| Prambanan | |

|---|---|

Prambanan Temple Compounds | |

| Location | Bokoharjo, Prambanan, Sleman Regency, Special Region of Yogyakarta & Prambanan, Klaten Regency, Central Java, Indonesia |

| Coordinates | 7°45′8″S 110°29′30″E / 7.75222°S 110.49167°E |

| Built | Originally built in 850 CE during the reign of the Hindu Sanjaya dynasty |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, iv |

| Designated | 1991 (15th session) |

| Part of | Prambanan Temple Compounds |

| Reference no. | 642 |

| Region | Southeast Asia |

Location within Java  Prambanan (Indonesia) | |

Prambanan (Indonesian: Candi Prambanan, Javanese: ꦫꦫꦗꦺꦴꦁꦒꦿꦁ, romanized: Rara Jonggrang) is a 9th-century Hindu

| Candi Prambanan | |

|---|---|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

temple compound in the Special Region of Yogyakarta, in southern Java, Indonesia, dedicated to the Trimūrti, the expression of God as the Creator (Brahma), the Preserver (Vishnu) and the Destroyer (Shiva). The temple compound is located approximately 17 kilometres (11 mi) northeast of the city of Yogyakarta on the boundary between Central Java and Yogyakarta provinces.[1]

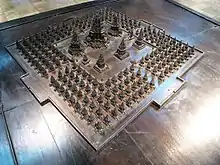

The temple compound, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the largest Hindu temple site in Indonesia and the second-largest in Southeast Asia after Angkor Wat.[1] It is characterized by its tall and pointed architecture, typical of Hindu architecture, and by the towering 47-metre-high (154 ft) central building inside a large complex of individual temples.[2] Prambanan temple compounds originally consisted of 240 temple structures, which represented the grandeur of ancient Java's Hindu art and architecture, and is also considered as a masterpiece of the classical period in Indonesia.[1] Prambanan attracts many visitors from around the world.[3][4]

History

Construction

The Prambanan temple is the largest Hindu temple of ancient Java, and the first building was completed in the mid-9th century. It was likely started by Rakai Pikatan and inaugurated by his successor King Lokapala. Some historians that adhere to dual dynasty theory suggest that the construction of Prambanan probably was meant as the Hindu Sanjaya dynasty's answer to the Buddhist Sailendra dynasty's Borobudur and Sewu temples nearby, and was meant to mark the return of the Hindu Sanjaya dynasty to power in Central Java after almost a century of Buddhist Sailendra dynasty domination. Nevertheless, the construction of this massive Hindu temple signified a shift of the Mataram court's patronage, from Mahayana Buddhism to Shaivite Hinduism.

A temple was first built at the site around 850 CE by Rakai Pikatan and expanded extensively by King Lokapala and Balitung Maha Sambu the Sanjaya king of the Mataram Kingdom. A short red-paint script bearing the name "pikatan" was found on one of the finials on top of the balustrade of Shiva temple, which confirms that King Pikatan was responsible for the initiation of the temple construction.[5]: 22

The temple complex is linked to the Shivagrha inscription of 856 CE, issued by King Lokapala, which described a Shiva temple compound that resembles Prambanan. According to this inscription the Shiva temple was inaugurated on 12 November 856.[5]: 20 According to this inscription, the temple was built to honor Lord Shiva, and its original name was Shiva-grha (the House of Shiva) or Shiva-laya (the Realm of Shiva).[6]

According to the Shivagrha inscription, a public water project to change the course of a river near Shivagrha temple was undertaken during the construction of the temple. The river, identified as the Opak River, now runs north to south on the western side of the Prambanan temple compound. Historians suggest that originally the river was curved further to east and was deemed too near to the main temple. Experts suggest that the shift of the river was meant to secure the temple complex from the overflowing of lahar volcanic materials from Merapi volcano.[7] The project was done by cutting the river along a north to south axis along the outer wall of the Shivagrha Temple compound. The former river course was filled in and made level to create a wider space for the temple expansion, the space for rows of pervara (ancillary) temples.

Some archaeologists propose that the statue of Shiva in the garbhagriha (central chamber) of the main temple was modelled after King Balitung, serving as a depiction of his deified self after death.[8] The temple compound was expanded by successive Mataram kings, such as Daksa and Tulodong, with the addition of hundreds of pervara temples around the chief temple.

With main prasada tower soaring up to 47 metres high, a vast walled temple complex consists of 240 structures, Shivagrha Trimurti temple was the tallest and the grandest of its time.[1] Indeed, the temple complex is the largest Hindu temple in ancient Java, with no other Javanese temples ever surpassed its scale. Prambanan served as the royal temple of the Kingdom of Mataram, with most of the state's religious ceremonies and sacrifices being conducted there. At the height of the kingdom, scholars estimate that hundreds of brahmins with their disciples lived within the outer wall of the temple compound. The urban center and the court of Mataram were located nearby, somewhere in the Prambanan Plain.

