| Santa Teresa Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Late Oligocene (Deseadan) ~ | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Underlies | alluvium |

| Overlies | San Juan de Río Seco Formation |

| Thickness | Type section: 118 m (387 ft) Maximum: 150 m (490 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Claystone |

| Other | Siltstone, calcareous sandstone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 4°50′55″N 74°37′14″W / 4.84861°N 74.62056°W |

| Country | |

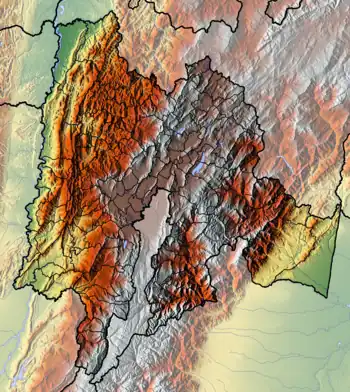

| Extent | Western Eastern Ranges, Andes Southern Middle Magdalena Valley |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Vereda Santa Teresa |

| Named by | De Porta |

| Location | San Juan de Rioseco |

| Year defined | 1966 |

| Coordinates | 4°50′55″N 74°37′14″W / 4.84861°N 74.62056°W |

| Region | Cundinamarca |

| Country | |

| Thickness at type section | 118 m (387 ft) |

Paleogeography of Northern South America 35 Ma, by Ron Blakey | |

The Santa Teresa Formation (Spanish: Formación Santa Teresa, Tist, Pgst) is a geological formation of the western Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes, west of the Bituima Fault, and the southern Middle Magdalena Valley. The formation spreads across the western part of Cundinamarca and the northern portion of Tolima. The formation consists of grey claystones intercalated by orange quartz siltstones and sandstones of small to conglomeratic grain size. The thickness at its type section has been measured to be 118 metres (387 ft) and a maximum thickness of 150 metres (490 ft) suggested.

In the formation, dated on the basis of its fossil content to the Late Oligocene, many leaf imprints and mollusks were found, suggesting a lacustrine to deltaic depositional environment with periodical marine incursions.

Etymology

The formation was defined by De Porta in 1966 and named after the vereda Santa Teresa, San Juan de Rioseco.[1]

Description

The Santa Teresa Formation is the youngest unit outcropping in the Jerusalén-Guaduas synclinal, western Eastern Ranges, covering the San Juan de Río Seco Formation. The formation was formerly called La Cira Formation. In the Balú quebrada, the formation shows a thickness of 118 metres (387 ft), while the maximum thickness could reach 150 metres (490 ft).[1]

The lower boundary of the formation is marked by the first occurrence of grey claystones, covering the light brown claystones of the San Juan de Río Seco Formation. The formation comprises grey claystones intercalated by orange quartz siltstones and sandstones of small to conglomeratic grain size. The roundness of the sandstone grains has been characterized as angular to subangular by Lamus Ochoa et al. in 2013.[2] The claystones occur in thick layers with wavy lamination.[1]

In these thick packages of claystones, the formation has provided fossil leaves in various forms and sizes, and to a lesser extent the remains of mollusks; gastropods and bivalves. The basal contacts of these beds are straight to transitional and most of the time are coarsening upward towards quartz arenites where the gastropods dominate. These facies sequences have a thickness of about 2 metres (6.6 ft). Locally, bioturbation, siderite nodules and coal beds occur in the formation. The sandstones occur in very thin to very thick beds, characterized by plain parallel lamination, in lenses and very locally in flasers. The cement of the arenites is calcareous.[1] The grain composition of the lithic fraction comprises zircon,[3] epidote, zoisite, clinozoisite and pyroxenes, which at the top of the formation amounts to 86 percent.[4]

Stratigraphy and depositional environment

The Santa Teresa Formation conformably overlies the San Juan de Río Seco Formation and is covered by subrecent alluvium.[1] The formation is part of the sequence after the Eocene unconformity.[5]

The age has been inferred to be Late Oligocene. The depositional environment has been interpreted as lacustrine with marine influence in the form of channels. The abundance of brackish and fresh water gastropods suggests these environmental conditions prevailed in the Oligocene of central Colombia.[1]

In the type section at the Balú quebrada, facies traits that confirm this interpretation can be observed. The lacustrine areas were probably shallow water environments with reducing conditions and a continuous supply of siliciclastics by small deltas. The many leaf imprints and coal layers support the presence of a lush vegetation at the time of deposition.[1] The abundance of lithic clasts near the top of the formation supports a renewed provenance area to the east; the uplift of the Eastern Ranges of the Colombian Andes,[6] due to activity of the La Salina Fault.[7]

