John Marshall | |

|---|---|

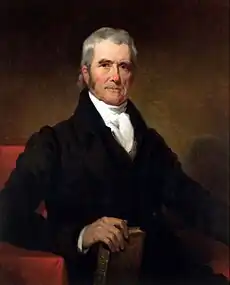

Portrait by Henry Inman, c. 1832 | |

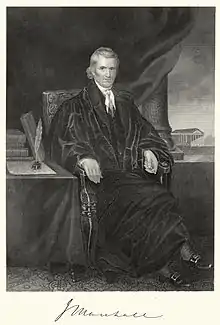

| 4th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office February 4, 1801 – July 6, 1835[1] | |

| Nominated by | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Oliver Ellsworth |

| Succeeded by | Roger B. Taney |

| 4th United States Secretary of State | |

| In office June 13, 1800 – March 4, 1801 | |

| President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Timothy Pickering |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia's 13th district | |

| In office March 5, 1799 – June 6, 1800 | |

| Preceded by | John Clopton |

| Succeeded by | Littleton Tazewell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | September 24, 1755 Germantown, Virginia Colony, British America |

| Died | July 6, 1835 (aged 79) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Shockoe Hill Cemetery |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse | Mary Willis Ambler |

| Children | 10, including Thomas and Edward |

| Education | College of William & Mary |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1775–1780 |

| Rank | Lieutenant Captain |

| Unit | 3rd Virginia Regiment (1775) 11th Virginia Regiment (1776-80) |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

John Marshall (September 24, 1755 – July 6, 1835) was an American statesman, lawyer, and Founding Father who served as the fourth chief justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longest serving justice in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court, and is widely regarded as one of the most influential justices ever to serve. Prior to joining the court, Marshall briefly served as both the U.S. secretary of state under President John Adams, and a representative, in the U.S. House of Representatives from Virginia, thereby making him one of the few Americans to serve on all three branches of the United States federal government.

Marshall was born in Germantown in the Colony of Virginia in 1755. After the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, he joined the Continental Army, serving in numerous battles. During the later stages of the war, he was admitted to the state bar and won election to the Virginia House of Delegates. Marshall favored the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, and he played a major role in Virginia's ratification of that document. At the request of President Adams, Marshall traveled to France in 1797 to help bring an end to attacks on American shipping. In what became known as the XYZ Affair, the government of France refused to open negotiations unless the United States agreed to pay bribes. After returning to the United States, Marshall won election to the U.S. House of Representatives and emerged as a leader of the Federalist Party in Congress. He was appointed secretary of state in 1800 after a cabinet shake-up, becoming an important figure in the Adams administration.

In 1801, Adams appointed Marshall to the Supreme Court. Marshall quickly emerged as the key figure on the court, due in large part to his personal influence with the other justices. Under his leadership, the court moved away from seriatim opinions, instead issuing a single majority opinion that elucidated a clear rule. The 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison presented the first major case heard by the Marshall Court. In his opinion for the court, Marshall upheld the principle of judicial review, whereby courts could strike down federal and state laws if they conflicted with the Constitution. Marshall's holding avoided direct conflict with the executive branch, which was led by Democratic-Republican President Thomas Jefferson. By establishing the principle of judicial review while avoiding an inter-branch confrontation, Marshall helped implement the principle of separation of powers and cement the position of the American judiciary as an independent and co-equal branch of government.

After 1803, many of the major decisions issued by the Marshall Court confirmed the supremacy of the federal government and the federal Constitution over the states. In Fletcher v. Peck and Dartmouth College v. Woodward, the court invalidated state actions because they violated the Contract Clause. The court's decision in McCulloch v. Maryland upheld the constitutionality of the Second Bank of the United States and established the principle that the states could not tax federal institutions. The cases of Martin v. Hunter's Lessee and Cohens v. Virginia established that the Supreme Court could hear appeals from state courts in both civil and criminal matters. Marshall's opinion in Gibbons v. Ogden established that the Commerce Clause bars states from restricting navigation. In the case of Worcester v. Georgia, Marshall held that the Georgia criminal statute that prohibited non-Native Americans from being present on Native American lands without a license from the state was unconstitutional. John Marshall died of natural causes in 1835, and Andrew Jackson appointed Roger Taney as his successor.

Early years (1755 to 1782)

Marshall was born on September 24, 1755, in a log cabin in Germantown,[2] a rural community on the Virginia frontier, near present-day Midland, Fauquier County. In the mid-1760s, the Marshalls moved northwest to the present-day site of Markham, Virginia.[3] His parents were Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith, the granddaughter of politician Thomas Randolph of Tuckahoe and a second cousin of U.S. President Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Marshall was employed in Fauquier County as a surveyor and land agent by Lord Fairfax, which provided him with a substantial income.[4] Nonetheless, John Marshall grew up in a two-room log cabin, which he shared with his parents and several siblings; Marshall was the oldest of fifteen siblings.[3] One of his younger brothers, James Markham Marshall, would briefly serve as a federal judge.

Marshall was a first cousin of U.S. Senator (Ky) Humphrey Marshall and first cousin, three times removed, of General of the Army George C. Marshall.[5][lower-alpha 1] He was also a distant cousin of Thomas Jefferson.[9]: 433

From a young age, Marshall was noted for his good humor and black eyes, which were "strong and penetrating, beaming with intelligence and good nature".[10] With the exception of one year of formal schooling, during which time he befriended future president James Monroe, Marshall did not receive a formal education. Encouraged by his parents, the young Marshall read widely, reading works such as William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England and Alexander Pope's An Essay on Man.[11] He was also tutored by the Reverend James Thomson, a recently ordained deacon from Glasgow, Scotland, who resided with the Marshall family in return for his room and board.[12] Marshall was especially influenced by his father, of whom he wrote, "to his care I am indebted for anything valuable which I may have acquired in my youth. He was my only intelligent companion; and was both a watchful parent and an affectionate friend."[13] Thomas Marshall prospered in his work as a surveyor, and in the 1770s he purchased an estate known as Oak Hill.[14]

After the 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord, Thomas and John Marshall volunteered for service in the 3rd Virginia Regiment.[15] In 1776, Marshall became a lieutenant in the 11th Virginia Regiment of the Continental Army.[16] During the American Revolutionary War, he served in several battles, including the Battle of Brandywine, and endured the winter at Valley Forge. After he was furloughed in 1780, Marshall began attending the College of William and Mary.[17] Marshall read law under the famous Chancellor George Wythe at the College of William and Mary, and he was admitted to the state bar in 1780.[18] After briefly rejoining the Continental Army, Marshall won election to the Virginia House of Delegates in early 1782.[19]

Early political career (1782 to 1797)

Upon joining the House of Delegates, Marshall aligned himself with members of the conservative Tidewater establishment such as James Monroe and Richard Henry Lee. With the backing of his influential father-in-law, Marshall was elected to the Council of State, becoming the youngest individual up to that point to serve on the council.[20] In 1785, Marshall took up the additional office of Recorder of the Richmond City Hustings Court.[21] Meanwhile, Marshall sought to build up his own legal practice, a difficult proposition during a time of economic recession. In 1786, he purchased the law practice of his cousin, Edmund Randolph, after the latter was elected Governor of Virginia. Marshall gained a reputation as a talented attorney practicing in the state capital of Richmond, and he took on a wide array of cases. He represented the heirs of Lord Fairfax in Hite v. Fairfax (1786), an important case involving a large tract of land in the Northern Neck of Virginia.[22]

Under the Articles of Confederation, the United States during the 1780s was a confederation of sovereign states with a weak national government that had little or no effective power to impose tariffs, regulate interstate commerce, or enforce laws.[23] Influenced by Shays' Rebellion and the powerlessness of the Congress of the Confederation, Marshall came to believe in the necessity of a new governing structure that would replace the powerless national government established by the Articles of Confederation.[24] He strongly favored ratification of the new constitution proposed by the Philadelphia Convention, as it provided for a much stronger federal government. Marshall was elected to the 1788 Virginia Ratifying Convention, where he worked with James Madison to convince other delegates to ratify the new constitution.[25] After a long debate, proponents of ratification emerged victorious, as the convention voted 89 to 79 to ratify the constitution.[26]

