural History. pp. 245–247. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016.

- ↑ Savage, T. S; Wyman, J. (1847). "Notice of the external characters and habits of Troglodytes gorilla, a new species of orang from the Gaboon River, osteology of the same". Boston Journal of Natural History. 5 (4): 417–443. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016.

- ↑ McCook, S. (1996). ""It may be truth, but it is not evidence": Paul du Chaillu and the legitimation of evidence in the field sciences" (PDF). Osiris. 11: 177–197. doi:10.1086/368759. hdl:10214/7693. S2CID 143950182. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2017.

- ↑ "A history of Museum Victoria: Melbourne 1865: Gorillas at the museum". Museum Victoria. Archived from the original on 27 February 2008. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- ↑ Quammen, D.; Reel, M. (4 April 2013). "Book review: Planet of the ape - 'Between man and beast". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ Van Heuverswyn, F.; Li, Y.; Neel, C.; et al. (2006). "Human immunodeficiency viruses: SIV infection in wild gorillas". Nature. 444 (7116): 164. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..164V. doi:10.1038/444164a. PMID 17093443. S2CID 27475571.

- ↑ Plantier, J.; Leoz, M.; Dickerson, J. E.; et al. (2009). "A new human immunodeficiency virus derived from gorillas". Nature Medicine. 15 (8): 871–872. doi:10.1038/nm.2016. PMID 19648927. S2CID 76837833.

- ↑ Sharp, P. M.; Bailes, E.; Chaudhuri, R. R.; Rodenburg, C. M.; Santiago, M. O.; Hahn, B. H. (2001). "The origins of acquired immune deficiency syndrome viruses: where and when?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 356 (1410): 867–876. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.0863. PMC 1088480. PMID 11405934.

- ↑ Takebe, Y.; Uenishi, R.; Li, X. (2008). "Global molecular epidemiology of HIV: Understanding the genesis of AIDS pandemic". HIV-1: Molecular biology and pathogenesis. Advances in Pharmacology. Vol. 56. pp. 1–25. doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(07)56001-1. ISBN 978-0123736017. PMID 18086407.

- ↑ Kelland, K. (7 March 2012). "Gorilla genome sheds new light on human evolution". Reuters. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Scally, A.; Dutheil, J. Y.; Hillier, L. W.; et al. (2012). "Insights into hominid evolution from the gorilla genome sequence". Nature. 483 (7388): 169–175. Bibcode:2012Natur.483..169S. doi:10.1038/nature10842. hdl:10261/80788. PMC 3303130. PMID 22398555.

- ↑ Smith, K. (7 March 2012). "Gorilla joins the genome club". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.10185. S2CID 85141639. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 98–107.

- ↑ "Colo, the oldest gorilla in captivity, dies aged 60". BBC News. 18 January 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ↑ Wells, D. L. (2005). "A note on the influence of visitors on the behaviour and welfare of zoo-housed gorillas". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 93 (1–2): 13–17. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.06.019.

- 1 2 3 4 Clark, F.; Fitzpatrick, M.; Hartley, A.; King, A.; Lee, T.; Routh, A.; Walker, S; George, K (2011). "Relationship between behavior, adrenal activity, and environment in zoo-housed western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla)". Zoo Biology. 31 (3): 306–321. doi:10.1002/zoo.20396. PMID 21563213.

- ↑ Leeds, A.; Boyer, D.; Ross, S; Lukas, K. (2015). "The effects of group type and young silverbacks on wounding rates in western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) groups in North American zoos". Zoo Biology. 34 (4): 296–304. doi:10.1002/zoo.21218. PMID 26094937.

- 1 2 3 Stoinski, T.; Jaicks, H.; Drayton, L. (2011). "Visitor effects on the behavior of captive western lowland gorillas: the importance of individual differences in examining welfare". Zoo Biology. 31 (5): 586–599. doi:10.1002/zoo.20425. PMID 22038867.

- ↑ Robbins, L.; Margulis, S. (2014). "The effects of auditory enrichment on gorillas". Zoo Biology. 33 (3): 197–203. doi:10.1002/zoo.21127. PMID 24715297.

