Lucie Odier | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signature | |

|

Lucie Odier (7 September 1886, Geneva – 6 December 1984, Geneva) was a Swiss nurse from a Patrician family background. She became a leading expert at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) for relief actions to civilians. As only the fourth female member of the ICRC's governing body Odier helped to pave the way towards gender equality in the organisation which itself has historically been a pioneer of international humanitarian law.[1]

During the Second World War she became an outspoken advocate inside the ICRC leadership to publicly denounce Nazi Germany's system of extermination and concentration camps.[2][3]

After her resignation as a member for age reasons in 1961 she was appointed as the first female honorary vice-president of the ICRC.[4]

Life

Family background and education

On the paternal side, Odier hailed from a family of Huguenot background from Pont-en-Royans in the Dauphiné region of southeastern France, which was a center of Protestantism in the 16th century. When the 1598 Edict of Nantes, which had restored some civil rights to the Huguenots, was revoked by Louis XIV in 1685, some 20,000 Protestants fled from Dauphiné in the following years, amongst them Antoine Odier, Lucie's great-great-great-grandfather. As a teenager, he acquired the citizenship of the Republic of Geneva in 1714 where he started working as a merchant. Some of his descendants became politicians, amongst them Lucie's uncle Édouard Odier (1844-1919),[5] who was elected a member of the Council of States and of the National Council.[6]

Lucie's father was Albert Octave Odier (1845-1928), a civil engineer working first at the Western Switzerland railways[1] and then in a leading position at the municipality of Geneva.[7] There he was responsible for the reconstruction of a number of bridges linking the Île de Genève and the Île Rousseau in the middle of the Rhone, which are still landmarks today.[8][9] Lucie's mother Camille Jeanne Louise Chaponnière (1856-1927) came from Marseille, where Lucie's Genevan grandfather was a trader and judge at the commercial court.[10] Lucie was the fifth of the seven children that Albert and Camille had.[11] She was part of Geneva's patrician class which

«turned to banking and philanthropic activities at the end of the 19th century, after losing control of the major public offices».[12]

The Odier family played a particularly important role in Geneva's financial sector thanks to marriages with other Patrician families and especially since Charles Odier (1804–81) became associated with the bank Lombard, Bonna & Cie in 1830, which later became Lombard, Odier & Cie. However, numerous other members of the family became medical doctors and nurses.[5] While Lucie Odier attended Geneva's Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1911,[13] she subsequently followed in that medical tradition and obtained her nursing diploma in 1914[4] from the School of the Samaritans.[14]

World War I

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in July 1914, Lucie Odier upon the recommendation of the Genevan orthopedist Alfred Machard (not to be confused with the namesake French writer and actor)[14] started working in a leading position as a nurse in the military hospital Grand Cercle at Aix-les-Bains, a commune in the French department of Savoie, some 70 km south of Geneva. The auxiliary hospitals in the town not only provided care to French soldiers, but also to members of the U.S. Army.

In December 1914, she went back to Geneva to treat those who returned there with war injuries, since thousands of Swiss volunteers had joined the French army.[15] In addition, she tended to Prisoners of War, who were interned in Switzerland because they were either seriously ill or wounded or relatively old. She also took up tasks concerning the care for civilian refugees.[1] After the outbreak of the Spanish Flu, she dedicated herself to the care of its victims as well.[16]

Between the World Wars

In 1920, Odier was assigned to lead the social hygiene dispensary of Geneva's Red Cross section. It aimed to contain the spread of sexually transmissible diseases through sex education and the regulation of prostitution.[1] Odier also engaged in child welfare for the poorest groups of Geneva's population.[17] In addition, she led the visiting nurses service.[1][16]

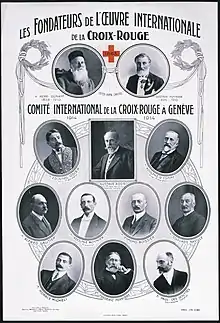

From these activities she was obviously drawn to the ICRC to follow in the footsteps of her uncle Édouard Odier. The jurist was one of its founding members, since he joined the organisation in 1874 barely a decade after its founding, eventually became vice-president of the ICRC and was also a personal friend of its president Gustave Ador:[6]

During the first phase of the Chinese Civil War (1927–1936), Odier directed the relief actions which the ICRC undertook in that conflict.[4]

In July 1929, she represented the ICRC at the congress of the International Council of Nurses – founded in 1899 as the first international organization for health care professionals and headquartered in Geneva – in Montreal.[1]

In early 1930, Odier was elected as a member of the ICRC.[4] She was only the fourth woman to be part of the governing body after Marguerite Frick-Cramer, Pauline Chaponnière-Chaix and Suzanne Ferrière.

