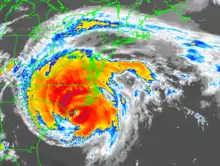

Fran near peak intensity east of Florida on September 4 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 23, 1996 |

| Extratropical | September 8, 1996 |

| Dissipated | September 10, 1996 |

| Category 3 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 120 mph (195 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 946 mbar (hPa); 27.94 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 27 |

| Damage | $5 billion (1996 USD) |

| Areas affected | South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1996 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Fran caused extensive damage in the United States in early September 1996. The sixth named storm, fifth hurricane, and third major hurricane of the 1996 Atlantic hurricane season, Fran developed from a tropical wave near Cape Verde on August 23. Due to nearby Hurricane Edouard, the depression remained disorganized as it tracked westward, though it eventually intensified into Tropical Storm Fran on August 27. While heading west-northwestward, Fran steadily strengthened into a hurricane on August 29, but weakened back to a tropical storm on the following day. On August 31, Fran quickly re-intensified into a hurricane. By September 2, Fran began to parallel the islands of the Bahamas and slowly curved north-northwestward. Early on September 5, Fran peaked as a 120 mph (195 km/h) Category 3 hurricane. Thereafter, Fran weakened slightly, before it made landfall near Cape Fear, North Carolina early on September 6. The storm rapidly weakened inland and was only a tropical depression later that day. Eventually, Fran curved east-northeastward and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over Ontario early on September 9.

In Florida, high tides capsized a boat with five people aboard, though all were rescued. No significant effects were reported in Georgia. The outer bands of Fran produced high winds and light to moderate rainfall in South Carolina. As a result, numerous trees and powerlines were downed, which damaged cars, left over 63,000 people without electricity. Large waves in North Carolina caused significant coastal flooding in some cities. Overall, 27 fatalities and $5 billion (1996 USD) in damage were attributed to Fran. Fran is also the most recent hurricane to make landfall in the Carolinas as a major hurricane.[1][2]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Hurricane Fran originated from a tropical wave that moved off the western coast of Africa, entering the Atlantic Ocean, on August 22, 1996. Not long after moving over water, convective banding features formed around a developing area of low pressure. Ships in the vicinity of the system confirmed that a surface circulation had formed later that day. After further development, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) initiated advisories on the system around 8:00 am EDT on August 23, designating it as Tropical Depression Six. At this time, the depression was situated to the southeast of the Cape Verde Islands. Over the following several days, little development took place as the system moved westward at 17 mph (27 km/h). The westward motion and lack of development were attributed to the low-level inflow from Hurricane Edouard located roughly 850 mi (1,370 km) west-northwest of the depression.[3]

By August 26, the depression had become significantly disorganized, prompting the NHC to issue their initial final advisory on the system.[4] Despite this, the following day, satellite imagery depicted an improved circulation, leading to the re-issuance of advisories.[5] However, post-storm analysis indicated that the system maintained tropical depression status during the 24‑hour span. During the afternoon of August 27, the depression intensified further, becoming a tropical storm and receiving the name Fran. At this time, Tropical Storm Fran was located about 1,000 mi (1,600 km) east of the Lesser Antilles. Following a similar track as Edouard, the newly named storm maintained a west-northwest track while gaining strength.[3]

Following the development of deep convection around Fran's center of circulation on August 29, the NHC upgraded it to a Category 1 hurricane, the lowest ranking on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale, with winds of 75 mph (120 km/h). However, the hurricane weakened to a tropical storm on August 30 as it became less organized, possibly due to an interaction with Hurricane Edouard to the north. During this time, the forward motion of the storm significantly decreased and it took a more northwestward track. However, this weakening was short-lived and Fran re-attained hurricane status the following day as Edouard moved towards the Mid-Atlantic coastline. The storm also resumed its west-northwest movement as a subtropical ridge to the north strengthened.[3]

Gradual reintensification took place for the first several days of September, with Fran attaining winds of 90 mph (145 km/h) on September 3. By this point, the storm began to develop an eye and a more rapid phase of strengthening took place. Early the next day, Fran attained Category 3 intensity as its maximum sustained winds increased to 115 mph (185 km/h). A more northwesterly track also began to appear as it approached the Bahamas. Passing roughly 115 mi (185 km) east of the Bahamas, Fran attained its peak intensity on September 5 with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a barometric pressure of 946 mbar (hPa; 27.94 inHg). The eye of Fran was roughly 29 mi (47 km) in diameter at this time.[3]

