| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Mycostatin, Nystop, others[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682758 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | topical, vaginal, by mouth (but not absorbed) |

| Drug class | Polyene antifungal medication[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 0% on oral ingestion |

| Metabolism | None (not extensively absorbed) |

| Elimination half-life | Dependent upon GI transit time |

| Excretion | Fecal (100%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.014.317 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

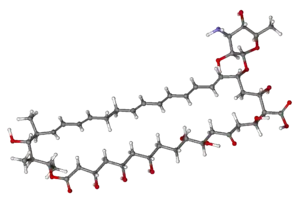

| Formula | C47H75NO17 |

| Molar mass | 926.107 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 44–46 °C (111–115 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Nystatin, sold under the brandname Mycostatin among others, is an antifungal medication.[1] It is used to treat Candida infections of the skin including diaper rash, thrush, esophageal candidiasis, and vaginal yeast infections.[1] It may also be used to prevent candidiasis in those who are at high risk.[1] Nystatin may be used by mouth, in the vagina, or applied to the skin.[1]

Common side effects when applied to the skin include burning, itching, and a rash.[1] Common side effects when taken by mouth include vomiting and diarrhea.[1] During pregnancy use in the vagina is safe while other formulations have not been studied in this group.[1] It works by disrupting the cell membrane of the fungal cells.[1]

Nystatin was discovered in 1950 by Rachel Fuller Brown and Elizabeth Lee Hazen.[2] It was the first polyene macrolide antifungal.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4] It is available as a generic medication.[1] It is made from the bacterium Streptomyces noursei.[2] In 2020, it was the 227th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[5][6]

Medical uses

Skin, vaginal, mouth, and esophageal Candida infections usually respond well to treatment with nystatin. Infections of nails or hyperkeratinized skin do not respond well.[7] It is available in many forms.

When given parenterally, its activity is reduced due to presence of plasma.[8]

Oral nystatin is often used as a preventive treatment in people who are at risk for fungal infections, such as AIDS patients with a low CD4+ count and people receiving chemotherapy. It has been investigated for use in patients after liver transplantation, but fluconazole was found to be much more effective for preventing colonization, invasive infection, and death.[9] It is effective in treating oral candidiasis in elderly people who wear dentures.[10]

It is also used in very low birth-weight (less than 1500 g or 3 lb 5oz o) infants to prevent invasive fungal infections, although fluconazole is the preferred treatment. It has been found to reduce the rate of invasive fungal infections and also reduce deaths when used in these babies.[11]

Liposomal nystatin is not commercially available, but investigational use has shown greater in vitro activity than colloidal formulations of amphotericin B, and demonstrated effectiveness against some amphotericin B-resistant forms of fungi.[12] It offers an intriguing possibility for difficult-to-treat systemic infections, such as invasive aspergillosis, or infections that demonstrate resistance to amphotericin B. Cryptococcus is also sensitive to nystatin. Additionally, liposomal nystatin appears to cause fewer cases of and less severe nephrotoxicity than observed with amphotericin B.[12]

In the UK, its license for treating neonatal oral thrush is restricted to those over the age of one month.

It is prescribed in 'units', with doses varying from 100,000 units (for oral infections) to 1 million (for intestinal ones). As it is not absorbed from the gut, it is fairly safe for oral use and does not have problems of drug interactions. On occasion, serum levels of the drug can be identified from oral, vaginal, or cutaneous administration, and lead to toxicity.

Adverse effects

Bitter taste and nausea are more common than most other adverse effects.[7]

The oral suspension form produces a number of adverse effects including but not limited to:[13]

- Diarrhea

- Abdominal pain

- Rarely, tachycardia, bronchospasm, facial swelling, muscle aches

Both the oral suspension and the topical form can cause:

- Hypersensitivity reactions, including Stevens–Johnson syndrome in some cases[14]

- Rash, itching, burning and acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis[15]

Too high of a dosage can potentially lead to additional side effects such as:[16]

- Nephrotoxicity

- Hypokalemia

- Chills and skin rash

Mechanism of action

Like amphotericin B and natamycin, nystatin is an ionophore.[17] It binds to ergosterol, a major component of the fungal cell membrane. When present in sufficient concentrations, it forms pores in the membrane that lead to K+ leakage, acidification, and death of the fungus.[18] Ergosterol is a sterol unique to fungi, so the drug does not have such catastrophic effects on animals or plants. However, many of the systemic/toxic effects of nystatin in humans are attributable to its binding to mammalian sterols, namely cholesterol. This is the effect that accounts for the nephrotoxicity observed when high serum levels of nystatin are achieved.[16] Despite the molecular similarities and differences of ergosterol and cholesterol, there is currently no consensus as to why nystatin has a higher binding affinity for ergosterol because we don't understand how the nystatin pores are constructed.[19] Researchers have concluded thus far that nystatin pores are formed from 4-12 nystatin molecules, with an unknown number of the necessary sterol interactions.[20]

