| Changxiao | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 長嘯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 长啸 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | long whistle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 장소 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 長嘯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 長嘯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | ちょうしょう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Chángxiào (Chinese: 長嘯; pinyin: chángxiào) or transcendental whistling was an ancient Daoist technique of long-drawn, resounding whistling that functioned as a qigong or transcendental exercise. A skillful whistler could supposedly summon animals, communicate with supernatural beings, and control weather phenomena. Transcendental whistling is a common theme in Chinese literature, for instance Chenggong Sui's (3rd century) Xiaofu 嘯賦 "Rhapsody on Whistling" and Ge Fei 's (1989) Hūshào 忽哨 "Whistling" short story. The most famous transcendental whistlers lived during the 3rd century, including the last master Sun Deng, and two of the eccentric Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, Ruan Ji and Ji Kang, all of whom were also talented zitherists.

Terminology

The Chinese language has two common words meaning "to whistle": xiào 嘯 or 啸 "whistle; howl; roar; wail" and shào 哨 "warble; chirp; whistle; sentry". Word usage of xiào 嘯 (first occurring in the c. 10th century BCE Shijing, below) is historically older than shào 哨 (first in the c. 2nd century BCE Liji describing a pitch-pot's "wry mouth").[1] Both Chinese characters are written with the mouth radical 口 and phonetic indicators of sù 肅 "shrivel; contract" and xiāo 肖 "like; similar". The 16-stroke character 嘯 has graphically simpler versions of 14-stroke 嘨 and 11-stroke 啸, and an ancient variant character xiao 歗 (with the yawn radical 欠).

Xiao

The etymology of Old Chinese *siûh 嘯 "to whistle: to croon" is sound symbolic, with cognates of Proto-Tibeto-Burman language *hyu or *huy "whistle" and Chepang language syu- "blow through (hand, etc.)".[2]

This same onomatopoeic and semantic sù < *siuk 肅 "shrivel; contract" element is also used to write xiāo 簫 "bamboo flute" (with the bamboo radical ⺮), xiāoxiāo 蕭蕭 "rustling sound (of falling leaves); whistling (of wind); whinnying (of horses)" (with the plant radical 艹), and xiāoxiāo 瀟瀟 "whistling (of wind) and pattering (of rain)" (with the water radical 氵).

The (121 CE) Shuowen Jiezi dictionary uses chuī 吟 "blow; puff; play (a wind instrument)" to explicate xiao; defining xiao 嘯 as 吹聲也 "to make sound by blowing", and xiao 歗 as 吟也 "to blow" (citing the Shijing 22, below).

The semantic field of xiào in Modern Standard Chinese includes human whistling and singing (for instance, xiàojiào 嘯叫 "whistle", yínxiào 吟嘯 "sing in freedom; lament; sigh", xiàogē 嘯歌 "sing at full voice"), whistling sounds (hūxiào 呼嘯 "whistle; scream; whiz (arrow)", xiàoshēng 嘯聲 "whistle; squeak; squeal; howl", hǎixiào 海嘯 "tsunami; tidal wave"), animal sounds (hǔxiào 虎嘯 "tiger's roar", yuánxiào 猿嘯 "monkey's cry", xiàodiāo 嘯雕 "whistling kite"), Daoistic counterculture (xiào'ào 嘯傲 "be forthright in speech and action; be leisurely and carefree", xiào'àoshānquán 嘯傲山泉 "lead a hermit's life in the woods and by a stream", xiàojù shānlín 嘯聚山林 "form a band and take to the forests"), and the present Daoist transcendental whistling (chángxiào 長嘯 "utter a long and loud cry; whistle", yǎngtiānchángxiào 仰天長嘯 "cry out at length to heaven; make a long throaty noise in the open air"). Donald Holzman says xiao "has a distracting range of meanings, clustered around the basic idea of 'producing sound through puckered lips', from the lion's roar to a man's whistling, passing through vocalization, chanting or wailing."[3]

The Hanyu Da Cidian unabridged Chinese dictionary defines two meanings for chángxiào 长啸 or 長嘯: 大声呼叫,发出高而长的声音 "Call out in a loud voice, issue a long, high-pitched sound", and 撮口发出悠长清越的声音 "Protrude the lips and issue a long, drawn-out, clear, and far-carrying sound".

While the English lexicon has diverse whistling vocabulary, such as whistled language and whistle register, it lacks a standard translation equivalent for Chinese changxiao, literally "long whistle/whistling". Direct translations fail to denote the word's supernatural aspects: "whistling without a break",[4] "long whistle",[5] "prolonged whistle",[6] and "long piercing whistle".[7] Explanatory translations are more meaningful to English readers; the commonly used "transcendental whistling" was coined by Victor Mair[8][9] and adopted by other authors (e.g., and many famous whistlers were xian "transcendents").[10] Some less common renderings are "cosmic 'whistling'",[11] "Taoist mediative [sic] whistle",[7] and "cosmic whistle".[12]

Shao

The semantic field of shào includes whistling sounds and whistle instruments (for instance, hūshào 呼/忽/唿哨 "to whistle", húshào 胡哨 "a whistle signal", kǒushào(r) 口哨 "a whistle (instrument and sound)", shàozi 哨子 "a whistle"), birds (niǎoshào 鳥哨 "birdcall", shàoyīng 哨鷹 "chanting goshawk", gēshào 鴿哨 "whistle tied to a pigeon"), and (whistle-signaling) guards (shàobīng 哨兵 "sentinel; sentry; guard", fàngshào 放哨 "to stand sentry", liàowàngshào 瞭望哨 "watchtower; lookout post").

The common "whistle" term hūshào (for which hū can be written 呼 "exhale; shout", 忽 "disdainful; sudden", or 唿 "sad") refers to a type of shrill, forceful finger whistling that is often mentioned in traditional Chinese short stories and novels of the Ming and Qing periods as a kind of remote signaling or calling.[13]

Textual examples

The Chinese classics provide a means of tracing the semantic developments of xiao from "wail", to "call back", to "whistle". The earliest usages in the Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 BCE) Shijing "Classic of Poetry" described the sound of women expressing high emotion or grief. The Warring States period (c. 475 – 221 BCE) Chuci "Songs of the South" used xiao and changxiao to mean a piercing whistle or call to summon back the spirit or a recently deceased person. The (1st century BCE) Liexian Zhuan "Collected Biographies of Transcendents" first associated transcendental whistling with Daoism, as represented by the Madman of Chu who mocked Confucius.

During the Eastern Han (25–220 CE) and Jin dynasty (266–420) xiao and changxiao whistling became especially associated with Daoism. For example, the Hou Hanshu (82)[14] biography of Xu Deng 徐登 mentions his companion Zhao Bing 趙柄 whistling to call up wind. "On another occasion, he was seeking passage across a river, but the boat man would not take him. [Bing] spread out a cloth and sat in the middle of it. Then with a long whistle he stirred up winds [長肅呼風] and whipped up wild currents which carried him across."

