| History of Laos | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Muang city-states era | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Lan Xang era | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Regional kingdoms era | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Colonial era | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Independent era | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| See also | ||||||||||||||

Evidence of modern human presence in the northern and central highlands of Indochina, which constitute the territories of the modern Laotian nation-state, dates back to the Lower Paleolithic.[1] These earliest human migrants are Australo-Melanesians—associated with the Hoabinhian culture—and have populated the highlands and the interior, less accessible regions of Laos and all of Southeast Asia to this day. The subsequent Austroasiatic and Austronesian marine migration waves affected landlocked Laos only marginally, and direct Chinese and Indian cultural contact had a greater impact on the country.[2][3]

Laos exists in truncated form from the thirteenth-century Lao kingdom of Lan Xang, which existed as a unified kingdom from 1357 to 1707, divided into the three rival kingdoms of Luang Prabang, Vientiane, and Champasak, from 1707 to 1779. It fell to Siamese suzerainty from 1779 to 1893 and was reunified under the French Protectorate of Laos in 1893. The borders of the modern state of Laos were established by the French colonial government in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[4][5][6] The modern nation-state of Laos emerged from the French Colonial Empire as an independent country in 1953.

Limitations and current state of research

Archaeological exploration in Laos has been limited due to rugged and remote topography, a history of twentieth century conflicts which have left over two million tons of unexploded ordnance throughout the country, and local sensitivities to history which involve the Communist government of Laos, village authorities and rural poverty. The first archaeological explorations of Laos began with French explorers acting under the auspices of the École française d'Extrême-Orient. However, due to the Lao Civil War it is only since the 1990s that serious archaeological efforts have begun in Laos. Since 2005, one such effort, The Middle Mekong Archaeological Project (MMAP) has excavated and surveyed numerous sites along the Mekong and its tributaries around Luang Prabang in northern Laos, with the goal of investigating early human settlement of the valleys of the Mekong River and its tributaries.

Prehistory

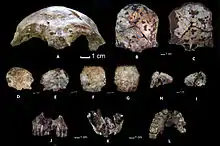

Anatomically modern human hunter-gatherer migration into Southeast Asia before 50,000 years ago has been confirmed by the fossil record of the region.[7] These immigrants might have, to a certain extent, merged and reproduced with members of the archaic population of Homo erectus, as the 2009 fossil discoveries in the Tam Pa Ling Cave suggest. Dated to between 46,000 and 63,000 years old, it is the oldest fossil found in the region that bears modern human morphological features.[8] Recent research also supports more accurate understanding of migration patterns of early humans, who migrated in successive waves moving west to east following the coastlines, but also used river valleys further inland and further north than previously theorized.[9]

An early tradition is discernible in the Hoabinhian, the name given to an industry and cultural continuity of stone tools and flaked cobble artifacts that appears around 10,000 BP in caves and rock shelters first described in Hòa Bình, Vietnam and later also in Laos.[10][11]

Neolithic migrations

The earliest inhabitants of Laos—Australo-Melanesians—were followed by members of the Austro-Asiatic language family. These earliest societies contributed to the ancestral gene pool of the upland Lao ethnicities known collectively as "Lao Theung," with the largest ethnic groups being the Khamu of northern Laos, and the Brao and Katang in the south.[12]

Subsequent Neolithic immigration waves are considered dynamic, very complex and are intensely debated. Researchers resort to linguistic terms and argumentation for group identification and classification.[12]

Agriculture and bronze production

Wet-rice and millet farming techniques were introduced from the Yangtze River valley in southern China since around 2,000 years BC. Hunting and gathering remained an important aspect of food provision; particularly in forested and mountainous inland areas.[13] Earliest known copper and bronze production in Southeast Asia has been confirmed at the site of Ban Chiang in modern north-east Thailand and among the Phung Nguyen culture of northern Vietnam since around 2000 BCE.[14]

Plain of Jars

From the 8th century BCE to as late as the 2nd century CE, an inland trading society emerged on the Xieng Khouang Plateau, around the megalithic site called the Plain of Jars. The plain, nominated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992, is still being cleared from unexploded ordnance, since 1998. The jars, stone sarcophagi dating from the early Iron Age (500 BCE to 800 CE), contained evidence of human remains, burial goods, and ceramics. Some sites contain more than 250 individual jars. The tallest jars are more than 3 m (9.8 ft) in height. Little is known about the culture that produced and used them. The jars and the existence of iron ore in the region suggest that the creators of the site engaged in profitable overland trade.[15][16]

Early Indianised kingdoms

Funan kingdom

The first indigenous kingdom to emerge in Indochina was referred to in Chinese histories as the Kingdom of Funan and encompassed an area of modern Cambodia, and the coasts of southern Vietnam and southern Thailand since the 1st century CE. Funan was an Indianised kingdom, that had incorporated central aspects of Indian institutions, religion, statecraft, administration, culture, epigraphy, writing and architecture and engaged in profitable Indian Ocean trade.[18][19]

Champa kingdom

By the 2nd century CE, Austronesian settlers had established an Indianised kingdom known as Champa along modern central Vietnam. The Cham people established the first settlements near modern Champasak in Laos. Funan expanded and incorporated the Champasak region by the sixth century CE, when it was replaced by its successor polity Chenla. Chenla occupied large areas of modern-day Laos as it accounts for the earliest kingdom on Laotian soil.[19][20]

Chenla kingdom

The capital of early Chenla was Shrestapura which was located in the vicinity of Champasak and the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Wat Phu. Wat Phu is a vast temple complex in southern Laos which combined natural surroundings with ornate sandstone structures, which were maintained and embellished by the Chenla peoples until 900 CE, and were subsequently rediscovered and embellished by the Khmer in the 10th century.

