The Spanish Empire,[lower-alpha 2] sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy[lower-alpha 3] or the Catholic Monarchy,[lower-alpha 4][5][6][7] was a colonial empire governed by Spain between 1492 and 1976.[8][9] In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it was the first empire to usher the European Age of Discovery and achieve a global scale,[10] controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa, various islands in Asia and Oceania, as well as territory in other parts of Europe.[11] It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, becoming known as "the empire on which the sun never sets".[12] At its greatest extent in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Empire covered over 13 million square kilometres (5 million square miles), making it one of the largest empires in history.[4]

An important element in the formation of Spain's empire was the dynastic union between Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon in 1469, known as the Catholic Monarchs, which initiated political, religious and social cohesion but not political unification.[13] Castile (formed in 1230 from the Kingdoms of Leon and Asturias) became the dominant kingdom in Iberia because of its jurisdiction over the overseas empire in the Americas.[14] The structure of the empire was further defined under the Spanish Habsburgs (1516–1700), and under the Spanish Bourbon monarchs, the empire was brought under greater crown control and increased its revenues from the Indies.[15][16] The crown's authority in the Indies was enlarged by the papal grant of powers of patronage, giving it power in the religious sphere.[17][18]

In the beginning, Portugal was the only serious threat to Spanish hegemony in the New World. To end the threat of Portuguese expansion, Spain invaded its Iberian neighbour in 1580, defeating Portuguese, French, and English forces. After the Spanish victory in the War of the Portuguese Succession, Philip II of Spain obtained the Portuguese crown in 1581, and Portugal and its overseas territories came under his rule with the so-called Iberian Union, considered by some historians as a Spanish conquest.[19][20][21][22] Philip respected a certain degree of autonomy in its Iberian territories and, together with the other peninsular councils, established the Council of Portugal, which oversaw Portugal and its empire and "preserv[ed] its own laws, institutions, and monetary system, and united only in sharing a common sovereign."[23] In 1640, while Spain was fighting in Catalonia, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands, Portugal revolted and re-established its independence under the House of Braganza.[24] Iberian kingdoms retained their political identities, with particular administration and juridical configurations. Although the power of the Spanish sovereign as monarch varied from one territory to another, the monarch acted as such in a unitary manner[25] over all the ruler's territories through a system of councils: the unity did not mean uniformity.[26]

Following the Italian Wars against France, which concluded in 1559, Spain emerged with control over half of Italy (Kingdom of Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, and the Duchy of Milan) with the Treaty of Cateau-Cambrésis. The Habsburg Netherlands came under Spanish rule following the abdication of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, in 1555. A war against Spanish rule erupted in the Netherlands, with the Spanish unable to pacify the northern provinces. However, under the leadership of Alessandro Farnese, the Spanish managed to subdue the southern provinces, which became the Spanish Netherlands (present-day Belgium and Luxembourg). These territories remained under Spanish rule until the War of the Spanish Succession.

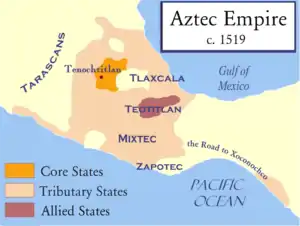

Beginning with the 1492 arrival of Christopher Columbus and continuing for over three centuries, the Spanish Empire would expand across the Caribbean Islands, half of South America, most of Central America and much of North America. In the 16th century, the Spanish Empire conquered and incorporated the Aztec and Inca empires, retaining indigenous elites loyal to the Spanish crown and converts to Christianity as intermediaries between their communities and royal government.[27][28] After a short period of delegation of authority by the crown in the Americas, the crown asserted control over those territories and established the Council of the Indies to oversee rule there.[29] The crown then established viceroyalties in the two main areas of settlement, New Spain and Peru, both regions of dense indigenous populations and mineral wealth. The Maya were finally conquered in 1697. The Magellan-Elcano circumnavigation—the first circumnavigation of the Earth—laid the foundation for Spain's Pacific empire and for Spanish control over the East Indies. In the early 1500s, Spanish forces captured several Muslim cities in North Africa, forcing them to pay tribute to Spain.[30]

The structure of governance of its overseas empire was significantly reformed in the late 18th century by the Bourbon monarchs. Although the Crown of Castile attempted to keep its empire a closed economic system under Habsburg rule, Castile was unable to supply the Indies with sufficient consumer goods to meet demand. This allowed foreign merchants from Genoa, France, England, Germany, and the Netherlands to take advantage of the trade, with silver from the mines of Peru and New Spain flowing to other parts of Europe. The merchant guild of Seville (later Cádiz) served as middlemen in the trade. The crown's trade monopoly was broken early in the 17th century, with the crown colluding with the merchant guild for fiscal reasons in circumventing the supposedly closed system.[31] Spain was largely able to defend its territories in the Americas, with the Dutch, English, and French taking only small Caribbean islands and outposts, using them to engage in contraband trade with the Spanish populace in the Indies.

Spain experienced its greatest territorial losses during the early 19th century, when its colonies in the Americas began fighting their wars of independence.[32] By 1900, Spain had also lost its colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific, and it was left with only its African possessions. In Latin America, among the legacies of its relationship with Iberia, Spanish is the dominant language, Catholicism the main religion, and political traditions of representative government can be traced to the Spanish Constitution of 1812.

Catholic Monarchs and origins of the empire

With the marriage of the heirs apparent to their respective thrones Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile created a personal union that most scholars view as the foundation of the Spanish monarchy. The union of the Crowns of Castile and Aragon joined the economic and military power of Iberia under one dynasty, the House of Trastámara. Their dynastic alliance was important for a number of reasons, ruling jointly over a number of kingdoms and other territories, mostly in the western Mediterranean region, under their respective legal and administrative status. They successfully pursued expansion in Iberia in the Christian conquest of the Muslim Emirate of Granada, completed in 1492, for which Valencia-born Pope Alexander VI gave them the title of the Catholic Monarchs. Ferdinand of Aragon was particularly concerned with expansion in France and Italy, as well as conquests in North Africa.[33]

The concept of 'Early Modern Spain' as a subject of study is muddled.[34] The composite monarchy of the Habsburgs had no official name.[35] In the Early Modern period, as a geographical (non-political) concept and following the medieval tradition, the term 'Spain' could refer to the entire Iberian Peninsula.[36] The term 'Catholic Monarchy' (Spanish: Monarquía Católica, already mentioned in a 1494 papal bull) was common during the reign of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, insofar as the regime strived towards the realization of the idea of universal (that is, Catholic) monarchy.[35] Later in time, other denominations such as 'Spanish Monarchy' (Spanish: Monarquía Española) or 'Monarchy of Spain' (Spanish: Monarquía de España, already mentioned in 1597) would also become common to refer to the composite monarchy.[37] The official titles of the monarchs made no mention to monarchies nor crowns, but focused on the inherited kingdoms and other possessions.[38]

With the Ottoman Turks controlling the choke points of the overland trade from Asia and the Middle East, both Spain and Portugal sought alternative routes. The Kingdom of Portugal had an advantage over the Crown of Castile, having earlier retaken territory from the Muslims. Following Portugal's earlier completion of the reconquest and its establishment of settled boundaries, it began to seek overseas expansion, first to the port of Ceuta (1415) and then by colonizing the Atlantic islands of Madeira (1418) and the Azores (1427–1452); it also began voyages down the west coast of Africa in the fifteenth century.[39] Its rival Castile laid claim to the Canary Islands (1402) and retook territory from the Moors in 1462. The Christian rivals Castile and Portugal came to formal agreements over the division of new territories in the Treaty of Alcaçovas (1479), as well as securing the crown of Castile for Isabella whose accession was challenged militarily by Portugal.

Following the voyage of Christopher Columbus in 1492 and first major settlement in the New World in 1493, Portugal and Castile divided the world by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which gave Portugal Africa and Asia, and the Western Hemisphere to Spain.[40] The voyage of Columbus, a Genoese mariner, obtained the support of Isabella of Castile, sailing west in 1492, seeking a route to the Indies. Columbus unexpectedly encountered the New World, populated by peoples he named "Indians". Subsequent voyages and full-scale settlements of Spaniards followed, with gold beginning to flow into Castile's coffers. Managing the expanding empire became an administrative issue. The reign of Ferdinand and Isabella began the professionalization of the apparatus of government in Spain, which led to a demand for men of letters (letrados) who were university graduates (licenciados), of Salamanca, Valladolid, Complutense and Alcalá. These lawyer-bureaucrats staffed the various councils of state, eventually including the Council of the Indies and Casa de Contratación, the two highest bodies in metropolitan Spain for the government of the empire in the New World, as well as royal government in the Indies.

