Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus Αὐτόνομος Δημοκρατία τῆς Βορείου Ἠπείρου | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | |||||||||

Flag

Seal

| |||||||||

| Anthem: Ύμνος εις τὴν Ελευθερίαν "Hymn to Freedom" | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Independence under provisional, unrecognized status: 28 February – 17 May 1914 Autonomy under nominal (unimplemented) Albanian sovereignty: 17 May – 27 October 1914 | ||||||||

| Capital | Argyrokastron (Gjirokastër) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Official: Greek, Secondary: Albanian[1] | ||||||||

| Ethnic groups | Greeks Albanians Aromanians | ||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox Muslim | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Northern Epirot | ||||||||

| Government | Provisional | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1914 | Georgios Christakis-Zografos | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 28 February 1914 | |||||||||

| 17 May 1914 | |||||||||

• 2nd Greek Administration | 27 October 1914 | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• Estimate | 223,000 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Albania | ||||||||

The Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus (Greek: Αὐτόνομος Δημοκρατία τῆς Βορείου Ἠπείρου, romanized: Aftónomos Dimokratía tis Voreíou Ipeírou) was a short-lived, self-governing entity founded in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars on 28 February 1914, by the local Greek population in southern Albania (Northern Epirotes).[2]

The area, known as Northern Epirus to Greeks and with a substantial Greek population, was taken by the Greek Army from the Ottoman Empire during the First Balkan War (1912–1913). The Protocol of Florence, however, had assigned it to the newly established Albanian state. This decision was rejected by the local Greeks, and as the Greek Army withdrew to the new border, an autonomous government was set up at Argyrokastron (Greek: Αργυρόκαστρον, today Gjirokastër), under the leadership of Georgios Christakis-Zografos, a distinguished local Greek politician and former Minister of Foreign Affairs, and with tacit support from Greece.[3]

In May, the autonomy was confirmed by the Great Powers with the Protocol of Corfu. The agreement ensured that the region would have its own administration, recognized the rights of the local population and provided for self-government under nominal Albanian sovereignty. However, it was never fully implemented because in September the Albanian government collapsed. The Greek Army reoccupied the area in October 1914 following the outbreak of World War I. It was planned that Northern Epirus would be ceded to Greece following the war, but the withdrawal of Italian support and Greece's defeat in the Asia Minor Campaign resulted in its final cession to Albania in November 1921.[4]

Background

Northern Epirus and the Balkan Wars

In March 1913, during the First Balkan War, the Greek Army entered Ioannina after breaching the Ottoman fortifications at Bizani, and soon afterwards advanced further north.[5] Himarë had already been under Greek control since 5 November 1912, after a local Himariote, Gendarmerie Major Spyros Spyromilios, led a successful uprising that met no initial resistance.[6] By the end of the war, Greek armed forces controlled most of the historical region of Epirus, from the Ceraunian mountains along the Ionian coast to Lake Prespa in the east.[7]

At the same time, the Albanian independence movement gathered momentum. On 28 November 1912 in Vlorë, Ismail Qemali declared Albania's independence, and a provisional government was soon formed that exercised its authority only in the immediate area of Vlorë. Elsewhere, the Ottoman general Essad Pasha formed the Republic of Central Albania at Durrës,[8] while conservative Albanian tribesmen still hoped for an Ottoman ruler.[9] Most of the area that would form the Albanian state was occupied at this time, by the Greeks in the south and the Serbs in the north.[10]

The last Ottoman census, conducted in 1908, counted 128,000 Orthodox Christians and 95,000 Muslims in the region.[11] Moreover, they expressed a strong pro-Greek feeling, and were the first to support the following breakaway autonomist movement.[12] Considering these conditions, loyalty in Northern Epirus to an Albanian government competing in anarchy, whose leaders were mostly Muslim, could not be guaranteed.[13]

Delineation of the Greek–Albanian border

The concept of an independent Albanian state was supported by the Great European Powers, particularly Austro-Hungary and Italy.[14] Both powers were seeking to control Albania, which, in the words of Italian Foreign Minister Tommaso Tittoni, would give whichever managed this "incontestable supremacy in the Adriatic". The Serbian possession of Shkodër and the possibility of the Greek border running a few miles south of Vlore was therefore strongly resisted by these states.[10][15]