Later texts explain (chang)xiao transcendental whistling as a Daoist inner-breath qigong techniques. Daoist meditation and healing use a breathing technique called Liuqi fa 六氣法 "Method of the Six Breaths" that is practiced in various ways. The Six Breaths are si 嘶 "hissing with the lips wide and teeth together", he 呵 "guttural rasping with mouth wide open", hu 呼 "blowing out the breath with rounded lips", xu 嘘 "gently whistling with pursed lips", chui 吹 "sharply expelling the air with the lips almost closed", and xi 嘻 "sighing with mouth slightly open".[15]

Su calls the Six Dynasties (222–589) the "golden age of whistling". Xiao seems to have permeated all strata of Six Dynasties society, and practitioners included persons from almost all walks of life: recluses, hermit-scholars, generals, Buddhist monks, non-Chinese foreigners, women, high society elite, and Daoist priests. "In general, poets, hermits, and people of all types in the Six Dynasties utilized whistling to express a sense of untrammeled individual freedom, or an attitude of disobedience to authority or traditional ceremony, or to dispel suppressed feelings and indignation."[16]

Ancient superstitions about whistling continue in Chinese folklore. In the present day, some Han Chinese consider it taboo to whistle in the house at night for fear of provoking ghosts, and similarly, the minority Maonan people and Kam people (mostly in South Central China) believe that whistling while working in the fields will invoke demons to damage the harvest.[17]

Shijing

The earliest recorded textual usage of xiao 嘯 or 歗 meant "wail" not "whistle". Three (c. 10th-7th century BCE) Shijing "Classic of Poetry" odes use xiao to describe heartbroken women expressing sadness. Since the ancient, lyrical language of the Shijing can be difficult to interpret, the English translations of James Legge,[18] Arthur Waley,[19] and Bernhard Karlgren[20] are cited.

Two odes use xiao 嘯 along with gē 歌 "sing; song". Ode 22 江有汜 "The Yangzi Splits and Joins" is interpreted as concubines who were not allowed to accompany their bride to her new home, [江有沱]之子歸不我過 不我過其嘯也歌, translated as:

- Our lady, when she was married, would not come near us; Would not come near us, but she blew that feeling away, and sang.[21]

- Our lady that went to be married, Did not move us with her. She did not move us with her, But in the end she has let us come.[22]

- This young lady went to her new home, but she would not pass us on; She would not pass us on, but (now) crooningly she sings.[23]

Waley says the last words "are certainly corrupt" and suggests 宿也可 "allow to lodge". Karlgren explains "She can do nothing but croon (wail) and resign herself to it."

Ode 229 "White Flowers" uses xiaoge to describe a wife whose husband is gone, 嘯歌傷懷念彼碩人:

- I whistle and sing with wounded heart thinking of that great man.[24]

- Full of woe is this song I chant, Thinking of that tall man.[25]

- I (crooningly) wailingly sing with pained bosom, I am thinking of that tall man.[26]

These translators agree that ge means "sing; song" but differ over whether xiao means "whistle", "chant", and "croon; wail".

Ode 69 "In the Midst of the Valley are Motherworts" uses the graphic variant xiao 歗, interpreted as "groan", "sob", or "weep", describing another separated couple, 有女仳離條其嘯矣:

- There is a woman forced to leave her husband, Long-drawn are her groanings.[27]

- Bitterly she sobs, Faced with man's unkindness.[28]

- There is a girl who has been rejected; long-drawn-out is her (crooning:) wailing.[29]

Based on these Shijing contexts, Su says xiao means "to whistle" and is related to singing and chanting in general.[30]

Bernhard Karlgren's detailed Shijing gloss concludes xiao means "wail; groan" instead of "whistle".[31] The Han version commentary says xiao means 歌無章曲 "to sing without stanzas or (fixed) melody, i.e., "to croon", thus "When she croons she sings" = "crooningly she sings"; Zheng Xuan's commentary to the Mao version says it means 蹙口而出聲 "to compress the mouth and emit a sound", i.e., "to whistle", "When she whistles she sings (=) she whistles and sings". Zhu Xi says xiaohu 嘯呼 means sù or sòu 嗖 "wail; whiz". Karlgren notes that xiao can mean either "to whistle" or "to croon; to wail"; citing the Liji 不嘯不指 "He does not whistle, nor point with the finger" and Huainanzi 黃神嘯吟 "The yellow spirit wails and moans".

Like the Shijing, Han and Six Dynasties texts frequently associated whistling with women expressing their sorrows. The Lienu zhuan "Biographies of Exemplary Women"[32] has a story about a secretly wise "Girl from Qishi 漆室 in Lu" (modern Zoucheng, Shandong). The girl was leaning against a pillar and whistling [倚柱而嘯]. Her neighbor heard and asked if she was whistling sadly because she longed for a husband, which the neighbor offered to arrange. The girl answered that she was not worried about getting a husband, but was worried because the ruler of Lu was old and but the crown prince was still too young. As the girl feared, Lu fell into chaos and was invaded by neighboring states.

Chuci

The (c. 3rd century BCE – 2nd century CE) Chuci "Songs of Chu" uses xiao to mean "call back (a dead person's soul)", monkey and tiger "calls; roars", and "whistle; call out".

The earliest textual example of xiao meaning "to summon a spirit" is in the Zhaohun "Summons of the Soul", which describes a shamanistic ritual to resuscitate a recently deceased person by calling back their hun "spiritual soul that leaves the body after death", as opposed to their po "corporal soul that remains with the deceased corpse". This poem uses the compound xiàohū 嘯呼 with "shout; call"

O soul, come back! And enter the gate of the city. Skilled priests are there who call you, walking backwards to lead you in. Qin basket-work, silk cords of Qi, and silken banners of Zheng: All things are there proper for your recall; and with long-drawn, piercing cries they summon the wandering soul [永嘯呼些]. O soul, come back! Return to your old abode.[33]

Wang Yi’s commentary invokes yin and yang theory. "Xiao has yin characteristics, and hu has yang characteristics. Yang governs the hun spiritual soul, and yin governs the po animal soul. Thus, in order to summon the whole being, one must xiaohu. Karlgren translates "Long-drawn I (croon:) wail".[31] David Hawkes notes that the Yili ritual handbook section on zhaohun "soul-summoning" does not mention the shamanistic xiao "whistling" found in the Chuci, and suggests that the Confucian ritualist who compiled the text "evidently did not expect this somewhat perfunctory soul-summoning to be successful."[34] The Yili says the soul-summoner should take a suit of clothing formerly worn by the deceased, climb a ladder to the roof, stretch out the clothes, get up on the roof ridge, and "call out three times in a loud voice, 'Ho, Such a One! Come back!" Then he hands the clothing down to an assistant, who puts it on the corpse for viewing, and then the summoner climbs back down.

Zhaoyinshi "Summons for a Recluse" uses xiao describing the calls of yuanyou 猿狖 "gibbons".

