| Tongue River | |

|---|---|

| |

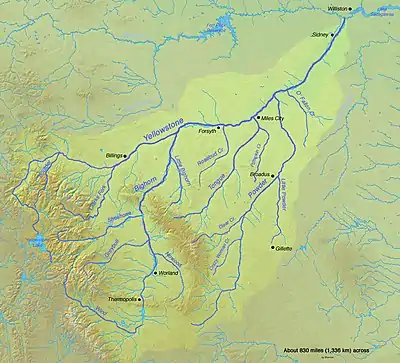

Map of the Yellowstone River watershed with the Tongue River approximately in the center | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Wyoming, Montana |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | |

| • location | Big Horn Mountains, Wyoming |

| • coordinates | 44°49′06″N 107°27′20″W / 44.81833°N 107.45556°W[1] |

| Mouth | Yellowstone River |

• location | Miles City, Montana |

• coordinates | 46°24′33″N 105°52′00″W / 46.40917°N 105.86667°W[1] |

| Length | 265 mi (426 km) |

| Basin size | 5,397 sq mi (13,980 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Miles City, Montana |

| • average | 400 cu ft/s (11 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 13,300 cu ft/s (380 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • right | Pumpkin Creek, Otter Creek, Hanging Woman Creek, Prairie Dog Creek, Goose Creek, Wolf Creek |

The Tongue River is a tributary of the Yellowstone River, approximately 265 mi (426 km) long, in the U.S. states of Wyoming and Montana. The Tongue rises in Wyoming in the Big Horn Mountains, flows generally northeast through northern Wyoming and southeastern Montana, and empties into the Yellowstone River at Miles City, Montana. Most of the course of the river is through the beautiful and varied landscapes of eastern Montana, including the Tongue River Canyon, the Tongue River breaks, the pine hills of southern Montana, and the buttes and grasslands that were formerly the home of vast migratory herds of American bison.

The Tongue River watershed encompasses parts of the Cheyenne and Crow Reservations in Montana. The headwaters lie on the Bighorn National Forest in Wyoming, and the watershed encompasses the Ashland Ranger District of the Custer National Forest. The river's name corresponds to Cheyenne /vetanoveo'he/, where /vetanove/ means "tongue" and /o'he'e/ means "river".[2]

Geography

The Tongue River is fed by winter snowpack from the higher elevations of the Big Horn Mountains, early snow runoff of the lower elevations in the drainage basin, and ground water from springs in the drainage basin. The river level rises in March and April due to snowmelt in the lower elevations, and again in June as summer weather melts the higher-elevation snowpack. The flow of water in the upper river during the summer is generally steady, but in the later months of a dry summer, irrigation can reduce the lower river to a few pools of water connected by a small trickle. The river is generally frozen during the winter months.

The source of the Tongue River is in the highlands of the Big Horn Mountains in north-central Wyoming. The river descends the eastern side of the mountains and emerges from a canyon near Dayton, Wyoming. The river then flows eastward, past Ranchester, Wyoming, and merges with Goose Creek, after which the Tongue turns to flow northeast into Montana, where it is dammed, forming the Tongue River Reservoir. Continuing northeast from the reservoir, the river flows through a prairie canyon and the Tongue River breaks, passing Birney, Montana.

The river forms the eastern boundary of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation from about 25 miles (40 km) north of the reservoir to a point 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Ashland, Montana, after which the river continues to flow in a broad valley to its mouth on the Yellowstone River near Miles City, Montana. The Tongue River Valley near Decker, Montana also contains the southeast corner of the large Crow Indian Reservation.

The Tongue River headwaters are on the Bighorn National Forest. On forested buttes lying between the Tongue River and Pumpkin Creek is the Ashland Ranger District of the Custer National Forest, which has three separate ranger districts, the other two being the Beartooth Ranger District located in the area of the Beartooth uplift, and the Sioux Ranger District located in the southeast corner of Montana and the northwest corner of South Dakota.

The term "Tongue River Canyon" can refer to either the river's mountain canyon in the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming, or the river's prairie canyon in Montana, located downstream from the Tongue River Dam and Reservoir.

The major tributaries of the Tongue are Pumpkin Creek, Otter Creek, Hanging Woman Creek, Prairie Dog Creek and Goose Creek. All of these tributaries enter on the eastern side of the river, and all flow in a northerly direction.

Pumpkin Creek meets the Tongue about 13 miles (21 km) above the mouth of the river, and extends for 71 miles (114 km) into the Custer National Forest; the small community of Sonnette, Montana is at the headwaters. Otter Creek enters the Tongue River near Ashland, Montana, about 68 miles (109 km) upstream of the mouth of the river, and its headwaters are near the Wyoming–Montana state line about 40 miles (64 km) to the south. Hanging Woman Creek empties into the Tongue at Birney, Montana, about 91 miles (146 km) above the mouth of the Tongue, and its headwaters are 35 miles (56 km) away in northern Wyoming. Prairie Dog Creek and Goose Creek flow into the Tongue at the point where the Tongue turns from an eastward direction to flow toward the northeast. Goose Creek drains a scenic, well-watered basin in Wyoming, on the eastern edge of the Big Horn Mountains, where Sheridan and Big Horn, Wyoming are located.

The drainage basin to the west is the Rosebud Creek basin. The drainage basin to the east is the Powder River basin. Both rivers, like the Tongue, flow in a northerly direction into the Yellowstone River.

The Tongue and its tributaries flow through parts of Custer, Powder River, Rosebud and Big Horn counties in Montana, and Sheridan County in Wyoming.

Climate

According to the Köppen climate classification system, the Tongue River has a semi-arid climate, abbreviated "BSk" on climate maps.[3]

Geology

The Tongue River basin is part of the larger geologic structure known as the Powder River basin. The term Powder River basin can refer to the topographic drainage basin lying to the east of the Tongue River drainage basin, but the term is used in this part to denote the larger geological structure which stretches from the Black Hills to the Big Horn Mountains and which includes the Tongue River drainage area.