By the 8th century CE, Chenla had divided into "Land Chenla" located in Laos, and "Water Chenla" founded by Mahendravarman near Sambor Prei Kuk in Cambodia. Land Chenla was known to the Chinese as "Po Lou" or "Wen Dan" and dispatched a trade mission to the Tang dynasty court in 717 CE. Water Chenla, would come under repeated attack from Champa, the Mataram sea kingdoms in Indonesia based in Java, and finally pirates. From the instability the Khmer emerged.[21]

Dvaravati city-state kingdoms

In the area that is modern northern and central Laos and northeast Thailand, the Mon people established their own kingdoms during the 8th century CE, outside the reach of the contracting Chenla kingdoms. By the 6th century in the Chao Phraya River Valley, Mon peoples had coalesced to create the Dvaravati kingdoms. In the north, Haripunjaya (Lamphun) emerged as a rival power to the Dvaravati. By the 8th century the Mon had pushed north to create city states, known as "muang," in Fa Daet (northeast Thailand), Sri Gotapura (Sikhottabong) near modern Tha Khek, Laos, Muang Sua (Luang Prabang), and Chantaburi (Vientiane). In the 8th century CE, Sri Gotapura (Sikhottabong) was the strongest of these early city states, and controlled trade throughout the middle Mekong region. The city states were loosely bound politically, but were culturally similar and introduced Therevada Buddhism from Sri Lankan missionaries throughout the region.[15][16]

Tai migrations

There have been many theories proposing the origin of the Tai peoples—of which the Lao are a subgroup—including an association of the Tai people with the Kingdom of Nanzhao that has been proven to be invalid.[24] The Chinese Han dynasty chronicles of the southern military campaigns provide the first written accounts of Tai–Kadai speaking peoples who inhabited the areas of modern Yunnan China and Guangxi.

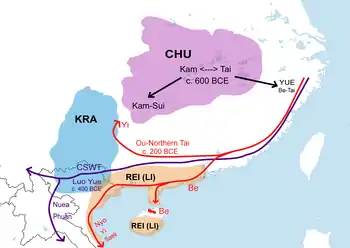

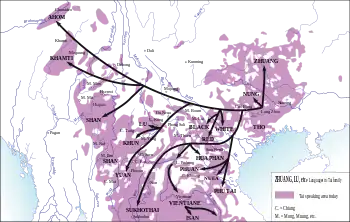

James R. Chamberlain (2016) proposes that Tai-Kadai (Kra-Dai) language family was formed as early as the 12th century BCE in the middle Yangtze basin, coinciding roughly with the establishment of the Chu and the beginning of the Zhou dynasty.[25] Following the southward migrations of Kra and Hlai (Rei/Li) peoples around the 8th century BCE, the Be-Tai people started to break away to the east coast in the present-day Zhejiang, in the 6th century BCE, forming the state of Yue.[25] After the destruction of the state of Yue by Chu army around 333 BCE, Yue people (Be-Tai) began to migrate southwards along the east coast of China to what are now Guangxi, Guizhou and northern Vietnam, forming Luo Yue (Central-Southwestern Tai) and Xi Ou (Northern Tai).[25] The Tai peoples, from Guangxi and northern Vietnam began moving south—and westwards in the first millennium CE, eventually spreading across the whole of mainland Southeast Asia.[26] Based on layers of Chinese loanwords in proto-Southwestern Tai and other historical evidence, Pittayawat Pittayaporn (2014) proposes that the southwestward migration of Tai-speaking tribes from the modern Guangxi and northern Vietnam to the mainland of Southeast Asia must have taken place sometime between the 8th and 10th centuries.[2] Tai speaking tribes migrated southwestward along the rivers and over the lower passes into Southeast Asia, perhaps prompted by the Chinese expansion and suppression. Chinese historical texts record that, in 722, 400,000 'Lao'[lower-alpha 1] rose in revolt behind a leader who declared himself the king of Nanyue in Guangdong.[27][28] After the 722 revolt, some 60,000 were beheaded.[27] In 726, after the suppression of a rebellion by a 'Lao' leader in the present-day Guangxi, over 30,000 rebels were captured and beheaded.[28] In 756, another revolt attracted 200,000 followers and lasted four years.[29] In the 860s, many local people in what is now north Vietnam sided with attackers from Nanchao, and in the aftermath some 30,000 of them were beheaded.[29][30] In the 1040s, a powerful matriarch-shamaness by the name of A Nong, her chiefly husband, and their son, Nong Zhigao, raised a revolt, took Nanning, besieged Guangzhou for fifty seven days, and slew the commanders of five Chinese armies sent against them before they were defeated, and many of their leaders were killed.[29] As a result of these three bloody centuries, the Tai began to migrate southwestward.[29] A 2016 mitochondrial genome mapping of Thai and Lao populations supports the idea that both ethnicities originate from the Tai–Kadai (TK) language family.[31]

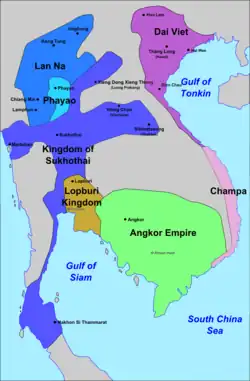

The Tai, from their new home in Southeast Asia, were influenced by the Khmer and the Mon and most importantly Buddhist India. The Tai kingdom of Lanna was founded in 1259 (in the north of modern Thailand). The Sukhothai Kingdom was founded in 1279 (in modern Thailand) and expanded eastward to take the city of Chantaburi and renamed it to Vieng Chan Vieng Kham (modern Vientiane) and northward to the city of Muang Sua which was taken in 1271 and renamed the city to Xieng Dong Xieng Thong or "City of Flame Trees beside the River Dong", (modern Luang Prabang, Laos). The Tai peoples had firmly established control in areas to the northeast of the declining Khmer Empire. Following the death of the Sukhothai king Ram Khamhaeng, and internal disputes within the kingdom of Lanna, both Vieng Chan Vieng Kham (Vientiane) and Xieng Dong Xieng Thong (Luang Prabang) were independent city-states until the founding of the kingdom of Lan Xang in 1354.[15][16][32] The Sukhothai Kingdom and later the Ayutthaya kingdom were established and "...conquered the Khmers of the upper and central Menam valley and greatly extended their territory."[33]

The Legend of Khun Borom

The history of the Tai migrations into Laos were preserved in myth and legends. The Nithan Khun Borom or "Story of Khun Borom" recalls the origin myths of the Lao, and follows the exploits of his seven sons to found the Tai kingdoms of Southeast Asia. The myths also recorded the laws of Khun Borom, which set the basis of common law and identity among the Lao. Among the Khamu the exploits of their folk hero Thao Hung are recounted in the Thao Hung Thao Cheuang epic, which dramatizes the struggles of the indigenous peoples with the influx of Tai during the migration period. In later centuries the Lao themselves would preserve the legend in written form, becoming one of the great literary treasures of Laos and one of the few depictions of life in Southeast Asia prior to Therevada Buddhism and Tai cultural influence.[15][16]

Lan Xang (1353–1707)

Lan Xang (1353–1707) was one of the largest kingdoms in Southeast Asia. Also known as the "Land of a million elephants under the white parasol" the kingdom's name alludes to the power of the kingship and formidable war machine of the early kingdom. The founding of Lan Xang was recorded in 1353, after a series of conquests by Fa Ngum. From 1353 to 1560 the capital of Lan Xang was Luang Prabang (known alternately as Muang Sua and Xieng Dong Xieng Thong). Under successive kings the kingdom expanded its sphere of influence over an area that now incorporates all of modern Laos, the Sipsong Chu Tai of Vietnam, Sipsong Panna of Southern China, Khorat Plateau region of Thailand, and the Stung Treng region of Northern Cambodia.

