| History of Puerto Rico |

|---|

|

|

The recorded military history of Puerto Rico encompasses the period from the 16th century, when Spanish conquistadores battled native Taínos in the rebellion of 1511, to the present employment of Puerto Ricans in the United States Armed Forces in the military campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Puerto Rico was part of the Spanish Empire for four centuries, during which the people of Puerto Rico defended themselves against invasions from the British, French, and Dutch. Puerto Ricans fought alongside General Bernardo de Gálvez during the American Revolutionary War in the battles of Baton Rouge, Mobile, Pensacola and St. Louis. During the mid-19th century, Puerto Ricans residing in the United States fought in the American Civil War.[1] In the 1800s, the quest for Latin American independence from Spain spread to Puerto Rico, in the short-lived revolution known as the Grito de Lares and culminating with the Intentona de Yauco. The island was invaded by the United States during the Spanish–American War. After the war ended, Spain officially ceded the island to the United States under the terms established in the Treaty of Paris of 1898. Puerto Rico became a United States territory and the "Porto Rico Regiment" (Puerto Rico's name was changed to Porto Rico) was established on the island.

Upon the outbreak of World War I, the U.S. Congress approved the Jones–Shafroth Act, which extended United States citizenship (the Puerto Rican House of Delegates rejected US citizenship)[2] with limitations upon Puerto Ricans and made them eligible for the military draft. Since then, as citizens of the United States, Puerto Ricans have participated in every major United States military engagement.

During World War II, Puerto Ricans participated in the Pacific and Atlantic theaters, not only as combatants but also as commanders. It was during this conflict that Puerto Rican nurses were allowed to participate as members of the WAACs. Four Puerto Ricans were awarded the Medal of Honor, the highest military honor in the United States, for their actions during the Korean War. The members of Puerto Rico's 65th Infantry Regiment distinguished themselves in combat in the Korean War and were honored with the Congressional Gold Medal.[3] During the Vietnam War five Puerto Ricans were awarded the Medal of Honor. Presently, Puerto Ricans continue to serve in the military of the United States.

Taíno rebellion of 1511

Christopher Columbus arrived in the island of Puerto Rico on November 19, 1493, during his second voyage to the so-called "New World". The island was inhabited by the Arawak group of Indigenous peoples known as Tainos, who called the island "Borikén" or "Borinquen".[4] Columbus named the island San Juan Bautista in honor of Saint John the Baptist. The main port was named Puerto Rico (Rich Port) (eventually the island was renamed Puerto Rico and the port which was to evolve into the capital of the island was renamed San Juan). The conquistador Juan Ponce de León accompanied Columbus on this trip.[5]

.jpg.webp)

When Ponce de León arrived in Puerto Rico, he was well received by the Cacique (Tribal chief) Agüeybaná (The Great Sun), chieftain of the island Taino tribes. Besides the conquistadors, some of the first colonists were farmers and miners in search of gold. In 1508, Ponce de León became the first appointed governor of Puerto Rico, founding the first settlement of Caparra between the modern-day cities of Bayamón and San Juan. After being named Governor, de León and the conquistadors forced the Tainos to work in the mines and to build fortifications; many Tainos died as a result of cruel treatment during their labor. In 1510, upon Agüeybaná's death, his brother Güeybaná, better known as Agüeybaná II (The Brave), and a group of Tainos led Diego Salcedo, a Spaniard, to a river and drowned him, proving to his people that the white men were not gods. Upon realizing this, Agüeybaná II led his people in the Taino rebellion of 1511, the first rebellion in the island against the better armed Spanish forces. Guarionex, cacique of Utuado, attacked the village of Sotomayor (present-day Aguada) and killed eighty of its inhabitants.[6] Cacique Guarionex died during the attack which was considered a Taino victory.[7]

After the Taino victory, the colonists formed a citizens' militia to defend themselves against the attacks. Juan Ponce de León and one of his top commanders, Diego de Salazar, led the Spaniards in a series of offensives which included a massacre of the Taino forces in the domain of Agüeybaná II. The Spanish offensive culminated in the Battle of Yagüecas against Cacique Mabodomoca.[8] Agüeybaná II was shot and killed, ending the first recorded military action in Puerto Rico.[9] After the failed rebellion, the Tainos were forced to give up their customs and traditions by order of a Royal decree, approved by King Ferdinand II, which required that they adopt and practice the values, religion and language of their conquerors.[7]

European powers fight over Puerto Rico

16th century

Puerto Rico was considered the "Key to the Caribbean" by the Spanish because of its location as a way station and port for Spanish vessels.[10] In 1540, with revenue from Mexican mines, the Spanish settlers began the construction of Fort San Felipe del Morro ("the promontory") in San Juan. With the completion of the initial phase of the construction in 1589 El Morro became the island's main military fortification, guarded by professional soldiers. The rest of Puerto Rico, which had been reorganized in 1580 as the Captaincy General of Puerto Rico,[11] had to rely on only a handful of soldiers and the local volunteer militia to defend the island against militant and pirate attacks.

The main enemies of Spain at the time were the English and the Dutch. They, however were not the only enemies that Spain faced in the Caribbean during this period. On October 11, 1528, the French sacked and burned the settlement of San Germán during an attempt to capture the island, destroying many of the island's first settlements—including Guánica, Sotomayor, Daguao and Loiza—before the local militia forced them to retreat. The only settlement that remained was San Juan.[12]

In 1585, war broke out between England and Spain—extending to Spanish and English territories in the Americas. In November 1595, Sir Francis Drake and Sir John Hawkins attempted an unsuccessful invasion of San Juan. On June 15, 1598, the English fleet, led by George Clifford,[13] landed in Santurce and held the island for 157 days. He was forced to abandon the island upon an outbreak of bacillary dysentery among his troops, losing 700 men to the outbreak.[14] On December 26, 1598, Alonso de Mercado, a military man was named to the Captaincy General of Puerto Rico by Spain and asked to punish anyone who had allowed the takeover, through negligence, malice or cowardice.[15]

17th century

The Dutch Republic was a world military and commercial power by 1625, competing in the Caribbean with the English. The Dutch wanted to establish a military stronghold in the area, and dispatched Captain Boudewijn Hendricksz (also known as Boudoyno Henrico or Balduino Enrico) to capture Puerto Rico. On September 24, 1625, Enrico arrived at the coast of San Juan with 17 ships and 2,000 men. Enrico sent a message to the governor of Puerto Rico, Juan de Haro, ordering him to surrender the island. De Haro refused; he was an experienced military man and expected an attack in the section known as Boqueron. He therefore had that area fortified. However, the Dutch took another route and landed in La Puntilla.[12]

De Haro realized that an invasion was inevitable and ordered Captain Juan de Amézqueta and 300 men to defend the island from El Morro Castle and then had the city of San Juan evacuated. He also had former governor Juan de Vargas organize an armed resistance in the interior of the island. On September 25, Hendricksz attacked San Juan, besieging El Morro Castle and La Fortaleza (the Governor's Mansion). He invaded the capital city and set up his headquarters in La Fortaleza. The Dutch were counterattacked by the civilian militia on land and by the cannons of the Spanish troops in El Morro Castle. The land battle left 60 Dutch soldiers dead and Hendricksz with a sword wound to his neck which he received from the hands of Amézqueta.[16] The Dutch ships at sea were boarded by Puerto Ricans, who defeated those aboard. After a long battle, the Spanish soldiers and volunteers of the city's militia were able to defend the city from the attack and save the island from an invasion. On October 21, Hendricksz set La Fortaleza and the city ablaze. Captains Amézqueta and Andrés Botello decided to put a stop to the destruction and led 200 men in an attack against the enemy's front and rear guard. They drove Hendricksz and his men from their trenches and into the ocean in haste to reach their ships.[17][18] Hendricksz upon his retreat left behind him one of his largest ships, stranded, and over 400 dead.[17] He then tried to invade the island by attacking the town of Aguada. He was again defeated by the local militia and abandoned the idea of invading Puerto Rico.[12][18]

In 1693, the Milicias Urbanas de Puerto Rico were organized in almost every town. Every native male, aged between 16 and 60, was obliged to serve in these companies, unless he had an official exemption on account of physical disability or family hardship.[19]