The Powder River basin is shaped like a large shallow bowl, with its westernmost rock formations lying against the Big Horn Mountains. As these mountains uplifted over eons of geologic time they lifted and tilted the sedimentary rocks from the Powder River basin, which were then eroded away, creating the plains that stretch eastward from the mountains into the basin. Generally there are older sedimentary layers closer to the mountains and younger layers farther away.

As the Tongue flows out from the Big Horn Mountains it passes over the uplifted layers of increasingly younger sedimentary rocks. In the Big Horn Mountains the Tongue flows in its mountain canyon of Madison Limestone, which was deposited during Early to Middle Mississippian time, about 359 to 326 million years ago. As the Tongue leaves the mountains it flows through younger formations, including the distinctive thick red Chugwater Formation, deposited during the Triassic time, 250 to 199 million years ago. Shortly after leaving the mountains, the Tongue River enters an area dominated by a thick layer of buff-colored sandstones and silty clay. This sedmintary layer is named the Tongue River Sandstone, because its outcrops are so predominant in the Tongue River basin.[4] The Tongue River Sandstone is the youngest of three "members" which form the Fort Union Formation, the other two members being the Lebo Shale Member and the Tullock Member.[5]

The buff-colored sandstones and shales of the Tongue River sandstone are visible all along the greater part of the Tongue River from Dayton, Wyoming to a point north of Ashland, Montana. In this stretch, the sandstone layers of the Tongue River member hold ground water so that the highlands on each side of the Tongue River valley are often covered with pines. As the river approaches Miles City the valley changes appearance to grassy rolling hills, as the river leaves the Tongue River formation and flows through the Lebo shale and the Tullock sedimentary formations.

The Tongue River sandstone member outcrops widely over portions of southeast Montana and northeast Wyoming and it is best known for its coal. The Tongue River member has approximately 32 coal seams with a combined thickness in excess of 300 ft.[5] The thickness of the separate coal seams varies radically from place to place—in some places the beds are thick but over a relatively short distance the seam can pinch out to nothing. Where these coal beds are thick and also close to the surface in the Powder River Basin in northern Wyoming and southern Montana they are mined in large open pit mines, like the mines along the Tongue in the vicinity of Decker, Montana. Tongue River coal is low in sulfur content and coal-fired electric generating places throughout the United States demand Tongue River coal so they can meet federal emission standards. Because of this demand, about 40% of the coal now used to generate electricity in the United States is mined from the Tongue River sandstone coal seams in the Powder River Basin, producing 14% of carbon dioxide emissions in the United States.[6]

Where the Tongue River now flows in Montana and Wyoming, the sedimentary rock formation that is today known as the Tongue River sandstone began to form about 60 million years ago, when mountain uplifts began rising from a shallow sea. The Black Hills uplift on the east, the Hartville uplift on the southeast, and the Big Horn Block on the west created a flat, swampy low-lying plain, with slow moving rivers flowing northwest to deltas along a shallow sea.[7][8] At this time the climate in the area was subtropical, averaging approximately 120 inches (3,000 mm) of rainfall a year. For some 25 million years, the floor of this plain was made up of thick deposits of sandy silt from the surrounding mountains, with many rivers, deltas, backwaters and swamps, all covered by forests and vegetation. At that time, from 35 to 60 million years ago, the area where the Tongue River now flows would have appeared as a dense swampy jungle. Over long periods of time, the heavy plant growth died and accumulated as peaty layers in the large backwaters and swamps all across the basin.[9] Periodically more sandy silt deposits would wash in from the mountains, completely burying the layers of organic peaty materials. Eventually the climate became drier and cooler. The area passed through more long periods of geologic time, during which new sedimentary layers buried this entire sandy silty layer along with its deposits of peat, under thousands of feet of newer sediments, compressing the sandy silty deposits into the Tongue River sandstone of today, and also compressing and changing the layers of peaty organic material into thinner layers of lignite coal. Over the last several million years, much of the overlying sediment has eroded away, bringing the sandstone layer with its seams of coal to the surface again in the Tongue River area.

The Tongue River sandstone forms cliffs, hills, buttes and bluffs along the river and throughout the basin.[10] From the Decker area downstream to about Birney the river flows through the prairie in a canyon carved from the Tongue River sandstone. The upper part of this canyon is dammed to form the Tongue River Reservoir.

The sandstone hillsides and bluffs along the Tongue and its tributaries often have reddish bands running through them or they are capped with resistant reddish layer. These red layers were formed millions of years ago. Coal seams outcropping in the Tongue River sandstone caught fire, probably from prairie fires that started by lightning. The fires burned from the outcropo back into the coal seams, and the fire finally went out when they burned so deeply into the coal seam that the fire was smothered. These fires burned for a long time and they were extremely hot, and they baked and changed the structure of the sedimentary rocks that lay just over the coal seam until it became a hard "clinker" substance and turned a reddish brick color. These red "clinker" beds are often more resistant to erosion than the silty sandstone, so they appear on the higher parts of bluffs, and buttes on either side of the valleys of the Tongue River basin are often capped by beds of this baked and fused rock that are five to twenty feet thick.[11] Besides the beds of reddish "clinker" larger concretions can be found that appear at first glance to be similar to melted glass or even pieces of volcanic rock. Although of a different appearance than the clinker these odd-looking concretions are also formed by the burning coal beds, with the difference in appearance being due to the difference in content of the material in the overlying bed that was heated to very high temperatures. The reddish "clinker" is crushed and used to surface roads throughout the Tongue River basin.

North of the Yellowstone, dinosaur fossils have been found in Cretaceous era rock formations, but dinosaur fossils have not been found in any members of the Paleozoic Fort Union Formation, including the Tongue River sandstone. However plant fossils are common in the Tongue River sandstone, and many imprints of leaves and fronds have been found and collected by scientists and fossil hunters.[12][13]

History

Early history

In about 1450, Crow leader No Intestines received a vision and separated from the ancestral tribe, which remained along the Missouri River as sedentary farmers known as Hidatsa. No Intestines led his band on a long migratory search for sacred tobacco, finally settling in southeastern Montana, where they became known as the Many Lodges or Mountain Crow. By 1490, the Crow were firmly established in a homeland that included the Tongue River valley–in south central/southeastern Montana, and northern Wyoming. To acquire control of this area, the Crow warred against Shoshone bands, and drove them westward, but allied themselves with local Kiowa and Kiowa Apache bands.[14][15][16]

The Crow were a Northern high plains, nomadic, bison hunting culture based on the dog travois[17][18] but in about 1700 they acquired horses and swiftly evolved a horse based nomadic hunting culture.[15][16] The Kiowa bands migrated southward, and the Crow remained dominant in an extensive area, including the Tongue River, in south central Montana through the 18th century, 19th century and the era of the fur trade.