Early expansion

Fall of Granada

During the last 250 years of the Reconquista era, the Castilian monarchy tolerated the small Moorish taifa client-kingdom of Granada in the south-east by exacting tributes of gold—the parias. In so doing, they ensured that gold from the Niger region of Africa entered Europe.[41]

When King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella I captured Granada in 1492, they implemented policies to maintain control of the territory.[42] To do so, the monarchy implemented a system of encomienda.[43] Encomienda was a method of land control and distribution based upon vassalic ties. Land would be granted to a noble family, who were then responsible for farming and defending it. This eventually led to a large land based aristocracy, a separate ruling class that the crown later tried to eliminate in its overseas colonies. By implementing this method of political organization, the crown was able to implement new forms of private property without completely replacing already existing systems, such as the communal use of resources. After the military and political conquest, there was an emphasis on religious conquest as well, leading to the creation of the Spanish Inquisition.[44] Although the Inquisition was technically a part of the Catholic church, Ferdinand and Isabella formed a separate Spanish Inquisition, which led to mass expulsion of Muslims and Jews from the peninsula. This religious court system was later adopted and transported to the Americas, though they took a less effective role there due to limited jurisdiction and large territories.

Campaigns in North Africa

With the Christian reconquest completed in the Iberian peninsula, Spain began trying to take territory in Muslim North Africa. It had conquered Melilla in 1497, and further expansionism policy in North Africa was developed during the regency of Ferdinand the Catholic in Castile, stimulated by Cardinal Cisneros. Several towns and outposts in the North African coast were conquered and occupied by Castile: Mazalquivir (1505), Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera (1508), Oran (1509), Tunis, Bougie and Tripoli (1510). Algiers was forced to pay tribute to Castile until Ottoman intervention. On the Atlantic coast, Spain took possession of the outpost of Santa Cruz de la Mar Pequeña (1476) with support from the Canary Islands, and it was retained until 1525 with the consent of the Treaty of Cintra (1509). The Ottoman Turks expelled the Spaniards from their coastal possessions, including Algiers in 1529, replacing them with Janissary garrisons to extend their rule into the central Maghrib.[45] However, Oran remained under Spanish control while Tlemcen became tributary to the city.[lower-alpha 5]

Navarre and struggles for Italy

The Catholic Monarchs had developed a strategy of marriages for their children to isolate their long-time enemy: France. The Spanish princesses married the heirs of Portugal, England and the House of Habsburg. Following the same strategy, the Catholic Monarchs decided to support the Aragonese house of the Kingdom of Naples against Charles VIII of France in the Italian Wars beginning in 1494. Ferdinand's general Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba took over Naples after defeating the French at the Battle of Cerignola and the Battle of Garigliano in 1503. In these battles, which established the supremacy of the Spanish Tercios in European battlefields, the forces of the kings of Spain acquired a reputation for invincibility that would last until the 1643 Battle of Rocroi.

After the death of Queen Isabella in 1504, and her exclusion of Ferdinand from a further role in Castile, Ferdinand married Germaine de Foix in 1505, cementing an alliance with France. Had that couple had a surviving heir, probably the Crown of Aragon would have been split from Castile, which was inherited by Charles, Ferdinand and Isabella's grandson.[49] Ferdinand joined the League of Cambrai against Venice in 1508. In 1511, he became part of the Holy League against France, seeing a chance at taking both Milan—to which he held a dynastic claim—and Navarre. In 1516, France agreed to a truce that left Milan in its control and recognized Spanish control of Upper Navarre, which had effectively been a Spanish protectorate following a series of treaties in 1488, 1491, 1493, and 1495.[50]

Canary Islands

Portugal obtained several papal bulls that acknowledged Portuguese control over the discovered territories, but Castile also obtained from the Pope the safeguard of its rights to the Canary Islands with the bulls Romani Pontifex dated 6 November 1436 and Dominatur Dominus dated 30 April 1437.[51] The conquest of the Canary Islands, inhabited by Guanche people, began in 1402 during the reign of Henry III of Castile, by Norman nobleman Jean de Béthencourt under a feudal agreement with the crown. The conquest was completed with the campaigns of the armies of the Crown of Castile between 1478 and 1496, when the islands of Gran Canaria (1478–1483), La Palma (1492–1493), and Tenerife (1494–1496) were subjugated.[40] By 1504, more than 90 percent of the indigenous Canarians had been killed or enslaved.

Rivalry with Portugal

The Portuguese tried in vain to keep secret their discovery of the Gold Coast (1471) in the Gulf of Guinea, but the news quickly caused a huge gold rush. Chronicler Pulgar wrote that the fame of the treasures of Guinea "spread around the ports of Andalusia in such way that everybody tried to go there".[52] Worthless trinkets, Moorish textiles, and above all, shells from the Canary and Cape Verde islands were exchanged for gold, slaves, ivory and Guinea pepper.

The War of the Castilian Succession (1475–79) provided the Catholic Monarchs with the opportunity not only to attack the main source of the Portuguese power, but also to take possession of this lucrative commerce. The Crown officially organized this trade with Guinea: every caravel had to secure a government license and to pay a tax on one-fifth of their profits (a receiver of the customs of Guinea was established in Seville in 1475—the ancestor of the future and famous Casa de Contratación).[53]

Castilian fleets fought in the Atlantic Ocean, temporarily occupying the Cape Verde islands (1476), conquering the city of Ceuta in the Tingitan Peninsula in 1476 (but retaken by the Portuguese),[lower-alpha 6][lower-alpha 7] and even attacked the Azores islands, being defeated at Praia.[lower-alpha 8][lower-alpha 9] The turning point of the war came in 1478, however, when a Castilian fleet sent by King Ferdinand to conquer Gran Canaria lost men and ships to the Portuguese who expelled the attack,[54] and a large Castilian armada—full of gold—was entirely captured in the decisive Battle of Guinea.[55][lower-alpha 10]

The Treaty of Alcáçovas (4 September 1479), while assuring the Castilian throne to the Catholic Monarchs, reflected the Castilian naval and colonial defeat:[56] "War with Castile broke out waged savagely in the Gulf [of Guinea] until the Castilian fleet of thirty-five sail was defeated there in 1478. As a result of this naval victory, at the Treaty of Alcáçovas in 1479 Castile, while retaining her rights in the Canaries, recognized the Portuguese monopoly of fishing and navigation along the whole west African coast and Portugal's rights over the Madeira, Azores and Cape Verde islands [plus the right to conquer the Kingdom of Fez ]."[57] The treaty delimited the spheres of influence of the two countries,[58] establishing the principle of the Mare clausum.[59] It was confirmed in 1481 by the Pope Sixtus IV, in the papal bull Æterni regis (dated on 21 June 1481).[60]

However, this experience would prove to be profitable for future Spanish overseas expansion, because as the Spaniards were excluded from the lands discovered or to be discovered from the Canaries southward[61]—and consequently from the road to India around Africa[62]—they sponsored the voyage of Columbus towards the west (1492) in search of Asia to trade in its spices, encountering the Americas instead.[63] Thus, the limitations imposed by the Alcáçovas treaty were overcome and a new and more balanced division of the world would be reached in the Treaty of Tordesillas between both emerging maritime powers.[64]

New World voyages and Treaty of Tordesillas

_02c.jpg.webp)

Seven months before the treaty of Alcaçovas, King John II of Aragon died, and his son Ferdinand II of Aragon, married to Isabella I of Castile, inherited the thrones of the Crown of Aragon. The two became known as the Catholic Monarchs, with their marriage a personal union that created a relationship between the Crown of Aragon and Castile, each with their own administrations, but ruled jointly by the two monarchs.[65]

Ferdinand and Isabella defeated the last Muslim king out of Granada in 1492 after a ten-year war. The Catholic Monarchs then negotiated with Christopher Columbus, a Genoese sailor attempting to reach Cipangu (Japan) by sailing west. Castile was already engaged in a race of exploration with Portugal to reach the Far East by sea when Columbus made his bold proposal to Isabella. In the Capitulations of Santa Fe, dated on 17 April 1492, Christopher Columbus obtained from the Catholic Monarchs his appointment as viceroy and governor in the lands already discovered[66] and that he might discover thenceforth;[67][68] thereby, it was the first document to establish an administrative organization in the Indies.[69] Columbus' discoveries began the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Spain's claim[70] to these lands was solidified by the Inter caetera papal bull dated 4 May 1493, and Dudum siquidem on 26 September 1493.