The cassia trees grow thick In the mountain's recesses, Their branches interlacing. The mountain mists are high, The rocks are steep. In the sheer ravines The waters' waves run deep. Monkeys in chorus cry; Tigers and leopards roar [猿狖群嘯兮虎豹原]. One has climbed up by the cassia boughs Who wishes to tarry there.[35]

Miujian "Reckless Remonstrance" uses xiao for a tiger's "roar", among examples of ganying "correlative resonance".

Like sounds harmonize together; Creatures mate with their own kind. The flying bird cries out to the flock; The deer calls, searching for his friends. If you strike gong, then gong responds; If you hit jue, then jue vibrates. The tiger roars, and the wind of the valley comes [虎嘯而谷風至兮]; The dragon soars, and the radiant clouds come flying.[36]

Sigu "Sighing for Olden Times", which is attributed to the Chuci editor Liu Xiang, uses xiao meaning "whistle; call out".

I think how my homeland has been brought to ruin, And the ghosts of my ancestors robbed of their proper service. I grieve that the line of my father's house is broken; My heart is dismayed and laments within me. I shall wander a while upon the sides of the mountain, And walk about upon the river's banks. I shall look down, whistling, on the deep waters [臨深水而長嘯兮], Wander far and wide, looking all about me.[37]

Huainanzi

Liu An's (c. 139 BCE) Huainanzi "Masters of Huainan", which is a compendium of writings from various schools of Chinese philosophy, has two xiao "howl; wail; moan" usages, which clearly exclude "whistle".[38]

The "Celestial Patterns" chapter uses xiao "roar" in a context giving examples of yin-yang ganying resonance, including the Chinese sun and moon mirrors yangsui 陽燧 "burning mirror" and fangzhu 方諸 "square receptacle".

Fire flies upward; water flows downward. Thus, the flight of birds is aloft; the movement of fishes is downward. Things within the same class mutually move one another; root and twig mutually respond to each other. Therefore, when the burning mirror sees the sun, it ignites tinder and produces fire. When the square receptacle sees the moon, it moistens and produces water. When the tiger roars, the valley winds rush [虎嘯而穀風至]; when the dragon arises, the bright clouds accumulate. When qilins wrangle, the sun or moon is eclipsed; when the leviathan dies, comets appear. When silkworms secrete fragmented silk, the shang string [of a stringed instrument] snaps. When meteors fall, the Bohai surges upward. (3.2)[39]

The Huainanzi "Surveying Obscurities" chapter uses xiao "moan" referring to people suffering under the legendary tyrant Jie of Xia.

Beauties messed up their hair and blackened their faces, spoiling their appearance. Those with fine voices filled their mouths with charcoal, kept their [talent] shut away, and did not sing. Mourners did not [express] the fullness of grief; hunters did not obtain any joy [from it]. The Western Elder snapped her hair ornament; the Yellow God sighed and moaned [黃神嘯吟]. (6.)[40]

The honorific names Xilao 西老 "Western Elder" and Huangshen 黃神 "Yellow God" refer to the Queen Mother of the West and Yellow Emperor.

Liexian zhuan

The Daoist Liexian Zhuan "Collected Biographies of Transcendents", edited by Liu Xiang (c. 79–8 BCE), uses changxiao in the hagiography of Lu Tong 陸通 (better known as Lu Jieyu, or Jie Yu 接輿, the madman of Chu).

The story of Lu Jieyu meeting Confucius (551–479 BCE) is well known. The first version is in the Confucian Lunyu.

Chieh Yü, the madman of Ch'u, came past Master K'ung, singing as he went: "Oh phoenix, phoenix How dwindled is your power! As to the past, reproof is idle, But the future may yet be remedied. Desist, desist! Great in these days is the peril of those who fill office." Master K'ung got down [from his carriage], desiring to speak with him; but the madman hastened his step and got away, so that Master K'ung did not succeed in speaking with him.[41]

The Daoist Zhuangzi gives an anti-Confucian version.

When Confucius went to Ch'u, Chieh Yü, the madman of Ch'u, wandered about before his gate, saying: "Phoenix! Oh, Phoenix! How your virtue has declined! The future you cannot wait for, The past you cannot pursue. When the Way prevails under heaven, The Sage seeks for accomplishment; When the Way is absent from the world, The sage seeks but to preserve his life. In an age like that of today, All he can hope for is to avoid punishment. …"[42]

The Liexian zhuan entry about the feigned "madman" says.

Lu Tong was the madman of Chu, Jieyu. He loved nourishing life, his food was beggarticks, wax-myrtles, and turnips. Lu traveled to famous mountains, and was sighted over many generations on the peak of Mount Emei, where he lived for several hundred years before departing. Jieyu delighted in talking about nourishing the inner nature and concealing one's brilliance. His custom was to mock Confucius, and proclaim a decline in [the virtue of] the phoenix. He matched breaths with harmony and cherished the abstruse. He strode across lofty mountains, and transcendentally whistled on Mount Emei. [陸通者雲楚狂接輿也 好養生食橐廬木實及蕪菁子 游諸名山在蜀峨嵋山上世世見之歷數百年去 接輿樂道養性潛輝 風諷尼父諭以鳳衰 納氣以和存心以微 高步靈岳長嘯峨嵋]

Xiaofu

The Xiaofu 嘯賦 "Rhapsody on Whistling" was written by Chenggong Sui 成公綏 (231–273), a renowned Jin dynasty (266–420) author of fu "rhapsody; poetic exposition" rhymed prose. The Heian period scholar-official Sugawara no Kiyotomo's (814) Ryōunshū poetry collection includes his Japanese Shōfu 嘯賦 "Rhapsody on Whistling".[43]

The (648) Book of Jin (92) biography of Chenggong Sui is the primary source about his life and writing the prose-poem Xiaofu. Sui, whose courtesy name was Zi'an 子安, was a native of Boma 白馬 in the Eastern Commandery 東郡 (present day Hua County, Henan). As a youth, he read widely in the classics, and had a great talent for writing beautiful fu. Sui especially loved musical temperament [音律]. Once during hot weather, he received instruction/enlightenment from the wind and whistled [承風而嘯], making his tune cool and clear [泠然成曲]. Following this, he composed the Hsiao fu [… quoting full text]. The poet-official Zhang Hua regarded Chenggong Sui's writings as peerless and recommended him as an official. Sui served as Chancellor to the Minister of Ceremonies and Palace Writer Attendant. He died in 273 at the age of 43.

The Rhapsody on Whistling begins with an idealized recluse who retires from the world with a group of friends to learn Daoist secrets through techniques of transcendental whistling, with which the whistler expresses his disdain toward the vulgar world, and releases his indignation and suffering.[44]

The secluded gentleman, In sympathy with the extraordinary, And in love with the strange, Scorns the world and is unmindful of prestige. He breaks away from human endeavor and leaves it behind. He gazes up at the lofty, longing for the days of old; He ponders lengthily, his thoughts wandering afar. He would Climb Mount Chi, in order to maintain his moral integrity; Or float on the blue sea to wander with his ambition.