Lan Xang existed as a sovereign kingdom for over 350 years. The first serious foreign invasion came from the Dai Viet in 1479, which was defeated, though leaving the capital of Luang Prabang largely destroyed. The first half of the sixteenth century allowed for the power, prestige and cultural influence of the kingdom to be restored under a series of strong kings (see Souvanna Balang, Vixun, Photisarath). In the 1540s a series of succession disputes in the neighboring Kingdom of Lanna, created a regional rivalry between Burma, Ayutthaya and Lan Xang. In 1540, Lan Xang defeated an incursion from Ayutthaya. By 1545 the Kingdom of Lanna was attacked by the Burmese and then Ayutthaya. Lan Xang entered into an alliance with Lanna, and aided in the defense of the kingdom. In 1547, the kingdoms of Lan Xang and Lanna were briefly unified under Photisarath of Lan Xang and his son Setthathirath in Lanna. Setthathirath would go on to become the king of Lan Xang on the death of his father, and become one of the greatest kings of Lan Xang.

The Burmese Toungoo dynasty began a series of expansions during the late 1550s which culminated under King Bayinnaung. Setthathirath moved the capital of Lan Xang from Luang Prabang to Vientiane in 1560, to better defend against the threat of Burma and to more ably administer the central and southern provinces. Bayinnaung subjugated the Kingdom of Lanna and went on to destroy the kingdom and city of Ayutthaya in 1564. King Setthathirath fought two successful guerilla campaigns against the Burmese invasions, leaving Lan Xang the only independent Tai kingdom until his death in 1572, while on campaign against the Khmer. The Burmese succeeded with the third invasion of Lan Xang around 1573, and Lan Xang became a vassal state until 1591 when the son of Setthathirath, Nokeo Koumane, was able to successfully reassert independence.

Lan Xang recovered and reached the apex of its political and economic power during the seventeenth century under King Sourigna Vongsa, who became the longest reigning of Lan Xang's monarchs (1637–1694) after defeating four rival claimants to the throne. Foreign relations was managed successfully during his reign and the king was known as a firm and just ruler. In the 1640s the first European explorers to leave a detailed account of the kingdom arrived looking to establish trade and secure Christian converts, both were ultimately largely unsuccessful. However, these European visitors reported on the capital's (Vientiane) prosperity and imposing religious buildings. King Sourigna Vongsa was known to uphold the law stricty, an episode exemplified this when he did not intervene when his son (and successor) was sentenced to death when it was found that he seduced the wife of a senior court official. Upon the death of Sourigna Vongsa a succession dispute as well as exploitation by both Ayutthaya and Dai Viet, led to the kingdom of Lan Xang being ultimately divided into constituent kingdoms in 1707.[15][16][34]

Regional kingdoms (1707–1779)

.png.webp)

Beginning in 1707 the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang was partitioned into regional kingdoms of Vientiane, Luang Prabang and later Champasak (1713). The Kingdom of Vientiane was the strongest of the three, with Vientiane extending influence across the Khorat Plateau (now part of modern Thailand) and conflicting with the Kingdom of Luang Prabang for control of the Xieng Khouang Plateau (on the border of modern Vietnam).

The Kingdom of Luang Prabang was the first of the regional kingdoms to emerge in 1707, when King Xai Ong Hue of Lan Xang was challenged by Kingkitsarat, the grandson of Sourigna Vongsa. Xai Ong Hue and his family had sought asylum in Vietnam when they were exiled during the reign of Sourigna Vongsa. Xai Ong Hue gained the support of the Vietnamese Emperor Le Duy Hiep in exchange for recognition of Vietnamese suzerainty over Lan Xang. At the head of a Vietnamese army Xai Ong Hue attacked Vientiane and executed King Nantharat another claimant to the throne. In response Sourigna Vongsa's grandson Kingkitsarat rebelled and moved with his own army from the Sipsong Panna toward Luang Prabang. Kingkitsarat then moved south to challenge Xai Ong Hue in Vientiane. Xai Ong Hue then turned toward the Kingdom of Ayutthaya for support, and an army was dispatched which rather than supporting Xai Ong Hue arbitrated the division between Luang Prabang and Vientiane.

In 1713, the southern Lao nobility continued the rebellion against Xai Ong Hue under Nokasad, a nephew of Sourigna Vongsa, and the Kingdom of Champasak emerged. The Kingdom of Champasak comprised the area south of the Xe Bang River as far as Stung Treng together with the areas of the lower Mun and Chi rivers on the Khorat Plateau. Although less populous than either Luang Prabang or Vientiane, Champasak occupied an important position for regional power and international trade via the Mekong River.

Throughout the 1760s and 1770s the kingdoms of Siam and Burma competed against each other in a bitter armed rivalry, and sought out alliances with the Lao kingdoms to strengthen their relative positions by adding to their own forces and denying them to their enemy. As a result, the use of competing alliances would further militarize the conflict between the northerly Lao kingdoms of Luang Prabang and Vientiane. Between the two major Lao kingdoms if an alliance with one was sought by either Burma or Siam, the other would tend to support the remaining side. The network of alliances shifted with the political and military landscape throughout the latter half of the eighteenth century.[15][16]

Siam and suzerainty (1779–1893)

By 1779, General Taksin had driven the Burmese from Siam, had overrun the Lao Kingdoms of Champasak and Vientiane, and forced Luang Prabang to accept vassalage (Luang Prabang had aided Siam during the siege of Vientiane). Traditional power relationships in Southeast Asia followed the Mandala model, warfare was waged to secure population centers for corvee labor, control regional trade, and confirm religious and secular authority by controlling potent Buddhist symbols (white elephants, important stupas, temples, and Buddha images). To legitimize the Thonburi dynasty, General Taksin seized the Emerald Buddha and Phra Bang images from Vientiane. Taksin also demanded that the ruling elites of the Lao kingdoms and their royal families pledge vassalage to Siam in order to retain their regional autonomy in accordance with the Mandala model. In the traditional Mandala model, vassal kings retained their power to raise tax, discipline their own vassals, inflict capital punishment, and appoint their own officials. Only matters of war, and succession required approval from the suzerain. Vassals were also expected to provide annual tribute of gold and silver (traditionally modeled into trees), provide tax and tax in-kind, raise support armies in time of war, and provide corvee labor for state projects.

