The dome of the Cappella dei Principi dominates the San Lorenzo architectural complex | |

| Location | Florence, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 43°46′30″N 11°15′12″E / 43.7751°N 11.2534°E |

| Type | Art, Architecture |

| Visitors | 321,043 |

| Director | Monica Bietti |

The Medici Chapels (Cappelle medicee) are two structures at the Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence, Italy, dating from the 16th and 17th centuries, and built as extensions to Brunelleschi's 15th-century church, with the purpose of celebrating the Medici family, patrons of the church and Grand Dukes of Tuscany. The Sagrestia Nuova ("New Sacristy") was designed by Michelangelo. The larger Cappella dei Principi ("Chapel of the Princes"), although proposed in the 16th century, was not begun until the early 17th century, its design being a collaboration between the family and architects.

These are not to be confused with the Magi Chapel in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi, then the main Medici home, that houses a famous cycle of frescoes by Benozzo Gozzoli, painted around 1459.

The Sagrestia Nuova

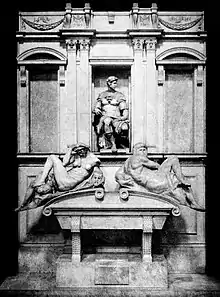

The Sagrestia Nuova[1] was intended by Cardinal Giulio de' Medici and his cousin Pope Leo X as a mausoleum or mortuary chapel for members of the Medici family. It balances Brunelleschi's Sagrestia Vecchia, the "Old Sacristy" nestled between the left transept of San Lorenzo, with which it consciously competes, and shares its format of a cubical space surmounted by a dome, of gray pietra serena and whitewashed walls. It was the first essay in architecture (1519–24) of Michelangelo,[2] who also designed its monuments that are dedicated to certain members of the Medici family, with sculptural figures of the four times of day[3] that were destined to influence sculptural figures reclining on architraves for many generations to come. The Sagrestia Nuova was entered by a discreet entrance in a corner of San Lorenzo's right transept, now closed.[4]

Although it was vaulted over by 1524, the ambitious projects of its sculpture and the intervention of events, such as the temporary exile of the Medici (1527), the death of Giulio, eventually Pope Clement VII, and the permanent departure of Michelangelo for Rome in 1534, meant that Michelangelo never finished it.

In 1976, a concealed corridor with drawings by Michelangelo on its walls was discovered under the New Sacristy.[5][6]

The Madonna and Child was the first sculpture Michelangelo completed for the project and although most of the following statues had been carved by the time of Michelangelo's departure, they had not been put in place, being left in disarray across the chapel. Later, in 1545, they were installed by Niccolò Tribolo.[7] By order of Cosimo I, Giorgio Vasari and Bartolomeo Ammannati finished the work by 1555.[8]

Four Medici tombs were intended for the project, but those of Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano (buried beneath the altar at the entrance wall) were never begun. The magnificent existing tombs are those of two more recently deceased and less well known family members whose careers had been cut tragically short by their comparatively early deaths: Giuliano di Lorenzo, Duke of Nemours (d. 1514, aged 37) and his nephew (d. 1519, age 27) Lorenzo di Piero, Duke of Urbino, whose daughter Catherine de' Medici became Queen of France). The architectural components of these tombs are similar and with sculptures offering contrast.

Madonna and Child and patron saints

On the main wall, Michelangelo's Madonna and Child is flanked by the Medici patron saints, Cosmas and Damian.[9] The wall is unfinished. These three sculptures are placed over a rectangular altar. The sculptures of the saints were not carved by Michelangelo. Following models created by Michelangelo, the sculptures of the patron saints were executed later by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli and Raffaello da Montelupo respectively and were placed on either side of the Madonna and Child.

The statues representing the Medici family members above their respective tombs along the side walls are facing the Madonna and their lines of sight lead to her.