Paleontology

The Santa Teresa Formation has provided fossil mollusks, described by De Porta and Solé De Porta in 1962 and De Porta Anodontites laciranus, Diplodon oponcintonis, Diplodon waringi,[8] and Corbula sp., among other mollusks described by De Porta in 1966.[1]

Regional correlations

| Ma | Age | Paleomap | Regional events | Catatumbo | Cordillera | proximal Llanos | distal Llanos | Putumayo | VSM | Environments | Maximum thickness | Petroleum geology | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | Holocene |  | Holocene volcanism Seismic activity | alluvium | Overburden | ||||||||

| 1 | Pleistocene |  | Pleistocene volcanism Andean orogeny 3 Glaciations | Guayabo | Soatá Sabana | Necesidad | Guayabo | Gigante Neiva | Alluvial to fluvial (Guayabo) | 550 m (1,800 ft) (Guayabo) | [9][10][11][12] | ||

| 2.6 | Pliocene |  | Pliocene volcanism Andean orogeny 3 GABI | Subachoque | |||||||||

| 5.3 | Messinian | Andean orogeny 3 Foreland | Marichuela | Caimán | Honda | [11][13] | |||||||

| 13.5 | Langhian | Regional flooding | León | hiatus | Caja | León | Lacustrine (León) | 400 m (1,300 ft) (León) | Seal | [12][14] | |||

| 16.2 | Burdigalian | Miocene inundations Andean orogeny 2 | C1 | Carbonera C1 | Ospina | Proximal fluvio-deltaic (C1) | 850 m (2,790 ft) (Carbonera) | Reservoir | [13][12] | ||||

| 17.3 | C2 | Carbonera C2 | Distal lacustrine-deltaic (C2) | Seal | |||||||||

| 19 | C3 | Carbonera C3 | Proximal fluvio-deltaic (C3) | Reservoir | |||||||||

| 21 | Early Miocene | Pebas wetlands | C4 | Carbonera C4 | Barzalosa | Distal fluvio-deltaic (C4) | Seal | ||||||

| 23 | Late Oligocene |  | Andean orogeny 1 Foredeep | C5 | Carbonera C5 | Orito | Proximal fluvio-deltaic (C5) | Reservoir | [10][13] | ||||

| 25 | C6 | Carbonera C6 | Distal fluvio-lacustrine (C6) | Seal | |||||||||

| 28 | Early Oligocene | C7 | C7 | Pepino | Gualanday | Proximal deltaic-marine (C7) | Reservoir | [10][13][15] | |||||

| 32 | Oligo-Eocene | C8 | Usme | C8 | onlap | Marine-deltaic (C8) | Seal Source | [15] | |||||

| 35 | Late Eocene |  | Mirador | Mirador | Coastal (Mirador) | 240 m (790 ft) (Mirador) | Reservoir | [12][16] | |||||

| 40 | Middle Eocene | Regadera | hiatus | ||||||||||

| 45 | |||||||||||||

| 50 | Early Eocene |  | Socha | Los Cuervos | Deltaic (Los Cuervos) | 260 m (850 ft) (Los Cuervos) | Seal Source | [12][16] | |||||

| 55 | Late Paleocene | PETM 2000 ppm CO2 | Los Cuervos | Bogotá | Gualanday | ||||||||

| 60 | Early Paleocene | SALMA | Barco | Guaduas | Barco | Rumiyaco | Fluvial (Barco) | 225 m (738 ft) (Barco) | Reservoir | [9][10][13][12][17] | |||

| 65 | Maastrichtian |  | KT extinction | Catatumbo | Guadalupe | Monserrate | Deltaic-fluvial (Guadalupe) | 750 m (2,460 ft) (Guadalupe) | Reservoir | [9][12] | |||

| 72 | Campanian | End of rifting | Colón-Mito Juan | [12][18] | |||||||||

| 83 | Santonian | Villeta/Güagüaquí | |||||||||||

| 86 | Coniacian | ||||||||||||

| 89 | Turonian | Cenomanian-Turonian anoxic event | La Luna | Chipaque | Gachetá | hiatus | Restricted marine (all) | 500 m (1,600 ft) (Gachetá) | Source | [9][12][19] | |||

| 93 | Cenomanian |  | Rift 2 | ||||||||||

| 100 | Albian | Une | Une | Caballos | Deltaic (Une) | 500 m (1,600 ft) (Une) | Reservoir | [13][19] | |||||

| 113 | Aptian |  | Capacho | Fómeque | Motema | Yaví | Open marine (Fómeque) | 800 m (2,600 ft) (Fómeque) | Source (Fóm) | [10][12][20] | |||