While Spain and England were in a power struggle in the New World, Puerto Rican privateering of English ships was encouraged by the Spanish Crown. Captain Miguel Enríquez and Captain Roberto Cofresí (in the 19th century) were two of the most famous Puerto Rican privateers. In the first half of the 18th century, Henriquez, a shoemaker by occupation, decided to try his luck as a privateer. He showed great valor in intercepting English merchant ships and other ships dedicated to contraband that were infesting the seas of Puerto Rico and the Atlantic Ocean in general. Henriquez organized an expeditionary force which fought and defeated the English in the island of Vieques. He was received as a national hero when he returned the island of Vieques to the Spanish Empire and to the governorship of Puerto Rico. In recognition of his service, the Spanish Crown awarded Henriquez the Medalla de Oro de la Real Efigie ("The Gold Medal of the Royal Effigy"), named him "Captain of the Seas and War", and gave him a letter of marque and reprisal, thus granting him the privileges of privateer.[20]

18th century

Armed conflicts with the British

The English continued their attacks against Spanish colonies in the Caribbean, taking minor islands including Vieques east of Puerto Rico. On August 5, 1702, the city of Arecibo, on Puerto Rico's northern coast, was invaded by the British. Armed only with spears and machetes, under the command of Captain Antonio de los Reyes Correa, 30 militia members defended the city from the English, who were armed with muskets and swords. The British were defeated, suffering 22 losses on land and 8 at sea. Reyes Correa was declared a national hero and was awarded the Medalla de Oro de la Real Efigie ("Gold Medal of the Royal Image") and the title of "Captain of Infantry" by King Philip V.[21]

Native-born Puerto Rican (criollos) had petitioned the Spanish Crown to serve in the regular Spanish army, resulting in the 1741 organization of the Regimiento Fijo de Puerto Rico. The Fijo served in the defense of Puerto Rico and other Spanish overseas possessions, performing in battles in Santo Domingo, other islands in the Caribbean, and South America, most notably in Venezuela. However, Puerto Rican complaints that the Fijo was being used to suppress the revolution in Venezuela caused the Crown to bring the Fijo home and in 1815 it was mustered out of service.[22]

In 1765, the Spanish Crown sent Field Marshal Alejandro O'Reilly to Puerto Rico to form an organized militia. O'Reilly, known as the "Father of the Puerto Rican Militia", oversaw training to bring fame and glory to the militia in future military engagements, nicknaming the civilian militia the "Disciplined Militia." O'Reilly was later appointed governor of colonial Louisiana in 1769 and became known as "Bloody O'Reilly."[23][24]

American Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, Spain lent the rebelling colonists the use of its ports in Puerto Rico, through which flowed financial aid and arms for their cause. An incident occurred in the coast of Mayagüez, in 1777, between two Continental Navy ships, the Eudawook and the Henry, and a Royal Navy warship, HMS Glasgow. Both American ships were chased by the larger and more powerful Glasgow. The American colonial ships were close to the coast of Mayagüez; members of the Puerto Rican militia of that town, realizing that something was wrong, signaled for the ships to dock at the town's bay. After the ships docked, the crews of both ships got off and some Mayagüezanos boarded and raised the Spanish flag on both ships. The commander of the Glasgow became aware of the situation and asked the island's governor, Jose Dufresne to turn over the ships. Dufresne refused and ordered the British warship out of the Puerto Rican dock.[25]

The governor of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvez, was named field marshal of the Spanish colonial army in North America. In 1779, Galvez and his troops, composed of Puerto Ricans and people from other Spanish colonies, distracted the British from the revolution by capturing Pensacola, the capital of the British colony of West Florida and the cities of Baton Rouge, St. Louis and Mobile. The Puerto Rican troops, under the leadership of Brigadier General Ramón de Castro,[26] helped defeat the British and Indian army of 2,500 soldiers and British warships in Pensacola.[27] Galvez and his multinational army also provided the Continental Army with guns, cloth, gunpowder and medicine shipped from Cuba up the Mississippi River. General Ramón de Castro, who was Galvez's Aide-de-camp in the Mobile and Pensacola campaigns, became the appointed governor of Puerto Rico in 1795.[28][29]

British attack Puerto Rico

On February 17, 1797, the governor of Puerto Rico Brigadier General Ramón de Castro, received news that Great Britain had invaded the island of Trinidad. Believing that Puerto Rico would be the next British objective he decided to put the local militia on alert and to prepare the island's forts against any military action. On April 17, 1797, British ships under the command of Sir Ralph Abercromby approached the coastal town of Loíza, to the east of San Juan. On April 18, British and Hessian troops landed on Loíza's beach.[30] Under the command of de Castro, British ships were shot at by artillery from both El Morro and the San Gerónimo fortresses but were beyond reach. After the invaders disembarked practically all fighting was land based with many skirmishes, field artillery and mortar fire exchanges between the San Gerónimo and San Antonio Bridge fortress and British emplacements in Condado to the East and El Olimpo hill in Miramar to the South. The British tried to take the San Antonio, a key passage to the San Juan islet, and repeatedly bombarded the nearby San Gerónimo almost demolishing it. At the Martín Peña Bridge, they were met by the likes of Sergeants José and Francisco Díaz and Colonel Rafael Conti who together with Lieutenant Lucas de Fuentes attacked the enemy with two cannons. After fierce fighting by the Spanish forces and local militia, they were defeated in all attempts to advance into San Juan. The invasion failed because Puerto Rican volunteers and Spanish troops fought back and defended the island in a manner described by a British lieutenant as of "astonishing bravery".

"La Rogativa" folklore

The defense of San Juan served as the base for the legend of "La Rogativa". According to the popular Puerto Rican legend, on the night of April 30, 1797, the townswomen, led by a bishop, formed a rogativa (prayer procession) and marched throughout the streets of the city singing hymns and carrying torches while at the same time praying for the deliverance of the city. Outside the walls, the invaders mistook the torch-lit movement for the arrival of Spanish reinforcements. When morning came, the enemy was gone from the island and the city was saved from a possible invasion. Four statues, sculptured by Lindsay Daen in the Plazuela de la Rogativa (Rogativa Plaza) in Old San Juan, pay tribute to the bishop and townswomen who participated in La Rogativa.[31][32]

Attack of Aguadilla

The British also attacked Aguadilla and Punta Salinas. They were defeated by Colonel Conti and the members of the militia in Aguadilla, and the British troops that had landed on the island were taken prisoner. The British retreated on April 30 to their ships and on May 2 set sail northward. Because of the defeat given to the British forces, governor Ramon de Castro petitioned Spanish King Charles IV for recognition for the victors; he was promoted to field marshal and several others were promoted and given pay raises.[12][33] The British persisted in invading Puerto Rico, after Abercromby's defeat, with unsuccessful skirmishes on the coastal towns of Aguadilla (December 1797), Ponce, Cabo Rojo, and Mayagüez. This continued to occur until 1802 when the Treaty of Amiens ended the War of the Second Coalition between European powers and Revolutionary France.[34]

19th century

France had threatened to invade the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo. In 1808, the Spanish Crown sent their Navy, under the command of Puerto Rican Captain Ramón Power y Giralt, to prevent the invasion of Santo Domingo by the French by enforcing a blockade. Col. Rafael Conti organized a military expedition with the intention of defending the Dominican Republic. They were successful and were proclaimed as heroes by the Spanish Government.[35]

San Juan native Demetrio O'Daly was a Sergeant Major in the Spanish Army when he participated in the 1809 Peninsular War, also known as the Spanish War of Independence, after the Napoleonic Invasion of 1808 and the kidnapping of both King Charles IV and Prince Ferdinand (later King Ferdinand VII). When King Ferdinand returned from exile and kidnapping, he repealed the Constitution of 1812, which as the rest of European monarchs, he felt was a Napoleonic maneuver to weaken the countries. But O'Daly was a defender of the Spanish Constitution of 1812 and was considered a rebel and exiled from Spain by King Fernando VII in 1814. In 1820 O'Daly, a liberal constitutionalist, together with fellow rebel Col. Rafael Riego organized and led the Revolt of the Colonels. It was not a revolt against the king, but a revolt to force him reinstate the constitution which was successful. This was called the Trienio Liberal/Liberal Three years (1820–23). During this process O'Daly was promoted to field marshal and awarded the Cruz Laureada de San Fernando (Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand), the highest military decoration awarded by the Spanish government.[36][37]

American Civil War

During the 1800s, commerce existed between the ports of the eastern coast of the United States and Puerto Rico. Ship records show that many Puerto Ricans traveled on ships that sailed to and from the U.S. and Puerto Rico. Many of them settled in places such as New York, Connecticut and Massachusetts. Upon the outbreak of the American Civil War, many Puerto Ricans joined the ranks of the United States military armed forces, however since Puerto Ricans were Spanish subjects they were inscribed as Spaniards. The 1860 census of New Haven, Connecticut, shows there were 10 Puerto Ricans living there. Among them was Augusto Rodriguez who joined the 15th Connecticut Regiment (a.k.a. Lyon Regiment) in 1862. During the Civil War, Rodriguez, who reached the rank of lieutenant, served in the defenses of Washington, D.C. He also led his men in the Battles of Fredericksburg and Wyse Fork. The regiment was mustered out on June 27, 1865, and he was discharged in New Haven on July 12, 1865.[1]