Side tombs

In a statement in the biography of Michelangelo that was published in 1553 by his disciple, Ascanio Condivi, and largely was based on Michelangelo's own recollections, Condivi gives the following description of the sculptures on the two Medici tombs: "The statues are four in number, placed in a sacristy... the sarcophagi are placed before the side walls, and on the lids of each there recline two big figures, larger than life, to wit, a man and a woman; they signify Day and Night and, in conjunction, Time which devours all things… And in order to signify Time he planned to make a mouse, having left a bit of marble upon the work (which [plan] he subsequently did not carry out because he was prevented by circumstances), because this little animal ceaselessly gnaws and consumes just as time devours everything”.[10] [11]

Day

_by_shakko_04.jpg.webp)

Day is a marble sculpture by Michelangelo, datable to 1526–1531. It is paired with Night on the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici in the chapel.

Night

Night is a sculpture in marble (155x150 cm, maximum length 194 cm diagonally) by Michelangelo Buonarroti. Dating from 1526–1531, it is part of the decoration of the New Sacristy and part of an allegory of the four parts of a day. It is situated on the left of the sarcophagus of the tomb of Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Nemours.

Along with his Dawn, Michelangelo drew from the ancient Sleeping Ariadne for his sculpture's pose.[12]

Associated poetry about Night

In his poem "L'Idéal" from Les Fleurs du Mal, French Romantic poet Charles Baudelaire references the statue:

- Ou bien toi, grande Nuit, fille de Michel-Ange,

- Qui tors paisiblement dans une pose étrange

- Tes appas façonnés aux bouches des Titans!

- Or you, great Night, daughter of Michelangelo,

- Who calmly contort, reclining in a strange pose

- Your charms molded by the mouths of Titans![13]

In his Life of Michelangelo, Giorgio Vasari quotes an epigram by Giovanni Strozzi, written, perhaps in 1544, in praise of Michelangelo's Night:

- Night, whom you see sleeping in such sweet attitudes

- was carved in this stone by an Angel

- and although she sleeps, she has life:

- wake her, if you don't believe it, and she will speak to you.[16]

_by_shakko_03.jpg.webp)

Michelangelo responded in 1545–46 with another epigram, entitled "Risposta del Buonarroto" (Buonarroto's response). Speaking in the voice of the statue, it may contain a scathing critique of Cosimo I de' Medici's governance, according to Kenneth Gross:[17]

- Caro m'è 'l sonno, e più l'esser di sasso,

- mentre che 'l danno e la vergogna dura;

- non veder, non sentir m'è gran ventura;

- però non mi destar, deh, parla basso.[15]

- My sleep is dear to me, and more dear this being of stone,

- as long as the agony and shame last.

- Not to see, not to hear [or feel] is for me the best fortune.;

- So do not wake me! Speak softly.[18]

Dawn

Dawn is a sculpture by Michelangelo, executed for the chapel. It is 6 feet and 8 inches in length. Along with his Night, Michelangelo drew from the ancient Sleeping Ariadne for his sculpture's pose.[19] This was in turn influential on Benvenuto Cellini's Diana of Fontainebleau.[20]

Dusk

_by_shakko_05.jpg.webp)

Dusk is a marble sculpture by Michelangelo, datable to 1524–1534. It is paired with Dawn on the tomb of Lorenzo II de' Medici.

The creation of Dusk started simultaneously with the resuming of work at the New Sacristy of Florence, during 1524, after Clement VII's election to the papal throne. The sculpture's termination date remains unknown; however, the works were interrupted during the Siege of Florence and resumed in 1531. The work remained visibly unfinished in 1534, the year that Michelangelo definitively left Florence.

Dusk, or Sunset, is personified as man and is stretched out and nude, as are the other statues in the series. It was modelled, perhaps, after the mountain and river gods at the Arch of Septimius Severus in Rome.

If its pair, Dawn is in the act of awaking, Dusk is falling asleep. The statue lies down with one leg crossing the other, for greater compositional dynamism, one arm resting on his thigh to hold back a falling cloth. The other arm is bent to support the figure. The statue's face is bearded, with a thoughtful, downward gaze.