Since the Portuguese wanted to keep the line of demarcation of Alcaçovas running east and west along a latitude south of Cape Bojador, a compromise was worked out and incorporated in the Treaty of Tordesillas, dated on 7 June 1494, in which the world was split into two dividing Spanish and Portuguese claims. These actions gave Spain exclusive rights to establish colonies in all of the New World from north to south (later with the exception of Brazil, which Portuguese commander Pedro Alvares Cabral encountered in 1500), as well as the easternmost parts of Asia. The Treaty of Tordesillas was confirmed by Pope Julius II in the bull Ea quae pro bono pacis on 24 January 1506.[71]

The Treaty of Tordesillas[72] and the treaty of Cintra (18 September 1509)[73] established the limits of the Kingdom of Fez for Portugal, and the Castilian expansion was allowed outside these limits, beginning with the conquest of Melilla in 1497.[lower-alpha 11]

Papal bulls and the Americas

Unlike the crown of Portugal, Spain had not sought papal authorization for its explorations, but with Christopher Columbus's voyage in 1492, the crown sought papal confirmation of their title to the new lands.[75] Since the defense of Catholicism and propagation of the faith was the papacy's primary responsibility, there were a number of papal bulls promulgated that affected the powers of the crowns of Spain and Portugal in the religious sphere. Converting the inhabitants of in the newly discovered lands was entrusted by the papacy to the rulers of Portugal and Spain, through a series of papal actions. The Patronato real, or power of royal patronage for ecclesiastical positions had precedents in Iberia during the reconquest. In 1493 Pope Alexander, from the Iberian Kingdom of Valencia, issued a series of bulls. The papal bull of Inter caetera vested the government and jurisdiction of newly found lands in the kings of Castile and León and their successors. Eximiae devotionis granted the Catholic monarchs and their successors the same rights that the papacy had granted Portugal, in particular the right of presentation of candidates for ecclesiastical positions in the newly discovered territories.[76]

According to the Concord of Segovia of 1475, Ferdinand was mentioned in the bulls as king of Castile, and upon his death the title of the Indies was to be incorporated into the Crown of Castile.[77] The territories were incorporated by the Catholic Monarchs as jointly held assets.[78]

In the Treaty of Villafáfila of 1506, Ferdinand renounced not only the government of Castile in favor of his son-in-law Philip I of Castile but also the lordship of the Indies, withholding a half of the income of the kingdoms of the Indies.[80] Joanna of Castile and Philip immediately added to their titles the kingdoms of Indies, Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea. But the Treaty of Villafáfila did not hold for long because of the death of Philip; Ferdinand returned as regent of Castile and as "lord the Indies".[77]

According to the domain granted by papal bulls and the wills of queen Isabella of Castile in 1504 and King Ferdinand of Aragon in 1516, such property became held by the Crown of Castile. This arrangement was ratified by successive monarchs, beginning with Charles I in 1519[78] in a decree that spelled out the juridical status of the new overseas territories.[81]

The lordship of the discovered territories conveyed by papal bulls was private to the kings of Castile and León. The political condition of the Indies were to transform from "Lordship" of the Catholic Monarchs to "Kingdoms" for the heirs of Castile. Although the Alexandrine Bulls gave full, free and omnipotent power to the Catholic Monarchs,[82] they did not rule them as a private property but as a public property through the public bodies and authorities from Castile,[83] and when those territories were incorporated into the Crown of Castile the royal power was subject to the laws of Castile.[82]

The crown was the guardian of levies for the support of the Catholic Church, in particular the tithe, which was levied on the products of agriculture and ranching. In general, Indians were exempt from the tithe. Although the crown received these revenues, they were to be used for the direct support of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and pious establishments, so that the crown itself did not benefit financially from this income. The crown's obligation to support the Church sometimes resulted in funds from the royal treasury being transferred to the Church when the tithes fell short of paying ecclesiastical expenses.[84]

In New Spain, the Franciscan Bishop of Mexico Juan de Zumárraga and the first viceroy Don Antonio de Mendoza established an institution in 1536 to train natives for ordination to the priesthood, the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco. The experiment was deemed a failure, with the natives considered too new in the faith to be ordained. Pope Paul III did issue a bull, Sublimis Deus (1537), declaring that natives were capable of becoming Christians, but Mexican (1555) and Peruvian (1567–68) provincial councils banned natives from ordination.[76]

North American exploration

During the 1500s, the Spanish began to explore and colonize North America. They were looking for gold in native kingdoms. By 1511 there were rumours of undiscovered lands to the northwest of Hispaniola. Juan Ponce de León equipped three ships with at least 200 men at his own expense and set out from Puerto Rico on 4 March 1513 to Florida and surrounding coastal area. Another early motive was the search for the Seven Cities of Gold, or "Cibola", rumoured to have been built by Native Americans somewhere in the desert Southwest. In 1536 Francisco de Ulloa, the first documented European to reach the Colorado River, sailed up the Gulf of California and a short distance into the river's delta.

In the year 1524 the Portuguese Estevão Gomes, who'd sailed in Ferdinand Magellan's fleet, explored Nova Scotia, sailing South through Maine, where he entered New York Harbor, the Hudson River and eventually reached Florida in August 1525.

The Spaniard Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca was the leader of the Narváez expedition of 600 men, that between 1527 and 1535 explored the mainland of North America. From Tampa Bay, Florida on 15 April 1528, they marched through Florida. Traveling mostly on foot, they crossed Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, and Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León and Coahuila. After several months of fighting native inhabitants through wilderness and swamp, the party reached Apalachee Bay with 242 men. They believed they were near other Spaniards in Mexico, but there was in fact 1500 miles of coast between them. They followed the coast westward, until they reached the mouth of the Mississippi River near to Galveston Island. Later they were enslaved for a few years by various Native American tribes of the upper Gulf Coast. They continued through Coahuila and Nueva Vizcaya; then down the Gulf of California coast to what is now Sinaloa, Mexico, over a period of roughly eight years. They spent years enslaved by the Ananarivo of the Louisiana Gulf Islands. Later they were enslaved by the Hans, the Capoques and others. In 1534 they escaped into the American interior, contacting other Native American tribes along the way. Only four men, Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, and an enslaved Moroccan Berber named Estevanico, survived and escaped to reach Mexico City. In 1539, Estevanico was one of four men who accompanied Marcos de Niza as a guide in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, preceding Coronado. When the others were struck ill, Estevanico continued alone, opening up what is now New Mexico and Arizona. He was killed at the Zuni village of Hawikuh in present-day New Mexico.

The viceroy of New Spain Antonio de Mendoza, for who is named the Codex Mendoza, commissioned several expeditions to explore and establish settlements in the northern lands of New Spain in 1540–42. Francisco Vásquez de Coronado reached Quivira in central Kansas. Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo explored the western coastline of Alta California in 1542–43.

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado's 1540–42 expedition began as a search for the fabled Cities of Gold, but after learning from natives in New Mexico of a large river to the west, he sent García López de Cárdenas to lead a small contingent to find it. With the guidance of Hopi Indians, Cárdenas and his men became the first outsiders to see the Grand Canyon. However, Cárdenas was reportedly unimpressed with the canyon, assuming the width of the Colorado River at six feet (1.8 m) and estimating 300-foot (91 m)-tall rock formations to be the size of a man. After unsuccessfully attempting to descend to the river, they left the area, defeated by the difficult terrain and torrid weather.

In 1540, Hernando de Alarcón and his fleet reached the mouth of the Colorado River, intending to provide additional supplies to Coronado's expedition. Alarcón may have sailed the Colorado as far upstream as the present-day California–Arizona border. However, Coronado never reached the Gulf of California, and Alarcón eventually gave up and left. Melchior Díaz reached the delta in the same year, intending to establish contact with Alarcón, but the latter was already gone by the time of Díaz's arrival. Díaz named the Colorado River Rio del Tizon, while the name Colorado ("Red River") was first applied to a tributary of the Gila River.