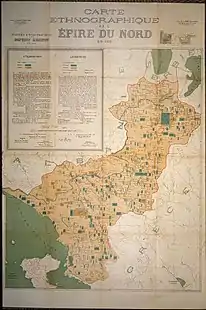

In September 1913, an International Commission of the European Powers convened to determine the boundary between Greece and Albania. The delegates of the commission aligned themselves into two camps: those of Italy and Austro-Hungary insisted that the Northern Epirus districts were Albanian, while those of the Triple Entente (the United Kingdom, France, and Russia) took the view that although the older generations in some villages spoke Albanian, the younger generation was Greek in intellectual outlook, sentiment, and aspirations.[16] Under Italian and Austro-Hungarian pressure, the commission determined that the region of Northern Epirus would be ceded to Albania.[17]

Treaty of London and Protocol of Florence

Though the Treaty of London, 1913, recognized the independence of the Albanian state its exact borders were to be laid down in the Protocol of Florence. On 21 February 1914, the ambassadors of the Great Powers delivered a note to the Greek government asking for the Greek army's evacuation of the area. Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos acceded to this in hopes of a favourable solution to Greece's other outstanding problem: the recognition of Greek sovereignty over the islands of the North Eastern Aegean.[18][19]

Reactions

Declaration of Independence

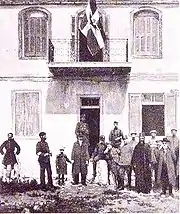

This turn of events was highly unpopular among the pro-Greek party in the area. The pro-Greek Epirotes felt betrayed by the Greek government, which had done nothing to support them with firearms. Additionally, the gradual withdrawal of the Greek army would enable Albanian forces to take control of the region. To avert this possibility, the Epirotes decided to declare their own separate political identity and self-governance.[20][21] Georgios Christakis-Zografos, a distinguished Epirote statesman from Lunxhëri (gr. Lioúntzi) and former Greek foreign minister, took the initiative and discussed the situation with local representatives in a "Panepirotic Council". Consequently, on 28 February 1914, the Autonomous[22] Republic of Northern Epirus was declared in Gjirokastër (gr. Argyrókastron) and a provisional government, with Christakis-Zografos as president, formed to support the state's objectives.[20] [23] In his speech on 2 March,[3] Christakis-Zografos stated that the aspirations of the Northern Epirotes had been totally ignored, and that the Great Powers had not only rejected their becoming autonomous within the Albanian state but also refused to give guarantees regarding their fundamental human rights.[20] Zografos concluded his speech by stating that the Northern Epirotes would not accept the destiny the Powers had imposed upon them:[24]

Because of this inalienable right of each people, the Great Powers' desire to create for Albania a valid and respected title of dominion over our land and to subjugate us is powerless before the fundamentals of divine and human justice. Neither does Greece have the right to continue in occupation of our territory merely to betray it against our will to a foreign tyrant.

Free of all ties, unable to live united under these conditions with Albania, Northern Epirus proclaims its independence and calls upon its citizens to undergo every sacrifice to defend the integrity of the territory and its liberties from any attack whatsoever.

The flag of the new state was a variant of the Greek national flag, consisting of a white cross centred upon the blue background surmounted by the imperial Byzantine eagle in black.[25]

In the following days, Alexandros Karapanos, Zografos' nephew and an MP for Arta,[26] was installed as foreign minister. Colonel Dimitrios Doulis, a local from Nivice, resigned from his post in the Greek army and joined the provisional government as minister of military affairs. Within a few days, he managed to mobilize an army consisting of more than 5,000 volunteer troops.[27] The local bishop, Vasileios of Dryinoupolis, took office as minister of Religion and Justice. A number of officers of Epirote origin (not exceeding 30), as well as ordinary soldiers, deserted their positions in the Greek Army and joined the revolutionaries. Soon, armed groups, such as the "Sacred Band" or Spyromilios' men around Himarë (gr. Himárra), were formed[26] in order to repel any incursion into the territory claimed by the autonomous government. The first districts to join the autonomist movement outside of Gjirokastër were Himarë, Sarandë and Përmet.[28]

Greece's reaction and evacuation

The Greek government was reluctant to overtly support the uprising. Military and political officials continued to carry out a slow evacuation process, which had begun in March and ended on 28 April.[26] Resistance was officially discouraged, and assurances were given that the Great Powers and the International Control Commission (an organization founded by the Great Powers in order to secure peace and stability in the area) would guarantee their rights. Following the declaration in Gjirokastër, Zografos sent messages to local representatives in Korçë (gr. Korytsá) asking them to join the movement; however, the Greek military commander of the city, Colonel Alexandros Kontoulis, followed his official orders strictly and declared martial law, threatening to shoot any citizen raising the Northern Epirote flag. When the local bishop of Kolonjë (gr. Kolónia), Spyridon, proclaimed the Autonomy, Kontoulis had him immediately arrested and expelled.[29]

