| Old Uyghur | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Uyghur Khaganate, Qocho, Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom |

| Region | Mongolia, Hami, Turpan, Gansu |

| Era | 9th–14th century |

Turkic

| |

| Old Turkic script,[1] Old Uyghur alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | oui |

| Glottolog | oldu1238 |

Old Uyghur (simplified Chinese: 回鹘语; traditional Chinese: 回鶻語; pinyin: Huíhú yǔ) was a Turkic language which was spoken in Qocho from the 9th–14th centuries and in Gansu.

History

Old Uyghur evolved from Old Turkic, a Siberian Turkic language, after the Uyghur Khaganate broke up and remnants of it migrated to Turfan, Qomul (later Hami), and Gansu in the ninth century.

The Uyghurs in Turfan and Qomul founded Qocho and adopted Manichaeism and Buddhism as their religions, while those in Gansu first founded the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom and became subjects of the Western Xia; their descendants are the Yugurs of Gansu. The Western Yugur language is the descendant of Old Uyghur.[2]

The Kingdom of Qocho survived as a client state of the Mongol Empire but was conquered by the Muslim Chagatai Khanate, which conquered Turfan and Qomul and Islamized the region. Old Uyghur then became extinct in Turfan and Qomul.

The Uyghur language that is the official language of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region is not descended from Old Uyghur. It is a descendant of the Karluk languages spoken in the Kara-Khanid Khanate,[3] in particular the Khākānī language described by Mahmud al-Kashgari.

Features

Old Uyghur had an anticipating counting system and a copula dro, which is passed on to Western Yugur.[4]

Literature

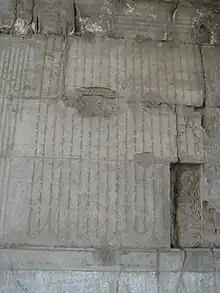

Much of Old Uyghur literature is religious texts regarding Manichaeism and Buddhism,[5] with examples found among the Dunhuang manuscripts. Multilingual inscriptions including Old Uyghur can be found at the Cloud Platform at Juyong Pass and the Stele of Sulaiman.

Script

Qocho, the Uyghur kingdom created in 843, originally used the "runic" Old Turkic alphabet with a "anïγ" dialect. The Old Uyghur alphabet was adopted from local inhabitants, along with a "ayïγ" dialect, when they migrated into Turfan after 840.[6]

References

Citations

- ↑ Marcel Erdal (1991). Old Turkic Word Formation: A Functional Approach to the Lexicon. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-3-447-03084-7.

- ↑ Clauson 1965, p. 57.

- ↑ Arik 2008, p. 145

- ↑ Chen et al, 1985

- ↑ "西域、 敦煌文献所见回鹊之佛经翻译". Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ↑ Sinor, D. (1998), "Chapter 13 – Language situation and scripts", in Asimov, M.S.; Bosworth, C.E. (eds.), History of Civilisations of Central Asia, vol. 4 part II, UNESCO Publishing, p. 333, ISBN 81-208-1596-3

Sources

- Arik, Kagan (2008). Austin, Peter (ed.). One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520255609. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Chén Zōngzhèn & Léi Xuǎnchūn. 1985. Xībù Yùgùyǔ Jiānzhì [Concise grammar of Western Yugur]. Peking.

- Clauson, Gerard (April 1965). "Review An Eastern Turki-English Dictionary by Gunnar Jarring". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1/2). JSTOR 25202808.

- Coene, Frederik (8 October 2009). The Caucasus – An Introduction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-87071-6.

Further reading

- Tisastvustik; ein in türkischer Sprache bearbeitetes buddhistisches Sutra. I. Transcription und Übersetzung von W. Radloff. II. Bemerkungen zu den Brahmiglossen des Tisastvustik-Manuscripts (Mus. A. Kr. VII) von Baron A. von Stäel-Holstein (1910)

- Kahar Barat (2000). The Uygur-Turkic Biography of the Seventh-Century Chinese Buddhist Pilgrim Xuanzang: Ninth and Tenth Chapters. Indiana University, Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies. ISBN 978-0-933070-46-2.

- Giovanni Stary (1996). Proceedings of the 38th Permanent International Altaistic Conference (PIAC): Kawasaki, Japan, August 7-12, 1995. Harrassowitz Verlag in Kommission. ISBN 978-3-447-03801-0.