.jpg.webp)

After the United States ratified the Constitution, newly elected President George Washington nominated Marshall as the United States Attorney for Virginia. Though the nomination was confirmed by the Senate, Marshall declined the position, instead choosing to focus on his own law practice.[27] In the early 1790s, the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party emerged as the country was polarized by issues such as the French Revolutionary Wars and the power of the presidency and the federal government. Marshall aligned with the Federalists, and at Alexander Hamilton's request, he organized a Federalist movement in Virginia to counter the influence of Thomas Jefferson's Democratic-Republicans. Like most other Federalists, Marshall favored neutrality in foreign affairs, high tariffs, a strong executive, and a standing military.[28] In 1795, Washington asked Marshall to accept appointment as the United States Attorney General, but Marshall again declined the offer. He did, however, serve in a variety of roles for the state of Virginia during the 1790s, at one point acting as the state's interim Attorney General.[29]

In 1796, Marshall appeared before the Supreme Court of the United States in Ware v. Hylton, a case involving the validity of a Virginia law that provided for the confiscation of debts owed to British subjects. Marshall argued that the law was a legitimate exercise of the state's power, but the Supreme Court ruled against him, holding that the Treaty of Paris in combination with the Supremacy Clause of the Constitution required the collection, rather than confiscation, of such debts.[30] According to biographer Henry Flanders, Marshall's argument in Ware v. Hylton "elicited great admiration at the time of its delivery, and enlarged the circle of his reputation" despite his defeat in the case.[31]

Adams administration (1797 to 1801)

Diplomat

Vice President John Adams, a member of the Federalist Party, defeated Jefferson in the 1796 presidential election and sought to continue Washington's policy of neutrality in the French Revolutionary Wars. After Adams took office, France refused to meet with American envoys and began attacking American ships.[32] In 1797, Marshall accepted appointment to a three-member commission to France that also included Charles Cotesworth Pinckney and Elbridge Gerry.[33] The three envoys arrived in France in October 1797, but were granted only a fifteen-minute meeting with French Foreign Minister Talleyrand. After that meeting, the diplomats were met by three of Talleyrand's agents who refused to conduct diplomatic negotiations unless the United States paid enormous bribes to Talleyrand and to the Republic of France.[34] The Americans refused to negotiate on such terms, and Marshall and Pinckney eventually decided to return to the United States.[35] Marshall left France in April 1798 and arrived in the United States two months later, receiving a warm welcome by Federalist members of Congress.[36]

During his time in France, Marshall and the other commissioners had sent secret correspondence to Adams and Secretary of State Timothy Pickering. In April 1798, Congress passed a resolution demanding that the administration reveal the contents of the correspondence. A public outcry ensued when the Adams administration revealed that Talleyrand's agents had demanded bribes; the incident became known as the XYZ Affair.[37] In July 1798, shortly after Marshall's return, Congress imposed an embargo in France, marking the start of an undeclared naval war known as the Quasi-War.[38] Marshall supported most of the measures Congress adopted in the struggle against France, but he disapproved of the Alien and Sedition Acts, four separate laws designed to suppress dissent during the Quasi-War. Marshall published a letter to a local newspaper stating his belief that the laws would likely "create, unnecessarily, discontents and jealousies at a time when our very existence as a nation may depend on our union."[39]

Congressman and Secretary of State

After his return from France, Marshall wanted to resume his private practice of law, but in September 1798 former President Washington convinced him to challenge incumbent Democratic-Republican Congressman John Clopton of Virginia's 13th congressional district.[40] Although the Richmond area district favored the Democratic-Republican Party, Marshall won the race, in part due to his conduct during the XYZ Affair and in part due to the support of Patrick Henry.[41] During the campaign, Marshall declined appointment as an associate justice of the Supreme Court, and President Adams instead appointed Marshall's friend, Bushrod Washington.[42] After winning the election, Marshall was sworn into office when the 6th Congress convened in December 1799. He quickly emerged as a leader of the moderate faction of Federalists in Congress.[43] His most notable speech in Congress was related to the case of Thomas Nash (alias Jonathan Robbins), whom the government had extradited to Great Britain on charges of murder. Marshall defended the government's actions, arguing that nothing in the Constitution prevents the United States from extraditing one of its citizens.[41] His speech helped defeat a motion to censure President Adams for the extradition.[44]

In May 1800, President Adams nominated Marshall as Secretary of War, but the president quickly withdrew that nomination and instead nominated Marshall as Secretary of State. Marshall was confirmed by the Senate on May 13 and took office on June 6, 1800.[45] Marshall's appointment as Secretary of State was preceded by a split between Adams and Hamilton, the latter of whom led a faction of Federalists who favored declaring war on France. Adams fired Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, a Hamilton supporter, after Pickering tried to undermine peace negotiations with France.[46] Adams directed Marshall to bring an end to the Quasi-War and settle ongoing disputes with Britain, Spain, and the Barbary States. The position of Secretary of State also held a wide array of domestic responsibilities, including the deliverance of commissions of federal appointments and supervision of the construction of Washington, D.C.[47] In October 1800, the United States and France agreed to the Convention of 1800, which ended the Quasi-War and reestablished commercial relations with France.[48]

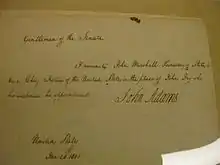

Nomination as Chief Justice

With the Federalists divided between Hamilton and Adams, the Democratic-Republicans emerged victorious in the presidential election of 1800.[49] However, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr both received 73 electoral votes, throwing the election to the Federalist-controlled House of Representatives.[lower-alpha 2] Hamilton asked Marshall to support Jefferson, but Marshall declined to support either candidate.[50]

In the contingent election held to decide whether Jefferson or Burr would become president, each state delegation had a single vote. Under this rule, it turned out that neither party had a majority because some states had split delegations. Over the course of seven days, February 11–17, 1801, the House cast a total of 35 ballots, with Jefferson receiving the votes of eight state delegations each time, one short of the necessary majority of nine. On February 17, on the 36th ballot, Jefferson was elected as president. Burr became vice president.[51] Had the deadlock lasted a couple weeks longer (through March 4 or beyond), Marshall, as Secretary of State, would have become acting president until a choice was made.[52]

After the election, Adams and the lame duck Congress passed what came to be known as the Midnight Judges Act. This legislation made sweeping changes to the federal judiciary, including a reduction in Supreme Court justices from six to five (upon the next vacancy in the court) so as to deny Jefferson an appointment until two vacancies occurred.[53]

In late 1800, Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth resigned due to poor health. Adams nominated former Chief Justice John Jay to once again lead the Supreme Court, but Jay rejected the appointment, partly due to his frustration at the relative lack of power possessed by the judicial branch of the federal government.[54] Jay's letter of rejection arrived on January 20, 1801, less than two months before Jefferson would take office.[55] Upon learning of Jay's rejection, Marshall suggested that Adams elevate Associate Justice William Paterson to chief justice, but Adams rejected the suggestion, instead saying to Marshall, "I believe I must nominate you."[56]

The Senate at first delayed confirming Marshall, as many senators hoped that Adams would choose a different individual to serve as chief justice. According to New Jersey Senator Jonathan Dayton, the Senate finally relented "lest another not so qualified, and more disgusting to the bench, should be substituted, and because it appeared that this gentleman [Marshall] was not privy to his own nomination".[57] Marshall was confirmed by the Senate on January 27, 1801, and took office on February 4. At the request of the president, he continued to serve as Secretary of State until Adams' term expired on March 4.[58] Consequently, Marshall was charged with delivering judicial commissions to the individuals who had been appointed to the positions created by the Midnight Judges Act.[59] Adams would later state that "my gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life."[60]

