| History of Portugal |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The history of Portugal can be traced from circa 400,000 years ago, when the region of present-day Portugal was inhabited by Homo heidelbergensis.

The Roman conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, which lasted almost two centuries, led to the establishment of the provinces of Lusitania in the south and Gallaecia in the north of what is now Portugal. Following the fall of Rome, Germanic tribes controlled the territory between the 5th and 8th centuries, including the Kingdom of the Suebi centred in Braga and the Visigothic Kingdom in the south.

The 711–716 invasion by the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate conquered the Visigoth Kingdom and founded the Islamic State of Al-Andalus, gradually advancing through Iberia. In 1095, Portugal broke away from the Kingdom of Galicia. Afonso Henriques, son of the count Henry of Burgundy, proclaimed himself king of Portugal in 1139. The Algarve (the southernmost province of Portugal) was conquered from the Moors in 1249, and in 1255 Lisbon became the capital. Portugal's land boundaries have remained almost unchanged since then. During the reign of King John I, the Portuguese defeated the Castilians in a war over the throne (1385) and established a political alliance with England (by the Treaty of Windsor in 1386).

From the late Middle Ages, in the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal ascended to the status of a world power during Europe's "Age of Discovery" as it built up a vast empire. Signs of military decline began with the Battle of Alcácer Quibir in Morocco in 1578; this defeat led to the death of King Sebastian and the imprisonment of much of the high nobility, which had to be ransomed at great cost. This eventually led to a small interruption in Portugal's 800-year-old independence by way of a 60-year dynastic union with Spain between 1580 and the beginning of the Portuguese Restoration War led by John IV in 1640. Spain's disastrous defeat in its attempt to conquer England in 1588 by means of the Invincible Armada was also a factor, as Portugal had to contribute ships for the invasion. Further setbacks included the destruction of much of its capital city in an earthquake in 1755, occupation during the Napoleonic Wars, and the loss of its largest colony, Brazil, in 1822. From the middle of the 19th century to the late 1950s, nearly two million Portuguese left Portugal to live in Brazil and the United States.[1]

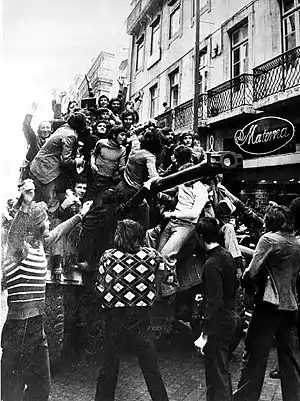

In 1910, a revolution deposed the monarchy. A military coup in 1926 installed a dictatorship that remained until another coup in 1974. The new government instituted sweeping democratic reforms and granted independence to all of Portugal's African colonies in 1975. Portugal is a founding member of NATO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries. It entered the European Economic Community (now the European Union) in 1986.

Etymology

The word Portugal derives from the combined Roman-Celtic place name Portus Cale;[2][3] a settlement where present-day's conurbation of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia (or simply, Gaia) stand, along the banks of river Douro in the north of what is now Portugal.

Porto stems from the Latin word for port or harbour, portus, with the second element Cale's meaning and precise origin being less clear. The mainstream explanation points to an ethnonym derived from the Callaeci also known as the Gallaeci peoples, who occupied the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula.[4] The names Cale and Callaici are the origin of today's Gaia and Galicia.[5][6] Another theory proposes that Cale or Calle is a derivation of the Celtic word for 'port',[7] like the Irish caladh or Scottish Gaelic cala.[8] These explanations, would require the pre-Roman language of the area to have been a branch of Q-Celtic, which is not generally accepted because the region's pre-Roman language was Gallaecian. However, scholars like Jean Markale and Tranoy propose the Celtic branches all share the same origin, and placenames such as Cale, Gal, Gaia, Calais, Galatia, Galicia, Gaelic, Gael, Gaul (Latin: Gallia),[9] Wales, Cornwall, Wallonia and others all stem from one linguistic root.[5][10][11] Cala is sometimes considered not Celtic, but from Late Latin calatum > calad > cala,[12] compare Italian cala, French cale, itself from Occitan cala "cove, small harbour" from a Pre-Indo-European root *kal / *cala[13] (see calanque[13] and maybe Galici-a < Callaeci or Calaeci). Another theory claims it derives from the word Caladunum,[14] in fact an unattested compound *Caladunum, that may explain the toponym Calezun in Gascony.[15]

A further explanation proposes Gatelo as having been the origin of present-day Braga, Santiago de Compostela, and consequently the wider regions of Northern Portugal and Galicia.[16] A different theory has it that Cala was the name of a Celtic goddess (drawing a comparison with the Gaelic Cailleach, a supernatural hag). Some French scholars believe the name may have come from Portus Gallus,[17] the port of the Gauls or Celts.

Around 200 BC, the Romans took the Iberian Peninsula from the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War. In the process they conquered Cale, renaming it Portus Cale ('Port of Cale') and incorporating it in the province of Gaellicia with its capital in Bracara Augusta (modern day Braga, Portugal). During the Middle Ages, the region around Portus Cale became known by the Suebi and Visigoths as Portucale. The name Portucale changed into Portugale during the 7th and 8th centuries. By the 9th century, Portugale was used extensively to refer to the region between the rivers Douro and Minho, the Minho flowing along what would become the northern Portugal–Spain border. By the 11th and 12th centuries, Portugale, Portugallia, Portvgallo or Portvgalliae was already referred to as Portugal.

The 14th-century Middle French name for the country, Portingal, which added an intrusive /n/ sound through the process of excrescence, spread to Middle English.[18] Middle English variant spellings included Portingall, Portingale,[note 1] Portyngale and Portingaill.[18][20] The spelling Portyngale is found in Chaucer's Epilogue to the Nun's Priest's Tale. These variants survive in the Torrent of Portyngale, a Middle English romance composed around 1400, and "Old Robin of Portingale", an English Child ballad. Portingal and variants were also used in Scots[18] and survive in the Cornish name for the country, Portyngal.

Early history

Prehistory

The oldest trace of human history in Portugal.

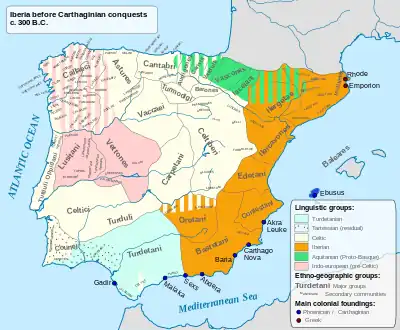

The early history of Portugal is shared with the rest of the Iberian Peninsula located in southwestern Europe. The name of Portugal derives from the joined Romano-Celtic name Portus Cale. The region was settled by Pre-Celts and Celts, giving origin to peoples like the Gallaeci, Lusitanians,[21] Celtici and Cynetes (also known as Conii).[22] Some coastal areas were visited by Phoenicians-Carthaginians and Ancient Greeks. It was incorporated in the Roman Republic dominions as Lusitania and part of Gallaecia, after 45 BC until 298 AD.

The region of present-day Portugal was inhabited by humans since circa 400,000 years ago, when Homo heidelbergensis entered the area. The oldest human fossil found in Portugal is the 400,000-year-old Aroeira 3 H. Heidelbergensis skull discovered in the Cave of Aroeira in 2014.[23] Later Neanderthals roamed the northern Iberian peninsula and a tooth has been found at Nova da Columbeira cave in Estremadura.[24] Homo sapiens sapiens arrived in Portugal around 35,000 years ago, spreading and roaming the border-less region of the northern Iberian peninsula.[24][25] These were subsistence societies and although they did not establish prosperous settlements, they did form organized societies. Neolithic Portugal experimented with domestication of herding animals, the raising of some cereal crops and fluvial or marine fishing.[24]

Pre-Celtic tribes inhabited Portugal leaving a cultural footprint. The Cynetes developed a written language, leaving many stelae, which are mainly found in the south of Portugal. Early in the first millennium BC, waves of Celts invaded Portugal from Central Europe and inter-married with the local populations, forming different tribes.[26] Another theory suggests that Celts inhabited western Iberia / Portugal well before any large Celtic migrations from Central Europe.[27] A number of linguists expert in ancient Celtic have presented compelling evidence that the Tartessian language, once spoken in parts of SW Spain and SW Portugal, is at least proto-Celtic in structure.[28]

The Celtic presence in Portugal is traceable, in broad outline, through archaeological and linguistic evidence. They dominated much of northern and central Portugal; but in the south, they were unable to establish their stronghold, which retained its non-Indo-European character until the Roman conquest.[29] In southern Portugal, some small, semi-permanent commercial coastal settlements were also founded by Phoenician-Carthaginians.