Slave revolts

Slavery was abolished in Puerto Rico in 1873, but the wealth amassed by many landowners in Puerto Rico through a plantation economy was generated by the exploitation of slaves. According to one source, this reliance on slavery "generated its antithesis—disobedience, uprisings and flights."[38]

In Puerto Rico, there were many minor slave revolts in which the slaves clashed with the military establishment. In July 1821, Marcos Xiorro, a bozal slave, planned and organized a conspiracy against the slave masters and the colonial government of Puerto Rico. According to his plot, which was to be carried out on July 27, during the festival celebrations for Santiago (St. James), several slaves were to escape from various plantations in Bayamón, which included the haciendas of Angus McBean, C. Kortnight, Miguel Andino and Fernando Fernández. They were then to proceed to the sugarcane fields of Miguel Figueres, and retrieve cutlasses and swords which were hidden in those fields.[39] Xiorro, together with a slave from the McBean plantation named Mario and another slave named Narciso, would lead the slaves of Bayamón and Toa Baja and capture the city of Bayamón. They would then burn the city and kill those who were not black. After this, they would all unite with slaves from the adjoining towns of Río Piedras, Guaynabo and Palo Seco. With this critical mass of slaves, all armed and emboldened from a series of quick victories, they would then invade the capital city of San Juan, where they would declare Xiorro as their king.[39]

Unfortunately for the slave conspirators, the plot was divulged by a fellow slave to the authorities. In response, the mayor of Bayamón mobilized 500 soldiers. The ringleaders and followers of the conspiracy were captured immediately. A total of 61 slaves were imprisoned in Bayamón and San Juan.[39] The ringleaders were executed and the fate of Xiorro remains a mystery.[39] There were other minor revolts up until the abolition of slavery in the island became official.[38]

Revolt against Spain

South America

In 1822, there was an attempt, known as the Ducoudray Holstein Expedition, conceived, carefully planned and organized by General Henri La Fayette Villaume Ducoudray Holstein to invade Puerto Rico and declare it a republic.[40]

This invasion was different from all its precursors since none before had intended to make Puerto Rico an independent nation, and use the Taino name "Boricua" as the official name of the republic, it was also intended more as a mercantile venture than a patriotic endeavor. It was the first time an invasion intended to make the city of Mayagüez the capital of the island.[40] However, plans of the invasion were soon disclosed to the Spanish authorities and the plot never materialized.

United Provinces of New Granada

In the early 19th century the Spanish colonies, in what is known as the Latin American wars of independence, began to revolt against Spanish rule. Antonio Valero de Bernabé was a Puerto Rican military leader known in Latin America as the "Liberator from Puerto Rico". Valero was a recent graduate of the Spanish Military Academy when Napoleon Bonaparte convinced King Charles IV of Spain to permit him to pass through Spanish soil with the sole purpose of attacking Portugal. When Napoleon refused to leave, the Spanish government declared war. Valero joined the Spanish Army and helped defeat Napoleon's army at the siege of Saragossa. Valero became a hero; he was promoted to the rank of colonel and was awarded many decorations.[41]

When Ferdinand VII assumed the throne of Spain in 1813, Valero became critical of the new king's policies towards the Spanish colonies in Latin America. He developed a keen hatred of the monarchy, resigned his commission in the army, and headed for Mexico. There he joined the insurgent army headed by Agustín de Iturbide, in which Valero was named chief of staff. He fought for and helped achieve Mexico's independence from Spain. After the Mexican victory, Iturbide proclaimed himself Emperor of Mexico. Since Valero had developed anti-monarchist feelings following his experiences in Spain, he revolted against Iturbide. His revolt failed and he attempted to escape from Mexico by way of sea.[41]

Valero was captured by a Spanish pirate, who turned him over to the Spanish authorities in Cuba. Valero was imprisoned but managed to escape with the help of a group of men that identified with Simón Bolívar's ideals. Upon learning of Bolívar's dream of creating a unified Latin America, including Puerto Rico and Cuba, Valero decided to join him. Valero stopped in St. Thomas, where he established contacts with the Puerto Rican independence movement.

He then traveled to Venezuela, where he was met by General Francisco de Paula Santander.[41] He next joined Bolívar and fought alongside "The Liberator" against Spain, gaining his confidence and admiration. Valero was named Military Chief of the Department of Panama, Governor of Puerto Cabello, Chief of Staff of Colombia, Minister of War and Maritime of Venezuela, and in 1849 was promoted to the rank of brigadier general.[42]

.jpg.webp)

The meetings of the Puerto Rican Independence movement which met in St. Thomas were discovered by the Spanish authorities and the members of the movement were either imprisoned or exiled. In a letter dated October 1, 1824, which Venezuelan rebel leader José María Rojas sent to María de las Mercedes Barbudo, Rojas stated that the Venezuelan rebels had lost their principal contact with the Puerto Rican Independence movement in the Danish island of Saint Thomas and therefore the secret communication which existed between the Venezuelan rebels and the leaders of the Puerto Rican independence movements was in danger of being discovered.[43]

Mercedes Barbudo, also known as the "first Puerto Rican female freedom fighter", was a businesswoman who became a follower of the independence ideal for Puerto Rico upon learning that Bolivar dreamed of eventually engendering an American Revolution-style federation, that would be known as the United Provinces of New Granada, between all the newly independent republics, with a government ideally set-up solely to recognize and uphold individual rights. She was involved with the Puerto Rican Independence Movement which had ties with the Venezuelan rebels led by Simón Bolívar and who were against Spanish colonial rule in Puerto Rico.[44]

Unknown to Mercedes Barbudo, the Spanish authorities in Puerto Rico under Governor Miguel de la Torre, were suspicious of the correspondence between her and the rebel factions of Venezuela. Secret agents of the Spanish Government had retained some of her mail and delivered it to Governor de la Torre. He ordered an investigation and had her mail confiscated. The Government believed that the correspondence served as propaganda of the Bolivian ideals and that it would also serve to motivate Puerto Ricans to seek their independence.[45] Governor Miguel de la Torre ordered her arrest on the charge that she planned to overthrow the Spanish Government in Puerto Rico. Since Puerto Rico did not have a women's prison she was held without bail at the Castillo San Cristóbal. Among the evidence which the Spanish authorities presented against her was Rojas letter. She was exiled to Cuba, where she was able to escape and make her way to Venezuela, where she spent her final days.[45]

Puerto Rico

The Spanish government had received many complaints from the nations whose ships were attacked by Puerto Rican pirate Captain Roberto Cofresí. Cofresí and his men had attacked eight ships, amongst them an American ship. The Spanish government, which routinely encouraged piracy against other nations, was pressured and felt obliged to pursue and capture the famous pirate. In 1824, Captain John Slout of the U.S. Naval Forces and his schooner USS Grampus engaged Cofresí in a fierce battle. The pirate Cofresí was captured, along with eleven of his crew members, and turned over to the Spanish Government. He was imprisoned in El Castillo del Morro in San Juan. Cofresi was judged by a Spanish Council of War, found guilty, and executed by firing squad on March 29, 1825.[46]

On April 13, 1855, a mutiny broke out among the artillerymen at Fort San Cristóbal. They were protesting an extended two years of military service imposed by the island's Spanish governor, Garcia Cambia. The mutineers pointed their cannons towards San Juan, creating a state of panic among the population. Upon their surrender, the governor had the eight men arrested and sentenced to death by firing squad.[47]

Grito de Lares

Many Spanish colonies had gained their independence by the mid-1850s. In Puerto Rico, there were two groups: the loyalists, who were loyal to Spain, and the independentistas, who advocated independence. In 1866, Dr. Ramón Emeterio Betances, Segundo Ruiz Belvis, and other independence advocates met in New York City where they founded the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico. An outcome of this venture was a plan to send an armed expedition from the Dominican Republic to invade the island. Several revolutionary cells were formed in the western towns and cities of Puerto Rico. Two of the most important cells were at Mayagüez, led by Mathias Brugman and code-named "Capa Prieto" and at Lares, code-named "Centro Bravo" and headed by Manuel Rojas. "Centro Bravo" was the main center of operations and was located in the Rojas plantation of El Triunfo. Manuel Rojas was named "Commander of the Liberation Army" by Betances. Mariana Bracetti (sister-in-law of Manuel) was named "Leader of the Lares Revolutionary Council." Upon the request of Betances, Bracetti knitted the first flag of Puerto Rico also known as the revolutionary Flag of Lares (Bandera de Lares).[48]