However, by 1782 Taksin had been deposed and Rama I was king of Siam, and began a series of reforms which fundamentally altered the traditional Mandala. Many of the reforms took place to more closely administer and assimilate the Khorat Plateau (or Isan) which was traditionally and culturally part of the Lao kingdoms’ tributary networks. In 1778, only Nakhon Ratchasima was a tributary of Siam, yet by the end of the reign of Rama I Sisaket, Ubon, Roi Et, Yasothon, Khon Khaen, and Kalasin paid tribute directly to Bangkok. According to Thai records, by 1826 (less than fifty years) the number of towns and cities in Isan had grown from 13 to 35. Forced population transfers from Lao areas were further reinforced by corvee labor projects and increased taxes. Siam required labor to help rebuild from repeated Burmese invasions, and growing sea trade. Increasing the productivity and population living on the Khorat Plateau provided the labor and material access to strengthen Siam.

Siribunnyasan the last independent king of Vientiane had died by 1780, and his sons Nanthasen, Inthavong, and Anouvong had been taken to Bangkok as prisoners during the sack of Vientiane in 1779. The sons would become successive kings of Vientiane (under Siamese suzerainty), beginning with Nanthasen in 1781. Nanthasen was allowed to return to Vientiane with the Phra Bang, the palladium of Lan Xang, the Emerald Buddha remained in Bangkok and became an important symbol to the Lao of their captivity. One of Nanthasen's first acts was to seize Chao Somphu a Phuan prince from Xieng Khouang who had entered into a tributary relationship with Vietnam, and released him only when it was agreed that Xieng Khouang would also acknowledge Vientiane as suzerain. In 1791, Anuruttha was confirmed by Rama I as king of Luang Prabang. By 1792 Nanthasen had convinced Rama I that Anuruttha was secretly dealing with the Burmese, and Siam allowed Nanthasen to lead an army and besiege and capture Luang Prabang. Anuruttha was sent to Bangkok as a prisoner, and only through diplomatic exchanges facilitated by China, was Anuruttha released in 1795. Soon after Anuruttha's release it was alleged that Nanthasen had been plotting with the governor of Nakhon Phanom to rebel against Siam. Rama I ordered the immediate arrest of Nanthasen, and soon after he died in captivity. Inthavong (1795–1804) became the next king of Vientiane, and dispatched armies to aide Siam against Burmese invasions in 1797 and 1802, and to capture the Sipsong Chau Tai (with his brother Anouvong as general).[15][16]

Anouvong's and Lao nationalism

Anouvong is a symbolic and controversial figure even today, his short lived rebellion against Siam from 1826 to 1829 ultimately proved futile and led to the total annihilation of Vientiane as a kingdom and a city, yet among the Lao he remains a potent symbol of unyielding defiance and national identity. Thai and Vietnamese histories record that Anouvong rebelled as the result of personal insult suffered at the funeral of Rama II in Bangkok. Yet, the Anouvong's rebellion lasted three years and engulfed the whole of the Khorat Plateau for more complex reasons.

The history of forced population transfers, corvee labor projects, loss of national symbols and prestige (most notably the Emerald Buddha) formed the backdrop to specific actions taken by Rama III to directly annex the Isan region. In 1812, Siam and Vietnam were at odds over the succession of the Cambodian king, the Vietnamese gained the upper hand with their chosen successor and Siam compensated itself by annexing territory on the Dangrek Mountains and along the Mekong River in Stung Treng. As a result, Lao international trade along the Mekong was effectively blockaded, and heavy duties were imposed on Lao merchants who were viewed suspiciously by Siam for their trade with both the Cambodians and Vietnamese.

In 1819, a rebellion in Champasak provided Anouvong with opportunity, and he dispatched an army under his son Nyo who managed to suppress the conflict. In exchange Anouvong successfully made the case that his son be crowned as king in Champasak, which was confirmed by Bangkok. Anouvong had successfully expanded his influence throughout Vientiane, Isan, Xieng Khouang and now Champasak. Anouvong dispatched a number of diplomatic missions to Luang Prabang, which were viewed suspiciously in light of his growing regional influence.

By 1825 Rama II had died, and Rama III was consolidating his position against prince Mongkut (Rama IV). In the ensuing power struggle before the accession of Rama III one of Anouvong's grandsons was killed. When Anouvong arrived for the funerary services, he made several requests of the king Rama III which were dismissed including the return of his sister who had been captured in 1779, and Lao families which had been relocated to Saraburi near Bangkok. Before returning to Vientiane, Anouvong's son Ngau, the crown prince, was forced to perform manual labor during which he was beaten.

Early in his reign, Rama III ordered a census of all peoples on the Khorat Plateau, the census involved the forced tattooing of each villager's census number and name of their village. The aim of the policy was to more tightly administer Lao territories from Bangkok and was facilitated by the nobility Siam had installed in the newly created cities throughout the region. Popular resentment against the forced tattooing and increased taxes became casus belli for rebellion.

Toward the end of 1826 Anouvong was making military preparations for armed rebellion. Anouvong's strategy involved three objectives, first was to repatriate all ethnic Lao living in Siam to the right bank of the Mekong and execute any Siamese engaged in the tattooing of Lao, the second objective was to consolidate Lao power by forging an alliance with Chiang Mai and Luang Prabang, the third and final goal was to gain international support from either the Vietnamese, Chinese, Burmese or British. In January hostilities commenced, and the Lao armies were sent from Vientiane to capture Nakhon Ratchasima, Kalasin, and Lomsak. From Champasak forces rushed to take Ubon and Suvannaphum, while pursuing a scorched-earth policy ensuring the Lao time to retreat.

Anouvong's forces pushed south eventually to Saraburi to free the Lao there, but the flood of refugees pushing north slowed the armies’ retreat. Anouvong also severely underestimated the Siamese arms stockpile, which under the terms of Burney Treaty had provided Siam with weaponry from the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. A Lao defense was staged at Nong Bua Lamphu the traditional Lao stronghold in the Isan, but the Siamese emerged victorious and leveled the city. The Siamese pushed north to take Vientiane and Anouvong fled southeast to the border with Vietnam. By 1828 Anouvong had been captured, tortured and sent to Bangkok with his family to die in a cage. Rama III ordered Chao Bodin to return and level the city of Vientiane, and forcibly move the entire population of the former Lao capital to the Isan region.[15][16]

Aftermath and Vietnamese intervention

Following the Anouvong's rebellion Siam and Vietnam were increasingly at odds over control of the Indochinese Peninsula. In 1831, Emperor Minh Mang sent Vietnamese troops to seize Xieng Khouang and annexed the area as the province of Tran Ninh. Also in 1831 and again in 1833 King Mantha Tourath sent a tributary mission to the Vietnamese, which were quietly ignored so as not to antagonize the Siamese further. In 1893, these tributary missions from Luang Prabang were used by the French as part of a legal argument for all the territories on the east bank of the Mekong. In late 1831 Siam and Vietnam had a series of wars (Siamese-Vietnamese War 1831–1834, and Siamese-Vietnamese War 1841–1845) over control of Xieng Khouang and Cambodia.