So he invites his trusted friends, Gathering about himself a group of like-minded. He gets at the essence of the ultimate secret of life; He researches the subtle mysteries of Tao and Te. He regrets that the common people are not yet enlightened; He alone, transcending all, has prior awakening. He finds constraining the narrow road of the world – He gazes up at the concourse of heaven, and treads the high vastness. Distancing himself from the exquisite and the common, he abandons his personal concerns; Then, filled with noble emotion, he gives a long-drawn whistle [乃慷慨而長嘯].

Thereupon, The dazzling spirit inclines its luminous form, Pouring its brilliance into Vesper's Vale. And his friends, rambling hand in hand, Stumble to a halt, stepping on their toes. He sends forth marvelous tones from his red lips, And stimulates mournful sounds from his gleaming teeth. The sound rises and falls, rolling in his throat. The breath rushes out and is repressed, then flies up like sparks [氣衝鬱而熛起]. He harmonizes [the notes of the Chinese pentatonic scale] 'golden kung' with 'sharp chiao,' Blending shang and yü into 'flowing chih.' The whistle floats like a wandering cloud in the grand empyrean, And gathers a great wind for a myriad miles. When the song is finished, and the echoes die out, It leaves behind a pleasure that lingers on in the mind. Indeed, whistling is the most perfect natural music, Which cannot be imitated by strings or woodwinds.

Thus, the Whistler Uses no instrument to play his music, Nor any material borrowed from things. He chooses it from the near-at-hand—his own Self, And with his mind he controls his breath [役心御氣]. [45]

In this context, Mair notes that shen 身 "body; person" means "Self" in the sense of Daoist meditation.[46] "The whistler finds the music and the means of producing it within himself … Everything is available within the Self. The breath and the mind are closely linked. By cultivating the flow of his attention, he simultaneously gains control over the flow of his breath."

The Rhapsody then elaborates on transcendental whistling. It spontaneously harmonizes with the world, "For every category he has a song; To each thing he perceives, he tunes a melody."; "Thus, the Whistler can Create tones based on the forms, Compose melodies in accordance to affairs; Respond without limit to the things of Nature".[47] The marvelous sounds affect both the whistler, "Pure, surpassing both reed and mouth-organ; Richly harmonious with lute and harp. Its mystery is subtle enough to unfold fully pure consciousness and enlighten creative intelligence."; and the listener, "Though you be lost in thoughts, it can bring you back to your Mind; Though you be distressed, it will never break your Heart".[48]

Should he then Imitate gong and drum, or mime clay vessels and gourds; here is a mass of sound like many instruments playing – Like reed pipe and flute of bamboo [xiao 簫] – Bumping boulders trembling, An horrendous crashing, smashing, breaking. Or should he Sound the tone chih, then severe winter becomes steaming hot; Give free play to yü, then a sharp frost makes summer fade; Move into shang, then a long autumn rain appears to fall in springtime; Strike up the tone chiao, then a vernal breeze soughs in the bare branches.[49]

Chenggong Sui obviously understood the technical aspects of the pentatonic scale and the relationship of musical notes and pitch standards.[50]

The Rhapsody on Whistling concludes by describing famous musicians, singers, and animals all enthralled by hearing the whistler's performance, and uses changxiao again, "They understand the magnificent beauty of the long-drawn Whistle [乃知長嘯之奇妙]; Indeed, this is the most perfect of sounds".[51]

This prose-poem has many Daoist elements besides researching "the subtle mysteries of Tao and Te" (above). Transcendental whistling is presented as a powerful method of self-cultivation through breath control. The statement that "with his mind he controls his breath" uses the Daoist term yùqì 御氣 "control the breath; move qi through the body", further described as,

The [eight] sounds and [five] harmonies constantly fluctuate; The melody follows no strict beat. It runs, but does not run off. It stops, but does not stop up. Following his mouth and lips, he expands forth. Floating on his fragrant breath, he wanders afar [假芳氣而遠逝]. The music is, in essence, subtle with flowing echoes. The sound races impetuously, but with a harsh clarity. Indeed, with its supreme natural beauty, It is quite strange and other-worldly.[51]

Fangqi 芳氣 "fragrant breath" is a Daoist metaphor for meide 美德 "beautiful virtues".

Shenxian zhuan

Ge Hong's (c. 4th century) Daoist Shenxian zhuan "Biographies of Divine Transcendents" has two hagiographies that mention supernatural whistling powers; Liu Gen 劉根 could summon ghosts, and Liu Zheng 劉政 could summon powerful winds.

First, the hagiography of the Han dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) fangshi Liu Gen 劉根 says he saved himself from punishment by changxiao whistling to summon the prosecutor's family ghosts who insisted on his freedom.

Liu Gen, styled Jun'an 君安, was a native of the capital at Chang'an. As a youth he understood the Five Classics. During the second year of the suihe period of Han Emperor Cheng's reign [7 BCE], he was selected as a Filial and lncorrupt and was made a Gentleman of the Interior. Later he left the world behind and practiced the Way. He entered a cave on Mount Songgao that was situated directly above a sheer cliff over fifty thousand feet high. Winter or summer, he wore no clothing. The hair on his body grew one to two feet long. … Commandant Zhang, the new governor, took Liu Gen to be a fake, and he sent lictors to summon him, plotting to have him killed. … The commandant ordered over fifty men brandishing swords and pikes to tie Liu up and stand him at attention. Liu's face showed no change in color. The commandant interrogated Liu as follows: "So, do you possess any arts of the Dao?" "Yes." "Can you summon ghosts?" "I can." "Since you can," said the commandant, "you will bring ghosts before this chamber bench at once. If you do not, I will have you tortured and killed." Liu replied, "Causing ghosts to appear is quite easy." Liu Gen borrowed a brush and an inkstone and composed a memorial. [In a moment,] a clanging sound like that of bronze or iron could be heard outside, and then came a long whistling sound, extremely plangent [因長嘯嘯音非常清亮]. All who heard it were awestruck [聞者莫不肅然], and the visitors all shook with fear. In another moment, an opening several dozen feet wide appeared in the south wall of the chamber, and four hundred or five hundred armored troops could be seen passing orders down the lines. Several dozen crimson-clad swordsmen then appeared, escorting a carriage straight through the opened wall into the chamber. The opened wall then returned to its former state. Liu Gen ordered the attendants to present the ghosts. With that, the crimson-clad guards flung back the shroud covering the carriage to reveal an old man and an old woman tightly bound inside. They hung their heads before the chamber bench. Upon examining them closely, the commandant saw that they were his deceased father and mother. Shocked and dismayed, he wept and was completely at a loss. The ghosts reprimanded him, saying, "When we were alive, you had not yet attained office, so we received no nourishment from your salary. Now that we are dead, what do you mean by offending a venerable official among divine transcendents and getting us arrested? After causing such a difficulty as this, aren't you ashamed even to stand among other people?" The commandant came down the steps and knocked his head on the ground before Liu Gen, saying that he deserved to die and begging that his ancestors be pardoned and released. Liu ordered the five hundred troops to take out the prisoners and release them. As the carriage moved out, the wall opened back up; then, when it was outside, the wall closed again and the carriage was nowhere to be seen. Liu had also disappeared.[52]

Robert Ford Campany notes, "The whistlers may be not the ghosts of the departed but the spirit-officials who are ushering them along. Esoteric techniques of whistling numbered among Daoist arts."

