| Mico[1][2] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Silvery marmoset (Mico argentatus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Callitrichidae |

| Genus: | Mico Lesson, 1840 |

| Species | |

|

16, see text | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Mico is a genus of New World monkeys of the family Callitrichidae, the family containing marmosets and tamarins. The genus was formerly considered a subgenus of the genus Callithrix.

Taxonomy

Mico differs from Callithrix in dental morphology, genetics and geographic distribution: Callithrix species are distributed in eastern Brazil (mainly the Atlantic Forest), while Mico species are distributed in the Amazon rainforest south of the lower Amazon and Madeira Rivers, though a single species, the black-tailed marmoset, also occurs in the Pantanal and Chaco.[4] Roosmalens' dwarf marmoset (Mico humilis) was briefly considered to be a member of a new monotypic genus, Callibella, due mainly to differences in size, genetics, and its bearing of a single young rather than the two that marmosets usually bear.[5][6] Roosmalens' dwarf marmoset is significantly smaller than the Mico species, being about midway between the typical Mico species and the pygmy marmoset, Cebuella pygmaea.[5] Mico species differ from the tamarins of the genus Saguinus in that Mico has enlarged incisor teeth the same size as the canine teeth which are used for gouging holes in trees to extract exudates.[7]

Species level taxonomy within Mico has also changed significantly in recent decades. Earlier authorities usually treated all as subspecies of M. argentatus (including the bare-eared taxa) or M. humeralifera (including the hairy-eared taxa), or even suggested all were subspecies of M. argentatus.[8][9][10] Recent authorities have pointed out that several of the taxa are highly distinctive, and following the phylogenetic species concept all previous subspecies were proposed raised to species status in 2001.[11] This has generally been followed since then.[1][2][4] Furthermore, nine of the sixteen currently recognized species were only described to science after 1990.[12] The validity of one species described in 2000, M. manicorensis (the Manicore marmoset), is questionable, as a review found no differences between it and M. marcai (Marca's marmoset),[13] leading the IUCN to treat the former as a synonym of the latter.[14]

Species

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mico acariensis | Rio Acari marmoset | Brazil | |

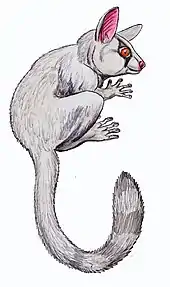

| Mico humilis | Roosmalens' dwarf marmoset | Brazil | |

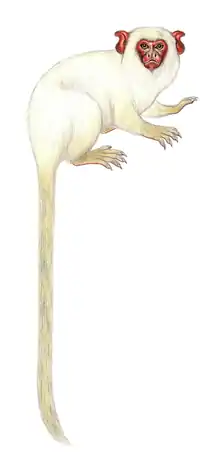

.jpg.webp) | Mico argentatus | Silvery marmoset | eastern Amazon Rainforest in Brazil |

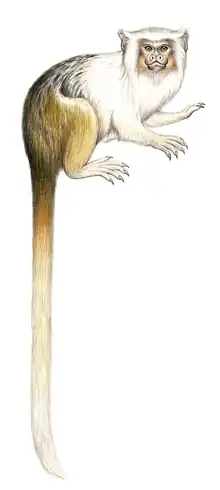

| Mico leucippe | White marmoset | Pará in Brazil |

| Mico emiliae | Emilia's marmoset | Brazilian states of Pará and Mato Grosso |

| Mico nigriceps | Black-headed marmoset | Brazil | |

| Mico marcai | Marca's marmoset | Aripuanã-Manicoré interfluvium in Brazil | |

_Chester_Zoo.jpg.webp) | Mico melanurus | Black-tailed marmoset | south-central Amazon in Brazil, south through the Pantanal and eastern Bolivia, to the Chaco in far northern Paraguay |