In the aftermath of Vientiane's destruction the Siamese divided the Lao lands into three administrative regions. In the north, the king of Luang Prabang and a small Siamese garrison controlled Luang Prabang, the Sipsong Panna, and Sipsong Chao Tai. The central region was administered from Nong Khai and extended to the borders of Tran Ninh (Xieng Khouang) and south to Champasak. The southern regions were controlled from Champasak and extended to areas bordering Cochin China and Cambodia. From the 1830s through the 1860s small rebellions took place across Lao lands and the Khorat Plateau, but they lacked both the scale and coordination of the Anouvong Rebellion. Importantly, at the end of each rebellion Siamese troops would return to their administrative centers, and no Lao region was allowed to have a buildup of force which could have been used in rebellion.[15][16]

Population transfers and slavery

.jpg.webp)

Population transfers of ethnic Lao to Siam began in 1779 with Siamese suzerainty. Artisans and members of the court were forcibly moved to Saraburi near Bangkok, and several thousand farmers and peasant who were transported throughout Siam to Phetchaburi, Ratchaburi, and Nakhon Chaisi in the southwest and to Prachinburi and Chanthaburi in the southeast. However, massive deportations estimated between 100,000 and 300,000 people began following the defeat of King Anouvong in 1828, and would continue until the 1870s. From 1828 to 1830, over 66,000 people were forcibly relocated from Vientiane. In 1834, the first of several relocations of the Phuan areas of Xieng Khouang began, transferring more than 6,000 people. Most of those relocated were settled in the Isan region and were considered that cha loei or "war slaves" who were to serve as serfs in underpopulated areas for the Thai elite. The result changed the demographics and cultural traditions of Thailand and Laos and continues today with a five-fold disparity between the ethnic Lao living on the West Bank of the Mekong and those left in the East in what is today Laos.

Although slavery existed in Lao areas before the rebellion in 1828, the defeat and subsequent removal of most ethnic Lao left a depopulated and vulnerable position for the remaining people of the East Bank of the Mekong. Lao Theung hill tribes which had little involvement in the 1828 rebellion bore the brunt of organized slave raids into Laos and became known collectively and pejoratively in Thai and Lao as kha or "slaves." Lao Theung were hunted or sold into slavery frequent organized raiding parties from Vietnam, Cambodia, Siam, Laos and China. Larger tribes of Lao Theung, such as the Brao, would conduct slave raids against weaker tribes. The raids continued throughout the remainder of the nineteenth century, a Siamese military campaign in Laos in 1876 was described by a British observer as having been "transformed into slave-hunting raids on a large scale".

The population transfers and slave raids ameliorated toward the end of the nineteenth century when European observers and anti-slavery groups made their presence increasingly difficult for the Bangkok elite. In 1880, both slave raiding and trading became illegal, although debt slavery would persist until 1905 by decree of King Chulalongkorn. The French would use the existence of slavery in Siam as one of the major professed motivations for establishing a Protectorate of Laos during the 1880s and 1890s.[15][16]

Haw Wars

In the 1840s, sporadic rebellions, slave raids, and movement of refugees throughout the areas that would become modern Laos left whole regions politically and militarily weak. In China the Qing dynasty was pushing south to incorporate hill peoples into the central administration, at first floods of refugees and later bands of rebels from the Taiping Rebellion pushed into Lao lands. The rebel groups became known by their banners and included the Yellow (or Striped) Flags, Red Flags and the Black Flags. The bandit groups rampaged throughout the countryside, with little response from Siam.

During the early and mid-nineteenth century the first Lao Sung including the Hmong, Mien, Yao and other Sino-Tibetan groups began settling in the higher elevations of Phongsali province and northeast Laos. The influx of immigration was facilitated by the same political weakness which had given shelter to the Haw bandits and left large depopulated areas throughout Laos.

By the 1860s, the first French explorers were pushing north charting the path of the Mekong River, with hope of a navigable waterway to southern China. Among the early French explorers was an expedition led by Francis Garnier, who was killed during an expedition by Haw rebels in Tonkin. The French would increasingly conduct military campaigns against the Haw in both Laos and Vietnam (Tonkin) until the 1880s.[15][16]

Colonial period

Origins of French colonialism in Laos

French colonial interests in Laos began with the exploratory missions of Doudart de Lagree and Francis Garnier during the 1860s. France hoped to utilize the Mekong River as a route to southern China. Although the Mekong is unnavigable due to a number of rapids, the hope was that the river might be tamed with the help of French engineering and a combination of railways. In 1886, Britain secured the right to appoint a representative in Chiang Mai, in northern Siam. To counter British control in Burma and growing influence in Siam, that same year France sought to establish representation in Luang Prabang, and dispatched Auguste Pavie to secure French interests.

Pavie and French auxiliaries arrived in Luang Prabang in 1887 in time to witness an attack on Luang Prabang by Chinese and Tai bandits who hoped to liberate the brothers of their leader Đèo Văn Trị, who were being held prisoner by the Siamese. Pavie prevented the capture of the ailing King Oun Kham by ferrying him away from the burning city to safety. The incident won the gratitude of the king, provided an opportunity for France to gain control of the Sipsong Chu Thai as part of Tonkin in French Indochina, and demonstrated the weakness of the Siamese in Laos. In 1892, Pavie became Resident Minister in Bangkok, where he encouraged a French policy which first sought to deny or ignore Siamese sovereignty over Lao territories on the east bank of the Mekong, and secondly to suppress the slavery of upland Lao Theung and population transfers of Lao Loum by the Siamese as a prelude to establishing a protectorate in Laos. Siam reacted by denying French trading interests, which by 1893 had increasingly involved military posturing and gunboat diplomacy. France and Siam would position troops to deny each other's interests, resulting in a Siamese siege of Khong Island in the south and a series of attacks on French garrisons in the north. The result was the Paknam Incident of 13 July 1893, the Franco-Siamese War (1893) and the ultimate recognition of French territorial claims in Laos.