Modern archaeology and research shows a Portuguese root to the Celts in Portugal and elsewhere.[30] During that period and until the Roman invasions, the Castro culture (a variation of the Urnfield culture also known as Urnenfelderkultur) was prolific in Portugal and modern Galicia.[31][32] This culture, together with the surviving elements of the Atlantic megalithic culture[33] and the contributions that come from the more Western Mediterranean cultures, ended up in what has been called the Cultura Castreja or Castro Culture.[34][35] This designation refers to the characteristic Celtic populations called 'dùn', 'dùin' or 'don' in Gaelic and that the Romans called castrae in their chronicles.[36]

.jpg.webp)

Based on the Roman chronicles about the Callaeci peoples, along with the Lebor Gabála Érenn[37] narrations and the interpretation of the archaeological remains throughout the northern half of Portugal and Galicia, it is possible to infer that there was a matriarchal society, with a military and religious aristocracy probably of the feudal type. The figures of maximum authority were the chieftain (chefe tribal), of military type and with authority in his Castro or clan, and the druid, mainly referring to medical and religious functions that could be common to several castros. The Celtic cosmogony remained homogeneous due to the ability of the druids to meet in councils with the druids of other areas, which ensured the transmission of knowledge and the most significant events.

The first documentary references to Castro society are provided by chroniclers of Roman military campaigns such as Strabo, Herodotus and Pliny the Elder among others, about the social organization, and describing the inhabitants of these territories, the Gallaeci of Northern Portugal as: "A group of barbarians who spend the day fighting and the night eating, drinking and dancing under the moon."

There were other similar tribes, and chief among them were the Lusitanians; the core area of these people lay in inland central Portugal, while numerous other related tribes existed such as the Celtici of Alentejo, and the Cynetes or Conii of the Algarve. Among the tribes or sub-divisions were the Bracari, Coelerni, Equaesi, Grovii, Interamici, Leuni, Luanqui, Limici, Narbasi, Nemetati, Paesuri, Quaquerni, Seurbi, Tamagani, Tapoli, Turduli, Turduli Veteres, Turduli Oppidani, Turodi, and Zoelae. A few small, semi-permanent, commercial coastal settlements (such as Tavira) were also founded in the Algarve region by Phoenicians–Carthaginians.

Ancient history

Dolmen of Cerqueira, Sever do Vouga

Dolmen of Cerqueira, Sever do Vouga.jpg.webp) Archaeological artifact from the work developed in the area of Citânia de Briteiros

Archaeological artifact from the work developed in the area of Citânia de Briteiros.jpg.webp) Cross or cruzado in Citânia de Briteiros

Cross or cruzado in Citânia de Briteiros

.jpg.webp) Another artifact from Citânia de Briteiros

Another artifact from Citânia de Briteiros A pedra formosa Celtic triskelion motifs

A pedra formosa Celtic triskelion motifs

Numerous pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula inhabited the territory when a Roman invasion occurred in the 3rd century BC. The Romanization of Hispania took several centuries. The Roman provinces that covered present-day Portugal were Lusitania in the south and Gallaecia in the north.

Numerous Roman sites are scattered around present-day Portugal. Some of the urban remains are quite large, such as Conímbriga and Miróbriga. Several works of engineering, such as baths, temples, bridges, roads, circuses, theatres, and layman's homes are preserved throughout the country. Coins, sarcophagi, and ceramics are also numerous.

Following the fall of Rome, the Kingdom of the Suebi and the Visigothic Kingdom controlled the territory between the 5th and 8th centuries.

Romanization

Romanization began with the arrival of the Roman army in the Iberian Peninsula in 218 BC during the Second Punic War against Carthage. The Romans sought to conquer Lusitania, a territory that included all of modern Portugal south of the Douro river and Spanish Extremadura, with its capital at Emerita Augusta (now Mérida).[38]

Mining was the primary factor that made the Romans interested in conquering the region: one of Rome's strategic objectives was to cut off Carthaginian access to the Iberian copper, tin, gold, and silver mines. The Romans intensely exploited the Aljustrel (Vipasca) and Santo Domingo mines in the Iberian Pyrite Belt which extends to Seville.[39]

While the south of what is now Portugal was relatively easily occupied by the Romans, the conquest of the north was achieved only with difficulty due to resistance from Serra da Estrela by Celts and Lusitanians led by Viriatus, who managed to resist Roman expansion for years.[38] Viriatus, a shepherd from Serra da Estrela who was expert in guerrilla tactics, waged relentless war against the Romans, defeating several successive Roman generals, until he was assassinated in 140 BC by traitors bought by the Romans. Viriatus has long been hailed as the first truly heroic figure in proto-Portuguese history. Nonetheless, he was responsible for raids into the more settled Romanized parts of Southern Portugal and Lusitania that involved the victimization of the inhabitants.[38][40]

The conquest of the Iberian Peninsula was complete two centuries after the Roman arrival, when they defeated the remaining Cantabri, Astures and Gallaeci in the Cantabrian Wars in the time of Emperor Augustus (19 BC). In 74 AD, Vespasian granted Latin Rights to most municipalities of Lusitania. In 212 AD, the Constitutio Antoniniana gave Roman citizenship to all free subjects of the empire and, at the end of the century, the emperor Diocletian founded the province of Gallaecia, which included modern-day northern Portugal, with its capital at Bracara Augusta (now Braga).[38] As well as mining, the Romans also developed agriculture, on some of the best agricultural land in the empire. In what is now Alentejo, vines and cereals were cultivated, and fishing was intensively pursued in the coastal belt of the Algarve, Póvoa de Varzim, Matosinhos, Troia and the coast of Lisbon, for the manufacture of garum that was exported by Roman trade routes to the entire empire. Business transactions were facilitated by coinage and the construction of an extensive road network, bridges and aqueducts, such as Trajan's bridge in Aquae Flaviae (now Chaves).[41]

Roman rule brought geographical mobility to the inhabitants of Portugal and increased their interaction with the rest of the world as well as internally. Soldiers often served in different regions and eventually settled far from their birthplace, while the development of mining attracted migration into the mining areas.[40] The Romans founded numerous cities, such as Olisipo (Lisbon), Bracara Augusta (Braga), Aeminium (Coimbra) and Pax Julia (Beja),[42] and left important cultural legacies in what is now Portugal. Vulgar Latin (the basis of the Portuguese language) became the dominant language of the region, and Christianity spread throughout Lusitania from the third century.

Germanic invasions

The Suebi

In 409, with the decline of the Roman Empire, the Iberian Peninsula was occupied by Germanic tribes that the Romans referred to as barbarians.[43] In 411, with a federation contract with Emperor Honorius, many of these people settled in Hispania. An important group was made up of the Suebi and Vandals in Gallaecia, who founded the Kingdom of the Suebi with its capital in Braga.[44] They came to dominate Aeminium (Coimbra) as well, and there were Visigoths to the south.[45] The Suebi and the Visigoths were the Germanic tribes who had the most lasting presence in the territories corresponding to modern Portugal. As elsewhere in Western Europe, there was a decline in urban life during the Dark Ages.[46]

Roman institutions declined in the wake of the Germanic invasions with the exception of ecclesiastical organizations, which were fostered by the Suebi in the fifth century and adopted by the Visigoths afterwards. Although the Suebi and Visigoths were initially followers of Arianism and Priscillianism, they adopted Catholicism from the local inhabitants. St. Martin of Braga was a particularly influential evangelist at this time.[45]

The Kingdom of the Suebi[47] was the Germanic post-Roman kingdom, established in the former Roman provinces of Gallaecia-Lusitania. 5th-century vestiges of Alan settlements were found in Alenquer (from old Germanic Alan kerk, temple of the Alans), Coimbra and Lisbon.[48]

King Hermeric made a peace treaty with the Gallaecians before passing his domains to Rechila, his son. In 429, the Visigoths moved south to expel the Alans and Vandals and founded a kingdom with its capital in Toledo. In 448 Rechila died, leaving the state in expansion to Rechiar. Subsequently, this new king started to print coins under his own name, becoming the first of the Germanic kings to do so,[49] and then was baptised to Nicene Christianity, probably by the Bishop Balconius, also becoming the first of the Germanic kings to do so, even before Clovis, king of the Franks.[50] This bellicose king, almost conquered the whole of Hispania, taking many prisoners and several important cities, but failed to consolidate his conquest over the territory and didn't even came near Tarragona.