Abandonment

After being used and expanded for about 80 years, the temples were mysteriously abandoned near the half of the 10th century. In the 930s, the Javanese court was shifted to East Java by Mpu Sindok, who established the Isyana dynasty. It was not clear however, the true reason behind the abandonment of Central Java realm by this Javanese Mataram kingdom. The devastating 1006 eruption of Mount Merapi volcano located around 25 kilometres north of Prambanan in Central Java, or a power struggle may have caused the shift. That event marked the beginning of the decline of the temple, as it was soon abandoned and began to deteriorate.

The temples collapsed during a major earthquake in the 16th century. Although the temple ceased to be an important center of worship, the ruins scattered around the area were still recognizable and known to the local Javanese people in later times. The statues and the ruins became the theme and the inspiration for the Rara Jonggrang folktale.

The Javanese locals in the surrounding villages knew about the temple ruins before formal rediscovery, but they did not know about its historical background: which kingdoms ruled or which king commissioned the construction of the monuments. As a result, the locals developed tales and legends to explain the origin of temples, infused with myths of giants, and a cursed princess. They gave Prambanan and Sewu a wondrous origin; these were said in the Rara Jonggrang legend to have been created by a multitude of demons under the order of Bandung Bondowoso.

Rediscovery

In 1733, Cornelis Antonie Lons, a VOC employee, provided a first report on Prambanan temple in his journal. Lons was escorting Julius Frederick Coyett, a VOC commissioner of northeast Java coast, to Kartasura, then the capital of Mataram, a powerful local Javanese kingdom. During his sojourn in Central Java, he had the opportunity to visit the ruins of Prambanan temple, which he described as "Brahmin temples" that resembles a mountain of stones.[5]: 17

After the division of Mataram Sultanate in 1755, the temple ruins and the Opak River were used to demarcate the boundary between Yogyakarta and Surakarta Sultanates, which was adopted as the current border between Yogyakarta and the province of Central Java.

The temple attracted international attention early in the 19th century. In 1803, Nicolaus Engelhard, the Governor of the northeast coast of Java, made a stop in Prambanan during his official visits to two Javanese sultans: Pakubuwana IV of Surakarta and Hamengkubuwana II of Yogyakarta. Impressed by the temple ruins, in 1805 Engelhard commissioned H.C. Cornelius, an engineer stationed in Klaten, to clear the site from earth and vegetation, measuring the area, and made drawings of the temple. This was the first effort to study and restore Prambanan temple.[5]: 17

In 1811 during the short-lived British occupation of the Dutch East Indies, Colin Mackenzie, a surveyor in the service of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, came upon the temples by chance. Although Sir Thomas subsequently commissioned a full survey of the ruins, they remained neglected for decades. Dutch residents carried off sculptures as garden ornaments and native villagers used the foundation stones for construction material. Half-hearted excavations by archaeologists in the 1880s adversely facilitated looting instead, as numbers of temple sculptures were taken away as collections.

Reconstruction

In 1918, the Dutch colonial government began the reconstruction of the compound however proper restoration only commenced in 1930. Due to massive scale and the sheer numbers of temples, the efforts at restoration still continue up to this day. By 1930s, the reconstruction project by Dutch East Indies Archaeological Service successfully restored two apit (flank) temples in the central court, and two smaller pervara or in Indonesian: perwara (ancillary) temples. The reconstruction used the anastylosis method, in which a ruined temple is restored using the original stone blocks as much as possible.

The restoration efforts was hampered by the economic crisis in 1930s, and finally ceased altogether due to the outbreak of World War II Pacific War (1942-1945), and the following Indonesian National Revolution (1945-1949). After the war, the temple reconstruction resumed in 1949, despite much of technical drawings and photographs were damaged or lost during the war. The reconstruction of the main Shiva temple was completed in 1953 and inaugurated by Indonesia's first president Sukarno.

The Indonesian government continued the reconstruction effort to complete the temple compound. The Brahma temple was reconstructed between 1978 and 1987. While the Vishnu temple was rebuilt from 1982 to 1991.[5]: 28 The Vahana temples of the eastern rows and some smaller shrines were completed from 1991 to 1993. Thus by 1993, the whole towering main temples of the Prambanan central zone were erected and completed, simultaneously inaugurated by President Suharto together with the inauguration of the Sewu compound central temple nearby.[9]

Since much of the original stonework has been stolen and reused at remote construction sites, restoration was hampered considerably. Given the scale of the temple complex, the government decided to rebuild shrines only if at least 75% of their original masonry was available, in accordance to anastylosis discipline. The reconstruction continues up to this day, with efforts now focused on the pervara (ancillary) temples of the outer compound. A Pervara temple of eastern side second row number 35 was completed in December 2017.[10]