In 1540, expeditions under Hernando de Alarcón and Melchior Díaz visited the area of Yuma and immediately saw the natural crossing of the Colorado River from Mexico to California by land, as an ideal spot for a city, as the Colorado River narrows to slightly under 1000 feet wide in one small point. Later military expedition that crossed the Colorado River at the Yuma Crossing include Juan Bautista de Anza (1774).

In 1541, Hernando de Soto became the first explorer to cross the Mississippi River. During this expedition, the Spanish fought Utina tribesmen in Florida, Chickasaws in Mississippi, the Coosa chiefdom in present-day Georgia, and Chief Tuskaloosa at the Battle of Mabila in present-day Alabama. Spanish losses at Mabila were 22 killed and 148 wounded, while 2,500 Native Americans were killed, making it the bloodiest battle ever fought between Native American tribes and Europeans in the present-day United States.

In 1565, the Spanish, led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, established St. Augustine in Florida. Subsequently, they launched an attack on Fort Caroline in French Florida, resulting in the massacre of 142 French Huguenots. The surviving French colonists fled on ships, which wrecked in a storm at the Matanzas River. The Spanish captured them, killing 210 Huguenots in the Massacre at Matanzas Inlet. St. Augustine quickly became a strategic defensive base for the Spanish ships full of gold and silver being sent to Spain from its New World dominions.

The Chamuscado and Rodríguez Expedition explored New Mexico in 1581–82. They explored a part of the route visited by Coronado in New Mexico and other parts in the southwestern United States between 1540 and 1542.

The viceroy of New Spain Don Diego García Sarmiento sent another expedition in 1648 to explore, conquer and colonize the Californias.

First settlements in the Americas

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

With the Capitulations of Santa Fe, the Crown of Castile granted expansive power to Christopher Columbus, including exploration, settlement, political power, and revenues, with sovereignty reserved to the Crown. The first voyage established sovereignty for the crown, and the crown acted on the assumption that Columbus's grandiose assessment of what he found was true, so Spain negotiated the Treaty of Tordesillas with Portugal to protect their territory on the Spanish side of the line. The crown fairly quickly reassessed its relationship with Columbus and moved to assert more direct crown control over the territory and extinguish his privileges. With that lesson learned, the crown was far more prudent in the specifying the terms of exploration, conquest, and settlement in new areas.

The pattern in the Caribbean that played out over the larger Spanish Indies was exploration of an unknown area and claim of sovereignty for the crown; conquest of indigenous peoples or assumption of control without direct violence; settlement by Spaniards who were awarded the labour of indigenous people via the encomienda; and the existing settlements becoming the launch point for further exploration, conquest, and settlement, followed by the establishment institutions with officials appointed by the crown. The patterns set in the Caribbean were replicated throughout the expanding Spanish sphere, so although the importance of the Caribbean quickly faded after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, many of those participating in those conquests had started their exploits in the Caribbean.[85]

The first permanent European settlements in the New World were established in the Caribbean, initially on the island of Hispaniola, later Cuba, Jamaica and Puerto Rico. Columbus established the fort of La Navidad in present-day Haiti; it was later destroyed by the Taínos and the Spanish garrison was wiped out. The colonists, many of whom were criminals banished from Spain, quickly grew disillusioned due to the hardships, disease, and poverty they experienced. Frictions arose both among themselves and with the local tribesmen.

As a Genoese with connections to Portugal, Columbus considered settlement to be on the pattern of trading forts and factories, with salaried employees to trade with locals and to identify exploitable resources.[86] However, Spanish settlement in the New World was based on a pattern of a large, permanent settlements with the entire complex of institutions and material life to replicate Castilian life in a different venue. Columbus's second voyage in 1493 had a large contingent of settlers and goods to accomplish that.[87] On Hispaniola, the city of Santo Domingo was founded in 1496 by Christopher Columbus's brother Bartholomew Columbus and became a stone-built, permanent city. Non-Castilians, such as Catalans and Aragonese, were often prohibited from migrating to the New World.

The Spanish subjugated the native populations of Puerto Rico in 1508–09 and Jamaica in 1510. In the spring of 1511, a Taíno uprising erupted in Puerto Rico under the leadership of the main tribal leader Agüeybaná II. Among their first victims were Ponce de León's former lieutenant governor Cristóbal de Sotomayor and his nephew Diego. The town of Sotomayor was torched, and all its inhabitants were killed, except for Juan González, who carried a warning to other inhabitants and Ponce de León at Caparra. In all, some 80 Spaniards were killed, and approximately 11,000 natives rose in revolt before the rebellion was eventually crushed by Ponce de León.[88] The deaths of Spanish residents at the hands of Puerto Rican rebels prompted Queen Juana in Spain to issue a decree on 3 June of the same year, authorizing Spaniards to wage war against the Taínos anywhere in the New World and to treat any prisoners they capture as slaves.[88] In November 1511, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar departed from Salvatierra de la Sábana (present-day Les Cayes) with 330 Spaniards and some Taíno auxiliaries aboard four ships. They were in pursuit of the Taíno chieftain Hatuey, who had fled west and reestablished himself on Cuba after escaping the 1503 Jaragua massacre in Hispaniola led by de Ovando, during which 7,000 Taínos were killed. Hatuey was defeated and burned at the stake.[88] By early 1512, Velázquez established the first official Spanish settlement on Cuba: Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Baracoa.

Some scholars have described the initial period of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, from 1492 until the mid 16th century, as the largest case of genocide in history, with millions of indigenous peoples dying from imported Eurasia diseases that travelled more quickly than the Spanish conquerors.[89] Additionally, large-scale massacres perpetrated by the Spanish against indigenous populations further contributed to the death toll. Other international genocide scholars, like Alex Alvarez in his book, "Native America and the Question of Genocide," demonstrate that the deaths of Indigenous Americans due to disease spread by contact with Europeans does not constitute genocide, as the intent to exterminate is necessary for genocide to occur.[90] The death toll is estimated as high as 70 million out of a population of 80 million during this period. Diseases killed between 50% and 95% of the indigenous population.[89] Some scholars attribute the vast majority of indigenous deaths due to the low immunological capacity of native populations to resist exogenous diseases.[91]

Assertion of Crown control in the Americas

Although Columbus staunchly asserted and believed that the lands he encountered were in Asia, the paucity of material wealth and the relative lack of complexity of indigenous society meant that the Crown of Castile initially was not concerned with the extensive powers granted Columbus. As the Caribbean became a draw for Spanish settlement and as Columbus and his extended Genoese family failed to be recognized as officials worthy of the titles they held, there was unrest among Spanish settlers. The crown began to curtail the expansive powers that they had granted Columbus, first by appointment of royal governors and then a high court or Audiencia in 1511.

Columbus encountered the mainland in 1498,[92] and the Catholic Monarchs learned of his discovery in May 1499. Taking advantage of a revolt against Columbus in Hispaniola, they appointed Francisco de Bobadilla as governor of the Indies with civil and criminal jurisdiction over the lands discovered by Columbus. Bobadilla, however, was soon replaced by Frey Nicolás de Ovando in September 1501.[93] Henceforth, the Crown would authorize to individuals voyages to discover territories in the Indies only with previous royal license,[92] and after 1503 the monopoly of the Crown was assured by the establishment of the Casa de Contratación (House of Trade) at Seville. The successors of Columbus, however, litigated against the Crown until 1536[94] for the fulfillment of the Capitulations of Santa Fe in the pleitos colombinos.

In metropolitan Spain, the direction of the Americas was taken over by the Bishop Fonseca[95] between 1493 and 1516,[96] and again between 1518 and 1524, after a brief period of rule by Jean le Sauvage.[97] After 1504 the figure of the secretary was added, so between 1504 and 1507 Gaspar de Gricio took charge,[98] between 1508 and 1518 Lope de Conchillos followed him,[99] and from 1519, Francisco de los Cobos.[100]

In 1511, the Junta of The Indies was constituted as a standing committee belonging to the Council of Castile to address issues of the Indies,[101] and this junta constituted the origin of the Council of the Indies, established in 1524.[102] That same year, the crown established a permanent high court, or audiencia, in the most important city at the time, Santo Domingo, on the island of Hispaniola (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Now oversight of the Indies was based both in Castile and with officials of the new royal court in the colony. As new areas were conquered and significant Spanish settlements were established, likewise other audiencias were established.