After the assassination of the patrician Flavius Aëtius, Rechiar attempted, yet again,to conquer the whole of the peninsula, however his ambitions were derailed by the invading Visigoths under their king and Roman foederatus Theodoric II acting on the orders of the emperor Avitus. This led to a resounding defeat of the Suebian kingdom, with Rechiar fleeing wounded from Braga, only to be captured at Oporto and executed in December of 456 (d.C.). The realm was then divided, with Frantan and Aguiulfo ruling simultaneously. Both reigned from 456 to 457, the year in which Maldras (457–459) reunified the kingdom. He was assassinated after a failed Roman-Visigothic conspiracy. Although the conspiracy did not achieve its true purposes, the Suebian Kingdom was again divided between two kings: Frumar (Frumario 459–463) and Remismund (Remismundo, son of Maldras) (459–469) who would re-reunify his father's kingdom in 463. He would be forced to adopt Arianism in 465 due to the Visigoth influence. From 470, conflict between the Suebi and Visigoths increased.

The Visigoths

By 500, the Visigothic Kingdom had been installed in Iberia, it was based in Toledo and advancing westwards. They became a threat to the Suebian rule. After the death of Remismund in 469 a dark period set in, where virtually all written texts and accounts disappear. This period lasted until 550. The only thing known about this period is that Theodemund (Teodemundo) most probably ruled the Suebians.

The dark period ended with the reign of Karriarico (550–559) who reinstalled Catholic Christianity in 550. He was succeeded by Theodemar (559–570) during whose reign the 1st Council of Braga (561) was held. After the death of Theodemar, Miro (570–583) was his successor. During his reign, the 2nd Council of Braga (572) was held. The councils represented an advance in the organization of the territory (paroeciam suevorum (Suebian parish) and the Christianization of the pagan population (De correctione rusticorum) under the auspices of Saint Martin of Braga (São Martinho de Braga).[51]

The Visigothic civil war began in 577, in which Miro intervened. Later, in 583, he also organized an unsuccessful expedition to reconquer Seville. During the return from this failed campaign Miro died, thereby ending the proeminence of the Suebi in Hispanic politics, and in two years the kingdom would be conquered by the Visigoths.

In the Suebian Kingdom many internal struggles continued to take place. Eborico (Eurico, 583–584) was dethroned by Andeca (Audeca 584–585), who failed to prevent the Visigothic invasion led by Liuvigild. The Visigothic invasion, completed in 585, turned the once rich and fertile kingdom of the Suebi into the sixth province of the Visigothic kingdom.[52] Leovigild was crowned King of Gallaecia, Hispania and Gallia Narbonensis.

For the next 300 years and by the year 700, the entire Iberian Peninsula was ruled by the Visigoths.[53][54][55][56] With the Visigoths settled in the newly formed kingdom, a new class emerged that had been unknown in Roman times: a nobility, which played a large social and political role during the Middle Ages. It was under the Visigoths that the Church began to play an important part within the state. Since the Visigoths did not learn Latin from the local people, they had to rely on Catholic bishops to continue the Roman system of governance. The laws established during the Visigothic monarchy were thus made by councils of bishops, and the clergy started to emerge as a high-ranking class.

Under the Visigoths, Gallaecia was a well-defined space governed by a doge of its own. Doges at this time were related to the monarchy and acted as princes in all matters. Both 'governors' Wamba and Wittiza (Vitiza) acted as doge (they would later become kings in Toledo). These two became known as the 'vitizians', who headquartered in the northwest and called on the Arab invaders from the South to be their allies in the struggle for power in 711. King Roderic (Rodrigo) was killed while opposing this invasion, thus becoming the last Visigothic king of Iberia. From the various Germanic groups who settled in western Iberia, the Suebi left the strongest lasting cultural legacy in what is today Portugal, Galicia and western fringes of Asturias.[57][58][59] According to Dan Stanislawski, the Portuguese way of living in regions North of the Tagus is mostly inherited from the Suebi, in which small farms prevail, distinct from the large properties of Southern Portugal. Bracara Augusta, the modern city of Braga and former capital of Gallaecia, became the capital of the Suebi.[51] Apart from cultural and some linguistic traces, the Suebians left the highest Germanic genetic contribution of the Iberian Peninsula in Portugal and Galicia.[60] Orosius, at that time resident in Hispania, shows a rather pacific initial settlement, the newcomers working their lands[61] or serving as bodyguards of the locals.[62] Another Germanic group that accompanied the Suebi and settled in Gallaecia were the Buri. They settled in the region between the rivers Cávado and Homem, in the area known as Terras de Bouro (Lands of the Buri).[63]

Al Andalus (711–868)

During the caliphate of the Umayyad Caliph Al-Walid I, commander Tariq ibn-Ziyad led a small force that landed at Gibraltar on 30 April 711, ostensibly to intervene in a Visigothic civil war. After a decisive victory over King Roderic at the Battle of Guadalete on 19 July 711, Tariq ibn-Ziyad, joined by the Arab governor Musa ibn Nusayr of Ifriqiya, brought most of the Visigothic kingdom under Muslim occupation in a seven-year campaign. The Visigothic resistance to this invasion was ineffective, though sieges were required to sack a couple of cities. This is in part because the ruling Visigoth population is estimated at a mere 1 to 2% of the total population.[64] On one hand this isolation is said to have been 'a reasonably strong and effective instrument of government'; on the other, it was highly 'centralised to the extent that the defeat of the royal army left the entire land open to the invaders.[65] The resulting power vacuum, which may have indeed caught Tariq completely by surprise, would have aided the Muslim conquest immensely. Indeed, it may have been equally welcome to the Hispano-Roman peasants who—as D.W. Lomax claims—were disillusioned by the prominent legal, linguistic and social divide between them and the 'barbaric' and 'decadent' Visigoth royalty.[66]

The Visigothic territories included what is today Spain, Portugal, Andorra, Gibraltar, and the southwestern part of France known in ancient times as Septimania. The invading Moors wanted to conquer and convert all of Europe to Islam, so they crossed the Pyrenees to use Visigothic Septimania as a base of operations. Muslims called their conquests in Iberia 'al-Andalus' and in what was to become Portugal, they mainly consisted of the old Roman province of Lusitania (the central and southern regions of the country), while Gallaecia (the northern regions) remained unsubdued. Until the Berber revolt in the 730s, al-Andalus was treated as a dependency of Umayyad North Africa. Subsequently, links were strained until the caliphate was overthrown in the late 740s.[67] The Medieval Muslim Moors, who conquered and destroyed the Christian Visigothic kingdom in the Iberian Peninsula, were a mix of Berbers from North Africa and Arabs from the Middle East.

By 714 Évora, Santarém and Coimbra had been conquered, and two years later Lisbon was in Muslim control. By 718 most of today's Portuguese territory was under Umayyad rule. The Umayyads eventually stopped in Poitiers but Muslim rule in Iberia would last until 1492 with the fall of the Kingdom of Granada. For the next several centuries, much of the Iberian Peninsula remained under Umayyad rule. Much of the populace was allowed to remain Christian, and many of the lesser feudal rulers worked out deals where they would submit to Umayyad rule in order to remain in power. They would pay a jizya tax, kill or turn over rebels, and in return receive support from the central government. But some regions, including Lisbon, Gharb Al-Andalus, and the rest of what would become Portugal, rebelled, succeeded in freeing themselves by the early 10th century

Reconquista

In 718 AD, a Visigothic noble named Pelagius was elected leader by the ousted Visigoth nobles. Pelagius called for the remnant of the Christian Visigothic armies to rebel against the Moors and re-group in the unconquered northern Asturian highlands, better known today as the Cantabrian Mountains, a mountain region in modern northwestern Spain adjacent to the Bay of Biscay.[68] He planned to use the Cantabrian Mountain range as a place of refuge and protection from the invaders and as a springboard to reconquer lands from the Moors. After defeating the Moors in the Battle of Covadonga in 722 AD, Pelagius was proclaimed king to found the Christian Kingdom of Asturias and start the war of reconquest known in Portuguese (and Spanish) as the Reconquista.[68]

Currently, historians and archaeologists generally agree that northern Portugal between the Minho and the Douro rivers kept a significant share of its population, a social and political Christian area that until the late 9th century had no acting state powers. However, in the late 9th century, the region became part of a complex of powers, the Galician-Asturian, Leonese and Portuguese power structures.[69]

The coastal regions in the North were also attacked by Norman and Viking[70][71] raiders mainly from 844. The last great invasion, through the Minho (river), ended with the defeat of Olaf II Haraldsson in 1014 against the Galician nobility who also stopped further advances into the County of Portugal.

