Patna, the capital of Bihar state, India, is one of the oldest continuously inhabited places in the world and the history of Patna spans at least three millennia. Patna has the distinction of being associated with the two most ancient religions of the world, namely, Buddhism and Jainism. The ancient city of Pataliputra (predecessor of modern Patna) was the capital of the Mauryan, Shunga, and Gupta Empires.

It has been a part of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire and has seen the rule of the Nawabs of Bengal, the East India Company and the British Raj. During British rule, the Patna University, as well as several other educational institutions, were established. Patna was one of the nerve centers of First War of Independence, participated actively in India's Independence movement, and emerged in the post-independent India as the most populous city of East India after Kolkata.

Prehistory and Origin

The first accepted references to the place are observed more than 2500 years ago in Jain and Buddhist scriptures. Recorded history of the city begins in the year 490 BCE when Ajatashatru, the king of Magadha, wanted to shift his capital from the hilly Rajgriha to a more strategically located place to combat the Licchavi of Vaishali. He chose a site on the bank of the Ganges and fortified the area which developed into Patna.

From that time, the city has had a continuous history, a record claimed by few cities in the world. During its history and existence of more than two millennia, Patna has been known by different names: Pataligram, Pataliputra, Palibothra, Kusumpur, Pushpapura, Azimabad, and the present-day Patna. Gautam Buddha passed through this place in the last year of his life, and he had prophesied a great future for this place, but at the same time, he predicted its ruin from flood, fire, and feud.

Etymology

Etymologically, Patna derives its name from the word Pattan, which means port in Sanskrit. It may be indicative of the location of this place on the confluence of four rivers, which functioned as a port. It is also believed that the city derived its name from Patan Devi, the presiding deity of the city, and her temple is one of the shakti peethas.

Patali is the name of the trumpet flower. A very few ascribes the origin of Patna to a mythological king, Putraka, who created Patna by a magic stroke for his queen Patali, literally Trumpet flower, which gives it its ancient name Pataligram. It is said that in honour of the firstborn to the queen, the city was named Pataliputra. Gram is the Sanskrit for a village and Putra means a son.

The Haryankas

According to tradition, the Haryanka dynasty founded in 684 BCE, whose capital was Rajagriha, later Pataliputra, the present-day Patna. This dynasty lasted until 424 BCE when it was overthrown by the Nanda dynasty. This period saw the development of two of India's major religions that started from Magadha. Bimbisara was responsible for expanding the boundaries of his kingdom through matrimonial alliances and conquest. The land of Kosala fell to Magadha in this way. Bimbisara (543-493 BCE ) was imprisoned and killed by his son Ajatashatru (491-461 BCE) who then became his successor, and under whose rule the dynasty reached its largest extent. Ajatashatru went to war with the Licchavi several times. Ajatashatru is thought to have ruled from 491 to 461 BCE and moved his capital of the Magadha kingdom from Rajagriha to Pataliputra. Udayabhadra eventually succeeded his father, Ajatashatru, under him Pataliputra became the largest city in the world.[1]

The Nandas

The Nanda dynasty was established by an illegitimate son of the king Mahanandin of the previous Shishunaga dynasty. Mahapadma Nanda was a man of fabulous wealth known by various epithets like "Ekarat" and "Sarvakshatrantak" (destroyer of all Kshatriya). According to Arthashastra of Chanakya, the Nanda dynasty was of Shudra origin.[2] During the reign of Mahapadma Nanda, Alexander the Great invaded India. The soldiers of Alexander were not in the favour of facing the Magadhan army which included elephants and a large number of foot soldiers besides cavalry and chariots. Hence, they departed without a face-off though they had already ravaged almost entire western India. Mahapadma Nanda died at the age of 88, ruling the bulk of this 100-year dynasty. The next ruler Dhanananda was not popular among his subjects and he is described as cruel in various contemporary works. The Nandas were followed by the Maurya dynasty.[3]

The Mauryas

With the rise of the Mauryan empire (321 BC-185 BCE), Patna, then called Pataliputra became the seat of power and nerve center of the Indian subcontinent. From Pataliputra, the famed emperor Chandragupta ruled a vast empire, stretching from the Bay of Bengal to Afghanistan. Chandragupta established a strong centralized state with a complex administration under the tutelage of Kautilya.[4]