Following the settlement of Hispaniola, Europeans began searching elsewhere to begin new settlements, since there was little apparent wealth and the numbers of indigenous were declining. Those from the less prosperous Hispaniola were eager to search for new success in a new settlement. From there Juan Ponce de León conquered Puerto Rico (1508) and Diego Velázquez took Cuba.

In 1508, the Board of Navigators met in Burgos and concurred on the need to establish settlements on the mainland, a project entrusted to Alonso de Ojeda and Diego de Nicuesa as governors. They were subordinated to the governor of Hispaniola,[103] the newly appointed Diego Columbus,[104] with the same legal authority as Ovando.[105]

The first settlement on the mainland was Santa María la Antigua del Darién in Castilla de Oro (now Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Panama and Colombia), settled by Vasco Núñez de Balboa in 1510. In 1513, Balboa crossed the Isthmus of Panama, and led the first European expedition to see the Pacific Ocean from the West coast of the New World. In an action with enduring historical import, Balboa claimed the Pacific Ocean and all the lands adjoining it for the Spanish Crown.[106]

The judgment of Seville of May 1511 recognized the viceregal title to Diego Columbus, but limited it to Hispaniola and to the islands discovered by his father, Christopher Columbus;[107] his power was nevertheless limited by royal officers and magistrates[108] constituting a dual regime of government.[109] The crown separated the territories of the mainland, designated as Castilla de Oro,[110] from the viceroy of Hispaniola, establishing Pedrarias Dávila as General Lieutenant in 1513[111] with functions similar to those of a viceroy, while Balboa remained but was subordinated as governor of Panama and Coiba on the Pacific Coast;[112] after his death, they returned to Castilla de Oro. The territory of Castilla de Oro did not include Veragua (which was comprised approximately between the Chagres River and cape Gracias a Dios[113]), as it was subject to a lawsuit between the Crown and Diego Columbus, or the region farther north, towards the Yucatán peninsula, explored by Yáñez Pinzón and Solís in 1508–1509, due to its remoteness.[114] The conflicts of the viceroy Columbus with the royal officers and with the Audiencia, created in Santo Domingo in 1511,[115] caused his return to the Peninsula in 1515.

Conquest of the Aztec Empire

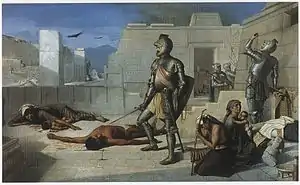

Defying the opposition of Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, the governor of Hispaniola, Hernán Cortés organized an expedition of 550 conquistadors and sailed for the coast of Mexico in March 1519. The Castilians defeated a 10,000-strong Chontal Mayan army at Potonchán on 24 March and emerged triumphant against a larger force of 40,000 Mayans three days later. On 2 September, 360 Castilians and 2,300 Totonac Indian allies defeated a 20,000-strong Tlaxcalan army. Three days later, a 50,000-strong Otomi-Tlaxcalan force was defeated by Spanish arquebusier and cannon fire, and a Castilian cavalry charge. Thousands of Tlaxcalans joined the invaders against their Aztec rulers. Cortés's forces sacked the city of Cholula, massacring 6,000 inhabitants,[116] and later entered Emperor Moctezuma II's capital, Tenochtitlan, on 8 November. Velázquez sent a force led by Pánfilo de Narváez to punish the insubordinate Cortés for his unauthorized invasion of Mexico, but they were defeated at the Battle of Cempoala on 29 May 1520. Narváez was wounded and captured and 17 of his troops were killed; the rest joined Cortés.[116] The conquistadors now totaled 1,500 Spaniards, 90 horses, and 30 cannons. Meanwhile, Pedro de Alvarado triggered a Mexica uprising following the Massacre in the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan, during which 400 Mexica nobles and 2,000 onlookers were hacked and bludgeoned to death. The Castilians were driven out of the Aztec capital, suffering 450 dead,[117] and losing all of their gold and guns during La Noche Triste.

On 8 July 1520, at Otumba, the Castilians and their allies, without artillery or arquebusiers, repelled 100,000 Aztecs armed with obsidian-bladed swords. In August, 500 Castilians and 40,000 Tlaxcalans conquered the hilltop town of Tepeaca,[117] an Aztec ally. The town and its surrounding area were ravaged, with most citizens either branded on the face with the letter "G" (for guerra) and enslaved by the Spanish, or sacrificed and eaten by the Tlaxcaltecans.[117] By the spring of 1521, Cortés had formed a new invasion force. The new emperor, Cuauhtémoc, defended Tenochtitlan with 100,000 warriors armed with slings, bows, and obsidian swords. From 21 May to 1 June, the Spanish-Tlaxcalan forces swept the lake and ravaged the countryside. The first military encounter occurred after an advance along the causeway at Tlacopan by the armies of Alvarado and Cristóbal de Olid. While fighting on the causeway, the Spanish and their allies came under attack from both sides by Aztecs firing arrows from canoes. Thirteen Spanish brigantines sank 300 out of 400 enemy war canoes sent against them. The Aztecs tried to damage the Spanish vessels by hiding spears beneath the shallow water. The attackers breached the city and engaged in fighting with the Aztec defenders in the streets. The Aztecs defeated the Spanish-Tlaxcalan forces at the Battle of Colhuacatonco on 30 June. Following their victory, 53 Spanish prisoners were paraded to the tops of Tlatelolco's highest pyramids and publicly sacrificed.[118] In late July, the attackers resumed their assaults, resulting in the massacre of 800 Aztec civilians. By 29 July, the Spanish had reached Tlatelolco's center, raising their new flag atop the city's twin towers. Having exhausted their gunpowder, they attempted a catapult breach but failed. On 3 August, 12,000 more civilians were killed in another city section.[119] Alvarado's destruction of the aqueducts forced the Aztecs to drink from the lake, causing disease and thousands of deaths. Another major assault occurred on 12 August, during which many thousands of non-combatants were massacred in their shelters.[120] The following day, the city fell, and Cuauhtémoc was captured (and hanged in 1525). At least 100,000 people died,[120] and the city was left in ruins, reduced to rubble, and completely destroyed. After the Fall of Tenochtitlan, Cortés directed the burning of Aztec books and records, destroyed monuments, removed idols from temples, and purged the sites of sacrificial remnants to prepare the locations for Catholic worship.

The Spanish Habsburgs (1516–1700)

As a result of the marriage politics of the Catholic Monarchs (in Spanish, Reyes Católicos), their Habsburg grandson Charles inherited the Castilian empire in the Americas and the possessions of the Crown of Aragon in the Mediterranean (including all of south Italy), lands in Germany, the Low Countries, Franche-Comté, and Austria, starting the rule of the Spanish Habsburgs. The Austrian hereditary Habsburg domains were transferred to Ferdinand, the Emperor's brother, whereas Spain and the remaining possessions were inherited by Charles's son, Philip II of Spain, at the abdication of the former in 1556.

The Habsburgs pursued several goals:

- Undermining the power of France and containing it in its eastern borders

- Defending Europe against Islam, notably the Ottoman Empire in the Ottoman–Habsburg wars

- Maintaining Habsburg hegemony in the Holy Roman Empire and defending the Roman Catholic Church against the Protestant Reformation

- Spreading (Catholic) Christianity to the unconverted indigenous of the New World and the Philippines

- Exploiting the resources of the Americas (gold, silver, sugar) and trading with Asia (porcelain, spices, silk)

- Excluding other European powers from the possessions it claimed in the New World

"I learnt a proverb here", said a French traveler in 1603: "Everything is dear in Spain except silver".[121] The problems caused by inflation were discussed by scholars at the School of Salamanca and the arbitristas. The natural resource abundance provoked a decline in entrepreneurship as profits from resource extraction are less risky.[122] The wealthy preferred to invest their fortunes in public debt (juros). The Habsburg dynasty spent the Castilian and American riches in wars across Europe on behalf of Habsburg interests, and declared moratoriums (bankruptcies) on their debt payments several times. These burdens led to a number of revolts across the Spanish Habsburg's domains, including their Spanish kingdoms.

