| Old Parliament House | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Front (northeastern) elevation | |

| Former names | Provisional Parliament House |

| Alternative names | Parliament House |

| General information | |

| Type | Parliament House |

| Architectural style | Stripped Classical |

| Address | 18 King George Terrace, Parkes, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory |

| Country | Australia |

| Coordinates | 35°18′08″S 149°07′47″E / 35.30222°S 149.12972°E |

| Current tenants | Museum of Australian Democracy |

| Construction started | 28 August 1923 |

| Opened | 9 May 1927 |

| Renovated | 1992 |

| Cost | A£600,000 |

| Owner | Australian Government |

| Height | 18.5 metres (61 feet) (without flagpole) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Brick |

| Floor count | 3 |

| Grounds | 2.5 hectares (6 acres) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | John Smith Murdoch |

| Renovating team | |

| Awards and prizes | Engineering Heritage Recognition Program |

| Website | |

| moadoph.gov.au | |

| Official name | Old Parliament House and Curtilage, King George Tce, Parkes, ACT, Australia |

| Type | Listed place |

| Criteria | A., B., D., E., F., G., and H. |

| Designated | 22 June 2004 |

| Reference no. | 105318 |

| References | |

| [1] | |

Old Parliament House, formerly known as the Provisional Parliament House, was the seat of the Parliament of Australia from 1927 to 1988. The building began operation on 9 May 1927 after Parliament's relocation from Melbourne to the new capital, Canberra. In 1988, the Commonwealth Parliament transferred to the new Parliament House on Capital Hill. It also serves as a venue for temporary exhibitions, lectures and concerts. Old Parliament House is, looking across Lake Burley Griffin, situated in front of Parliament House and in line with the Australian War Memorial.

On 2 May 2008, it was made an Executive Agency of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.[2] On 9 May 2009, the Executive Agency was renamed as the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House (MoAD), reporting to the Special Minister of State.

Designed by John Smith Murdoch and a team of assistants from the Department of Works and Railways, the building was intended to be neither temporary nor permanent—only to be a "provisional" building that would serve the needs of Parliament for a maximum of 50 years. The design extended from the building itself to include its gardens, décor and furnishings. The building is in the Simplified or "Stripped" Classical Style, commonly used for Australian government buildings constructed in Canberra during the 1920s and 1930s. It does not include such classical architectural elements as columns, entablatures or pediments, but does have the orderliness and symmetry associated with neoclassical architecture.

Façade and design elements

Old Parliament House is a three-storey brick building with the principal floor on the middle level. Murdoch designed it to be simple and functional, and this is reflected throughout the design, extending to the interior fittings and furnishings.

The facade originally incorporated a grid of recessed openings and balconies, with four bays having arched bronze windows and stepped parapets. The building's front façade has strong horizontal lines, displaying only two storeys, with higher massed elements behind the façade on either side of the centre, indicating the location of the two debating chambers, with a lower mass in the centre where King's Hall is located. Murdoch's simplified classical design is based on a basic square, which provides the building with a regular proportion in terms of fenestration and other elements, including the (now enclosed) verandas and colonnades. The height of the building at the roof of the chambers is 18.5 metres (61 ft) (excluding the flagpole).

The building was constructed from Canberra clay brick, with timber and lightweight concrete floors. It was rendered originally in white concrete, since painted, except for a pedestal of bricks left with their natural colour. The original roofs were constructed of flat concrete slabs with a membrane waterproofing and finished with a bituminous coating which was designed to be walked on. At the roofline, on either side of the main entrance, are large painted reliefs of the Royal and Commonwealth coats of arms. The railings on the front steps were installed after the federal parliament had left the building and were not present during its active lifetime.

The interior continues the stripped-classicism of the exterior, with the use of common motifs and simple lines, in both the decor and furnishings. To represent the federal nature of the Commonwealth of Australia, the building also makes extensive use of timbers from various parts of Australia, with a timber native to each state, (except South Australia), being used for different purposes. The building is also designed to make good use of natural light from windows, skylights and light-wells.

Maintenance and restoration activities are being performed as detailed in a Heritage Management Plan.[3]

Plan

In keeping with its classicised forms, the building has strong symmetrical planning based on a number of major spaces. The major axis through the building, which is part of the land axis of Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin's design, is through King's Hall, the Parliamentary Library and the dining rooms at the back. The cross-axis features the House of Representatives and Senate chambers on either side of King's Hall.

