.webp.png.webp)

The nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are commitments that countries make to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions as part of climate change mitigation. The plans that countries make also include policies and measures that they plan to implement as a contribution to achieve the global targets set out in the Paris Agreement. NDCs play a central role in guiding countries toward achieving these temperature targets (keeping global temperature increases well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels).

NDCs embody efforts by each country to reduce national emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change.[2] The Paris Agreement requires each of the 193 Parties to prepare, communicate and maintain NDCs outlining what they intend to achieve.[2] NDCs must be updated every five years.[2]

Prior to the Paris Agreement in 2015, the NDCs were referred to as intended nationally determined contributions (INDCs) and were non-binding. The INDCs were initial, voluntary pledges made by countries, whereas the NDCs are more committed but also not legally binding.

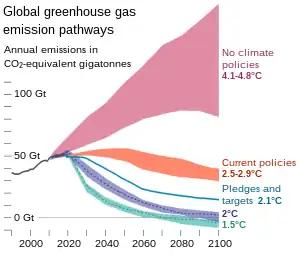

The rates of emissions reductions need to increase by 80% beyond NDCs to likely meet the 2 °C upper target range of the Paris Agreement (data as of 2021).[3] The probabilities of major emitters meeting their NDCs without such an increase is very low. Therefore, with current trends the probability of staying below 2 °C of warming is only 5% – and if NDCs were met and continued post-2030 by all signatory systems the probability would be 26%.[3][1]

Role within Paris Agreement

Nationally determined contributions (NDCs) are "at the heart of the Paris Agreement and the achievement of its long-term goals".[4]

Countries determine themselves what contributions they should make to achieve the aims of the treaty. As such, these plans are called nationally determined contributions (NDCs).[5] Article 3 requires NDCs to be "ambitious efforts" towards "achieving the purpose of this Agreement" and to "represent a progression over time".[5] The contributions should be set every five years and are to be registered by the UNFCCC Secretariat.[6] Each further ambition should be more ambitious than the previous one, known as the principle of progression.[7] Countries can cooperate and pool their nationally determined contributions. The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions pledged during the 2015 Climate Change Conference are converted to NDCs when a country ratifies the Paris Agreement, unless they submit an update.[8][9]

The Paris Agreement does not prescribe the exact nature of the NDCs. At a minimum, they should contain mitigation provisions, but they may also contain pledges on adaptation, finance, technology transfer, capacity building and transparency.[10] Some of the pledges in the NDCs are unconditional, but others are conditional on outside factors such as getting finance and technical support, the ambition from other parties or the details of rules of the Paris Agreement that are yet to be set. Most NDCs have a conditional component.[11]

While the NDCs themselves are not binding, the procedures surrounding them are. These procedures include the obligation to prepare, communicate and maintain successive NDCs, set a new one every five years, and provide information about the implementation.[12] There is no mechanism to force[13] a country to set a NDC target by a specific date, nor to meet their targets.[14][15] There will be only a name and shame system[16] or as János Pásztor, the former U.N. assistant secretary-general on climate change, stated, a "name and encourage" plan.[17]Process

.png.webp)

The establishment of NDCs combine the top-down system of a traditional international agreement with bottom-up system-in elements through which countries put forward their own goals and policies in the context of their own national circumstances, capabilities, and priorities, with the goal of reducing global greenhouse gas emissions enough limit anthropogenic temperature rise to well below 2 °C (3.6 °F) above pre-industrial levels; and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F).[19][20]

NDCs contain steps taken towards emissions reductions and also aim to address steps taken to adapt to climate change impacts, and what support the country needs, or will provide, to address climate change. After the initial submission of INDCs in March 2015, an assessment phase followed to review the impact of the submitted INDCs before the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference.[19]

The information gathered from parties' individual reports and reviews, along with the more comprehensive picture attained through the "global stocktake" will, in turn, feed back into and shape the formulation of states' subsequent pledges. The logic, overall, is that this process will offer numerous avenues where domestic and transnational political processes can play out, facilitating the making of more ambitious commitments and putting pressure on states to comply with their nationally determined goals.[21]

NDCs are the first greenhouse gas targets under the UNFCCC that apply equally to both developed and developing countries.[19]

Timeframe

The NDCs should be set every five years and are to be registered by the UNFCCC Secretariat.[22] The timeframes facilitate periodic updates to reflect changing circumstances or increased ambitions.