Philip II of Spain (r. 1556–98) conquered the Philippines in 1565, making him ruler of the first true globe-spanning empire.[123] His victory in the War of the Portuguese Succession led to the annexation of Portugal in 1580, effectively integrating its overseas empire—encompassing coastal Brazil and African and Indian coastal enclaves—into Spain's domain.[123] His reign was marked by additional conflicts, including the Eighty Years' War, and the Anglo-Spanish War, which resulted in 88,285 English deaths from all war-related causes and the worldwide capture of over 1,000 Spanish ships by English pirates.[124] The attempted invasion of England by the Spanish Armada in 1588 marked the first southern European threat to the British Isles since Roman times. Philip also became embroiled in conflicts with the Ottoman Empire, and in 1571, his galley fleet achieved a significant victory by destroying Ottoman galleys and killing 40,000 Muslims at the Battle of Lepanto, but the Ottomans quickly rebuilt their Mediterranean fleet and forced a truce on Philip in 1578.[123]

The Franco-Spanish War (1635–1659), which resulted in 300,000 French casualties,[124] marked the beginning of Spain's decline in Western Europe. By the mid-17th century, Spain's global empire burdened its economic, administrative, and military resources. Over the preceding century, Spanish troops had fought in France, Germany, and the Netherlands, suffering heavy casualties.[125] Despite its vast holdings, Spain's military lacked essential modernization and heavily relied on foreign suppliers.[125] Nevertheless, Spain possessed abundant bullion from the Americas, which played a crucial role in both sustaining its military endeavors and meeting the needs of its civilian population. During this period, Spain displayed limited military interest in its overseas colonies. The Criollo elites and mestizo and mulatto militia provided only minimal protection, often assisted by more influential allies with vested interests in maintaining the balance of power and safeguarding the Spanish Empire from falling into enemy hands.[125]

Imperial economic policy

The Spanish Empire benefited from favorable factor endowments from its overseas possessions with their large, exploitable indigenous populations and rich mining areas.[126] Thus the crown attempted to create and maintain a classic closed mercantile system, warding off competitors and keeping wealth within the empire, specifically within the Crown of Castile. While in theory the Habsburgs were committed to maintaining a state monopoly, the reality was that the empire was a porous economic realm with widespread smuggling. In the 16th and 17th centuries under the Habsburgs, Spain's economic conditions gradually declined, especially in regards to the industrial development of its French, Dutch, and English rivals. Many of the goods being exported to the Empire originated from manufacturers in northwest Europe rather than in Spain. Illicit commercial activities became a part of the Empire's administrative structure. Supported by large flows of silver from the Americas, trade prohibited by Spanish mercantilist restrictions flourished as it provided a source of income to both crown officials and private merchants.[127] The local administrative structure in Buenos Aires, for example, was established through its oversight of both legal and illegal commerce.[128] The crown's pursuit of wars to maintain and expand territory, defend the Catholic faith, stamp out Protestantism, and beat back the Ottoman Turkish strength outstripped its ability to pay for it all, despite the huge production of silver in Peru and New Spain. Most of that flow paid mercenary soldiers in the European religious wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and paid foreign merchants for the consumer goods manufactured in northern Europe. Paradoxically, the wealth of the Indies impoverished Spain and enriched northern Europe, a course the Bourbon monarchs would later attempt to reverse in the eighteenth century.[129]

This was well acknowledged in Spain, with writers on political economy, the arbitristas, sending the crown lengthy analyses in the form of "memorials, of the perceived problems and with proposed solutions."[130][131] According to these thinkers, "Royal expenditure must be regulated, the sale of office halted, the growth of the church checked. The tax system must be overhauled, special concessions be made to agricultural laborers, rivers be made navigable and dry lands irrigated. In this way alone could Castile's productivity increase, its commerce restored, and its humiliating dependence on foreigners, on the Dutch and the Genoese, be brought to an end."[132]

Since the early days of the Caribbean and conquest era, the crown attempted to control trade between Spain and the Indies with restrictive policies enforced by the House of Trade (est. 1503) in Seville. Shipping was through particular ports in Castile: Seville, and subsequently Cádiz, Spanish America: Veracruz, Acapulco, Havana, Cartagena de Indias, and Callao/Lima, and the Philippines: Manila. There were very few Spanish settlers in the Indies in the very early period and Spain could supply sufficient goods to them. But as the Aztec and Inca empires were conquered in the early sixteenth century, and large deposits of silver found in both Mexico and Peru, Spanish immigration increased and the demand for goods rose far beyond Spain's ability to supply it. Since Spain had little capital to invest in the expanding trade and no significant commercial group, bankers and commercial houses in Genoa, Germany, the Netherlands, France, and England supplied both investment capital and goods in a supposedly closed system. Even in the sixteenth century, Spain recognized that the idealized closed system did not function in reality. Since the crown did not alter its restrictive structure or advocate fiscal prudence, despite the pleas of the arbitristas, the Indies trade remained nominally in the hands of Spain, but in fact enriched the other European countries.

The crown established the system of treasure fleets (Spanish: flota) to protect the conveyance of silver to Seville (later Cádiz). Produced in other European countries, Sevillian merchants conveyed consumer goods that were registered and taxed by the House of Trade, and then sent to the Indies. Other European commercial interests came to dominate supply, with Spanish merchant houses and their guilds (consulados) in both Spain and the Indies acting as mere middlemen, reaping a slice of the profits. However, those profits did not promote a manufacturing sector in Spain's economic development, and its economy continued to be based in agriculture. The wealth of the Indies led to prosperity in northern Europe, particularly in the Netherlands and England, which were both Protestant. As Spain's power weakened in the seventeenth century, England, the Netherlands, and the French took advantage overseas by seizing islands in the Caribbean, which became bases for a burgeoning contraband trade in Spanish America. Crown officials, who were supposed to suppress contraband trade, were quite often in cahoots with the foreigners, since it was a source of personal enrichment. In Spain, the crown itself participated in collusion with foreign merchant houses, since they paid fines "meant to establish a compensation to the state for losses through fraud." It became a calculated risk for merchant houses doing business, and for the crown it gained income that would have otherwise been lost. Foreign merchants were part of the supposed monopoly system of trade. The transfer of the House of Trade from Seville to Cádiz meant foreign merchant houses had even easier access to the Spanish trade.[134]

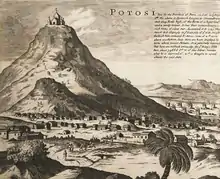

The Spanish imperial economy's major global impact was silver mining. The mines in Peru and Mexico were in the hands of a few elite mining entrepreneurs with access to capital and a stomach for the risk that mining entailed. They operated under a system of royal licensing, since the crown held the rights to subsoil wealth. Mining entrepreneurs assumed all the risk of the enterprise, while the crown gained a 20% slice of the profits, the royal fifth ("quinto real"). Further adding to the crown's revenues in mining was that it held a monopoly on the mercury supply, used for separating pure silver from silver ore in the patio process. The crown kept the price high, thereby depressing the volume of silver production.[135] Protecting its flow from Mexico and Peru as it transited to ports for shipment to Spain resulted early on in a convoy system (the flota) sailing twice a year. Its success can be judged by the fact that the silver fleet was captured only once, in 1628 by Dutch privateer Piet Hein. That loss resulted in the bankruptcy of the Spanish crown and an extended period of economic depression in Spain.[136]

One practice the Spanish used to gather workers for the mines was called repartimiento. This was a rotational forced labor system where indigenous pueblos were obligated to send laborers to work in Spanish mines and plantations for a set number of days out of the year. Repartimiento was not implemented to replace slave labor, but instead existed alongside free wage labor, slavery, and indentured labor. It was, however, a way for the Spanish to procure cheap labor, thus boosting the mining-driven economy. It is important to note that the men who worked as repartimiento laborers were not always resistant to the practice. Some were drawn to the labor as a way to supplement the wages they earned cultivating fields so as to support their families and, of course, pay tributes. At first, a Spaniard could get repartimiento laborers to work for them with permission from a crown official, such as a viceroy, only on the basis that this labor was absolutely necessary to provide the country with important resources. This condition became laxer as the years went on, and various enterprises had repartimiento laborers who would work in dangerous conditions for long hours and low wages.[137]