The Spanish authorities discovered the plot and were able to confiscate Betances's armed ship before it arrived in Puerto Rico. The Mayor of the town of Camuy, Manuel González (leader of that town's revolutionary cell), was arrested and charged with treason. He learned that the Spanish Army was aware of the independence plot, and escaped to warn Manuel Rojas. Alerted, the revolutionists decided to start the revolution as soon as possible, and set the date for September 28, 1868. Mathias Brugman and his men joined with Manuel Rojas's men and with about 800 men and women, marched on and took the town of Lares. This was to be known as "Grito de Lares" (The Cry of Lares) The revolutionists entered the town's church and placed Mariana Bracetti's revolutionary flag on the High Altar as a sign that the revolution had begun. They declared Puerto Rico to be the "Republic of Puerto Rico" and named Francisco Ramírez its President. Manuel and his poorly armed followers proceeded to march on to the town of San Sebastián, armed only with clubs and machetes. The Spanish Army had been forewarned, and awaited with superior firepower. The revolutionists were met with deadly fire. The revolt failed, many revolutionists were killed, and at least 475, including Manuel Rojas and Mariana Bracetti, were imprisoned in the jail of Arecibo and sentenced to death.[49][50]

Others fled and went into hiding. Mathias Brugman was hiding in a local farm where he was betrayed by a farmer named Francisco Quiñones; he was captured and executed on the spot. In 1869, fearing another revolt, the Spanish Crown disbanded the Puerto Rican Militia, which had been composed almost entirely of native-born Puerto Ricans, and also the Compañia de Artilleros Morenos de Cangrejos, a separate company of black Puerto Ricans. They then organized the Volunteer Institute, composed entirely of Spaniards and their sons.[51]

Intentona de Yauco

Leaders of El Grito de Lares who were in exile in New York City joined the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee, founded on December 8, 1895, to continue the quest for independence. In 1897, with the aid of Antonio Mattei Lluberas and Fidel Velez, the local leaders of the independence movement of the town of Yauco, they organized another uprising, which became known as the Intentona de Yauco. On March 26, 1897, there was a second and last major attempt to overthrow the Spanish government. The local conservative political factions, which believed that such an attempt would be a threat to their struggle for autonomy, opposed such an action. Rumors of the planned event spread to the local Spanish authorities, who acted swiftly and put an end to what would be the last major uprising in the island to Spanish colonial rule.[37]

Cuba

In 1869, the incoming governor of Puerto Rico, Jose Laureano Sanz, in an effort to ease tensions in the island, dictated a general amnesty and released all who were involved with the Grito de Lares revolt from prison. Both Mariana Bracetti and Manuel Rojas were released. Bracetti lived her last years in the town of Añasco, while Rojas was deported to Venezuela.[52] Many of the former prisoners joined the Cuban Liberation Army and fought against Spain. Among the many Puerto Ricans who volunteered to fight for Cuba's independence were Juan Ríus Rivera, Francisco Gonzalo Marín, also known as "Pachin Marín" and José Semidei Rodríguez.

Juan Ríus Rivera as a young man met and befriended Betances. He eventually joined the pro-independence movement in the island. He became a member of the Mayagüez revolutionary cell "Capá Prieto" under the command of Brugman. Ríus, did not participate directly in the revolt because at the time he was studying law in Spain, however, he was an avid reader about information pertaining to the Antilles and learned about the failed revolt. He interrupted his studies and traveled to the United States where he went to the Cuba Revolutionary "Junta" and offered his services. He joined the Cuban Liberation Army and was given the rank of general and fought alongside Gen. Máximo Gómez in Cuba's Ten Years' War. He later fought alongside Gen. Antonio Maceo Grajales and upon Maceo's death was named Commander-in-Chief of the Cuban Liberation Army. After Cuba gained its independence, Gen. Juan Ríus Rivera became an active political figure in the new nation.[53]

Francisco Gonzalo Marín was a poet and journalist in Puerto Rico who joined the Cuban Liberation Army upon learning of the death of his brother Wecenlao in the battlefields of Cuba. Marin, who was given the rank of lieutenant, befriended and fought alongside José Martí. In November 1897, Lt. Marin died from the wounds he received in a skirmish against the Spanish Army.[54]

José Semidei Rodríguez from Yauco, Puerto Rico, fought in various battles in the Cuban War of Independence (1895–1898). After Cuba gained its independence he joined the Cuban National Army with the rank of brigadier general. Semidei Rodríguez continued to serve in Cuba as a diplomat upon his retirement from the military.[55]

Spanish–American War

In 1890, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, a member of the Navy War Board and leading U.S. strategic thinker, wrote a book titled The Influence of Sea Power upon History where he argued for the creation of a large and powerful navy modeled after the British Royal Navy. Part of his strategy called for the acquisition of colonies in the Caribbean Sea which would serve as coaling and naval stations and which would serve as strategic points of defense upon the construction of a canal in the Isthmus.[56]

This was not a new idea: William H. Seward, the former Secretary of State under the administrations of various presidents, among them Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses Grant, had stressed that a canal be built either in Honduras, Nicaragua or Panama and that the United States annex the Dominican Republic and purchase Puerto Rico and Cuba. The idea of annexing the Dominican Republic failed to receive the approval of the U.S. Senate and Spain did not accept the 160 million dollars the U.S. offered for Puerto Rico and Cuba.[56]

Since 1894 the Naval War College had been formulating plans for war with possible adversaries. One of these plans included military operations in Puerto Rican waters. Not only was Puerto Rico considered valuable as a naval station, Puerto Rico and Cuba were also major producers of sugar, a valuable commercial commodity the United States lacked.[57]

The United States declared war on Spain in 1898 following the loss of the battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor, Cuba. One of the United States' principal objectives in the Spanish–American War was to take control of Spanish possessions Puerto Rico and Cuba in the Atlantic, and the Philippines and Guam in the Pacific.[58]

.

The Spanish sent the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Puerto Rican Provisional Battalions to defend Cuba against the American invaders. The 1st Puerto Rican Provisional Battalion, composed of the Talavera Cavalry and Krupp artillery, was sent to Santiago de Cuba where they fought American forces in the Battle of San Juan Hill. The Puerto Rican Battalion suffered a total of 70% casualties including dead, wounded, MIAs and prisoners.[59]

The invasion of Puerto Rico by the American military forces was known as the Puerto Rican Campaign. On May 10, 1898, Spanish forces under the command of Captain Ángel Rivero Méndez in the fortress of San Cristóbal in San Juan, exchanged fire with the USS Yale, and on May 12 a fleet of 12 American ships bombarded San Juan.[60] On June 25, the USS Yosemite arrived in San Juan and blockaded the port. Captains Ramón Acha Caamaño and José Antonio Iriarte, both natives of Puerto Rico, were among those who defended the city from Fort San Felipe del Morro. They had three batteries under their command, which were armed with at least three 15 cm Ordóñez cannons. The battle lasted three hours and resulted in the death of Justo Esquivies, the first Puerto Rican soldier to die in the Puerto Rican Campaign.[60]

On July 25, General Nelson A. Miles landed at the southern town of Guánica and began advancing towards Ponce and then San Juan.[61]

One of the most notable battles during the Puerto Rico Campaign occurred between combined Spanish forces and Puerto Rican volunteers, led by Captain Salvador Meca and Lieutenant Colonel Francisco Puig, and American forces led by Brigadier General George A. Garretson on July 26, 1898. The Spanish forces engaged the 6th Massachusetts in the Battle of Yauco. Puig and his forces suffered 2 officers and 3 soldiers wounded and 2 soldiers dead. The Spanish forces were ordered to retreat.[62]

The Puerto Rican Campaign was short compared to the other campaigns because the Puerto Ricans who resided in the southern and western towns and villages resented Spanish rule and tended to view the Americans as their liberators, thereby making the invasion much easier. The 1st, 2nd and 3rd Puerto Rican Provisional Battalions were in Cuba defending that island, which may have also contributed. However, the Americans met resistance from the Spanish forces and Puerto Rican Volunteers and were engaged in the following battles: Battle of Fajardo, Battle of Guayama, Battle of the Guamani River Bridge, Battle of Coamo, Battle of Silva Heights and Battle of Asomante.[62] On August 13, 1898, the Spanish–American War ended and the Spanish surrendered without other major incidents. Some Puerto Rican leaders such as José de Diego and Eugenio María de Hostos expected the United States to grant the island its independence.[63][64] Believing that Puerto Rico would gain its independence, a group of men staged an uprising in Ciales which became known as "El Levantamiento de Ciales" or the "Ciales Uprising of 1898" and proclaimed Puerto Rico to be a republic. The Spanish authorities who were unaware that the cease fire had been signed brutally suppressed the uprising.[65] The total casualties of the Puerto Rican Campaign were 450 dead or wounded Spanish and Puerto Ricans, and 4 dead and 39 wounded Americans.[66]