NDCs are established independently by the parties (countries or regional groups of countries) in question. However, they are set within a binding iterative "catalytic" framework designed to ratchet up climate action over time.[4] Once states have set their initial NDCs, these are expected to be updated on a 5-year cycle. Biennial progress reports are to be published that track progress toward the objectives set out in states' NDCs. These will be subjected to technical review, and will collectively feed into a global stocktaking exercise, itself operating on an offset 5-year cycle, where the overall sufficiency of NDCs collectively will be assessed.

Current status

Emission reductions offered of current NDCs

Through the Climate Change Performance Index, Climate Action Tracker[23] and the Climate Clock, people can see on-line how well each individual country is currently on track to achieving its Paris agreement commitments. These tools however only give a general insight in regards to the current collective and individual country emission reductions. They do not give insight in regards on the emission reductions offered per country, for each measure proposed in the NDC.

Sustainable development goals

The Sustainable Development Goal 13 on climate action has an indicator related to NDCs for its second target: Indicator 13.2.1 is the "Number of countries with nationally determined contributions, long-term strategies, national adaptation plans, strategies as reported in adaptation communications and national communications".[24] As of 31 March 2020, 186 parties (185 countries plus the European Union) had communicated their first NDCs to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat. A report by the UN stated in 2020 that: "the world is way off track in meeting this target at the current level of nationally determined contributions."[25]

Critique

The rates of emissions reductions need to increase by 80% beyond NDCs to likely meet the 2 °C upper target range of the Paris Agreement (data as of 2021).[3] The probabilities of major emitters meeting their NDCs without such an increase is very low. Therefore, with current trends the probability of staying below 2 °C of warming is only 5% – and if NDCs were met and continued post-2030 by all signatory systems the probability would be 26%.[3][1]

The effectiveness of the Paris Agreement to reach its climate goals is under debate, with most experts saying it is insufficient for its more ambitious goal of keeping global temperature rise under 1.5 °C.[26][27] Many of the exact provisions of the Paris Agreement have yet to be straightened out, so that it may be too early to judge effectiveness.[26] According to the 2020 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), with the current climate commitments of the Paris Agreement, global mean temperatures will likely rise by more than 3 °C by the end of the 21st century. Newer net zero commitments were not included in the NDCs, and may bring down temperatures a further 0.5 °C.[28]

With initial pledges by countries inadequate, faster and more expensive future mitigation would be needed to still reach the targets.[29] Furthermore, there is a gap between pledges by countries in their NDCs and implementation of these pledges; one third of the emission gap between the lowest-costs and actual reductions in emissions would be closed by implementing existing pledges.[30] A pair of studies in Nature found that as of 2017 none of the major industrialized nations were implementing the policies they had pledged, and none met their pledged emission reduction targets,[31] and even if they had, the sum of all member pledges (as of 2016) would not keep global temperature rise "well below 2 °C".[32][33]

In 2021, a study using a probabilistic model concluded that the rates of emissions reductions would have to increase by 80% beyond NDCs to likely meet the 2 °C upper target of the Paris Agreement, that the probabilities of major emitters meeting their NDCs without such an increase is very low. It estimated that with current trends the probability of staying below 2 °C of warming is 5% – and 26% if NDCs were met and continued post-2030 by all signatories.[34]

As of 2020, there is little scientific literature on the topics of the effectiveness of the Paris Agreement on capacity building and adaptation, even though they feature prominently in the Paris Agreement. The literature available is mostly mixed in its conclusions about loss and damage, and adaptation.[26]

According to the stocktake report, the agreement has a significant effect: while in 2010 the expected temperature rise by 2100 was 3.7–4.8 °C, at COP 27 it was 2.4–2.6°C and if all countries will fulfill their long-term pledges even 1.7–2.1 °C. Despite it, the world is still very far from reaching the aim of the agreement: limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees. For doing this, emissions must peak by 2025.[35][36]History

NDCs have an antecedent in the pledge and review system that had been considered by international climate change negotiators back in the early 1990s.[37] All countries that were parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) were asked to publish their intended nationally determined contributions (INDC) at the 2013 United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Warsaw, Poland, in November 2013.[38][39] The intended contributions were determined without prejudice to the legal nature of the contributions.[39] The term was intended as a compromise between "quantified emissions limitation and reduction objective" (QELROs) and "Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions" (NAMAs) that the Kyoto Protocol used to describe the different legal obligations of developed and developing countries.