Nystatin also impacts cell membrane potential and transport by lipid peroxidation.[21] Conjugated double bonds in nystatin's structure steal electron density from ergosterol in fungal cell membranes. Lipid peroxidation alters the hydrophilicity of the interior of channels in the membrane, which is necessary to transport ions and polar molecules. Disruption of membrane transport from nystatin results in rapid cell death. Lipid peroxidation by nystatin also contributes significantly to K+ leakage due to structural modifications of the membrane.[22]

Biosynthesis

Nystatin A1 (or referred to as nystatin) is biosynthesized by a bacterial strain, Streptomyces noursei.[23] The structure of this active compound is characterized as a polyene macrolide with a deoxysugar D-mycosamine, an aminoglycoside.[23] The genomic sequence of nystatin reveals the presence of the polyketide loading module (nysA), six polyketide syntheses modules (nysB, nysC, nysI, nysJ, and nysK) and two thioesterase modules (nysK and nysE).[23] It is evident that the biosynthesis of the macrolide functionality follows the polyketide synthase I pathway.[24]

Following the biosynthesis of the macrolide, the compound undergoes post-synthetic modifications, which are aided by the following enzymes: GDP-mannose dehydratase (nysIII), P450 monooxygenase (nysL and nysN), aminotransferase (nysDII), and glycosyltransferase (nysDI).[23] The biosynthetic pathway is thought to proceed as shown to yield nystatin.

Loading to 5

Loading to 5 Modules 6-12

Modules 6-12 Modules 13 -18

Modules 13 -18 Completed molecule

Completed molecule

The melting point of nystatin is 44 - 46 °C.[25]

History

Like many other antifungals and antibiotics, nystatin has bacterial origin. It was isolated from Streptomyces noursei in 1950 by Elizabeth Lee Hazen and Rachel Fuller Brown, who were doing research for the Division of Laboratories and Research of the New York State Department of Health. Hazen found a promising micro-organism in the soil of a friend's dairy farm. She named it Streptomyces noursei, after Jessie Nourse, the wife of the farm's owner.[26] Hazen and Brown named nystatin after the New York State Health Department in 1954.[27] The two discoverers patented the drug, and then donated the $13 million in profits to a foundation to fund similar research.[28]

Other uses

It is also used in cellular biology as an inhibitor of the lipid raft-caveolae endocytosis pathway on mammalian cells, at concentrations around 3 μg/ml.

In certain cases, a nystatin derivative has been used to prevent the spread of mold on objects such as works of art. For example, it was applied to wood panel paintings damaged as a result of the Arno River Flood of 1966 in Florence, Italy.[29]

Nystatin is also used as a tool by scientists performing "perforated" patch-clamp electrophysiological recordings of cells. When loaded in the recording pipette, it allows for measurement of electrical currents without washing out the intracellular contents, because it forms pores in the cell membrane that are permeable to only monovalent ions,[30] preferably cations such as sodium, potassium, lithium, and cesium.[31]

Another electrophysiological measurement that can be made is fusion event duration in a nystatin-ergosterol based system. Fusions are measured while the voltage is held constant, and is characterized by a spike in the current that then returns to the baseline current as the nystatin channels close. When present in smaller concentrations, nystatin momentarily forms pores that allows a vesicle fusion to occur more easily; that fusion then interrupts the pore stability and the nystatin and ergosterol disperse from each other.[32] Conversely, researchers have found that the half-life of these nystatin pores increase with an increased dosage level of nystatin to the membrane systems. This indicates a lower energy of both the lipid membrane and the ionophores when there is a higher concentration of nystatin.[33]

Formulations

- An oral suspension form is used for the prophylaxis or treatment of oropharyngeal thrush, a superficial candidal infection of the mouth and pharynx.

- A tablet form is preferred for candidal infections in the intestines.

- Nystatin is available as a topical cream and can be used for superficial candidal infections of the skin.

- Additionally, a liposomal formulation of nystatin was investigated in the 1980s and into the early 21st century. The liposomal form was intended to resolve problems arising from the poor solubility of the parent molecule and the associated systemic toxicity of the free drug.