In October 1934, Odier travelled along with Frick-Cramer and another fellow female ICRC-pioneer – Marguerite van Berchem – to Tokyo to represent the ICRC at the 15th international conference of the Red Cross Movement, where Frick-Cramer presented the draft text of a convention to grant civilian detainees at least the same protections as POWs. The conference accepted the recommendations and commissioned the ICRC to organise a diplomatic conference, which could not take place though due to objections from the British and French governments.[18]

Odier also became an active member of the Florence Nightingale Foundation, soon after it was founded in 1934 to provide post-graduate education to nurses in commemoration of Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), the English social reformer and founder of modern nursing.[4]

During the Fascist war of aggression of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935-1937) Odier was the only woman involved in the Ethiopia operations of the ICRC.[19] When it received information in April 1936 from the delegate and medical doctor Marcel Junod about the use of Italian chemical weapons in Korem, Odier was part of the group that pushed to denounce the chemical warfare publicly. She made preparations to do so, but at last the legalist faction of ICRC President Max Huber prevailed and only a «timid and excessively polite» letter was sent to the Italian Red Cross.[20]

A few days after the Anschluss – the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938 – Odier received from the exiled Austrian Princess Nora von Starhemberg, who was a Jewish actress and married to former Vice-Chancellor Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg, a list with the names of 49 missing and/or detained people. However, President Huber stopped all efforts by Odier and her colleague Suzanne Ferrière to request information about the disappeared from the German Red Cross.[18]

During the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), Odier directed all the relief actions which the ICRC undertook in that conflict,[4][17][21] working closely with Renée Bordier, who was likewise a nurse hailing from a prominent Patrician family of bankers (Bordier & Cie) and became the fifth-ever female ICRC-member in 1938.[1] In June of that year, Odier represented the ICRC at the 16th International Red Cross Conference in London,[4] where the two rival Spanish Red Cross Societies participated.[22]

World War II

At the beginning of the Second World War Odier set up the and led the relief bureau and subsequently the relief division.[4] In August 1940, Odier flew with Marcel Junod to London, risking their lives in the middle of the Battle of Britain.[16] There they toured for two weeks British camps for POWs and civilian detainees.[23] Upon her return she reported that the British authorities lost all confidence in the effective application of the Geneva conventions by their Axis adversaries.[24] Nevertheless, she managed to convince them to lift a blockade on foodstuffs destined to the POWs in Germany.[4] In December 1940, Odier and fellow ICRC member Martin Bodmer travelled to Berlin to discuss principal issues with the German Red Cross, the Foreign Office and the High Command of the Wehrmacht [25]

Odier was widely considered to belong to the idealists within the ICRC leadership who gradually lost influence vis-à-vis the "pragmatists".[26] The latter were led by Huber, who at the same time did private business in the arms industry.[27] In contrast, when it came to Odier,

«Her colleagues appreciated her humanitarian spirit, devotion, common sense, courage and tenacity. These qualities made her not an accommodating but a rather challenging member. Carl Jacob Burckhardt considered her as 'unintelligent and dangerously obstinate in delicate affairs'. [..] Odier courageously questioned several times a line of action which did not seem right to her, especially when legal considerations were overriding general humanitarian concerns.»[19]

According to the historian Jean-Claude Favez, Odier was one of the ICRC members who were informed in August / September 1942 by Gerhart Riegner, the Secretary of the World Jewish Congress in Geneva, about alarming reports on Nazi Germany's intention to mass murder the European Jews.[18][28] By autumn of that year, the ICRC leadership received more information about the systematic extermination of Jews by Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe, the so-called Final Solution. A large majority of the ICRC's about two dozen members at its general assembly on 14 October 1942 – especially its four female members Frick-Cramer, Odier, Ferrière, and Bordier – was in favour of a public protest.[18] Odier stated:

«if we do nothing, we will compromise our post-war activities, as our silence could be interpreted as acceptance»