Creation of the Country of Portugal

At the end of the 9th century, a small minor county based in the area of Portus Cale was established by Vímara Peres on the orders of King Alfonso III of León, Galicia and Asturias. After annexing the County of Portugal into one of the several counties that made up its realms, King Alfonso III named Vímara Peres as its first count. Since the rule of Count Diogo Fernandes, the county increased in size and importance and, from the 10th century onward, with Count Gonçalo Mendes as Magnus Dux Portucalensium (Grand Duke of the Portuguese), the Portuguese counts started using the title of duke, indicating even larger importance and territory. The region became known simultaneously as Portucale, Portugale, and Portugalia—the County of Portugal.[72] The Kingdom of Asturias was later divided as a result of dynastic disputes; the northern region of Portugal became part of the Kingdom of Galicia and later part of the Kingdom of León.

Suebi-Visigothic arts and architecture, in particular sculpture, had shown a natural continuity with the Roman period. With the Reconquista, new artistic trends took hold, with Galician-Asturian influences more visible than the Leonese. The Portuguese group was characterized by a general return to classicism. The county courts of Viseu and Coimbra played a very important role in this process. Mozarabic architecture was found in the south, in Lisbon and beyond, while in the Christian realms Galician-Portuguese and Asturian architecture prevailed.[69]

As a vassal of the Kingdom of León, Portugal grew in power and territory and occasionally gained de facto independence during weak Leonese reigns; Count Mendo Gonçalves even became regent of the Kingdom of Leon between 999 and 1008. In 1070, the Portuguese Count Nuno Mendes desired the Portuguese title and fought the Battle of Pedroso on 18 February 1071 with Garcia II of Galicia, who gained the Galician title, which included Portugal, after the 1065 partition of the Leonese realms. The battle resulted in Nuno Mendes' death and the declaration of Garcia as King of Portugal, the first person to claim this title.[73] Garcia styled himself as "King of Portugal and Galicia" (Garcia Rex Portugallie et Galleciae). Garcia's brothers, Sancho II of Castile and Alfonso VI of Leon, united and annexed Garcia's kingdom in 1071 as well. They agreed to split it among themselves; however, Sancho was killed by a noble the next year. Alfonso took Castile for himself and Garcia recovered his kingdom of Portugal and Galicia. In 1073, Alfonso VI gathered all power, and beginning in 1077, styled himself Imperator totius Hispaniæ (Emperor of All Hispania). When the emperor died, the Crown was left to his daughter Urraca, while his illegitimate daughter Teresa inherited the County of Portugal; in 1095, Portugal broke away from the Kingdom of Galicia. Its territories, consisting largely of mountains, moorland and forests, were bounded on the north by the Minho River, and on the south by the Mondego River.

Foundation of the Kingdom of Portugal

At the end of the 11th century, the Burgundian knight Henry became count of Portugal and defended its independence by merging the County of Portugal and the County of Coimbra. His efforts were assisted by a civil war that raged between León and Castile and distracted his enemies. Henry's son Afonso Henriques took control of the county upon his death. The city of Braga, the unofficial Catholic centre of the Iberian Peninsula, faced new competition from other regions. Lords of the cities of Coimbra and Porto fought with Braga's clergy and demanded the independence of the reconstituted county.

Portugal traces its national origin to 24 June 1128, the date of the Battle of São Mamede. Afonso proclaimed himself Prince of Portugal after this battle and in 1139, he assumed the title King of Portugal. In 1143, the Kingdom of León recognised him as King of Portugal by the Treaty of Zamora. In 1179, the papal bull Manifestis Probatum of Pope Alexander III officially recognised Afonso I as king. After the Battle of São Mamede, the first capital of Portugal was Guimarães, from which the first king ruled. Later, when Portugal was already officially independent, he ruled from Coimbra.

Affirmation of Portugal

The Algarve, the southernmost region of Portugal, was finally conquered from the Moors in 1249, and in 1255 the capital shifted to Lisbon.[74] Spain finally completed its Reconquista until 1492, almost 250 years later.[75] Portugal's land boundaries have been notably stable for the rest of the country's history. The border with Spain has remained almost unchanged since the 13th century. The Treaty of Windsor (1386) created an alliance between Portugal and England that remains in effect to this day. Since early times, fishing and overseas commerce have been the main economic activities.

In 1383, John I of Castile, husband of Beatrice of Portugal and son-in-law of Ferdinand I of Portugal, claimed the throne of Portugal. A faction of petty noblemen and commoners, led by John of Aviz (later King John I of Portugal) and commanded by General Nuno Álvares Pereira defeated the Castilians in the Battle of Aljubarrota. With this battle, the House of Aviz became the ruling house of Portugal.

The new ruling dynasty would proceed to push Portugal to the limelight of European politics and culture, creating and sponsoring works of literature, like the Crónicas d'el Rei D. João I by Fernão Lopes, the first riding and hunting manual Livro da ensinança de bem cavalgar toda sela and O Leal Conselheiro both by King Edward of Portugal[76][77][78] and the Portuguese translations of Cicero's De Oficiis and Seneca's De Beneficiis by the well traveled Prince Peter of Coimbra, as well as his magnum opus Tratado da Vertuosa Benfeytoria.[79] In an effort of solidification and centralization of royal power the monarchs of this dynasty also ordered the compilation, organization and publication of the first three compilations of laws in Portugal: the Ordenações d'el Rei D. Duarte,[80] which was never enforced; the Ordenações Afonsinas, whose application and enforcement was not uniform across the realm; and the Ordenações Manuelinas, which took advantage of the printing press to reach every corner of the kingdom. The Avis Dynasty also sponsored works of architecture like the Mosteiro da Batalha (literally, the Monastery of the Battle) and led to the creation of the manueline style of architecture in the 16th century.

Naval exploration and Portuguese Empire (15th–16th centuries)

During the 15th and 16th centuries, Portugal became a leading European power that ranked with England, France and Spain in terms of economic, political and cultural influence. Though not dominant in European affairs, Portugal did have an extensive colonial trading empire throughout the world backed by a powerful thalassocracy.

The beginnings of the Portuguese Empire can be traced to 25 July 1415, when the Portuguese Armada set sail for the rich Islamic trading center of Ceuta in North Africa. The Armada was accompanied by King John I, his sons Prince Duarte (a future king), Prince Pedro, and Prince Henry the Navigator, and the legendary Portuguese hero Nuno Álvares Pereira.[81] On 21 August 1415, Ceuta was conquered by Portugal, and the long-lived Portuguese Empire was founded.[82]

The conquest of Ceuta was facilitated by a major civil war that had been engaging the Muslims of the Maghreb (North Africa) since 1411.[82] This civil war prevented a re-capture of Ceuta from the Portuguese, when the king of Granada Muhammed IX, the Left-Handed, laid siege to Ceuta and attempted to coordinate forces in Morocco and attract aid and assistance for the effort from Tunis.[83] The Muslim attempt to retake Ceuta was ultimately unsuccessful and Ceuta remained the first part of the new Portuguese Empire.[83] Further steps were taken that soon expanded the Portuguese Empire much further.

In 1418, two of Prince Henry the Navigator's captains, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira, were driven by a storm to an island that they called Porto Santo ("Holy Port") in gratitude for their rescue from the shipwreck. In 1419, João Gonçalves Zarco disembarked on the Island of Madeira. Uninhabited Madeira was colonized by the Portuguese in 1420.[83]

Between 1427 and 1431, most of the Azores were discovered and these uninhabited islands were colonized by the Portuguese in 1445. Portuguese expeditions may have attempted to colonize the Canary Islands as early as 1336, but the Crown of Castile objected to any Portuguese claim to them. Castile began its own conquest of the Canaries in 1402. Castile expelled the last Portuguese from the Canary islands in 1459, and they eventually became part of the Spanish Empire.[84]

In 1434, Gil Eanes passed Cape Bojador, south of Morocco. The trip marked the beginning of the Portuguese exploration of Africa. Before this event, very little was known in Europe about what lay beyond the cape. At the end of the 13th century and the beginning of the 14th, those who tried to venture there became lost, which gave birth to legends of sea monsters. Some setbacks occurred: in 1436 the Canaries were officially recognized as Castilian by the pope—earlier they had been recognized as Portuguese; in 1438, the Portuguese were defeated in a military expedition to Tangier.