As a large hurricane, the storm's forward motion increased as it moved northwest towards The Carolinas. Around 7:30 PM EDT on Thursday, September 5,[6] the center of Hurricane Fran made landfall near Cape Fear, North Carolina with sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). Once overland, the storm began to rapidly weaken, degrading to a tropical storm within 12 hours. As the weakening storm moved through Virginia, the NHC further downgraded it to a tropical depression. Continuing on a northwestern track, the remnants of Fran persisted as a tropical depression through September 8, at which time it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over southern Ontario. After completing this transition, Fran turned northeastward and tracked near the Canadian-United States border before being absorbed by a frontal system on September 10.[3]

Preparations

Lesser Antilles and the Bahamas

| Hurricane warning levels |

|---|

| Hurricane warning |

|

Hurricane conditions expected within 36 hours. |

| Hurricane watch |

|

Hurricane conditions possible within 48 hours. |

| Tropical storm warning |

| Tropical storm conditions expected within 36 hours. |

| Tropical storm watch |

| Tropical storm conditions possible within 48 hours. |

| Storm surge warning |

| Life-threatening storm surge possible within 36 hours. |

| Storm surge watch |

| Life-threatening storm surge possible within 48 hours. |

| Extreme wind warning |

| Winds reaching Category 3 status or higher likely (issued two hours or less before onset of extreme winds). |

As Hurricane Fran passed to the north of the Lesser Antilles on August 29, a hurricane watch was issued for the northernmost of the islands between Antigua and Saint Martin.[7] However, as the hurricane weakened and pulled away from the islands to the northwest, the watch was discontinued. At the same time, a hurricane watch and a tropical storm warning was declared for the central Bahamas. On September 3, the hurricane watch was extended to include the northern Bahamas and a hurricane warning was declared for the northwestern islands. All watches for the Bahamas were cancelled on September 4.[7] No preparations were taken by the government of the Bahamas in anticipation of Fran.[8]

Florida

Early in its span, Hurricane Fran was forecast to heavily impact Florida, and multiple watches and warnings were issued for the state as Hurricane Fran neared the United States.[7] As the hurricane progressively moved further to the north, watches and warnings imposed on Florida continued to move further north along the coast. On September 4, a tropical storm warning was issued, but only from Brunswick, Georgia to Flagler Beach, Florida, located in the northern parts of the state. All watches and warnings on the state were discontinued by September 5.[9]

Before the hurricane neared the coast, civil defense authorities conducted statewide conference calls in order to create preliminary plans in case Fran caused impacts on Florida.[10] In addition, beach patrols were kept on high alert as Fran generated large waves on the Florida beaches.[11]

Georgia

The first hurricane watches and warnings for Georgia were first imposed on September 4 as Hurricane Fran became a major hurricane with a watch extending from Florida through Georgia and into South Carolina[7] The watch was upgraded to a warning later that day as Fran moved closer to the coast. While areas south of Brunswick, Georgia were only issued a tropical storm warning, areas north of the city were declared under a hurricane warning until September 5, when it was downgraded into a tropical storm warning. All watches and warnings on the Georgia coast were discontinued by the end of September 6.

On September 4, while much of Georgia was under a hurricane watch, multiple emergency operation centers were activated. When the watch was upgraded, the state declared a mandatory evacuation for Chatham County while Liberty County issued a voluntary evacuation order for its residents.[7] The state's electric membership corporations began cooperating with other utility companies in preparation for the storm.[12]

Impact

| Region | Fatalities | Damage |

|---|---|---|

| Florida | 0 | None |

| South Carolina | 0 (2) | $48.5 million |

| North Carolina | 13 (1) | >$2.4 billion |

| Virginia | 5 | $350 million |

| Maryland | 0 | $100 million |

| District of Columbia | 0 | $20 million |

| West Virginia | 2 | $40 million |

| Pennsylvania | 2 (2) | $80 million |

| Ohio | 0 | $40 million |

| Total | 22 (5) | ~$5 billion |

Throughout the eastern United States, Fran produced strong winds and heavy rainfall, leading to widespread flash flooding and wind damage. The most severe damage took place in North Carolina where 14 people died, one of which was from a heart attack, and the storm left over $2.4 billion in losses. Throughout other states, 13 other people lost their lives and an additional $800 million in damage was caused. Overall, Hurricane Fran was directly responsible for 22 fatalities and indirectly for five others as well as $5 billion in damage.[13] At the time, Fran was one of the ten costliest hurricanes to strike the United States; however, several other storms have since surpassed it.