Chief Justice (1801 to 1835)

The Marshall Court convened for the first time on February 2, 1801, in the Supreme Court Chamber of the Capitol Building. The Court at that time consisted of Chief Justice Marshall and Associate Justices William Cushing, William Paterson, Samuel Chase, Bushrod Washington, and Alfred Moore, each of whom had been appointed by President Washington or President Adams.[61] Prior to 1801, the Supreme Court had been seen as a relatively insignificant institution. Most legal disputes were resolved in state, rather than federal courts. The Court had issued just 63 decisions in its first decades, few of which had made a significant impact, and it had never struck down a federal or state law.[62] During Marshall's 34-year tenure as Chief Justice, the Supreme Court would emerge as an important force in the federal government for the first time, and Marshall himself played a major role in shaping the nation's understanding of constitutional law. The Marshall Court would issue more than 1000 decisions, about half of which were written by Marshall himself.[63] Marshall's leadership of the Supreme Court ensured that the federal government would exercise relatively strong powers, despite the political domination of the Democratic-Republicans after 1800.[64]

Personality, principles, and leadership

Soon after becoming chief justice, Marshall changed the manner in which the Supreme Court announced its decisions. Previously, each Justice would author a separate opinion (known as a seriatim opinion) as was done in the Virginia Supreme Court of his day and is still done today in the United Kingdom and Australia. Under Marshall, however, the Supreme Court adopted the practice of handing down a single majority opinion of the Court, allowing it to present a clear rule.[65] The Court met in Washington only two months a year, from the first Monday in February through the second or third week in March. Six months of the year the justices were doing circuit duty in the various states. When the Court was in session in Washington, the justices boarded together in the same rooming house, avoided outside socializing, and discussed each case intently among themselves. Decisions were quickly made, usually in a matter of days. The justices did not have clerks, so they listened closely to the oral arguments, and decided among themselves what the decision should be.[66]

Marshall's opinions were workmanlike and not especially eloquent or subtle. His influence on learned men of the law came from the charismatic force of his personality and his ability to seize upon the key elements of a case and make highly persuasive arguments.[67][68][69] As Oliver Wolcott observed when both he and Marshall served in the Adams administration, Marshall had the knack of "putting his own ideas into the minds of others, unconsciously to them".[70] By 1811, Justices appointed by a Democratic-Republican president had a 5-to-2 majority on the Court, but Marshall retained ideological and personal leadership of the Court.[71] Marshall regularly curbed his own viewpoints, preferring to arrive at decisions by consensus.[72] Only once did he find himself on the losing side in a constitutional case. In that case—Ogden v. Saunders in 1827—Marshall set forth his general principles of constitutional interpretation:[73]

To say that the intention of the instrument must prevail; that this intention must be collected from its words; that its words are to be understood in that sense in which they are generally used by those for whom the instrument was intended; that its provisions are neither to be restricted into insignificance, nor extended to objects not comprehended in them, nor contemplated by its framers—is to repeat what has been already said more at large, and is all that can be necessary.[73]

While Marshall was attentive when listening to oral arguments and often persuaded other justices to adopt his interpretation of the law, he was not widely read in the law, and seldom cited precedents. After the Court came to a decision, he would usually write it up himself. Often he asked Justice Joseph Story, a renowned legal scholar, to do the chores of locating the precedents, saying, "There, Story; that is the law of this case; now go and find the authorities."[74]

Jefferson administration

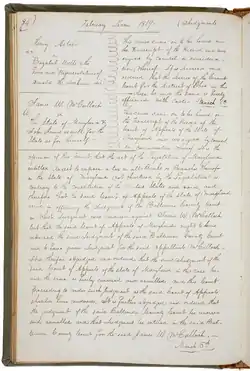

Marbury v. Madison

In his role as Secretary of State in the Adams administration, Marshall had failed to deliver commissions to 42 federal justices of the peace before the end of Adams's term. After coming to power, the Jefferson administration refused to deliver about half of these outstanding commissions, effectively preventing those individuals from receiving their appointments even though the Senate had confirmed their nominations. Though the position of justice of the peace was a relatively powerless and low-paying office, one individual whose commission was not delivered, William Marbury, decided to mount a legal challenge against the Jefferson administration. Seeking to have his judicial commission delivered, Marbury filed suit against the sitting Secretary of State, James Madison. The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case of Marbury v. Madison in its 1803 term. Meanwhile, the Democratic-Republicans passed the Judiciary Act of 1802, which effectively repealed the Midnight Judges Act and canceled the Supreme Court's 1802 term.[75][lower-alpha 3] They also began impeachment proceedings against federal judge John Pickering, a prominent Federalist; in response, Federalist members of Congress accused the Democratic-Republicans of trying to infringe on the independence of the federal judiciary.[77]

In early February 1803, the Supreme Court held a four-day trial for the case of Marbury v. Madison, though the defendant, James Madison, refused to appear.[78] On February 24, the Supreme Court announced its decision, which biographer Joel Richard Paul describes as "the single most significant constitutional decision issued by any court in American history." The Court held that Madison was legally bound to deliver Marbury's commission, and that Marbury had the right to sue Madison. Yet the Court also held that it could not order Madison to deliver the commission because the Judiciary Act of 1789 had unconstitutionally expanded the Court's original jurisdiction to include writs of mandamus, a type of court order that commands a government official to perform an act they are legally required to perform. Because that portion of the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional, the Court held that it did not have original jurisdiction over the case even while simultaneously holding that Madison had violated the law.[79]

Marbury v. Madison was the first case in which the Supreme Court struck down a federal law as unconstitutional and it is most significant for its role in establishing the Supreme Court's power of judicial review, or the power to invalidate laws as unconstitutional. As Marshall put it, "it is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is."[80] By asserting the power of judicial review in a holding that did not require the Jefferson administration to take action, the Court upheld its own powers without coming into direct conflict with a hostile executive branch that likely would not have complied with a court order.[81] Historians mostly agree that the framers of the Constitution did plan for the Supreme Court to have some sort of judicial review, but Marshall made their goals operational.[82] Though many Democratic-Republicans expected a constitutional crisis to arise after the Supreme Court asserted its power of judicial review, the Court upheld the repeal of the Midnight Judges Act in the 1803 case of Stuart v. Laird.[83][lower-alpha 4]

Impeachment of Samuel Chase

In 1804, the House of Representatives impeached Associate Justice Samuel Chase, alleging that he had shown political bias in his judicial conduct. Many Democratic-Republicans saw the impeachment as a way to intimidate federal judges, many of whom were members of the Federalist Party.[84] As a witness in the Senate's impeachment trial, Marshall defended Chase's actions.[85] In March 1805, the Senate voted to acquit Chase, as several Democratic-Republican senators joined with their Federalist colleagues in refusing to remove Chase.[86] The acquittal helped further establish the independence of the federal judiciary.[87][86] Relations between the Supreme Court and the executive branch improved after 1805, and several proposals to alter the Supreme Court or strip it of jurisdiction were defeated in Congress.[88]

Burr conspiracy trial

Vice President Aaron Burr was not renominated by his party in the 1804 presidential election and his term as vice president ended in 1805. After leaving office, Burr traveled to the western United States, where he may have entertained plans to establish an independent republic from Mexican or American territories.[89] In 1807, Burr was arrested and charged for treason, and Marshall presided over the subsequent trial. Marshall required Jefferson to turn over his correspondence with General James Wilkinson; Jefferson decided to release the documents, but argued that he was not compelled to do so under the doctrine of executive privilege.[90] During the trial, Marshall ruled that much of the evidence that the government had amassed against Burr was inadmissible; biographer Joel Richard Paul states that Marshall effectively "directed the jury to acquit Burr." After Burr was acquitted, Democratic-Republicans, including President Jefferson, attacked Marshall for his role in the trial.[91]

