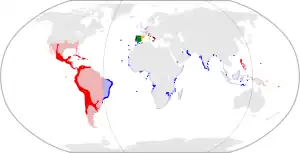

The Spanish Golden Age (Spanish: Siglo de Oro [ˈsiɣlo ðe ˈoɾo], "Golden Century") was a period of flourishing in arts and literature in Spain, coinciding with the political rise of the Spanish Empire under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain and the Spanish Habsburgs. The greatest patron of Spanish art and culture during this period was King Philip II (1556–1598), whose royal palace, El Escorial, invited the attention of some of Europe's greatest architects and painters, such as El Greco, who infused Spanish art with foreign styles and helped create a uniquely Spanish style of painting. The period is associated with the reigns of Isabella I, Ferdinand II, Charles V, Philip II, Philip III, and Philip IV, when Spain was at the peak of its power and influence in Europe and the world.

The start of the Golden Age can be placed in 1492, with the end of the Reconquista, the voyages of Christopher Columbus to the New World, and the publication of Antonio de Nebrija's Grammar of the Castilian Language. It came to an end around the time of the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659)[1] that concluded the Franco-Spanish War of 1635 to 1659. Some extend the Golden Age up to 1681 with the death of Pedro Calderón de la Barca, the last great writer of the age. It can be divided into a Plateresque/Renaissance period and the early part of the Spanish Baroque period.

The period covered the work of Miguel de Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote de la Mancha and Spain's most prolific playwright, Lope de Vega, who wrote around a thousand plays during his lifetime, of which over four hundred survive to the present day. Diego Velázquez, regarded as one of the most influential painters of European history and a greatly respected artist in his own time, was patronised by King Philip IV and his chief minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares.

Some of Spain's greatest music is regarded as having been written in the period. Composers such as Tomás Luis de Victoria, Cristóbal de Morales, Francisco Guerrero, Luis de Milán and Alonso Lobo helped to shape Renaissance music and the styles of counterpoint and polychoral music. Their influence lasted far into the Baroque period, resulting in a revolution of music.

Painting

Spain, in the time of the Italian Renaissance, had seen few great artists come to its shores. The Italian holdings and relationships made by Queen Isabella's husband and later Spain's sole monarch, Ferdinand of Aragon, launched steady traffic of intellectuals across the Mediterranean between Valencia, Seville, and Florence. Luis de Morales, one of the leading exponents of Spanish Mannerist painting, retained a distinctly Spanish style in his work, reminiscent of medieval art. Spanish art, particularly that of Morales, contained a strong mark of mysticism and religion that was encouraged by the counter-reformation and the patronage of Spain's strongly Catholic monarchs and aristocracy. Spanish rule of Naples was important for making connections between Italian and Spanish art, with many Spanish administrators bringing Italian works back to Spain.

El Greco

Known for his unique expressionistic style that was met with both puzzlement and admiration, El Greco (which means "The Greek") was not Spanish, having been born in Crete. He studied the great Italian masters of his time—Titian, Tintoretto, and Michelangelo—when he lived in Italy from 1568 to 1577. According to legend, he asserted that he would paint a mural that would be as good as one of Michelangelo's, if one of the Italian artist's murals was demolished first. El Greco quickly fell out of favor in Italy, but soon found a new home in the city of Toledo, in central Spain. He was influential in creating a style based on impressions and emotion, featuring elongated fingers and vibrant color and brushwork. Uniquely, his works featured faces that captured expressions of somber attitudes and withdrawal, while still having his subjects bear witness to the terrestrial world.[2] His paintings of the city of Toledo became models for a new European tradition in landscapes, and influenced the work of later Dutch masters. Spain at this time was an ideal environment for the Venetian-trained painter. Art was flourishing in the empire and Toledo was a great place to get commissions.