- Nystatin pastilles have been shown to be more effective in treating oral candidiasis than nystatin suspensions.[10]

Due to its toxicity profile when high levels in the serum are obtained, no injectable formulations of this drug are currently on the US market. However, injectable formulations have been investigated in the past.[12]

Brand names

The original brandname was Fungicidin

- Nyamyc

- Pedi-Dri

- Pediaderm AF Complete

- Candistatin

- Nyaderm

- Bio-Statin

- PMS-Nystatin

- Nystan (oral tablets, topical ointment, and pessaries, formerly from Bristol-Myers Squibb)

- Infestat

- Nystalocal from Medinova AG

- Nystamont

- Nystop (topical powder, Paddock)

- Nystex

- Mykinac

- Nysert (vaginal suppositories, Procter & Gamble)

- Nystaform (topical cream, and ointment and cream combined with iodochlorhydroxyquine and hydrocortisone; formerly Bayer now Typharm Ltd)

- Nilstat (vaginal tablet, oral drops, Lederle)

- Korostatin (vaginal tablets, Holland Rantos)

- Mycostatin (vaginal tablets, topical powder, suspension Bristol-Myers Squibb)

- Mycolog-II (topical ointment, combined with triamcinolone; Apothecon)

- Mytrex (topical ointment, combined with triamcinolone)

- Mykacet (topical ointment, combined with triamcinolone)

- Myco-Triacet II (topical ointment, combined with triamcinolone)

- Flagystatin II (cream, combined with metronidazole)

- Timodine (cream, combined with hydrocortisone and dimethicone)

- Nistatina (oral tablets, Antibiotice Iaşi)

- Nidoflor (cream, combined with neomycin sulfate and triamcinolone acetonide)

- Stamicin (oral tablets, Antibiotice Iaşi)

- Lystin

- Animax (veterinary topical ointment or cream; combined with neomycin sulfate, thiostrepton and triamcinolone acetonide)

- Nyata (topical powder)[34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Nystatin". American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 2016-02-03. Retrieved 2016-01-27.

- 1 2 Espinel-Ingroff AV (2013). Medical Mycology in the United States a Historical Analysis (1894-1996). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. p. 62. ISBN 9789401703116. Archived from the original on 2016-02-02.

- ↑ Gupte M, Kulkarni P, Ganguli BN (January 2002). "Antifungal antibiotics". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 58 (1): 46–57. doi:10.1007/s002530100822. PMID 11831475. S2CID 8015426.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06.

- ↑ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ "Nystatin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- 1 2 Hilal-Dandan R, Knollmann B, Brunton L (2017-12-05). Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, Hilal-Dandan R (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's the Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (Thirteenth ed.). New York. ISBN 9781259584732. OCLC 994570810.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Satoskar RS, Rege N, Bhandarkar SD (2015). Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics. Chennai: Elsevier. ISBN 978-8131243619. OCLC 978526697.

- ↑ Gøtzsche PC, Johansen HK (September 2014). "Nystatin prophylaxis and treatment in severely immunodepressed patients". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (9): CD002033. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002033.pub2. PMC 6457783. PMID 25188770.

- 1 2 Lyu X, Zhao C, Yan ZM, Hua H (2016). "Efficacy of nystatin for the treatment of oral candidiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Drug Design, Development and Therapy. 10: 1161–1171. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S100795. PMC 4801147. PMID 27042008.

- ↑ Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, et al. (March 2009). "Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 48 (5): 503–535. doi:10.1086/596757. PMC 7294538. PMID 19191635.

- 1 2 3 Hamill RJ (2003). "Liposomal Nystatin". In Dismukes WE, Pappas PG, Sobel JD (eds.). Clinical Mycology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN 978-0-19-514809-1.

- ↑ "Nystatin (Oral route)". Micromedex Detailed Drug Information. PubMed Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved Apr 1, 2014.

- ↑ "FDA approved package insert" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-04-21.

- ↑ Rosenberger A, Tebbe B, Treudler R, Orfanos CE (June 1998). "[Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, induced by nystatin]". Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift Fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und Verwandte Gebiete (in German). 49 (6): 492–495. doi:10.1007/s001050050776. PMID 9675578. S2CID 10935411.

- 1 2 Groll AH, Piscitelli SC, Walsh TJ (1998-01-01), August JT, Anders MW, Murad F, Coyle JT (eds.), Clinical Pharmacology of Systemic Antifungal Agents: A Comprehensive Review of Agents in Clinical Use, Current Investigational Compounds, and Putative Targets for Antifungal Drug Development, Advances in Pharmacology, vol. 44, Academic Press, pp. 343–500, doi:10.1016/S1054-3589(08)60129-5, ISBN 9780120329458, PMID 9547888, retrieved 2023-12-09

- ↑ Rang HP, Dale MM, Flower RJ, Henderson G (2015-01-21). Rang and Dale's pharmacology (Eighth ed.). [United Kingdom]. ISBN 9780702053627. OCLC 903083639.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Hammond SM (1977). Biological activity of polyene antibiotics. Progress in Medicinal Chemistry. Vol. 14. pp. 105–79. doi:10.1016/S0079-6468(08)70148-6. ISBN 9780720406450. PMID 345355.

