| Mount Hood | |

|---|---|

Mount Hood reflected in Mirror Lake | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 11,249 ft (3,429 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 7,706 ft (2,349 m)[2] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 45°22′25″N 121°41′45″W / 45.37361°N 121.69583°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Language of name | Multnomah |

| Geography | |

Location relative to other Oregon volcanoes

| |

| Location | Clackamas / Hood River counties, Oregon, U.S. |

| Parent range | Cascade Range |

| Topo map | USGS Mount Hood South |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | More than 500,000 years[3] |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Last eruption | 21 September 1865 to January 1866[4] |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | July 11, 1857, by Henry Pittock, W. Lymen Chittenden, Wilbur Cornell, and the Rev. T. A. Wood[5] |

| Easiest route | Rock and glacier climb |

Mount Hood is an active stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc. It was formed by a subduction zone on the Pacific coast and rests in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is located about 50 mi (80 km) east-southeast of Portland, on the border between Clackamas and Hood River counties. In addition to being Oregon's highest mountain, it is one of the loftiest mountains in the nation based on its prominence, and it offers the only year-round lift-served skiing in North America.

The height assigned to Mount Hood's snow-covered peak has varied over its history. Modern sources point to three different heights: 11,249 ft (3,429 m), a 1991 adjustment of a 1986 measurement by the U.S. National Geodetic Survey (NGS),[1] 11,240 ft (3,426 m) based on a 1993 scientific expedition,[6] and 11,239 ft (3,425.6 m)[7] of slightly older origin. The peak is home to 12 named glaciers and snowfields. It is the highest point in Oregon and the fourth highest in the Cascade Range.[8] Mount Hood is considered the Oregon volcano most likely to erupt,[9] though based on its history, an explosive eruption is unlikely. Still, the odds of an eruption in the next 30 years are estimated at between 3 and 7%, so the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) characterizes it as "potentially active", but the mountain is informally considered dormant.[10]

Establishments

Timberline Lodge is a National Historic Landmark located on the southern flank of Mount Hood just below Palmer Glacier, with an elevation of about 6,000 ft (1,800 m).[11]

The mountain has six ski areas: Timberline, Mount Hood Meadows, Ski Bowl, Cooper Spur, Snow Bunny, and Summit. They total over 4,600 acres (7.2 sq mi; 19 km2) of skiable terrain; Timberline, with one lift having a base at nearly 6,940 ft (2,120 m), offers the only year-round lift-served skiing in North America.[12]

There are a few remaining shelters on Mount Hood still in use today. Those include the Coopers Spur, Cairn Basin, and McNeil Point shelters as well as the Tilly Jane A-frame cabin. The summit was home to a fire lookout in the early 1900s; however, the lookout did not withstand the weather and no longer remains today.[13]

Mount Hood is within the Mount Hood National Forest, which comprises 1,067,043 acres (1,667 sq mi; 4,318 km2) of land, including four designated wilderness areas that total 314,078 acres (491 sq mi; 1,271 km2), and more than 1,200 mi (1,900 km) of hiking trails.[14][15]

The most northwestern pass around the mountain is called Lolo Pass. Native Americans crossed the pass while traveling between the Willamette Valley and Celilo Falls.[16]

Naming

Indigenous names

The name Wy'east has been associated with Mount Hood for more than a century, but no evidence suggests that it is a genuine name for the mountain in any indigenous language. The name was possibly inspired by an 1890 work of author Frederic Balch, although Balch does not use it himself.[17][18][19] In one version of Balch's story, the two sons of the Great Spirit Sahale fell in love with the beautiful maiden Loowit, who could not decide which to choose. The two braves, Wy'east and Pahto (unnamed in his novel, but appearing in a later adaptation), burned forests and villages in their battle over her. Sahale became enraged and smote the three lovers. Seeing what he had done, he erected three mountain peaks to mark where each fell. He made beautiful Mount St. Helens for Loowit, proud and erect Mount Hood for Wy'east, and the somber Mount Adams for the mourning Pahto.[20]