Diego Velázquez

Diego Velázquez was born on June 6, 1599, in Seville. Both parents were from minor nobility. He was the oldest of six children. Velázquez is widely regarded as one of Spain's most important and influential artists. He was a court painter for King Philip IV and found an increasingly high demand for his portraits from statesmen, aristocrats, and clergymen across Europe. His portraits of the King, his chief minister, the Count-duke of Olivares, and the Pope himself demonstrated a belief in artistic realism and a style comparable to many of the Dutch masters. In the wake of the Thirty Years' War, Velázquez met the Marqués de Spinola and painted his famous Surrender of Breda (1635), celebrating Spinola's victory at Breda in 1625. Spinola was struck by his ability to express emotion through realism in both his portraits and landscapes; his work in the latter, in which he launched one of European art's first experiments in outdoor lighting, became another lasting influence on Western painting. Velázquez's friendship with Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, a leading Spanish painter of the next generation, ensured the enduring influence of his artistic approach.

Velázquez's most famous painting is the celebrated Las Meninas, in which the artist includes himself as one of the subjects.

Francisco de Zurbarán

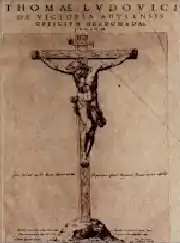

The religious element in Spanish art, in many circles, grew in importance with the counter-reformation. The austere, ascetic, and severe work of Francisco de Zurbarán exemplified this thread in Spanish art, along with the work of composer Tomás Luis de Victoria. Philip IV actively patronized artists who agreed with his views on the counter-reformation and religion. The mysticism of Zurbarán's work—influenced by Saint Theresa of Avila—became a hallmark of Spanish art in later generations. Influenced by Michelangelo da Caravaggio and the Italian masters, Zurbarán devoted himself to an artistic expression of religion and faith. His paintings of St. Francis of Assisi, the immaculate conception, and the crucifixion of Christ reflected a third facet of Spanish culture in the seventeenth century, against the backdrop of religious war across Europe. Zurbarán broke from Velázquez's sharp realist interpretation of art and looked, to some extent, to the emotive content of El Greco and the earlier mannerist painters for inspiration and technique, though Zurbarán respected and maintained the lighting and physical nuance of Velázquez.

It is unknown whether Zurbarán had the opportunity to copy the paintings of Caravaggio; at any rate, he adopted Caravaggio's realistic use of chiaroscuro. The painter who may have had the greatest influence on his characteristically severe compositions was Juan Sánchez Cotán.[3] Polychrome sculpture—which by the time of Zurbarán's apprenticeship had reached a level of sophistication in Seville that surpassed that of the local painters—provided another important stylistic model for the young artist; the work of Juan Martínez Montañés is especially close to Zurbarán's in spirit.

He painted directly from nature, and he made great use of the lay-figure in the study of draperies, in which he was particularly proficient. He had a special gift for white draperies; as a consequence, the houses of the white-robed Carthusians are abundant in his paintings. To these rigid methods, Zurbarán is said to have adhered throughout his career, which was prosperous, wholly confined to Spain, and varied by few incidents beyond those of his daily labour. His subjects were mostly severe and ascetic religious vigils, the spirit chastising the flesh into subjection, the compositions often reduced to a single figure. The style is more reserved and chastened than Caravaggio's, the tone of color often quite bluish. Exceptional effects are attained by the precisely finished foregrounds, massed out largely in light and shade.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo began his art studies under Juan del Castillo in Seville. Murillo became familiar with Flemish painting; the great commercial importance of Seville at the time ensured that he was also subject to influences from other regions. His first works were influenced by Zurbarán, Jusepe de Ribera and Alonso Cano, and he shared their strongly realist approach. As his painting developed, his more important works evolved towards the polished style that suited the bourgeois and aristocratic tastes of the time, demonstrated especially in his Roman Catholic religious works.

In 1642, at the age of 26 he moved to Madrid, where he most likely became familiar with the work of Velázquez, and would have seen the work of Venetian and Flemish masters in the royal collections; the rich colors and softly modeled forms of his subsequent work suggest these influences.[4] He returned to Seville in 1645. That year, he painted thirteen canvases for the monastery of St. Francisco el Grande in Seville, which boosted his reputation. Following the completion of a pair of pictures for the Seville Cathedral, he began to specialize in the themes that brought him his greatest successes, Mary and child Jesus, and the Immaculate Conception.