As per February 2023, from originally 224 pervara temples, only 6 of them are completely reconstructed; 4 on the eastern side, 1 on the southern side, and 1 on the northern side. Two of pervara temples; a corner pervara temple with double porticos on the northeast corner and a pervara temple on the east side, was reconstructed during the Dutch East Indies colonial era circa 1930s. The other 4 pervara temples were completed in 2015, 2017, 2019 and 2021 respectively. Most of the smaller shrines are now visible only in their foundations. The restoration of pervara temples will be carried out in stages. If all of 224 pervara temples to be restored completely, it will take at least 200 years, since an anastylosis reconstruction of one pervara temple takes approximately 8 to 12 months to complete.[11]

In the early 1990s the government removed the market that had sprung up near the temple and redeveloped the surrounding villages and rice paddies as an archaeological park. The park covers a large area, from Yogyakarta-Solo main road in the south, encompassing the whole Prambanan complex, the ruins of Lumbung and Bubrah temples, and as far as the Sewu temple compound in the north. In 1992 the Indonesian government created a State-owned Limited Liability Enterprise (Persero), named "PT Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur, Prambanan, dan Ratu Boko." This enterprise is the authority for the park management of Borobudur Prambanan Ratu Boko and the surrounding region. Prambanan is one of the most visited tourist attraction in Indonesia.

The Trimurti open-air and indoor stages on the west side of the temple, across the Opak River, were built to stage the ballet of the traditional Ramayana epic. This traditional Javanese dance is the centuries-old dance of the Javanese court. Since the 1960s, it has been performed every full moon night in the Prambanan temple. Since then, Prambanan has become one of the major archaeological and cultural tourism attractions in Indonesia.

Contemporary events

Since the reconstruction of the main temples in the 1990s, Prambanan has been reclaimed as an important religious center for Hindu rituals and ceremonies in Java. Balinese and Javanese Hindu communities in Yogyakarta and Central Java revived their practices of annually performing their sacred ceremonies in Prambanan, such as Galungan, Tawur Kesanga, and Nyepi.[12] "Nyepi di Candi Prambanan". Archived from the original on 2023-07-02. Retrieved 2010-01-20.</ref>

The temple was damaged during the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake. Early photos suggested that although the complex was structurally intact, the damage was significant. Large pieces of debris, including carvings, were scattered over the ground. The temple was closed to visitors until the damage could be fully assessed. Eventually, the head of Yogyakarta Archaeological Conservation Agency stated that it would take months to identify the full extent of the damage.[13][14] Some weeks later in 2006, the site was re-opened for visitors.

There is great interest in the site. In 2008, 856,029 Indonesian visitors and 114,951 foreign visitors visited Prambanan. On 6 January 2009 the reconstruction of Nandi temple finished.[15] As of 2009, the interior of most of the temples remains off-limits for safety reasons.

On 14 February 2014, major tourist attractions in Yogyakarta and Central Java, including Borobudur, Prambanan, and Ratu Boko, were closed to visitors after being severely affected by the volcanic ash from the eruption of Kelud volcano in East Java, located about 200 kilometers east of Yogyakarta. The Kelud volcano erupted on 13 February 2014 with explosions heard as far away as Yogyakarta.[16] Four years earlier, Prambanan was spared from the 2010 Merapi volcanic ash and eruption since the wind and ashfall were directed westward and affected Borobudur instead.

In 2012, the Balai Pelestarian Peninggalan Purbakala Jawa Tengah (BP3) or Central Java Heritage Preservation Authority suggested that the area in and around Prambanan should be treated as a sanctuary area. The proposed area is located in Prambanan Plain measured 30 square kilometers spanned across Sleman and Klaten Regency, which includes major temples in the area such as Prambanan, Ratu Boko, Kalasan, Sari and Plaosan temples. The sanctuary area is planned to be treated in a similar fashion to the Angkor archaeological area in Cambodia, which means the government should stop or decline permits to construct any new buildings, especially multi-storied buildings, as well as BTS towers in the area. This is meant to protect this archaeologically rich area from modern day visual obstructions and the encroachments of hotels, restaurants, and any tourism-related buildings and businesses.[17]

On 9 to 12 November 2019, the grand Abhiṣeka sacred ceremony was performed in this temple compound. This Hindu ritual was held for the first time after 1,163 years after the Prambanan temple was founded on 856.[18] The Abhiṣeka ceremony was meant to cleanse, sanctify and purify the temple, thus signify that the temple is not merely an archaeological and tourism site, but also restored to its original function as a focus of Hindu religious activity.[19] Indonesian Hindus believe that this Abhiṣeka ceremony marked a turning point to re-consecrated the temple ground and restore the spiritual energy of Prambanan temple.[20]

The temple compound

- This information does not take account of damage caused by the 2006 Yogyakarta earthquake

._-_Schaal_1250%252C_KITLV_51Z9.tif.jpg.webp)