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 confirmed a large area centered on the Big Horn Mountains as Crow lands—the area ran from the Big Horn Basin on the west, to the Musselshell River on the north, and east to the Powder River, and included the Tongue River basin.[19] However, for two centuries, the Cheyenne and the many bands of Lakota people had been steadily migrating westward into the plains, and by 1851 they were established just to the south and east of Crow territory in Montana.[20] The Lakota along with their Cheyenne allies coveted the fine hunting lands where the Crow lived and after 1851 the Lakota and Cheyenne fought the Crow and took control of their eastern hunting lands, including the Powder and Tongue River valleys, pushing the less numerous Crow to the west and northwest along the Yellowstone River.[20]

After about 1860 the Lakota claimed all the lands lying east of the Big Horn Mountains and required the whites to deal with them regarding any intrusion into these areas.[20] Red Cloud's War (1866 to 1868) was a challenge by the Lakota to the military presence on the Bozeman Trail, which went to the Montana gold fields along the eastern edge of the Big Horn Mountains. Red Cloud's War ended in a complete victory for the Lakota, and the 1868 Treaty of Ft. Laramie confirmed their control over all the high plains from the crest of the Big Horn Mountains eastward across the Powder River Basin to the Black Hills.[21] Thereafter bands of Lakota led by Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and others, along with their Northern Cheyenne allies, hunted and raided throughout the length and breadth of eastern Montana and northeastern Wyoming, including the area of the Tongue River Valley, until the Great Sioux War of 1876–1877. Although early in the war on June 25, 1876 the Lakota and Cheyenne enjoyed a major victory over army forces under General George A. Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, the Great Sioux War ended in the defeat of the Sioux and their Cheyenne allies, and their exodus from eastern Montana and Wyoming, either in flight to Canada or by forced removal to distant reservations.

In 1877, the Northern Cheyenne, allied with the Lakota, were ordered south to a reservation in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) with the related but separate Southern Cheyenne tribes. Plagued with disease and malnutrition, in 1878 a group of 279 Northern Cheyenne made a desperate attempt to return to the northern plains. After a running battle from Indian Territory to Montana, the battered remnants of this group arrived at Ft. Keogh, at the mouth of the Tongue, where a Northern Cheyenne band under Two Moons remained which had yet not been sent south. General Miles allowed Ft. Keogh to become a gathering point for the scattered Northern Cheyenne people. Over time Cheyenne families began to migrate south from the fort and establish homesteads up the Tongue River and on the Rosebud. By executive orders in 1884 and 1900, the federal government carved out a reservation for the Northern Cheyenne on Rosebud Creek, with the Tongue River as its eastern boundary.[22]

Fur trading era

In September 1833 on the Tongue River, a chapter was written in the rivalry between the Rocky Mountain Fur Company (RMF) and the American Fur Company (AFC). Tom Fitzpatrick, a mountain man and fur trader with the RMF, rode to Crow camps on Tongue River with a band of about 30 other trappers to trade for furs and to ask permission of the chiefs to make his fall hunt in their country. The Crows invited Tom to camp with them. He cautiously declined and pitched his camp three miles off. Then he rode over with a few men to visit the chief, who received and entertained him cordially. The AFC was a rival of Tom Fitzpatrick's RMF Company and they had agents in the Crow villages including the notorious James Beckwourth, who was an adopted member of the tribe. While Fitzpatrick was visiting the Crow camp, young Crow warriors, probably instigated by AFC agents, rode to Fitzpatrick's camp and proceeded to steal all of his horses, rifles, traps, and equipment, as well as his beaver pelts and trade goods. Fitzpatrick's camp was being guarded by 25 of his men under Captain William Drummond Stewart, a former British officer (and veteran of Waterloo) and no pushover. Upon entering the trappers camp, the collection of Crow warriors probably first affected an excessive cordiality and when their demonstrations of friendship and claims of affection had literally and figuratively disarmed the trappers, "then the knives, clubs, bows and guns were out, and a Crow was attached to everything of value."[23] The warriors even took Capt. Stewart's watch.[23] Upon meeting Tom Fitzpatrick as he returned from the village, the young warriors completed their work by robbing him of his capote coat.[24] The next day, Fitzpatrick, always a realist, returned to the Crow camp and begged his former friend, the Crow Chief for help and received back some of his horses, rifles, traps and other equipment, and a small amount of ammunition per man, but no furs or trade goods.[25]

In 1835 Samuel Tullock of the American Fur Company (AFC) built Fort Van Buren on the right bank of the Yellowstone. Although the precise location of this fort is in dispute, it was located along the Yellowstone River, in an area near the mouth of the Tongue River. At the fort, AFC agents traded for furs with Indians from the surrounding area. The fort was abandoned in 1842, and later burned.[26]

Indian wars

Bozeman Trail and Red Cloud's War

In 1864, the Bozeman Trail was opened to the Montana gold fields. A portion of the trail entered the Tongue River Basin at Prairie Dog Creek[27] and crossed over to Goose Creek and went on to the Tongue River beyond present day Ranchester, Wyoming then up the Tongue River to the Pass Creek divide. After the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado in November 1864, depredations by Cheyenne, Arapahoe and Sioux increased along the Oregon Trail and the Bozeman Trail, which was then closed to civilian traffic. The army launched a punitive campaign, and Brigadier General Patrick Edward Connor led a column up the Bozeman Trail. On August 29, 1865, General Conner, with a force variously estimated at about 300 soldiers, surprised an Arapahoe village of about 500 to 700 under Chiefs Old David and Black Bear camped on the Bozeman Trail, on the south side of the Tongue near present-day Ranchester, Wyoming. In what is now known as the Battle of the Tongue River the soldiers charged into the Indian camp firing indiscriminately, surprising the Indians who were breaking camp. The Indians first fled up Wolf Creek, but then regrouped and counter-attacked. The soldiers destroyed about 250 lodges, then retreated down the Tongue River Valley driving from 700 to 1000 captured horses, repulsing attacks of Arapahoe warriors seeking to get back some of their horses.[28][29]