In the History of the Latter Han version of this story, it is Liu Gen himself who does the xiao rather than changxiao whistling.

Liu Gen was a native of Yingchuan. He dwelt in seclusion on Mount Song. Curiosity seekers came from afar to study the Dao with him. The Governor Shi Qi 史祈 took him for a charlatan and had him arrested and brought in to his offices. He questioned him, saying, "What arts do you have, that you mislead and deceive the people so? You will perform a confirmatory feat, or else you will die at once." Liu said, "I truly have no unusual powers, except that I have some small ability to cause people to see ghosts." "Summon one right now," Shi said, "so that I can see it with my own eyes, and only then will I take it as clearly established." At this, Liu Gen looked to the left and whistled [左顧而嘯]. In a moment, Shi's deceased father, along with several dozen of his departed relatives, appeared before them, bound. They knocked their heads on the ground toward Liu and said, "Our son has acted wrongly and should be punished!" Then they turned to Shi Qi and said, "As a descendant, not only do you bring no benefit to your ancestors, but you bring trouble to us departed spirits! Knock your head on the ground and beg forgiveness for us!" Shi Qi, stricken with fear and remorse, knocked his head until it ran blood and begged to take the punishment for his crime himself Liu Gen remained silent and made no reply. Suddenly he [and the ghosts] all vanished.[53]

Second, the hagiography of Liu Zheng 劉政, who lived to an age of more than 180 years, uses chuīqì 吹氣 "blow one's breath" to mean "whistle up (wind)".

Liu Zheng was a native of Pei. He was highly talented and broadly learned; there was little his studies had not covered. … He lived for more than one hundred eighty years, and his complexion was that of a youth. He could transform himself into other shapes and conceal his form … Further, he was capable of planting fruits of all types and causing them immediately to flower and ripen so as to be ready to eat. He could sit down and cause the traveling canteen to arrive, setting out a complete meal for up to several hundred people. His mere whistling could create a wind to set dust swirling and blow stones about [能吹氣為風飛沙揚石]. By pointing his finger he could make a room or a mountain out of a gourd; when he wanted to tear it down, he simply pointed again, and it would become as before. He could transform himself into the form of a beautiful woman. He could create fire and water, travel several thousand li in a single day, create clouds by breathing over water, and make fog by raising his hands.[54]

Shishuo xinyu

The (5th century) Shishuo Xinyu version of this whistling story about Ruan Ji visiting the unnamed Sun Deng, referred to as the zhenren "perfected person" in the Sumen Mountains 蘇門山.

When Juan Chi whistled [嘯], he could be heard several hundred paces away. In the Su-men Mountains (Honan) there appeared from nowhere a Realized Man [真人] about whom the woodcutters were all relaying tales. Juan Chi went to see for himself and spied the man squatting with clasped knees by the edge of a cliff. Chi climbed the ridge to approach him and then squatted opposite him. Chi rehearsed for him briefly matters from antiquity to the present, beginning with an exposition of the Way of Mystical Quiescence [玄寂] of the Yellow Emperor and Shen Nung, and ending with an investigation of the excellence of the Supreme Virtue [盛德] of the Three Ages (Hsia, Shang, and Chou). But when Chi asked his opinion about it he remained aloof and made no reply. Chi then went on to expound that which lies beyond Activism [有為之教], and the techniques of Resting the Spirit [棲神] and Conducting the Vital Force [導氣]. But when Chi looked toward him for a reply, he was still exactly as before, fixedly staring without turning. Chi therefore turned toward him and made a long whistling sound [長嘯]. After a long while the man finally laughed and said, "Do it again." Chi whistled a second time [復嘯], but as his interest was now exhausted, he withdrew. He had returned about half-way down the ridge when he heard above him a shrillness like an orchestra of many instruments, while forests and valleys reechoed with the sound. Turning back to look, he discovered it was the whistling of the man he had just visited [向人嘯]. (49)[55]

Holzman says that when Ruan Ji whistles, Sun Deng realizes that he is "not merely a pedant, but also an adept of an art that imitates nature, that he is able to control his breath so as to make it resemble that very breath of heaven."[56]

The Shishuo xinyu commentary by Liu Xiaobiao quotes two texts. First, the (4th century) Wei Shi Chunqiu 魏氏春秋 version says,

Juan Chi often went riding alone wherever his fancy led him, not following the roads or byways, to the point where carriage tracks would go no farther, and always he would return weeping bitterly. Once while he was wandering in the Su-men Mountains there was a recluse living there whose name no one knew, and whose only possessions were a few hu-measures of bamboo fruit, a mortar and pestle, and nothing more. When Juan Chi heard of him he went to see him and began conversing on the Way of Non-action [無為] of high antiquity, and went on to discuss the moral principles [義] of the Five Emperors and Three August Ones. The Master of Su-men remained oblivious and never even looked his way. Chi then with a shrill sound made a long whistling whose echoes reverberated through the empty stillness. The Master of Su-men finally looked pleased and laughed. After Chi had gone down the hill, the Master gathered his breath and whistled shrilly with a sound like that of the phoenix. Chi had all his life been a connoisseur of music, and he borrowed the theme of his discussion with the Master of Su-men to express what was in his heart in a song, the words of which are: "The sun sets west of Mt. Pu-chou; The moon comes up from Cinnabar Pool. Essence of Yang is darkened and unseen; While Yin rays take their turn to win. His brilliance lasts but for a moment; her dark will soon again be full. If wealth and honor stay but for a trice must poverty and low estate be evermore?"[57]

Second, the Zhulin Qixian Lun 竹林七賢論,[58] by Dai Kui 戴逵 (d. 396) explains, "After Juan Chi returned (from the Su-men Mountains) he proceeded to compose the "Discourse on Mr. Great Man" [大人先生論]. What was said in this discourse all represented the basic feelings in his breast and heart. The main point was that Mr. Great Man was none other than Juan himself."

In addition, the Shishuo xinyu biography of Liu Daozhen 劉道真 says he was "good at singing and whistling [善歌嘯]".

Jin shu

Two chapters in the (648) Book of Jin record the meeting between Ruan Ji and Sun Deng.

Ruan Ji's biography (in chapter 49, Biographies) uses changxiao and xiao to describe his visit with Sun Deng.