Florida and South Carolina

Prior to moving over The Carolinas, large swells produced by Hurricane Fran impacted the Florida coastline. Along the beaches of Palm Beach County, five people aboard an 18 ft (5.5 m) fishing boat were knocked into the water by the rough seas. However, the Coast Guard rescued all five persons without incident.[14]

As Fran made landfall in North Carolina, the outer bands of the storm brought heavy rains and gusty winds to eastern South Carolina. Several areas reported winds in excess of 40 mph (64 km/h), leading to numerous downed trees and power lines. Some cars and homes were damaged after being struck by fallen trees.[15] In Dillon County, winds gusting up to 70 mph (110 km/h) caused significant damage to many homes. Debris was left in the wake of Fran across the county than during Hurricane Hugo in 1989. One person was injured and damage to crops and infrastructure reached $6.5 million.[16] In Marlboro County, roughly 3,200 people were left without power and two sheriffs were injured after their car struck a fallen tree.[17] The most severe damage in South Carolina took place in Horry County where winds reached 77 mph (124 km/h). Numerous trees were felled by the winds, leaving roughly 60,000 residents without power. One person was killed after her car fell down an embankment. Extensive agricultural losses were sustained in the area, estimated at $19.8 million. Structural damage was less severe, with losses estimated at $1 million.[18] A second car-related fatality during Fran took place in Williamsburg County.[19] Combined economic losses in Berkeley and Charleston counties reached $20 million.[20] Throughout South Carolina, Fran was responsible for two fatalities, five injuries and roughly $48.5 million in damage.

North Carolina

Fran caused coastal damage from the South Carolina border to Topsail Island, North Carolina. Its 12-foot storm surge carried away a temporary North Topsail Beach police station and town hall, housed in a double-wide trailer since Hurricane Bertha's rampage across the same area in July. The Kure Beach Pier was destroyed during the storm as well. Extensive flooding struck the coast around Wrightsville Beach, just up the coast from Cape Fear. In Jacksonville, North Carolina, three schools and several homes were damaged. The storm was most damaging to the barrier islands on the North Carolina coastline.

Further inland, the storm caused damage on its way north from Wilmington to Raleigh. Unexpectedly, high wind damage extended along the I-40 corridor up through Raleigh and points north and as far west as Guilford County, damaging historic buildings and trees throughout the Triangle including at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina[21] Classes were canceled for the day at UNC due to a state of emergency in Chapel Hill, and it was almost a week before the university's water supply was drinkable again.

Rain of up to 16 inches (406 mm) deluged interior North Carolina, Virginia and West Virginia,[22] bringing dangerous river flooding to much of the mid-Atlantic. Hurricane Fran's thrashing of North Carolina aggravated the state's problems caused by numerous weather disasters in 1996.

At least six people were killed in the Carolinas; most of them were from automobile accidents and more died as a result of the shock from the damage of the storm. In North Carolina, 1.3 million people were left without power. In North Topsail Beach and Carteret County, there was over $500 million (1996 USD) in damage and 90% of structures were damaged.[23] One male teenager died from drowning caused by flooding of Crabtree Creek at Old Lassiter Mill in Raleigh. Fran also destroyed the basketball gym on the campus of St. Andrews College in Laurinburg, North Carolina as well as 3 piers in Surf City.

Total damage in North Carolina amounted to over $2.4 billion.[24]

This was the second hurricane to make landfall on North Carolina that year. The first was Hurricane Bertha, which hit the state a few weeks prior.[25]

Virginia

In Virginia, tropical storm-force winds lashed Chesapeake Bay and increased water levels in the Potomac River around the nation's capital, where it backed up into Georgetown and Old Town Alexandria, Virginia. There was severe damage to power lines that left 415,000 people without electricity, making it the largest storm related power outage in history until Hurricane Isabel in 2003.[23] Along the Rappahannock River, a storm surge of 5 ft (1.5 m) damaged or sank several small boats and damaged wharfs and bulkheads. This was the highest tide in the state since Hurricane Hazel of 1954.[23]

Rain up to 16 in (410 mm) fell in the western part of Virginia, making Fran the fourth wettest known tropical cyclone to impact Virginia and causing major flash flooding. The floods shut down many of the primary and secondary roads and closed Shenandoah National Park.[26] Fran destroyed about 300 homes, mostly from flooding, and 100 people had to be rescued.