There are other versions of the legend. In another telling, Wy'east (Hood) battles Pahto (Adams) for the fair La-wa-la-clough (St. Helens). Or again Wy'east, the chief of the Multnomah tribe, competed with the chief of the Klickitat tribe. Their great anger led to their transformation into volcanoes. Their battle is said to have destroyed the Bridge of the Gods and thus created the great Cascades Rapids of the Columbia River.[21]

The mountain sits partly inside the reservation of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs. Three languages are spoken among this confederacy: Sahaptin, Upper Chinook/Kiksht (Wasco) and Numu (Paiute). Therefore, any attempt to restore the mountain's original indigenous name would require agreement on which language's name to use.

Current name

The mountain was given its present name on October 29, 1792, by Lt. William Broughton, a member of Captain George Vancouver's exploration expedition. Lt. Broughton observed its peak while at Belle Vue Point of what is now called Sauvie Island during his travels up the Columbia River, writing, "A very high, snowy mountain now appeared rising beautifully conspicuous in the midst of an extensive tract of low or moderately elevated land [location of today's Vancouver, Washington] lying S 67 E., and seemed to announce a termination to the river." Lt. Broughton named the mountain after Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount Hood, a British Admiral at the Battle of the Chesapeake.[8]

Lewis and Clark spotted the mountain on October 18, 1805. A few days later at what would become The Dalles, Clark wrote, "The pinnacle of the round topped mountain, which we saw a short distance below the banks of the river, is South 43-degrees West of us and about 37 mi (60 km). It is at this time topped with snow. We called this the Falls Mountain, or Timm Mountain." Timm was the native name for Celilo Falls. Clark later noted that it was also Vancouver's Mount Hood.[22][23]

Two French explorers from the Hudson's Bay Company may have traveled into the Dog River area east of Mount Hood in 1818. They reported climbing to a glacier on "Montagne de Neige" (Mountain of Snow), probably Eliot Glacier.[22]

Namesakes

There have been two United States Navy ammunition ships named for Mount Hood. USS Mount Hood (AE-11) was commissioned in July 1944 and was destroyed in November 1944 while at anchor in Manus Naval Base, Admiralty Islands. Her explosive cargo ignited, resulting in 45 confirmed dead, 327 missing and 371 injured.[24] A second ammunition ship, AE-29, was commissioned in May 1971 and decommissioned in August 1999.[25]

Volcanic activity

The glacially eroded summit area consists of several andesitic or dacitic lava domes; Pleistocene collapses produced avalanches and lahars (rapidly moving mudflows) that traveled across the Columbia River to the north. The eroded volcano has had at least four major eruptive periods during the past 15,000 years.[26]

The last three eruptions at Mount Hood occurred within the past 1,800 years from vents high on the southwest flank and produced deposits that were distributed primarily to the south and west along the Sandy and Zigzag rivers. The last eruptive period took place around 220 to 170 years ago, when dacitic lava domes, pyroclastic flows and mudflows were produced without major explosive eruptions. The prominent Crater Rock just below the summit is hypothesized to be the remains of one of these now-eroded domes. This period includes the last major eruption of 1781 to 1782 with a slightly more recent episode ending shortly before the arrival of the explorers Lewis and Clark in 1805. The latest minor eruptive event occurred in August 1907.[26][27]

The glaciers on the mountain's upper slopes may be a source of potentially dangerous lahars when the mountain next erupts. There are vents near the summit that are known for emitting gases such as carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide.[28] Prior to the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, the only known fatality related to volcanic activity in the Cascades occurred in 1934, when a climber suffocated in oxygen-poor air while exploring ice caves melted by fumaroles in Coalman Glacier on Mount Hood.[8]