On 1 March, Kontoulis ceded the region to the newly formed Albanian gendarmerie, consisting mainly of former deserters of the Ottoman army and under the command of Dutch and Austrian officers.[28] On 9 March, the Greek navy blockaded the port of Sarandë (gr. Ágioi Saránda, known also as Santi Quaranta), one of the first cities that had joined the autonomist movement.[30] There were also sporadic conflicts between Greek army and Epirote units, with a few casualties on both sides.[31]

Negotiations and armed conflicts

As the Greek army withdrew, armed conflicts broke out between Albanian and Northern Epirote forces. In the regions of Himarë, Sarandë, Gjirokastër and Delvinë (gr. Delvínion), the revolt had been in full force since the first days of the declaration, and the autonomist forces were able to successfully engage the Albanian gendarmerie, as well as Albanian irregular units.[29] However, Zografos, seeing that the Great Powers would not approve the annexation of Northern Epirus to Greece, suggested three possible diplomatic solutions:[28]

- full autonomy under the nominal sovereignty of the Albanian prince;

- an administrative and cantonal system autonomy; and

- direct control and administration by the European Powers.

On 7 March, Prince William of Wied arrived in Albania, and intense fighting occurred north of Gjirokastër, in the region of Cepo, in an attempt to take control over Northern Epirus; Albanian gendarmerie units tried unsuccessfully to infiltrate southwardly, facing resistance from the Epirotes.[26] On 11 March, a provisional settlement was brokered in Corfu by Dutch Colonel Thomson. Albania was prepared to accept a limited Northern Epirote government, but Karapanos insisted on complete autonomy, a condition rejected by the Albanian delegates, and negotiations reached a deadlock.[26][29] Meanwhile, Epirote bands entered Erseka and continued on to Frashër and Korçë.[32]

At this point, the entire region that had been claimed by the provisional government, with the exception of Korçë, was under its control. On 22 March, a Sacred Band unit from Bilisht reached the outskirts of Korçë and joined the local guerillas, and fierce street fighting took place. For several days, Northern Epirote units controlled the city, but on 27 March, this control was lost to the Albanian gendarmerie upon the arrival of Albanian reinforcements.[29]

The International Control Commission, in order to avoid a major escalation of the armed conflicts with disastrous results, decided to intervene. On 6 May, Zografos received a communication to initiate negotiations on a new basis. Zografos accepted the proposal and an armistice was ordered the next day. By the time the cease-fire order was received, the Epirote forces had secured the Morava heights near Korçë, making the city's Albanian garrison's surrender imminent.[33]

Recognition of autonomy and outbreak of World War I

Protocol of Corfu

Negotiations were carried out on the island of Corfu, where on 17 May 1914 Albanian and Epirote representatives signed an agreement known as the Protocol of Corfu. According to its terms, the two provinces of Korçë and Gjirokastër that constituted Northern Epirus would acquire complete autonomous existence (as a corpus separatum) under the nominal Albanian sovereignty of Prince Wied.[26][33] The Albanian government had the right to appoint and dismiss governors and upper-rank officials, taking into account as much as possible the opinion of the local population. Other terms included the proportional recruitment of natives into the local gendarmerie and the prohibition of military levies from people not indigenous to the region.[26] In Orthodox schools, the Greek language would be the sole medium of instruction, with the exception of the first three classes. The use of the Greek language was made equal to Albanian in all public affairs. The Ottoman-era privileges of Himarë were renewed, and a foreigner was to be appointed as its "captain" for 10 years.[34]

The execution of and adherence to the Protocol was entrusted to the International Control Commission, as was the organization of public administration and the departments of justice and finance in the region.[35] The creation and training of the local gendarmerie was to be conducted by Dutch officers.[36]

Territory: All the provisions in question shall apply to the populations of the territories previously occupied by Greece and annexed to Albania.

Armed Forces: Except in case of war or revolution, non-native military units shall not be transferred to or employed in these provinces.

Occupation: The International Control Commission (I.C.C.) will take possession in the territory in question, in the name of the Albanian Government, by proceeding to the place. The officers of the Dutch mission will at once begin the organization of the local gendarmerie...Before the arrival of the Dutch officers, the necessary steps will be taken by the Provisional Government of Argyrokastro for the removal of the country of all armed foreign elements. These provisions will not only be applied in that part of the provinces of Korytsa now occupied militarily by Albania, but in any other southern regions.