Page County, downslope of the 16" of rainfall from Big Meadows, was the hardest hit locality in the state of Virginia with regards to damage. Three days after the storm had passed, "hundreds" of people were still stranded. Some 78 homes were destroyed and 417 were damaged, however there were no deaths. At one point on Friday every town in the county was isolated due to high water.[27]

.jpg.webp)

In the county seat of Luray, the Hawksbill Creek cut the town in half for much of the day, and the strong current forced a house off its foundation and placed in the endzone of Luray High School's football field. Water from the Hawksbill reached 2 ft (0.61 m) from the top of the field goal upright— 16 ft (4.9 m) of water covered the ground. Bulldog field was flooded for over a week after the storm, until finally the standing water was pumped across U.S. Route 340 back into the Hawksbill Creek. Also in downtown Luray, the large flood-driven waves of the creek demolished three buildings, including the Adelphia Cable building. The creek, typically less than a foot deep, overtook the downtown Main Street Bridge, which rises some 15 ft (4.6 m) above the creek bed.[28]

The Shenandoah River crested some 20 ft (6.1 m) above flood stage. The South Fork of the Shenandoah River recorded its highest crests ever, 26.95 ft (8.21 m) in Luray and 37 ft (11 m) in Front Royal, Virginia, which was 22 ft (6.7 m) above the 15 ft (4.6 m) flood stage.[29]

In Rockingham County, Virginia, over 10,000 people were evacuated from their homes, however most were allowed to return to their homes after the water subsided.[30]

West Virginia

Up to 7 inches (178 mm) of rain fell,[22] causing widespread flash flooding. Pendleton and Hardy County were the hardest hit as the floods swept away several bridges, damaged several water plants and caused a reported gas leak.[23]

Maryland

Western Maryland was hard hit by Fran, mostly from flash flooding. About 650 homes were damaged and there was $100 million (1996 USD) in damage. This was the worst flooding event to hit Maryland since Hurricane Hazel and the January flood of 1996.[23]

District of Columbia

In the District of Columbia, Fran produced gusty winds and moderate rainfall. Gusts in the area were recorded in excess of 40 mph (64 km/h) and rainfall peaked near 3.5 in (89 mm). Minor flash flooding was reported on many streets, hampering travel and leaving several roads were closed.[31] These winds downed several trees in saturated soil.[32] A strong southerly wind and high tide led to a 5.1 ft (1.6 m) storm surge in Washington Harbor.[33] In addition to the storm surge, a river flood rivaling that of the January 1996 flood took place in the metropolitan area.[34] Throughout Washington, D.C., Fran left roughly $20 million in damage.[23]

Pennsylvania

About 15 Western Pennsylvania counties were impacted by flash flooding as rainfall up to 7 inches (178 mm) caused the Juniata River to overrun its banks.[22]

Ohio, Michigan, New England, and Canada

The remnants of Fran brought moderate to heavy rainfall to parts of eastern Ohio, especially along the coast of Lake Erie, as the storm moved through the region.[22] A maximum of 6.47 in (164 mm) of rain fell near Elyria in relation to Fran.[35] Sustained winds in the state were recorded around 30 mph (48 km/h) and gusts reached 60 mph (97 km/h). These winds downed numerous trees and power lines, some of which fell on cars and homes. Agricultural land and the region sustained significant damage.[36] In Cleveland, the city zoo sustained some flood damage and the monkey island was completely inundated.[37] In Cuyahoga County at least 90 homes reported basement flooding.[38] Widespread street and basement flooding took place across Lorain County, with some areas reporting standing water several days after Fran's passage.[39] Throughout Ohio, the remnants of Fran left roughly $40 million in damage and no loss of life.[3][40]

Continuing northward, Fran moved into southern Canada on September 7; however, the outer bands of the storm brought some rainfall to extreme eastern Michigan. In Port Huron, a state maximum amount of 4.07 in (103 mm) of rain fell during the storm's passage.[35] No known flooding or damage took place throughout the state.[40] Turning northeast and becoming extratropical, Fran brought scattered rainfall to parts of New England. A small area around Boston, Massachusetts received the heaviest rain in the region, peaking at 5.53 in (140 mm) in East Wareham. Isolated areas of 1 to 2 in (25 to 51 mm) of rain fell across portions of Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine before Fran dissipated over eastern Canada on September 8.[41] In nearby southern Canada, the remnants of Fran had little impact in Ontario, other than causing rain delays in a minor t-ball tournament, producing light to moderate rainfall between 1.8 and 2.6 in (45 and 65 mm).[42]