Two days after the battle with Conner, on August 31, 1865, warriors from the same Arapahoe village attacked a large wagon train of road-builders led by "Colonel" James A. Sawyers,[30] who were traveling on the Bozeman Trail, improving it as they went. The wagon train was besieged for 13 days at the Bozeman Trail ford on the Tongue River about halfway between Ranchester, Wyoming and Dayton, Wyoming.[31] As the siege dragged on and a number of men were killed, Sawyers faced mutiny from his employees.[32] Sawyers had started to retreat down the trail, when he met a contingent of army cavalry moving up the trail, who agreed to escort them to the Big Horn River, after which the wagon train proceeded on to the Montana gold fields.[33]

In 1866, the army determined to erect a series of forts along the Bozeman Trail. The scout Jim Bridger recommended a fort site in the Tongue River Valley, near Ranchester, Wyoming. Col. Henry B. Carrington rejected the Tongue River site for a site to the south on Little Piney Creek, in the Powder River drainage, where Fort Phil Kearny was erected.[34]

From 1865 through 1868 during Red Cloud's War, Cheyenne and Lakota Sioux bands harassed, attacked and killed travelers on the Bozeman Trail and soldiers at Fort Phil Kearny and Fort C. F. Smith. These bands often located their base camps on the Tongue River because they could camp far enough down the river from the forts to be secure from counterattack, and the lower Tongue River Valley afforded a wide variety of camp sites with the three necessities of the nomadic Indians – wood for fires, abundant water, and adequate grass for grazing their large horse herds.

1873 Yellowstone Expedition (1873 Northern Pacific railroad survey)

Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, with Companies A and B of the Seventh Cavalry, engaged and held off a larger Sioux force, including Hunkpapas, Oglalas, Miniconjous and Cheyennes at the Battle of Honsinger Bluff on August 4, 1873 about 7 miles (11 km) above the mouth of the Tongue on the Yellowstone River.[35] Custer's command was part of the Stanley military column which was accompanying and protecting Northern Pacific Railroad survey parties in the summer months of 1873. Many of the Indian leaders and army officers who participated in the Battle of Honsinger Bluff were present at the more famous Battle of the Little Big Horn on June 25, 1876, three years later.

Great Sioux War of 1876–77

In a June 9, 1876 engagement called the Skirmish at Tongue River Heights, during the Great Sioux War of 1876-77 General George Crook was camped on the Tongue near the mouth of Prairie Dog Creek with about 950 soldiers, when Sioux fired into his camp from a bluff across the Tongue. A battalion under Captain Anson Mills responded, crossing the river and driving the Sioux force from the bluffs.[36] As a consequence of this engagement, on June 11, General Crook moved his base camp to the junction of Big and Little Goose Creeks, some 7 miles south of the junction of Goose Creek and the Tongue River, where Sheridan, Wyoming is now located.[37] On June 16, after being joined on the Tongue by some 260 Crow and Shoshone scouts, Crook moved his forces north, across the Tongue, and on June 17, 1876 engaged a large Sioux and Cheyenne force at the Battle of the Rosebud. After the battle Crook returned south of the Tongue River to the base camp on Goose Creek, and he was still there on June 25, 1876 when General George A. Custer was defeated at the Battle of the Little Big Horn, some 65 miles to the north.

After remaining idle for more than two weeks on Goose Creek, on July 6, 1876 General George Crook ordered Second Lieutenant Frederick W. Sibley to take 25 men and two scouts, Big Bat Pourier and Frank Grouard, and make a reconnaissance to the north to locate the hostile Indian forces. While traveling up the Tongue River in the vicinity of (present day) Dayton, Wyoming, the patrol discovered a large party of Sioux and Cheyenne warriors moving south and very close to them. The only chance was to turn aside and take a trail near Dayton that led up into the adjacent Big Horn Mountains. The war party followed closely, and after surviving attacks by pursuing Indians, the patrol abandoned their horses and traveled deep into the rough steep terraine of the Tongue River Canyon system on foot. Over several days the group was able to evade the Indian force, after which they walked over thirty miles out of the mountains and back to the Goose Creek camp, arriving worn out and fatigued but with no casualties. The "Sibley Scout" became another incident of the Great Sioux War of 1876 that took place along the Tongue River.[38][39]

In the fall of 1876 following the defeat of Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the army determined to garrison the area, and Colonel Nelson A. Miles and elements of infantry units constructed the Tongue River Cantonment at the mouth of the Tongue River.[40] A community formed nearby named "Milestown" after Col. Miles who banished the settlement to a point three miles away from the cantonment. In the following year, after a vigorous winter campaign, the army increased the commitment of forces and Col. Miles constructed Fort Keogh about 2 miles (3.2 km) west of the Tongue.[40] After the fort was finished, Miles permitted civilians to settle on the eastern bank of the Tongue. Immediately, Milestown moved 3 miles (4.8 km) west forming Miles City. Today, the Tongue joins with the Yellowstone within the city limits of Miles City.

On December 16, 1876 five Sioux chiefs from Crazy Horse's village approached the Tongue River Cantonment to discuss terms of surrender for their bands. The Sioux were the hereditary enemies of the Crow, and the five Sioux were suddenly attacked and killed by some of the army's Crow scouts. The attack occurred within sight of the Cantonment, but was so swift and unexpected that the army could not intervene to save the chiefs. The Crow scouts involved immediately fled from the area. This episode delayed surrender of Sioux and Cheyenne bands, and extended the Great Sioux War of 1876–1877.[41][42]

On January 8, 1877 Colonel Miles and infantry units engaged in one of the last battles of the Great Sioux War of 1876-77 near Birney, Montana in the Tongue River Valley. Colonel Miles, leading elements of the 5th and 22nd infantry, avoided an ambush by Oglala Sioux under Crazy Horse, and segments of Cheyenne under White Bull and Two Moons, and then engaged the Indian forces driving them back up the Tongue River.[43] The battle is officially referred to as the Battle of the Wolf Mountains, although this is a misnomer. The battle is also referred to by various other names, including the Battle of Pyramid Butte, the Battle of the Butte, and Miles Battle on the Tongue River. The Wolf Mountains are actually several drainages to the west from the battle site, but General Miles' report stated the battle was in the Wolf Mountains, and that name has stuck. The battle site is about 4.5 road miles west of the town of Birney, on the Tongue River road.