These setbacks did not deter the Portuguese from pursuing their exploratory efforts. In 1448, on the small island of Arguim off the coast of Mauritania, an important castle was built to function as a feitoria, or trading post, for commerce with inland Africa. Some years before, the first African gold was brought to Portugal that circumvented the Arab caravans that crossed the Sahara. Some time later, the caravels explored the Gulf of Guinea, which led to the discovery of several uninhabited islands: Cape Verde, São Tomé, Príncipe and Annobón.[85]

On 13 November 1460, Prince Henry the Navigator died.[86] He had been the leading patron of maritime exploration by Portugal and immediately following his death, exploration lapsed. Henry's patronage had shown that profits could be made from the trade that followed the discovery of new lands. Accordingly, when exploration commenced again, private merchants led the way in attempting to stretch trade routes further down the African coast.[86]

In the 1470s, Portuguese trading ships reached the Gold Coast.[86] In 1471, the Portuguese captured Tangier, after years of attempts. Eleven years later, the fortress of São Jorge da Mina in the town of Elmina on the Gold Coast in the Gulf of Guinea was built. Christopher Columbus set sail aboard the fleet of ships taking materials and building crews to Elmina in December 1481. In 1483, Diogo Cão reached and explored the Congo River.

Discovery of the sea route to India and the Treaty of Tordesillas

In 1484, Portugal officially rejected Columbus' idea of reaching India from the west, because it was seen as unfeasible. Some historians have claimed that the Portuguese had already performed fairly accurate calculations concerning the size of the world and therefore knew that sailing west to reach the Indies would require a far longer journey than navigating to the east. However, this continues to be debated. Thus began a long-lasting dispute that eventually resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas with Castile in 1494. The treaty divided the (largely undiscovered) New World equally between the Portuguese and the Castilians, along a north–south meridian line 370 leagues (1770 km/1100 miles) west of the Cape Verde islands, with all lands to the east belonging to Portugal and all lands to the west to Castile.

With the expedition beyond the Cape of Good Hope by Bartolomeu Dias in 1487,[87] the richness of India was now accessible. Indeed, the cape takes its name from the promise of rich trade with the east. Between 1498 and 1501, Pêro de Barcelos and João Fernandes Lavrador explored North America. At the same time, Pêro da Covilhã reached Ethiopia by land. Vasco da Gama sailed for India and arrived at Calicut on 20 May 1498, returning in glory to Portugal the next year.[86] The Monastery of Jerónimos was built, dedicated to the discovery of the route to India.

At the end of the 15th century, Portugal expelled some local Sephardic Jews, along with those refugees who had come from Castile and Aragon after 1492. In addition, many Jews were forcibly converted to Catholicism and remained as conversos. Many Jews remained secretly Jewish, in danger of persecution by the Portuguese Inquisition. In 1506, 3,000 New Christians were massacred in Lisbon.[88]

In the spring of 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral set sail from Cape Verde with 13 ships and crews and nobles such as Nicolau Coelho; the explorer Bartolomeu Dias and his brother Diogo; Duarte Pacheco Pereira (author of the Esmeraldo); nine chaplains; and some 1,200 men.[89] From Cape Verde, they sailed southwest across the Atlantic. On 22 April 1500, they caught sight of land in the distance.[89] They disembarked and claimed this new land for Portugal. This was the coast of what later became the Portuguese colony of Brazil.[89]

The real goal of the expedition, however, was to open sea trade to the empires of the east. Trade with the east had effectively been cut off since the Conquest of Constantinople in 1453. Accordingly, Cabral turned away from exploring the coast of the new land of Brazil and sailed southeast, back across the Atlantic and around the Cape of Good Hope. Cabral reached Sofala on the east coast of Africa in July 1500.[89] In 1505, a Portuguese fort was established here and the land around the fort later formed the Portuguese colony of Mozambique.[90]

Cabral's fleet then sailed east and landed in Calicut in India in September 1500.[91] Here they traded for pepper and, more significantly, opened European sea trade with the empires of the east. No longer would the Muslim Ottoman occupation of Constantinople form a barrier between Europe and the east. Ten years later, in 1510, Afonso de Albuquerque, after attempting and failing to capture and occupy Zamorin's Calicut militarily, conquered Goa on the west coast of India.[92]

João da Nova discovered Ascension Island in 1501 and Saint Helena in 1502; Tristão da Cunha was the first to sight the archipelago still known by his name in 1506. In 1505, Francisco de Almeida was engaged to improve Portuguese trade with the far east. Accordingly, he sailed to East Africa. Several small Islamic states along the coast of Mozambique—Kilwa, Brava and Mombasa—were destroyed or became subjects or allies of Portugal.[93] Almeida then sailed on to Cochin, made peace with the ruler and built a stone fort there.[93]

Portuguese Empire

By the 16th century, the two million people who lived in the original Portuguese lands ruled a vast empire with many millions of inhabitants in the Americas, Africa, the Middle East and Asia. From 1514, the Portuguese had reached China and Japan. In the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea, one of Cabral's ships discovered Madagascar (1501), which was partly explored by Tristão da Cunha (1507); Mauritius was discovered in 1507, Socotra occupied in 1506, and in the same year, Lourenço de Almeida visited Ceylon.

In the Red Sea, Massawa was the most northerly point frequented by the Portuguese until 1541, when a fleet under Estevão da Gama penetrated as far as Suez. Hormuz, in the Persian Gulf, was seized by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1515, who also entered into diplomatic relations with Persia. In 1521, a force under Antonio Correia conquered Bahrain and ushered in a period of almost 80 years of Portuguese rule of the Persian Gulf archipelago[94]

On the Asiatic mainland, the first trading stations were established by Pedro Álvares Cabral at Cochin and Calicut (1501). More important were the conquests of Goa (1510) and Malacca (1511) by Afonso de Albuquerque, and the acquisition of Diu (1535) by Martim Afonso de Sousa. East of Malacca, Albuquerque sent Duarte Fernandes as envoy to Siam (now Thailand) in 1511 and dispatched to the Moluccas two expeditions (1512, 1514), which founded the Portuguese dominion in Maritime Southeast Asia.[95] The Portuguese established their base in the Spice Islands on the island of Ambon.[96] Fernão Pires de Andrade visited Canton in 1517 and opened up trade with China, where, in 1557, the Portuguese were permitted to occupy Macau. Japan, accidentally reached by three Portuguese traders in 1542, soon attracted large numbers of merchants and missionaries. In 1522, one of the ships in the expedition that Ferdinand Magellan organized in the Spanish service completed the first circumnavigation of the globe.

1580 succession crisis, Iberian Union and decline of the Empire

On 4 August 1578, while fighting in Morocco, young King Sebastian died in the Battle of Alcácer Quibir without an heir.[97] The late king's elderly great-uncle, Cardinal Henry, then became king.[98] Henry I died a mere two years later, on 31 January 1580.[99][100] The death of the latter, without any appointed heirs, led to the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580.[101] Portugal was worried about the maintenance of its independence and sought help to find a new king.

One of the claimants to the throne, António, Prior of Crato, a bastard son of Infante Louis, Duke of Beja, and only grandson through the male line of king Manuel I of Portugal, lacked support from the clergy and most of the nobility, but was acclaimed as king in Santarém and in some other towns in June 1580.[102][103]

Philip II of Spain, through his mother Isabella of Portugal, also a grandson of Manuel I, claimed the Portuguese throne and did not recognize António as king of Portugal. The king appointed Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, as captain general of his army.[104] The duke was 73 years old and ill at the time,[105] but Fernando mustered his forces, estimated at 20,000 men,[106] in Badajoz, and in June 1580 crossed the Spanish-Portuguese border and moved towards Lisbon.

The Duke of Alba met little resistance and in July set up his forces at Cascais, west of Lisbon. By mid-August, the Duke was only 10 kilometers from the city. West of the small brook Alcântara, the Spanish encountered a Portuguese force on the eastern side of it, commanded by António, Prior of Crato (a grandson of King Manuel I of Portugal who had proclaimed himself king), and his lieutenant Francisco de Portugal, 3rd Count of Vimioso. In late August, the Duke of Alba defeated António's force, a ragtag army assembled in a hurry and composed mainly of local peasants, and freed slaves at the Battle of Alcântara.[107] This battle ended in a decisive victory for the Spanish army, both on land and sea. Two days later, the Duke of Alba captured Lisbon, and on 25 March 1581, Philip II of Spain was crowned King of Portugal in Tomar as Philip I. This cleared the way for Philip to create an Iberian Union spanning all of Iberia under the Spanish crown.[108]

Philip rewarded the Duke of Alba with the titles of 1st Viceroy of Portugal on 18 July 1580 and Constable of Portugal in 1581. With these titles, the Duke of Alba represented the Spanish monarch in Portugal and was second in hierarchy only after King Philip in Portugal. He held both titles until his death in 1582.[109] The Portuguese and Spanish Empires came under a single rule, but resistance to Spanish rule in Portugal did not come to an end. The Prior of Crato held out in the Azores until 1583, and he continued to seek to recover the throne actively until his death in 1595. Impostors claimed to be King Sebastian in 1584, 1585, 1595 and 1598. "Sebastianism", the myth that the young king will return to Portugal on a foggy day, has prevailed until modern times.

