| New Sacristy | |

|---|---|

Sagrestia Nuova | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | |

| Location | Piazza Madonna degli Aldobrandini, Florence, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 43°46′30″N 11°15′13″E / 43.77500°N 11.25361°E |

| Architecture | |

| Date established | 1520 |

| Completed | 1533 |

The Sagrestia Nuova, also known as the New Sacristy in English, is a mausoleum that stands as a testament to the grandeur and artistic vision of the Medici family. Constructed in 1520, the mausoleum was designed by the Italian artist Michelangelo. Situated adjacent to the Basilica di San Lorenzo in Florence, Italy, the Sagrestia Nuova forms an integral part of the museum complex known as the Medici Chapels.[1]

History

The Medici family, one of the most influential and powerful families during the Italian Renaissance, played a pivotal role in the political, economic, and cultural landscape of Florence. With their immense wealth and patronage of the arts, the Medici became patrons to many great artists, including Michelangelo.

Commissioned by Pope Clement VII, a member of the Medici family, Michelangelo embarked on the ambitious project of designing and constructing a mausoleum that would serve as the final resting place for members of the Medici dynasty. The Sagrestia Nuova was specifically intended to house the remains of two notable Medici figures: Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours, and Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino.

The Sagrestia Nuova is a testament to Michelangelo's genius and artistic prowess. The mausoleum showcases his mastery in both architecture and sculpture. Michelangelo carefully designed the space, taking into consideration the harmony between the structure and the sculptures that would adorn it. The mausoleum's architecture reflects Michelangelo's skillful understanding of balance, proportion, and the manipulation of light.

As visitors enter the Medici Chapel, they are greeted by a sense of grandeur and solemnity. The space is divided into two rooms: the Cappella dei Principi (Chapel of the Princes) and the Sagrestia Nuova. The Cappella dei Principi, the larger of the two rooms, features a stunning dome adorned with intricate frescoes and an imposing coffered ceiling. The walls are adorned with elegant marble panels, creating an ambiance of opulence and magnificence.

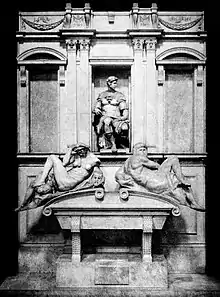

The Sagrestia Nuova is a smaller, more intimate space. Its main focal points are the grand Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours, and the Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici Duke of Urbino, which are sculpted with exquisite attention to detail. Michelangelo's sculptures beautifully capture the essence of the Medici family, depicting them in a solemn and dignified manner. These sculptures, known as the Medici Tombs, are considered some of Michelangelo's finest works and a testament to his ability to bring marble to life.

The Sagrestia Nuova serves as a significant historical and cultural landmark, offering visitors a glimpse into the rich legacy of the Medici family. Beyond its architectural and artistic value, it also serves as a reminder of the Medici's contributions to the arts and their enduring influence on Florentine society.

Today, the Sagrestia Nuova is open to the public as part of the Medici Chapels museum complex. Visitors can appreciate Michelangelo's genius up close, marvel at the intricate details of the sculptures, and immerse themselves in the historical and artistic significance of the Medici family.

Premises

The death of the two descendants of the Medici family, Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours, in 1516 and Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, in 1519, had deeply embittered Pope Leo X, respectively brother and uncle of the two, who wanted to ensure that they obtained a princely burial. It was also suggested by their cousin Giulio de' Medici, cardinal and later Pope Clement VII in 1523, commissioning Michelangelo's project for the façade for Basilica di San Lorenzo, engaging the artist in a new project for the basilica. The church had been the burial place of the Medici family for a century, but at the time there were no spaces available in which to create a new monumental complex: the historic family chapel, the Old Sacristy, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi and Donatello, was a set of sober and measured balance, in which no other decorations could be added without compromising the whole. The crypt, where some family members are located, was not up to the clients' wishes for splendor and celebration. Not even for Lorenzo de' Medici and his brother Giuliano de' Medici had a worthy burial been prepared. There was a need to create a new environment to place the remains of the two "dukes" (or "captains") and the two "magnificents".[2]

Design

Michelangelo was chosen for the construction, recovering from the impasse on the façade project, whose contract was definitively terminated in March 1520. The exact contracting document is not known, but from other documents and letters it is clear, that in March work on a new chapel had been started.[2]

An independent room was designed, symmetrical and similar in proportion to Brunelleschi's sacristy, at the crossroads between the transept and the chevet on the north side. The plan chosen was completely like the model: a square base with a scarsella on the west side in a ratio of 1/3, and two service rooms on either side of the scarsella, all covered by a dome with lantern.