Among the various iconographic meanings proposed, the statue is seen as an emblem of the phlegmatic temperament or of the elements of water or earth. Michelangelo's study for Dusk is known for exemplifying his style of striking, unfinished drawings.[21]

Gallery of Dusk images

Dusk

Dusk Study of Dusk by Tintoretto

Study of Dusk by Tintoretto Detail of Dusk's feet

Detail of Dusk's feet

The lantern

The lantern at the top of the New Sacristy is made out of marble and has an "...unusual polyhedron mounted on the peak of the conical roof".[22] The orb that is on top of the lantern has seventy-two facets and is approximately two feet in diameter. The orb and cross, that is on top of the orb, are traditional symbols of the Roman and Christian power, and recalls the similar orbs on central dome plan churches such as St. Maria del Fiore and St. Peter's. But because it is on a private mausoleum, the Medici family is promoting their own personal power with the orb and cross, laurel wreath, and lion heads, which are all symbols of status and power.

The lantern that holds up the orb helps to accentuate the height and size of the chapel, which is fairly small. The lantern is a bit less than seven meters tall and "...is equal to the height of the dome it surmounts".[22] The lantern metaphorically expresses the themes of death and resurrection. The lantern is where the soul could escape and go from "...death to the afterlife".[22]

Cappella dei Principi

_-_n._3515_-_Firenze_-_S._Lorenzo_Cappella_dei_Principi_(1870s).jpg.webp)

The octagonal Cappella dei Principi surmounted by a tall dome, 59 m. high, is the distinguishing feature of San Lorenzo when seen from a distance. It is on the same axis as the nave and chancel to which it provides the equivalent of an apsidal chapel. Its entrance is from the exterior,[23] in Piazza Madonna degli Aldobrandini, and through the low vaulted crypt planned by Bernardo Buontalenti before plans for the chapel above were made.[24]

The opulent Cappella dei Principi, an idea formulated by Cosimo I, was put into effect by Ferdinand I de' Medici. It was designed by Matteo Nigetti, following some sketches tendered to an informal competition of 1602 by Don Giovanni de' Medici, the natural son of Cosimo I, Grand Duke of Tuscany, which were altered in the execution by the aged Buontalenti.[25] A true expression of court art, it was the result of collaboration among designers and patrons.

For the execution of its astonishing revetment of marbles inlaid with colored marbles and semi-precious stone, the Grand Ducal hardstone workshop, the Opificio delle Pietre Dure was established. The art of commessi, as it was called in Florence, assembled jig-sawn fragments of specimen stones and porphyry to form the designs of the revetment that entirely cover the walls. The result was disapproved of by 18th- and 19th-century visitors, but has come to be appreciated for an example of the taste of its time.[26] Six grand sarcophagi are empty; the Medici remains are interred in the crypt below. In sixteen compartments of the dado are coats-of-arms of Tuscan cities under Medici control. In the niches that were intended to hold portrait sculptures of Medici, two were executed by Pietro Tacca (1626–42) that feature Ferdinando I and Cosimo II.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Charles de Tolnay, Michelangelo, vol. III "The Medici Chapel" (Princeton, 1948); James S. Ackerman, The Architecture of Michelangelo

- ↑ William E. Wallas, Michelangelo at San Lorenzo. The Genius as Entrepreneur, Cambridge University Press, 1995, p.

- ↑ Michelangelo left no note of his "allegories" as he called them; the identification as Night and Day, Dawn and Dusk was first offered by Benedetto Varchi, 1549

- ↑ Modern entrance, which requires a ticket, is through the Cappella dei Principi.

- ↑ Peter Barenboim, Sergey Shiyan, Michelangelo: Mysteries of Medici Chapel, SLOVO, Moscow, 2006. ISBN 5-85050-825-2

- ↑ Peter Barenboim, "Michelangelo Drawings – Key to the Medici Chapel Interpretation", Moscow, Letny Sad, 2006, ISBN 5-98856-016-4

- ↑ Avery, Charles (1970). Florentine Renaissance Sculpture. John Murray Publishing. p. 190.

- ↑ Antonio Paolucci. The Museum of the Medici Chapels and the Church of San Lorenzo. Sillabe Publishing 1999.

- ↑ The doctor-saints (medici) hold their doctor's boxes of salves and nostrums.

- ↑ Panofsky, Erwin. (1964). "The Mouse That Michelangelo Failed to Carve" (PDF) (Essays In Memory of Karl Lehmann ed.). N.Y.: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University: 242–255.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Barenboim P. D. / Peter Barenboim. (2017). "The Mouse that Michelangelo Did Carve in the Medici Chapel: An Oriental Comment to the Famous Article of Erwin Panofsky".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Regoli, Gigetta Dalli; Gioseffi, Decio; Mellini, Gian Lorenzo; Salvini, Roberto (1968). Vatican Museums: Rome. Italy: Newsweek. p. 27.