Since 1950, there have been several earthquake swarms each year at Mount Hood, most notably in July 1980 and June 2002.[29][30] Seismic activity is monitored by the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Washington, which issues weekly updates (and daily updates if significant eruptive activity is occurring at a Cascades volcano).[31]

The most recent evidence of volcanic activity at Mount Hood consists of fumaroles near Crater Rock and hot springs on the flanks of the volcano.[32]

Monitoring controversy

A conflict exists between protecting public safety and protecting the environment. In 2014, a USGS employee, Dr. Seth Moran, proposed installing new instruments on Mount Hood to warn of volcanic activity. The instruments were installed at four different locations on the mountain, including:

- three seismometers to measure earthquakes,

- three Global Positioning System (GPS) instruments to measure ground movement,

- one instrument to measure gas emissions.

The proposed locations were in a protected wilderness area, tightly controlled by the United States Forest Service. The project was opposed by Wilderness Watch, a conservation group.[33]

Three monitoring stations were eventually installed on Mount Hood in 2020.[34]

Elevation

Mount Hood was first seen by European explorers in 1792 and is believed to have maintained a consistent summit elevation, varying by no more than a few feet due to mild seismic activity. Elevation changes since the 1950s are predominantly due to improved survey methods and model refinements of the shape of the Earth (see vertical reference datum). Despite the physical consistency, the estimated elevation of Mount Hood has varied substantially over the years, as seen in the following table:

| Date | Stated Elevation | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1854 | 18,361 ft (5,596 m) | Thomas J. Dryer[35] |

| 1854 | 19,400 ft (5,900 m) | Belden[35] |

| 1857 | 14,000 ft (4,300 m) | Mitchell's School Atlas[36] |

| 1866 | 17,600 ft (5,400 m) | Rev. Atkinson[35] |

| 1867 | 11,225 ft (3,421 m) | Col. Williamson[35] |

| 1916 | 11,253 ft (3,430 m) | Adm. Colbert[35] |

| 1939 | 11,245 ft (3,427 m) | Adm. Colbert[35] |

| 1980 | 11,239 ft (3,426 m) | USGS using NGVD 29[27] |

| 1991 | 11,249 ft (3,429 m) | U.S. National Geodetic Survey, 1986 measurement adjusted using NAVD 88[1] |

| 1993 | 11,240 ft (3,426 m) | Scientific expedition[6] and 11,239 ft (3,426 m)[7] of slightly older origin |

| 2008? | 11,235 ft (3,424 m) | Encyclopedia Britannica[37] |

Early explorers on the Columbia River estimated the elevation to be 10,000 to 12,000 ft (3,000 to 3,700 m). Two people in Thomas J. Dryer's 1854 expedition calculated the elevation to be 18,361 ft (5,596 m) and the tree line to be at 11,250 ft (3,430 m). Two months later, a Mr. Belden claimed to have climbed the mountain during a hunting trip and determined it to be 19,400 ft (5,900 m) upon which "pores oozed blood, eyes bled, and blood rushed from their ears." Sometime by 1866, Reverend G. H. Atkinson determined it to be 17,600 ft (5,400 m). A Portland engineer used surveying methods from a Portland baseline and calculated a height of between 18,000 and 19,000 ft (5,500 and 5,800 m). Many maps distributed in the late 19th century cited 18,361 ft (5,596 m), though Mitchell's School Atlas gave 14,000 ft (4,300 m) as the correct value. For some time, many references assumed Mount Hood to be the highest point in North America.[35]

Modern height surveys also vary, but not by the huge margins seen in the past. A 1993 survey by a scientific party that arrived at the peak's summit with 16 lb (7.3 kg) of electronic equipment reported a height of 11,240 ft (3,426 m), claimed to be accurate to within 1.25 in (32 mm).[6] Many modern sources likewise list 11,240 ft (3,426 m) as the height.[38][39][40] However, numerous others place the peak's height one foot lower, at 11,239 ft (3,426 m).[7][41][42] Finally, a height of 11,249 ft (3,429 m) has also been reported.[1][43][44][45]