.svg.png.webp)

The French were aware that the east-bank territories of the Mekong were "a depopulated, devastated country"—the Siamese forced population transfers following the Anouvong Rebellion had left only a fifth of the original population on the east bank, the majority of Lao Loum and Phuan peoples had been resettled to the areas around the Khorat Plateau. Territorial gains in 1893 were only a springboard to secure French control of the Mekong, to deny Siam as much territorial control as possible by acquiring the Mekong's west-bank territories including the Khorat Plateau, and by negotiating stable borders with British Burma along the former territories which paid tribute to the Kingdom of Luang Prabang. France settled a treaty with China in 1895, gaining control of Luang Namtha and Phongsali. British control of the Shan States and French control of the upper Mekong increased tensions between the colonial rivals. A joint commission completed its work in 1896 and the city of Muang Sing was gained by France; in exchange France recognized Siamese sovereignty over the areas of the Chaophraya River basin. However, the issue of Siamese control over the Khorat Plateau, which was ethnically and historically Lao, was left open for the French, as was Siamese control over the Malay Peninsula which favored British interests. Political events in Europe would shape French Indochinese policy however, and between 1896 and 1904 a new political party took power in Paris which viewed Britain much more as an ally than as a colonial rival. In 1904, Britain and France signed the Entente Cordiale, which developed ultimately into part of the alliance against Germany and Austria-Hungary that fought the First World War in 1914–1918. The Entente Cordiale agreement established respective spheres of influence in Southeast Asia, although French territorial demands would continue until 1907 in Cambodia.

1893–1939

The French Protectorate of Laos established two (and at times three) administrative regions governed from Vietnam in 1893. It was not until 1899 that Laos became centrally administered by a single Resident Superieur based in Savannakhet, and later in Vientiane. The French chose to establish Vientiane as the colonial capital for two reasons, firstly it was more centrally located between the central provinces and Luang Prabang, and secondly the French were aware of the symbolic importance of rebuilding the former capital of the Lan Xang Kingdom which the Siamese had destroyed.

As part of French Indochina both Laos and Cambodia were seen as a source of raw materials and labor for the more important holdings in Vietnam. French colonial presence in Laos was light; the Resident Superieur was responsible for all colonial administration from taxation to justice and public works. The French maintained a military presence in the colonial capital under the Garde Indigene made up of Vietnamese soldiers under a French commander. In important provincial cities like Luang Prabang, Savannakhet, and Pakse there would be an assistant resident, police, paymaster, postmaster, schoolteacher and a doctor. Vietnamese filled most upper level and mid-level positions within the bureaucracy, with Lao being employed as junior clerks, translators, kitchen staff and general laborers. Villages remained under the traditional authority of the local headmen or chao muang. Throughout the colonial administration in Laos the French presence never amounted to more than a few thousand Europeans. The French concentrated on the development of infrastructure, the abolition of slavery and indentured servitude (although corvee labor was still in effect), trade including opium production, and most importantly the collection of taxes.

Under French rule, the Vietnamese were encouraged to migrate to Laos, which was seen by the French colonists as a rational solution to a practical problem within the confines of an Indochina-wide colonial space.[35] By 1943, the Vietnamese population stood at nearly 40,000, forming the majority in the largest cities of Laos and enjoying the right to elect their own leaders.[36] As a result, 53% of the population of Vientiane, 85% of Thakhek and 62% of Pakse were Vietnamese, with only an exception of Luang Phrabang where the population was predominantly Lao.[36] As late as 1945, the French even drew up an ambitious plan to move massive Vietnamese population to three key areas, i.e. the Vientiane Plain, Savannakhet region, Bolaven Plateau, which was only discarded by Japanese invasion of Indochina.[36] Otherwise, according to Martin Stuart-Fox, the Lao might well have lost control over their own country.[36]

The Lao response to French colonialism was mixed, although the French were viewed as preferable to the Siamese by the nobility, the majority of Lao Loum, Lao Theung, and Lao Sung were burdened by regressive taxes and demands for corvee labor to establish colonial outposts. The first serious resistance to the French colonial presence began in southern Laos, as the Holy Man's Rebellion led by Ong Keo, and would last until 1910. The rebellion began in 1901 when a French commissioner in Salavan was attempting to pacify Lao Theung tribes for taxation and corvee labor, Ong Keo provoked anti-French sentiment and in response the French burned a local temple. The commissioner and his troops were massacred and a general uprising began throughout the Bolaven Plateau. Ong Keo would be killed by French forces, but for several years his harassment and protests gained popularity in the southern Laos. It was not until the movement spread to the Khorat Plateau and threatened to become an international incident involving Siam that several French columns of the Garde Indigene converged to put down the rebellion. In the north Tai Lu groups from the areas around Phongsali and Muang Sing also began to rebel against French attempts at taxation and corvee labor.

In 1914, the Tai Lu king had fled to the Chinese portions of the Sipsong Panna, where he began a two-year guerilla campaign against the French in northern Laos, which required three military expeditions to suppress and resulted in direct French control of Muang Sing. In northeast Laos, Chinese and Lao Theung rebelled against French attempts to tax the opium trade which resulted in another rebellion from 1914 to 1917. By 1915 most of northeast Laos was controlled by Chinese and Lao Theung rebels. The French dispatched the largest military presence yet to Laos which included 160 French officers and 2500 Vietnamese troops divided in two columns. The French drove the Chinese led rebels across the Chinese border and placed Phongsali under direct colonial control. Yet northeastern Laos was still not entirely pacified and a Hmong shaman named Pa Chay Vue attempted to establish a Hmong homeland through a rebellion (pejoratively termed the Madman's War) which lasted from 1919 to 1921.

By 1920, the majority of French Laos was at peace and colonial order had been established. In 1928, the first school for the training of Lao civil servants was established, and allowed for the upward mobility of Lao to fill positions occupied by the Vietnamese. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s France attempted to implement Western, particularly French, education, modern healthcare and medicine, and public works with mixed success. The budget for colonial Laos was secondary to Hanoi, and the worldwide Great Depression further restricted funds. It was also in the 1920s and 1930s that the first strings of Lao nationalist identity emerged due to the work of Prince Phetsarath Rattanavongsa and the French Ecole Francaise d’Extreme Orient to restore ancient monuments, temples, and conduct general research into Lao history, literature, art and architecture. French interest in indigenous history served a dual purpose in Laos it reinforced the image of the colonial mission as protection against Siamese domination, and was also a legitimate route for scholarship.[15][16]

World War II

Developing Lao national identity gained importance in 1938 with the rise of the ultranationalist prime minister Phibunsongkhram in Bangkok. Phibunsongkhram renamed Siam to Thailand, a name change which was part of a larger political movement to unify all Tai peoples under the central Thai of Bangkok. The French viewed these developments with alarm, but the Vichy government was diverted by events in Europe and World War II. Despite a non-aggression treaty signed in June 1940, Thailand took advantage of the French position and initiated the Franco-Thai War. The war concluded unfavorably for Lao interests with the Treaty of Tokyo, and the loss of trans-Mekong territories of Xainyaburi and part of Champasak. The result was Lao distrust of the French and the first overtly national cultural movement in Laos, which was in the odd position of having limited French support. Charles Rochet the French Director of Public Education in Vientiane, and Lao intellectuals led by Nyuy Aphai and Katay Don Sasorith began the Movement for National Renovation.