- ↑ Baudelaire, Charles. Trans. William Aggeler. "L'Idéal." http://fleursdumal.org/poem/117

- ↑ Vasari, Giorgio, 1511-1574 (2017). "Vita di Michelagnolo Buonarroti". Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori. ISBN 978-88-6274-759-2. OCLC 993450831.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 Michelangelo Buonarroti, Ettore Barelli (a cura di), Rime, Milano, 2001, p. 261.

- ↑ Kenneth Gross, Dream of the Moving Statue, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006 , p. 92.

- ↑ Kenneth Gross, ibidem, p. 96.

- ↑ Kenneth Gross, ibidem, p. 94.

- ↑ Regoli, Gigetta Dalli; Gioseffi, Decio; Mellini, Gian Lorenzo; Salvini, Roberto (1968). Vatican Museums: Rome. Italy: Newsweek. p. 27.

- ↑ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 672. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- ↑ Nechvatal, Joseph (6 February 2018). "Michelangelo Traces the States of Being and Non-being". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- 1 2 3 Wallace, William (1989). "The Lantern of Michelangelo's Medici Chapel". Mitteilungen des Kunsthistorischen Institutes in Florenz.

- ↑ A sequence of small spaces leads from the Sagrestia Nuova also.

- ↑ In the separate, earlier crypt beneath the nave of the basilica are buried Cosimo de' Medici and Donatello.

- ↑ Touring Club Italiano, Firenze e dintorni (Milan, 1964) p. 285f.

- ↑ TCI, Firenze e dintorni 1964:286: "indeed, conceived according to the Baroque aim of arousing stupefaction" (concepita già secondo il fine barocco di destare stupore).

References

- Edith Balas, "Michelangelo's Medici Chapel: A New Interpretation", Philadelphia, 1995

- Barenboim, Peter (with Heath, Arthur). 500 years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel, LOOM, Moscow, 2019. ISBN 978-5-906072-42-9

- Peter Barenboim, "Michelangelo Drawings: Key to the Medici Chapel Interpretation", Moscow, Letny Sad, 2006, ISBN 5-98856-016-4

- Peter Barenboim, Alexander Zakharov, "Mouse of Medici and Michelangelo: Medici Chapel / Il topo dei Medici e Michelangelo: Cappelle Medicee", Mosca, Letni Sad, 2006. ISBN 5-98856-012-1

- Peter Barenboim, Sergey Shiyan, Michelangelo: Mysteries of the Medici Chapel, SLOVO, Moscow, 2006. ISBN 5-85050-825-2

- Peter Barenboim, Sergey Shiyan, Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel: Genius in details (English, Russian). Moscow, Looom, 2011, ISBN 978-5-9903067-1-4

- James Beck, Antonio Paolucci, Bruno Santi, "Michelangelo. The Medici Chapel", Thames and Hudson, New York, 1994, ISBN 0-500-23690-9

- Panofsky, Erwin. (1964). "The Mouse That Michelangelo Failed to Carve" (PDF) (Essays In Memory of Karl Lehmann ed.). N.Y.: Institute of Fine Arts, New York University: 242–255.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Barenboim P. D. / Peter Barenboim. (2017). "The Mouse that Michelangelo Did Carve in the Medici Chapel: An Oriental Comment to the Famous Article of Erwin Panofsky".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - William E. Wallace,"Michelangelo at San Lorenzo: Genius as Entrepreneur", Cambridge University Press, 1995, ISBN 0-521-41021-5

Bibliography

- Baldini, Umberto (1973). Michelangelo scultore (in Italian). Rizzoli.

- González, Marta Alvarez (2008). Michelangelo (in Italian) (Nuova ed.). Milano: Mondadori arte. ISBN 978-88-370-6434-1.

External links

![]() Media related to Medici Chapel (Basilica of San Lorenzo) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Medici Chapel (Basilica of San Lorenzo) at Wikimedia Commons