Early Mauryan Pataliputra was mostly built with wooden structures. The wooden buildings and palaces rose to several stories and were surrounded by parks and ponds. Another distinctive feature of the city was the drainage system. Water course from every street drained into a moat which functioned both as defence as well as sewage disposal. According to Megasthenes, Pataliputra of the period of Chandragupta, was "surrounded by a wooden wall pierced by 64 gates and 570 towers— (and) surpassed the splendors of contemporaneous Persian sites such as Susa and Ecbatana".[4]

Chandragupta's son Bindusara deepened the empire towards central and southern India. Patna under the rule of Ashoka, the grandson of Chandragupta, emerged as an effective capital of the Indian subcontinent.

Emperor Ashoka transformed the wooden capital into a stone construction around 273 BCE. Chinese scholar Fa Hein, who visited India sometime around 399-414 CE, has given a vivid description of the stone structures in his travelogue.[4]

According to Pliny the Elder in his "Natural History":

"But the Prasii surpass in power and glory every other people, not only in this quarter, but one may say in all India, their capital Palibothra, a very large and wealthy city, after which some call the people itself the Palibothri,--nay even the whole tract along the Ganges. Their king has in his pay a standing army of 600,000 foot-soldiers, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 elephants: whence may be formed some conjecture as to the vastness of his resources." Plin. Hist. Nat. VI. 21. 8–23. 11.[4]

Learning and scholarship received great state patronage. Pataliputra produced several eminent world-class scholars.

Scholars:

- Aryabhata, the famous astronomer and mathematician who gave the approximation of Pi correct to four decimal places.

- Ashvaghosha, poet and influential Buddhist writer.

- Chanakya, or Kautilya, the master of statecraft, described by Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru as Indian Machiavelli—he was the guru of Chandragupta Maurya and author of the ancient text on statecraft, Arthashashtra.

- Pāṇini, the ancient Hindu grammarian who formulated the 3959 rules of Sanskrit morphology. The Backus–Naur form syntax used to describe modern programming languages have significant similarities to Pāṇini's grammar rules.

- Vatsyayana, the author of Kama Sutra.

It is believed that Pataliputra was the largest city in the world between 300 and 195 BCE, taking that position from Alexandria, Egypt and being succeeded by the Chinese capital Chang'an (modern Xi'an).[5]

The Guptas

Before the Guptas

When the last of the Mauryan kings was assassinated in 184 BCE by Pushyamitra Shunga, India once again became a collection of unfederated kingdoms, though most of the core Magadha territories remained in control of the Shunga Empire who engaged in conflicts with the Indo-Greeks to secure the borders of India. During this period, the most powerful kingdoms were not in the north, but in the Deccan to the south, particularly in the west. The north, however, remained culturally the most active, where Buddhism was spreading and where Hinduism was being gradually remade by the Upanishadic movements, which are discussed in more detail in the section on religious history. The dream, however, of a universal empire had not disappeared. It would be realized by a northern kingdom and would usher in one of the most creative periods in Indian history.[6]

The Gupta Dynasty (240-550)

Under Chandragupta I (320-335), the empire was revived in the north. Like Chandragupta Maurya, he first conquered Magadha, set up his capital where the Mauryan capital had stood (Patna), and from this base consolidated a kingdom over the eastern portion of northern India. In addition, Chandragupta revived many of Ashoka's principles of government. It was his son, however, Samudragupta (335-376), and later his grandson, Chandragupta II (376-415), who extended the kingdom into an empire over the whole of the north and the western Deccan. Chandragupta II was the greatest of the Gupta kings; called Vikramaditya ("The Sun of Power"), he presided over the greatest cultural age in Classical India.[1]

.jpg.webp)

