%252C_Pompeii%252C_c._79_AD%252C_National_Archaeological_Museum%252C_Naples_-_Spurlock_Museum%252C_UIUC_-_DSC05672_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Roman portraiture was one of the most significant periods in the development of portrait art. The surviving portraits of individuals are almost entirely sculptures, covering a period of almost five centuries. Roman portraiture is characterised by unusual realism and the desire to convey images of nature in the high quality style often seen in ancient Roman art. Some busts even seem to show clinical signs.[1] Several images and statues made in marble and bronze have survived in small numbers. Roman funerary art includes many portraits such as married couple funerary reliefs, which were most often made for wealthy freedmen rather than the patrician elite.

Portrait sculpture from the Republican era tends to be somewhat more modest, realistic, and natural compared to early Imperial works. A typical work might be one like the standing figure "A Roman Patrician with Busts of His Ancestors" (c. 30 B.C.).[2]

By the imperial age, though they were often realistic depictions of human anatomy, portrait sculpture of Roman emperors were often used for propaganda purposes and included ideological messages in the pose, accoutrements, or costume of the figure. Since most emperors from Augustus on were deified, some images are idealized. In the portraiture of Augustus, for example the Blacas Cameo, he is always shown as a man of perhaps about 35, although some images were made when he was in his seventies, The Romans also depicted warriors and heroic adventures, in the spirit of the Greeks who came before them.

Ideology

Religious functions and origins

The origin of the realism of Roman portraits may be, according to some scholars, because they evolved from wax death masks. These death masks were taken from bodies and kept in a home altar. Besides wax, masks were made from bronze, marble and terracotta. The molds for the masks were made directly from the deceased, giving historians an accurate representation of typically Roman features.

Politics

In the days of the Republic, full-size statues of political officials and military commanders were often erected in public places. Such an honor was provided by the decision of the Senate, usually in commemoration of victories, triumphs and political achievements. These portraits were usually accompanied by a dedicatory inscription. If the person commemorated with a portrait was found to have committed a crime, the portrait would be destroyed.

Roman leaders favored the sense of civic duty and military ability over beauty in their portraiture. Veristic portraits, including arguably ugly features, was a way of showing confidence and of placing a value on strength and leadership above superficial beauty. This type of portraiture sought to show what mattered to the Romans; powerful character valued above appearances.

Similarly to Greek rulers, Roman leaders borrowed recognizable features from the appearances of their predecessors. For instance, rulers coming after Alexander the Great copied his distinct hairstyle and intense gaze in their own portraits.[3] This was commonly practiced to suggest their likeness to them in character and their legitimacy to rule; in short, these fictitious additions were meant to persuade their subjects that they would be as great and powerful a leader as the previous ruler had been, even if they did not see eye to eye on all issues.[4]

Choosing to proudly display imperfections in portraiture was an early departure from the idealistic tradition handed down from the Greeks. The apparent indifference toward perfection in physical appearance seems to have led to the eventual abandonment of realism altogether, as we see in the very late Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs.

Social and psychological aspect

Development of the Roman portrait was associated with increased interest in the individual, with the expansion of the social circle portrayed. At the heart of the artistic structure of many Roman portraits is the clear and rigorous transfer of unique features of the model, while still keeping the general style very similar. Unlike the ancient Greek portraits that strived for idealization (the Greeks believed that a good man must be beautiful), Roman portrait sculpture was far more natural and is still considered one of the most realistic samples of the genre in the history of art.

Historical development

Republican period

Portraiture in Republican Rome was a way of establishing societal legitimacy and achieving status through one's family and background. Exploits wrought by one's ancestors earned them and their families public approbation, and more; a pompous state funeral paid for by the state. Wax masks would be cast from the family member while they were still living, which made for hyper-realistic visual representations of the individual literally lifted from their face. These masks would be kept in the houses of male descendants in memory of the ancestors once they had passed. These masks served as a sort of family track record, and could get the descendants positions and perks,[5] similar to a child of two alumni attending their alma mater.