After another period in Madrid, from 1658 to 1660, he returned to Seville, where he died. Here he was one of the founders of the Academia de Bellas Artes (Academy of Fine Arts), sharing its direction, in 1660, with the architect, Francisco Herrera the Younger. This was his period of greatest activity, and he received numerous important commissions, among them the altarpieces for the Augustinian monastery, and the paintings for Santa María la Blanca (completed in 1665).

Other significant painters

Sculpture

Sculptors of the Renaissance

Sculptors of the Early Baroque period

Architecture

Palace of Charles V

The Palace of Charles V is a Renacentist construction, located on the top of the hill of the Assabica, inside the Nasrid fortification of the Alhambra. It was commanded by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, who wished to establish his residence close to the Alhambra palaces. Although the Catholic Monarchs had already altered some rooms of the Alhambra after the conquest of the city in 1492, Charles V intended to construct a permanent residence befitting an emperor. The project was given to Pedro Machuca, an architect whose biography and influences are poorly understood. Even if accounts that place Machuca in the atelier of Michelangelo are accepted, at the time of the construction of the palace in 1527 the latter had yet to design the majority of his architectural works. At the time, Spanish architecture was immersed in the Plateresque style, still with traces of Gothic origin. Machuca built a palace corresponding stylistically to Mannerism, a mode still in its infancy in Italy.

El Escorial

El Escorial is a historical residence of the king of Spain. It is one of the Spanish royal sites and functions as a monastery, royal palace, museum, and school. It is located about 45 kilometres (28 mi) northwest of the Spanish capital, Madrid, in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial. El Escorial comprises two architectural complexes of great historical and cultural significance: El Real Monasterio de El Escorial itself and La Granjilla de La Fresneda, a royal hunting lodge and monastic retreat about five kilometers away. These sites have a dual nature; that is to say, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they were places in which the temporal power of the Spanish monarchy and the ecclesiastical predominance of the Roman Catholic religion in Spain found a common architectural manifestation. El Escorial was, at once, a monastery and a Spanish royal palace. Originally a property of the Hieronymite monks, it is now a monastery of the Order of Saint Augustine.

Philip II of Spain, reacting to the Protestant Reformation sweeping through Europe during the sixteenth century, devoted much of his lengthy reign (1556–1598) and much of his seemingly inexhaustible supply of New World silver to stemming the Protestant tide sweeping through Europe, while simultaneously fighting the Islamic Ottoman Empire. His protracted efforts were, in the long run, partly successful. However, the same counter-reformational impulse had a much more benign expression, thirty years earlier, in Philip's decision to build the complex at El Escorial.

Philip engaged the Spanish architect, Juan Bautista de Toledo, to be his collaborator in the design of El Escorial. Juan Bautista had spent the greater part of his career in Rome, where he had worked on the basilica of St. Peter's, and in Naples, where he had served the king's viceroy, whose recommendation brought him to the king's attention. Philip appointed him architect-royal in 1559, and together they designed El Escorial as a monument to Spain's role as a center of the Christian world.

Plaza Mayor in Madrid

The Plaza Mayor in Madrid, built during the Habsburg period, is a central plaza in the city of Madrid, Spain. It is located only a few blocks away from another famous plaza, the Puerta del Sol. The Plaza Mayor is rectangular in shape, measuring 129 by 94 meters, and is surrounded by three-story residential buildings having 237 balconies facing the Plaza. It has a total of nine entranceways. The Casa de la Panadería, serving municipal and cultural functions, dominates the Plaza Mayor.