During the design phase, Michelangelo thought of various solutions, before choosing the version implemented. The question was how to arrange the four sepulchers in relation to the available space, with the altar and the entrance. The first idea was tombs placed at the corners leaning against the walls (March 1520), but on 23 October 1520, Michelangelo presented Cardinal Giulio with a project with an aedicula in the center containing the tombs. A drawing was provided on 21 December 1520.[2] The artist therefore abandoned the scheme of the tombs in the center, opting for their arrangement against the walls and studying variants with single or double burials, until arriving at a defined project with single tombs for the dukes in the side walls and double ones for the magnificents on the wall opposite the altar. Only those of the dukes were finally completed.[2] In 1521 Pope Leo died and work was interrupted.[2]

Second stage

With the election of Clement VII in 1523, in December of that year the artist returned to the works at San Lorenzo. It was thought to house the tombs of Pope Leo and, at the time, of Clement VII in the Sacristy, but the idea was soon abandoned in favor of the choir of San Lorenzo. In the end, however, both were buried in Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.[2]

In the spring of 1524, Michelangelo was working on the clay models for the sculptures and in the autumn the marbles arrived from Carrara. Between 1525 and 1527 at least four statues were completed (including the Night and the Dawn) and four others were already defined with the models.[2]

In 1526, the first tomb was walled up, the Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino. On 17 June, the artist sent a letter to Rome in which he wrote: "I work as hard as I can, and in fifteen days I'll get the other captain started, then I'll be left, of matters of importance, only and four figures. The four figures on the cassoni, the four figures on the ground, which are Rivers, and two captains and Our Lady going to the tomb at the head, are the figures I would like to make with my own hand: and of these there are six begun, and the courage is enough for me to do them in the right time and partly do the others that don't matter so much". It is therefore understood that in addition to the extant sculptures, four river allegories were also envisaged (the rivers of Hades, or perhaps the rivers under Medici rule) lying at the foot of the tombs; the only surviving work that relates to these is the model of the River God at Casa Buonarroti.[2]

Interrupting and resuming jobs

With the heavy blow received by Pope Clement during the Sack of Rome in 1527, the city of Florence rebelled against the Medici rule, driving out the little loved duke Alessandro de' Medici. Michelangelo, despite being linked to the Medici by working relationships since his youth, blatantly sided with the republican faction, actively participating, as person in charge of the fortifications, in the defense measures against the siege of the city in 1529–1530. When the Florentines were defeated Michelangelo fled the city, but was declared a rebel and presented himself voluntarily to avoid more serious punitive measures. Clement VII's pardon was not long in coming, provided that the artist immediately resume work in San Lorenzo where, in addition to the Sacristy, the project for a monumental Laurentian Library had been added five years earlier. It is clear how the pope was moved by the awareness of his not being able to renounce the only artist capable of giving shape to the dreams of glory of his dynasty, despite his ingratitude towards and betrayal of the Medici.[3]

In April 1531, work resumed on the Sacristy and by the summer two more statues had to be completed and a third started. It is also known that the Portrait of Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, was executed between 1531 and 1534, while the Portrait of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours, was given to Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli in 1533 for finishing. In that same period the artist was preparing two allegorical statues, the Heaven and the Earth, which were to have been sculpted by Niccolò Tribolo and placed in the niches on the sides of Giuliano's tomb; these however remained empty. Two more evidently had to be planned for the tomb of Lorenzo.[2]

In the meantime, between 1532 and 1533, on a project by Michelangelo who had already sent sketches from Rome in 1526, the painter and architect Giovanni da Udine worked on stuccoes and decorations in the dome, of which no trace remains after the eighteenth-century interventions promoted by the Electress Palatine Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici who covered the dome with only stucco as it appears to us today.

The Florentine works by now proceeded ever more slowly because in those same years Michelangelo was also working, in addition to the library, on the tomb of Julius II, for which he was preparing the Slaves. Michelangelo, not happy with the city's political climate, took the opportunity to take new assignments in Rome and left Florence, in 1534, never setting foot there again.[3]

In 1559, on the initiative of Cosimo I de' Medici, the chapel was arranged according to the project by Giorgio Vasari. Although an entire wall with the tomb of the "Magnificent" was missing and the river deities, statues, stuccoes and frescoes required by the contract had yet to be created, the Sacristy was considered completed.[2]

Architecture

.%22_-_51196081754_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Born in the midst of such tumultuous events, the New Sacristy is a very innovative work. Starting from the same plan of the Old Sacristy, Michelangelo divided the space into more complex forms, treating the walls with floors at different levels in complete freedom. On these he cut out classical elements such as arches, pillars, balustrades and frames, now in marble and now in pietra serena, however arranged in completely new shapes and schemes.