Once [Juan] Chi met Sun Teng on Su-men Mountain [蘇門山]. [Juan Chi] touched on topics of ancient times, and on the arts of "posing the spirit" and "leading the breath" [棲神導氣之術]. [Sun] Teng kept silent throughout. As a result, [Juan] Chi expelled a long whistle [籍因長嘯而退], and took his leave. When he had descended halfway down the mountain, he heard a sound like the cry of the phoenix resounding throughout the peaks and valleys. It was the whistling of [Sun] Teng [乃登之嘯也].[59]

Varsano explains this transcendental whistling as a direct representation of the ineffable Dao, "his superhuman whistle, a primordial sound that does not describe the secrets of the universe, but incarnates it."[60]

Sun Deng's biography (94, Hermits and Recluses) does not mention xiao whistling, but this chapter uses xiao in the biography of Tao Qian 陶潛 [登東皋以舒嘯] and changxiao in that of Xia Tong 夏統 [集氣長嘯]. The Jin shu account of Sun Deng says,

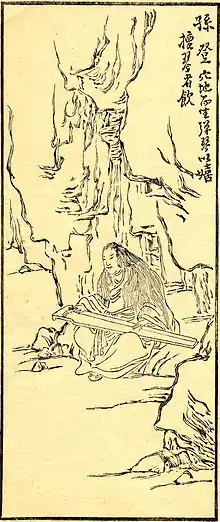

Sun Teng, whose tzu was Kung-ho [公和], was a man of Kung in Chi commandery. He was homeless, but stayed in the mountains in the north of the commandery where he lived in a cavern in the earth that he had made for himself. In summer he wove grasses to wear as a shirt and in winter he let his hair down to cover himself. He liked to read the I ching and played a one-stringed zither [一絃琴]. All those who saw him felt friendly towards him and took pleasure in his company. There was not an ounce of hatred or anger in him. He was one thrown into the water to arouse his anger, but he just came out and broke into an enormous guffaw. From time to time he would wander among men and some of the householders he passed would set out food and clothing for him, now of which he would keep: when he had taken his leave he threw them all away. Once when he went to the mountains at I-yang [宜陽山] he was seen by some charcoal burners who knew he was not an ordinary man. But when they talked to him, he did not answer. Wen-ti [Ssu-ma Chao] heard about it and sent Juan Chi to investigate.[61]

The context goes on to say that after Sun Deng refused to talk with Ruan Ji, Xi Kang followed Sun Deng travelling for three years. Since Sima Zhao became generalissimo in 255, Holzman dates Ruan Ji's visit around 257, and Xi Kang's around 258 to 260. Based on the different mountain names, Chan says Ruan Ji visited Sun Deng twice, first around 226-230, and then around 255-263; and dates Xi Kang's travels at around 249–251.[62]

The Jinshu biography of Liu Kun 劉琨, the Governor of Bingzhou 并州 (modern Shanxi), records that once when the capital Jinyang was under siege by an army of Xiongnu cavalry, Liu supposedly ended the siege by giving a qingxiao 清嘯 "clear whistle" and playing a hujia "a Mongolian double-reed instrument". "Liu Kun ascended a tall building by moonlight and emitted a clear xiao [清嘯]. When the Xiongnu soldiers heard it, they sighed sadly. In the middle of the night he played the hujia [a kind of oboe originating on the steppes, perhaps the predecessor of the suona]; the Xiongnu became homesick on hearing it. He played again at dawn and he Xiongnu lifted the siege and left".[63]

Xiaozhi

The anonymous (c. 8th century) Xiaozhi 嘯旨 "Principles of Whistling" is included in several collections of Tang dynasty literature, such as the Tangdai congshu 唐代叢書. According to the (c. 800) Fengshi wenjian ji 封氏聞見記, written by Feng Yan 封演, the Xiaozhi was written in 765 by a judge Sun Guang 孫廣, who is otherwise unknown. The titular word zhǐ 旨 means "intention; aim; meaning", and the translator E. D. Edwards says the text is about "How to Whistle".[64] Paul W. Kroll translates Xiaozhi as "Directives on Whistling".[65]

There are two theories regarding the origin of the "Principles of Whistling".[66] The first is that during the Six Dynasties (220–589) period, some people opposed to Confucianism went into the mountains and did what they liked, including as, for example whistling, since Confucius looked down on those who whistled (e.g., Liji). The other is the Daoist theory, which is more probable since the Xiaozhi frequently mentions Dao. The Daoists believed that breathing the breath of Nature was one means of gaining immortality, and by whistling they were breathing in accord with Nature, and therefore they came nearer to Immortality.

The Xiaozhi Preface begins with a definition that semantically expands xiao from "moan; call out" and "call back (a soul)" to a new meaning of "communicating (with the Daoist gods and spirits)".

Air forced outwards from the throat and low in key is termed speech; forced outwards from the tongue and high in key is termed hsiao (whistling). The low key of speech is sufficient for the conduct of human affairs, for the expression of our natural feelings; the high key of whistling can move supernatural beings and is everlasting. Indeed, though a good speaker can win response from a thousand li, a good whistler commands the attention of the whole world of spirits.[67]

Donald Holzman translates this as "a sound produced by breath striking against the tip of the tongue … a method of communicating with the spirits and achieving immortality", and comments, "Whatever whistling did signify, the important thing to note is that it was an unintellectual art, probably a fairly strange kind of sound divorced from speech and reason."[56]

The Preface then outlines a Daoist mytho-history of xiao transmission.

Laozi transmitted it to Queen Mother of the West, she to the Perfected Person of the South Polar Star 南極真人 [controller of human longevity], he to Guangchengzi, he to the wind god Feng Bo, and he to Xiaofu 嘯夫 Father of Whistling. Father of Whistling taught it to [7-inch-tall] Wu Guang 務光, he to Emperor Yao, and Yao to Emperor Shun, who invented the zither. Shun transmitted whistling to Yu the Great, after whom the art declined until it was revived by the Jin dynasty (266–420) Daoist transcendent Sun Gong 孫公 of Mt. Taihang who obtained the technique, achieved the Way, and disappeared without teaching it to anyone. Ruan Ji had a smattering knowledge of the art but after him it was lost and no longer heard.[68]

The Shanhaijing says, "In appearance, Queen Mother of the West looks like a human, but she has a leopard's tail and the fangs of a tigress, and she is good at whistling. She wears a victory crown on her tangled hair."[69] The Shanghaijing using xiao for the tiger-like Queen Mother's "whistling" parallels the Huainanzi using it for a tiger's "howl".[70] The Liexian Zhuan lists the Father of Whistling, who could control fire, but does not mention whistling.

The Xiaozhi 嘯旨 has fifteen sections. Section 1 "First Principles" tells how to practice whistling, for instance, "regulate the respiration, correct the relative positions of lips and teeth, compose the sides of the mouth, relax the tongue, practise in some retired spot." It also gives twelve specific whistling techniques, such as,[71] Waiji 外激— "Place the tongue in close contact with the inside of the upper teeth. Open wide both lips and force the breath outwards, letting the sound go out."; and Neiji 內激—"Place the tongue as before; close both lips, compressing them to a point, like the opening of a stalk of wheat. Pass the breath through, making the sound go inwards."