Originally having an H-shape, the building now forms a large rectangle as a consequence of various extensions, with a small rear projection. The building now contains four courtyards and some light-wells. The courtyards are surrounded by colonnades at ground level and (now enclosed) verandas on the main floor.

At the centre is King's Hall. It is named for King George V, whose statue is in the room. Directly adjacent to King's Hall are the chambers of the House of Representatives (to the south-east) and the Senate (to the north-west). To the rear is the Parliamentary Library (occupied from 1998 to 2008 by the National Portrait Gallery) and behind it the dining rooms.

The rest of the main floor of the building was given to offices and meeting rooms. On either side of each of the parliamentary chambers are meeting rooms for the government and opposition parties and—at the end of each block—what were intended originally to be suites for the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President of the Senate. At the rear of the building were dining rooms for members and senators and for 'strangers'. On the basement level were service areas and some offices; on the top floor were more offices and the facilities of the parliamentary press gallery.

King's Hall

From the entrance, a flight of stairs leads up to King's Hall. King's Hall is a large square room, with an ambulatory around the outer edges. It is entered from the main central entrance and up a flight of stairs. The central space has a coffered ceiling and is lit from above by clerestory windows on all four sides. The floor is parquetry, made of jarrah and silver ash woods. Dominating the room is a larger than life bronze statue of King George V, monarch at the time the building was completed, but who, as Duke of York, also represented his father King Edward VII at the opening of the first Commonwealth Parliament on 9 May 1901 in Melbourne.

On eight of the columns surrounding the room are bronze reliefs of persons prominent in the formation of the Commonwealth. In the ambulatory are portraits of Australian Governors-General, Prime Ministers, Speakers of the House of Representatives and presidents of the Senate, and pictures of events associated with the building, such as the opening ceremony of 1927.

Chambers

The chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives are large internal spaces, with ceilings considerably higher than that of King's Hall. Both chambers are the same size, despite the requirement of section 24 of the Australian Constitution that the House of Representatives should have, as nearly as practicable, twice the number of members as the Senate. Both are lined with timber panelling, again representative of Murdoch's simplified classical style, with furnishings in a similar style. The timber used in the wall panelling, the desks, seats and tables is all Australian black bean wood and Tasmanian blackwood. The hand-woven carpets in each chamber have a pattern of eucalyptus leaves and wattle blossom.

The Senate is characterised by the predominance of the colour red, in both the carpet and the red leather of the seating and desks. This reflects its role as the upper house and as a deliberative house like the House of Lords at Westminster. The seating is in a horse-shoe pattern, around a central table. Each senator had a seat and a desk, including those sitting on the front benches (i.e., ministers). At the end of the table is a desk for the clerks and behind them a large chair for the president. Behind it are two thrones, to be used by the monarch and consort or, in their stead, the Governor-General and spouse, at official occasions such as the State Opening of Parliament. The furnishings conform to Murdoch's simplified classical style.

The walls of the Senate chamber are lined with blackbean timber (which is also used for the furnishings) and above this are located galleries on each side. The gallery above the throne was reserved for the press, with others used by the guests of senators, members of the House of Representatives and the general public.

The House of Representatives largely corresponds, in terms of design elements, to the Senate. However, the chamber is characterised by the colour green, representing the historic inheritance of the Representatives, as the lower house and the house in which governments are formed, from the House of Commons in the Palace of Westminster.

There are three basic differences between the House of Representatives chamber and that of the Senate. Firstly, the House is more crowded with seating than the Senate, reflecting the requirement for double the number of members. Secondly, the front benches are long, continuous benches with no desks, similar to the front benches of the House of Commons. Thirdly, the Speaker's Chair presents a significant stylistic contrast, as it is a copy of A.W.N. Pugin's Speaker's Chair in the British House of Commons, presented to the Australian Parliament by the British branch of the Empire Parliamentary Association in 1926. This chair was then copied for the replacement of the original Speaker's Chair in the House of Commons, destroyed in an air raid during the Second World War, which was a gift of the Australian Parliament to the House of Commons. The Royal coat of arms over the chair is carved in oak from timber originally built into Westminster Hall in 1399. The hinged flaps of the armrests are of oak from Nelson's flagship HMS Victory, in the Battle of Trafalgar (1805). The chair symbolises the Australian Parliament's associations with British history and the Parliament at Westminster.