The walls are based on a tripartition by stone pillars in a giant order. At the corners there are eight doors of the same design, now true and now false: the frames are surmounted by an aedicule resting on a shelf supported by volutes, which coincides with the architrave; they are crowned by circular tympanums resting on small pillars which are close together towards the inside. In each aedicule a double panel opens, the upper line of which touches the tympanum, creating a lively interplay of lines. Inside, instead of the statues or bronze reliefs perhaps foreseen in the original project, there are festoons in relief and a patera.

At the center of these side elements that recur throughout the walls are the scarsella, on the side of the altar, the unfinished tomb of the "Magnificent" and the two tombs of the "Dukes" on the side walls. The latter, above the simple mirrors profiled in the lower half, present an internal tripartition in the median band, in which we see the rectangular niche with the statue of the deceased in the center and on the sides, divided by paired marble pillars, two niches with an arched tympanum on shelves resting on the frame, which resume, simplifying it, the design of the niches above the portals. The tombs therefore fit into the walls by interacting with the architecture, rather than simply leaning against it. Further up, the lower entablature, present only on the sides of the tombs, shows festoons in relief above the tympanums, balustrades on which the cornice can be pronounced over the pillars, and in the center a flat band enlivened by a central volute, citing the Roman arches. Above, the entablature in sandstone runs along the entire perimeter of the space, on which runs a smooth white frieze and a second molded stone frame. The central arch of the wall, one third of the surface wide, and small pillars in pietra serena that still divide the space into three sections are set on it. Above the arch some recessed compartments create a refined play of light; on the sides of this band, aligned with the portals, are the stone windows, with a developed triangular tympanum, creating the effect of tapering and therefore of upward acceleration.

Sculptures

Embedded in the two side walls are the monumental tombs of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours, and Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino. Initially up to five sculptures per tomb were to be carved, but the number was ultimately reduced to three. For the funerary monuments on both sides of the chapel, Michelangelo created the Allegories of Time, which symbolize the triumph of the Medici family over the passage of time. The four Allegories are placed above the sepulchers, at the feet of the dukes. The elliptical line on which they rest is an invention by Michelangelo that anticipates the curves of the Baroque, as in the staircase of the Laurentian Library. For the tomb of Giuliano de' Medici, he chose the Day and the Night for that of Lorenzo the Dusk (or Twilight) and the Dawn. The four Rivers, never executed, were also intended to recall the permanent and unstoppable flow of time.[2]

All the Allegories are characterized by stretching and twisting and appear "unfinished" in some parts. Particularly beautiful are the emblematic position of the Day, turned from the back which shows only the mysterious expression of the eyes in a barely sketched face, or the body of the Night which perfectly represents abandonment during sleep. In the Renaissance, especially in environments influenced by the Florentine Neoplatonism of Marsilio Ficino, the Night rediscovers its attributes of Primordial Mother and is associated with the figure of Leda. The position of the goddess, with her head bowed, expresses the kinship of the Night with the melancholic temperament. The owl and the poppies are symbols of Death and Sleep, the twin sons of Night. According to the doctrines of Orphism and Pythagoreanism, Leda and the Night are the personification of a double theory of death, according to which joy and pain coincide.[4] The Dawn, then, seems caught in the act of waking up and realizing, with pain, that Lorenzo's eyes are closed forever. The female figures have masculine features, such as broad shoulders or muscular hips, which they have in common with those on the Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome. The male body in movement is in fact the recurring subject of Michelangelo's oeuvre, even when it comes to portraying women.

All four allegorical sculptures are Neoplatonic in the Plotinian sense, in the sense of the unfinished. The portraits of Lorenzo and Giuliano that dominate the tombs, on the other hand, are ideal portraits, Neoplatonic in their perfect execution.