Titles of subsequent sections are either poetic descriptions of tunes, e.g., "Tiger in a Deep Ravine" (3), "Night Demons in a Lonely Wood" (5), and "Snow Geese and Swans Alighting" (7); or references to famous historical whistlers, e.g., "Su Men [Mountains]" (11) was transmitted by Sun Deng, and "The Loose Rhymes of Ruan" was composed by Ruan Ji (both mentioned above). The Xiaozhi explains and describes each whistling tune. Take, for example, "Su Men", which retells the story of Sun Deng and Ruan Ji (above), but with whistling instead of zither playing.

The 'Su Men' was composed by the Taoist Immortal Recluse, who lived in the Su Men Mountains (of Honan). The Holy One transmitted, he did not make it. The Immortal transmitted (the music of) Kuang Ch'eng and Wu Kuang 務光 in order to rejoice the spirit and expand the Tao. He did not regard music as the main task. In olden days there were those who roved in Su Men listening to the phoenix' songs. The notes were exquisitely clear, very different from the so-called pretended phoenix. The phoenix makes sounds but humans cannot hear them. How then can the Su Family know the sound of the phoenix? Hereafter, when seeking the sound, bring up the Immortal's whistle. The Immortal's whistle does not stop at fostering the Tao and gratifying the spirits; for indeed, in everyday affairs it brings harmony into the world, and peace in season. In oneself the Tao never dies, in objective matters it assists all that is sacred, and conducts the Five Influences. In the arcana of Nature order prevails. For success in obtaining response (to such efforts) nothing approaches music. The Immortal has evolved the one successful form. As to all wild things whistling is the one thing needful. Yuan Szu-tsung of Chin (Yuan Chi) was a fine whistler. Hearing that the Immortal thought himself his equal, he (Yuan) went to visit him. The Immortal remained seated with his hair in disorder. Yuan bowed repeatedly and inquired after his health. Thrice and again thrice he addressed his (uncivil) host. The Immortal maintained his attitude and made no response. Chi then whistled some score of notes and left. The Immortal, estimating that his guest had not gone far, began to whistle the Ch'ing Chueh [清角] to the extent of four or five movements. But Chi perceived that the mountains and all growing things took on a different sound. Presently came a fierce whirlwind with pelting rain, followed by phoenixes and peacocks in flocks; no one could count them. Chi was alarmed, but also pleased, and he returned home and wrote down the story. He obtained only two-tenths of it, and called it 'Su Men'. This is what they tell there. The motif of the song is lofty mountains and wide marshes, great heights and distances.[72]

The Xiaozhi explains the essence of xiao whistling in the "Fleeting Cloud" (section 6),[73] "The lute suits southern manners; the reed-organ suits the cry of the phoenix; the fife suits the dragon's drone. Every musical sound has its counterpart (in nature). So, the roar of the tiger and the drone of a dragon all have a proper sequence of notes." Transcendental whistling evokes the sounds of nature. Ronald Egan describes changxiao as "a well-known method, associated with Taoist practices, by which the devotee prepares his own mind for the experience of nature and, simultaneously, attempts to elicit a sympathetic reaction" from nature".[6]

"Standard Notes" (14)[74] mentions Daoist immortality, "In comparatively modern days, Sun Kung [Sun Deng] was successful, but people did not listen. As to peaceful notes [平和], they stave off old age and do not allow one to die. These Standard notes are known about, but the notes themselves are lost." The last "Conclusion" section (15)[75] says, "The conclusion is at the extremities of the [pentatonic] scale, the end of the Great Tao. After the days of Yao and Shun there was some idea of these notes, but the actual notes were lost." The Conclusion includes a (1520) colophon written by Ming dynasty scholar Geng Chen, who describes the book as exceedingly rare, and probably written by someone during the Tang dynasty.

The preface says, "the (Western) Queen Mother taught the Fairy of the South Polar Star; he passed it on to Kuang Ch'eng-tzu". This is extravagant talk, and not usually accepted. But the twelve methods are found in Sun Teng and Yuan Chi [i.e., Ruan Ji], so that we can truly say we have the general purport of Whistling. The Preface also says that Sun Teng did not hand on (the gift) to anyone, and after Yuan Chi it disappeared and was no more heard. … Now the voice of man is the voice of the universe (nature). Man may be ancient or modern, but sound is eternal, never new or old. Now this book is going forth and who knows whether a Sun or Yuan may not appear in some mountains or woods and, that being so, who can say that there is an end to Whistling?[76]

The Xiaozhi houxu 肅旨後序 "Postface to the Principles of Whistling", written by the Ming dynasty scholar and artist Tang Yin (1470–1524), compares the non-verbal art of xiao whistling with a Daoist priest's secret incantation and a Buddhist monk's magical formula in Sanskrit.[77]

Tang poetry

Tang poetry is renowned in history of Chinese literature. Kroll says many medieval poems mention changxiao "long whistling", but translators generally convert it into a dull "humming."[65]

In the extensive Complete Tang Poems collection of Tang poetry, xiao occurs in 385 poems, and changxiao in 89. For one example, the famous poet Li Bai (701–762) wrote six poems entitled "Wandering on Mount Tai", the first of which uses changxiao.

Climbing to the heights, I gaze afar at P'eng and Ying; The image imagined—the Terrace of Gold and Silver. At Heaven's Gate, one long whistle I give, And from a myriad li the clear wind comes. Jade maidens, four or five persons, Gliding and whirling descend from the Nine Peripheries. Suppressing smiles, they lead me forward by immaculate hands, And let fall to me a cup of fluid aurora! I bow my head down, salute them twice, Ashamed for myself not to be of a transcendent's caliber.—But broad-ranging enough now to make the cosmos dwindle, I'll leave this world behind, oh how far away![78]

Hushao

The preeminent Chinese avant-garde author Ge Fei wrote the (1995) Hūshào 忽哨 "Whistling" short story, using the modern "whistle" term with shào 哨 instead of xiào 嘯 in Xiaofu, Xiaozhi, etc. The two main characters are based on the historical figures Sun Deng and Ruan Ji who were proficient in transcendental whistling. Victor Mair, who translated "Whistling" into English, says

An old legend of the celebrated encounter between the two men has Ruan Ji visiting Sun Deng in his hermitage but not receiving any responses to his questions. Thereupon, he withdraws and, halfway up a distant mountain, lets out a loud, piercing whistle. This is followed by Sun Deng's magnificent whistled reply, which inspires Ruan Ji to write the "Biography of Master Great Man," an encomium in praise of the Taoist "true man" that also satirizes the conventional Confucian "gentleman".[13]