Upon the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, Puerto Rico became a territory of the United States. The Spanish troops had already left by October 18, and the United States named General Nelson A. Miles military governor of the island. On July 1, 1899, "The Porto Rico Regiment of Infantry, United States Army" was created, and approved by the U.S. Congress on May 27, 1908. The regiment was a segregated, all-volunteer unit made up of 1,969 Puerto Ricans.[66]

Puerto Rican commander in the Philippines

In 1897, before the onset of fighting in Puerto Rico, Juan Alonso Zayas, born in San Juan, was a second lieutenant in the Spanish Army when he received orders to head for the Philippines to take command of the 2nd Expeditionary Battalion stationed in Baler. He arrived in Manila, the capital, in May 1897. There, he took a vessel and headed for Baler, on the island of Luzon. The distance between Manila and Baler is 62 miles (100 km); if traveled through the jungles and badly built roads, the actual distance was 144 miles (230 km). At that time a system of communication between Manila and Baler was almost non-existent. The only way Baler received news from Manila was by way of vessels. The Spanish colonial government was under constant attack from local Filipino groups who wanted independence. Zayas's mission was to fortify Baler against any possible attack. Among his plans for the defense of Baler was to convert the local church of San Luis de Tolosa into a fort.[67][68]

The independence advocates, under the leadership of Colonel Calixto Vilacorte, were called "insurgents" (Tagalos) by the Spanish. On June 28, 1898, they demanded the surrender of the Spanish army. The Spanish governor of the region, Enrique de las Morena y Fossi, refused. The Filipinos immediately attacked Baler in a battle that was to last for seven months. Despite being outnumbered and suffering hunger and disease, the battalion did not capitulate. In the meantime, Zayas and the rest of the battalion were totally unaware of the Spanish–American War. In August, 1898, hostilities between the United States and Spain came to an end. The Philippines became a U.S. possession in accordance with the Treaty of Paris. In May, 1899, the battalion at Baler learned of the Spanish–American War and its aftermath. On June 2, 1899, the battalion's commander, Lieutenant Martín Cerezo, surrendered to the Tagalos. The surrender was dependent upon several conditions, including the Spaniards not being treated as prisoners of war and being allowed to travel to a ship that would take them back to Spain. The 32 survivors of Zayas Battalion were sent to Manila, where they boarded a ship for Spain. In Spain, they were given a hero's welcome and became known as los Ultimos de Baler—"the Last of Baler".[68]

Puerto Rico Provisional Regiment of Infantry

On March 2, 1898, Congress authorized the creation of the first body of native troops in Puerto Rico. On June 30, 1901, the "Porto Rico Provisional Regiment of Infantry" came into being. An Act of Congress, approved on May 27, 1908, reorganized the regiment as part of the "regular" Army. Since the native Puerto Rican officers were Puerto Rican citizens and not citizens of the United States, they were required to undergo a new physical examination to determine their fitness for commissions in the Regular Army and to take an oath of U.S. citizenship with their new officers oath.[69]

Puerto Rico National Guard

In 1906, a group of Puerto Ricans met with the appointed Governor Winthrop, and suggested the organization of a Puerto Rico National Guard. The petition failed because the U.S. Constitution prohibits the formation of any armed force within the United States and its territories without the authorization of Congress.

On June 19, 1915, Major General Luis R. Esteves of the U.S. Army became the first Puerto Rican and the first Hispanic to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. While he attended West Point, he tutored classmate Dwight D. Eisenhower in Spanish; a second language was required in order to graduate. He was a second lieutenant in the 8th Infantry Brigade under the command of John J. Pershing when he was sent to El Paso, Texas, in the Pancho Villa Expedition. From El Paso, he was sent to the town of Polvo, where he was appointed mayor and judge by its citizens. Esteves helped organize the 23rd Battalion, which would be composed of Puerto Ricans and be stationed in Panama during World War I. He also played a key role in the formation of the Puerto Rico National Guard.[70]

World War I

In 1904, Camp Las Casas was established in Santurce under the command of Lt. Colonel Orval P. Townshend. The Porto Rico Regiment was assigned to the camp. The regiment consisted of two battalions of the former Porto Rico Provisional Regiment of Infantry.[71]

Lieutenant Teófilo Marxuach was the officer of the day at El Morro Castle on March 21, 1915. The Odenwald, built in 1903 (not to be confused with the German World War II war ship which carried the same name), was an armed German supply ship which tried to force its way out of the San Juan Bay and deliver supplies to the German submarines waiting in the Atlantic Ocean. Lt. Marxuach gave the order to open fire on the ship from the walls of the fort. Sergeant Encarnacion Correa manned a machine gun and fired warning shots with little effect.[37] Marxuach fired a shot from a cannon located at the Santa Rosa battery of "El Morro" fort, in what is considered to be the first shot of World War I fired by the regular armed forces of the United States against any ship flying the colors of the Central Powers,[72] forcing the Odenwald to stop and to return to port where its supplies were confiscated. The Odenwald was confiscated by the United States and renamed SS Newport. It was assigned to the U.S. Shipping Board, where it served until 1924 when it was retired.[73]

Lt. Teófilo Marxuach pictured on top row, fifth L–R.

As more countries became involved in World War I, the U.S. Congress approved the Jones–Shafroth Act, which imposed United States citizenship upon Puerto Ricans.[74] Those who were eligible, with the exception of women, were expected to serve in the military. About 20,000 Puerto Ricans were drafted during World War I.[75] On May 3, 1917, the regiment recruited 1,969 men. The 295th and 296 Infantry Regiments were created in Puerto Rico.[76] In November 1917, the first military draft (conscription) lottery in Puerto Rico was held in the island's capital, San Juan. Eustaquio Correa was the first Puerto Rican to be drafted into the Armed Forces of the United States.[77]

On May 17, 1917, the Porto Rico Regiment of Infantry was deployed to guard the Panama Canal.[78] One of the Puerto Ricans who distinguished himself during World War I was Lieutenant Frederick Lois Riefkohl of the US Navy, who on August 2, 1917, became the first known Puerto Rican to be awarded the Navy Cross. The Navy Cross was awarded to Lt. Riefkohl for his actions in an engagement with an enemy submarine. Lt. Riefkohl, who was also the first Puerto Rican to graduate from the United States Naval Academy, served as a rear admiral in World War II.[79]

Frederick L. Riefkohl's brother, Rudolph William Riefkohl also served. Riefkohl was commissioned a second lieutenant and assigned to the 63rd Heavy Artillery Regiment in France, where he participated in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. According to the United States War Department, after the war he served as Captain of Coastal Artillery at the Letterman Army Medical Center in Presidio of San Francisco, in California (1918). He played an instrumental role in helping the people of Poland overcome the 1919 typhus epidemic.[80]

By 1918, the Army realized there was a shortage of physicians specializing in anesthesia, a low salary specialty, who were required in military operating rooms. To address the need, the Army began hiring women physicians as civilian contract employees. The first Puerto Rican woman doctor to serve in the Army under contract was Dr. Dolores Piñero from San Juan. She was assigned to the San Juan base hospital where she worked as an anesthesiologist during the mornings and in the laboratory during the afternoons.[81]

In New York, some Puerto Ricans joined the 369th Infantry Regiment,[82] which was mostly composed of African-Americans. They were not allowed to fight alongside their white counterparts, but did serve as part of a French division. They fought on the Western Front in France, and their reputation earned them the nickname of "the Harlem Hell Fighters" by the Germans.[83] Among them was Rafael Hernández Marín, considered by many as Puerto Rico's greatest composer.[84] The 369th was awarded French Croix de guerre for battlefield gallantry by the French government.[83]

On January 6, 1914, First Lieutenant Bernard L. Smith established the Marine Section of the Navy Flying School in the island municipal Culebra.[85] As the number of Marine Aviators grew so did the desire to separate from Naval Aviation.[86] The Marine Corps Aviation Company in Puerto Rico consisted of 10 officers and 40 enlisted men.[87]

The Porto Rico Regiment returned to Puerto Rico in March 1919 and was renamed the 65th Infantry Regiment under the Reorganization Act of June 4, 1920.[71] It is estimated that 18,000 Puerto Ricans from the Porto Rico Regiment served in the war and that 335 were wounded by chemical gas experimentation the United States conducted as part of its active chemical weapons program in Panama.[88] Neither the military nor the War Department of the United States kept statistics in regard to the total number of Puerto Ricans who served in the regular units of the Armed Forces (United States mainland forces). It is known that four Puerto Ricans died in combat, but it is impossible to determine the exact number of Puerto Ricans who served and died in World War I.