Liberty of language: The permission to use both Albanian and Greek shall be assured, before all authorities, including the Courts, as well as the elective councils.

Guarantee: The Powers who, by the Conference of London, have guaranteed the institution of Albania and established the I.C.C. guarantee the execution and maintenance of the foregoing provisions.— From the Protocol of Corfu, 17 May 1914[37]

The agreement of the Protocol was ratified by the representatives of the Great Powers at Athens on 18 June and by the Albanian government on 23 June.[38] The Epirote representatives, in an assembly in Delvinë, gave the final approval to the terms of the Protocol, although the delegates from Himara protested, claiming that union with Greece was the only viable solution.[39] On July 8, control of the cities of Tepelenë and Korçë passed to the provisional government of Northern Epirus.[26]

Instability and disestablishment

After the outbreak of World War I, the situation in Albania became unstable, and political chaos emerged as the country was split into a number of regional governments. As a consequence of the anarchy in central and northern Albania, sporadic armed conflicts continued to occur in spite of the Protocol of Corfu's ratification,[40] and on September 3 Prince Wilhelm departed the country. In the following days, an Epirote unit launched an attack on the Albanian garrison in Berat without approval from the provisional government, managing to capture its citadel for several days, while Albanian troops loyal to Essad Pasha initiated small-scale armed operations.[41]

These events worried Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos, as well as the possibility that the unstable situation could spill over outside Albania, triggering a wider conflict. On 27 October, after receiving the approval of the Great Powers,[42] the Greek Army's V Army Corps entered the area for a second time. The provisional government formally ceased to exist, declaring that it had accomplished its objectives.

Aftermath

Greek administration (October 1914 – September 1916)

During the Greek administration at the time of the First World War, it had been agreed to by Greece, Italy and the Great Powers that the final settlement of the Northern Epirote issue would be left for the post-war future. In August 1915, Eleftherios Venizelos stated in the Greek parliament that "only colossal faults" could separate the region from Greece. Upon Venizelos' resignation in December, however, the succeeding royalist governments were determined to exploit the situation and predetermine the region's future by formally incorporating it into the Greek state. In the first months of 1916, Northern Epirus participated in the Greek elections and elected 16 representatives to the Greek Parliament. In March, the region's union with Greece was officially declared, and the area was divided into the prefectures of Argyrokastro and Korytsa.[43]

Italian–French occupation and Interwar period

The politically unstable situation that followed in Greece during the next months, with the National Schism between royalists and Venizelos’ supporters, divided Greece into two states. This situation, according also to the development of the Balkan Front, led Italian forces in Gjirokastër to enter the area in September 1916, after gaining the approval of the Triple Entente, and to take over most of Northern Epirus. An exception was Korçë which was retaken by French forces from Bulgarian occupation, and turned into the Autonomous Albanian Republic of Korçë under the military protection of the French army. After the war's end in 1918, the tendency to reestablish the autonomy of the region continued.[44]

Under the terms of the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 (the Venizelos-Tittoni agreement), Northern Epirus was to be awarded to Greece, but political developments such as the Greek defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) and strong Italian opposition in favor of Albania caused the area to be finally ceded to Albania in 1921.[4][45]

In February 1922, the Albanian Parliament approved the Declaration of Minority Rights. However, the Declaration, contrary to the Protocol of Corfu, recognized minority rights only in a limited area (parts of Gjirokastër, Sarandë district and 3 villages in Himarë), without implementing any form of local autonomy. All Greek schools in the excluded area were forced to close until 1935, in violation of obligations accepted by the Albanian government at the League of Nations.[46] In 1925, Albania's present borders were set, leading Greece to abandon its claims to Northern Epirus.[47]

The Northern Epirote issue and the autonomy question

From the Albanian perspective, adopted also by Italian and Austrian sources of that time, the Northern Epirote movement was directly supported by the Greek state, with the help of a minority of inhabitants in the region, resulting in chaos and political instability in all of Albania.[48] In Albanian historiography, the Protocol of Corfu is either scarcely mentioned[49] or seen as an attempt to divide the Albanian state and proof of the Great Powers' disregard for Albania's national integrity.[50]

With the ratification of the Protocol of Corfu, the term "Northern Epirus", the state's common name—and consequently that of its citizens, "Northern Epirotes"—acquired official status. However, after the region's cession to Albania, these terms were considered associated with Greek irredentist action and not granted legal status by the Albanian authorities;[51] anyone making use of them was persecuted as an enemy of the state.[52]

