| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tessalon, others |

| Other names | Benzononatine; Egyt-13; KM-65[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682640 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Antitussives; Local anesthetics; Sodium channel blockers |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Onset of action | 15–20 minutes[3][4] |

| Elimination half-life | 1 hour[5] |

| Duration of action | 3–8 hours[3][4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.904 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C30H53NO11 |

| Molar mass | 603.750 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Benzonatate, sold under the brand name Tessalon among others, is a medication that is used for the symptomatic relief of cough.[6][7] A 2023 systematic review found that there is inadequate evidence to support the effectiveness and safety of benzonatate for cough and highlighted rising safety concerns.[8] Benzonatate is taken by mouth.[6][4] Effects generally begin within 20 minutes and last 3 to 8 hours.[6][3]

Side effects include sleepiness, dizziness, headache, upset stomach, skin rash, hallucinations, and allergic reactions.[6] Overdosage can result in serious adverse effects including seizures, irregular heartbeat, cardiac arrest, and death.[9][10] Overdose of only a small number of capsules can be fatal.[10] Chewing or sucking on the capsule, releasing the drug into the mouth, can also lead to laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and circulatory collapse.[6] It is unclear if use in pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe.[11] Benzonatate is a local anesthetic and voltage-gated sodium channel blocker.[5] It is theorized to work by inhibiting stretch receptors in the lungs, in turn suppressing the cough reflex in the brain.[5][6] Benzonatate is structurally related to other local anesthetics like procaine and tetracaine.[12][5]

Benzonatate was discovered in 1956 and was approved for medical use in the United States in 1958.[4][6] It is available as a generic medication.[9] Availability worldwide is limited, with the drug remaining marketed only in the United States and Mexico.[13][12][14] In 2020, it was the 157th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[15][16]

Medical uses

Cough

Benzonatate is a prescription non-opioid alternative for the symptomatic relief of cough.[6][9] It has been found to improve cough associated with a variety of respiratory conditions including asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, tuberculosis, pneumothorax, opioid-resistant cough in lung cancer, and emphysema.[6][4][17]

Benzonatate also reduces the consistency and volume of sputum production associated with cough in those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD).[4]

Compared to codeine, benzonatate has been reported to be more effective in reducing the frequency of induced cough in experiments.[6]

Benzonatate does not treat the underlying cause of the cough.[18]

According to a 2001 literature review, more than 29 clinical studies have assessed benzonatate for the treatment of cough in more than 2,100 patients.[4]

A systematic review of the literature of benzonatate for cough was published in 2023.[8] The review identified 37 relevant articles including 21 cohort studies, 5 experimental studies, and 11 case studies and series.[8] The data were of very low quality.[8] Most of the studies on benzonatate are decades old and were conducted shortly after its introduction.[12] The systematic review concluded that there is inadequate evidence to support the effectiveness and safety of benzonatate and emphasized rising safety concerns surrounding the drug.[8] It further concluded that there is a need for large observational studies or randomized trials to assess the place of benzonatate in modern medicine.[8]

Hiccups

Benzonatate has been reported to have use in the suppression of hiccups.[7]

Intubation

Benzonatate acts as a local anesthetic and the liquid inside the capsule can be applied in the mouth to numb the oropharynx for awake intubation.[6] However, there can be life-threatening adverse effects when the medication is absorbed by the oral mucosa, including choking, hypersensitivity reactions, and circulatory collapse.[6]

Available forms

Benzonatate is available in the form of 100 mg oral capsules.[4][19]

Contraindications

Hypersensitivity to benzonatate or any related compounds is a contraindication to its administration.[3]

Side effects

Benzonatate is generally well-tolerated if the liquid-capsule is swallowed intact.[6] Potential adverse effects of benzonatate include:

- Constipation, dizziness, fatigue, stuffy nose, nausea, headache are frequently reported.[20]

- Sedation, a feeling of numbness in the chest, sensation of burning in the eyes, a vague "chilly" sensation, itchiness, and rashes are also possible.[6][3]

- Ingestion of a small handful of capsules has caused seizures, cardiac arrhythmia, and death in adults.[21]

Hypersensitivity reactions

Benzonatate is structurally related to anesthetic medications of the para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) class which includes procaine and tetracaine.[3][21][12] Procaine and tetracaine, previously used heavily in the fields of dentistry and anesthesiology, have fallen out of favor due to allergies associated with their metabolites.[21] Similarly, severe hypersensitivity reactions to benzonatate have been reported and include symptoms of laryngospasm, bronchospasm, and cardiovascular collapse.[3][22] These reactions are possibly associated with chewing, sucking, or crushing the capsule in the mouth.[3][21]