This period is regarded as the golden age of Indian culture. The high points of this cultural creativity are magnificent and creative architecture, sculpture, and painting. The wall-paintings of Ajanta Cave in the central Deccan are considered among the greatest and most powerful works of Indian art. The paintings in the cave represent the various lives of the Buddha, but also are the best source we have of the daily life in India at the time. There are forty-eight caves making up Ajanta, most of which were carved out of the rock between 460 and 480, and they are filled with Buddhist sculptures. The rock temple at Elephanta (near Bombay) contains a powerful, eighteen-foot statue of the three-headed Shiva, one of the principal Hindu gods. Each head represents one of Shiva's roles: that of creating, that of preserving, and that of destroying. The period also saw dynamic building of Hindu temples. All of these temples contain a hall and a tower.[1]

The greatest writer of the time was Kalidasa. Poetry in the Gupta age tended towards a few genres: religious and meditative poetry, lyric poetry, narrative histories (the most popular of the secular works of literature), and drama. Kalidasa excelled at lyric poetry, but he is best known for his dramas. We have three of his plays; all of them are suffused with epic heroism, with comedy, and with erotics. The plays all involve misunderstanding and conflict, but they all end with unity, order, and resolution.[1]

The Guptas tended to allow kings to remain as vassal kings; unlike the Mauryas, they did not consolidate every kingdom into a single administrative unit. This would be the model for later Mughal rule and British rule built on the Mughal paradigm.

The Guptas soon faced a wave of migrations by the Huns, a people who originally lived north of China. The Hun migrations would push all the way to the doors of Rome. Beginning in the 400's, the Huns began to put pressure on the Guptas. They were initially defeated by Skandagupta. However, by 480 they conquered large parts of Northwestern India. Western India was overrun by 500, and the last of the Gupta kings, presiding over a vastly diminished kingdom, perished in 550. However, the Huns were soon defeated by Yasovarman and later Baladitya, scion of the Guptas. A strange thing happened to the Huns in India as well as in Europe. Over the decades they gradually assimilated into the indigenous population and their state weakened.[1]

Harsha, who was a successor of the Guptas, quickly moved to reestablish an Indian empire. From 606 to 647, he ruled over an empire in northern India. Harsha was perhaps one of the greatest conquerors of Indian history, and unlike all of his conquering predecessors, he was a brilliant administrator. He was also a great patron of culture. His capital city, Kanauj, extended for four or five miles along the Ganges River and was filled with magnificent buildings. Only one-fourth of the taxes he collected went to administration of the government. The remainder went to charity, rewards, and especially to culture: art, literature, music, and religion[1]

Because of extensive trade, the culture of India became the dominant culture around the Bay of Bengal, profoundly and deeply influencing the cultures of Burma, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka. In many ways, the period during and following the Gupta dynasty was the period of "Greater India", a period of cultural activity in India and surrounding countries building on the base of Indian culture. This medieval flowering of Indian culture would radically change course in the Indian Middle Ages. From the north came Muslim conquerors out of Afghanistan, and the age of Muslim rule began in 1100.[1]

The Sultanate

With the disintegration of the Gupta empire and continuous invasions of the Indian subcontinent by foreign armies of Hunas, Patna passed through uncertain times like most of north India.

The territory came under the resurgent Empires of Shri Harshavardhana Samrat who extended his control over the entire North-West of India destroying the Hunas, taking the title of "Uttarpatheshwar" i.e. "Lord of the North". However, his advances down South were kept in check by the powerful Chalukya ruler Pulakeshin.

During the Kannauj Triangle struggle period, the region came under the control of the mighty Pala Empire. The legendary king of Kashmir, Lalitaditya Muktapida is said to have passed through the region in his conquering spree.