As for the portraits of the dukes, Michelangelo sculpted them seated in two niches above their respective tombs, facing each other, both dressed as Roman leaders. These sculptures, with attention to the smallest details, are idealized and do not reproduce real features, but nonetheless have a strong psychological character (Giuliano sitting in a proud posture with the baton of command is more haughtier and decisive, while Lorenzo, in a thoughtful pose, is more melancholic and meditative). A popular tradition tells that someone criticized the lack of resemblance of the portrait to the true features of Giuliano; Michelangelo, aware that his work would be handed down over time, replied that in ten centuries no one would be able to notice. Giuliano personifies active life, one of the two roads that lead to God. His scepter alludes to royal power, characteristic of those born under the sign of Jupiter. The coins are a symbol of magnanimity and indicate that the active man loves to "expend" himself in action. Lorenzo, known by the name "pensive", represents the contemplative attitude. The shadowed face recalls the facies nigra of Saturn, protector of melancholics. The forefinger on the mouth traces the saturnine motif of silence. The reclining arm is an iconographic tope of the melancholy mood. The closed casket resting on a leg is an allusion to parsimony, a typical quality of saturnine temperaments.[4]

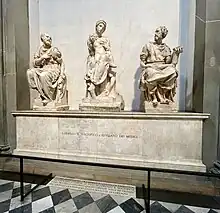

Lorenzo the Magnificent and Giuliano de' Medici

The sepulcher with the mortal remains of Lorenzo the Magnificent (died in 1492) and his brother Giuliano (killed during the Pazzi Conspiracy in 1478) is surmounted by three sculptures. In the center is Michelangelo's statue of Madonna and Child (known as the Medici Madonna), completed in 1521. The Madonna is flanked by the two patron saints of the Medici family: on the right Saint Cosmas, executed by the Florentine sculptor Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli in 1537, and on the left Saint Damian, by the sculptor and architect Raffaello da Montelupo in 1531, who began working with Michelangelo on the Sagrestia Nuova at an early age. Saint Cosmas is also attributed to Montelupo, together with Montorsoli, another assistant to Michelangelo, after a model by the master.[5][6]

The three statues were later placed by Giorgio Vasari on a simple marble chest housing the remains of Lorenzo the Magnificent and his brother Giuliano de' Medici, for whom there was never the time to build a larger monumental tomb.[5]

Graffiti

On the walls of the scarsella is a series of graffitied figures and architectural motifs, referring to Michelangelo's assistants. A trap door in the room to the left of the altar leads to another small barrel-vaulted room, where the artist could retire in solitude. On the walls of this room a large number of graffiti drawings referable to Michelangelo himself were found.[7] From November 2023 the chamber will be open to visitors, who will be limited to four at a time for reasons of conservation.[8]

Gallery

_Cappelle_Medicee_Firenze.jpg.webp) Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino

Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino_Cappelle_Medicee_Florenz-3.jpg.webp) Dusk

Dusk_Cappelle_Medicee_Florenz-4.jpg.webp) Dawn

Dawn_Cappelle_Medicee_Florenz-4.jpg.webp)

%252C_The_Sagrestia_Nuova_at_the_Medici_Chapel.jpg.webp) Night

Night%252C_The_Sagrestia_Nuova_at_the_Medici_Chapel.jpg.webp) Day

Day

River God

River God

Other sculptures related to the New Sacristy

- River God, Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence (c. 1524)

- Crouching Boy Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg (c. 1524)

See Also

References

- ↑ "Medici Chapels and Church of San Lorenzo". The Museums of Florence. Florence, Italy. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Baldini, Umberto (1982). The sculpture of Michelangelo. Rizzoli. pp. 84, 100–101. ISBN 9780847804474.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 Gonzáles, Marta Alvarez (2008). Michelangelo. Mondadori arte. pp. 27, 29. ISBN 978-88-370-6434-1. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- 1 2 Battistini, Matilde (2005). Symbols and Allegories in Art. Getty Publications. pp. 69, 332–333. ISBN 9780892368181. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 Wilson, Charles Heath (1881). Life and Works of Michelangelo Buonarroti. p. 263. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ↑ "Montórsoli, Giovanni Angelo (in Italian)". Institute of the Italian Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 7 June 2023.

- ↑ "Michelangelo's secret room". Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2023.

- ↑ Giuffrida, Angela (31 October 2023). "Michelangelo's secret sketches under church in Florence open to public". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

External links

- 500 years of the New Sacristy: Michelangelo in the Medici Chapel by Peter Barenboim (with Heath, Arthur)

%252C_San_Lorenzo%252C_Florence_(2)_(cropped).jpg.webp)