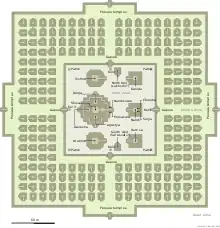

Originally there were a total of 240 temples standing in Prambanan. The Prambanan Temple Compound consist of:

- 3 Trimurti temples: three main temples dedicated to Shiva, Vishnu and Brahma

- 3 Vahana temples: three temples in front of Trimurti temples dedicated to the vahana of each gods; Nandi, Garuda and Hamsa

- 2 Apit temples: two temples located between the rows of Trimurti and Vahana temples on north and south side

- 4 Kelir temples: four small shrines located on 4 cardinal directions right beyond the 4 main gates of inner zone

- 4 Patok temples: four small shrines located on 4 corners of inner zone

- 224 Pervara temples: hundreds of temples arranged in 4 concentric square rows; numbers of temples from inner row to outer row are: 44, 52, 60, and 68

The Prambanan compound also known as Rara Jonggrang complex, named after the popular legend of Rara Jonggrang. There were once 240 temples standing in this Shivaite temple complex, either big or small.[21]: 8 Today, all of 8 main temples and 8 small shrines in the inner zone are reconstructed, but only 6 out of the original 224 pervara temples are renovated. The majority of them have deteriorated; what is left are only scattered stones. The Prambanan temple complex consists of three zones; first the outer zone, second the middle zone that contains hundreds of small temples, and third the holiest inner zone that contains eight main temples and eight small shrines.

The Hindu temple complex at Prambanan is based on a square plan that contains a total of three zone yards, each of which is surrounded by four walls pierced by four large gates. The outer zone is a large space marked by a rectangular wall. The outermost walled perimeter, which originally measured about 390 metres per side, was oriented in the northeast–southwest direction. However, except for its southern gate, not much else of this enclosure has survived down to the present. The original function is unknown; possibilities are that it was a sacred park, or priests' boarding school (ashram). The supporting buildings for the temple complex were made from organic material; as a consequence no remains occur.

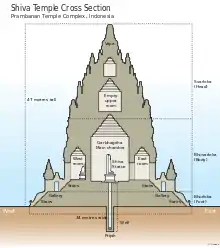

Shiva temple

The inner zone or central compound is the holiest among the three zones. It is the square elevated platform surrounded by a square stone wall with stone gates on each four cardinal points. This holiest compound is assembled of eight main shrines or candi. The three main shrines, called Trimurti ("three forms"), are dedicated to the three Gods: Brahma the Creator, Vishnu the Keeper, and Shiva the Destroyer.

The Shiva temple is the tallest and largest structure in Prambanan Rara Jonggrang complex; it measures 47 metres tall and 34 metres wide. The main stairs are located on the eastern side. The eastern gate of Shiva temple is flanked by two small shrines, dedicated to guardian gods, Mahakala and Nandhisvara. The Shiva temple is encircled with galleries adorned with bas-reliefs telling the story of Ramayana carved on the inner walls of the balustrades. To follow the story accurately, visitors must enter from the east side and began to perform pradakshina or circumambulating clockwise. The bas-reliefs of Ramayana continue to the Brahma temple galleries.

The Shiva shrine is located at the center and contains five chambers, four small chambers in every cardinal direction and one bigger main chamber in the central part of the temple. The east chamber connects to the central chamber that houses the largest murti in Prambanan, a three-metre high statue of Shiva Mahadeva (the Supreme God). The statue bears Lakçana (attributes or symbol) of Shiva such as skull and sickle (crescent) at the crown, and third eye on the forehead; also four hands that holds Shiva's symbols: aksamala (prayer beads), chamara (fly-whisk), and trisula (trident). Some historians believe that the depiction of Shiva as Mahadeva was also meant to personify king Balitung as the reincarnation of Shiva. So, when he died, a temple was built to commemorate him as Shiva.[21]: 11–12 The statue of Shiva stands on a lotus pad on a Yoni pedestal that bears the carving of Nāga serpents on the north side of the pedestal.

The other three smaller chambers contain statues of Hindu Gods related to Shiva: his consort Durga, the rishi Agastya, and Ganesha, his son. A statue of Agastya occupies the south chamber, the west chamber houses the statue of Ganesha, while the north chamber contains the statue of Durga Mahisasuramardini depicting Durga as the slayer of the Bull demon. The shrine of Durga is also called the temple of Rara Jonggrang (Javanese: slender virgin), after a Javanese legend of princess Rara Jonggrang.

Brahma and Vishnu temples

The two other main shrines are those of Vishnu on the north side of the Shiva shrine, and the one of Brahma on the south. Both temples face east and each contain only one large chamber, each dedicated to respected gods; Brahma temple contains the statue of Brahma and Vishnu temple houses the statue of Vishnu. Brahma and Vishnu temple measures 20 metres wide and 33 metres tall.