Republican Rome embraced imperfection in portraiture because they sought to embrace the individuality of each portrait sitter.[6]

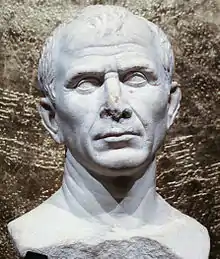

The Capitoline Brutus in the Musei Capitolini, possibly portraying Lucius Junius Brutus, dated late 4th century BC to early 3rd century BC

The Capitoline Brutus in the Musei Capitolini, possibly portraying Lucius Junius Brutus, dated late 4th century BC to early 3rd century BC The Orator, c. 100 BC, an Etrusco-Roman bronze statue depicting Aule Metele (Latin: Aulus Metellus), an Etruscan man wearing a Roman toga while engaged in rhetoric; the statue features an inscription in the Etruscan alphabet

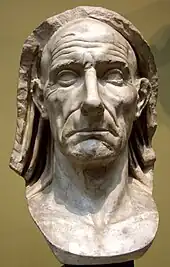

The Orator, c. 100 BC, an Etrusco-Roman bronze statue depicting Aule Metele (Latin: Aulus Metellus), an Etruscan man wearing a Roman toga while engaged in rhetoric; the statue features an inscription in the Etruscan alphabet The Patrician Torlonia bust of Cato the Elder. 1st century BC

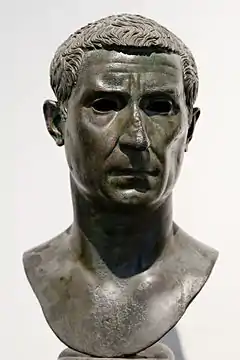

The Patrician Torlonia bust of Cato the Elder. 1st century BC Isis priest (formerly identified as Scipio Africanus), bronze bust, mid 1st century BC

Isis priest (formerly identified as Scipio Africanus), bronze bust, mid 1st century BC

The Grave relief of Publius Aiedius and Aiedia, 30 BC, Pergamon Museum (Berlin)

The Grave relief of Publius Aiedius and Aiedia, 30 BC, Pergamon Museum (Berlin) Roman, Republican or Early Imperial, Relief of a seated poet (Menander) with masks of New Comedy, 1st century BC – early 1st century AD, Princeton University Art Museum

Roman, Republican or Early Imperial, Relief of a seated poet (Menander) with masks of New Comedy, 1st century BC – early 1st century AD, Princeton University Art Museum

Imperial period

Roman portraiture of the Imperial period includes works created throughout the provinces, often combining Greek, Roman, and local traditions, as with the Fayum mummy portraits.

Hellenistic Greek style and leadership expectations carried over into Roman leadership portraiture. One significant example is the Severan Period marble portrait of the emperor Caracalla. Nearly all representations of Caracalla reflect his military prowess through his frighteningly aggressive expression. Caracalla borrowed the precedent Alexander set; the piercing gaze. His arresting confidence exudes from his features to show that he is not a man to be trifled with. The intense sculptural execution of this piece in particular reflects a shift toward more geometric renderings of the human face to better convey messages to the public, often strong implications of power and authority to keep peace in the Roman Empire. Emperors coming after Caracalla saw the respect he commanded of his subordinate governing party as well as the Roman population as a whole. Seeing his success as a ruler, subsequent emperors sought to have portraits similar to Caracalla's to suggest that they were on the same level as him, both in terms of military tenacity and authoritarian control. This facilitated more and more geometric, less idealized figural representations of leaders to constantly emphasize the ruler's strength and image.[4]

This geometric style proved to be useful to the Roman Tetrarchs that divided rule of the empire among themselves after the reign of the emperors. The geometric style of the Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs is not realistic, but the style applied to all four figures sent a message of steadiness and agreements between the four rulers, reassuring Roman citizens while simultaneously sending an unmistakable message of power and authority reminiscent of the previous emperors. Presenting variance in the appearance of the tetrarchs may have contributed to viewers favoring one ruler over the others. Instead, the Tetrarchy chose to show themselves as visually synonymous in this particular piece to show their ontological equality and show the unity and strength of the empire through this representation of all four together.[4] Using near-identical geometric forms to represent their likenesses was the easiest way to show their equality and common will. The abstraction of human form made for a clearer understanding of the expectations Roman Tetrarchs had for their subjects and how Roman citizens expected the Tetrarchs to rule.