Glaciers

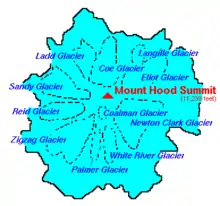

Mount Hood is host to 12[46][47] named glaciers or snow fields, the most visited of which is Palmer Glacier, partially within the Timberline Lodge ski area and on the most popular climbing route. The glaciers are almost exclusively above the 6,000 ft (1,800 m) level, which also is about the average tree line elevation on Mount Hood.[48] More than 80 percent of the glacial surface area is above 7,000 ft (2,100 m).[49]

The glaciers and permanent snow fields have an area of 3,331 acres (1,348 ha) and contain a volume of about 282,000 acre⋅ft (0.348 km3). Eliot Glacier is the largest glacier by volume at 73,000 acre⋅ft (0.09 km3), and has the thickest depth measured by ice radar at 361 ft (110 m). The largest glacier by surface area is the Coe-Ladd Glacier system at 531 acres (215 ha).[49]

Glaciers and snowfields cover about 80 percent of the mountain above the 6,900 ft (2,100 m) level. The glaciers declined by an average of 34 percent from 1907 to 2004. Glaciers on Mount Hood retreated through the first half of the 20th century, advanced or at least slowed their retreat in the 1960s and 1970s, and have since returned to a pattern of retreat.[50] The neo-glacial maximum extents formed in the early 18th century.[8]

During the last major glacial event between 29,000 and 10,000 years ago, glaciers reached down to the 2,600-to-2,300 ft (790-to-700 m) level, a distance of 9.3 mi (15.0 km) from the summit. The retreat released considerable outwash, some of which filled and flattened the upper Hood River Valley near Parkdale and formed Dee Flat.[8]

Older glaciation produced moraines near Brightwood and distinctive cuts on the southeast side; they may date to 140,000 years ago.[8]

Hiking

The Mount Hood forest is home to approximately 1,000 mi (1,600 km) of trails.[54] The Coopers Spur trail leads to 8,510 ft (2,590 m) in elevation, the highest reachable point one can gain on the mountain without requiring mountaineering gear.

The Timberline Trail, which circumnavigates the entire mountain and rises as high as 7,300 ft (2,200 m), was built in the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps. Typically, the 40.7 mi (65.5 km) hike is snow-free from late July until the autumn snows begin. The trail includes over 10,000 ft (3,000 m) of elevation gain and loss and can vary in distance year to year depending on river crossings. There are many access points, the shortest being a small walk from the Timberline Lodge. A portion of the Pacific Crest Trail is coincident with the Timberline Trail on the west side of Mount Hood.[55][56]

The predecessor of the Pacific Crest Trail was the Oregon Skyline Trail, established in 1920, which connected Mount Hood to Crater Lake.[57]

Climbing

Mount Hood is Oregon's highest point and a prominent landmark visible up to 100 mi (160 km) away. About 10,000 people attempt to climb Mount Hood each year.[58] It has convenient access, though it presents some technical climbing challenges. There are no trails to the summit, with even the "easier" southside climbing route constituting a technical climb with crevasses, falling rocks, and often inclement weather. Ropes, ice axes, crampons and other technical mountaineering gear are necessary.[59] Peak climbing season is generally from April to mid-June.[60]

There are six main routes to approach the mountain, with about 30 total variations for summiting. The climbs range in difficulty from class 2 to class 5.9+ (for Acrophobia).[61] The most popular route, dubbed the south route, begins at Timberline Lodge and proceeds up Palmer Glacier to Crater Rock, the large prominence at the head of the glacier. The route goes east around Crater Rock and crosses the Coalman Glacier on the Hogsback, a ridge spanning from Crater Rock to the approach to the summit. The Hogsback terminates at a bergschrund where the Coalman Glacier separates from the summit rock headwall. The route continues to the Pearly Gates, a gap in the summit rock formation, then right onto the summit plateau and the summit proper.[62]