Vahana temples

The other three shrines in front of the three main temples are dedicated to the vehicles (vahana) of the respective gods – the bull Nandi for Shiva, the sacred swan Hamsa for Brahma, and Vishnu's kite Garuda. Precisely in front of the Shiva temple is the Nandi temple, which contains a statue of the Nandi bull. Next to it, there are also other statues, the statue of Chandra the god of the moon and Surya the god of the sun. Chandra stands on his carriage pulled by 10 horses, the statue of Surya also stands on a carriage pulled by 7 horses.[21]: 26 Facing the Brahma temple is the temple of Hamsa or Angsa. The chamber of this temple contains no statue, but it seems likely that there was once a statue of the sacred swan. In front of the Vishnu temple is the temple dedicated to Garuda. However, just like the Hamsa temple, the Garuda temple contains no statue, but probably once contained the statue of Garuda. Garuda holds an important role for Indonesia, as it serves as the national symbol of Indonesia, and also as the name of the airline Garuda Indonesia.

Apit temples and smaller shrines

Between these rows of the main temple, on the north and south side, stand two Candi Apit temples. Apit in Javanese means "flank". It refers to the position of the two temples that flanked the inner courtyard on the north and south sides. The room inside the Apit temples is now empty. It is not clear to which deities these Apit temples were dedicated. However, examining the southern Apit temple bas-reliefs on the outer wall, a female deity is depicted, most probably Sarasvati, the Shakti (consort) of Brahma. Considering the Hindu pantheon represented in Prambanan temples, it is possible that the southern Apit temple was dedicated to Sarasvati, while the northern Apit temple was dedicated to Lakshmi.

Beside these 8 main temples, there are also 8 smaller shrines; 4 Candi Kelir on four cardinal directions of the entrance, and 4 Candi Patok on four corners of the inner zone. Kelir in Javanese means "screen", especially referring to wayang kulit, fabric screen. It refers to a structure that obstructs the main cardinal entry of gopura. It is similar to aling-aling in Balinese architecture. Patok in Javanese means "peg". It refers to the shrine location at the four corners of the inner compound.

Pervara temples

The two walled perimeters that surround the remaining two yards to the interior are oriented to the four cardinal points. The second yard's walled perimeter, which measures about 225 metres per side, surrounds a terraced area that consists of four rows containing 44, 52, 60, and 68 pervara temples, for 224 structures in total. Respectively, each has a height of 14 metres and measures 6×6 metres at the base. The sixteen temples located at the corners of the rows face two directions; the remaining 208 structures open to only one of the four cardinal directions.[22]

The middle zone consists of four rows of 224 individual small shrines. There are great numbers of these temples, but most of them are still in ruins and only some have been reconstructed. These concentric rows of temples were made in an identical design, with flight of stairs and porticos facing outward, with exception of the corner pervara temples that has two porticos. Each row towards the center is slightly elevated.

These shrines are called "Candi Perwara" in Indonesian or pervara temples, which means ancillary, guardian or complementary temples, the additional buildings of the main temple. Some believed it was offered by regional rulers and nobles to the king as a sign of submission. The pervara are arranged in four rows around the central temples. Some believed it had something to do with four castes, made according to the rank of the people allowed to enter them; the row nearest to the central compound was accessible to the priests only, the other three were reserved for the nobles, the knights, and the simple people respectively. While another believed that the four rows of pervara had nothing to do with four castes, it was just simply made as a meditation place for priests and as a worship place for devotees.

Gates and walls

Most of the original perimeter walls and gapura gates surrounding the outer compound are missing, leaving only the trace of wall's foundations. The walls and gates demarcating the middle compound that contains rows of pervara temples are mostly gone too, with exception of the southern gate that has been successfully reconstructed.

The paduraksa gates into inner compound are mostly has been completely reconstructed; i.e. south, west, and north paduraksa gates, with the exception only eastern gate that has not been rebuilt yet.

Architecture

The architecture of the Prambanan temple follows the typical Hindu architecture traditions based on Vastu Shastra. The temple design incorporated mandala temple plan arrangements and also the typical high towering spires of Hindu temples. Prambanan was originally named Shivagrha and dedicated to the god Shiva. The temple was designed to mimic Meru, the holy mountain, the abode of Hindu gods, and the home of Shiva. The whole temple complex is a model of the Hindu universe according to Hindu cosmology and the layers of Loka.

Just like Borobudur, Prambanan also recognizes the hierarchy of the temple zones, spanned from the less holy to the holiest realms. Each Hindu and Buddhist concept has its terms, but the concepts are essentially identical. Either the compound site plan (horizontally) or the temple structure (vertically) consists of three zones:[23]

- Bhurloka (in Buddhism: Kāmadhātu), the lowest realm of common mortals; humans, animals also demons. Where humans are still bound by their lust, desire and unholy way of life. The outer courtyard and the foot (base) part of each temple has symbolized the realm of bhurloka.