During the 12th century, the invader Muhammad of Ghor's advancing forces captured Ghazni, Multan, Sindh, Lahore, and Delhi, and one of his generals Qutb-ud-din Aybak proclaimed himself Sultan of Delhi and established the first dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate. By the mid-12th century, Ikhtiar Uddin Muhammad bin Bakhtiar Khilji, one of the generals of Qutb-ud-din Aybak, invaded Bihar and Bengal, and Patna became a part of the Delhi Sultanate. He is said to have destroyed many ancient seats of learning, the most prominent being the Nalanda University near Rajgrih, about 120 km from Patna. Patna, which had already lost its stature as the political centre of India, lost its prestige as the educational and cultural center of India as well.[7]

Foreign invaders often used abandoned viharas and temples as military cantonments. They set up their headquarters in Nalanda region and called it Bihar, which is derived from the term Vihar. The region roughly encompassing the present state of Bihar was dotted with Buddhist vihara, which were the abodes of Buddhist monks in the ancient and medieval period. The town still exists and is called Bihar or Bihar Sharif (Nalanda District). Later on, the headquarters was shifted from Bihar to Patana (current Patna) by Sher Shah Suri and the whole Magadha region was called Bihar.

The Mughals

The Mughal period was a period of unremarkable provincial administration from Delhi. The most remarkable period of these times was under Sher Shah or Sher Shah Suri. Sher Shah Suri hailed from Sasaram, about 160 km south-west of Patna and revived Patna in the middle of the 16th century. On his return from one of the expeditions, while standing by the Ganges, he visualised a fort and a town. Sher Shah's fort in Patna does not survive, but the mosque built by Sher Shah in 1545 survives. It is built in Afghan architectural style. There are numerous tombs inside.

The earliest mosque in Patna is dated 1489 and is built by Alauddin Hussani Shah, one of the Bengal rulers. Local people call it the Begu Hajjam's mosque in honour of a barber who got it repaired in 1646.

Mughal emperor Akbar came to Patna in 1574 to crush the Afghan Chief Daud Khan. Akbar's Secretary of State and author of Ain-i-Akbari refers to Patna as a flourishing centre for paper, stone and glass industries. He also refers to the high quality of numerous strains of rice grown in Patna that is famous as Patna rice in Europe.

In 1610, during the reign of Jahangir, a lower-class uprising occurred in the city led by a man pretending to be Jahangir's son Khusrau Mirza. The rebellious population took control of the town for a week before being defeated and executed by the Mughal army.[8]

The Jagirdar of Mohrampur ruled over the city of Patna. Patna was the most important city in the eastern part of India after Burdwan and served as the capital of Bihar Subah. Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb acceded to the request of his favourite grandson Prince Muhamad Azim to rename Patna as Azimabad, in 1704 while Azim was in Patna as the subedar. However, other than the name, very little changed during this period.

The Nawabs

With the decline of the Mughal empire, Patna moved into the hands of the Nawabs of Bengal, but in time the city was taken over by the Jagirdars who then became the self-declared Nawabs. The Nawabs of Bengal levied a heavy tax on the populace but allowed it to flourish as a commercial centre. During the 17th century, Patna became a centre of international trade.

The British started with a factory in Patna in 1620 for the purchase and storage of calico and silk. Soon it became a trading centre for saltpetre, urging other Europeans—French, Danes, Dutch and Portuguese—to compete in the lucrative business. Various European factories and godowns started mushrooming in Patna and it acquired a trading fame that attracted far off merchants. Peter Mundy, writing in 1632, calls this place, "the greatest mart of the eastern region".

British Colonial period

Company Rule

After the Battle of Buxar, 1764, the Mughals as well as the Nawabs of Bengal lost effective control over the territories then constituting the province of Bengal, which currently comprises the Indian states of West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand, Odisha, as also some parts of Bangladesh. The East India Company was accorded the diwani rights (right to collect revenue), that is, the right to administer the collection and management of revenues of the province of Bengal, and parts of Oudh, currently comprising a large part of Uttar Pradesh. The diwani rights were legally granted by Shah Alam, who was then ruling sovereign Mughal emperor of Undivided India.

The Battle of Buxar, which was fought hardly 115 km from Patna, heralded the establishment of the rule of the British East India Company in East India.

During the rule of the British East India Company in Bihar, Patna emerged as one of the most important commercial and trading centers of East India, preceded only by Kolkata.

British Raj

Under the British Raj, Patna gradually started to attain its lost glory and emerged as an important and strategic centre of learning and trade in India. When the Bengal Presidency was partitioned in 1912 to carve out a separate province, Patna was made the capital of the new province of Bihar and Orissa. The city limits were stretched westwards to accommodate the administrative base, and the township of Bankipore took shape along the Bailey Road (originally spelt as Bayley Road, after the first Lt. Governor, Charles Stuart Bayley). This area was called the New Capital Area.