Improper use

Benzonatate should be swallowed whole.[3] Crushing or sucking on the liquid-filled capsule, or "softgel," will cause release of benzonatate from the capsule and can produce a temporary local anesthesia of the oral mucosa.[3] Rapid development of numbness of the tongue and choking can occur.[3][21] In severe cases, excessive absorption can lead to laryngospasm, bronchospasm, seizures, and circulatory collapse.[3][21] This may be due to a hypersensitivity reaction to benzonatate or a systemic local anesthetic toxicity, both of which have similar symptoms.[21] There is a potential for these adverse effects to occur at a therapeutic dose, that is, a single capsule, if chewed or sucked on in the mouth.[21]

Psychiatric effects

Isolated cases of bizarre behavior, mental confusion, and visual hallucinations have been reported during concurrent use with other prescribed medications.[3] Central nervous system effects associated with other para-aminobenozic acid (PABA) derivative local anesthetics, for example procaine or tetracaine, could occur with benzonatate and should be considered.[6]

Children

Safety and efficacy in children below the age of ten have not been established.[3] Accidental ingestion resulting in death has been reported in children below the age of ten.[3] Benzonatate may be attractive to children due to its appearance, a round-shaped liquid-filled gelatin capsule, which looks like candy.[22][23] Chewing or sucking of a single capsule can cause death of a small child.[3][23] Signs and symptoms can occur rapidly after ingestion (within 15–20 minutes) and include restlessness, tremors, convulsions, coma, and cardiac arrest.[23] Death has been reported within one hour of ingestion.[20][23]

Pregnancy and breast feeding

It is not known if benzonatate can cause fetal harm to a pregnant woman or if it can affect reproduction capacity.[3][11] Animal reproductive studies have not been conducted with benzonatate to evaluate its teratogenicity.[3]

It is not known whether benzonatate is excreted in human milk.[3][11]

Overdose

Benzonatate is chemically similar to other local anesthetics such as tetracaine and procaine, and shares their pharmacology and toxicology.[21]

Benzonatate overdose is characterized by symptoms of restlessness, tremors, seizures, abnormal heart rhythms (cardiac arrhythmia), cerebral edema, absent breathing (apnea), fast heart beat (tachycardia), and in severe cases, coma and death.[6][3][24][18] Symptoms develop rapidly, typically within 5 minutes to 1 hour of ingestion.[3][18][10][5] Treatment focuses on removal of gastric contents and on managing symptoms of sedation, convulsions, apnea, and cardiac arrhythmia.[3]

Despite a long history of safe and appropriate usage, the safety margin of benzonatate is reportedly narrow.[21] Toxicity above the therapeutic dose is relatively low and ingestion of a small handful of pills can cause symptoms of overdose.[21][18] Children are at an increased risk for toxicity, which have occurred with administration of only one or two capsules.[23][24][18] Following cardiopulmonary collapse with benzonatate overdose, most people have significant neurological deficits or other end-organ damage.[10]

Due to increasing usage of benzonatate and rapid onset of symptoms, there are accumulating cases of benzonatate overdose deaths, especially in children.[18][10]

Pharmacology

Benzonatate is chemically similar to other local anesthetics such as tetracaine and procaine, and shares their pharmacology.[21]

Pharmacodynamics

Similar to other local anesthetics, benzonatate is a potent voltage-gated sodium channel blocker.[21] After absorption and circulation to the respiratory tract, benzonatate acts as a local anesthetic, decreasing the sensitivity of vagal afferent fibers and stretch receptors in the bronchi, alveoli, and pleura in the lower airway and lung.[6][7] This dampens their activity and reduces the cough reflex.[6][3] Benzonatate also has central antitussive activity on the cough center in central nervous system at the level of the medulla.[6][4] However, there is minimal inhibition of the respiratory center at a therapeutic dosage.[3]

Pharmacokinetics

The antitussive effect of benzonatate begins within 15 to 20 minutes after oral administration and typically lasts between 3 and 8 hours.[3][4] THe elimination half-life of benzonatate has been reported to be 1 hour.[5]

Benzonatate is hydrolyzed by plasma butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) to the metabolite 4-(butylamino)benzoic acid (BABA) as well as polyethylene glycol monomethyl ethers.[21] Like many other local anesthetic esters, the hydrolysis of the parent compound is rapid.[21] There are concerns that those with pseudocholinesterase deficiencies may have an increased sensitivity to benzonatate as this hydrolysis is impaired, leading to increased levels of circulating medication.[21]

Aside from oral administration, benzonatate has also been used by a variety of other routes, including rectal administration, subcutaneous injection, intramuscular injection, and intravenous infusion.[4]

Chemistry

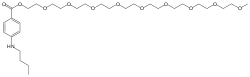

Benzonatate is a butylamine, para-amino-benzoic acid, or long-chain polyglycol, structurally related to other ester local anesthetics such as procaine and tetracaine.[21][5][12] The molecular weight of benzonatate is 603.7 g/mol.[3] However, the reference standard for benzonatate is a mixture of n-ethoxy compounds, differing in the abundance of 7 to 9 repeating units, with an average molecular weight of 612.23 g/mol.[21] There is also evidence that the compound is not uniform between manufacturers.[21]

History

Benzonatate was first synthesized in 1956 and was introduced as an antitussive in the United States in 1958.[4]