Technical ice axes, fall protection, and experience are now recommended in order to attempt the left chute variation or Pearly Gates ice chute. The Forest Service recommends several other route options due to these changes in conditions (e.g. "Old Chute," West Crater Rim, etc.).[63]

Climbing accidents

As of May 2002, more than 130 people had died in climbing-related accidents since records have been kept on Mount Hood, the first in 1896.[64] Incidents in May 1986, December 2006, and December 2009 attracted intense national and international media interest. Though avalanches are a common hazard on other glaciated mountains, most Mount Hood climbing deaths are the result of falls and hypothermia.[65] Around 50 people require rescue per year.[66] 3.4 percent of search and rescue missions in 2006 were for mountain climbers.[67]

Climate

The summit of Mount Hood has a typical dry-summer alpine climate (Köppen: ETs), with temperatures below 32 °F (0 °C) eight months of the year and no month with an average temperature above 50 °F (10 °C). Even in the hottest months, nightly average temperatures often dip below 32 °F (0 °C), and frost occurs almost every day, even in summer or the hottest time of year. Otherwise, all months have a dew point below 32 °F (0 °C).

| Climate data for Mount Hood, 1991–2020 normals (3001m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 24.5 (−4.2) |

23.8 (−4.6) |

24.7 (−4.1) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

37.0 (2.8) |

44.0 (6.7) |

54.9 (12.7) |

55.2 (12.9) |

50.1 (10.1) |

39.7 (4.3) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

36.1 (2.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 18.9 (−7.3) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

27.0 (−2.8) |

33.2 (0.7) |

42.6 (5.9) |

43.0 (6.1) |

38.5 (3.6) |

30.2 (−1.0) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

17.9 (−7.8) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 13.3 (−10.4) |

10.0 (−12.2) |

9.0 (−12.8) |

10.5 (−11.9) |

16.9 (−8.4) |

22.4 (−5.3) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

30.7 (−0.7) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

15.7 (−9.1) |

12.5 (−10.8) |

18.3 (−7.6) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 17.99 (457) |

13.55 (344) |

14.29 (363) |

11.40 (290) |

7.67 (195) |

5.84 (148) |

1.37 (35) |

1.82 (46) |

4.57 (116) |

10.86 (276) |

17.45 (443) |

18.83 (478) |

125.64 (3,191) |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 12.8 (−10.7) |

9.6 (−12.4) |

8.6 (−13.0) |

10.5 (−11.9) |

16.0 (−8.9) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

26.5 (−3.1) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

21.4 (−5.9) |

18.4 (−7.6) |

15.1 (−9.4) |

12.7 (−10.7) |

16.5 (−8.6) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[68] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Mount Hood 45.3744 N, 121.6999 W, Elevation: 10,407 ft (3,172 m) (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 22.8 (−5.1) |

22.1 (−5.5) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

26.6 (−3.0) |

35.3 (1.8) |

42.4 (5.8) |

53.2 (11.8) |

53.5 (11.9) |

48.4 (9.1) |

38.1 (3.4) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

34.5 (1.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 17.1 (−8.3) |

15.1 (−9.4) |

15.0 (−9.4) |

17.6 (−8.0) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

31.4 (−0.3) |

40.8 (4.9) |

41.1 (5.1) |

36.7 (2.6) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

20.1 (−6.6) |

16.2 (−8.8) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 11.4 (−11.4) |

8.0 (−13.3) |

7.1 (−13.8) |

8.5 (−13.1) |

14.9 (−9.5) |

20.5 (−6.4) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

25.0 (−3.9) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

13.9 (−10.1) |

10.7 (−11.8) |

16.3 (−8.7) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 17.24 (438) |

13.05 (331) |

13.90 (353) |

10.94 (278) |

7.40 (188) |

5.60 (142) |

1.34 (34) |

1.77 (45) |

4.52 (115) |

10.64 (270) |

16.74 (425) |

18.63 (473) |

121.77 (3,092) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[69] | |||||||||||||

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mount Hood Highest Point". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ↑ "Mount Hood, Oregon". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2011-06-04.