| 125 | Barremian | High biodiversity | Aguardiente | Paja | Shallow to open marine (Paja) | 940 m (3,080 ft) (Paja) | Reservoir | [9] | |||||

| 129 | Hauterivian |  | Rift 1 | Tibú- Mercedes | Las Juntas | hiatus | Deltaic (Las Juntas) | 910 m (2,990 ft) (Las Juntas) | Reservoir (LJun) | [9] | |||

| 133 | Valanginian | Río Negro | Cáqueza Macanal Rosablanca | Restricted marine (Macanal) | 2,935 m (9,629 ft) (Macanal) | Source (Mac) | [10][21] | ||||||

| 140 | Berriasian | Girón | |||||||||||

| 145 | Tithonian | Break-up of Pangea | Jordán | Arcabuco | Buenavista Batá | Saldaña | Alluvial, fluvial (Buenavista) | 110 m (360 ft) (Buenavista) | "Jurassic" | [13][22] | |||

| 150 | Early-Mid Jurassic |  | Passive margin 2 | La Quinta | Montebel Noreán | hiatus | Coastal tuff (La Quinta) | 100 m (330 ft) (La Quinta) | [23] | ||||

| 201 | Late Triassic |  | Mucuchachi | Payandé | [13] | ||||||||

| 235 | Early Triassic |  | Pangea | hiatus | "Paleozoic" | ||||||||

| 250 | Permian |  | |||||||||||

| 300 | Late Carboniferous |  | Famatinian orogeny | Cerro Neiva () | [24] | ||||||||

| 340 | Early Carboniferous | Fossil fish Romer's gap | Cuche (355-385) | Farallones () | Deltaic, estuarine (Cuche) | 900 m (3,000 ft) (Cuche) | |||||||

| 360 | Late Devonian |  | Passive margin 1 | Río Cachirí (360-419) | Ambicá () | Alluvial-fluvial-reef (Farallones) | 2,400 m (7,900 ft) (Farallones) | [21][25][26][27][28] | |||||

| 390 | Early Devonian |  | High biodiversity | Floresta (387-400) El Tíbet | Shallow marine (Floresta) | 600 m (2,000 ft) (Floresta) | |||||||

| 410 | Late Silurian | Silurian mystery | |||||||||||

| 425 | Early Silurian | hiatus | |||||||||||

| 440 | Late Ordovician |  | Rich fauna in Bolivia | San Pedro (450-490) | Duda () | ||||||||

| 470 | Early Ordovician | First fossils | Busbanzá (>470±22) Chuscales Otengá | Guape () | Río Nevado () | Hígado () | [29][30][31] | ||||||

| 488 | Late Cambrian |  | Regional intrusions | Chicamocha (490-515) | Quetame () | Ariarí () | SJ del Guaviare (490-590) | San Isidro () | [32][33] | ||||

| 515 | Early Cambrian | Cambrian explosion | [31][34] | ||||||||||

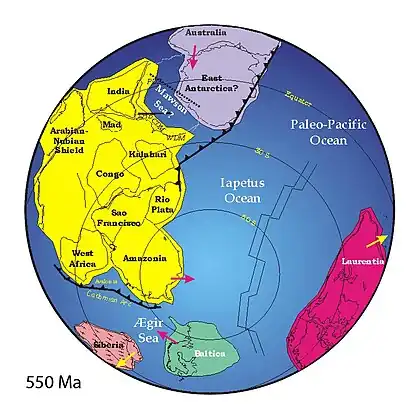

| 542 | Ediacaran |  | Break-up of Rodinia | pre-Quetame | post-Parguaza | El Barro () | Yellow: allochthonous basement (Chibcha Terrane) Green: autochthonous basement (Río Negro-Juruena Province) | Basement | [35][36] | ||||

| 600 | Neoproterozoic | Cariri Velhos orogeny | Bucaramanga (600-1400) | pre-Guaviare | [32] | ||||||||

| 800 |  | Snowball Earth | [37] | ||||||||||

| 1000 | Mesoproterozoic |  | Sunsás orogeny | Ariarí (1000) | La Urraca (1030-1100) | [38][39][40][41] | |||||||

| 1300 | Rondônia-Juruá orogeny | pre-Ariarí | Parguaza (1300-1400) | Garzón (1180-1550) | [42] | ||||||||

| 1400 |  | pre-Bucaramanga | [43] | ||||||||||

| 1600 | Paleoproterozoic | Maimachi (1500-1700) | pre-Garzón | [44] | |||||||||

| 1800 | Tapajós orogeny | Mitú (1800) | [42][44] | ||||||||||

| 1950 | Transamazonic orogeny | pre-Mitú | [42] | ||||||||||

| 2200 | Columbia | ||||||||||||

| 2530 | Archean |  | Carajas-Imataca orogeny | [42] | |||||||||

| 3100 | Kenorland | ||||||||||||

| Sources | |||||||||||||

- Legend

- group

- important formation

- fossiliferous formation

- minor formation

- (age in Ma)