Interiors

The Murdoch-designed interiors remain in substantial areas of the building, sometimes with their original furnishings. The three best-preserved interiors, other than King's Hall and the Chambers, are the Government party room (on the House of Representatives side), the Senate club room (also called the Senate Opposition party room) and the Clerk of the Senate's office (which was originally the President of the Senate's office). All retain their original fittings and furnishings, designed by Murdoch and his team in accordance with the simplified classical design scheme. These are characterised by simple forms, based on Murdoch's square motif.

The original building was small and did not provide individual offices for all members. To an extent, this was to be mitigated by ministers having offices in their own departments, originally in the east and west blocks (also designed by Murdoch). For this reason, the party rooms are not just meeting rooms but contain private phone booths, washbasins, desks and small areas for more intimate discussions.

Gardens

Originally, the rear courtyards of the building were open to the gardens through a colonnade, Murdoch's intention being that members and Senators should be able to use the gardens as an integral part of the building. Later this intention was lost, as extensions were added to the back part of the building to provide more offices.

Murdoch also envisaged the adjacent gardens as a continuation of the House’s courtyards. These parliamentary gardens are situated on either side of the building, they are enclosed by hedges and contain minimal trees. In both cases, each garden has been divided into four quadrants, with two being occupied by rose gardens and the remaining two by recreational facilities. On the Senate side, these are tennis courts and a cricket pitch. On the Representatives' side, they are tennis courts and a bowling/croquet green. In the 1970s much of the Representatives' gardens were covered by an annex extension to the main building, but this has now been removed and the gardens have been restored. The official reopening was in 2004.

The rose gardens contain a wide variety of specimens, including many old roses and roses donated by prominent Australians and overseas bodies and individuals. Much of the inspiration (and organisation) for this came from the Usher of the Black Rod and later Clerk of the Senate, Robert Broinowski, and the gardens were designed by Rex Hazlewood. They also played major roles in the development of the National Rose Gardens on the other side of King George Terrace.

Extensions

Old Parliament House was only intended to be 'provisional' and so office space was not provided for all members. This shortage of space was compounded by the decision of Prime Minister James Scullin to relocate his principal office from West Block to the building in 1930. This eventually resulted in all ministers, with their departmental staff, being accommodated in the building over time, compounding the office space problem.

The first extensions were made to the rear of the building in 1947 to provide more office space for members. Some further extensions were constructed in 1964. In the 1970s, large extensions were added to both sides of the building and the south-west corner. The front façade was extended in a sympathetic fashion to conform with Murdoch's design. On the Representatives side, larger extensions were required, and a substantial part of the gardens were built over and linked to the main building by a bridge.

The interiors of the 1972–73 extensions reflect fashions of the time, although wooden panelling was used for the walls, in keeping with the older parts of the building, but with an unequivocally 1970s style. On the Representatives side, the extensions necessitated the demolition of the Prime Minister's suite of offices (originally intended for the Speaker) and the original Cabinet Room. The rooms are now left in the condition they were in at the time they were occupied by Bob Hawke, immediately prior to the move to New Parliament House in May 1988. Similar extensions were made on the Senate side, with a new suite of rooms being constructed for the President of the Senate in a similar style.

History

Building a new Parliament

A competition was announced on 30 June 1914 to design Parliament House, with prize money of £7,000. However, due to the start of World War I the next month, the competition was cancelled. It was re-announced in August 1916, but again postponed indefinitely on 24 November 1916. In the meantime, John Smith Murdoch, the Commonwealth's chief architect, worked on the design as part of his official duties. He had little personal enthusiasm for the project, as he felt it was a waste of money and expenditure on it could not be justified at the time. Nevertheless, he designed the building by default.[4] The construction of Old Parliament House was commenced on 28 August 1923[5] and completed in early 1927. It was built by the Commonwealth Department of Works, using tradesmen and materials from all over Australia. The final cost was about £600,000, which was more than three times the original estimate. It was designed to last for a maximum of fifty years until a permanent facility could be built.