- ↑ Groll AH, Piscitelli SC, Walsh TJ (1998), "Clinical Pharmacology of Systemic Antifungal Agents: A Comprehensive Review of Agents in Clinical Use, Current Investigational Compounds, and Putative Targets for Antifungal Drug Development", Advances in Pharmacology, Elsevier, vol. 44, pp. 343–500, doi:10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60129-5, ISBN 978-0-12-032945-8, PMID 9547888, retrieved 2023-12-09

- ↑ Helrich CS, Schmucker JA, Woodbury DJ (August 2006). "Evidence that Nystatin Channels Form at the Boundaries, Not the Interiors of Lipid Domains". Biophysical Journal. 91 (3): 1116–1127. Bibcode:2006BpJ....91.1116H. doi:10.1529/biophysj.105.076281. ISSN 0006-3495. PMC 1563755. PMID 16679364.

- ↑ Welman E, Peters TJ (June 1976). "Properties of lysosomes in guinea pig heart: subcellular distribution and in vitro stability". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 8 (6): 443–463. Bibcode:1993BpJ....64...92B. doi:10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81343-2. PMC 1262305. PMID 7679.

- ↑ Stark G (July 1991). "The effect of ionizing radiation on lipid membranes". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Biomembranes. 1071 (2): 103–122. doi:10.1016/0304-4157(91)90020-w. PMID 1854791.

- 1 2 3 4 Fjaervik E, Zotchev SB (June 2005). "Biosynthesis of the polyene macrolide antibiotic nystatin in Streptomyces noursei". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 67 (4): 436–443. doi:10.1007/s00253-004-1802-4. PMID 15700127. S2CID 19291518.

- ↑ Dewick PM (2009). Medicinal Natural Products: A Biosynthetic Approach (3rd ed.). UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. ISBN 978-0-471-97478-9.

- ↑ Elsner Z, Leszczyńska-Bakal H, Pawlak E, Smazyński T (1976). "Gel with nystatin for treatment of lung mycosis". Polish Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacy. 28 (4): 349–352. PMID 981024.

- ↑ Espinel-Ingroff A (2003). Medical mycology in the United States: a historical analysis (1894-1996). Springer. p. 62.

- ↑ Kelly K (2010). Medicine Becomes a Science: 1840-1999. Infobase. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-4381-2752-1. Archived from the original on 2017-03-23.

- ↑ Sicherman B, Green CH (1980). Notable American Women: The Modern Period : a Biographical Dictionary. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-674-62733-8. Archived from the original on 2017-03-23.

- ↑ Brommelle NS (1970). "The Restoration of Damaged Art Treasures in Florence and Venice". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. 118 (5165): 260–269. ISSN 0035-9114. JSTOR 41370578.

- ↑ Akaike N, Harata N (1994). "Nystatin perforated patch recording and its applications to analyses of intracellular mechanisms". The Japanese Journal of Physiology. 44 (5): 433–473. doi:10.2170/jjphysiol.44.433. PMID 7534361.

- ↑ Korn SJ, Marty A, Connor JA, Horn R (1991-01-01), Conn PM (ed.), "[22] - Perforated Patch Recording", Methods in Neurosciences, Electrophysiology and Microinjection, Academic Press, vol. 4, pp. 364–373, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-185257-3.50027-6, ISBN 9780121852573, retrieved 2023-12-09

- ↑ Rognlien KT, Woodbury DJ (2003-01-01), Tien HT, Ottova-Leitmannova A (eds.), "Chapter 16 - Reconstituting SNARE proteins into BLMs", Membrane Science and Technology, Planar Lipid Bilayers (BLMs) and Their Applications, Elsevier, vol. 7, pp. 479–488, doi:10.1016/S0927-5193(03)80040-2, ISBN 9780444509406, retrieved 2023-12-09

- ↑ Coutinho A, Prieto M (May 2003). "Cooperative Partition Model of Nystatin Interaction with Phospholipid Vesicles". Biophysical Journal. 84 (5): 3061–3078. Bibcode:2003BpJ....84.3061C. doi:10.1016/s0006-3495(03)70032-0. ISSN 0006-3495. PMC 1302868. PMID 12719237.

- ↑ "Nyata 100,000 Unit/Gram Topical Powder - Uses, Side Effects, and More". WebMD LLC. Retrieved 2018-11-11.

External links

- "Nystatin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.