The need for a Puerto Rican National Guard unit became apparent to Major General Luis R. Esteves, who had served as an instructor of Puerto Rican Officers for the Porto Rico Regiment of Infantry at Camp Las Casas in Puerto Rico. His request was approved by the government and Puerto Rican Legislature. In 1919, the first regiment of the Puerto Rican National Guard was formed, and General Luis R. Esteves became the first official Commandant of the Puerto Rican National Guard.[89][90]

Interwar years

Second Nicaraguan Campaign (1926–1933)

After World War I, Puerto Ricans fought on foreign shores as members of the United States Marine Corps. Civil war broke out in Nicaragua during the first months of 1926, and upon the request of the Nicaraguan government, 3,000 U.S. Marines were sent ashore to establish a neutral zone for the protection of American citizens.[91] The American intervention was also known as the Banana Wars.

In 1926, Captain Pedro del Valle served with the Gendarmerie of Haiti for three years. During that time he also became active in the war against Augusto Sandino in Nicaragua. In 1927, Lieutenant Jaime Sabater, from San Juan, Puerto Rico, graduated from United States Naval Academy.[92]

Private Rafel Toro, from Humacao, Puerto Rico, was part of the U.S. Marine Corps occupation force in Nicaragua, serving with the Guardia Nacional de Nicaragua. On July 25, 1927, Private Toro was assigned to advance guard duty in Nueva Segovia. As he rode into town, he was attacked; returning fire, he was able to hold back the enemy until reinforcements arrived. He was mortally wounded in this action and was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross.[93]

Rif War (1920)

After the Spanish–American War, members of the Spanish forces and civilians who were loyal to the Spanish Crown were allowed to return to Spain. Those who returned took with them their Puerto Rican spouses and children. Among those who were born in Puerto Rico and who would go on to serve in the Rif War as members of the Spanish military were General Manuel Goded Llopis and Captain Felix Arenas Gaspar. The Rif War was a rebellion against Spanish colonial rule in Spanish Morocco, a Spanish protectorate, in 1919.[94] During the Rif War Gaspar, who was born in San Juan, distinguished himself in combat. He was posthumously awarded the Cruz Laureada de San Fernando "Laureate Cross of Saint Ferdinand" (Spain's version of the United States' Medal of Honor) for his actions in the defense of his company.[95]

Spanish Civil War (1936–1939)

Puerto Ricans fought on both sides during the Spanish Civil War. The Spanish Civil War was a major conflict in Spain that started after an attempted coup d'état by parts of the army, led by the Fascist General Francisco Franco, against the government of the Second Spanish Republic. Puerto Ricans fought on both of the factions involved; the "Nationalists" as members of the Spanish Army and the "Loyalists" (Republicans) as members of the Abraham Lincoln International Brigade.[95]

Among the Puerto Ricans who fought alongside General Franco and the Nationalists was General Manuel Goded Llopis (1882–1936). Llopis, who was born in San Juan, was named Chief of Staff of the Spanish Army of Africa after his victories in the Rif War, took the Balearic Islands and by order of Franco, suppressed the rebellion of Asturias. Llopis was sent to lead the fight against the Anarchists in Catalonia, but his troops were outnumbered. He was captured and was sentenced to die by firing squad.[96][97]

Among the many Puerto Ricans who fought for the Second Spanish Republic as members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade was Lieutenant Carmelo Delgado Delgado (1913–1937), a leader of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party from Guayama. At the start of the Spanish Civil War Delgado was in Spain studying for a law degree. Delgado was an anti-fascist who believed the Spanish Nationalists were traitors. He fought in the Battle of Madrid, but was captured and sentenced to die by firing squad on April 29, 1937.[98]

World War II

Pearl Harbor of the Atlantic

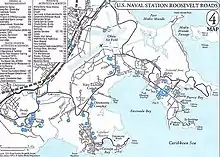

In 1940, when Germany attacked Great Britain, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ordered the construction of a protected anchorage in the Atlantic, at Ceiba, Puerto Rico, similar to Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. The site was meant to provide anchorage, docking, repair facilities, fuel, and supplies for 60% of the Atlantic Fleet. The naval base, which was named U.S. Naval Station Roosevelt Roads, became the largest naval installation in the world in landmass. In May 2003, after six decades of existence, the base was officially shut down by the U.S. Navy.[99][100]

In 1939, a survey was conducted of possible air base sites. It was determined that Punta Borinquen was the best site for a major air base. Later that year, Major Karl S. Axtater assumed command of what was to become Borinquen Army Air Field (later renamed Ramey Air Force Base). The first squadron based at Borinquen Field was the 27th Bombardment Squadron, consisting of nine Douglas B-18A Bolo medium bombers. In 1940, the air echelon of the 25th Bombardment Group (14 B-18A aircraft and two Northrop A-17 aircraft) arrived at the base from Langley Field.[101] Throughout the war, many squadrons rotated through the airbase, which was supported by numerous antiaircraft, coastal artillery and support units. Borinquen Field was also used as a part of the ferrying route for aircraft being moved from Florida to the Middle East.[102][103]

Puerto Ricans in the military

In October 1940, the 295th and 296th Infantry Regiments of the Puerto Rican National Guard, founded by Major General Luis R. Esteves, were called into Federal Active Service and assigned to the Puerto Rican Department in accordance with the existing War Plan Orange.[104]

There were no Puerto Rican military-related fatalities in the Japanese attack of Pearl Harbor, although one Puerto Rican civilian was killed. Daniel LaVerne was an amateur boxer who was working at Pearl Harbor's Red Hill underground fuel tank construction project when the Japanese attacked. He died as a result of the injuries which he received during the attack. His name is listed among the 2,338 Americans killed or mortally wounded on December 7, 1941, in the Remembrance Exhibit on the back lawn of the USS Arizona Memorial Visitor Center at Pearl Harbor.[105]

It is estimated by the Department of Defense that 65,034 Puerto Ricans served in the U.S. military during World War II.[88][106] Soldiers from the island, serving in the 65th Infantry Regiment, participated in combat in the European Theater – in Germany and Central Europe. Those who resided in the mainland of the United States were assigned to regular units of the military and served either in the European or Pacific theaters of the war. Some families had multiple members join the Armed Forces. Seven brothers of the Medina family known as "The Fighting Medinas", fought in the war. They came from Río Grande, Puerto Rico, and Brooklyn, New York.[107] In some cases Puerto Ricans were subject to the racial discrimination which at that time was widespread in the United States.[106]

World War II was also the first conflict in which women, other than nurses, were allowed to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces. However, when the United States entered World War II, Puerto Rican nurses volunteered for service but were not accepted into the Army or Navy Nurse Corps. As a result, many of the volunteers migrated to the mainland U.S. to work in the factories which produced military equipment. In 1944, the Army Nurse Corps decided to actively recruit Puerto Rican nurses so that Army hospitals would not have to deal with the language barriers when tending to wounded Hispanic soldiers. Among them was Second Lieutenant Carmen Lozano Dumler, who became one of the first Puerto Rican female military officers.[108]

In 1944, the Army sought to recruit up to 200 Puerto Rican women for the Women's Army Corps (WAC). Over 1,000 applications were received. The Puerto Rican WAC unit, designated Company 6, 2nd Battalion, 21st Regiment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, was a segregated Hispanic unit. It was assigned to the New York Port of Embarkation after basic training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. The WACs were assigned to work in military offices which planned the shipment of troops around the world.[109] Among them was PFC Carmen García Rosado, who in 2006, authored and published a book titled "LAS WACS – Participacion de la Mujer Boricua en la Segunda Guerra Mundial" (The WACs – The participation of the Puerto Rican women in the Second World War), the first book to document the experiences of the first 200 Puerto Rican women who participated in said conflict.[110] According to García Rosado, one of the hardships which Puerto Rican women in the military were subjected to was social and racial discrimination against the Latino community, which at the time was rampant in the United States.[110]

The 149th Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) Post Headquarters Company was the first WAAC Company to go overseas, setting sail from New York Harbor for Europe in January 1943. The unit arrived in Northern Africa on January 27, 1943, and rendered overseas duties in Algiers within General Dwight D. Eisenhower's theater headquarters. Tech4 Carmen Contreras-Bozak, a member of this unit, was the first Hispanic to serve in the Women's Army Corps as an interpreter and in numerous administrative positions.[111]