In 1923, Canberra was a small, dispersed town with few facilities and no administrative or parliamentary functions. The building of Old Parliament House effectively doubled the town's (very small) population. The workers required for the project and their families were housed in camps and settlements and endured Canberra's harsh weather conditions. Once Parliament commenced sitting in Canberra the transfer of Commonwealth public servants from Melbourne required the construction of suitable housing in the areas of Ainslie, Civic, Forrest (formerly called Blandfordia), Griffith and Kingston.

First decades

.png.webp)

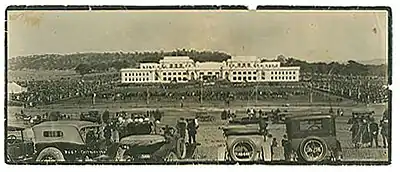

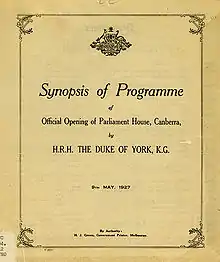

The building was opened on 9 May 1927 by the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George VI and Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother). The opening ceremonies were both splendid and incongruous, given the sparsely built nature of Canberra of the time and its small population. The building was extensively decorated with many Union Jacks and Australian flags and bunting, with similar schemes used at later events, most notably in 1954 when Queen Elizabeth II visited Canberra for the first time and opened Parliament. Temporary stands were erected bordering the lawns in front of the Parliament and these were filled with crowds. A Wiradjuri elder, Jimmy Clements, was one of only two Aboriginal Australians present, having walked for about a week from Brungle Station (near Tumut) to be at the event. Walter Burley Griffin had relocated to Melbourne, and was not given an official invitation to attend the opening. Dame Nellie Melba sang the national anthem (at that time God Save the King). The Duke of York unlocked the front doors with a golden key, and led the official party into King's Hall where he unveiled the statue of his father, King George V, Emperor of India. The Duke then opened the first parliamentary session in the new Senate Chamber.

A large memorial to King George V located immediately opposite Parliament House was unveiled in 1953. This memorial was moved to a nearby location in 1968 to allow a direct line of sight to the Australian War Memorial.[6]

Prime Minister John Curtin, who died in office, and Ben Chifley, a former Prime Minister, both lay in state in King's Hall after their deaths in 1945 and 1951 respectively.

Last decades

On 26 January 1972 four Aboriginal men set up tents and signs in protest about Indigenous land rights in Australia and other Aboriginal rights issues, and called the assemblage the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. In 2022, the embassy celebrated its 50th anniversary and became the longest continuous protest for Indigenous land rights in the world.[7]

In early 1973, the rise of global terrorism in Australia – a particular concern of the new Whitlam government – resulted in considerable angst for the security situation at Parliament. At this time the Prime Minister's office was fitted with bulletproofed glass.[8]

On 11 November 1975, David Smith, Official Secretary to the Governor-General, read a proclamation from the front steps announcing the dissolution of Parliament that followed the dismissal of the Whitlam government by Sir John Kerr; afterwards, Gough Whitlam addressed the crowd and their remarks have become a famous part of Australia's political history.

By the 1970s Old Parliament House had exceeded its capacity and was in need of considerable repair and renovation, especially considering that it was never intended to be a permanent facility and was nearing the end of its useful life. For this reason, in the late 1970s Malcolm Fraser's government committed to the building of a new Parliament House. After the opening of new Parliament House by Queen Elizabeth II on 9 May 1988, Old Parliament House continued to be used for a few weeks. The final session ended when the Senate was adjourned at 12:26 am on Friday 3 June, by the president, Senator Kerry Sibraa.[9] After this, the Old Parliament House was left vacant for several years.