However, Burckhardt – who went on to become the ICRC president in 1944 – and Switzerland's President Philipp Etter firmly denied that request. Odier later admitted that each member of the Committee suffered from this silence.[2] Subsequently, her standing inside the organisation was diminished: when the executive committee established a department for special assistance to civilian detainees, Odier as well as her fellow experts Ferrière and Frick-Cramer were left out of it.[18]

In early 1943, Odier and Ferrière conducted a joint mission to the Middle East and Africa to assess the situation of civilian detainees. Their tour of three months duration included stops in Istanbul, Ankara, Cairo, Jerusalem, Beirut, Johannesburg, Salisbury, and Nairobi.[29] In the same year she visited Berlin, when the German capital was subject to one of the first large-scale air raids by the allied forces.[17]

In late 1944, the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that it awarded the ICRC its second Nobel Peace Prize after 1917. As in World War I, it was the only recipient during the war years. While the then leadership of the ICRC was later sharply criticized for not publicly denouncing Nazi Germany, Odier all the more made her distinct contribution to what the Nobel Committee credited the ICRC with, i.e.

«the great work it has performed during the war on behalf of humanity.»

Post-WWII

Still in 1945, at the end of the Second World War, Odier went to Northern Italy to provide assistance to hospitals for taking care of returning refugees.[4] When thousands of former POWs and civilians, who had been taken to Germany as slave labourers, were caught in a sudden cold spell at the Brenner Pass while crossing the alps, Odier managed to organise a convoy with medical help for them.[17]

In the following years, she continued to focus on issues concerning the recruitment and training of nurses and of voluntary nursing auxiliaries as well as on medical equipment, including editing a number of publications in several languages. In addition, she extended her commitment to questions on the rehabilitation of disabled people.[16]

In August 1948, Odier represented the ICRC at the Seventeenth International Conference in Stockholm. Four years later, in July and August 1952, she participated in the Eighteenth International Red Cross Conference in Toronto. And

«She contributed much to strengthen the ICRC's links with nursing associations which looked upon her as a model and a guide.»[16]

In 1960, Odier received the gold medal of the ICRC as only the third person ever, after Huber and Jacques Cheneviére.[30] In the following year, she announced her resignation as a member of the ICRC for age reasons. She was subsequently elected not only as an honorary member of the ICRC but also as its honorary vice-president.[4]

In 1963, the ICRC received its third Nobel Peace Prize after 1917 and 1944, making it the only organisation to be honoured thrice. It may be argued that Odier contributed to this award as well.

Odier lived in Geneva's affluent Rue de l'Athénée until her eighties and then moved into the mansion of the Bern deaconesses in Presinge, a municipality in the rural northeastern part of the canton of Geneva.[14] When she died in her 99th year, the Journal de Genève called her the «grande dame» of the ICRC.[15] The International Review of the Red Cross wrote in its obituary:

«All who had the privilege of knowing and working with this great lady praised her dedication, perseverance, enthusiasm, unaffected manner and courage, and remember her with affection and gratitude.»[16]

On the occasion of the 100th birthday, the Journal de Genève published a tribute to Odier which stressed her «extreme humility».[31] Odier is buried in Cologny – one of the most affluent municipalities in the Canton of Geneva – where also other former ICRC colleagues like Gustave Ador and Gautier-van Berchem have their graves. Her gravestone bears a verse from 1 John 2:10:

CELUI QUI AIME SON FRÈRE DEMEURE DANS LA LUMIÈRE ("Whoever loves his brother remains in the light")

Selected works

- Some advice to nurses and other members of the medical services of the armed forces, Geneva 1951

- Medical personnel assigned to the care of the wounded and sick in the armed forces (training, duties, status and terms of enrolment), Geneva 1953

External links

- Correspondence between Lucie Odier and Carl Jacob Burckhardt - 17 letters written in French between 1941 and 1965 - from Burckhardt's bequest at the library of the University of Basel

- Lucie Odier in the Dodis data bank of the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Fiscalini, Diego (1985). Des élites au service d'une cause humanitaire : le Comité International de la Croix-Rouge (in French). Geneva: Université de Genève, faculté des lettres, département d'histoire. pp. 128, 225.

- 1 2 Vonèche Cardia, Isabelle (2015). "Les raisons du silence du Comité international de la Croix-Rouge (CICR) face aux déportations". Revue d'Histoire de la Shoah (in French). 203: 102, 106, 112. ISBN 9782916966120. ISSN 2111-885X.