The autonomy question remains on the diplomatic agenda in Albanian-Greek relations as part of the Northern Epirote issue.[53] In 1925, Albania's borders were fixed by the Protocol of Florence, and the Kingdom of Greece abandoned all claims to Northern Epirus.[54] In the 1960s, Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev asked his Albanian counterpart about giving autonomy to the Greek minority, with no results.[55][56] In 1991, after the collapse of the communist regime in Albania, the chairman of Greek minority organization Omonoia called for autonomy for Northern Epirus, on the basis that the rights provided for under the Albanian constitution were highly precarious. This proposal was rejected, spurring the minority's radical wing to call for a union with Greece.[57] Two years later, Omonoia's chairman was arrested by the Albanian police after publicly stating that the Greek minority goal was the creation of an autonomous region inside the Albanian borders, based on the provisions of the Protocol of Corfu.[53] In 1997, Albanian analysts stated that the possibility of a Greek minority-inspired breakaway Republic still exists.[58]

See also

References

- ↑ limited use in education, equal in justice and public administration (under the terms of Corfu Protocol).

- ↑ Thomopoulos, Elaine (2012). The History of Greece. ABC-CLIO. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-313-37511-8.

- 1 2 Boeckh 1996: 114

- 1 2 Miller 1966: 543–44

- ↑ Gregory C. Ference, ed. Chronology of 20th Century Eastern European History. 1994.

- ↑ Kondis 1976: p. 93

- ↑ Schurman 1916: "During the first war the Greeks had occupied Epirus or southern Albania as far north as a line drawn from a point a little above Khimara on the coast due east toward Lake Presba, so that the cities of Tepeleni and Koritza were included in the Greek area."

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 51

- ↑ Winnifrith 2002: 130

- 1 2 Miller 1966: 518

- ↑ Nußberger Angelika; Wolfgang Stoppel (2001). "Minderheitenschutz im östlichen Europa (Albanien)" (PDF) (in German). Universität Köln: 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2010-04-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Newman, Bernard (2007). Balkan Background. READ BOOKS. pp. 262–263. ISBN 978-1-4067-5374-5.

- ↑ Winnifrith 2002: 130 "...in Northern Epirus loyalty to an Albania with a variety of Muslim leaders competing in anarchy cannot have been strong".

- ↑ Schurman 1916: 'This new kingdom was called into being by the voice of the European concert at the demand of Austria-Hungary supported by Italy.'

- ↑ Chase 2007: 37–38

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 38

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 32–33 "In view of the opposition of the part of the Dual monarchy...showed his irrecontiliation."

- ↑ Kitromilides 2008: 150–151

- ↑ Greek ministry of Foreign Affairs. Note of the Great Powers to Greece. Archived 2008-12-09 at the Wayback Machine It concerned the decision of the Powers to cede irrevocably to Greece all the Aegean islands already occupied by the latter (with the exception of Imbros, Tenedos and Castellorizo) on the date on which Greek troops would evacuate the parts of Northern Epirus awarded to Albania by the Florence Protocol.

- 1 2 3 Kondis 1976: 124

- ↑ Schurman 1916: "It is little wonder that the Greeks of Epirus feel outraged by the destiny which the European Powers have imposed upon them... Nor is it surprising that since Hellenic armies have evacuated northern Epirus in conformity with the decree of the Great Powers, the inhabitants of the district, all the way from Santi Quaranta to Koritza, are declaring their independence and fighting the Albanians who attempt to bring them under the yoke."

- ↑ The Greek term autonomos can mean either "independent" or "autonomous".

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 42

- ↑ Pyrrhus Ruches. Albanian historical folksongs, 1716–1943: a survey of oral epic poetry from southern Albania, with original texts. Argonaut, 1967 p.106

- ↑ Ruches 1965: 83

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Miller 1966: 519

- ↑ Boeckh 1996: 115

- 1 2 3 Heuberger, Suppan, Vyslonzil 1996: 68–69

- 1 2 3 4 Kondis 1976: 127

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 43

- ↑ Ruches 1965: 84–85

- ↑ Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. p. 380: Ekdotike Athenon. p. 480. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - 1 2 Ruches 1965: 91

- ↑ Miller 1966: 520

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 49

- ↑ Boeckh 1996: 116

- ↑ Ruches 1965: 92–93.

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 50

- ↑ Kondis: 132–133

- ↑ Ruches 1965: 94

- ↑ Leon, George B. (1970). "Greece and the Albanian Question at the Outbreak of the First World War". Institute for Balkan Studies: 61–80 [74].