Life after New Parliament House

After Parliament relocated to the new building in 1988, the question of whether to demolish Old Parliament House was debated at length. During the 1920s some, including Walter Burley Griffin, had argued that the building's position would interfere with the vista of a permanent Parliament House. Griffin had likened the placement of the Old Parliament House to "filling the front yard with outhouses" because the building would interfere with the land axis from Mount Ainslie to Capital Hill. After considering the building's significance in the history of twentieth century Australia, however, the government decided that it should remain. It was eventually decided that its most suitable use would be a "living museum of political history".[10]

Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House

The building re-opened in 2009 as the Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House, an executive agency of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Its role is to celebrate democracy and Australia's political history.[2][11]

The Australian Prime Ministers Centre was the first stage of the Museum of Australian Democracy. It "supports research into the history, origins and traditions of Australian democracy, with a particular focus on Australian prime ministers".[12] The Centre offers fellowships to "established researchers and artists interested in the history, origins, traditions and contemporary practice of Australian democracy, with special reference to Australian prime ministers".[13] After funding cuts, the Australian Prime Ministers Centre transferred to an online-only presence in 2016.[14]

Interim National Portrait Gallery

The Library of the Parliament House was opened as the interim National Portrait Gallery, before it moved to a new building in 2009.

Arson attacks

The building was set alight twice during protests staged by so-called sovereign citizens, a movement that rejects elected officials and law enforcement, including the courts. The protesters had tried to infiltrate the Aboriginal Tent Embassy group. Ngunnawal elder Matilda House-Williams, who was present when the site was established in 1972, condemned the fire and said the protest did not represent the embassy or the Indigenous people of Canberra.[15] On 21 December 2021, the front doors were scorched by a fire whose cause was originally thought to be accidental or intentional lighting by protesters.[16] Nine days later, the doors, portico, and façade were all substantially damaged by a larger fire,[17] which was intentionally lit.[18] As of 2022, repairs were under way at an expected cost of more than $5.3 million.[19] Some of those responsible were charged.[15][20]

Engineering heritage award

Both the old and new Parliament House received an Engineering Heritage National Marker from Engineers Australia as part of its Engineering Heritage Recognition Program.[21]

Gallery

The Prime Minister's office

The Prime Minister's office Photograph showing sheep near Parliament House, Canberra, taken by Albert R. Peters in the 1940s

Photograph showing sheep near Parliament House, Canberra, taken by Albert R. Peters in the 1940s John Curtin's casket lay in State in King's Hall, Old Parliament House, July 1945

John Curtin's casket lay in State in King's Hall, Old Parliament House, July 1945 A rare colour lithograph by an unknown artist of the opening of provisional parliament house in Canberra, 9 May 1927

A rare colour lithograph by an unknown artist of the opening of provisional parliament house in Canberra, 9 May 1927 Desk of former Prime Ministers, on show in the Museum of Australian Democracy, Old Parliament House. Used by Prime Ministers from Bruce (1927) to Whitlam (1972), then in the new Parliament House by Howard (1996–2007)

Desk of former Prime Ministers, on show in the Museum of Australian Democracy, Old Parliament House. Used by Prime Ministers from Bruce (1927) to Whitlam (1972), then in the new Parliament House by Howard (1996–2007)

See also

References

- ↑ "Old Parliament House and Curtilage, King George Tce, Parkes, ACT, Australia (Place ID 105318)". Australian Heritage Database. Australian Government. 22 June 2004. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 1 2 "Order to Establish Old Parliament House as an Executive Agency" (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia Gazette. 1 May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ↑ Heritage management plan Archived 18 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine (Warning—this is a PDF file of 11 mB)

- ↑ Messenger, Robert (4 May 2002). "Mythical thing" to an iced reality.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ "Australia's Prime Ministers: Timeline". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Rhodes, Campbell (17 October 2011). "The King George V memorial". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ Wellington, Shahni (23 January 2022). "Indigenous activism heads online as the Aboriginal Tent Embassy celebrates 50 years". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ Coventry, CJ. Origins of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security (2018: MA thesis submitted at UNSW), 134.

- ↑ President's valedictory Archived 6 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Adjournment of the Senate Archived 4 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ To Demolish or Not to Demolish Archived 19 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine at Museum of Australian Democracy, Old Parliament House