- ↑ "Mount Hood–History and Hazards of Oregon's Most Recently Active Volcano". U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 060-00. U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Forest Service. 2005-06-13. Archived from the original on 2018-08-22. Retrieved 2007-01-16.

- ↑ "Hood". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- ↑ "Glaciers of Oregon". Glaciers of the American West. Archived from the original on 2010-10-03. Retrieved 2007-02-24. quoting McNeil, Fred H. (1937). Wy'east the Mountain, A Chronicle of Mount Hood. Hillsboro, Oregon: Metropolitan Press. OCLC 191334118.

- 1 2 3 "How High is Hood" (editorial). The Register-Guard. Eugene, Oregon. 1993-09-14. p. A8. Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- 1 2 3 Helman, Adam (2005). "Table of United States Peaks by Spire Measure". The Finest Peaks: Prominence and Other Mountain Measures. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing. p. 114. ISBN 9781412059947. OCLC 71147989.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Swanson, D.A.; et al. (1989). "Mount Hood, Oregon". Cenozoic Volcanism in the Cascade Range and Columbia Plateau, Southern Washington and Northernmost Oregon: AGU Field Trip Guidebook T106, July 3–8, 1989. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 1999-02-03. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ↑ Most likely to erupt based on history; see James S. Aber. "Volcanism of the Cascade Mountains". GO 326/ES 767. Emporia State University. Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ↑ Scott, W.E.; Pierson, T.C.; Schilling, S.P.; Costa, J.E.; Gardner, C.A.; Vallance, J.W.; Major, J.J. (1997). "Volcano Hazards in the Mount Hood Region, Oregon". Open-File Report 97-89. U.S. Geological Survey, Cascades Volcano Observatory. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02.

- ↑ "National Historic Landmarks Program—Timberline Lodge". National Historic Register. National Park Service. 1977-12-22. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ↑ Guido, Marc (2006-07-17). "Beat the Heat: Summer Skiing on Oregon's Mount Hood". FastTracks Online Ski Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ "July 2020". WyEast Blog. Retrieved 2021-06-06.

- ↑ "About the Forest". U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original on 2013-07-25. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ↑ "Trail Stewardship". U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original on 2014-11-04. Retrieved 2014-06-13.

- ↑ Mussulman, Joseph (September 2011). "Lolo in Trade Jargon". Discovering Lewis & Clark. The Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation. p. 12. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- ↑ Matarrese, Andy (June 11, 2017). "Anthropologist dispelling myths with plankhouse talk". The Columbian. Archived from the original on 2020-10-05. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- ↑ Lewis, David G. (13 May 2018). "Native Place Names". Quartux. Archived from the original on 2020-09-24. Retrieved 2020-06-01.

- ↑ Balch, Frederic Homer (1890). "The Bridge of the Gods". Internet Archive. A.C.McClurg and Company. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ Topinka, Lyn (2008-05-21). "Naming the Cascade Range Volcanoes: Mount Adams, Washington". Volcanoes and History. Cascades Volcano Observatory (CVO). Archived from the original on 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2015-06-14.

- ↑ Clark, Ella E. (1953). Indian Legends of the Pacific Northwest. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23926-1. OCLC 51779712.

- 1 2 Grauer, p. 9

- ↑ Topinka, Lyn (2004-06-29). "The Volcanoes of Lewis and Clark – October 1805 to June 1806: Introduction". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2013-02-24. Retrieved 2013-07-17.