- proximal Llanos (Medina)[note 1]

- distal Llanos (Saltarin 1A well)[note 2]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Acosta & Ulloa, 2001, p.64

- ↑ Lamus Ochoa et al., 2013, p.29

- ↑ Lamus Ochoa et al., 2013, p.34

- ↑ Lamus Ochoa et al., 2013, p.32

- ↑ Lamus Ochoa et al., 2013, p.22

- ↑ Lamus Ochoa et al., 2013, p.35

- ↑ Caballero et al., 2010, p.74

- ↑ Acosta Garay et al., 2002, p.49

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 García González et al., 2009, p.27

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 García González et al., 2009, p.50

- 1 2 García González et al., 2009, p.85

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Barrero et al., 2007, p.60

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Barrero et al., 2007, p.58

- ↑ Plancha 111, 2001, p.29

- 1 2 Plancha 177, 2015, p.39

- 1 2 Plancha 111, 2001, p.26

- ↑ Plancha 111, 2001, p.24

- ↑ Plancha 111, 2001, p.23

- 1 2 Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.32

- ↑ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.30

- 1 2 Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.21-26

- ↑ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, p.28

- ↑ Correa Martínez et al., 2019, p.49

- ↑ Plancha 303, 2002, p.27

- ↑ Terraza et al., 2008, p.22

- ↑ Plancha 229, 2015, pp.46-55

- ↑ Plancha 303, 2002, p.26

- ↑ Moreno Sánchez et al., 2009, p.53

- ↑ Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.43

- ↑ Manosalva Sánchez et al., 2017, p.84

- 1 2 Plancha 303, 2002, p.24

- 1 2 Mantilla Figueroa et al., 2015, p.42

- ↑ Arango Mejía et al., 2012, p.25

- ↑ Plancha 350, 2011, p.49

- ↑ Pulido & Gómez, 2001, pp.17-21

- ↑ Plancha 111, 2001, p.13

- ↑ Plancha 303, 2002, p.23

- ↑ Plancha 348, 2015, p.38

- ↑ Planchas 367-414, 2003, p.35

- ↑ Toro Toro et al., 2014, p.22

- ↑ Plancha 303, 2002, p.21

- 1 2 3 4 Bonilla et al., 2016, p.19

- ↑ Gómez Tapias et al., 2015, p.209

- 1 2 Bonilla et al., 2016, p.22

- 1 2 Duarte et al., 2019

- ↑ García González et al., 2009

- ↑ Pulido & Gómez, 2001

- ↑ García González et al., 2009, p.60

Bibliography

See also sources for the correlation table

- Acosta Garay, Jorge, and Carlos E. Ulloa Melo. 2001. Geología de la Plancha 227 La Mesa - 1:100,000, 1–80. INGEOMINAS.

- Acosta Garay, Jorge Enrique; Rafael Guatame; Juan Carlos Caicedo A., and Jorge Ignacio Cárdenas. 2002. Geología de la Plancha 245 Girardot - 1:100,000, 1–101. INGEOMINAS.

- Caballero, Víctor; Mauricio Parra, and Andrés Roberto Mora Bohórquez. 2010. Levantamiento de la Cordillera Oriental de Colombia durante el Eoceno tardío – Oligoceno temprano: Proveniencia sedimentaria en el Sinclinal de Nuevo Mundo, Cuenca Valle Medio del Magdalena, 45–77. 32; Boletín de Geología.

- Lamus Ochoa, Felipe; Germán Bayona; Agustín Cardona, and Andrés Mora. 2013. Procedencia de las unidades cenozoicas del Sinclinal de Guaduas: implicación en la evolución tectónica del sur del Valle Medio del Magdalena y orógenos adyacentes, 1–42. 35; Boletín de Geología.

Maps

- Barrero, Darío, and Carlos J. Vesga. 2010. Plancha 207 - Honda - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-06.

- Barrero, Darío, and Carlos J. Vesga. 2010. Plancha 226 - Líbano - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-06.

- Ulloa, Carlos E.; Erasmo Rodríguez, and Jorge E. Acosta. 1998. Plancha 227 - La Mesa - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-06.

- Acosta, Jorge E.; Rafael Guatame; Oscar Torres, and Frank Solano. 1999. Plancha 245 - Girardot - 1:100,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-06-06.