The origins of the Plaza go back to 1589 when Philip II of Spain asked Juan de Herrera, a renowned Renaissance architect, to discuss a plan to remodel the busy and chaotic area of the old Plaza del Arrabal. Juan de Herrera was the architect who designed the first project in 1581 to remodel the old Plaza del Arrabal but construction did not start until 1617, during Philip III's reign. The king asked Juan Gómez de Mora to continue with the project, and he finished the porticoes in 1619. Nevertheless, the Plaza Mayor as we know it today is the work of the architect Juan de Villanueva who was entrusted with its reconstruction in 1790 after a spate of big fires. Giambologna's equestrian statue of Philip III dates to 1616, but it was not placed in the center of the square until 1848.

Granada Cathedral

Unlike most cathedrals in Spain, construction of this cathedral had to await the acquisition of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada from its Muslim rulers in 1492; while its very early plans had Gothic designs, such as are evident in the Royal Chapel of Granada by Enrique Egas, the construction of the church in the main occurred at a time when Renaissance designs were supplanting the Gothic regnant in Spanish architecture of prior centuries. Foundations for the church were laid by the architect Egas starting from 1518 to 1523 atop the site of the city's main mosque; by 1529, Egas was replaced by Diego de Siloé who labored for nearly four decades on the structure from ground to cornice, planning the triforium and five naves instead of the usual three. Most unusually, he created a circular capilla mayor rather than a semicircular apse, perhaps inspired by Italian ideas for circular 'perfect buildings' (e.g. in Alberti's works). Within its structure the cathedral combines other orders of architecture. It took 181 years for the cathedral to be built.

Subsequent architects included Juan de Maena (1563–1571), followed by Juan de Orea (1571–1590), and Ambrosio de Vico (1590-?). In 1667 Alonso Cano, working with Gaspar de la Peña, altered the initial plan for the main façade, introducing Baroque elements. The magnificence of the building would be even greater, if the two large 81-meter towers foreseen in the plans had been built; however the project remained incomplete for various reasons, among them, financial.

Granada Cathedral had been intended to become the royal mausoleum for Charles I of Spain, but Philip II of Spain moved the site for his father and subsequent kings to El Escorial outside of Madrid.

The main chapel contains two kneeling effigies of the Catholic King and Queen, Ferdinand and Isabel, by Pedro de Mena y Medrano. The busts of Adam and Eve were made by Alonso Cano. The Chapel of the Trinity has a marvelous retablo with paintings by El Greco, Alonso Cano, and José de Ribera (The Spagnoletto).

Cathedral of Valladolid

The Cathedral of Valladolid, like all the buildings of the late Spanish Renaissance built by Herrera and his followers, is known for its purist and sober decoration, its style being the typical Spanish clasicismo, also called "Herrerian". Using classical and renaissance decorative motifs, Herrerian buildings are characterized by their extremely sober decorations, its formal austerity, and its like for monumentality.

The cathedral has its origins in a late gothic Collegiate which started during the late 15th century. Before becoming capital of Spain, Valladolid was not a bishopry, and thus lacked the right of building a cathedral. Soon enough though, the Collegiate became obsolete due to the changes of preference during the period, and thanks to the newly established episcopal in the city, the Town Council decided to build a cathedral that would share similar architecture to neighboring capitals.

Had the building been finished, it would have been one of the biggest cathedrals in Spain. When the building was started, Valladolid was the de facto capital of Spain, housing king Philip II and his court. However, due to strategic and geopolitical reasons, by the 1560s the capital was moved to Madrid, making Valladolid lose its political and economic relevance. By the late sixteenth century, Valladolid's importance had been severely reduced, and many of the monumental projects such as the cathedral, started during its prosperous years, had to be modified due to the lack of proper finance. Thus, the building that stands now could not be finished completely, and due to several additions built during the 17th and 18th centuries, lacks the purported stylistical uniformity sought by Herrera. Although mainly faithful to the project of Juan de Herrera, the building would undergo many modifications.