L. Calpurnius Piso Pontifex, late 1st century BC–early 1st century AD

L. Calpurnius Piso Pontifex, late 1st century BC–early 1st century AD Portrait of Terentius Neo, a baker and his wife from Pompeii, 20–30 AD

Portrait of Terentius Neo, a baker and his wife from Pompeii, 20–30 AD Young woman with Flavian-era hairstyle, 80s–90s AD

Young woman with Flavian-era hairstyle, 80s–90s AD

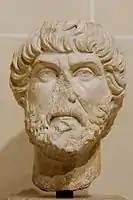

Antinous, ca. 130 AD

Antinous, ca. 130 AD_01.jpg.webp) Vibia Sabina, ca. 130 AD

Vibia Sabina, ca. 130 AD.jpg.webp)

Mummy portrait from Roman Egypt, 2nd–3rd century AD

Mummy portrait from Roman Egypt, 2nd–3rd century AD.jpg.webp) Bust of Augustus, a fine example of Roman portraiture

Bust of Augustus, a fine example of Roman portraiture Ancient bust of Roman emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161–169 AD), a natural blond who would sprinkle gold dust in his hair to make it even blonder,[7] Bardo National Museum, Tunis

Ancient bust of Roman emperor Lucius Verus (r. 161–169 AD), a natural blond who would sprinkle gold dust in his hair to make it even blonder,[7] Bardo National Museum, Tunis Remnants of a Roman bust of a youth with a blond beard, perhaps depicting Roman emperor Commodus (r. 177–192 AD), National Archaeological Museum, Athens

Remnants of a Roman bust of a youth with a blond beard, perhaps depicting Roman emperor Commodus (r. 177–192 AD), National Archaeological Museum, Athens Portrait of the emperor Gordianus I (238) on a bronze sestertius

Portrait of the emperor Gordianus I (238) on a bronze sestertius_und_ihre_Kinder.jpg.webp)

Portrait of Constantius Chlorus (r. 293–306 AD)

Portrait of Constantius Chlorus (r. 293–306 AD) Colossus of Constantine, 312–315 AD

Colossus of Constantine, 312–315 AD Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs, Venice

Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs, Venice Bust depicting an idealized portrait of Menander of Ephesus, 4th century AD, Ephesus Archaeological Museum

Bust depicting an idealized portrait of Menander of Ephesus, 4th century AD, Ephesus Archaeological Museum Marble bust of an orator or philosopher, 5th century AD, Louvre

Marble bust of an orator or philosopher, 5th century AD, Louvre

See also

References

- ↑ Engmann B: Neurologic diseases in ancient Roman sculpture busts. Neurol Clin Pract December 2013 vol.3 no.6:539-541. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e3182a78f02

- ↑ Janson, p. 197

- ↑ Stewart, Andrew F. “The Alexander Mosaic: A Reading.” Faces of Power: Alexander's Image and Hellenistic Politics, University of California Press, 1993, pp. 140–141.

- 1 2 3 Trentinella, Rosemarie (October 2003). "Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ↑ Pollini, John. "Ritualizing Death". From Republic to Empire Rhetoric, Religion, and Power in the Visual Culture of Ancient Rome. pp. 13, 19.

- ↑ Kleiner, Diana E. E. (1992). Roman sculpture. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0-300-04631-6. OCLC 25050500.

- ↑ Michael Grant (1994). The Antonines: The Roman Empire in Transition. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10754-7, pp 27-28.

- ↑ Daniel Thomas Howells (2015). "A Catalogue of the Late Antique Gold Glass in the British Museum (PDF)." London: the British Museum (Arts and Humanities Research Council). Accessed 2 October 2016, p. 7.

- ↑ Jás Elsner (2007). "The Changing Nature of Roman Art and the Art Historical Problem of Style," in Eva R. Hoffman (ed), Late Antique and Medieval Art of the Medieval World, 11-18. Oxford, Malden & Carlton: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-2071-5, p. 17, Figure 1.3 on p. 18.

Bibliography

- (in Italian) Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli, Il problema del ritratto, in L'arte classica, Editori Riuniti, Rome 1984.

- (in Italian) Ranuccio Bianchi Bandinelli e Mario Torelli, L'arte dell'antichità classica, Etruria-Roma, Utet, Turin 1976.

- (in Italian) Pierluigi De Vecchi & Elda Cerchiari, I tempi dell'arte, volume 1, Bompiani, Milan 1999

- http://www.getty.edu/publications/virtuallibrary/0866590048.html?imprint=jpgt&pg=6&res=20