Yet the wider impact of World War II had little effect on Laos until February 1945, when a detachment from the Japanese Imperial Army moved into Xieng Khouang. The Japanese preempted that the Vichy administration of French Indochina under Admiral Decoux would be replaced by a representative of the Free French loyal to Charles DeGaulle and initiated Operation Meigo ("bright moon"). The Japanese succeeded in the internment of the French living in Vietnam and Cambodia, but in the remote areas of Laos the French were able with the help of the Lao and Garde Indigene to establish jungle bases which were supplied by British airdrops from Burma. However, French control in Laos had been sidelined.[16]

Lao Issara and independence

1945 was a watershed year in the history of Laos. Under Japanese pressure, King Sisavangvong declared independence in April. The move allowed the various independence movements in Laos including the Lao Seri and Lao Pen Lao to coalesce into the Lao Issara or "Free Lao" movement which was led by Prince Phetsarath and opposed the return of Laos to the French. The Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945 emboldened pro-French factions and Prince Phetsarath was dismissed by King Sisavangvong. Undeterred Prince Phetsarath staged a coup in September and placed the royal family in Luang Prabang under house arrest. On 12 October 1945 the Lao Issara government was declared under the civil administration of Prince Phetsarath. In the next six months the French rallied against the Lao Issara and were able to reassert control over Indochina in April 1946. The Lao Issara government fled to Thailand, where they maintained opposition to the French until 1949, when the group split over questions regarding relations with the Vietminh and the communist Pathet Lao was formed. With the Lao Issara in exile, in August 1946 France instituted a constitutional monarchy in Laos headed by King Sisavangvong, and Thailand agreed to return territories seized during the Franco-Thai War in exchange for a representation at the United Nations. The Franco-Lao General Convention of 1949 provided most members of the Lao Issara with a negotiated amnesty and sought appeasement by establishing the Kingdom of Laos a quasi-independent constitutional monarchy within the French Union. In 1950, additional powers were granted to the Royal Lao Government including training and assistance for a national army. On 22 October 1953, the Franco–Lao Treaty of Amity and Association transferred remaining French powers to the independent Royal Lao Government. By 1954 the defeat at Dien Bien Phu brought eight years of fighting with the Vietminh, during the First Indochinese War, to an end and France abandoned all claims to the colonies of Indochina.[16]

Kingdom of Laos and the Lao Civil War (1953–1975)

Elections were held in 1955, and the first coalition government, led by Prince Souvanna Phouma, was formed in 1957. The coalition government collapsed in 1958. In 1960, Captain Kong Le staged a coup when the cabinet was away at the royal capital of Luang Prabang and demanded reformation of a neutralist government. The second coalition government, once again led by Souvanna Phouma, was not successful in holding power. Rightist forces under General Phoumi Nosavan drove out the neutralist government from power later that same year. The North Vietnamese invaded Laos between 1958 and 1959 to create the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

A second Geneva conference, held in 1961–62, provided for the independence and neutrality of Laos, but the agreement meant little in reality and the war soon resumed. Growing North Vietnamese military presence in the country increasingly drew Laos into the Second Indochina War (1954–1975). As a result, for nearly a decade, eastern Laos was subjected to some of the heaviest bombing in the history of warfare,[37] as the U.S. sought to destroy the Ho Chi Minh Trail that passed through Laos and defeat the Communist forces. The North Vietnamese also heavily backed the Pathet Lao and repeatedly invaded Laos. The government and army of Laos were backed by the USA during the conflict. The United States trained both regular Royal Lao forces and irregular forces among whom many were the Hmong and other ethnic minorities.

Shortly after the Paris Peace Accords led to the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam, a ceasefire between the Pathet Lao and the government led to a new coalition government. However, North Vietnam never withdrew from Laos and the Pathet Lao remained little more than a proxy army for Vietnamese interests. After the fall of South Vietnam to communist forces in April 1975, the Pathet Lao with the backing of North Vietnam were able to take total power with little resistance. On 2 December 1975, the king was forced to abdicate his throne and the Lao People's Democratic Republic was established. Around 300,000 people out of a total population of three million left Laos by crossing the border into Thailand following the end of the civil war.[38][16]

Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–present)

The new communist government led by Kaysone Phomvihane imposed centralized economic decision-making and incarcerated many members of the previous government and military in "re-education camps" which also included the Hmong. While nominally independent, the communist government was for many years effectively little more than a puppet regime run from Vietnam.

The government's policies prompted about 10 percent of the Lao population to leave the country. Laos depended heavily on Soviet aid channeled through Vietnam up until the Soviet collapse in 1991. In the 1990s the communist party gave up centralised management of the economy but still has a monopoly of political power.[16][39]

Explanatory notes

References

Citations

- ↑ Bellwood, Peter (10 April 2017). First Islanders: Prehistory and Human Migration in Island Southeast Asia (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781119251545.

- 1 2 Pittayaporn, Pittayawat (2014). Layers of Chinese loanwords in Proto-Southwestern Tai as Evidence for the Dating of the Spread of Southwestern Tai Archived 27 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, Special Issue No 20: 47–64.

- ↑ "Origins of Ethnolinguistic Identity in Southeast Asia" (PDF). Roger Blench. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ↑ "Laos Brief History". Asia Web Direct. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ "Laos History". The National Assembly of Laos. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ "Lao People's Democratic Republic History Timeline". Worldatlas Com. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ "Oldest bones from modern humans in Asia discovered". CBSNews. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ↑ Marwick, Ben; Bouasisengpaseuth, Bounheung (2017). "History and Practice of Archaeology in Laos". In Habu, Junko; Lape, Peter; Olsen, John (eds.). Handbook of East and Southeast Asian Archaeology. Springer.