Significant architects

Renaissance and Plateresque period

Early Baroque period

- Domingo Antonio de Andrade

- Eufrasio López de Rojas

- Juan Gómez de Mora

Music

Tomás Luis de Victoria

Tomás Luis de Victoria, a Spanish composer of the sixteenth century, mainly of choral music, is widely regarded as one of the greatest Spanish classical composers. He joined the cause of Ignatius of Loyola in the fight against the Reformation and in 1575 became a priest. He lived for a short time in Italy, where he became acquainted with the polyphonic work of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina. Like Zurbarán, Victoria mixed the technical qualities of Italian art with the religion and culture of his native Spain. He invigorated his work with emotional appeal, experimental mystical rhythm and choruses. He broke from the dominant tendency among his contemporaries by avoiding complex counterpoint, preferring longer, simpler, less technical and more mysterious melodies, employing dissonance in ways that the Italian members of the Roman School shunned. He demonstrated considerable invention in musical thought by connecting the tone and emotion of his music to those of his lyrics, particularly in his motets. Like Velázquez, Victoria was employed by the monarch – in Victoria's case, in the service of the queen. The Requiem he wrote upon her death in 1603 is regarded as one of his most enduring and complex works.

Francisco Guerrero

Francisco Guerrero, a Spanish composer of the 16th century. He was second only to Victoria as a major Spanish composer of church music in the second half of the 16th century. Of all the Spanish Renaissance composers, he was the one who lived and worked the most in Spain. Others, e.g. Morales and Victoria, spent large portions of their careers in Italy. Guerrero's music was both religious and secular, unlike that of Victoria and Morales, the two other Spanish 16th-century composers of the first rank. He wrote numerous secular songs and instrumental pieces, in addition to masses, motets, and Passions. He was able to capture an astonishing variety of moods in his music, from elation to despair, longing, depression, and devotion; his music remained popular for hundreds of years, especially in cathedrals in Latin America. Stylistically he preferred homophonic textures, rather than Spanish contemporaries. One feature of his style is how he anticipated functional harmonic usage: there is a case of a Magnificat discovered in Lima, Peru, once thought to be an anonymous 18th century work, which turned out to be a work of his.

Alonso Lobo

Victoria's work was complemented by Alonso Lobo – a man Victoria respected as his equal. Lobo's work – also choral and religious in its content – stressed the austere, minimalist nature of religious music. Lobo sought out a medium between the emotional intensity of Victoria and the technical ability of Palestrina; the solution he found became the foundation of the Baroque musical style in Spain.

Cristóbal de Morales

Regarded as one of the finest composers in Europe around the middle of the 16th century,[5] Cristóbal de Morales was born in Seville in 1500 and employed in Rome from 1535 until 1545 by the Vatican. Almost all of his music is religious, and all of it is vocal, though instruments may have been used in an accompanying role in performance. Morales also wrote two masses on the famous L'homme armé melody, which was often set by composers in the late 15th and 16th centuries. One of these masses is for four voices, and the other for five. The four voice mass uses the tune as a strict cantus firmus, and the setting for five voices treats it more freely, migrating it from one voice to another.[6]

Other significant musicians

Literature

_El_ingenioso_hidalgo_Don_Quixote_de_la_Mancha.png.webp)

The Spanish Golden Age was a time of great flourishing in poetry, prose and drama.

Cervantes and Don Quixote

Regarded by many as one of the finest works in any language, El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes was the first novel published in Europe; it gave Cervantes a stature in the Spanish-speaking world comparable to his contemporary William Shakespeare in English. The novel, like Spain itself, was caught between the Middle Ages and the modern world. A veteran of the Battle of Lepanto (1571), Cervantes had fallen on hard times in the late 1590s and was imprisoned for debt in 1597, and some believe that during these years he began work on his best-remembered novel. The first part of the novel was published in 1605; the second in 1615, a year before the author's death. Don Quixote resembled both the medieval, chivalric romances of an earlier time and the novels of the early modern world. It parodied classical morality and chivalry, found comedy in knighthood, and criticized social structures and the perceived madness of Spain's rigid society. The work has endured to the present day as a landmark in world literary history, and it was an international hit in its own time, interpreted variously as a satirical comedy, social commentary and forebear of self-referential literature.