Fletcher v. Peck

In 1795, the state of Georgia had sold much of its western lands to a speculative land company, which then resold much of that land to other speculators, termed "New Yazooists." After a public outcry over the sale, which was achieved through bribery, Georgia rescinded the sale and offered to refund the original purchase price to the New Yazooists. Many of the New Yazooists had paid far more than the original purchase price, and they rejected Georgia's revocation of the sale. Jefferson tried to arrange a compromise by having the federal government purchase the land from Georgia and compensate the New Yazooists, but Congressman John Randolph defeated the compensation bill. The issue remained unresolved, and a case involving the land finally reached the Supreme Court through the 1810 case of Fletcher v. Peck.[92] In March 1810, the Court handed down its unanimous holding, which voided Georgia's repeal of the purchase on the basis of the Constitution's Contract Clause. The Court's ruling held that the original sale of land constituted a contract with the purchasers, and the Contract Clause prohibits states from "impairing the obligations of contracts."[93] Fletcher v. Peck was the first case in which the Supreme Court ruled a state law unconstitutional, though in 1796 the Court had voided a state law as conflicting with the combination of the Constitution together with a treaty.[94]

McCulloch v. Maryland

In 1816, Congress established the Second Bank of the United States ("national bank") in order to regulate the country's money supply and provide loans to the federal government and businesses. The state of Maryland imposed a tax on the national bank, but James McCulloch, the manager of the national bank's branch in Baltimore, refused to pay the tax. After he was convicted by Maryland's court system, McCulloch appealed to the Supreme Court, and the Court heard the case of McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819. In that case, the state of Maryland challenged the constitutionality of the national bank and asserted that it had the right to tax the national bank.[95] Writing for the Court, Marshall held that Congress had the power to charter the national bank.[96] He laid down the basic theory of implied powers under a written Constitution; intended, as he said "to endure for ages to come, and, consequently, to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs ...." Marshall envisaged a federal government which, although governed by timeless principles, possessed the powers "on which the welfare of a nation essentially depends."[97] "Let the end be legitimate," Marshall wrote, "let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited but consist with the letter and the spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional."[98]

The Court also held that Maryland could not tax the national bank, asserting that the power to tax is equivalent to "the power to destroy." The Court's decision in McCulloch was, according to Joel Richard Paul, "probably the most controversial decision" handed down by the Marshall Court. Southerners, including Virginia judge Spencer Roane, attacked the decision as an overreach of federal power.[99] In a subsequent case, Osborn v. Bank of the United States, the Court ordered a state official to return seized funds to the national bank. The Osborn case established that the Eleventh Amendment does not grant state officials sovereign immunity when they resist a federal court order.[100]

Cohens v. Virginia

Congress established a lottery in the District of Columbia in 1812, and in 1820 two individuals were convicted in Virginia for violating a state law that prohibited selling out-of-state lottery tickets. The defendants, Philip and Mendes Cohen, appealed to the Supreme Court. The Court's subsequent decision in the 1821 case of Cohens v. Virginia established that the Supreme Court could hear appeals from state courts in criminal lawsuits.[lower-alpha 5] The Court held that, because Virginia had brought the suit against the defendants, the Eleventh Amendment did not prohibit the case from appearing in federal court.[101]

Gibbons v. Ogden

In 1808, Robert R. Livingston and Robert Fulton secured a monopoly from the state of New York for the navigation of steamboats in state waters. Fulton granted a license to Aaron Ogden and Thomas Gibbons to operate steamboats in New York, but the partnership between Ogden and Gibbons collapsed. Gibbons continued to operate steamboats in New York after receiving a federal license to operate steamboats in the waters of any state. In response, Ogden won a judgment in state court that ordered Gibbons to cease operations in the state. Gibbons appealed to the Supreme Court, which heard the case of Gibbons v. Ogden in 1824. Representing Gibbons, Congressman Daniel Webster and Attorney General William Wirt (acting in a non-governmental capacity) argued that Congress had the exclusive power to regulate commerce, while Ogden's attorneys contended that the Constitution did not prohibit states from restricting navigation.[102]

Writing for the Court, Marshall held that navigation constituted a form of commerce and thus could be regulated by Congress. Because New York's monopoly conflicted with a properly issued federal license, the Court struck down the monopoly. However, Marshall did not adopt Webster's argument that Congress had the sole power to regulate commerce.[103] Newspapers in both the Northern states and the Southern states hailed the decision as a blow against monopolies and the restraint of trade.[104]

Jackson administration

Marshall personally opposed the presidential candidacy of Andrew Jackson, whom the Chief Justice saw as a dangerous demagogue, and he caused a minor incident during the 1828 presidential campaign when he criticized Jackson's attacks on President John Quincy Adams.[105] After the death of Associate Justice Washington in 1829, Marshall was the last remaining original member of the Marshall Court, and his influence declined as new justices joined the Court.[106] After Jackson took office in 1829, he clashed with the Supreme Court, especially with regards to his administration's policy of Indian removal.[107]

In the 1823 case of Johnson v. McIntosh, the Marshall Court had established the supremacy of the federal government in dealing with Native American tribes.[108] In the late 1820s, the state of Georgia stepped up efforts to assert its control over the Cherokee within state borders, with the ultimate goal of removing the Cherokee from the state. After Georgia passed a law that voided Cherokee laws and denied several rights to the Native Americans, former Attorney General William Wirt sought an injunction to prevent Georgia from exercising sovereignty over the Cherokee. The Supreme Court heard the resulting case of Cherokee Nation v. Georgia in 1831.[109] Writing for the Court, Marshall held that Native American tribes constituted "domestic dependent nations," a new legal status, but he dismissed the case on the basis of standing.[110]

At roughly the same time that the Supreme Court issued its decision in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, a group of white missionaries living with the Cherokee were arrested by the state of Georgia. The State did so on the basis of an 1830 state law that prohibited white men from living on Native American land without a state license. Among those arrested was Samuel Worcester, who, after being convicted of violating the state law, challenged the constitutionality of the law in federal court. The arrest of the missionaries became a key issue in the 1832 presidential election, and one of the presidential candidates, William Wirt, served as the attorney for the missionaries.[111] On March 3, 1832, Marshall delivered the opinion of the Court in the case of Worcester v. Georgia. The Court's holding overturned the conviction and the state law, holding that the state of Georgia had improperly exercised control over the Cherokee.[112] It is often reported that in response to the Worcester decision President Andrew Jackson declared "John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" More reputable sources recognize this as a false quotation.[113] Regardless, Jackson refused to enforce the decision, and Georgia refused to release the missionaries. The situation was finally resolved when the Jackson administration privately convinced Governor Wilson Lumpkin to pardon the missionaries.[114]

Other key cases

Marshall established the Charming Betsy principle, a rule of statutory interpretation, in the 1804 case of Murray v. The Charming Betsy. The Charming Betsy principle holds that "an act of Congress ought never to be construed to violate the law of nations if any other possible construction remains."[115] In Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, the Supreme Court held that it had the power to hear appeals from state supreme courts when a federal issue was involved. Marshall recused himself from the case because it stemmed from a dispute over Lord Fairfax's former lands, which Marshall had a financial interest in.[116] In Dartmouth College v. Woodward, the Court held that the protections of the Contract Clause apply to private corporations.[117] In Ogden v. Saunders, Marshall dissented in part and "assented" in part, and the Court upheld a state law that allowed individuals to file bankruptcy. In his separate opinion, Marshall argued that the state bankruptcy law violated the Contract Clause.[118] In Barron v. Baltimore, the Court held that the Bill of Rights was intended to apply only to the federal government, and not to the states.[119] The courts have since incorporated most of the Bill of Rights with respect to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, which was ratified decades after Marshall's death.