Lumber

A sawmill operates at Ashland, cutting timber which is harvested from the broken highlands, between the stream valleys in the surrounding area.

Agriculture and irrigation

The Tongue River basin is prime livestock country. Limited farm lands that exist along flowing streams in the basin are usually irrigated from diversion dams, and produce crops which support the livestock industry—hay and feed stocks (corn, barley, alfalfa). Dry land wheat farming, which is prevalent elsewhere in eastern Montana, occurs only in limited and scattered acreages in the Tongue River basin. Cattle represent the great bulk of the total livestock production from the Tongue River basin with sheep a distant second.

Cattle ranches in the Tongue River Basin are predominantly "cow calf" instead of "yearling" operations. The yearly cycle of a "cow calf" operation begins with the birth of calves from February to May. At spring roundup the calves are branded. Bulls are put with the cows to start the nine-month gestation cycle to produce next year's calf crop on the month chosen by the rancher, after which the bulls are again separated from the herds. The herds are moved to summer pasture, and in June and July attention focuses on cutting and storing hay for the next winter. Feed crops are harvested in late summer or fall. The late fall roundup separates the calves which are sold to cattle buyers and shipped by truck. The herd is moved to the pasture where they will be fed for the winter, and in about the first week of December enough snow accumulates to start the process of feeding hay to carry the herd through the winter. Ranch chores, repairs and maintenance, work on building projects, doctoring cattle and the like go on all year round.

One of the oldest irrigation projects on the Tongue River is the T&Y Ditch, which dates from 1886. The diversion dam from the T&Y ditch was recently altered to include a fish ladder, which now allows fish from the Tongue and Yellowstone Rivers below the dam to migrate upriver, for the first time in 125 years.

Coal deposits and coal mines

Historically, underground coal mines existed along the Tongue River at the communities of Monarch, Kleenburn and Acme, about 7 to 10 miles north of Sheridan, Wyoming. These mines were based on seams of coal that outcropped in this area, in the Tongue River valley or on small tributaries off the valley. The CB&Q railroad ran from Sheridan, Wyoming past these mines and on to Billings, Montana, allowing for easy shipment of coal. These underground mines were economically operated from about 1900 to the late 1940s.[44] Miners lived in these communities or in Sheridan, Wyoming. Miners in Sheridan commuted the 7 to 10 miles to reach the mines by trolly.[45]

The same coal seams that used to be mined by tunnels are now accessed for mining by large open surface excavations. Several large coal strip mines are presently operating in the area around the Tongue River Reservoir, near the small town of Decker, Montana about 20 to 23 miles northeast from Sheridan, Wyoming. These mines are operated by the Kiewit Corporation and produce subbituminous low sulfur Powder River basin coal.[46] There are no electrical generating facilities at this site. A rail spur line extends to the mine sites from the BNSF main line near Sheridan, Wyoming allows this coal to be shipped by rail to coal-fired electric generating plants all over the United States.

Large undeveloped private and federally owned coal deposits are located along Otter Creek, a tributary of the Tongue River. These coal deposits are located south of Ashland, which is at the junction of the Tongue River and Otter Creek. These coal deposits are sufficiently thick, and are located under sufficiently thin overburden, as to be economically viable. Drawbacks for production are the lack of a rail spur to transport the coal, and the lack of an established community of sufficient size in the area to support the work force needed to develop the coal mines. A railroad spur line, if built, would have to come up the Tongue River from Miles City, a distance of some 65 to 70 miles. Extensive infrastructure improvements would have to be added to the community of Ashland before it could support the number of worker's families that the mine would draw to the area. These deposits on Otter Creek are the source of much debate over the future of energy development in southeastern Montana. Arch Coal has submitted an application to develop a coal mine in the area, but it has not, as of 2015, been approved by state regulators.[47] The Tongue River Railroad project, planned to move coal from the mine to Colstrip, is also in the permitting stage.

Undeveloped but extensive coal deposits exist along Youngs Creek and adjacent creeks, which flow into the Tongue River just upstream from the Tongue River Reservoir. This large and (as yet) untapped deposit of coal is just a few miles south of the large open pit coal mines already being operated by Kiewit. The upper 15 miles of Youngs Creek lies on the Crow Indian Reservation in Montana, and the Crow Tribe owns the coal beds underlying this portion of the creek. The last 3 miles of the creek lie between the reservation boundary and the Tongue River, in Wyoming. As to the coal beds on the Crow reservation, the Secretary of the Interior approved a coal lease negotiated by the Crow Tribe with Shell Oil Company in 1983 to develop this coal resource.[48] The lease had extensive long term benefits for the Crow tribe, and required payments to the tribe to start at a future point of time even in the event the coal was not mined. Shell paid the tribe a bonus to cancel this lease in 1985, because of poor market conditions, and because of Shell's uncertainties on how Montana's severance tax would be applied to coal owned by the Crow Tribe.[49] Compared to Otter Creek these coal resources are easier to develop—the coal resources of Young's creek lies within five to ten miles of the railroad spur line which is used to ship coal from the nearby open pit mines being operated by Kiewit in the Decker, Montana area, and the communities of Sheridan and Ranchester already exist to serve as a base for the work force needed to develop coal mines at Youngs Creek.

Transportation and access

Roads and travel conditions

I-94, an east–west interstate artery carrying U.S. Highway 12, crosses the Tongue at its mouth at Miles City. I-90, also an east–west interstate artery carrying U.S. Highway 87 and U.S. Highway 14, crosses the upper reaches of the Tongue between Ranchester and Dayton, and continues to Sheridan. U.S. Highway 212 extends east and west from Ashland bisecting the middle of the Tongue River basin from side to side.