To this day, locals call the old area as the City whereas the new area is called the New Capital Area. The Patna Secretariat with its imposing clock tower and the Patna High Court are two imposing landmarks of this era of development. Credit for designing the massive and majestic buildings of colonial Patna goes to the architect, J. F. Munnings.[9]

By 1916–1917, most of the buildings were ready for occupation. These buildings reflect either Indo-Saracenic influence (like Patna Museum and the state Assembly), or overt Renaissance influence like the Raj Bhawan and the High Court. Some buildings, like the General Post Office (GPO) and the Old Secretariat, bear pseudo-Renaissance influence. Some say, the experience gained in building the new capital area of Patna proved very useful in building the imperial capital of New Delhi.

The British built several educational institutions in Patna like Patna College, Patna Science College, Bihar College of Engineering, Prince of Wales Medical College and the Patna Veterinary College. With government patronage, the Biharis quickly seized the opportunity to make these centres flourish quickly and attain renown.

After the creation of Orissa as a separate province in 1936, Patna continued as the capital of Bihar province under the British Raj.

Patna played a major role in the Indian independence struggle. Most notable are the Champaran movement against the Indigo plantation and the Quit India Movement of 1942.

Post-Independence

The post Independence period saw the rule of the Indian National Congress party for decades. The leaders associated with Congress in the initial days of independence were Anugrah Narayan Sinha and Sri Krishna Sinha. The freedom fighter image of the early Congress leaders and their popularity among the commoners gave them swift access to power at the cost of the "Politics of social justice", which was to become the feature of Bihari electoral politics in the late 60s. The upper castes of Bihar were the power holders during the early decades under the banner of Congress party and their dominance in local government as well as administration was also evident.[10]

Initially, Kayastha, the most educated class, who had a significant presence in the local administration and government, were the first community to form their own caste organisation. Later other upper castes like Rajputs and Bhumihars also became the new claimants to power, gradually displacing Kayastha from the administration as well as governance. The politics of Backward castes was at ebb during those times and Congress was invincible as a political party.[10]

The growing discontent among backwards with Congress led to the formation of Triveni Sangh political party by the three important backward castes of Bihar. The "Triveni Sangh" was formed not only to act as a power broker for the backward castes but also for ensuring the rights of the lower castes and Dalits. According to Ashwani Kumar, the Dalit women were vulnerable to rapes and assaults particularly by the upper caste Zamindars and "Triveni Sangh" in its manifesto promised to defend their honour.[11] The movement thus worked for reconciliation of lower castes but failed miserably due to competition from superior organisational structure of the Congress's "Backward class federation" and internal disputes between the leaders of the three backward castes who were pivotal in its formation. But, apart from the ballot box, it was successful in eliminating the practices like "Begar".The failure of Sangh also gave rise to Maoism in the rural Bihar and the Ekwaari region, the birthplace of "Triveni Sangh" which became the cockpit of struggle between landed upper castes and the landless lower castes.[11]

The naxal attacks and the eagerness of lower castes to rise up in the socio-economic ladder and the opposition from the upper castes further culminated into the formation of caste-based "private armies" in Bihar. While most of these were formed by upper castes primarily the members of Rajput and Bhumihar caste. Some of the caste armies of new landlords from the backward castes like Kurmi and Yadav also existed. Ranvir Sena, Kuer Sena, Bhumi Sena are some of the notable caste armies.[12]

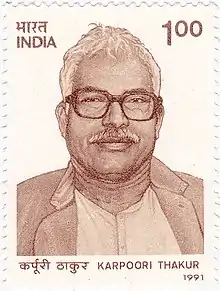

In the sphere of politics the power struggle between upper and lower castes came to end when in 1967 riding on the wave of defining slogan of social justice, castes like Koeri, Kurmi and Yadav replaced the Bhumihars, Rajputs, Brahmins and the Kayastha.[13] During the tenure of Karpoori Thakur, the issues of quota in government jobs were given a boost making it possible for lower castes to break the monopoly of upper castes in administration and pedagogy.[10]