Authorship of Washington biography

After his appointment to the Supreme Court, Marshall began working on a biography of George Washington. He did so at the request of his close friend, Associate Justice Bushrod Washington, who had inherited the papers of his uncle. Marshall's The Life of George Washington, the first biography about a U.S. president ever published, spanned five volumes and just under one thousand pages. The first two volumes, published in 1804, were poorly received and seen by many as an attack on the Democratic-Republican Party.[120] Nonetheless, historians have often praised the accuracy and well-reasoned judgments of Marshall's biography, while noting his frequent paraphrases of published sources such as William Gordon's 1801 history of the Revolution and the British Annual Register.[121] After completing the revision to his biography of Washington, Marshall prepared an abridgment. In 1833 he wrote, "I have at length completed an abridgment of the Life of Washington for the use of schools. I have endeavored to compress it as much as possible. ... After striking out every thing which in my judgment could be properly excluded the volume will contain at least 400 pages."[122] The Abridgment was not published until 1838, three years after Marshall died.[123]

1829–1830 Virginia Constitutional Convention

In 1828, Marshall presided over a convention to promote internal improvements in Virginia. The following year, Marshall was a delegate to the state constitutional convention of 1829–30, where he was again joined by fellow American statesman and loyal Virginians, James Madison and James Monroe, although all were quite old by that time (Madison was 78, Monroe 71, and Marshall 74). Although proposals to reduce the power of the Tidewater region's slave-owning aristocrats compared to growing western population proved controversial,[124] Marshall mainly spoke to promote the necessity of an independent judiciary.

Death

.jpg.webp)

In 1831, the 76-year-old chief justice traveled to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he underwent an operation to remove bladder stones. That December, his wife, Polly, died in Richmond.[125] In early 1835, Marshall again traveled to Philadelphia for medical treatment, where he died on July 6, 1835, at the age of 79, having served as Chief Justice for over 34 years.[126] The Liberty Bell was rung following his death—a widespread story claims that this was when the bell cracked, never to be rung again.[127]

Unbeknownst to Marshall, his eldest son, Thomas, had died only a few days before, killed by the collapse of a chimney during a storm in Baltimore, through which he was passing on his way to be at his dying father's side.[128]

Marshall's body was returned to Richmond and buried next to Polly's in Shockoe Hill Cemetery.[129] The inscription on his tombstone, engraved exactly as he had wished, reads as follows:

Son of Thomas and Mary Marshall

was born September 24, 1755

Intermarried with Mary Willis Ambler

January 3, 1783

Departed this life

the 6th day of July 1835[125]

Marshall was among the last remaining Founding Fathers (a group poetically called the "Last of the Romans"),[130] the last surviving Cabinet member from the John Adams administration and the last Cabinet member to have served in the 18th century. In December 1835, President Andrew Jackson nominated Roger Taney to fill the vacancy for chief justice.[131]

Slavery

Over the course of his life, Marshall owned hundreds of slaves. During his most influential period as chief justice, through the mid-1820s, he wrote nearly every decision on slavery, creating a jurisprudence that was contemptuous of free blacks and favorable to violators of the federal ban on the African slave trade.[132] Marshall's association with slavery began early. In 1783, his father Thomas Marshall as a wedding present gave John Marshall his first slave, Robin Spurlock, who would remain Marshall's manservant as well as run his Richmond household. Upon Marshall's death, Spurlock would receive a now-seemingly cruel choice of accepting manumission on the condition of emigrating to another state or to Africa (at age 78 and leaving his still-enslaved daughter Agnes) or choosing his master/mistress from among Marshall's children.[133][134]

Early in his career, during the 1790s, Marshall represented slaves pro bono in a few cases, often trying to win the freedom of mixed-race individuals. In possibly his most famous anti-slavery case, Marshall represented Robert Pleasants, who sought to carry out his father's will and emancipate about ninety slaves; Marshall won the case in the Virginia High Court of Chancery, in an opinion written by his teacher George Wythe, but that court's holding was later restricted by the Virginia High Court of Appeals.[135] In 1796, Marshall also personally emancipated Peter, a black man he had purchased.[136] Furthermore, Marshall in 1822 signed an emancipation certificate for Jasper Graham, manumitted by the will of John Graham.[136]

After slave revolts early in the 19th century, Marshall expressed reservations about large-scale emancipation, in part because he feared that a large number of free blacks might rise up in revolution. Moreover, Virginia in 1806 passed a law requiring freed blacks to leave the state. Marshall instead favored sending free blacks to Africa. In 1817 Marshall joined the American Colonization Society (Associate Justice Bushrod Washington being its national President until his death and Clerk of the Supreme Court Elias Caldwell the organization's long-time secretary) to further that goal.[137][138] Marshall purchased a life membership two years later, in 1823 founded the Richmond and Manchester Auxiliary (becoming that branch's president), and in 1834 pledged $5000 when the organization experienced financial problems.[139]

In 1825, as Chief Justice, Marshall wrote an opinion in the case of the captured slave ship Antelope, in which he acknowledged that slavery was against natural law, but upheld the continued enslavement of approximately one-third of the ship's cargo (although the remainder were to be sent to Liberia).[140]

Recent biographer and editor of Marshall's papers Charles F. Hobson noted that multitudes of scholars dating back to Albert Beveridge and Irwin S. Rhodes understated the number of slaves Marshall owned by counting only his household slaves in Richmond,[141] and often ignored even the slaves at "Chickahominy Farm" in Henrico County, which Marshall used as a retreat.[142][143] Moreover, Marshall had received the family's thousand-acre Oak Hill plantation (farmed by enslaved labor) in Fauquier County from his father when Thomas Marshall moved to Kentucky, inherited it in 1802,[144] and in 1819 entrusted its operation to his son Thomas Marshall.

Moreover, in the mid-1790s John Marshall arranged to buy a vast estate from Lord Fairfax's heir Denny Martin, which led to years of litigation in Virginia and federal courts, some by his brother James Marshall, and Marshall even traveled to Europe to secure financing in 1796.[145] Eventually, that led to the Supreme Court's decision in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee (1816), from which Chief Justice Marshall recused himself as an interested party (but which made him wealthy).[146] In fact, Marshall arranged with his longtime friend and Associate Justice Bushrod Washington to edit and publish the late George Washington's papers in order to (re)finance that purchase.[147] Marshall's large family came to own many slaves, even if as Hobson argues Marshall derived his non-judicial income not from farming but by selling often-uncultivated western lands.[148] Research by historian Paul Finkelman revealed that Marshall may have owned hundreds of slaves, and engaged in the buying and selling of slaves throughout his life, although Hobson believes Finkelman overstated Marshall's involvement, confused purchases by relatives of the same name and noted the large gap between Marshall's documented slave purchases (in the 1780s and 1790s), and the 1830s (in which Marshall both drafted and modified his will and sold slaves to pay debts of his late son John Marshall Jr.).[149] Finkelman has repeatedly suggested that Marshall's substantial slave holdings may have influenced him to render judicial decisions in favor of slave owners.[150][151][152][153]

Personal life and family

Marshall met Mary "Polly" Ambler, the youngest daughter of state treasurer Jaquelin Ambler, during the Revolutionary War, and soon began courting her.[154] Marshall married Mary (1767–1831) on January 3, 1783, in the home of her cousin, John Ambler. They had 10 children; six of whom survived to adulthood.[125][155] Between the births of son Jaquelin Ambler in 1787 and daughter Mary in 1795, Polly Marshall suffered two miscarriages and lost two infants, which affected her health during the rest of her life.[156] The Marshalls had six children who survived until adulthood: Thomas (who would eventually serve in the Virginia House of Delegates), Jaquelin, Mary, James, and Edward.[157]

.jpg.webp)

Marshall loved his Richmond home, built in 1790,[158] and spent as much time there as possible in quiet contentment.[159][160] After his father's death in 1803, Marshall inherited the Oak Hill estate, where he and his family also spent time.[161] For approximately three months each year, Marshall lived in Washington during the Court's annual term, boarding with Justice Story during his final years at the Ringgold-Carroll House. Marshall also left Virginia for several weeks each year to serve on the circuit court in Raleigh, North Carolina. From 1810 to 1813, he also maintained the D. S. Tavern property in Albemarle County, Virginia.[162]

Marshall was not religious, and although his grandfather was a priest, never formally joined a church. He did not believe Jesus was a divine being,[163] and in some of his opinions referred to a deist "Creator of all things." He was an active Freemason and served as Grand Master of Masons in Virginia in 1794–1795 of the Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of Ancient, Free, and Accepted Masons of the Commonwealth of Virginia.[164]

While in Richmond, Marshall attended St. John's Church on Church Hill until 1814 when he led the movement to hire Robert Mills as architect of Monumental Church, which was near his home and rebuilt to commemorate 72 people who died in a theater fire. The Marshall family occupied Monumental Church's pew No. 23 and entertained the Marquis de Lafayette there during his visit to Richmond in 1824.