- ↑ Demeter, Fabrice; Shackelford, Laura; Westaway, Kira; Duringer, Philippe; Bacon, Anne-Marie; Ponche, Jean-Luc; Wu, Xiujie; Sayavongkhamdy, Thongsa; Zhao, Jian-Xin; Barnes, Lani; Boyon, Marc; Sichanthongtip, Phonephanh; Sénégas, Frank; Karpoff, Anne-Marie; Patole-Edoumba, Elise; Coppens, Yves; Braga, José; Macchiarelli, Roberto (7 April 2015). "Early Modern Humans and Morphological Variation in Southeast Asia: Fossil Evidence from Tam Pa Ling, Laos". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0121193. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1021193D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121193. PMC 4388508. PMID 25849125.

- ↑ Marwick, B. (2013). "Multiple Optima in Hoabinhian flaked stone artifact palaeoeconomics and palaeoecology at two archaeological sites in Northwest Thailand". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 32 (4): 553–564. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2013.08.004.

- ↑ Ji, Xueping; Kuman, Kathleen; Clarke, R.J.; Forestier, Hubert; Li, Yinghua; Ma, Juan; Qiu, Kaiwei; Li, Hao; Wu, Yun (1 December 2015). "The oldest Hoabinhian technocomplex in Asia (43.5 ka) at Xiaodong rockshelter, Yunnan Province, southwest China". Quaternary International. 400: 166–174. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.09.080. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- 1 2 Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume One, Part One. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66369-4. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ↑ Charles Higham. "Hunter-Gatherers in Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to the Present". Digitalcommons. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ↑ Higham, Charles; Higham, Thomas; Ciarla, Roberto; Douka, Katerina; Kijngam, Amphan; Rispoli, Fiorella (10 December 2011). "The Origins of the Bronze Age of Southeast Asia". Journal of World Prehistory. 24 (4): 227–274. doi:10.1007/s10963-011-9054-6. S2CID 162300712. Retrieved 11 February 2017 – via Researchgate.net.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Maha Sila Viravond. "History of laos" (PDF). Refugee Educators' Network. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 M.L. Manich. "History of Laos (including the history of Lonnathai, Chiangmai)" (PDF). Refugee Educators' Network. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann (2004). A history of India. Rothermund, Dietmar 1933– (4th ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 0203391268. OCLC 57054139.

- ↑ Carter, Alison Kyra (2010). "Trade and Exchange Networks in Iron Age Cambodia: Preliminary Results from a Compositional Analysis of Glass Beads". Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association. 30. doi:10.7152/bippa.v30i0.9966. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- 1 2 Kenneth R. Hal (1985). Maritime Trade and State Development in Early Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8248-0843-3.

- ↑ National Library of Australia. Asia's French Connection : George Coedes and the Coedes Collection Archived 21 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations by Charles F. W. Higham – Chenla – Chinese histories record that a state called Chenla..." (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam", p. 67. In Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 104, 2016.

- ↑ Baker, Chris and Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017). "A History of Ayutthaya", p. 27. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Du Yuting; Chen Lufan (1989). "Did Kublai Khan's Conquest of the Dali Kingdom Give Rise to the Mass Migration of the Thai People to the South?" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. Siam Heritage Trust. JSS Vol. 77.1c (digital). image 7 of p. 39. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

The Thai people in the north as well as in the south did not in any sense "migrate en masse to the south" after Kublai Khan's conquest of the Dali Kingdom.

- 1 2 3 Chamberlain, James R. (2016). "Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam", pp. 27–77. In Journal of the Siam Society, Vol. 104, 2016.

- ↑ Grant Evans. "A Short History of Laos – The land in between" (PDF). Higher Intellect – Content Delivery Network. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- 1 2 Baker 2002, p. 5.

- 1 2 Taylor 1991, p. 193.

- 1 2 3 4 Baker & Phongpaichit 2017, p. 26.

- ↑ Taylor 1991, pp. 239–249.

- ↑ "Complete mitochondrial genomes of Thai and Lao populations indicate an ancient origin of Austroasiatic groups and demic diffusion in the spread of Tai–Kadai languages" (PDF). Max Planck Society. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ↑ "A Short History of South East Asia Chapter 3. The Repercussions of the Mongol Conquest of China ...The result was a mass movement of Thai peoples southwards..." (PDF). Stanford University. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ Briggs, Lawrence Palmer (1948). "Siamese Attacks On Angkor Before 1430". The Far Eastern Quarterly. Association for Asian Studies. 8 (1): 3–33. doi:10.2307/2049480. JSTOR 2049480. S2CID 165680758.

- ↑ Church, Peter (2017). A Short History of South-East Asia (6 ed.). Singapore: Wiley. p. 77.

- ↑ Ivarsson, Søren (2008). Creating Laos: The Making of a Lao Space Between Indochina and Siam, 1860–1945. NIAS Press, p. 102. ISBN 978-8-776-94023-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Stuart-Fox, Martin (1997). A History of Laos. Cambridge University Press, p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-59746-3.

- ↑ Wiseman, Paul (11 December 2003). "30-year-old bombs still very deadly in Laos". Usatoday.Com. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ↑ Courtois, Stephane; et al. (1997). The Black Book of Communism. Harvard University Press. p. 575. ISBN 978-0-674-07608-2.

- ↑ Martin Stuart-Fox. "Politics and Reform in the Lao People's Democratic Republic)" (PDF). University of Queensland. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

Works cited

- Baker, Chris; Phongpaichit, Pasuk (2017), A History of Ayutthaya, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-19076-4

- Baker, Chris (2002), "From Yue To Tai" (PDF), Journal of the Siam Society, 90 (1–2): 1–26

- Taylor, Keith W. (1991), The Birth of Vietnam, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0

Further reading

- Conboy, K. The War in Laos 1960–75 (Osprey, 1989)

- Dommen, A. J. Conflict in Laos (Praeger, 1964)

- Gunn, G. Rebellion in Laos: Peasant and Politics in a Colonial Backwater (Westview, 1990)

- Kremmer, C. Bamboo Palace: Discovering the Lost Dynasty of Laos (HarperCollins, 2003)

- Pholsena, Vatthana. Post-war Laos: The politics of culture, history and identity (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2006).

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. "The French in Laos, 1887–1945." Modern Asian Studies (1995) 29#1 pp: 111–139.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. A history of Laos (Cambridge University Press, 1997)

- Stuart-Fox, M. (ed.). Contemporary Laos (U of Queensland Press, 1982)

External links

- Digital Library of Lao Manuscripts – an online library of historical Lao manuscripts and related background information

- Laos Travel Guide History of Laos

- Andrea Matles Savada, ed. (1994). "Laos: A Country Study". Library of Congress Country Studies. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 8 August 2011.