The successors of Karpuri Thakur were weak as in a short period of time a number of Chief Minister came but none of them was able to complete the tenure of 5 years. Until then only Sri Krishna Sinha had remained successful in holding Premiership for a period of more than 5 years.[14] Further caste and communal strife reached a new height during this period. The leaders like Satyendra Narayan Singh, Bindeshwari Dubey and Jagannath Mishra all had their own shortcomings. In the tenure of Satyendra Narayan Singh the infamous Bhagalpur riots took place in which over 900 Muslims were killed while during the tenure of Bindeshwari Dubey, Maoists slaughtered an entire village of Rajputs in which 42 people were killed while others fled.[15][16]

This period saw the rise of a strong leader in Lalu Prasad Yadav. Yadav was a strong critic of upper caste hegemony and was a proponent of the cause of lower castes and Dalits. He took several steps like strict enforcement of the quota system in government jobs and education for the social and economic development of the lower castes. Moreover, Yadav recruited the lower castes into administration and upper castes were sidelined which made them play the secondary role in the politics and administration of Bihar as they were moved to the subordinate position vis a vis the OBCs. The upper caste now turned to violence which was welcomed by the retaliatory action of the backwards. A series of caste-based and politically motivated murders took place during this period.[17][18]

The leaders of the period like Lalu Prasad and Nitish Kumar were born out of the "Bihar movement" of 1977 which was launched by Jay Prakash Narayan.[19] Narayan also launched social justice movement along with Ram Manohar Lohia which is said to have strengthened primarily the "upper backwards". [20] According to Sanjay Kumar:

If any (class/caste) could compete with the upper castes in terms of the social, economic, and political muscle, it was these three upper backward castes—Yadavs, Kurmis, and Koeris. The social coalition of the 1980s was much more politically oiled than the coalition of 1930, during the days of "Triveni Sangh".[20]

Lalu Prasad's was successful in giving voice to marginalized, but the upper caste, who were deliberately sidelined, became his strong critic and a series of violent clashes began in the countryside between upper caste who tried to assume power again and the backwards who were vying for the power and position dominated in the erstwhile period by the upper castes. According to Arun Sinha, the three "upper backward" castes were at the fore in improving their socio-political condition and were putting stiff resistance to the efforts of "upper castes" to dominate once again. But the growing differences between Yadavs with Kurmi and Koeris led Nitish Kumar to form Samata Party. The upper caste also supported Nitish in order to project him as a challenge to the growing dominance of Yadavs and Lalu Prasad.[21][22][23]

Nitish was initially unsuccessful in breaking the effect of Narcissistic personality of Lalu Prasad on the backwards. But he successfully ascended to the power after law and order situation in the tenure of Rabari Devi deteriorated due to multiple factors one of them being tussle between upper and the lower castes. He took energetic steps to contain criminal turned politicians and many of the erstwhile strongmen were put behind the bars. Among those who were booked also included members of his own party.[24]

As of now, the governance of Bihar for the last 15 years (up to 2020) is in the hand of Janata Dal (United) and Bharatiya Janata Party alliance while the Rashtriya Janata Dal of Lalu Prasad is still the biggest party in Bihar Legislative Assembly.[25]

Gallery : Patna as Capital

- Pataliputra as a capital of the Magadha Empire.

Pataliputra as a capital of Maurya Empire.

Pataliputra as a capital of Maurya Empire.

The Maurya Empire at its largest extent under Ashoka the Great. Pataliputra as a capital of Shunga Empire.

Pataliputra as a capital of Shunga Empire.

Approximate greatest extent of the Shunga Empire (c. 185 BCE). Pataliputra as a capital of Sher Shah's Empire.

Pataliputra as a capital of Sher Shah's Empire. Robert Clive became the first British Governor of Bengal, Patna (Bihar) was a part of Bengal.

Robert Clive became the first British Governor of Bengal, Patna (Bihar) was a part of Bengal. First Chief Minister of Bihar, Dr. Sri Krishna Sinha.