Decline of the Portuguese Empire under the Philippine Dynasty

After the 16th century, Portugal gradually saw its wealth and influence decrease. Portugal was officially an autonomous state, but in actuality, the country was in a personal union with the Spanish crown from 1580 to 1640.[110] The Council of Portugal remained independent inasmuch as it was one of the key administrative units of the Castilian monarchy, legally on equal terms with the Council of the Indies.[111] The joining of the two crowns deprived Portugal of a separate foreign policy, and the enemies of Spain became the enemies of Portugal. England had been an ally of Portugal since the Treaty of Windsor in 1386, but war between Spain and England led to a deterioration of the relations with Portugal's oldest ally and the loss of Hormuz in 1622. From 1595 to 1663, the Dutch–Portuguese War led to invasions of many countries in Asia and competition for commercial interests in Japan, Africa and South America. In 1624, the Dutch seized Salvador, the capital of Brazil;[112] in 1630, they seized Pernambuco in northern Brazil.[112] A treaty of 1654 returned Pernambuco to Portuguese control, however.[113] Both the English and the Dutch continued to aspire to dominate both the Atlantic slave trade and the spice trade with the Far East.

The Dutch intrusion into Brazil was long-lasting and troublesome to Portugal. The Dutch captured the entire coast except that of Bahia and much of the interior of the contemporary Northeastern Brazilian states of Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte and Ceará, while Dutch privateers sacked Portuguese ships in both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Beginning with a major Spanish–Portuguese military operation in 1625, this trend was reversed, and it laid the foundations for the recovery of remaining Dutch-controlled areas. The other smaller, less developed areas were recovered in stages and relieved of Dutch piracy in the next two decades by local resistance and Portuguese expeditions. After the dissolution of the Iberian Union in 1640, Portugal would re-establish its authority over some lost territories of the Portuguese Empire.

Portuguese Restoration War (1640–1668)

.png.webp)

At home, there was peace under the first two Spanish kings, Philip II and Philip III. They maintained Portugal's status, gave positions to Portuguese nobles in the Spanish courts, and Portugal maintained an independent law, currency and government. It was proposed to move the Spanish capital to Lisbon. Later, Philip IV tried to make Portugal a Spanish province, and Portuguese nobles lost power.

Because of this, as well as the general strain on the finances of the Spanish throne as a result of the Thirty Years' War, the Duke of Braganza, one of the native noblemen and a descendant of King Manuel I, was proclaimed King of Portugal as John IV on 1 December 1640, and a war of independence against Spain was launched. The governors of Ceuta did not accept the new king; rather, they maintained their allegiance to Philip IV and Spain. The Portuguese Restoration War ended the sixty-year period of the Iberian Union under the House of Habsburg. This was the beginning of the House of Braganza, which reigned in Portugal until 1910.

King John IV's eldest son came to reign as Afonso VI, however his physical and mental disabilities left him overpowered by Luís de Vasconcelos e Sousa, 3rd Count of Castelo Melhor. In a palace coup organized by the King's wife, Maria Francisca of Savoy, and his brother, Pedro, Duke of Beja, King Afonso VI was declared mentally incompetent and exiled first to the Azores, and then to the Royal Palace of Sintra, outside Lisbon. After Afonso's death, Pedro came to the throne as King Pedro II. Pedro's reign saw the consolidation of national independence, imperial expansion, and investment in domestic production.

Pedro II's son, John V, saw a reign characterized by the influx of gold into the coffers of the royal treasury, supplied largely by the royal fifth (a tax on precious metals), that was received from the Portuguese colonies of Brazil and Maranhão. Disregarding traditional Portuguese institutions of governance, John V acted as an absolute monarch, nearly depleting the country's tax revenues on ambitious architectural works, most notably Mafra Palace, and on commissions and additions for his sizeable art and literary collections.

Owing to his craving for international diplomatic recognition, John also spent large sums on the embassies he sent to the courts of Europe, the most famous being those he sent to Paris in 1715 and Rome in 1716.

Official estimates – and most estimates made so far – place the number of Portuguese migrants to Colonial Brazil during the gold rush of the 18th century at 600,000.[114] This represented one of the largest movements of European populations to their colonies in the Americas during colonial times. From 1709, John V prohibited emigration, since Portugal had lost a sizable proportion of its population. Brazil was elevated to a vice-kingdom.

Pombaline era

In 1738, Sebastião de Melo, the talented son of a Lisbon squire, began a diplomatic career as the Portuguese Ambassador in London and later in Vienna. The Queen regent of Portugal, Maria Anna of Austria, was fond of De Melo; and after his first wife died, she arranged the widowed de Melo's second marriage to the daughter of the Austrian field marshal Leopold Josef, Count von Daun. King John V of Portugal however, was not pleased and recalled Melo to Portugal in 1749. John V died the following year, and his son Joseph I of Portugal was crowned. In contrast to his father, Joseph I was fond of de Melo, and with the Maria Anna's approval, he appointed Melo as Minister of Foreign Affairs. As the king's confidence in de Melo increased, he entrusted him with more control of the state.

By 1755, Sebastião de Melo was made prime-minister. Impressed by British economic success he had witnessed while ambassador, he successfully implemented similar economic policies in Portugal. He abolished slavery in Portugal and in the Portuguese colonies in India; reorganized the army and the navy; restructured the University of Coimbra; and ended discrimination against different Christian sects in Portugal.

But Sebastião de Melo's greatest reforms were economic and financial, with the creation of several companies and guilds to regulate every commercial activity. He demarcated the region for production of port to ensure the wine's quality, and this was the first attempt to control wine quality and production in Europe. He ruled with a strong hand by imposing strict law on all classes of Portuguese society, from the high nobility to the poorest working class, along with a widespread review of the country's tax system. These reforms gained him enemies in the upper classes, especially among the high nobility, who despised him as a social upstart.

Disaster fell upon Portugal in the morning of 1 November 1755, when Lisbon was struck by a violent earthquake with an estimated Richter scale magnitude of 9. The city was razed to the ground by the earthquake and the subsequent tsunami and fires. De Melo survived by a stroke of luck and immediately embarked on rebuilding the city, with his famous quote: "What now? We bury the dead and feed the living."

Despite the natural disaster, Lisbon's population suffered no epidemics and within less than one year the city was being rebuilt. The new Lisbon downtown was designed to resist subsequent earthquakes. Architectural models were built for tests, and the effects of an earthquake were simulated by marching troops around the models. The buildings and big squares of the Pombaline Downtown of Lisbon still remain as one of Lisbon's tourist attractions: they represent the world's first Earthquake-resistant structures.[115] Sebastião de Melo also made an important contribution to the study of seismology by designing an inquiry that was sent to every parish in the country.

Following the earthquake, Joseph I gave his prime minister even more power, and Sebastião de Melo became a powerful, progressive dictator. As his power grew, his enemies increased in number, and bitter disputes with the high nobility became frequent. In 1758, Joseph I was wounded in an attempted assassination. The Távora family and the Duke of Aveiro were implicated and executed after a quick trial. The Jesuits were expelled from the country and their assets confiscated by the crown. Sebastião de Melo showed no mercy and prosecuted every person involved, even women and children. This was the final stroke that broke the power of the aristocracy and ensured the victory of the minister against his enemies. Based upon his swift resolve, Joseph I made his loyal minister Count of Oeiras in 1759.

Following the Távora affair, the new Count of Oeiras knew no opposition. Made "Marquis of Pombal" in 1770, he effectively ruled Portugal until Joseph I's death in 1779. However, historians also argue that Pombal's "enlightenment" and economic progress, while far-reaching, was primarily a mechanism for enhancing autocracy at the expense of individual liberty and an apparatus for crushing opposition, suppressing criticism, furthering colonial exploitation, intensifying book censorship and consolidating personal control and profit.[116]

The new ruler, Queen Maria I of Portugal, disliked the Marquis (See Távora affair), and forbade him from coming within 20 miles of her, thus curtailing his influence.