- ↑ "Home". Museum of Australian Democracy at Old Parliament House. Archived from the original on 26 February 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ↑ "Prime Ministers". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ "Fellowships". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ↑ Jeffery, Stephen (11 December 2016). "Outside funding pays for new Trove content after National Library cuts". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- 1 2 McIlroy, Tom (20 January 2022). "Aboriginal Tent Embassy: 50 years on, the struggles remain urgent". Australian Financial Review. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ↑ Byrne, Elizabeth (24 December 2021). "Canberra's Old Parliament House forced to close after protesters accidentally set fire to front door". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ Curtis, Katina (30 December 2021). ""Incalculable damage" to heritage after fire at Old Parliament House amid protests". The Sydney Morning Herald. Nine Entertainment Co. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ Seyfort, Serena; Trajkovich, Marina. "Protesters set fire to Old Parliament House in Canberra". Nine News. Nine Entertainment Co. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ↑ Wong, Kat (1 November 2022). "Old Parliament House fire bill hits $5.3m". Newcastle Herald. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ↑ "Multi-million-dollar bill to repair "substantial" fire damage at Old Parliament House in Canberra – ABC News". ABC News. Abc.net.au. 20 January 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ↑ "Parliament Houses, Canberra – 1927". Engineers Australia. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

Notes

- ^ Apperly, Richard; Robert Irving; Peter Reynolds (1989). A pictorial guide to identifying Australian architecture (Paperback, 1994 ed.). Sydney, Australia: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-207-18562-X.

- ^ Charlton, Ken; Rodney Garnett; Shibu Dutta (2001). Federal Capital Architecture Canberra 1911–1939 (2nd Edition, Paperback, 2001 ed.). Canberra, Australia: National Trust of Australia (ACT). ISBN 0-9578541-0-2.

- ^ Metcalf, Andrew (2003). Canberra Architecture (1st Edition, Paperback, 2003 ed.). Sydney, Australia: The Watermark Press. ISBN 0-949284-63-7.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Old Parliament House and Curtilage, King George Tce, Parkes, ACT, Australia, entry number 105318 in the Australian Heritage Database published by the Commonwealth of Australia 2004 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 18 May 2020.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Old Parliament House and Curtilage, King George Tce, Parkes, ACT, Australia, entry number 105318 in the Australian Heritage Database published by the Commonwealth of Australia 2004 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 18 May 2020.

Bibliography

- Australian Construction Service (1988). The building in its setting: Old Parliament House redevelopment.

- Australian Construction Service (1991). Old Parliament House redevelopment study: design drawings.

- Australian Construction Service (1991). Heritage strategy: Old Parliament House redevelopment.

- Australian Construction Service (1991). Architectural character: Old Parliament House redevelopment.

- Australian Construction Service (1995). Conservation management plan: Old Parliament House, Canberra, A.C.T.

- Charlton, Ken (1984). Federal Capital Architecture. National Trust of Australia (ACT).

- Connybeare Morrison & Partners; others (1994). Restoration of Old Parliament House Gardens, Report on History of the Gardens, prepared for the NCPA.

- Conybeare Morrison & Partners (1994). Restoration of Old Parliament House.

- Dick, George (1977). Parliament House Canberra. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Gardens: masterplan report.

- Garnett, Rodney; Hyndes, Danielle (1992). The Heritage of the Australian Capital Territory. National Trust of Australia (ACT) and others.

- Gibbney, Jim (1988). Canberra 1913-1953. Australian Government Publishing Service.

- Gray, J. (1995). Poplar trees in the Garden Courts of Old Parliament House, Canberra: options for replanting.

- Gutteridge Haskins and Davey (1999). Old Parliament House South West Wing Heritage Study, report for the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts.

- Howard Tanner and Associates (1986). Provisional Parliament House: The Conservation Plan.

- Marshall, D. (1995). Documentation on Historic Places in the Australian Capital Territory. Vol. 1–3. Australian Heritage Commission (unpublished).

- Nelsen, Ivar; Waite, Phil (1995). Conservation Management Plan, Old Parliament House, Canberra, ACT. Australian Construction Services.

- O'Keefe, B.; Pearson, M. (1998). Federation: A National Survey of Heritage Places. Australian Heritage Commission.

- O'Keefe, B. (2000). Old Parliament House : heritage study for the conservation and refurbishment of the southwest wing of Old Parliament House.

- Patrick and Wallace (1988). Draft conservation study of Old Parliament House gardens, Canberra.

- Pearson, M.; Betteridge, M.; Marshall, D.; O'Keefe, B.; Young, L. (2000). Old Parliament House Conservation Management Plan. Report prepared for the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts.

- Pryor, L. D.; Banks, J. C. G. (1991). Trees and Shrubs in Canberra. Canberra: Little Hills Press.