First Chief Minister of Bihar, Dr. Sri Krishna Sinha. Lalu Prasad Yadav, longest reigning Chief Minister of Bihar after Srikrishna Sinha.

Lalu Prasad Yadav, longest reigning Chief Minister of Bihar after Srikrishna Sinha..jpg.webp) Nitish Kumar, current Chief Minister of Bihar.

Nitish Kumar, current Chief Minister of Bihar.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 480. ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9.

- ↑ M. B. Chande (1998). Kautilyan Arthasastra. Atlantic Publishers. p. 313. ISBN 978-81-7156-733-1.

During the period of the Nanda Dynasty, the Hindu, Buddha and Jain religions had under their sway the population of the Empire

- ↑ H. C. Raychaudhuri (1988) [1967]. "India in the Age of the Nandas". In K. A. Nilakanta Sastri (ed.). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas (Second ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Chandragupta Maurya and His Times, Radhakumud Mookerji, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1966, p.27 Mookerji, Radhakumud (1966). Chandragupta Maurya and His Times. ISBN 978-81-208-0405-0. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- ↑ "Largest Cities Through History". Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 29 June 2008..

- ↑ Gupta dynasty (Indian dynasty) Archived 30 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ Sarkar, Jadunath, ed. (1973) [First published 1948]. The History of Bengal. Vol. II. Patna: Academica Asiatica. p. 3. OCLC 924890.

Bakhtyār led his army a second time in the direction of Bihar in the year following the sack of the fortified monastery of that name. This year, i.e. 1200 A.D., he was busy consolidating his hold over that province.

- ↑ Wilfred Cantwell Smith (2000). "Lower-class Uprisings in the Mughal Empire". In Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Muzaffar Alam (ed.). The Mughal State, 1526-1750. Oxford University Press. p. 329. ISBN 9780195652253.

- ↑ "British Rule". Glorious Bihar. 26 May 2010. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 Thakur, Baleshwar (2007). City, Society, and Planning: Society. University of Akron. Department of Geography & Planning, Association of American Geographers: Concept Publishing Company. pp. 393–404. ISBN 978-81-8069-460-8. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- 1 2 Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. pp. 43, 44, 196. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

- ↑ "End of a terror trail". frontline.thehindu.com. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ↑ Arnold P. Kaminsky; Roger D. Long (2011). इंडिया टुडे: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic. ABC-CLIO. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-313-37462-3. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Nalin Verma, Laloo Prasad Yadav (2019). Gopalganj to Raisina: My Political Journey. Rupa. ISBN 978-93-5333-313-3. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ "bhagalpur-riots-inquiry-report-blames-congress-police". India Today. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ↑ Ahmed, Farzand. "Massacre-of-42-rajputs-in-bihar-villages-marks-a-new-level-of-brutality". India Today. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ↑ Zarhani, Seyed Hossein (2018). "Elite agency and development in Bihar: confrontation and populism in era of Garibon Ka Masiha". Governance and Development in India: A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after Liberalization. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-25518-9.

- ↑ Gupta, Smita (15 October 2007). "Pinned Lynch". Outlook. PTI. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ↑ Thakur, Sankarshan (2015). The Brothers Bihari. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-93-5177-481-5. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

- 1 2 Kumar, Sanjay (5 June 2018). Post mandal politics in Bihar:Changing electoral patterns. SAGE publication. p. 55. ISBN 978-93-528-0585-3.

- ↑ Sinha, A. (2011). Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Viking. p. 80,81,82,165–169. ISBN 978-0-670-08459-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Shah, Ghanshyam (2004). Caste and Democratic Politics in India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 346, 350–354. ISBN 81-7824-095-5. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ↑ Ahmed, Soroor (18 January 2010). "Upper caste politics at crucial juncture in Bihar". The Bihar Times. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- ↑ Upadhyay, Ashok. "How Nitish Kumar plays the caste card when it suits him". Dailyo.in. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ↑ Zaki Ikbal, Adil Ikram (8 November 2015). "Bihar Assembly Election Results 2015 Live Updates: Grand Alliance bags 180 seats, BJP led NDA 59". India.com. Retrieved 27 August 2020.