Portuguese-led invasion of Spain in 1707

In 1707, as part of the War of the Spanish Succession, a joint Portuguese, Dutch, and British army, led by the Marquis of Minas, António Luís de Sousa, conquered Madrid and acclaimed the Archduke Charles of Austria as King Charles III of Spain. Along the route to Madrid, the army led by the Marquis of Minas was successful in conquering Ciudad Rodrigo and Salamanca. Later in the following year, Madrid was reconquered by Spanish troops loyal to the Bourbons.[117]

The Ghost War

In 1762, France and Spain tried to urge Portugal to join the Bourbon Family Compact by claiming that Great Britain had become too powerful due to its successes in the Seven Years' War. Joseph refused to accept and maintained that his 1704 alliance with Britain was no threat.

In spring 1762, Spanish and French troops invaded Portugal from the north as far as the Douro, while a second column sponsored the Siege of Almeida, captured the city, and threatened to advance on Lisbon. The arrival of a force of British troops helped the Portuguese army commanded by the Count of Lippe by blocking the Franco-Spanish advance and driving them back across the border following the Battle of Valencia de Alcántara. At the Treaty of Paris in 1763, Spain agreed to hand Almeida back to Portugal.

Crises of the nineteenth century

Napoleonic era

With the invasions by Napoleon, Portugal began a decline that lasted until the 20th century, it was hastened by the independence of Brazil in 1822, the country's largest colonial possession.

In 1807, Portugal refused Napoleon Bonaparte's demand to accede to the Continental System of embargo against the United Kingdom; a French invasion under General Junot followed, and Lisbon was captured on 8 December 1807. British intervention in the Peninsular War helped in maintaining Portuguese independence. During the war, João VI of Portugal, the prince regent, transferred his court, including Maria I, to the Portuguese territory of Brazil, and established Rio de Janeiro as the capital of the Portuguese Empire. This episode is known as the Transfer of the Portuguese Court to Brazil. The last French troops were expelled in 1812. The war cost Portugal the town of Olivença,[118] now governed by Spain. In 1815, Brazil was declared a Kingdom and the Kingdom of Portugal was united with it, forming a pluricontinental state, the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.

As a result of the change in its status and arrival of the Portuguese royal family, Brazilian administrative, civic, economical, military, educational, and scientific apparatus were expanded and highly modernized. By 1815 the situation in Europe had cooled down sufficiently that João VI would have been able to return safely to Lisbon. However, the King of Portugal remained in Brazil until the Liberal Revolution of 1820, which started in Porto, demanded his return to Lisbon in 1821.

Thus he returned to Portugal but left his son Pedro in charge of Brazil. When the Portuguese Government attempted the following year to return the Kingdom of Brazil to subordinate status, his son Pedro, with the overwhelming support of the Brazilian elites, declared Brazil's independence from Portugal. Cisplatina (today's sovereign state of Uruguay), in the south, was one of the last additions to the territory of Brazil under Portuguese rule.

Brazilian independence was recognized in 1825, whereby Emperor Pedro I granted to his father the titular honour of Emperor of Brazil. John VI's death in 1826 caused serious questions in his succession. Though Pedro was his heir, and reigned briefly as Pedro IV, his status as a Brazilian monarch was seen as an impediment to holding the Portuguese throne by both nations. Pedro abdicated in favour of his daughter, Maria II. However, Pedro's brother, Infante Miguel, claimed the throne in protest. After a proposal for Miguel and Maria to marry failed, Miguel seized power as King Miguel I, in 1828. In order to defend his daughter's rights to the throne, Pedro launched the Liberal Wars to reinstall his daughter and establish a constitutional monarchy in Portugal. The war ended in 1834, with Miguel's defeat, the promulgation of a constitution, and the reinstatement of Queen Maria II.

After 1815, the Portuguese expanded their trading ports along the African coast, moving inland to take control of Angola and Mozambique. The slave trade was abolished in 1836, in part because many foreign slave ships were flying the Portuguese flag. In Portuguese India, trade flourished in the colony of Goa, with its subsidiary colonies of Macau, near Hong Kong on the China coast, and Timor, north of Australia. The Portuguese successfully introduced Catholicism and the Portuguese language into their colonies, while most settlers continued to head to Brazil.[119][120]

Constitutional monarchy

.jpg.webp)

Queen Maria II (Mary II) and King Ferdinand II's son, King Pedro V (Peter V) modernized the country during his short reign (1853–1861). Under his reign, roads, telegraphs, and railways were constructed and improvements in public health advanced. His popularity increased when, during the cholera outbreak of 1853–1856, he visited hospitals handing out gifts and comforting the sick. Pedro's reign was short, as he died of cholera in 1861, after a series of deaths in the royal family, including his two brothers Infante Fernando and Infante João, Duke of Beja, and his wife, Stephanie of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. Pedro not having children, his brother, Luís I of Portugal (Louis I) ascended the throne and continued his modernization.

At the height of European colonialism in the 19th century, Portugal had already lost its territory in South America and all but a few bases in Asia. Luanda, Benguela, Bissau, Lourenço Marques, Porto Amboim and the Island of Mozambique were among the oldest Portuguese-founded port cities in its African territories. During this phase, Portuguese colonialism focused on expanding its outposts in Africa into nation-sized territories to compete with other European powers there.

With the Conference of Berlin of 1884, Portuguese territories in Africa had their borders formally established on request of Portugal in order to protect the centuries-long Portuguese interests in the continent from rivalries enticed by the Scramble for Africa. Portuguese towns and cities in Africa like Nova Lisboa, Sá da Bandeira, Silva Porto, Malanje, Tete, Vila Junqueiro, Vila Pery and Vila Cabral were founded or redeveloped inland during this period and beyond. New coastal towns like Beira, Moçâmedes, Lobito, João Belo, Nacala and Porto Amélia were also founded. Even before the turn of the 20th century, railway tracks as the Benguela railway in Angola, and the Beira railway in Mozambique, started to be built to link coastal areas and selected inland regions.

The 1890 British Ultimatum was delivered to Portugal on 11 January of that year, an attempt to force the retreat of Portuguese military forces in the land between the Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola (most of present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia). The area had been claimed by Portugal, which included it in its "Pink Map", but this clashed with British aspirations to create a Cape to Cairo Railway, thereby linking its colonies from the north of Africa to the far south. This diplomatic clash led to several waves of protest and prompted the downfall of the Portuguese government. The 1890 British Ultimatum was considered by Portuguese historians and politicians at that time to be the most outrageous and infamous action of the British against her oldest ally.[121] It is considered directly responsible for the 31 January 1891 revolt, an attempted Republican coup that took place in Porto.[122]

The Portuguese territories in Africa were Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Portuguese Guinea, Angola, and Mozambique. The tiny fortress of São João Baptista de Ajudá on the coast of Dahomey, was also under Portuguese rule. In addition, Portugal still ruled the Asian territories of Portuguese India, Portuguese Timor and Portuguese Macau.

On 1 February 1908, King Dom Carlos I of Portugal and his heir apparent and his eldest son, Prince Royal Dom Luís Filipe, Duke of Braganza, were assassinated in Lisbon in the Terreiro do Paço by two Portuguese republican activist revolutionaries, Alfredo Luís da Costa and Manuel Buíça. Under his rule, Portugal had been declared bankrupt twice – first on 14 June 1892, and then again on 10 May 1902 – causing social turmoil, economic disturbances, angry protests, revolts and criticism of the monarchy. His second and youngest son, Manuel II of Portugal, became the new king, but was eventually overthrown by the 5 October 1910 Portuguese republican revolution, which abolished the monarchy and installed a republican government in Portugal, causing him and his royal family to flee into exile in London, England.