Society and culture

Benzonatate was first made available in the United States in 1958 as a prescription medication for the treatment of cough in individuals over the age of 10.[23][24] There are a variety of prescription opioid-based cough relievers, such as hydrocodone and codeine, but have unwanted side effects and potential of abuse and diversion.[21] However, benzonatate is currently the only prescription non-opioid antitussive and its usage has been rapidly increasing.[21][18] The exact reasons of this increase are unclear.[18]

Economics

In the United States between 2004 and 2009, prescriptions increased 50% from 3.1 million to 4.7 million, the market share of benzonatate among antitussives increased from 6.3% to 13%, and the estimated number of children under the age of 10 years receiving benzonatate increased from 10,000 to 19,000.[21][18] Throughout this same period, greater than 90% of prescriptions were given to those 18 or older.[18] The majority of prescriptions were given by general, family, internal, and physicians with pediatricians account for about 3% of prescribed benzonatate.[18]

In 2020, it was the 157th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 3 million prescriptions.[15][16]

Brand names

Tessalon is a brand name version of benzonatate manufactured by Pfizer.[21][18] It is available as perles or capsules.[19] Zonatuss was a brand name manufactured by Atley Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Vertical Pharmaceuticals, Inc.[25][26] Other brand names of benzonatate include Exangit, Tessalin, Tesalon, Tusical, Tusitato, and Ventussin.[1]

Availability

Benzonatate is available in the United States and Mexico.[12][14]

References

- 1 2 Elks J (2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer US. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ↑ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 "Tessalon - benzonatate capsule". DailyMed. 20 November 2019. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Homsi J, Walsh D, Nelson KA (November 2001). "Important drugs for cough in advanced cancer". Supportive Care in Cancer. 9 (8): 565–574. doi:10.1007/s005200100252. PMID 11762966. S2CID 25881426.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00868

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 "Benzonatate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- 1 2 3 Becker DE (2010). "Nausea, vomiting, and hiccups: a review of mechanisms and treatment". Anesthesia Progress. 57 (4): 150–6, quiz 157. doi:10.2344/0003-3006-57.4.150. PMC 3006663. PMID 21174569.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Costantino RC, Leonard J, Gorman EF, Ventura D, Baltz A, Gressler LE (October 2023). "Benzonatate Safety and Effectiveness: A Systematic Review of the Literature". Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 57 (10): 1221–1236. doi:10.1177/10600280221135750. PMID 36688284.

- 1 2 3 "Drugs for cough". The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics. 60 (1562): 206–208. December 2018. PMID 30625123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Minhaj FS, Leonard JB (December 2021). "A description of the clinical course of severe benzonatate poisonings reported in the literature and to NPDS: A systematic review supplemented with NPDS cases". Hum Exp Toxicol. 40 (12_suppl): S39–S48. doi:10.1177/09603271211030560. PMID 34219543.

- 1 2 3 "Benzonatate Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 10 October 2019. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dicpinigaitis PV (April 2009). "Currently available antitussives". Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 22 (2): 148–51. doi:10.1016/j.pupt.2008.08.002. PMID 18771744.

- ↑ Walsh TD, Caraceni AT, Fainsinger R, Foley KM, Glare P, Goh C, et al. (2008). Palliative Medicine E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 751. ISBN 9781437721942.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - 1 2 Schweizerischer Apotheker-Verein (2000). Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Index nominum. Medpharm Scientific Publishers. p. 109. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- 1 2 "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- 1 2 "Benzonatate - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ Estfan B, LeGrand S (November 2004). "Management of cough in advanced cancer". The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2 (6): 523–527. PMID 16302303.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 McLawhorn MW, Goulding MR, Gill RK, Michele TM (January 2013). "Analysis of benzonatate overdoses among adults and children from 1969-2010 by the United States Food and Drug Administration". Pharmacotherapy. 33 (1): 38–43. doi:10.1002/phar.1153. PMID 23307543. S2CID 35165660.

- 1 2 "Tessalon- benzonatate capsule". DailyMed. 20 November 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- 1 2 "Benzonatate (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. 4 March 2020. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bishop-Freeman SC, Shonsey EM, Friederich LW, Beuhler MC, Winecker RE (June 2017). "Benzonatate Toxicity: Nothing to Cough At". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 41 (5): 461–463. doi:10.1093/jat/bkx021. PMID 28334901.

- 1 2 "Drugs for cough". The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics. 60 (1562): 206–208. December 2018. PMID 30625123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Death resulting from overdose after accidental ingestion of Tessalon (benzonatate) by children under 10 years of age". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 June 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- 1 2 3 "In brief: benzonatate warning". The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics. 53 (1357): 9. February 2011. PMID 21304443.

- ↑ "Zonatuss (Benzonatate Capsules USP, 150 mg)". DailyMed. 2 June 2010. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ↑ "Zonatuss (Benzonatate Capsules USP, 150 mg)". DailyMed. 31 October 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2020.