- ↑ Steinacher, Gerald (2017). Humanitarians at War. The Red Cross in the Shadow of the Holocaust. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 9780198704935.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "RESIGNATION" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 1 (8): 442–443. November 1961. doi:10.1017/S0020860400013346. ISSN 1607-5889.

- 1 2 Vaj, Daniela (31 August 2009). "Odier". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- 1 2 Perrenoud, Marc (23 March 2009). "Odier, Edouard". Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS) (in German). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ Rossellat, Lionel. "Généalogie de Albert Octave Odier". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ "Genève, pont des Bergues et île Rousseau". Bibliothèque de Genève Iconographie (in French). Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ↑ "Genève, île Rousseau: nouvelle passerelle". Bibliothèque de Genève Iconographie (in French). Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ↑ Rossellat, Lionel. "Généalogie de Eugène Louis Chaponnière". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ Rossellat, Lionel. "Généalogie de Lucie Odier". Geneanet (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ Meyre, Camille (12 March 2020). "Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer". Cross-Files | ICRC Archives, audiovisual and library. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ↑ "Ecole des Beaux-Arts". La Tribune de Genève. 33 (151): 6. 30 June 1911 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- 1 2 3 H.V. (6 September 1976). "Lucie Odier a 90 ans". Journal de Genève (in French).

- 1 2 "NÉCROLOGIE: Mort de Lucie Odier grande dame du CICR". Journal de Genève (in French). 11 December 1984.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Death of Miss Lucie Odier" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross: 35–36. February 1985.

- 1 2 3 4 Fiedler-Winter, Rosemarie (1970). Engel brauchen harte Hände (in German). Gütersloh: Bertelsmann. pp. 291–308.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Favez, Jean-Claude (1999). The Red Cross and the Holocaust. Translated by Fletcher, John; Fletcher, Beryl. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–40, 48, 50, 88. ISBN 2735108384.

- 1 2 Baudendistel, Rainer (2006). Between Bombs and Good Intentions: The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and the Italo-Ethiopian war, 1935-1936. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 29, 98, 292. ISBN 9781845450359.

- ↑ Baudendistel, Rainer (March 1998). "Force versus law: The International Committee of the Red Cross and chemical warfare in the Italo-Ethiopian war 1935–1936" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. pp. 94–97. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ↑ Marqués Posty, Pierre (2000). La Croix-Rouge pendant la guerre d'Espagne (1936-1939) : les missionnaires de l'humanitaire (in French). Paris / Montréal: L'Harmattan. pp. 94–95, 379. ISBN 978-2-7384-8838-1.

- ↑ Bugnion, François (December 2009). "The International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent: challenges, key issues and achievements" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 91 (876): 687. doi:10.1017/S1816383110000147. S2CID 145686025.

- ↑ "The International Red Cross and our Prisoners in Germany". The British Journal of Nursing. 89–90: 98. 1941.

- ↑ Wylie, Neville (2010). Barbed Wire Diplomacy: Britain, Germany, and the Politics of Prisoners of War, 1939-1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0199547593.

- ↑ "Internationales Rotes Kreuz". Freiburger Nachrichten. 304: 3. 30 December 1940 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ↑ Bauerkämper, Arnd (2021). Sicherheit und Humanität im Ersten und Zweiten Weltkrieg: Der Umgang mit zivilen Feindstaatenangehörigen im Ausnahmezustand (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin / Boston: De Gruyter Oldenbourg. p. 987. ISBN 978-3-11-052995-1.

- ↑ Rauh, Cornelia (2009). Schweizer Aluminium für Hitlers Krieg? Zur Geschichte der "Alusuisse" 1918–1950 (in German). Munich: Beck. ISBN 9783406522017.

- ↑ Friedländer, Saul (2007). Das Dritte Reich und die Juden: die Jahre der Vernichtung 1939-1945 (in German). Munich: Beck. p. 843. ISBN 9783406566813.

- ↑ Odier, Lucie (September 1943). "Mission en Afrique" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 25 (297): 730–743. doi:10.1017/S1026881200015919. S2CID 145075925.

- ↑ "Mr. Carl J. Burckhardt receives the Gold Medal of the ICRC" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 1 (8): 444–447. November 1961. doi:10.1017/S0020860400013358. ISSN 0020-8604.

- ↑ B.R. (9 September 1986). "Hommage: Lucie Odier aurait eu 100 ans le 7 septembre". Journal de Genève (in French).