During the Bourbon era, economic reforms sought to reverse the pattern that left Spain impoverished with no manufacturing sector and its colonies' need for manufactured goods supplied by other nations. It attempted to establish a closed trading system, but it was hampered by the terms of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. The treaty ending the War of the Spanish Succession, with a victory for the Bourbon French candidate for the throne, had a provision for British merchants to legally sell slaves with a license (Asiento de Negros) slaves to Spanish America. The provision undermined the possibility of a revamped Spanish monopoly system. The merchants also used the opportunity to engage in contraband trade of their manufactured goods. Crown policy sought to make legal trade more appealing than contraband by instituting free commerce (comercio libre) in 1778, whereby Spanish American ports could trade with each other, and they could trade with any port in Spain. It was aimed at revamping a closed Spanish system and outflanking the increasingly powerful British. Silver production revived in the eighteenth century, with production far surpassing the earlier output. The crown reduced the taxes on mercury, meaning that a greater volume of pure silver could be refined. Silver mining absorbed most of the available capital in Mexico and Peru, and the crown emphasized the production of precious metals, which were sent to Spain. There was some economic development in the Indies to supply food, but a diversified economy did not emerge.[135] The economic reforms of the Bourbon era both shaped and were themselves impacted by geopolitical developments in Europe. The Bourbon Reforms arose out of the War of the Spanish Succession. In turn, the crown's attempt to tighten its control over its colonial markets in the Americas led to further conflict with other European powers who were vying for access to them. After a sparking a series of skirmishes throughout the 1700s over its stricter policies, Spain's reformed trade system led to war with Britain in 1796.[138] In the Americas, meanwhile, economic policies enacted under the Bourbons had different impacts in different regions. On one hand, silver production in New Spain greatly increased and led to economic growth. But much of the profits of the revitalized mining sector went to mining elites and state officials, while in rural areas of New Spain conditions for rural workers deteriorated, contributing to social unrest that would impact subsequent revolts.[139]

Pacific exploration and trade

In 1525, King Charles I of Spain ordered an expedition led by friar García Jofre de Loaísa to go to Asia by the western route to colonize the Maluku Islands (known as Spice Islands, now part of Indonesia), thus crossing first the Atlantic and then the Pacific oceans. Ruy López de Villalobos sailed to the Philippines in 1542–43. From 1546 to 1547 Francis Xavier worked in Maluku among the peoples of Ambon Island, Ternate, and Morotai, and laid the foundations for the Christian religion there.

In 1564, Miguel López de Legazpi was commissioned by the viceroy of New Spain, Luis de Velasco, to explore the Maluku Islands where Magellan and Ruy López de Villalobos had landed in 1521 and 1543, respectively. The expedition was ordered by King Philip II of Spain, after whom the Philippines had earlier been named by Villalobos. Legazpi established settlements in the East Indies and the Pacific Islands in 1565. He was the first governor-general of the Spanish East Indies. After obtaining peace with various indigenous tribes, López de Legazpi made Manila the capital in 1571.

The Spanish settled and took control of Tidore in 1603 to trade spices and counter Dutch encroachment in the archipelago of Maluku. The Spanish presence lasted until 1663, when the settlers and military were moved back to the Philippines. Part of the Ternatean population chose to leave with the Spanish, settling near Manila in what later became the municipality of Ternate.

Spanish galleons travelled across the Pacific Ocean annually between Acapulco in Mexico and Manila, and from there the primary Asian destination for silver from the Americas was China.[140]

In 1542, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo traversed the coast of California and named many of its features. In 1601, Sebastián Vizcaíno mapped the coastline in detail and gave new names to many features. Martín de Aguilar, lost from the expedition led by Sebastián Vizcaíno, explored the Pacific coast as far north as Coos Bay in present-day Oregon.

Since the 1549 arrival to Kagoshima (Kyushu) of a group of Jesuits with St. Francis Xavier missionary and Portuguese traders, Spain was interested in Japan. In this first group of Jesuit missionaries were included Spaniards Cosme de Torres and Juan Fernández.

In 1611, Sebastián Vizcaíno surveyed the east coast of Japan and from the year of 1611 to 1614 he was ambassador of King Philip III in Japan returning to Acapulco in the year of 1614. In 1608, he was sent to search for two mythical islands called Rico de Oro (island of gold) and Rico de Plata (island of silver).

Spain expanded its Pacific empire in 1668 when Jesuit missionary Diego Luis de San Vitores established a mission on Guam. San Vitores was killed by the native Chamorros in 1672, sparking the Spanish-Chamorro Wars.

The Spanish Bourbons (1700–1808)

With the 1700 death of the childless Charles II of Spain, the crown of Spain was contested in the War of the Spanish Succession. Under the Treaties of Utrecht (11 April 1713) ending the war, the French prince of the House of Bourbon, Philippe of Anjou, grandchild of Louis XIV of France, became King Philip V of Spain. He retained the Spanish overseas empire in the Americas and the Philippines. The settlement gave spoils to those who had backed a Habsburg for the Spanish monarchy, ceding European territory of the Spanish Netherlands, Naples, Milan, and Sardinia to Austria; Sicily and parts of Milan to the Duchy of Savoy, and Gibraltar and Menorca to the Kingdom of Great Britain. The treaty also granted British merchants the exclusive right to sell slaves in Spanish America for thirty years, the asiento de negros, as well as licensed voyages to ports in Spanish colonial dominions and openings.[141]

Spain's economic and demographic recovery had begun slowly in the last decades of the Habsburg reign, as was evident from the growth of its trading convoys and the much more rapid growth of illicit trade during the period. (This growth was slower than the growth of illicit trade by northern rivals in the empire's markets.) However, this recovery was not then translated into institutional improvement, rather the "proximate solutions to permanent problems."[142] This legacy of neglect was reflected in the early years of Bourbon rule in which the military was ill-advisedly pitched into battle in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1718–20). Spain was defeated in Italy by an alliance of Britain, France, Savoy, and Austria. Following the war, the new Bourbon monarchy took a much more cautious approach to international relations, relying on a family alliance with Bourbon France, and continuing to follow a program of institutional renewal.

The crown program to enact reforms that promoted administrative control and efficiency in the metropole to the detriment of interests in the colonies, undermined creole elites' loyalty to the crown. When French forces of Napoleon Bonaparte invaded the Iberian peninsula in 1808, Napoleon ousted the Spanish Bourbon monarchy, placing his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne. There was a crisis of legitimacy of crown rule in Spanish America, leading to the Spanish American wars of independence (1808–1826).

Bourbon reforms

The Spanish Bourbons' broadest intentions were to reorganize the institutions of empire to better administer it for the benefit of Spain and the crown. It sought to increase revenues and to assert greater crown control, including over the Catholic Church. Centralization of power (beginning with the Nueva Planta decrees against the realms of the Crown of Aragon) was to be for the benefit of the crown and the metropole and for the defense of its empire against foreign incursions.[143] From the viewpoint of Spain, the structures of colonial rule under the Habsburgs were no longer functioning to the benefit of Spain, with much wealth being retained in Spanish America and going to other European powers. The presence of other European powers in the Caribbean, with the English in Barbados (1627), St Kitts (1623–25), and Jamaica (1655); the Dutch in Curaçao, and the French in Saint Domingue (Haiti) (1697), Martinique, and Guadeloupe had broken the integrity of the closed Spanish mercantile system and established thriving sugar colonies.[144][74]

At the beginning of his reign, the first Spanish Bourbon, King Philip V, reorganized the government to strengthen the executive power of the monarch as was done in France, in place of the deliberative, Polysynodial System of Councils.[145]

Philip's government set up a ministry of the Navy and the Indies (1714) and established commercial companies, the Honduras Company (1714), a Caracas company; the Guipuzcoana Company (1728), and the most successful one, the Havana Company (1740).

In 1717–18, the structures for governing the Indies, the Consejo de Indias and the Casa de Contratación, which governed investments in the cumbersome Spanish treasure fleets, were transferred from Seville to Cádiz, where foreign merchant houses had easier access to the Indies trade.[146] Cádiz became the one port for all Indies trading (see flota system). Individual sailings at regular intervals were slow to displace the traditional armed convoys, but by the 1760s there were regular ships plying the Atlantic from Cádiz to Havana and Puerto Rico, and at longer intervals to the Río de la Plata, where an additional viceroyalty was created in 1776. The contraband trade that was the lifeblood of the Habsburg empire declined in proportion to registered shipping (a shipping registry having been established in 1735).

Two upheavals registered unease within Spanish America and at the same time demonstrated the renewed resiliency of the reformed system: the Tupac Amaru uprising in Peru in 1780 and the rebellion of the comuneros of New Granada, both in part reactions to tighter, more efficient control.