The First Republic (1910–1926)

The First Republic has, over the course of the recent past, been neglected by many historians in favor of the Estado Novo. As a result, it is difficult to attempt a global synthesis of the republican period in view of the important gaps that still persist in our knowledge of its political history. As far as the 5 October 1910 Revolution is concerned, a number of valuable studies have been made,[123] first among which ranks Vasco Pulido Valente's polemical thesis. This historian posited the Jacobin and urban nature of the revolution carried out by the Portuguese Republican Party (PRP) and claimed that the PRP had turned the republican regime into a de facto dictatorship.[124] This vision clashes with an older interpretation of the First Republic as a progressive and increasingly democratic regime that presented a clear contrast to António de Oliveira Salazar's ensuing dictatorship.[125]

Religion

The First Republic was intensely anti-clerical. It was secularist and followed the liberal tradition of disestablishing the powerful role that the Catholic Church once held. Historian Stanley Payne points out, "The majority of Republicans took the position that Catholicism was the number one enemy of individualistic middle-class radicalism and must be completely broken as a source of influence in Portugal."[126] Under the leadership of Afonso Costa, the justice minister, the revolution immediately targeted the Catholic Church: churches were plundered, convents were attacked and clergy were harassed. Scarcely had the provisional government been installed when it began devoting its entire attention to an anti-religious policy, in spite of the disastrous economic situation. On 10 October—five days after the inauguration of the Republic—the new government decreed that all convents, monasteries and religious orders were to be suppressed. All residents of religious institutions were expelled and their goods confiscated. The Jesuits were forced to forfeit their Portuguese citizenship.

A series of anti-Catholic laws and decrees followed each other in rapid succession. On 3 November, a law legalizing divorce was passed and then there were laws to recognize the legitimacy of children born outside wedlock, authorize cremation, secularize cemeteries, suppress religious teaching in the schools and prohibit the wearing of the cassock. In addition, the ringing of church bells to signal times of worship was subjected to certain restraints, and the public celebration of religious feasts was suppressed. The government also interfered in the running of seminaries, reserving the right to appoint professors and determine curricula. This whole series of laws authored by Afonso Costa culminated in the law of Separation of Church and State, which was passed on 20 April 1911.

Constitution

A republican constitution was approved in 1911, inaugurating a parliamentary regime with reduced presidential powers and two chambers of parliament.[127] The Republic provoked important fractures within Portuguese society, notably among the essentially monarchist rural population, in the trade unions, and in the Church. Even the PRP had to endure the secession of its more moderate elements, who formed conservative republican parties like the Evolutionist Party and the Republican Union. In spite of these splits, the PRP, led by Afonso Costa, preserved its dominance, largely due to a brand of clientelist politics inherited from the monarchy.[128] In view of these tactics, a number of opposition forces were forced to resort to violence in order to enjoy the fruits of power. There are few recent studies of this period of the Republic's existence, known as the 'old' Republic. Nevertheless, an essay by Vasco Pulido Valente should be consulted (1997a), as should the attempt to establish the political, social, and economic context made by M. Villaverde Cabral (1988).

The PRP viewed the outbreak of the First World War as a unique opportunity to achieve a number of goals: putting an end to the twin threats of a Spanish invasion of Portugal and of foreign occupation of the African colonies and, at the internal level, creating a national consensus around the regime and even around the party.[129] These domestic objectives were not met, since participation in the conflict was not the subject of a national consensus and since it did not therefore serve to mobilise the population. Quite the opposite occurred: existing lines of political and ideological fracture were deepened by Portugal's intervention in the First World War.[130] The lack of consensus around Portugal's intervention in turn made possible the appearance of two dictatorships, led by General Pimenta de Castro (January–May 1915) and Sidónio Pais (December 1917 – December 1918).

Sidonismo, also known as Dezembrismo ("Decemberism"), aroused a strong interest among historians, largely as a result of the elements of modernity that it contained.[131][132][133][134][135][136] António José Telo has made clear the way in which this regime predated some of the political solutions invented by the totalitarian and fascist dictatorships of the 1920s and 1930s.[137] Sidónio Pais undertook the rescue of traditional values, notably the Pátria ("Homeland"), and attempted to rule in a charismatic fashion.

A move was made to abolish traditional political parties and to alter the existing mode of national representation in parliament (which, it was claimed, exacerbated divisions within the Pátria) through the creation of a corporative Senate, the founding of a single-party (the National Republican Party), and the attribution of a mobilising function to the leader. The state carved out an economically interventionist role for itself while, at the same time, repressing working-class movements and leftist republicans. Sidónio Pais also attempted to restore public order and to overcome some of the rifts of the recent past, making the republic more acceptable to monarchists and Catholics.

Political instability

The vacuum of power created by Sidónio Pais's murder[138] on 14 December 1918 led the country to a brief civil war. The monarchy's restoration was proclaimed in the north of Portugal (known as the Monarchy of the North) on 19 January 1919, and four days later a monarchist insurrection broke out in Lisbon. A republican coalition government, led by José Relvas, coordinated the struggle against the monarchists by loyal army units and armed civilians. After a series of clashes the monarchists were definitively chased from Oporto on 13 February 1919. This military victory allowed the PRP to return to government and to emerge triumphant from the elections held later that year, having won the usual absolute majority.

It was during this restoration of the 'old' republic that an attempted reform was carried out in order to provide the regime with greater stability. In August 1919 a conservative president was elected – António José de Almeida (whose Evolutionist party had come together in wartime with the PRP to form a flawed, because incomplete, Sacred Union) – and his office was given the power to dissolve parliament. Relations with the Holy See, restored by Sidónio Pais, were preserved. The president used his new power to resolve a crisis of government in May 1921, naming a Liberal government (the Liberal party being the result of the postwar fusion of Evolutionists and Unionists) to prepare the forthcoming elections.

These were held on 10 July 1921, with victory going, as was usually the case, to the party in power. However, Liberal government did not last long. On 19 October a military pronunciamento was carried out during which – and apparently against the wishes of the coup's leaders – a number of prominent conservative figures, including Prime Minister António Granjo, were assassinated. This event, known as the 'night of blood'[139] left a deep wound among political elites and public opinion. There could be no greater demonstration of the essential fragility of the Republic's institutions and proof that the regime was democratic in name only, since it did not even admit the possibility of the rotation in power characteristic of the elitist regimes of the nineteenth century.

A new round of elections on 29 January 1922 inaugurated a fresh period of stability: the PRP once again emerged from the contest with an absolute majority. Discontent with this situation had not, however, disappeared. Numerous accusations of corruption, and the manifest failure to resolve pressing social concerns wore down the more visible PRP leaders while making the opposition's attacks more deadly. At the same time, moreover, all political parties suffered from growing internal factionalism, especially the PRP itself. The party system was fractured and discredited.[128][140]

This is clearly shown by the fact that regular PRP victories at the ballot box did not lead to stable government. Between 1910 and 1926, there were forty-five governments. The opposition of presidents to single-party governments, internal dissent within the PRP, the party's almost non-existent internal discipline, and its desire to group together and lead all republican forces made any government's task practically impossible. Many different formulas were attempted, including single-party governments, coalitions, and presidential executives, but none succeeded. Force was clearly the sole means open to the opposition if the PRP wanted to enjoy the fruits of power.[141][142]

Evaluation of the republican experiment

Historians have emphasized the failure and collapse of the republican dream by the 1920s. Sardica summarizes the consensus of historians:

- within a few years, large parts of the key economic forces, intellectuals, opinion-makers and middle classes changed from left to right, trading the unfulfilled utopia of a developing and civic republicanism for notions of "order," "stability" and "security". For many who had helped, supported or simply cheered the Republic in 1910, hoping that the new political situation would repair the monarchy's flaws (government instability, financial crisis, economic backwardness and civic anomie), the conclusion to be drawn, in the 1920s, was that the remedy for national maladies called for much more than the simple removal of the king....The First Republic collapsed and died as a result of the confrontation between raised hopes and meager deeds.[143]

Sardica, however, also points out the permanent impact of the republican experiment:

- Despite its overall failure, the First Republic endowed twentieth-century Portugal with an insurpassable and enduring legacy—a renewed civil law, the basis for an educational revolution, the principle of separation between State and Church, the overseas empire (only brought to an end in 1975), and a strong symbolic culture whose materializations (the national flag, the national anthem and the naming of streets) nobody has dared to alter and which still define the present-day collective identity of the Portuguese. The Republic's prime legacy was indeed that of memory.[144]

28 May 1926 coup d'état

By the mid-1920s the domestic and international scenes began to favour another authoritarian solution, wherein a strengthened executive might restore political and social order. Since the opposition's constitutional route to power was blocked by the various means deployed by the PRP to protect itself, it turned to the army for support. The political awareness of the armed forces had grown during the war, and many of their leaders had not forgiven the PRP for sending them to a war they did not want to fight.[145]

They seemed to represent, to conservative forces, the last bastion of 'order' against the 'chaos' that was taking over the country. Links were established between conservative figures and military officers, who added their own political and corporative demands to the already complex equation. The 28 May 1926 coup d'état enjoyed the support of most army units and even of most political parties. As had been the case in December 1917, the population of Lisbon did not rise to defend the Republic, leaving it at the mercy of the army.[145]