The 65th Infantry, after an extensive training program in 1942, was sent to Panama to protect the Pacific and the Atlantic sides of the isthmus in 1943. On November 25, 1943, Colonel Antulio Segarra, proceeded Col. John R. Menclenhall as Commander of the 65th Infantry, thus becoming the first Puerto Rican Regular Army officer to command a Regular Army regiment.[112]

On January 12, 1944, the 296th Infantry Regiment departed from Puerto Rico to the Panama Canal Zone. In April 1945, the unit returned to Puerto Rico and soon after was sent to Honolulu, Hawaii. The 296th arrived on June 25, 1945, and was attached to the Central Pacific Base Command at Kahuku Air Base.[113] Lieutenant Colonel Gilberto José Marxuach, "The Father of the San Juan Civil Defense", was the commander of both the 1114th Artillery Co. and the 1558th Engineers Co.[114]

Also in January 1944, the 65th Infantry Regiment was moved from Panama to Fort Eustis in Newport News, Virginia, in preparation for overseas deployment to North Africa. An advance party was sent to Casablanca on 16 March, with the remainder of the regiment arriving by 5 April.[115] For some Puerto Ricans, this would be the first time that they were away from their homeland. Being away from their homeland for the first time would serve as an inspiration for compositions of two Bolero's; "En mi viejo San Juan" by Noel Estrada[116] and "Despedida" (My Good-bye), a farewell song written by Pedro Flores and interpreted by Daniel Santos.[117] By April 29, 1944, the regiment had landed in Italy and moved on to Corsica. On 1 October 1944, the 65th Infantry landed in France and was committed to action on the Maritime Alps at Peira Cava. On December 13, 1944, the 65th Infantry, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Juan César Cordero Dávila, relieved the 2nd Battalion, 442nd Infantry Regiment, a regiment which was made up of Japanese Americans under the command of Col. Virgil R. Miller, a native of Puerto Rico. The 3rd Battalion fought against and defeated Germany's 34th Infantry Division's 107th Infantry Regiment. There were 17 battle casualties. These included Pvt. Sergio Sanchez-Sanchez and Sergeant Angel Martinez, from the town of Sabana Grande, who were the first two Puerto Ricans from the 65th Infantry to be killed in combat. On March 18, 1945, the regiment was sent to the District of Mannheim and assigned to military occupation duties. In all, the 65th Infantry participated in the campaigns of Naples-Fogis, Rome-Arno, central Europe and of the Rhineland.[118]

It was during this conflict that CWO2 Joseph B. Aviles Sr., a member of the United States Coast Guard and the first Hispanic-American to be promoted to Chief Petty Officer, "received a war-time promotion to Chief Warrant Officer (November 27, 1944), thus becoming the first Hispanic American to reach that level as well."[119] Aviles, who served in the United States Navy as Chief Gunner's Mate in World War I, spent most of the war at St. Augustine, Florida, training recruits.

Commanders

This was also the first time that Puerto Ricans played important roles as commanders in the Armed Forces of the United States. Besides Lieutenant Colonel Juan César Cordero Dávila who served with the 65th Infantry and Colonel Virgil R. Miller, a West Point graduate, born in San Germán, Puerto Rico, who was the regimental commander of the 442d Regimental Combat Team, a unit which was composed of "Nisei" (second generation Americans of Japanese descent), that rescued Lost Texas Battalion of the 36th Infantry Division, in the forests of the Vosges Mountains in northeastern France.[120][121] Colonel Virgilio N. Cordero Jr. (1893–1980) was a battalion commander of the 31st Infantry Regiment on December 8, 1941, when Japanese attacked Philippines.[122] Cordero was named regimental commander of the 52nd Infantry Regiment of the new Filipino Army, thus becoming the first Puerto Rican to command a Filipino Army regiment. The Bataan Defense Force surrendered on April 9, 1942, and Cordero and his men underwent brutal torture and humiliation during the Bataan Death March and nearly four years of captivity. He was one of nearly 1,600 members of the 31st Infantry who were taken as prisoners. Half of these men perished while prisoners of the Japanese forces.[123][124] After Cordero gained his freedom, when the Allied troops defeated the Japanese, he continued serving in the military until 1953.[122]

Seven Puerto Ricans, all graduates of the United States Naval Academy, served in command positions in the Navy and the Marine Corps.[125] Lieutenant General Pedro Augusto del Valle, was the first Hispanic Marine Corps general. He played a key role in the Guadalcanal Campaign and the Battle of Guam and became the Commanding General of the First Marine Division. Del Valle played an instrumental role in the defeat of the Japanese forces in Okinawa and was in charge of the reorganization of Okinawa.[89][126] Admiral Horacio Rivero Jr., USN, who later became the first Puerto Rican to become a four-star admiral; Captain Marion Frederic Ramírez de Arellano, USN, the first Hispanic submarine commanding officer.[127] As submarine commander of the USS Balao (SS-285), he is credited with sinking two Japanese ships; Rear Admiral Rafael Celestino Benítez, USN, a highly decorated submarine commander who was the recipient of two Silver Star Medals; Rear Admiral José M. Cabanillas, USN, who was the executive officer of the USS Texas which participated in the invasions of North Africa and Normandy (D-Day); Rear Admiral Edmund Ernest García, USN, commander of the destroyer USS Sloat who saw action in the invasions of Africa, Sicily, and France; Rear Admiral Frederick Lois Riefkohl, USN, the first Puerto Rican to graduate from the Naval Academy and recipient of the Navy Cross and Colonel Jaime Sabater Sr., USMC, who commanded the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines during the Bougainville amphibious operations. Sabater also participated in the Battle of Guam (July 21 – August 10, 1944) as executive officer of the 9th Marines. He was wounded in action on July 21, 1944, and awarded the Purple Heart.[128]

Notable combatants

Among the many Puerto Ricans who distinguished themselves in combat were Sergeant First Class Agustín Ramos Calero and the first three Puerto Ricans to be awarded the Distinguished Service Cross: PFC. Luis F. Castro, Private Anibal Irrizarry and PFC Joseph R. Martinez.[129][130][131] Sergeant First Class Agustín Ramos Calero was awarded a total of 22 decorations and medals his actions in Europe, making him the most decorated Puerto Rican soldier of World War II.[132]

Aviators

Puerto Ricans also served in the United States Army Air Forces. In 1944, Puerto Rican aviators were sent to the Tuskegee Army Air Field in Tuskegee, Alabama, to train the famed 99th Fighter Squadron of the Tuskegee Airmen. A few Puerto Ricans who served in either the Royal Canadian Air Force, the British Royal Air Force.

Human experimentation

Puerto Rican soldiers were subject to human experimentation by the United States Armed Forces. On Panama's San Jose Island, Puerto Rican soldiers were exposed to mustard gas to see if they reacted differently than their "white" counterparts.[133] According to Susan L. Smith of the University of Alberta, the researchers were searching for evidence of race-based differences in the responses of the human body to mustard gas exposure.[134]

Demobilization

The American participation in the Second World War came to an end in Europe on May 8, 1945, when the western Allies celebrated "V-E Day" (Victory in Europe Day) upon Germany's surrender, and in the Asian theater on August 14, 1945 "V-J Day" (Victory over Japan Day) when the Japanese surrendered by signing the Japanese Instrument of Surrender. Lieutenant Junior Grade Maria Rodriguez Denton (U.S. Navy), born in Guanica, Puerto Rico, was the first woman from Puerto Rico who became an officer in the United States Navy as member of the WAVES. It was LTJG Denton who forwarded the news (through channels) to President Harry S. Truman that the war had ended.[108]

On October 27, 1945, the 65th Infantry sailed home from France. Arriving at Puerto Rico on November 9, 1945, they were received by the local population as national heroes and given a victorious reception at the Military Terminal of Camp Buchanan.[135]

According to the book "Historia Militar De Puerto Rico" (Military history of Puerto Rico), by historian Col. Héctor Andrés Negroni, the men of the 65th Infantry were awarded the following military decorations: 2 Silver Stars, 22 Bronze Stars, and 90 Purple Hearts.[37]

The 295th Regiment returned on February 20, 1946, from the Panama Canal Zone, and the 296th Regiment on March 6. Both regiments were awarded the American Theater streamer and the Pacific Theater streamer. They were inactivated that same year.[136]

According to the 4th Report of the Director of Selective Service of 1948, a total of 51,438 Puerto Ricans served in the Armed Forces during World War II, however, the Department of Defense in its report titled "Number of Puerto Ricans serving in the U.S. Armed Forces during National Emergencies" stated that the total of Puerto Ricans who served was 65,034 and from that total 2,560 were listed as wounded.[88] Unfortunately, the exact total amount of Puerto Ricans who served in World War II in other units, besides those of Puerto Rico, cannot be determined because the military categorized Hispanics under the same heading as whites. The only racial groups to have separate statistics kept were African-Americans and Asian Americans.[137][138]

Revolt against the United States

During the mid-1940s, various pro-independence groups, such as the Puerto Rican Independence Party, which believed in gaining the island's independence through the electoral process, and the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party, which believed in the concept of armed revolution, existed in Puerto Rico. On October 30, 1950, the nationalists, under the leadership of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos staged uprisings in the towns of Ponce, Mayagüez, Naranjito, Arecibo, Utuado (Utuado Uprising), San Juan (San Juan Nationalist revolt) and Jayuya.