The Tongue River has a road running along almost all of its length, as do the major tributaries, but the predominance of gravel roads over paved roads is a testament to the remoteness of the region. In the Tongue River valley, starting from Miles City and going up the river there are about 30 miles of pavement to the community of Garland, then 35 miles of gravel, followed by about 7 miles of paved road into Ashland, where U.S. Highway 212 is encountered. South of Ashland, continuing up the valley, there is another 20 miles of paved road, then another 38 miles of gravel roads to the pavement above the Tongue River Reservoir, followed by 10 miles of pavement to the Montana/Wyoming state line. In Wyoming a network of paved roads follow the Tongue river westward to Ranchester and Dayton, where the Tongue comes out of the Big Horn Mountains. A road from Dayton goes up the Tongue for a short distance into the mountains, after which contact with the Tongue River and its mountain branches is by hiking trail.

The lower major tributaries of the Tongue (Pumpkin Creek, Ottor Creek, Hanging Woman Creek, Prairie Dog Creek) all have gravel roads branching off the Tongue River Road and running along their length, providing access to local ranches. In Wyoming, the major tributary is Goose Creek, which flows out of a basin with Sheridan, Wyoming at its center, and so this entire basin area has well-developed paved and gravel roads. In addition to the roads that run along the Tongue and its major tributaries, there is a network of gravel roads that cross the highlands between the stream valleys.

During the winter, travel along the roads in the basin can become difficult to impossible depending on snow accumulation, particularly on the more remote gravel roads that are not regularly plowed. If road conditions or car trouble strand a motorist in the more remote areas of the basin, during the pulses of intense winter cold common to this area, there is a real risk of death or injury by freezing. The Tongue River basin does not have the "gumbo" type mud that affects road travel in wet weather on the north side of the Yellowstone River. Traffic on the gravel and dirt roads of the Tongue River basin is a problem at sharp corners, blind hilltops, concealed entrances to side roads, and when suddenly encountering oversized slow ranch/farm vehicles. In warm weather it is a good idea to keep an eye out ahead for dust clouds indicating approaching vehicles. The motorist traveling in the Tongue River basin should keep a constant look out for livestock on the road, and especially for deer (particularly at dawn, dusk and at night).

There are good roadside services at Miles City, Montana at the mouth of the Tongue River basin, and also in the upper reaches of the basin at Dayton and Ranchester and in the vicinity of Sheridan, Wyoming. There are limited roadside services in Ashland, located about the center of the basin, where U.S. 212 goes east and west. For the rest of the Tongue River basin, the motorist is on his or her own.

Railroads

Since the settlement of Miles City, at the mouth of the Tongue, and the related settlement of Sheridan, Wyoming, located approximately 125 air miles to the south there has been much discussion of a north–south railroad connecting the cities and corridored along the Tongue River valley.[50] This has been the subject of many promotional business ventures over the years.

From 1923 to 1935 the North and South Railway promoted a rail line south from Miles City, Montana through Sheridan to Casper, Wyoming. The northern segment was to run along the Tongue between Miles City, Montana and Sheridan, Wyoming. The southern segment was to run from Casper to Sheridan, Wyoming. Track was only laid on a portion of the southern segment. However, grading was done on the northern segment, and cuts and embankments can still be seen approximately 7 miles south of Miles City on the east side of the Tongue River. Financial problems caused the entire railroad project to be abandoned in 1935.

The current venture is the Tongue River Railroad, in various stages of planning for more than 30 years and intended to move coal from near Ashland to Colstrip.

The BNSF railroad operating between Sheridan, Wyoming and Billings, Montana runs along the Tongue for a distance of about 10 miles, starting from a point about 7 miles north of Sheridan, Wyoming. Though this segment of rail line along the Tongue was limited, from 1900 to 1940 coal was shipped by the railroad from underground coal mines located in the Tongue River valley, along this stretch of track. This railroad was a part of the former Chicago, Burlington & Quincy (CB&Q, or "Burlington") railroad system, which has now been merged in the present Burlington, Northern, Santa Fe (BNSF) railroad system.

The Northern Pacific Railroad built track to Miles City, crossing the Tongue River in 1881,[51] about a mile from the junction of the Tongue and the Yellowstone. This construction was part of the mainline from St. Paul, Minnesota to the Pacific port of Tacoma, Washington completed in 1883,[51] and it is still in operation today as part of the BNSF (Burlington Northern Santa Fe) railroad.

The Milwaukee Road (the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway) completed its mainline from the midwest to Puget Sound in 1909.[52] This line also passed through Miles City and crossed the Tongue River between the existing NP tracks and the Yellowstone River. This line failed in the early 1980s and is no longer in use today.

Wildlife and fisheries

The Tongue River Valley, before it reaches the Big Horn Mountains, is part of an extensive drainage basin which is an environment in which wild game thrives. In this area of rolling prairies, sandstone outcrops and ponderosa pines, there are plentiful numbers of whitetail deer and mule deer, many of trophy quality. Antelope are found throughout this area. On the more southern tributaries, particularly in the Custer National Forest area, there are growing herds of prairie elk, an animal originally native to the plains of eastern Montana. Throughout the area are upland game birds, notably pheasant and grouse, and increasingly abundant flocks of wild turkeys.

The headwaters of the Tongue located in the Big Horn National Forest, in the Big Horn Mountains provide resources for deer, elk, bear and mountain lion hunting.

The grey wolf is an issue if not yet a reality in the Tongue River Basin, and there have been unconfirmed sightings of wolves in the more remote areas of the basin. Livestock, particularly sheep and calves, are vulnerable to wolves and, according to reports, livestock suffered significant depredations by wolves and coyotes in the last part of the 19th and the first part of the 20th century. This led to a war on these predators, with bounties paid by livestock associations and state agencies.[53] By the mid-1930s wolves had been exterminated completely in the Tongue River basin (and indeed throughout the stockgrowing west). Times changed, and sympathy grew for the wolf, as well as his cousin the coyote. Since the release of wolves in Yellowstone Park in 1995, there has been increasing concern by stockgrowers in surrounding areas that wolf packs would migrate out of the park to cattle country and re-establish themselves where the pickings were better. In cattle and sheep country like the Tongue River basin, the debate about wolf reintroduction is ongoing and far from resolved.