After the Paris Agreement entered into force in 2016, the INDCs became the first NDC when a country ratified the agreement unless it decided to submit a new NDC at the same time. NDCs are the first greenhouse gas targets under the UNFCCC that apply equally to both developed and developing countries.[19]

Intended nationally determined contributions (INDC) submissions

On 27 February 2015, Switzerland became the first nation to submit its INDC.[40] Switzerland said that it had experienced a temperature rise of 1.75 °C since 1864, and aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions 50% by 2030.[41]

India submitted its INDC to the UNFCCC in October 2015, committing to cut the emissions intensity of GDP by 33–35% by 2030 from 2005 levels.[42] On its submission, India wrote that it needs "at least USD 2.5 trillion" to achieve its 2015–2030 goals, and that its "international climate finance needs" will be the difference over "what can be made available from domestic sources."[43]

Of surveyed countries, 85% reported that they were challenged by the short time frame available to develop INDCs. Other challenges reported include difficulty to secure high-level political support, a lack of certainty and guidance on what should be included in INDCs, and limited expertise for the assessment of technical options. However, despite challenges, less than a quarter of countries said they had received international support to prepare their INDCs, and more than a quarter indicated they are still applying for international support.[44] The INDC process and the challenges it presents are unique to each country and there is no "one-size-fits-all" approach or methodology.[45]

By country

Information about NDCs by country are shown in some of the country climate change articles below.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Liu, Peiran R.; Raftery, Adrian E. (9 February 2021). "Country-based rate of emissions reductions should increase by 80% beyond nationally determined contributions to meet the 2 °C target". Communications Earth & Environment. 2 (1): 29. Bibcode:2021ComEE...2...29L. doi:10.1038/s43247-021-00097-8. ISSN 2662-4435. PMC 8064561. PMID 33899003.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

Available under CC BY 4.0. - 1 2 3 4 "Nationally determined contributions to climate change". Our World in Data. Retrieved 2024-01-11.

- 1 2 3 4 "Limiting warming to 2 C requires emissions reductions 80% above Paris Agreement targets". phys.org. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- 1 2 "Nationally Determined Contributions". unfccc. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- 1 2 Article 3, Paris Agreement (2015)

- ↑ Article 4(9), Paris Agreement (2015)

- ↑ Articles 3, 9(3), Paris Agreement (2015)

- ↑ Taibi, Fatima-Zahra; Konrad, Susanne; Bois von Kursk, Olivier (2020). Sharma, Anju (ed.). Pocket Guide to NDCs: 2020 Edition (PDF). European Capacity Building Initiative. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Staff (22 November 2019). "National Climate Action under the Paris Agreement". World Resources Institute. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ↑ Taibi, Fatima-Zahra; Konrad, Susanne; Bois von Kursk, Olivier (2020). Sharma, Anju (ed.). Pocket Guide to NDCs: 2020 Edition (PDF). European Capacity Building Initiative. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Taibi, Fatima-Zahra; Konrad, Susanne; Bois von Kursk, Olivier (2020). Sharma, Anju (ed.). Pocket Guide to NDCs: 2020 Edition (PDF). European Capacity Building Initiative. pp. 32–33. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ↑ Bodansky, Daniel (2016). "The Legal Character of the Paris Agreement". Review of European, Comparative & International Environmental Law. 25 (2): 142–150. doi:10.1111/reel.12154. ISSN 2050-0394. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ↑ Reguly, Eric; McCarthy, Shawn (14 December 2015). "Paris climate accord marks shift toward low-carbon economy". Globe and Mail. Toronto, Canada. Archived from the original on 13 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Mark, Kinver (14 December 2015). "COP21: What does the Paris climate agreement mean for me?". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Davenport, Coral (12 December 2015). "Nations Approve Landmark Climate Accord in Paris". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Chauhan, Chetan (14 December 2015). "Paris climate deal: What the agreement means for India and the world". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Falk, Pamela (12 December 2015). "Climate negotiators strike deal to slow global warming". CBS News. Archived from the original on 13 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Ritchie, Roser, Mispy, Ortiz-Ospina. "Measuring progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals." (SDG 13) SDG-Tracker.org, website (2018).

- 1 2 3 4 "What is an INDC?". World Resources Institute. 2014-10-17. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ The Paris Agreement's long-term temperature goal is to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 °C (3.6 °F) above pre-industrial levels; and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 °C (2.7 °F)s

- ↑ Falkner, Robert (2016). "The Paris Agreement and the New Logic of International Climate Politics" (PDF). International Affairs. 92 (5): 1107–25. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12708.