- ↑ "USS Mount Hood (AE-11), 1944–1944". Department of the Navy – Naval Historical Center. Archived from the original on 2008-03-04. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ↑ "Mount Hood (AE 29)". Naval Vessel Register. U.S. Navy. Retrieved 2013-07-11.

- 1 2 "Volcano Information: Mount Hood". U.S. Geological Survey. 2008-06-02. Archived from the original on 2013-02-22. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 Crandell, Dwight R. (1980). "Recent Eruptive History of Mount Hood, Oregon, and Potential Hazards from Future Eruptions". Geological Survey Bulletin. U.S. Geological Survey (1492): 1, 7–8, 43–45. doi:10.3133/b1492. Archived from the original on 2012-09-22. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ Brantley, Steven R.; Scott, William E. "The Danger of Collapsing Lava Domes: Lessons for Mount Hood, Oregon". Earthquakes & Volcanoes, v. 24, n. 6, pp. 244–269. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2013-07-18.

- ↑ "Hood: Latest Activity Reports". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2007-06-22.

- ↑ "Cascade Range Current Update for June 29, 2002". U.S. Geological Survey. 2002-06-29. Archived from the original on 2013-09-04.

- ↑ "Current Alerts for U.S. Volcanoes: Cascade Range Volcanoes". U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2013-07-28. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ "Oregon Volcanoes: Mt. Hood Volcano". U.S. Forest Service. 2003-12-24. Archived from the original on 2011-05-12.

- ↑ Shannon Hall (September 9, 2019). "We're Barely Listening to the U.S.'s Most Dangerous Volcanoes—A thicket of red tape and regulations have made it difficult for volcanologists to build monitoring stations along Mount Hood and other active volcanoes". The New York Times. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- ↑ "Three new monitoring stations installed at Mount Hood". November 13, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grauer, Jack (July 1975). Mount Hood: A Complete History. self-published. pp. 199, 291–292. OCLC 1849244.

- ↑ Mitchell, Samuel Augustus (1857). "Mitchell's School atlas: comprising the maps and tables designed to accompany Mitchell's School and family geography" (PDF). Philadelphia: H. Cowperthwait & Company. p. 8. nrlf_ucb:GLAD-83976101. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ↑ "Mount Hood National Forest". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ↑ Morris, Mark (2007). "Columbia River Gorge and Mount Hood". Moon Oregon (Seventh ed.). Emeryville, California: Avalon Travel. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-56691-930-2. OCLC 74524856. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Gutman, Bill; Frederick, Shawn (2003). Being Extreme: Thrills and Dangers in the World of High-risk Sports (Illustrated ed.). New York, New York: Citadel Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-8065-2354-5. OCLC 54525467. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Palmerlee, Danny (2009). Pacific Northwest Trips (Illustrated ed.). Oakland, California: Lonely Planet. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-74179-732-9. OCLC 244420587. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Marbach, Peter; Cook, Janet (2005). Mount Hood: The Heart of Oregon (Illustrated ed.). Portland, Oregon: Graphic Arts Center Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-55868-923-7. OCLC 60839414. Archived from the original on 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ DeBenedetti, Christian (March 2005). "Cliff Hanger". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. 182 (3): 136. ISSN 0032-4558. Archived from the original on 2017-02-07. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Bernstein, Art (2003). Oregon Byways: 75 Scenic Drives in the Cascades and Siskiyous, Canyons and Coast. Berkeley, California: Wilderness Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-89997-277-0. OCLC 53021936. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Roadtripping USA: The Complete Coast-to-Coast Guide to America. Let's Go (Third ed.). New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. 2009. p. 340. ISBN 978-0-312-38583-5. OCLC 243544813. Archived from the original on 2014-06-28. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Pluth, Tanya (2009). "Climbers Stranded on Mount Hood". climbing.com (Skram Media). Archived from the original on 2014-03-08.

- ↑ "Glaciers of Oregon: Glaciated Regions". Glaciers of the American West. Portland State University. Archived from the original on 2010-10-03. Retrieved 2013-07-13.