The Tongue River Reservoir is popular among fishermen for a variety of fish. Very large catfish have been caught at the reservoir.[54] In its upper reaches above the Tongue River Reservoir, and extending into the Big Horn Mountains, the Tongue River is fished for trout. Follow the footnote for six access points in Wyoming, five of them in the mountain section of the Tongue.[55]

The Tongue is a Class I river from Tongue River Dam to its confluence with the Yellowstone River for public access and for recreational purposes.[56]

Literary references

Otter Creek and Goose Creek, tributaries of the Tongue, are the location of Sam Morton's historical novel, "Where the Rivers Run North".[57]

Ernest Hemingway wrote a short story, "Wine of Wyoming" that references coal miners living at Sheridan, Wyoming during the era of prohibition, who worked at the underground coal mines in the Tongue River valley, a few miles north of Sheridan. The story "Wine of Wyoming" was published in 1933 as part of a collection of Ernest Hemingway's short stories entitled "Winner Take Nothing".

The Tongue River valley and surrounding area is the setting for "A Bride Goes West", an autobiography of Nannie Alderson, which relates her life as a ranch wife in the late 19th century in south central Montana.[58]

Edmund Randolph wrote a book "Hell Among the Yearlings" about his experiences living on a ranch on the Tongue River in the 1920s, and getting into the cattle business.[59]

See also

Notes

There are five "woman" creeks in Wyoming and Montana.

- Hanging Woman Creek is a tributary of the Tongue River, and joins that river at the small community of Birney, Montana.

- Crazy Woman Creek lies to the south of the Tongue River Basin, in Wyoming and is a tributary of the Powder River.

- Swimming Woman Creek flows from the south facing slopes of Montana's Snowy Mountains into Careless Creek and then into the Musselshell River.

- Dirty Woman Creek is a short drainage starting just east of Rock Springs, Montana, and ending just east of Angela, Montana.

- Kill Woman Creek is a short creek flowing into the Ft. Peck Reservoir (Missouri River Drainage) just east of Herman Point, near the UL Bend Wilderness area.

External links

- "Tongue River Reservoir State Park". Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks Department. Archived from the original on 2009-01-07.

- "Tongue River Reservoir State Park". Montana Tourism Site. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28.

- Wyoming Fishing Net; Access Points for fishing the Tongue River in Wyoming

- Fishing information about the upper Tongue river in the Big Horn Mountains

- USGS data for the Tongue River watershed

- Osborne, Thomas J.; Anderson, Stephanie (September 2011), "HydroSolutions, Inc." (PDF), Tongue River Hydrologic Summary Report (PDF) (2011 ed.), Billings, MT: Montana Board of Oil & Gas Conservation, archived from the original on 22 October 2012, retrieved 21 May 2012

- "Decker Coal Company". Kiewit Company. Archived from the original on 2009-05-30.

- Custer National Forest homepage

- Northern Cheyenne Tribe, official website

- Crow Tribe, official website

- Sheridan Wyoming Tourism website

- Website devoted to Miles City, Montana

- Rosebud Battlefield State Park

- Tongue River Winery web site

- Tongue River Stories

References

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Tongue River, USGS GNIS

- ↑ Bright, William (2004). Native American placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 505. ISBN 978-0-8061-3598-4. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ↑ "Tongue River, Montana Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ↑ "Map of the norther portion of the Tongue River Sandstone" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-02-12. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- 1 2 "Wyodak Coal, Tongue River Member of the Fort Union Formation, Powder River Basin, Wyoming, Mark Ashley, 2005". Archived from the original on 2006-10-12. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ↑ Tuholske, Jack. "Powder River Basin's Abundance of Coal at the Epicenter of Energy Development". Vermont Law Top 10 Environmental Watch List 2012. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ↑ "Wyodak Coal, Tongue River Member of the Fort Union Formation, Powder River Basin, Wyoming, Mark Ashley, 2005. See the map entitled "Depositional environment of Wyodak coal"". Archived from the original on 2006-10-12. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ↑ "Provenance of the Ludlow and Tongue River sand deposits, Fort Union formation (Paleocene) Southeastern Montana: Constraints on the Timing of the Big Horn uplift, Russell H. Abell" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-11-21. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ↑ Romeo m. Flores (October 22, 1979). "Coal Variations in Fluvial Deposition of Paleocene Tongue River Member of Fort Union Formation, Powder River Area, Wyoming and Montana: ABSTRACT". AAPG Bulletin. 63. doi:10.1306/2f91833d-16ce-11d7-8645000102c1865d. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ "Roadside Geology of Montana", Davit Alt and Donald K. Hyndman, 1986, Montana Press Publishing Company, p. 399-402

- ↑ Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, United States Army. Corps of Engineers; John Strong Newberry; William Franklin Raynolds (1869). Geological Report of the Exploration of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers: 1859–'60. Govt. Print. Off. p. 56. Archived from the original on 2017-04-07. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ Geological Report of the Exploration of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers: 1859–'60, by Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, United States Army. Corps of Engineers, John Strong Newberry, William Franklin Raynolds, Published by Govt. Print. Off., 1869, 174 pages, pp. 53, 55, 56

- ↑ "Abstract of Article by Valerie Tamm, A Comparison of Leaf Fossils from Upper Lebo and Lower Tongue River Members of the Fort Union Formation (Paleocene) near Locate Montana" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ "Restoring a History", Peter Nabokof and Lawrence L. Lowendorf, University of Oklahoma Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-8061-3589-2

- 1 2 "Road to Little Bighorn". www.friendslittlebighorn.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- 1 2 "Timeline and citations from Four Directions Institute".

- ↑ "Website discussing dog travois use by Crow, stating dog travois could carry up to 250 pounds". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ "Helena National Forest – Forest Prehistory". Archived from the original on 2012-06-30. Retrieved 2013-09-13.