- Bhuvarloka (in Buddhism: Rupadhatu), the middle realm of holy people, occupied by rishis, ascetics, and lesser gods. People here begin to see the light of truth. The middle courtyard and the body of each temple symbolize the realm of bhuvarloka.

- Svarloka (in Buddhism: Arupadhatu), the highest and holiest realm, reserved for the gods. Also known as svargaloka. The inner courtyard and the roof of each temple symbolize the realm of svarloka. The roof of Prambanan temples are adorned and crowned with ratna (sanskrit: jewel), the shape of Prambanan Ratna took the altered form of vajra that represent diamonds. In ancient Java temple architecture, Ratna is the Hindu counterpart of the Buddhist stupa, and served as the temple's pinnacle. It also has more than 140 inner temples, along with 30 main ones.

During the restoration, a well which contains a pripih (stone casket) was discovered under the centre of the Shiva temple. The main temple has a well 5.75 m deep in which a stone casket was found on top a pile of charcoal, earth, and remains of burned animal bones. Sheets of gold leaves with the inscription Varuna (god of the sea) and Parvata (god of the mountains) were found here. The stone casket contained sheets of copper, charcoal, ashes, earth, 20 coins, jewels, glass, pieces of gold and silver leaves, seashells and 12 gold leaves (which were cut in the shapes of a turtle, Nāga serpent, padma, altar, and an egg).[24]

Reliefs

Ramayana and Bhagavata Purana

The temple is adorned with panels of narrative bas-reliefs telling the story of the Hindu epic Ramayana and Bhagavata Purana. The narrative bas-relief panels were carved along the inner balustrades wall on the gallery around the three main temples.

The narrative panels on the balustrade read from left to right. The story starts from the east entrance where visitors turn left and move around the temple gallery in a clockwise direction. This conforms with pradaksina, the ritual of circumambulation performed by pilgrims who move in a clockwise direction while keeping the sanctuary to their right. The story of Ramayana starts on Shiva temple balustrade and continues to Brahma temple. On the balustrades in Vishnu temple there is series of bas-relief panels depicting the stories of lord Krishna from Bhagavata Purana.

The bas-relief of Ramayana illustrate how Sita, the wife of Rama, is abducted by Ravana. The monkey king Hanuman brings his army to help Rama and rescue Sita. This story is also shown by the Ramayana Ballet, regularly performed at full moon at Trimurti open-air theatre on the west side of the illuminated Prambanan complex.

Lokapalas, Brahmins and Devatas

On the other side of the narrative panels, the temple wall along the gallery was adorned with statues and reliefs of devatas and brahmin sages. The figures of lokapalas, the celestial guardians of directions, can be found in Shiva temple. The brahmin sage editors of veda were carved on Brahma temple wall, while in Vishnu temple the figures of male deities devatas are flanked by two apsaras.

Prambanan panel: Lion and Kalpataru

The lower outer wall of these temples was adorned with a row of small niches containing an image of sinha (a lion) flanked by two panels depicting bountiful kalpataru (kalpavriksha) trees. These wish-fulfilling sacred trees, according to Hindu-Buddhist belief, are flanked on either side by kinnaras or animals, such as pairs of birds, deer, sheep, monkeys, horses, elephants etc. The pattern of lion in niche flanked by kalpataru trees is typical in the Prambanan temple compound, thus it is called a "Prambanan panel".

The Rara Jonggrang legend

The popular legend of Rara Jonggrang is what connects the site of the Ratu Boko Palace, the origin of the Durga statue in the northern cell/chamber of the main shrine, and the origin of the Sewu temple complex nearby. The legend tells the story about Prince Bandung Bondowoso, who fell in love with Princess Rara Jonggrang, the daughter of King Boko. But the princess rejected his proposal of marriage because Bandung Bondowoso had killed King Boko and ruled her kingdom. Bandung Bondowoso insisted on the union, and finally Rara Jonggrang was forced to agree to a union in marriage, but she posed one impossible condition: Bandung must build her a thousand temples in only one night.

The Prince entered into meditation and conjured up a multitude of supernatural beings from the earth. Helped by these spirits, he succeeded in building 999 temples. When the prince was about to complete the condition, the princess woke her palace maids and ordered the women of the village to begin pounding rice and set a fire in the east of the temple, attempting to make the prince and the spirits believe that the sun was about to rise. As the cocks began to crow, fooled by the light and the sounds of daybreak, the supernatural helpers fled back into the ground. The prince was furious about the trick and in revenge he cursed Rara Jonggrang, turning her to stone. She became the last and the most beautiful of the thousand statues. According to the traditions, the unfinished thousandth temple created by the demons become the Sewu temple compounds nearby (Sewu means "thousands" in Javanese), and the Princess is the image of Durga in the north cell of the Shiva temple at Prambanan, which is still known as Rara Jonggrang or "Slender Maiden".