- ↑ Guy 2007: Greek troops crossed the southern Albanian border at the end of October 1914, officially reoccupying all of southern Albania, exclusive of Vlorë, and establishing a military administration by 27 October 1914, p. 117.

- ↑ Stickney 1924: 57- 63

- ↑ Winnifrith 2002: 132

- ↑ Kitromilides 2008: 162–163

- ↑ Basil Kondis & Eleftheria Manda. The Greek Minority in Albania – A documentary record (1921–1993). Thessaloniki. Institute of Balkan Studies. 1994, p. 20.

- ↑ Brad K. Blitz: War and change in the Balkans: nationalism, conflict and cooperation, Cambridge University Press, 2006. Page 225

- ↑ Ruches 1965: 87

- ↑ Nataša Gregorič Contested Spaces and Negotiated Identities in Dhermi/Drimades of Himare/Himara area, Southern Albania, University of Nova Gorica 2008, p. 144.

- ↑ Miranda Vickers and James Pettifer. Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1997, ISBN 1-85065-290-2, p 2.

- ↑ Russell King; Nicola Mai; Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers, eds. (2005). The New Albanian Migration. Sussex Academic Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-903900-78-9.

- ↑ Two friendly peoples: excerpts from the political diary and other documents on Albanian-Greek relations, 1941–1984. Enver Hoxha, Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin Institute. 1985.

- 1 2 Heuberger, Suppan, Vyslonzil 1996: 73

- ↑ It was not until 1925 that Albania's present borders were fixed through the Florence Protocol, the Kingdom of Greece finally abandoning its claims to northern Epirus. ... in, Brad K. Blitz: War and change in the Balkans: nationalism, conflict and cooperation, Cambridge University Press, 2006. Page 225

- ↑ Miranda Vickers and James Pettifer. Albania: From Anarchy to a Balkan Identity. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1997, ISBN 1-85065-290-2, p. 188-189.

- ↑ Albania and the Sino-Soviet rift William E. Griffith. M. I. T. Press, 1963

- ↑ Working Paper. Albanian Series. Gender Ethnicity and Landed Property in Albania. Sussana Lastaria-Cornhiel, Rachel Wheeler. September 1998. Land Tenure Center. University of Wisconsin, p.38

- ↑ Minorities at Risk Project, Chronology for Greeks in Albania, 2004. Online. UNHCR Refworld accessed 17 March 2009. "Zef Preci, of the Albanian Center for Economic Research says the danger of a Greek minority-inspired breakaway republic is very much alive"

Sources

- Boeckh, Katrin (1996). Von den Balkankriegen zum Ersten Weltkrieg: Kleinstaatenpolitik und ethnische Selbstbestimmung auf dem Balkan (in German). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. p. 418. ISBN 978-3-486-56173-9.

- Chase, George H. (2007) [1943]. Greece of Tomorrow. READ BOOKS. ISBN 978-1-4067-0758-8.

- Glenny, Misha (1999). The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-85338-0.

The Balkans: Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-1999.

- Guy, Nicola (2007). "The Albanian Question in British Policy and the Italian Intervention, August 1914 – April 1915". Diplomacy & Statecraft. Diplomacy & Statecraft, Volume 18, Issue 1. 18: 109–131. doi:10.1080/09592290601163035. S2CID 153894515.

- Kondis, Basil (1976). Greece and Albania, 1908–1914. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9798840949085.

- Kitromilides, Paschalis (2008). Eleftherios Venizelos: The Trials of Statesmanship. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3364-7.

- Miller, William (1966). The Ottoman Empire and Its Successors, 1801–1927. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-1974-3.

- Ruches, Pyrrhus J. (1965). Albania's captives. Chicago: Argonaut.

- Schurman, Jacob Gould (1916). "The Balkan Wars: 1912–1913". Project Gutenberg.

- Stickney, Edith Pierpont (1926). Southern Albania or Northern Epirus in European International Affairs, 1912–1923. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6171-0.

- Valeria Heuberger; Arnold Suppan; Elisabeth Vyslonzil (1996). Brennpunkt Osteuropa: Minderheiten im Kreuzfeuer des Nationalismus (in German). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag. ISBN 978-3-486-56182-1.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). Badlands-borderlands: a history of Northern Epirus/Southern Albania. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-3201-9.

Official documents

- Documents Officiel concernant l'Epire du Nord, 1912–1935. Digital library of the Parliament of Greece. (in French)