Other notable relatives of Marshall include first cousin U.S. Senator (Ky) Humphrey Marshall,[165] Thomas Francis Marshall,[166] Confederate Army colonel Charles Marshall, and first cousin, three times removed, General of the Army George C. Marshall.[167]

Impact and legacy

The three chief justices that had preceded Marshall: John Jay, John Rutledge, and Oliver Ellsworth, had left little permanent mark beyond setting up the forms of office. The Supreme Court, like many state supreme courts, was a minor organ of government. In his 34-year tenure, Marshall gave it the energy, weight, and dignity of what many would say is a third co-equal branch of the U.S. government. With his associate justices, especially Joseph Story, William Johnson, and Bushrod Washington, Marshall's Court brought to life the constitutional standards of the new nation.

Marshall used Federalist approaches to build a strong federal government over the opposition of the Jeffersonian Republicans, who wanted stronger state governments.[168] His influential rulings reshaped American government, making the Supreme Court the final arbiter of constitutional interpretation. The Marshall Court struck down an act of Congress in only one case (Marbury v. Madison in 1803) but that established the Court as a center of power that could overrule the Congress, the President, the states, and all lower courts if that is what a fair reading of the Constitution required. He also defended the legal rights of corporations by tying them to the individual rights of the stockholders, thereby ensuring that corporations have the same level of protection for their property as individuals had, and shielding corporations against intrusive state governments.[169]

Many commentators have written concerning Marshall's contributions to the theory and practice of judicial review. Among his strongest followers in the European tradition has been Hans Kelsen for the inclusion of the principle of judicial review in the constitutions of both Czechoslovakia and Austria. In her 2011 book on Hans Kelsen, Sandrine Baume[170] identified John Hart Ely as a significant defender of the "compatibility of judicial review with the very principles of democracy." Baume identified John Hart Ely alongside Dworkin as the foremost defenders of Marshall's principle in recent years, while the opposition to this principle of "compatibility" were identified as Bruce Ackerman[171] and Jeremy Waldron.[172] In contrast to Waldron and Ackerman, Ely and Dworkin were long-time advocates of the principle of defending the Constitution upon the lines of support they saw as strongly associated with enhanced versions of judicial review in the federal government.

Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote of Marshall and his Pulitzer Prize winning biographer Albert J. Beveridge:[173]

Senator Beveridge, in his Life of John Marshall, has shown with new vividness that the Constitution of the United States is not a document whose text was divinely inspired, and whose meaning is to be proclaimed by an anointed priesthood removed from knowledge of the stress of life. It was born of the practical needs of government; it was intended for men in their temporal relations. The deepest significant of Marshall's magistracy is his recognition of the Constitution as a living framework within which the national and the States could freely move through the inevitable growth and changes to be wrought by time and the great inventions.

The University of Virginia placed many volumes of Marshall's papers online as a searchable digital edition.[174] The Library of Congress maintains the John Marshall papers which Senator Albert Beveridge used while compiling his biography of the chief justice a century ago.[175] The Special Collections Research Center at the College of William & Mary holds other John Marshall papers in its Special Collections.[176]

Monuments and memorials

Marshall's home in Richmond, Virginia, has been preserved by Preservation Virginia (formerly known as the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities). It is considered to be an important landmark and museum, essential to an understanding of the Chief Justice's life and work.[160] Additionally, his birthplace in Fauquier County, Virginia has been preserved as the John Marshall Birthplace Park.

An engraved portrait of Marshall appears on U.S. paper money on the series 1890 and 1891 treasury notes. These rare notes are in great demand by note collectors today. Also, in 1914, an engraved portrait of Marshall was used as the central vignette on series 1914 $500 federal reserve notes. These notes are also quite scarce. (William McKinley replaced Marshall on the $500 bill in 1928.) Examples of both notes are available for viewing on the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco website.[177][178] Marshall was also featured on a commemorative silver dollar in 2005. In 1955, the United States Postal Service released the 40¢ Liberty Issue postage stamp honoring him.[179]

Chief Justice John Marshall, a bronze statue of Marshall wearing his judicial robes, stands on the ground floor inside the U.S. Supreme Court building. Unveiled in 1884, and initially placed on the west plaza of the U.S. Capitol, it was sculpted by William Wetmore Story. His father, Joseph Story, had served on the Supreme Court with Marshall.[180] Another casting of the statue is located at the north end of John Marshall Park in Washington D.C. (the sculpture The Chess Players, commemorating Marshall's love for the game of chess, is located on the east side of the park),[181] and a third is situated on the grounds of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[182]

Marshall, Michigan, was named in his honor five years before Marshall's death. It was the first of dozens of communities and counties named for him.[183] Marshall County, Kentucky,[184] Marshall County, Illinois,[185] Marshall County, Indiana,[186] Marshall County, Iowa,[187] and Marshall County, West Virginia,[185] are also named in his honor. Marshall College, named in honor of Chief Justice Marshall, officially opened in 1836. After a merger with Franklin College in 1853, the school was renamed as Franklin and Marshall College and relocated to Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[188] Marshall University,[189] Cleveland–Marshall College of Law,[190] John Marshall Law School (Atlanta),[191] and formerly, the John Marshall Law School (now the University of Illinois Chicago School of Law) are or were also named for Marshall.[190]

Marshall on the 1890 $20 Treasury Note, one of 53 people depicted on United States banknotes |

John Marshall on a Postal Issue of 1894 |

John Marshall 40c stamp, issue of 1958 |

On May 20, 2021, the former John Marshall Law School in Chicago announced its official change of name to University of Illinois Chicago School of Law, effective July 1.[192] The university board of trustees acknowledged that "newly discovered research",[193] uncovered by historian Paul Finkelman,[194] had revealed that Marshall was a slave trader and owner who practised "pro-slavery jurisprudence", which was deemed inappropriate for the school's namesake.[193]

Numerous elementary, middle/junior high, and high schools around the nation have been named for him.

The John Marshall commemorative dollar was minted in 2005.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Other notable relatives of Marshall include Senator Humphrey Marshall,[6] Thomas Francis Marshall,[7] Confederate Army colonel Charles Marshall, and General of the Army George Marshall.[8]

- ↑ Prior to the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804, each member of the Electoral College cast two votes, with no distinction made between votes for president and vice president. In the election of 1800, Jefferson and his ostensible running mate, Burr, each received 73 electoral votes, while Adams finished in third place with 65 votes.

- ↑ To Marshall's dismay, the Judiciary Act of 1802 also eliminated sixteen circuit court judgeships and reintroduced the requirement that the Supreme Court Justices ride circuit. Marshall rode circuit in Virginia and North Carolina, the busiest judicial circuit in the country at that time.[76]

- ↑ The Supreme Court would not strike down another federal law until the 1857 case of Dred Scott v. Sandford.[80]

- ↑ An earlier case, Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, had established that the Court could hear appeals from state courts in civil lawsuits.