- ↑ Article 4(9), Paris Agreement (2015)

- ↑ "Countries | Climate Action Tracker". climateactiontracker.org.

- ↑ United Nations (2017) Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 6 July 2017, Work of the Statistical Commission pertaining to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/71/313)

- ↑ "SDG Report 2020". UN Stats. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- 1 2 3 Raiser, Kilian; Kornek, Ulrike; Flachsland, Christian; Lamb, William F (19 August 2020). "Is the Paris Agreement effective? A systematic map of the evidence". Environmental Research Letters. 15 (8): 083006. Bibcode:2020ERL....15h3006R. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab865c. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ↑ Maizland, Lindsay (29 April 2021). "Global Climate Agreements: Successes and Failures". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ United Nations Environment Programme (2020). Emissions Gap Report 2020. Nairobi. p. XXI. ISBN 978-92-807-3812-4. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Paris Agreement, Decision 1/CP.21, Article 17" (PDF). UNFCCC secretariat. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- ↑ Roelfsema, Mark; van Soest, Heleen L.; Harmsen, Mathijs; van Vuuren, Detlef P.; Bertram, Christoph; den Elzen, Michel; Höhne, Niklas; Iacobuta, Gabriela; Krey, Volker; Kriegler, Elmar; Luderer, Gunnar (29 April 2020). "Taking stock of national climate policies to evaluate implementation of the Paris Agreement". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 2096. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.2096R. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-15414-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7190619. PMID 32350258.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Minor grammatical amendments were made.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 4.0 license. Minor grammatical amendments were made. - ↑ Victor, David G.; Akimoto, Keigo; Kaya, Yoichi; Yamaguchi, Mitsutsune; Cullenward, Danny; Hepburn, Cameron (3 August 2017). "Prove Paris was more than paper promises". Nature. 548 (7665): 25–27. Bibcode:2017Natur.548...25V. doi:10.1038/548025a. PMID 28770856. S2CID 4467912.

- ↑ Rogelj, Joeri; den Elzen, Michel; Höhne, Niklas; Fransen, Taryn; Fekete, Hanna; Winkler, Harald; Schaeffer, Roberto; Sha, Fu; Riahi, Keywan; Meinshausen, Malte (30 June 2016). "Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C" (PDF). Nature. 534 (7609): 631–639. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..631R. doi:10.1038/nature18307. PMID 27357792. S2CID 205249514. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ↑ Mooney, Chris (29 June 2016). "The world has the right climate goals – but the wrong ambition levels to achieve them". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 June 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ↑ Liu, Peiran R.; Raftery, Adrian E. (9 February 2021). "Country-based rate of emissions reductions should increase by 80% beyond nationally determined contributions to meet the 2 °C target". Communications Earth & Environment. 2 (1): 29. Bibcode:2021ComEE...2...29L. doi:10.1038/s43247-021-00097-8. ISSN 2662-4435. PMC 8064561. PMID 33899003.

Available under CC BY 4.0.

Available under CC BY 4.0. - ↑ Nilsen, Ella (8 September 2023). "World isn't moving fast enough to cut pollution and keep warming below 2 degrees Celsius, UN scorecard says". CNN. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ↑ "Technical dialogue of the first global stocktake Synthesis report by the co-facilitators on the technical dialogue" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ↑ Andrew Dessler; Edward A Parson (2020). The Science and Politics of Global Climate Change: A Guide to the Debate. Cambridge University Press. pp. 28, 137–148, 175–179, 198–200. ISBN 978-1-316-63132-4.

- ↑ "adopted by the Conference of the Parties of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change at its nineteenth session" (PDF). United Nations. 31 January 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- 1 2 "INDC - Climate Policy Observer". Climate Policy Observer. Archived from the original on 2017-02-11. Retrieved 2015-12-15.

- ↑ "INDC - Submissions". www4.unfccc.int. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ "Switzerland, EU are the first to submit 'Intended Nationally Determined Contributions'". downtoearth.org.in. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ "India to cut emissions intensity". The Hindu. 2015-10-03. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ↑ "India's intended nationally determined contribution" (PDF). United Nations FCCC. Section 5.1, Third Paragraph. p. 31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ "Second wave of climate change proposals (INDCs) expected in September after a first wave in March". newclimate.org. 2015-03-05. Retrieved 2015-03-22.

- ↑ "Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs): Sharing lessons and resources". Climate and Development Knowledge Network. Retrieved 2015-04-15.

External links

- NDC portal at UNFCCC website

- "NDC Synthesis Report". United Nations Climate Change Commission. 26 February 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.