Access

The Prambanan temple compound, as well as the entire archaeological complex, is easily accessible because its proximity with Yogyakarta–Solo highway, a highway running from Yogyakarta in the west to Surakarta, Central Java in the east. The highway, located south of the complex, is a part of Indonesian National Route 15, which running from Yogyakarta further into Surabaya in East Java.

The temple compound is also close to Prambanan bus terminal, in which the K3S line of Trans Jogja stops there as a terminal point. About 750 meters southeast from the compound is Brambanan Station in Klaten Regency, which serves KAI Commuter's Yogyakarta Line.

Other temples around Prambanan

The Prambanan Plain spans between the southern slopes of Merapi volcano in the north and the Sewu mountain range in the south, near the present border Yogyakarta province and Klaten Regency, Central Java. Apart from the Lara Jonggrang complex, the Prambanan plain, valley and hills around it is the location of some of the earliest Buddhist temples in Indonesia. Not far to the north are found the ruins of Bubrah temple, Lumbung temple, and Sewu temple. Further east is found Plaosan temple. To the west are found Kalasan temple and Sari temple, and further to the west is Sambisari temple. While to the south the Ratu Boko compound is on higher ground. The discoveries of archaeological sites scattered only a few miles away suggest that this area was an important religious, political, and urban center.

North of the Lara Jongrang complex

- Lumbung. Buddhist-style, consisting of one main temple surrounded by 16 smaller ones.

- Bubrah. Buddhist temple, rebuilt between 2011 and 2017.[25]

- Sewu. Buddhist temple complex, older than Roro Jonggrang. A main sanctuary surrounded by many smaller temples. Well preserved guardian statues, replicas of which stand in the central courtyard at the Jogja Kraton.

- Morangan. Hindu temple complex buried several meters under volcanic ashes, located northwest from Prambanan.

- Plaosan. Buddhist, probably 9th century. Thought to have been built by a Hindu king for his Buddhist queen. Two main temples with exquisite reliefs of Boddhisatva and Tara. Also rows of slender stupas.

South of the Lara Jongrang complex

- Ratu Boko. Complex of fortified gates, bathing pools, and elevated walled stone enclosure, all located on top of the hill.

- Sajiwan. Buddhist temple decorated with jataka bas reliefs concerning education. The base and staircase are decorated with animal fables.

- Banyunibo. A Buddhist temple with unique design of roof.

- Barong. A Hindu temple complex with large stepped stone courtyard. Located on the slope of the hill.

- Ijo. A cluster of Hindu temple located near the top of Ijo hill. The main temple houses a large lingam and yoni.

- Arca Bugisan. Seven Buddha and bodhisattva statues, some collapsed, representing different poses and expressions.

West of the Lara Jongrang complex

- Kalasan. 8th-century Buddhist temple dedicated to Boddhisattvadevi Tara. The oldest temple in Prambanan plain, ornamented with finely carved reliefs.

- Sari. Once a sanctuary for Buddhist priests. 8th century. Nine stupas at the top with two rooms beneath, each believed to be places for priests to meditate.

- Sambisari. 9th-century Hindu temple discovered in 1966, once buried 6.5 metres under volcanic ash. The main temple houses a linga and yoni, and the wall surround it displayed the images of Agastya, Durga, and Ganesha.

- Gebang. A small Hindu temple discovered in 1937 located near the Yogyakarta northern ring-road. The temple displays the statue of Ganesha and interesting carving of faces on the roof section.

- Gana. A temple ruin with numerous reliefs and sculpted stones. Frequent representations of gana dwarfs with raised hands. Located east from Sewu temple, in the middle of a housing complex. Under restoration since 1997.

- Kedulan. A Hindu temple discovered in 1994 by sand diggers, 4m deep. The architectural style is somewhat identical to Sambisari temple nearby.

Gallery

Gallery of reliefs

Gallery of Prambanan

The main temple dedicated of Shiva

The main temple dedicated of Shiva Temple of Vishnu

Temple of Vishnu.jpg.webp) Temple of Brahma

Temple of Brahma Temple of Nandi

Temple of Nandi.jpg.webp) Brahma Statue

Brahma Statue.jpg.webp) Vishnu Statue

Vishnu Statue The Ganesha statue

The Ganesha statue Kinnara relief in Prambanan temple

Kinnara relief in Prambanan temple

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Prambanan Temple Compounds". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2020-01-14. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- ↑ "Prambanan Temple Complex". Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-08-12.