References

- ↑ "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: United States Supreme Court. Archived from the original on April 15, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ↑ See here Archived March 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine for maps of where the Marshall land was located within Germantown. Cf. http://www.johnmarshallfoundation.org/john-marshall/historic-landmarks/birth-place-of-john-marshall/ Archived March 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Paul (2018), pp. 11–12

- ↑ Smith (1998), pp. 26–27

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 246

- ↑ "Marshall, Humphrey (1760–1841)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ "Marshall, Thomas Francis (1801–1864)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ ""Fully the Equal of the Best" George C. Marshall and the Virginia Military Institute" (PDF). Lexington, Virginia: George C. Marshall Foundation. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ Wood, Gordon S. (2011). Kennedy, David M. (ed.). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. The Oxford History of the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983246-0.

- ↑ Quoted in Baker (1974), p. 4 and Stites (1981), p. 7.

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 13–14

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 35

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 22

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 11

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 15, 18

- ↑ John Marshall at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 18–19

- ↑ Smith (1998), pp. 75–82

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 24–25

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 25–26

- ↑ Smith (1998) p. 105

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 27–29

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 30–31

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 34

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 35–38

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 43–44

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 45

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 87–94

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 96–99

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 157

- ↑ Flanders (1904), pp. 30–31, 38

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 107–108

- ↑ McCullough (2001), pp. 486–487

- ↑ McCullough (2001), p. 495

- ↑ McCullough (2001), pp. pp. 495–496, 502

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 167, 175–176

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 172–174

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 175

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 178–181

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 182–183

- 1 2 Smith (1998), pp. 258–259

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 184

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 186–187

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 192

- ↑ Smith (1998), pp. 268–286

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 193–194

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 196–198

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 208–209

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 215–218

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 220–221

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 218–221, 227–228

- ↑ Colvin, Nathan L.; Foley, Edward B. (2010). "The Twelfth Amendment: A Constitutional Ticking Time Bomb". University of Miami Law Review. 64 (2): 475–534. Archived from the original on February 15, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ↑ Stites (1981), pp. 77–80.

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 221–222

- ↑ Robarge (2000), p. xvi

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 222

- ↑ Quoted in Stites (1981), p. 80.

- ↑ Smith, (1998), p. 16

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 225–226

- ↑ Unger, Harlow Giles (November 16, 2014). "Why Naming John Marshall Chief Justice Was John Adams's "Greatest Gift" to the Nation". History News Network. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 232

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 223

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 3–4

- ↑ Schwartz (1993), pp. 67–68

- ↑ FindLaw Supreme Court Center: John Marshall Archived November 21, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ White (1991), pp. 157–200

- ↑ Smith (1998), pp. 351–352, 422, 506

- ↑ Albert Jeremiah Beveridge (1919), The life of John Marshall, vol. 4, p. 94

- ↑ Hobson (1996), pp. 15–16, 119–123

- ↑ George Gibbs (1846), Memoirs of the Administrations of Washington and John Adams, vol. II, p. 350.

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 298–299, 306–308

- ↑ Fox, John. "Expanding Democracy, Biographies of the Robes: John Marshall". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 1, 2017..

- 1 2 Currie (1992), pp. 152–155

- ↑ A reliable statement of the quote was recounted by Theophilus Parsons, a law professor who knew Marshall personally. Parsons (August 20, 1870), "Distinguished Lawyers," Albany Law Journal, pp. 126–127 online Archived December 16, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Historian Edward Corwin garbled the quote to: "Now Story, that is the law; you find the precedents for it," and that incorrect version has been repeated. Edward Corwin (1919), John Marshall and the Constitution: a chronicle of the Supreme Court. p. 119.

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 243–247

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 246–247, 250

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 251–252

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 252–253

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 255–257

- 1 2 Paul (2018), p. 257

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 258–259

- ↑ Gordon S. Wood; ed. by Robert A. Licht (1993), "Judicial Review in the Era of the Founding" in Is the Supreme Court the guardian of the Constitution?, pp. 153–166

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 260–261

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 276–277

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 279–280

- 1 2 "Senate Prepares for Impeachment Trial". United States Senate. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Linda (April 10, 1996). "Rehnquist Joins Fray on Rulings, Defending Judicial Independence". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 31, 2009.

the 1805 Senate trial of Justice Samuel Chase, who had been impeached by the House of Representatives … This decision by the Senate was enormously important in securing the kind of judicial independence contemplated by Article III" of the Constitution, Chief Justice Rehnquist said

- ↑ Hobson (2006), pp. 1430–1431, 1434–1435

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 282–283

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 291–292

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 293–295

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 300–303

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 304–305

- ↑ Currie (1992), p. 136

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 339–341

- ↑ Paul (2018), p. 341

- ↑ Edward Samuel Corwin (1919), John Marshall and the Constitution: a chronicle of the Supreme Court, p. 133

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 341–342

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 342–344

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 344–345

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 345–346

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 365–367

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 368–370

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 370–371

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 386–387

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 410–412

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 388–389, 396–397

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 399–405

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 412–413

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 414–416

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 419–420

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 421–423

- ↑ Boller, Paul F.; John H. George (1989). They Never Said It: A Book of False Quotes, Misquotes, & False Attributions. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-506469-8. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 423–425

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 267–270

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 335–338

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 375–380

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 382–383

- ↑ Hobson (2006), p. 1437

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 247–250

- ↑ Foran, William A (October 1937). "John Marshall as a Historian". American Historical Review. 43 (1): 51–64. doi:10.2307/1840187. JSTOR 1840187..

- ↑ "Note". Online Library of Liberty. Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2010..

- ↑ Marshall, John. "Abridgment". Cary & Lea. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ↑ "1830 Virginia Constitution". www.wvculture.org. Archived from the original on September 26, 2006. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Determining the Facts, Reading 3: A Locket and a Strand of Hair—Symbols of Love and Family". Teaching with Historic Places: "The Great Chief Justice" at Home. Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on May 15, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ↑ Smith. John Marshall. p. 523.

- ↑ "John Marshall Biography: Supreme Court Justice (1755–1835)". www.biography.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ Thayer, James Bradley, "John Marshall," The Atlantic Monthly, March 1901 (retrieved Dec. 18, 2022).

- ↑ Christensen, George A. "Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices". Yearbook 1983 Supreme Court Historical Society. Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court Historical Society (1983): 17–30. Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved June 5, 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Fox-Genovese, Elizabeth; Genovese, Eugene D. (2005). The Mind of the Master Class: History and Faith in the Southern Slaveholders' Worldview. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 9780521850650. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ↑ "Nominations". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Secretary, United States Senate. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ Finkelman, Paul (August 31, 2020). "Master John Marshall and the Problem of Slavery". lawreviewblog.uchicago.edu. The University of Chicago Law Review Online. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ↑ Frances Howell Rudko, "Pause at the Rubicon, John Marshall and Emancipation: Reparations in the early national period", 35 John Marshall Law Review 75, 77-78 (2001)

- ↑ Last Will and Testament, partial transcribed manuscript at Library of Virginia, original having been lost during the Richmond fire set during the Confederate retreat, but portions having been transcribed during an Alexandria Virginia court case.

- ↑ Rudko, p. 81 et seq.

- 1 2 Rudko at p. 78

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 46–48

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 49–51

- ↑ Rudko p. 84

- ↑ Bryant, Jonathan M., Dark Places of the Earth: The Voyage of the Slave Ship Antelope (Liveright, 2015) pp. 227–239. ISBN 978-0871406750

- ↑ Charles F. Hobson, Review Essay: Paul Finkelman's Supreme Injustice, 43 J. S.Ct. History pp. 363, 365-367(2018)

- ↑ Henrico County erected a historical marker in 2005 https://ww.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=20730%5B%5D

- ↑ The Marshall dwelling having been destroyed before the American Civil War, trenches were dug on the property in 1862. The current historic house/event center was built in 1918 and it and surrounding gardens are now a park. https://henrico.us/rec/places/armour-house/ Archived July 20, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Moving his household there according to Paul (2018) p.