The most notable of these occurred in Jayuya in what became known as El Grito de Jayuya (Jayuya Uprising). Nationalist leader Blanca Canales led the armed nationalists into the town and attacked the police station. A small battle with the police occurred; one officer was killed and three others were wounded before the rest dropped their weapons and surrendered. The nationalists cut the telephone lines and burned the post office. Canales led the group into the town square where the illegal light blue version of the Puerto Rican Flag was raised (it was against the law to carry a Puerto Rican Flag from 1898 to 1952.) In the town square, Canales gave a speech and declared Puerto Rico a free Republic. The town was held by the nationalists for three days.[139]

The United States declared martial law in Puerto Rico and sent the Puerto Rico National Guard to attack Jayuya. The town was attacked by U.S. bomber planes and ground artillery. Even though part of the town was destroyed, news of this military action was prevented from spreading outside of Puerto Rico. It was called an incident between Puerto Ricans. The top leaders of the nationalist party, including Albizu Campos and Blanca Canales, were arrested and sent to jail to serve long prison terms.[139]

Griselio Torresola, Albizu Campos's bodyguard, was in the United States at the time of the Jayuya Uprising. Torresola and fellow nationalist Oscar Collazo, were to assassinate President Harry S. Truman. On November 1, 1950, they attacked the Blair House where Torresola and a policeman, Leslie Coffelt, lost their lives. Oscar Collazo was arrested and sentenced to death. His sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment by President Truman, and he eventually received a presidential pardon.[139]

Cold War (1947–1991)

After World War II a geopolitical, ideological, and economic struggle emerged between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies. Popularly named the Cold War, open hostilities never occurred between the main parties involved. Instead it involved a nuclear and conventional weapons arms race, networks of military alliances, economic warfare and trade embargoes, propaganda, espionage, and smaller conflicts. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 was the most important direct confrontation. The Korean and Vietnam War were among the major civil wars polarized along Cold War lines.[140][141]

Puerto Rico Air National Guard

Colonel Mihiel Gilormini was named commander of the 198th Fighter Squadron in Puerto Rico. Gilormini and Colonel Alberto A. Nido, together with Lieutenant Colonel Jose Antonio Muñiz, played an instrumental role in the creation of the Puerto Rico Air National Guard on November 23, 1947. The Puerto Rico Air National Guard is a part of the Air Reserve Component (ARC) of the United States Air Force.[142] Both Gilormini and Nido were eventually promoted to brigadier general and served as commanders of PRANG. In 1963, the Air National Guard Base, at the San Juan International airport in Puerto Rico, was renamed "Muñiz Air National Guard Base" in honor of Lt. Col. Jose Antonio Muñiz who died on July 4, 1960, when his F-86 crashed during takeoff during the 4th of July festivities in Puerto Rico.[143]

USS Cochino incident

The USS Cochino (SS-345) was a Gato-class submarine under the command of Commander Rafael Celestino Benítez. On August 12, 1949, the Cochino, along with the USS Tusk (SS-426), departed from Portsmouth, United Kingdom. Both diesel submarines were supposed to be on a cold-water training mission, however, according to Blind Man's Bluff: The Untold Story of American Submarine Espionage,[144] the submarines were part of an American intelligence operation. They had snorkels that allowed them to spend long periods underwater, largely invisible to an enemy, and they carried electronic gear designed to detect far-off radio signals. The mission of the Cochino and the Tusk was to eavesdrop on communications that revealed the testing of submarine-launched Soviet missiles that might soon carry nuclear warheads; it was the first American undersea spy mission of the Cold War.

The mission was cut short when one of the Cochino's 4,000-pound batteries caught fire. Benitez directed the firefighting, trying both to save the ship and his crew from the toxic gases. The crew members of the Tusk rescued all except one Cochino crew member and convinced Benitez, who was the last man on the Cochino, to board the Tusk. The Cochino sank off the coast of Norway two minutes after Benitez's departure. Benitez retired from the Navy in 1957 as a rear admiral.[145]

Korean War

Sixty-one thousand Puerto Ricans served in the Korean War, including 18,000 Puerto Ricans who enlisted in the continental United States.[89] On August 26, 1950, the 65th Infantry Regiment departed from Puerto Rico and arrived in Pusan, Korea on September 23, 1950. It was during the long sea voyage that the 65th Infantry was nicknamed the "Borinqueneers". The name is a combination of the words "Borinquen" (the Taíno name for Puerto Rico) and "Buccaneers". Among the hardships suffered by the Puerto Ricans after they arrived in Korea was the lack of warm clothing during the cold, harsh winters. The enemy made many attempts to encircle the regiment, but each time they failed because of the many casualties inflicted by the 65th. In December 1950, U.S. Marines found themselves at the Chosin Reservoir area. The 65th was part of a task force which enabled the Marines to withdraw from Hangu-Ri.

In December 1952, 162 Puerto Ricans of the 65th Infantry were arrested, 95 were court-martialed, and 91 were found guilty and sentenced to prison terms ranging from 1 to 18 years of hard labor. It was the largest mass court martial of the Korean War. The Secretary of the Army Robert T. Stevens moved quickly to remit the sentences and granted clemency and pardons to all those involved. Though the men who were court-martialed were pardoned in 1954, a campaign was later started to obtain a formal exoneration.[146]

Among the battles and operations in which the 65th participated was the Operation "Killer" of January 1951, becoming the first regiment to cross the Han River. In April 1951, the regiment participated in the Uijonber Corridor drives and in June 1951, the 65th was the third regiment to cross the Han Ton River. Master Sergeant Juan E. Negrón received the Medal of Honor posthumously on March 18, 2014, for his courageous actions while serving as a member of Company L, 65th Infantry Regiment, 3d Infantry Division during combat operations against an armed enemy in Kalma-Eri, Korea on April 28, 1951.[147]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

The 65th helped push the advance from Ch'orwon towards P'yonggang in June and then assisted in breaking the Iron Triangle of Hill 717 in July 1951.[148] In late November 1951, the 65th successfully fought off an attack by two battalion-sized enemy units. Colonel Juan César Cordero Dávila was named commander of 65th Infantry on February 1, 1952, thus becoming one of the highest-ranking ethnic officers in the Army.[149] Commencing on July 3, 1952, the regiment defended the main line of resistance (MLR) for 47 days and saw action at Cognac, King and Queen with successful attacks on Chinese positions. In September 1952, the 65th Infantry was holding on to a hill known as Outpost Kelly. Chinese Communist forces that had joined the North Koreans overran the hill in what became known as the Battle of Outpost Kelly. The 65th Infantry Regiment launched several efforts to retake the position but was overwhelmed by Chinese artillery and driven off on 24 September.[150] In October the regiment also saw action in the Cherwon Sector and on Iron Horse, around Hill 391, which became known as Jackson Heights.[151]

In June 1953, the 2nd Battalion, 65th Infantry Regiment conducted a series of successful raids on Hill 412 in support of a position called Outpost Harry,[152] and later the regiment conducted several successful raids in addition to defending defensive positions near the base of the Iron Triangle until the armistice was signed in July.[153]

The 65th Infantry was credited with battle participation in nine campaigns.[note 1] Among the distinctions awarded to the members of the 65th were a Medal of Honor,[note 2] 10 Distinguished Service Crosses, 256 Silver Stars and 595 Bronze Stars. According to El Nuevo Día newspaper, May 30, 2004, a total of 756 Puerto Ricans lost their lives in Korea and a total of 3,630 men were wounded, from all four branches of the U.S. Armed Forces. More than half of these were from the 65th Infantry (not including non-Puerto Ricans). The 65th Infantry returned to Puerto Rico and was deactivated in 1956. However, Major General Juan César Cordero Dávila, Puerto Rico's Adjutant General (1958–65), persuaded the Department of the Army to transfer the 65th Infantry from the regular Army to the Puerto Rican National Guard. This was the only unit ever transferred from active component Army to the Army Guard.[146]

Mass court-martial