- ↑ "USGS Mount Hood North (OR) Topo". TopoQuest. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ Ostertag, George (2007). Levanthal, Josh (ed.). Our Oregon. St. Paul, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-2921-4. OCLC 74459023.

- 1 2 3 Driedger, Carolyn L.; Kennard, Paul M. (1986). "Ice Volumes on Cascade Volcanoes: Mount Rainier, Mount Hood, Three Sisters and Mount Shasta". Geological Survey Professional Paper. U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ↑ Jackson, Keith M.; Fountain, Andrew G. (2007). "Spatial and morphologic change on Eliot Glacier, Mount Hood, Oregon, USA". Annals of Glaciology. 46 (1): 222–226. Bibcode:2007AnGla..46..222J. doi:10.3189/172756407782871152.

- ↑ Driedger, Carolyn L.; Kennard, Paul M. (1986). "Ice Volumes on Cascade Volcanoes: Mount Rainier, Mount Hood, Three Sisters and Mount Shasta" (PDF). Geological Survey Professional Paper 1365. USGS. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ↑ "Glaciers in Hood River County". Geographic Names Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ↑ "Glaciers in Clackamas County". Geographic Names Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ↑ "Mt Hood National Forest". USDA Forest Service.

- ↑ "Timberline National Historic Trail #600". U.S. Forest Service. Archived from the original on 2015-01-03. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ Cook, Greg. "Weekend Backpacker: Portland". GORP. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2014-07-28. Retrieved 2013-09-15.

- ↑ USDA Forest Service (1921). Oregon Skyline Trail. Portland: The Oregon Tourist and Information Bureau.

- ↑ Green, Aimee; Larabee, Mark; Muldoon, Katy (2007-02-19). "Everything goes right in Mount Hood search". The Oregonian. Portland, Oregon. Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ↑ ""Mount Hood Pearly Gates" GetHighOnAltitude.com". Get High on Altitude. 16 January 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2019-04-12.

- ↑ "Mount Hood Summit". USDA Forest Service. Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

- ↑ "Mount Hood". SummitPost. 2010-06-09. Archived from the original on 2012-11-07. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ↑ "Portland, OR: Mount Hood via the South Side Route". Backpacker Magazine. Trimble Outdoors. 2008-05-12. Archived from the original on 2012-04-06. Retrieved 2011-11-27.

- ↑ "Climbing Mount Hood: Southside Climbing Conditions – June 9, 2007". United States Forest Service. Archived from the original on 2007-06-14.

- ↑ Holguin, Jaime (2002-05-30). "Last Body Recovered From Mount Hood". CBS News. Archived from the original on 2014-03-10. Retrieved 2014-03-09.

- ↑ "Mount Hood National Forest Technical Climbing". GORP.com. Archived from the original on 2010-05-13. Retrieved 2008-08-28.

- ↑ Jaquiss, Nigel (1999-10-13). "Without A Trace". Willamette Week. Portland, Oregon. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ↑ Keck, Kristi (2007-02-20). "Weighing the risks of climbing on Mount Hood". CNN. Archived from the original on 2007-03-02. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ↑ "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". prism.oregonstate.edu. Retrieved June 1, 2023.

- ↑ "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

To find the table data on the PRISM website, start by clicking Coordinates (under Location); copy Latitude and Longitude figures from top of table; click Zoom to location; click Precipitation, Minimum temp, Mean temp, Maximum temp; click 30-year normals, 1991-2020; click 800m; click Retrieve Time Series button.

External links

- "Mount Hood". The Oregon Encyclopedia

- "Mount Hood History". mounthoodhistory.com. Archived from the original on 2007-06-08. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- "Mount Hood: Climbing Oregon's Highest Peak". Oregon Field Guide.

- "Mt. Hood's Volcanic Past". Oregon Field Guide.

%252C_crop.jpg.webp)