- 1 2 "Four out of six great apes one step away from extinction – IUCN Red List". IUCN. 4 September 2016. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Fin whale, mountain gorilla recovering thanks to conservation action – IUCN Red List". International Union for the Conservation of Nature. 14 November 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ↑ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ↑ Maisels, F.; Bergl, R. A.; Williamson, E. A. (2016) [amended version of 2016 assessment]. "Gorilla gorilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T9404A136250858.

- ↑ "Gorillas infecting each other with Ebola". New Scientist. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 12 July 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2006.

- ↑ "Ebola 'kills over 5,000 gorillas'". BBC. 8 December 2006. Archived from the original on 29 March 2009. Retrieved 9 December 2006.

- ↑ Luscombe, Richard (29 September 2021). "Thirteen gorillas test positive for Covid at Atlanta zoo | Atlanta | The Guardian". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 September 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ↑ "Gorilla | Species | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Amir, Adam Pérou Hermans (15 June 2019). "Who Knows What About Gorillas? Indigenous Knowledge, Global Justice, and Human-Gorilla Relations". IK: Other Ways of Knowing. 5: 1–40. doi:10.26209/ik560158. S2CID 202289674.

- ↑ Du Chaillu, Paul (1861). Explorations and Adventures in Equatorial Africa: with Accounts of theManners and Customs of the People, and of the Chace of the Gorilla, the Crocodile, Leopard, Elephant, Hippopotamus and Other Animals. New York: Harper. Chapter 16, page 352.

- ↑ Alesha, Matomah (2004). Sako Ma: A Look at the Sacred Monkey Totem. Tucson: Matam Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-1411606432.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, Chapters 3 and 4.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 122–125.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 138–143.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 131–135.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 89–91, 173.

- 1 2 Gott & Weir 2013, p. 92.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 157, 183.

- ↑ Gott & Weir 2013, pp. 174–176.

Literature cited

- Gott, T.; Weir, K. (2013). Gorilla. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1306124683. OCLC 863158343.

- Robbins, M. M.; Sicotte, P.; Stewart, K. J. (2001). Mountain gorillas: three decades of research at Karisoke. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521019869.

- Czekala, N.; Robbins, M. M. (2001). Assessment of reproduction and stress through hormone analysis in gorillas. pp. 317–339.

- Fletcher, A. (2001). Development of infant independence from the mother in wild mountain gorillas. pp. 153–182.

- McNeilage, A. (2001). Diet and habitat use of two mountain gorilla groups in contrasting habitats in the Virungas. pp. 265–292.

- Robbins, M. M. (2001). Variation in the social system of mountain gorillas: the male perspective. pp. 29–58.

- Sicotte, P. (2001). Robbins (ed.). Female mate choice in mountain gorillas. pp. 59–87.

- Stewart, K. J. (2001). Social relationships of immature gorillas and silverbacks. pp. 183–213.

- Watts, D. P. (2001). Social relationships of female mountain gorillas. pp. 216–240.

- Yamagiwa, J.; Kahekwa, J. (2001). Dispersal patterns, group structure, and reproductive parameters of eastern lowland gorillas at Kahuzi in the absence of infanticide. pp. 89–122.

- Kingdon, Jonathan (2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (Second ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-2531-2.

External links

- Animal Diversity Web – includes photos, artwork, and skull specimens of Gorilla gorilla

- Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting International Gorilla Conservation Programme (Video) (archived 5 September 2007)

- Primate Info Net Gorilla Factsheet Archived 22 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine – taxonomy, ecology, behavior and conservation

- San Diego Zoo Gorilla Factsheet – features a video and photos

- World Wildlife Fund: Gorillas – conservation, facts and photos (archived 16 October 2004)

- Gorilla protection – Gorilla conservation (archived 29 November 2010)

- Welcome to the Year of the Gorilla 2009 Archived 18 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Virunga National Park – The Official Website for Virunga National Park, the Last Refuge for Congo's Mountain Gorillas (archived 22 September 2010)

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).

- Genome of Gorilla gorilla, via Ensembl

- Genome of Gorilla gorilla (version Kamilah_GGO_v0/gorGor6), via UCSC Genome Browser

- Data of the genome of Gorilla gorilla, via NCBI

- Data of the genome assembly of Gorilla gorilla (version Kamilah_GGO_v0/gorGor6), via NCBI

.jpg.webp)