Aftermath

The Cape Fear River watershed was devastated by Fran. Severe water quality problems persisted for weeks. The Northeast Cape Fear river suffered a massive fish kill. Sewage treatment plant failures led to millions of gallons of raw and partially treated human sewage to flow into area rivers. Dissolved oxygen content fell to nearly zero across the Cape Fear and Northeast Cape Fear Rivers for over three weeks, which led to hypoxia in the Cape Fear estuary for several weeks. Ammonium and phosphorus levels increased, with concentrations of phosphorus reaching a 27-year high.[43]

Retirement

Because of the damage in North Carolina, the Virginias, and elsewhere in the United States, the name Fran was retired in the spring of 1997, and will never again be used for another Atlantic hurricane. It was replaced with Fay in the 2002 season.

See also

References

- ↑ Supal, Linnie. "NC Residents Remember Hurricane Fran 20 Years Later". Spectrum News. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ↑ Hurricane Research Division (2012). "Chronological List of All Hurricanes which Affected the Continental United States: 1851-2012". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Max Mayfield (October 10, 1996). "Hurricane Fran Preliminary Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ↑ Staff Writer (August 26, 1996). "Tropical outlook". The Victoria Advocate. p. 9. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ↑ Steve Stone (August 27, 1996). "Meteorologists Say Edouard's Tougher Than Satellites Show". The Virginian-Pilot. p. A2. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ↑ "Hurricane Fran: September 5, 1996".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zevin, Susan (July 1997). "Hurricane Fran" (PDF). Service Assessment. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "Hurricane Fran heads for Bahamas". Daily Courier. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 3, 199. p. 3A. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/tcr/AL061996_Fran.pdf

- ↑ Merzer, Martin (September 3, 1996). "Hurricane Fran makes track for Florida coast". The Ledger. Miami. The Miami Herald. p. 1. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "Hurricane Fran bearing down on Southeast". The Augusta Chronicle. Miami. The Associated Press. September 3, 1996. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "Georgia EMCs Gear Up for Hurricane Fran". PR Newswire Association, LLC. Atlanta, Georgia. PR Newswire. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ↑ "Florida Event Report: Hurricane". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ "South Carolina Event Report: High Winds". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "South Carolina Event Report: High Winds". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "South Carolina Event Report: High Winds". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "South Carolina Event Report: Hurricane". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "South Carolina Event Report: High Winds". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "South Carolina Event Report: Hurricane". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ Davie Poplar

- 1 2 3 4 David M. Roth. Hurricane Fran Rainfall Page. Retrieved on 2007-12-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 National Weather Service (July 1997). "Service Assessment: Hurricane Fran" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Hurricane Fran".

- ↑ "The Year Two Hurricanes Hit North Carolina".

- ↑ Hurricane Fran, NWS Newport/Moorhead, NC

- ↑ "Hurricane Fran Situation Report". Commonwealth of Virginia. 1996-09-09. Archived from the original on 2006-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ "Flooding the Zone : Hurricane Fran Sent Pete Jenkins' House Onto a Football Field and Into a Controversy". Los Angeles Times. 1996-09-22. Retrieved 2011-03-26.

- ↑ "Hurricane Fran Situation Report". Commonwealth of Virginia. 1996-09-08. Archived from the original on 2006-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ "Hurricane Fran Situation Report". Commonwealth of Virginia. 1996-09-07. Archived from the original on 2006-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ↑ "District of Columbia Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "District of Columbia Event Report: High Winds". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "District of Columbia Event Report: Storm Surge". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "District of Columbia Event Report: River Flooding". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- 1 2 David Roth (2010). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the Midwest". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Ohio Event Report: High Winds". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Ohio Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Ohio Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ "Ohio Event Report: Flash Flood". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- 1 2 "NCDC Storm Events Database". National Climatic Data Center. 2010. Archived from the original on August 1, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ↑ Roth, David M (May 12, 2022). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the New England United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Richard Lafortune; Diane Oullet (1997). "Canadian Tropical Cyclone Season Summary for 1996". Canadian Hurricane Centre. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ Michael A. Mallin; Martin H. Posey; G. Christopher Shank; Matthew R. McIver; Scott H. Ensign; Troy D. Alphin (May 21, 1998). "Hurricane Effects on Water Quality and Benthos in the Cape Fear Watershed: Natural and Anthropogenic Impacts". Ecological Applications. Ecological Applications: Vol. 9, No. 1. 9: 350–362. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1999)009[0350:HEOWQA]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1051-0761. Retrieved June 19, 2009.