18th-century economic conditions

The 18th century was a century of prosperity for the overseas Spanish Empire as trade within grew steadily, particularly in the second half of the century, under the Bourbon reforms. Spain's victory in the Battle of Cartagena de Indias against a British expedition in the Caribbean port of Cartagena de Indias helped Spain secure its dominance of its possessions in the Americas until the 19th century. But different regions fared differently under Bourbon rule, and even while New Spain was particularly prosperous, it was also marked by steep wealth inequality. Silver production boomed in New Spain during the 18th century, with output more than tripling between the start of the century and the 1750s. The economy and the population both grew, both centered around Mexico City. But while mine owners and the crown benefited from the flourishing silver economy, most of the population in the rural Bajío faced rising land prices, falling wages. Eviction of many from their lands resulted.[139]

With a Bourbon monarchy came a repertory of Bourbon mercantilist ideas based on a centralized state, put into effect in the Americas slowly at first but with increasing momentum during the century. Shipping grew rapidly from the mid-1740s until the Seven Years' War (1756–63), reflecting in part the success of the Bourbons in bringing illicit trade under control. With the loosening of trade controls after the Seven Years' War, shipping trade within the empire once again began to expand, reaching an extraordinary rate of growth in the 1780s.

The end of Cádiz's monopoly of trade with the American colonies brought about very important changes, particularly a rebirth of Spanish manufactures. Most notable of those changes were both the beginning of Catalan participation in the Spanish slave trade, and the rapidly growing textile industry of Catalonia which by the mid-1780s saw the first signs of industrialization. This saw the emergence of a small, politically active commercial class in Barcelona. This isolated pocket of advanced economic development stood in stark contrast to the relative backwardness of most of the country. Most of the improvements were in and around some major coastal cities and the major islands such as Cuba, with its tobacco plantations, and a renewed growth of precious metals mining in South America.

Agricultural productivity remained low despite efforts to introduce new techniques to what was for the most part an uninterested, exploited peasant and laboring groups. Governments were inconsistent in their policies. Though there were substantial improvements by the late 18th century, Spain was still an economic backwater. Under the mercantile trading arrangements it had difficulty in providing the goods being demanded by the strongly growing markets of its empire, and providing adequate outlets for the return trade.

From an opposing point of view according to the "backwardness" mentioned above the naturalist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt traveled extensively throughout the Spanish Americas, exploring and describing it for the first time from a modern scientific point of view between 1799 and 1804. In his work Political essay on the kingdom of New Spain containing researches relative to the geography of Mexico he says that the Amerindians of New Spain were wealthier than any Russian or German peasant in Europe.[147] According to Humboldt, despite the fact that Indian farmers were poor, under Spanish rule they were free and slavery was non-existent, their conditions were much better than any other peasant or farmer in northern Europe.[148]

Humboldt also published a comparative analysis of bread and meat consumption in New Spain compared to other cities in Europe such as Paris. Mexico City consumed 189 pounds of meat per person per year, in comparison to 163 pounds consumed by the inhabitants of Paris, the Mexicans also consumed almost the same amount of bread as any European city, with 363 kilograms of bread per person per year in comparison to the 377 kilograms consumed in Paris. Caracas consumed seven times more meat per person than in Paris. Von Humboldt also said that the average income in that period was four times the European income and also that the cities of New Spain were richer than many European cities.[147]

Scientific investigations and expeditions

The Spanish American Enlightenment produced a huge body of information on Spain's overseas empire via scientific expeditions. The most famous traveler in Spanish America was Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt, whose travel writings, especially Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain and scientific observations remain important sources for the history of Spanish America. Humboldt's expedition was authorized by the crown, but was self-funded from his personal fortune. The Bourbon crown promoted state-funded scientific work prior to the famous Humboldt expedition. Eighteenth-century clerics contributed to the expansion of scientific knowledge.[149] These include José Antonio de Alzate y Ramírez,[150] and José Celestino Mutis.

The Spanish crown funded a number of important scientific expeditions: Botanical Expedition to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1777–78); Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada (1783–1816);[151] the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain (1787–1803);[152] which scholars are now examining afresh.[153] Although the crown funded a number of Spanish expeditions to the Pacific Northwest to bolster claims to territory, lengthy transatlantic and transpacific Malaspina-Bustamante Expedition was for scientific purposes. The crown also funded the Balmis Expedition in 1804 to vaccinate colonial populations against smallpox.

Much of the research done in the eighteenth century was never published or otherwise disseminated, in part due to budgetary constraints on the crown. Starting in the late twentieth century, research on the history of science in Spain and the Spanish empire has blossomed, with primary sources being published in scholarly editions or reissued, as well the publication of a considerable number of important scholarly studies.[154]

Contesting with other empires

In November 1717, Spain dispatched 18,000 soldiers to seize Sardinia while Austria was fully engaged in a war with the Ottoman Empire, and in July 1718, the Marquis de Lede led 30,000 troops, with 38 warships and 276 transports, to take control of Sicily, capturing Messina on 29 September. With naval support from Britain, the Austrians launched an effort to retake Sicily. However, their initial attempt ended in failure as a 21,000-strong Habsburg force was defeated by the Spaniards at the Battle of Francavilla, resulting in 3,100 Austrian casualties. In October 1719, the Austrians captured Messina but sustained 5,200 casualties among their 18,000 besieging troops. On 17 February 1720, Philip V of Spain renounced his claims to Italy, bringing an end to the war. Austria suffered approximately 15,000 killed or wounded, while Spain's losses numbered around 30,000.[124] In 1727, a dispute over Spanish possession of some Italian duchies led to an alliance between Britain and France against Spain. Gibraltar endured an unsuccessful siege from February to June 1727 by a Spanish force of 18,000, under the command of Count de las Torres. Subsequently, the conflict devolved into a war of words, culminating in a peace settlement in 1729.

Bourbon institutional reforms under Philip V bore fruit militarily when Spanish forces easily retook Naples and Sicily from the Austrians at the Battle of Bitonto in 1734 during the War of the Polish Succession, and during the War of Jenkins' Ear (1739–42) thwarted British efforts to capture the strategic cities of Cartagena de Indias, Santiago de Cuba and St. Augustine by defeating a British combined army and navy force, although Spain's invasion of Georgia also failed. The British suffered 25,000 dead or wounded and lost nearly 5,000 ships during the war.[155]

In 1742, the War of Jenkins' Ear merged with the larger War of the Austrian Succession, and King George's War in North America. The British, also occupied with France, were unable to capture Spanish convoys, and Spanish privateers captured British merchant shipping along the Triangle Trade routes and attacked the coast of North Carolina, levying tribute on the inhabitants. In Europe, Spain had been trying to divest Maria Theresa of the Duchy of Milan in northern Italy since 1741, but faced the opposition of Charles Emmanuel III of Sardinia, and warfare in northern Italy remained indecisive throughout the period up to 1746. By the 1748 Treaty of Aix-la-Chappelle, Spain gained (indirectly) Parma, Piacenza, and Guastalla in northern Italy. Spain was defeated during the invasion of Portugal and lost both Havana and Manila to British forces towards the end of the Seven Years' War (1756–63),[156] but it promptly recovered these losses and seized British forts in West Florida and the British naval base in the Bahamas during the American Revolutionary War (1775–83).

During most of the 18th century, Spanish privateers, particularly from Santo Domingo, were the scourge of the Antilles, with Dutch, British, French and Danish vessels as their prizes.[157]

Role in the American Revolution

Spain contributed to the independence of the Thirteen Colonies (which formed the United States) together with France. Spain and France were allies because of the Bourbon "Pacte de Famille" carried out by both countries against Britain.

Gibraltar was besieged for more than three years, but the British garrison stubbornly resisted and was resupplied twice: once after Admiral George Rodney's victory over Juan de Lángara in the 1780 Battle of Cape St. Vincent, and again by Admiral Richard Howe in 1782. Further Franco-Spanish efforts to capture Gibraltar were unsuccessful. One notable success took place on 5 February 1782, when the Spanish recaptured Minorca. Ambitious plans for an invasion of Britain in 1779 had to be abandoned. Admiral Luis de Córdova y Córdova captured two British convoys totaling seventy-nine ships, including a fleet of fifty-five merchantmen and frigates in the Action of 9 August 1780.