- ↑ Paul (2018) p.

- ↑ "The Founders and the Pursuit of Land". Archived from the original on August 12, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ↑ Lawrence B. Custer, "Bushrod Washington and John Marshall: a preliminary inquiry" 4 Am.J. Legal Hist. 34, 43 (1960)

- ↑ Hobson pp. 368-369

- ↑ Hobson p. 66

- ↑ Finkelman (2016)

- ↑ Finkelman (2018)

- ↑ Much of Chapter 2 of his 2018 Supreme Injustice book was reprinted (without addressing Rudko's cited work nor Hobson's published concerns but thanking Hobson and others for reviewing a draft) in the 2020 U.Chi.L.Rev. Online on August 31, 2020, as "Master John Marshall and the Problem of Slavery Archived August 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine" and "John Marshall's Proslavery Jurisprudence: Racism, Property, and the "Great" Chief Justice Archived August 21, 2021, at the Wayback Machine"

- ↑ "America's 'Great Chief Justice' Was an Unrepentant Slaveholder". www.msn.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 21–22

- ↑ Albert Beveridge, Life of John Marshall pp. 72–73

- ↑ Newmyer (2001), p. 34

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 299–300

- ↑ "John Marshall House, Richmond, Virginia". Archived from the original on October 13, 2005.

- ↑ "National Park Service, Marshall's Richmond home".

- 1 2 National Park Service, "The Great Chief Justice" at Home, Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) lesson plan

- ↑ Paul (2018), pp. 275–276

- ↑ Clarence J. Elder & Margaret Pearson Welsh (August 1983). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: D. S. Tavern" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- ↑ Smith. John Marshall. pp. 36, 406..

- ↑ Tignor, Thomas A. The Greatest and Best: Brother John Marshall at Archived January 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine masonicworld.com.

- ↑ "Marshall, Humphrey (1760–1841)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ "Marshall, Thomas Francis (1801–1864)". Biographical Dictionary of the United States Congress 1774 – Present. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ ""Fully the Equal of the Best" George C. Marshall and the Virginia Military Institute" (PDF). Lexington, Virginia: George C. Marshall Foundation. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ↑ Smith (1998), p. 8

- ↑ Newmyer (2007), p. 251

- ↑ Baume, Sandrine (2011). Hans Kelsen and the Case for Democracy, ECPR Press, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Ackerman, Bruce (1991). We the People.

- ↑ Waldron, Jeremy (2006). "The Core of the case against judicial review," The Yale Law Review, 2006, Vol. 115, pp. 1346–406.

- ↑ Kurland, Philip, ed. (1970). Felix Frankfurter on the Supreme Court: Extrajudicial Essays on the Court and the Constitution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- ↑ "The Papers of John Marshall Digital Edition". rotunda.upress.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ↑ Beveridge, Albert J. (Albert Jeremiah). "Albert Jeremiah Beveridge collection of John Marshall papers, 1776–1844". Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ "John Marshall Papers". Special Collections Research Center, Earl Gregg Swem Library, College of William & Mary. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Pictures of large size Federal Reserve Notes featuring John Marshall, provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco". Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved August 3, 2006.

- ↑ Pictures of US Treasury Notes featuring John Marshall, provided by the Archived January 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

- ↑ Rod, Steven J. (May 16, 2006). "Arago: 40-cent Marshall". National Postal Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ↑ "Statue of John Marshall". Architects Virtual Capitol. Architect of the Capitol, Washington, DC. Archived from the original on June 5, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ↑ Goode, James M; Seferlis, Clift A (2008). Washington sculpture : a cultural history of outdoor sculpture in the nation's capital. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801888106. OCLC 183610465.

- ↑ Waite, Morrison Remick; Rawle, William Henry; Association, Philadelphia Bar (1884). Exercises at the ceremony of unveiling the statue of John by Morrison Remick Waite, William Henry Rawle, Philadelphia Bar Association. pp. 1, 3, 5, 9, 23–29. Archived from the original on August 15, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ↑ City of Marshall, Michigan

- ↑ The Register of the Kentucky State Historical Society, Volume 1. Kentucky State Historical Society. 1903. p. 36.

- 1 2 Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 200.

- ↑ De Witt Clinton Goodrich & Charles Richard Tuttle (1875). An Illustrated History of the State of Indiana. Indiana: R. S. Peale & co. pp. 567.

- ↑ "Courthouse History – Marshall County, Iowa". Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ↑ "Mission and History". Franklin & Marshall University. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ↑ Brown, Lisle, ed."Marshall Academy, 1837." Archived June 28, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Marshall University Special Collections. September 1, 2004, Dec 20. 2006.

- 1 2 Newmyer, R. Kent (2001). John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court. LSU Press. p. 477. ISBN 978-0807127018. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ↑ "Atlanta's John Marshall Law School". The Law School Admission Council. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- ↑ "UIC Removes John Marshall's Name From Law School Due to Slave Ownership". NBC Chicago. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2021.

- 1 2 "UIC renaming John Marshall Law School" Archived May 24, 2021, at the Wayback Machine by Stefano Esposito, Chicago Sun-Times, May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ↑ "Editorial: A law school discounts John Marshall’s positive legacy" Archived July 5, 2021, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Tribune, May 25, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

Works cited

- Currie, David (1992). The Constitution in the Supreme Court: The First Hundred Years, 1789–1888. University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-13109-2.

- Finkelman, Paul (2016). CollegeOfLawUsask (November 21, 2016). "Ariel Sallows Lecture presented by Paul Finkelman". Archived from the original on November 3, 2021 – via YouTube.

- Finkelman, Paul (2018). Supreme Injustice: Slavery in the Nation's Highest Court. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard U.P. ISBN 9780674051218.

- Flanders, Henry (1904). The Life of John Marshall. T. & J.W. Johnson & Company.

- Hobson, Charles F. (2006). "Defining the Office: John Marshall as Chief Justice". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 154 (6): 1421–1461. doi:10.2307/40041344. JSTOR 40041344.

- Hobson, Charles F. (1996). The Great Chief Justice: John Marshall and the Rule of Law. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0700607884.

- McCullough, David (2001). John Adams. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4165-7588-7.

- Newmyer, R. Kent (2001). John Marshall and the Heroic Age of the Supreme Court. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2701-8.

- Paul, Joel Richard (2018). Without Precedent: Chief Justice John Marshall and His Times. Riverhead Books. ISBN 978-1594488238.

- Schwartz, Bernard (1993). A History of the Supreme Court. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195080995.

- Smith, Jean Edward (1998) [1996]. John Marshall: Definer Of A Nation (Reprint ed.). Owl Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-5510-8.

- Stites, Francis N. (1981). John Marshall Defender of the Constitution. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-673-39353-1.

- White, G. Edward (1991). The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815–1835 (Abridged ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195070583.

Further reading

Secondary sources

- Abraham, Henry Julian (2008). Justices, Presidents, and Senators: A History of the U.S. Supreme Court Appointments from Washington to Bush II. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742558953.

- Baker, Leonard (1974). John Marshall: A Life in the Law. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0025063600.

- Beveridge, Albert J. The Life of John Marshall, in 4 volumes (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1919), winner of the Pulitzer Prize, Volume I, Volume II Archived January 31, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Volume III and Volume IV at Internet Archive.

- Brookhiser, Richard (2018). John Marshall: The Man Who Made the Supreme Court. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465096237.

- Clinton, Robert Lowry (2008). The Marshall Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576078433.

- Corwin, Edwin S. (2009) [1919]. John Marshall and the Constitution: A Chronicle of the Supreme Court. Dodo Press. ISBN 978-1409965558. online Edition Archived July 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine at Project Gutenberg

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers.

- Goldstone, Lawrence (2008). The Activist: John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, and the Myth of Judicial Review. Walker. ISBN 978-0802714886.