Lope de Vega and Spanish drama

A contemporary of Cervantes, Lope de Vega consolidated the essential genres and structures which would characterize the Spanish commercial drama, also known as the "Comedia", throughout the 17th century. While Lope de Vega wrote prose and poetry as well, he is best remembered for his plays, particularly those grounded in Spanish history. Like Cervantes, Lope de Vega served with the Spanish army and was fascinated with the Spanish nobility. In the hundreds of plays he wrote, with settings ranging from the Biblical times to legendary Spanish history to classical mythology to his own time, Lope de Vega frequently took a comical approach just as Cervantes did, taking a conventional moral play and dressing it up in good humor and cynicism. His stated goal was to entertain the public, much as Cervantes's was. In bringing morality, comedy, drama, and popular wit together, Lope de Vega is often compared to his English contemporary Shakespeare. Some have argued that as a social critic, Lope de Vega attacked, like Cervantes, many of the ancient institutions of his country – aristocracy, chivalry, and rigid morality, among others. Lope de Vega and Cervantes represented an alternative artistic perspective to the religious asceticism of Francisco Zurbarán. Lope de Vega's "cloak-and-sword" plays, which mingled intrigue, romance, and comedy together were carried on by his literary successor, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, in the later seventeenth century.

Poetry

This period also produced some of the most important Spanish works of poetry. The introduction and influence of Italian Renaissance verse is apparent perhaps most vividly in the works of Garcilaso de la Vega and illustrate a profound influence on later poets. Mystical literature in Spanish reached its summit with the works of San Juan de la Cruz and Teresa of Ávila. Baroque poetry was dominated by the contrasting styles of Francisco de Quevedo and Luis de Góngora; both had a lasting influence on subsequent writers, and even on the Spanish language itself.[7] Lope de Vega was a gifted poet of his own, and there were a vast quantity of remarkable poets at that time, though less known: Francisco de Rioja, Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola, Lupercio Leonardo de Argensola, Bernardino de Rebolledo, Rodrigo Caro, and Andrés Rey de Artieda. Another poet was Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, from the Spanish colonies overseas, the New Spain ( modern day Mexico).

The picaresque genre flourished in this era, describing the life of pícaros, living by their wits in a decadent society. Distinguished examples are El buscón, by Francisco de Quevedo, Guzmán de Alfarache by Mateo Alemán, Estebanillo González and the anonymously published Lazarillo de Tormes (1554), which created the genre.

Other significant authors

- Juana Inés de la Cruz was a Mexican writer, philosopher, composer, poet of the Baroque period, and Hieronymite nun. She wrote poetry and prose dealing with such topics as love, feminism, and religion.[8] In addition to the two comedies ; Pawns of a House (Los empeños de una casa) and Love is but a Labyrinth (Amor es mas laberinto), Sor Juana is attributed as the author of a possible ending to the comedy by Agustin de Salazar: The Second Celestina (La Segunda Celestina).[9]

- Alonso de Ercilla wrote the epic poem La Araucana about the Spanish conquest of Chile.

- Gil Vicente was Portuguese, but his influence on Spanish playwriting was so wide that he is often considered part of the Spanish Golden Era.

- Francisco de Avellaneda was a prolific writer of short comedies and dances.

Other well-known playwrights of the period include:

Rhetoric

As elsewhere in Europe, Spanish scholars participated in the humanist recovery and theorizing of Greek and Roman rhetorics. Early Spanish humanists include Antonio Nebrija and Juan Luis Vives.[10] Spanish rhetoricians who discussed Ciceronianism include Juan Lorenzo Palmireno and Pedro Juan Núñez.[10] Famous Spanish Ramists include Francisco Sánchez de Brozas, Pedro Juan Núñez, Fadrique Furió Ceriol, and Luis de Verga.[10] Many other rhetoricians turned to Greek rhetorics from Hermogenes and Longinus which were preserved by Byzantine scholars, especially George of Trebizond.[10] These Byzantine-inspired Spanish rhetoricians include Antonio Lull, Pedro Juan Núñez, and Luis de Granada.[10] There were also many translators of progymnasmata, including Francisco de Vergara, Francisco Escobar, Juan de Mal Lara, Juan Pérez, Antionio Lull, Juan Lorenzo Palmireno, and Pedro Juan Núñez.[10] Another important Spanish rhetorician is Cypriano Soarez, whose rhetorical handbook was a key textbook in the Jesuit Ratio studiorum which was used in Jesuit education throughout the Spanish empire.[11] Diego de Válades's Rhetorica christiana is the first Western rhetoric published by a native of México.[12] Besides Soarez's De arte rhetorica, the progymnasmata by Pedro Juan Núñez was also published in Mexico City.[11] Examples of Nahua oratory (huehuetlatolli) were collected by Andrés de Olmos and Bernardino de Sahagún.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ "Siglo de Oro en España".

- ↑ Elliott, J. H. (1963). Imperial Spain: 1469–1716. Penguin Books, p. 385.

- ↑ Gudiol, José; Gállego, Julián (1987). Zurbaran 1598–1664. London, UK: Alpine Fine Arts Collection. p. 15.

- ↑ "Esteban-Murillo Bartolome Esteban Murillo". Britannica online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 30 September 2007.]

- ↑ Stevenson, Robert; Alejandro Planchart: Cristóbal Morales, Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy. Retrieved 9 November 2006. (subscription access) Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Gangwere, Blanche (2004). Music History During the Renaissance Period, 1520–1550. Westport, Connecticut, Praeger Publishers, pp. 216–219.

- ↑ Alonso, Dámaso (1950). La lengua poética de Góngora. Madrid: Revista de Filología Española, p. 112.

- ↑ "Sor Juana Ines de La Cruz, famous women of Mexico". Mexonline.com. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ↑ Kirk Rappaport, Pamela (1998). Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0826410436.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 López-Grigera, Luisa (1983). "An Introduction to the Study of Rhetoric in 16th Century Spain". Dispositio. 8 (22/23): 1–18. JSTOR 41491633.

- 1 2 Osorio Romero, Ignacio (1983). "La retórica en Nueva España". Dispositio. 8 (22/23): 65–86. ISSN 0734-0591. JSTOR 41491636.

- ↑ Abbott, Don Paul (1996). Rhetoric in the New World : rhetorical theory and practice in colonial Spanish America. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-085-5. OCLC 33334281.

- ↑ Abbott, Don P. (1987-08-01). "The Ancient Word: Rhetoric in Aztec Culture". Rhetorica. 5 (3): 251–264. doi:10.1525/rh.1987.5.3.251. ISSN 0734-8584.

- Writers of the Spanish Golden Age, Literature, EDSITEment Lesson Plan of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, Sor Juana, The Poet: The Sonnets Archived 2011-04-08 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Domínguez Ortiz, Antonio (1971). The Golden Age of Spain, 1516-1659. New York: Basic Books Inc.

- Domínguez Ortiz, A., Gállego, J., & Pérez Sánchez, A. E. (1989). Velázquez . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780810939066.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Friedman, Edward H. and Catherine Larson, eds. (1999). Brave New Words: Studies in Spanish Golden Age Literature.

- Kamen, Henry (2005). Golden Age Spain (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-3337-9.

- Stoichita, Victor, ed. (1997). Visionary Experience in the Golden Age of Spanish Art.

- Thomas, Hugh (2010). The Golden Age: The Spanish Empire of Charles V.

- Weller, Thomas (2011). The "Spanish Century", European History Online, Mainz: Institute of European History.

External links

- Digitized collection of Spanish Golden Theatre at Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional de España (National Library of Spain)

- Text search on (untranscribed) images of the BNE Digitized collection of Spanish Golden Theatre.

- Scholarly articles about the Spanish Old Masters and the Spanish golden Age at Spanish Old Masters Gallery