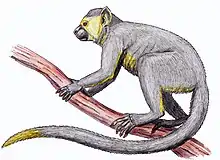

| Mico humeralifer | Santarem marmoset | Brazilian states of Amazonas and Pará |

| Mico mauesi | Maués marmoset | Brazil | |

| Mico munduruku | Munduruku marmoset | Brazilian states of Amazonas and Pará |

| Mico chrysoleucus | Gold-and-white marmoset | eastern Amazon state in Brazil |

| Mico intermedia | Hershkovitz's marmoset | Brazil |

| Mico saterei | Satéré marmoset | Brazil | |

| Mico schneideri | Schneider's marmoset | Brazil |

| Mico rondoni | Rondon's marmoset | Brazil by the Rio Mamoré, Rio Madeira, Rio Ji-Paraná, Serra dos Pacaás Novos |

Ecology

In general, Mico and Callithrix species tend to form larger groups and live within smaller home ranges, and thus live in higher population densities, than other callitrichids. But these statistics can vary dramatically among various Mico species. M. argentatus tends to live in smaller home ranges (as small as 10 hectares or less) than other Mico species.[5]

Exudates, such as gum and sap, fruit, nectar and fungus make up the bulk of Mico's diet, but it also eats animal prey such as arthropods, young birds, small lizards and frogs. They are specialized for exploiting exudates by their elongated, chisel-like lower incisors and a wide jaw gape that allows them to gouge bark of trees that produce gums. Their intestines also have an enlarged, complex cecum that allows them to digest gums more efficiently than most other animals. Mico's ability to feed on exudates allows it to survive in areas where fruit is highly seasonal or not readily available.[5]

Mico females generally gives birth to two or more infants at a time. They can ovulate and conceive within two to four weeks after giving birth, and ovulation is not inhibited by lactation. Females generally reach sexual maturity between 12 and 17 months, and males between 15 and 25 months.[5]

Emilia's marmoset, Mico emiliae, sometimes interacts with the brown-mantled tamarin, Saguinus fuscicollis.[5]

References

- 1 2 Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 129–13. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 Rylands, A. B.; Mittermeier, R. A. (2009). "The diversity of the New World primates (Platyrrhini)". In Garber, P. A.; Estrada, A.; Bicca-Marques, J. C.; Heymann, E. W.; Strier, K. B. (eds.). South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation. Springer. pp. 23–54. ISBN 978-0-387-78704-6.

- ↑ "Mico". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 1 2 Rylands, A. B.; Mittermeier, R. A.; Coimbra-Filho, A. F.; Heymann, E. W.; de la Torre, S.; Silva Jr., J. S.; Kierulff, C. M.; Noronha, M. A.; Röhe, F. (2008). Marmosets and Tamarins: Pocket Identification Guide. Conservation International. ISBN 978-1-934151-20-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Digby, L.; Ferari, S.; Saltzman, W. (2007). "Callitrchines". In Campbell, C.; et al. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. pp. 85–106. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- ↑ van Roosmalen, M. G. M.; van Roosmalen, T. (2003). "The description of a new marmoset genus, Callibella (Callitrichinae, Primates), including its phylogenetic status" (PDF). Neotropical Primates. 11 (1): 1–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2008.

- ↑ Rowe, N. (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. p. 59. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7.

- ↑ Rylands, A. B. (1993). Marmosets and Tamarins: Systematics, Behaviour, and Ecology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854022-1.

- ↑ Emmons, L. H. (1997). Neotropical Rainforest Animals. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-20719-6.

- ↑ Hershkovitz, P. (1977). Living New World Monkeys (Platyrrhini). Vol. 1. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32788-4.

- ↑ Groves, C. (2001). Primate Taxonomy. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-872-X.

- ↑ Mittermeier, Russell A.; Rylands, Anthony B. (1 September 2021). "New primates described from 1 January 1990 to 1 September 2021". IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ↑ Garbino, G. S. T. (2014). "The taxonomic status of Mico marcai (Alperin 1993) and Mico manicorensis (van Roosmalen et al. 2000) (Cebidae, Callitrichinae) from southwestern Brazilian Amazonia". International Journal of Primatology. 35 (2): 529–546. doi:10.1007/s10764-014-9766-4. ISSN 1573-8604. S2CID 18578794.

- ↑ da Silva, F.; Mittermeier, R. A. & Bicca-Marques, J. (21 February 2021). "Mico marcai". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T39914A166609473. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-1.RLTS.T39914A166609473.en.