- ↑ "Prambanan Temple". indonesia-tourism.com. Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- ↑ "Prambanan - World Heritage Site - Pictures, Info and Travel Reports". www.worldheritagesite.org. Archived from the original on 2020-10-01. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tjahjono Prasodjo; Thomas M. Hunter; Véronique Degroot; Cecelia Levin; Alessandra Lopez y Royo; Inajati Adrisijanti; Timbul Haryono; Julianti Lakshmi Parani; Gunadi Kasnowihardjo; Helly Minarti (2013). Magical Prambanan. Yogyakarta: PT (Persero) Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur, Prambanan & Ratu Boko. ISBN 978-602-98279-1-0. Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- ↑ Shivagrha Inscription, National Museum of Indonesia

- ↑ Guna, Anwar Sadat (6 November 2011). "Alur Sungai Opak di Candi Prambanan Pernah Dibelokkan". Tribunnews.com (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 2021-03-04. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ↑ Soetarno, Drs. R. second edition (2002). Aneka Candi Kuno di Indonesia (Ancient Temples in Indonesia), pp. 16. Dahara Prize. Semarang. ISBN 979-501-098-0.

- ↑ "Kompleks Candi Prambanan". Balai Pelestarian Cagar Budaya D.I. Yogyakarta (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2020-12-25.

- ↑ Hanafi, Ristu (14 December 2017). "Mendikbud Resmikan Purnapugar Candi Perwara Prambanan". detiknews (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 2022-05-29. Retrieved 2020-12-25.

- ↑ Razak, Abdul Hamied (3 February 2023). "Pemugaran Candi Perwara Prambanan Bakal Tambah Daya Tarik Wisatawan". Harian Jogja (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 2023-02-20. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

- ↑ "Keindahan Sejarah dan Arsitektur yang Memukau". Archived from the original on 2024-01-06. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ↑ IOL (2006). "World famous temple complex damaged in quake". Archived from the original on 2012-05-25. Retrieved 2006-05-28.

- ↑ Di sản thế giới tại Indonesia bị động đất huỷ hoại Archived 2010-06-13 at the Wayback Machine (in Vietnamese)

- ↑ "Yogyakarta Online Candi Nandi Selesai Dipugar". Archived from the original on 2021-01-25. Retrieved 2011-09-07.

- ↑ "Borobudur, Other Sites, Closed After Mount Kelud Eruption". JakartaGlobe. February 14, 2014. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ "Prambanan Diusulkan Jadi "Perdikan"". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). 18 April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "Upacara Abhiseka di Candi Prambanan Yogyakarta by | The Jakarta Post Images". www.thejakartapostimages.com. Archived from the original on 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ↑ Kurnia, Fadjrin (5 November 2019). "Abhiseka Prambanan". bumn.go.id (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ↑ "Pertama Kali Sejak Tahun 856 Masehi, Umat Hindu Gelar Upacara Abhiseka di Candi Prambanan". Tribun Bali (in Indonesian). 13 November 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- 1 2 3 Ariswara (1993). Prambanan. Jakarta: Intermasa. ISBN 9798114574. Archived from the original on 2021-12-06. Retrieved 2020-12-24.

- ↑ "Prambanan: A Brief Architectural Summary". Borobudur TV. Archived from the original on 2003-05-09. Retrieved 2011-10-31.

- ↑ Konservasi Borobudur Archived 2011-07-26 at the Wayback Machine (in Indonesian)

- ↑ "Candi Lara Jonggrang". Archived from the original on 2011-02-09. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ↑ "Candi Bubrah Kini Cantik, Rehab 4 Tahun Habis Rp 13,13 M". Tribun Jogja (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 2019-04-19. Retrieved 2019-04-19.

Bibliography

- Tjahjono Prasodjo; Thomas M. Hunter; Véronique Degroot; Cecelia Levin; Alessandra Lopez y Royo; Inajati Adrisijanti; Timbul Haryono; Julianti Lakshmi Parani; Gunadi Kasnowihardjo; Helly Minarti (2013). Magical Prambanan. Yogyakarta: PT (Persero) Taman Wisata Candi Borobudur, Prambanan & Ratu Boko. ISBN 978-602-98279-1-0.

- Ariswara, third edition (1993) (English translation by Lenah Matius) Prambanan, Intermasa, Jakarta, ISBN 979-8114-57-4

- Bernet Kempers, A.J. (1959) Ancient Indonesian art Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press.

- Dumarcay, Jacques. (1989) (Edited and translated by Michael Smithies) The temples of Java, Singapore: Oxford University Press.

- Holt, Claire (1967) Art in Indonesia: Continuities and change Ithaca, N.Y. Cornell University Press.

- Jordaan, Roy https://web.archive.org/web/20120319200224/http://www.iias.nl/iiasn/iiasn6/southeas/jordaan.html Prambanan 1995: A Hypothesis Confirmed

- Kak, S. (2011) Space and order in Prambanan. In M. Gupta (ed.) From Beyond the Eastern Horizon: Essays in honour of Professor Lokesh Chandra. Aditya Prakashan, Delhi.

- Leemans, C. (1855) Javaansche tempels bij Prambanan BKI, vol.3. pp. 1–26

.jpg.webp)