- ↑ "Text of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, see Article 5 relating to the Crow lands". Archived from the original on 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Mark H (1959). The Plainsmen of the Yellowstone. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 128–129. ISBN 0-8032-5026-6.

- ↑ Text of Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, See Article 16, creating unceded Indian Territory east of the summit of the Big Horn Mountains and north of the North Platte River Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Opinions of the Solicitor of the Department of the Interior Relating to Indian Affairs, 1917–1974, United States Dept. of the Interior. Office of the Solicitor, Published by Wm. S. Hein Publishing, 2003, ISBN 9781575887555 pp. 1467 – 1470 Google Book Search. The 1884 order established the reservation, but the 1900 order confirmed arrangements to buy out non-Indians on the reservation and consolidated the Indians lands.

- 1 2 Devoto, Bernard (1998). Across the Wide Missouri. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-395-92497-6.

- ↑ Vestel, Stanley (1963). Joe Meek, the Merry Mountain Man. University of Nebraska Press. p. 152. ISBN 978-0-8032-5206-6.

- ↑ Devoto pp. 126–127

- ↑ "List of fur forts, citing 8 published authority sources for Ft. Van Buren". Archived from the original on April 19, 2016.

- ↑ See comments attributed to Glen Sweem in the history section in the Wikipedia article on Big Horn Wyoming.

- ↑ Brown, p. f46

- ↑ Fort Phil Kearney State Historic Site Archived 2008-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "The Bloody Bozeman', Dorothy M. Johnson, Montana Press Publishing Co. 1987, ISBN 0-87842-152-1, p. 159

- ↑ "The Bloody Bozeman', Dorothy M. Johnson, Montana Press Publishing Co. 1987, ISBN 0-87842-152-1, p. 165, 166

- ↑ "The Bloody Bozeman', Dorothy M. Johnson, Montana Press Publishing Co. 1987, ISBN 0-87842-152-1, p. 166, 167

- ↑ "The Fighting Cheyennes", George Bird Grinnell, Published by Digital Scanning Inc, 2004, ISBN 978-1-58218-390-9, p. 202.

- ↑ "The Bloody Bozeman', Dorothy M. Johnson, Montana Press Publishing Co. 1987, ISBN 0-87842-152-1, p. 195, 196

- ↑ Lubetkin, John M., Clash on the Yellowstone, Research Review, The Journal of the Little Big Horn Associates, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 12 – 32, Summer 2003

- ↑ "Battles and Skirmishes of the Great Sioux War, 1876–1877: The Military View", Jerome A. Greene, University of Oklahoma Press 1996, ISBN 978-0-8061-2669-2, p. 20 to 24.

- ↑ "Battles and Skirmishes of the Great Sioux War, 1876–1877: The Military View", Jerome A. Greene, University of Oklahoma Press 1996, ISBN 978-0-8061-2669-2, p. 25.

- ↑ Joseph De Barthe (1894). The Life and Adventures of Frank Grouard, Chief of Scouts, U.S.A. St. Joseph, Missouri: Combe Printing Company. pp. 266–292. ISBN 9780598278692. Archived from the original on 2017-04-06. Retrieved 2017-04-06.

- ↑ "Troopers with Custer: Historic Incidents of the Battle of the Little Big Horn", By E. A. Brininstool, J. W. Vaughn, Published by Stackpole Books, 1994, ISBN 978-0-8117-1742-7, pp.193–218.

- 1 2 Brown pp. 289–290

- ↑ "Battles and Skirmishes of the Great Sioux War, 1876–1877: The Military View", Jerome A. Greene, University of Oklahoma Press 1996, ISBN 978-0-8061-2669-2, p. 20 to 24

- ↑ "The Plainsmen of the Yellowstone: A History of the Yellowstone Basin" By Siringo Brown, Mark H. Brown, reissue, illustrated, Published by U of Nebraska Press, 1977, ISBN 978-0-8032-5026-0, pp. 293, 294

- ↑ Green, Jerome A. (1991). Yellowstone Command. University of Nebraska Press., Chapter 7

- ↑ "The Coal Mine Camps of Sheridan County Wyoming". Archived from the original on 2012-08-05. Retrieved 2009-01-19.

- ↑ "History of the Sheridan Railway Company". Archived from the original on 2010-09-18. Retrieved 2011-03-04.

- ↑ "Kiewit, description of Decker Coal Mine". Archived from the original on May 30, 2009.

- ↑ "State takes comment on Otter Creek coal application". Billings Gazette. December 9, 2014. Archived from the original on May 20, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ "The Plains Indians of the Twentieth Century", Peter Iverson, University of Oklahoma Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0-8061-1959-5, p. 226

- ↑ "Developments in Coal in 1985, SAMUEL A. FRIEDMAN, RICHARD W JONES, MARY L. W. JACKSON, COLIN G. TREWORGY, The American Association of Petroleum Geologists BulletinV. 70, No. 10(Octoberl986), P. 1643-1649".

- ↑ See "Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Fiscal Year 1910", U.S. Department of the Interior, p. 54, anticipating that coal deposits along the Tongue will result in construction of a railroad "in the near future".Google Book Search Archived 2020-08-20 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Malone, Michael P. (1991). Montana, A History of Two Centuries. University of Washington Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-295-97129-2.

- ↑ Malone, p. 184

- ↑ See description of the eradication of Wolves in the Wolf Mountains, "Big Sky, Big Horns and Things Great and Small", Chas. Kane, American Cowboy, May/June 1997, p. 49 Google Books Archived 2020-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ For photo of a leviathan catfish, caught at Tongue River Reservoir, see photo at the LandBigFish website Archived 2021-10-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Wyoming Fishing Network: The Tongue River". www.wyomingfishing.net. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ↑ "Stream Access in Montana". Archived from the original on March 10, 2009.

- ↑ "Where the Rivers Run North", Sam Morton, Sheridan County Historical Society Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9790841-0-2

- ↑ "A Bride Goes West", Nannie T. Alderson, Helena Huntington Smith, Re-published by U of Nebraska Press, 1969 ISBN 978-0-8032-5001-7

- ↑ Hell among the Yearlings, Edmund Randolph, Chicago: Lakeside Press 1978.