"Whistling" tells how the famous poet Ruan Ji regularly came to visit the aged hermit Sun Deng on Su Gate Mountain 蘇門山 in present-day Henan, and play games of weiqi go. During one go game, Sun was silently pondering how to move a piece, and Ruan surprised him. "When the whistling sound suddenly arose, Sun Deng was totally unprepared for it. The strange, strident sound, mixed with the sounds of the billowing pines, reverberated through the valleys of Su Gate Mountain for a long while without expiring".[13]

After a final game of go, Ruan took his leave from Sun owing to the "prolonged and profound silence that made him feel bored." Sun watches Ruan's silhouette gradually dissolving into the dark green distance,

When the sound of whistling rose beneath the sunny empyrean, Sun Deng shuddered as though it were a bolt out of the blue. Shielding his eyes from the strong light with one hand, he saw Ruan Ji standing on the peak of Su Gate Mountain beneath a solitary tree. Against a backdrop of white clouds like thick cotton fleece, he stood motionless, seeing to wait for Sun Deng's answer. Sun Deng looked all around him, then quietly inserted his thumb and forefinger in his mouth—the extreme frailness of his body and the looseness of his teeth caused him to be unable to produce any sound. The shrill, desolate, plaintive whistle, accompanied by the soughing of the billowing pines, reverberated for a long time in the mountain valleys. It was like the sad wail of the poet who died long ago, penetrating through the barriers of time, continuing up till today, and sinking into the easily awakened dreams of a living person.[79]

References

- Campany, Robert Ford (2002). To Live As Long As Heaven and Earth: Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents. contribution by Hong Ge. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520230347.

- Chan, Tim Wai-Keung (1996). "Ruan Ji's and Xi Kang's Visits to Two 'Immortals'". Monumenta Serica. 44: 141–165. doi:10.1080/02549948.1996.11731289.

- Doctors, Diviners, and Magicians of Ancient China: Biographies of Frang-shih. Translated by DeWoskin, Kenneth J. Columbia University Press. 1983.

- Edwards, Evangeline D. (1957). "'Principles of Whistling'—嘯旨 Hsiao Chih—Anonymous". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 20 (1): 217–229. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00061796. S2CID 177117179.

- The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. Translated by Hawkes, David. Penguin. 2011 [1985]. ISBN 9780140443752.

- Holzman, Donald (2009). Poetry and Politics: The Life and Works of Juan Chi, A.D. 210-263. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521102568.

- The Book of Odes. Translated by Karlgren, Bernhard. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 1950.

- Glosses on the Book of Odes. Translated by Karlgren, Bernhard. Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 1964. ISBN 9780710101211.

- Kroll, Paul W. (1983). "Verses from on High: The Ascent of T'ai Shan". T'oung Pao. Second Series. E.J. Brill. 69 (4/5): 223–260. doi:10.1163/156853283X00090. JSTOR 4528297.

- The Chinese Classics, Vol. IV - Part I: The first part of the She-king, or the Lessons from the States; the Prolegomena. Translated by Legge, James. Hong Kong / London: Lane, Crawford & Co. / Trübner & Co. 1871. Internet Archive

- The Chinese Classics, Vol. IV - Part II: The second, third and fourth parts of the She-king, or the minor Odes of the Kingdom,the greater Odes of the Kingdom, the sacrificial Odes and Praise-songs. Translated by Legge, James. Hong Kong / London: Lane, Crawford & Co. / Trübner & Co. 1871b. Internet Archive

- Wandering on the Way: Early Taoist Tales and Parables of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Mair, Victor H. Bantam Books. 1994.

- Jing Wang, ed. (1998). "Ge Fei, Whistling". China′s Avant-Garde Fiction: An Anthology. Translated by Mair, Victor H. Duke University Press. pp. 43–68.

- The Huainanzi: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Government in Early Han China. Translated by Major, John S.; Queen, Sarah; Meyer, Andrew; Roth, Harold D. Columbia University Press. 2010. ISBN 9780231142045.

- Mather, Richard B. (1976). Shih-shuo Hsin-yu: A New Account of Tales of the World. University of Minnesota Press.

- Varsano, Paula M. (1999). "Looking for the Recluse and Not Finding Him In: The Rhetoric of Silence in Early Chinese Poetry". Asia Major. 12 (2): 39–70.

- The Book of Songs. Translated by Waley, Arthur. Grove. 1960 [1937].

- Victor H. Mair, ed. (1994). "Ch'eng-Kung Sui Rhapsody on Whistling". The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature. Translated by White, Douglas A. Columbia University Press. pp. 429–434. ISBN 9780231074292.

Footnotes

- ↑ Sacred Books of the East. Volume 28: The Li Ki (Book of Rites), Chs. 11–46. Translated by Legge, James. Oxford University Press. 1885. p. 397.

- ↑ Schuessler, Axel (2007). ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. Honolulu HI: University of Hawai'i Press. p. 422. ISBN 9780824829759.

- ↑ Holzman 2009, p. 151.

- ↑ Giles, Lionel (1948), A Gallery of Chinese Immortals, Selected Biographies Translated from Chinese Sources, John Murray.

- ↑ Kroll 1983.

- 1 2 Egan, Ronald C. (1994), Word, image, and deed in the life of Su Shi, Harvard University Asia Center. p. 248.

- 1 2 Hegel, Robert E. (1998), "The Sights and Sounds of Red Cliffs: On Reading Su Shi", Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews 20: 11-30.

- ↑ Mair, Victor H., ed. (1996). The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231074292.

- ↑ Mair 1998.

- ↑ Minford, John (2014), I Ching: The Essential Translation of the Ancient Chinese Oracle and Book of Wisdom, Viking.

- ↑ Chan 1996.

- ↑ Varsano 1999.

- 1 2 3 Mair 1998, p. 43.

- ↑ DeWoskin 1983, p. 77.

- ↑ Kohn, Livia (2012), A Source Book in Chinese Longevity, Three Pines Press. p.233.

- ↑ Su (2006): 29, 32.

- ↑ Su (2006): 28.

- ↑ Legge 1871.

- ↑ Waley 1937.

- ↑ Karlgren 1950.

- ↑ Legge 1871, p. 33.

- ↑ Waley 1937, p. 74.

- ↑ Karlgren 1950, p. 13.

- ↑ Legge 1871b, p. 417.

- ↑ Waley 1937, p. 103.

- ↑ Karlgren 1950, p. 182.

- ↑ Legge 1871, p. 117.

- ↑ Waley 1937, p. 59.

- ↑ Karlgren 1950, p. 47.

- ↑ Su (2006): 16.

- 1 2 Karlgren 1964, pp. 104–5.

- ↑ Su (2006): 17.

- ↑ Hawkes 2011, p. 105.

- ↑ Hawkes 2011, pp. 219–20.

- ↑ Hawkes 2011, p. 244.

- ↑ Hawkes 2011, p. 257.

- ↑ Hawkes 2011, p. 298.

- ↑ Karlgren 1964, p. 105.

- ↑ Major et al 2010, p. 116.

- ↑ Major et al 2010, p. 227.

- ↑ Tr. Waley, Arthur (1938), The Analects of Confucius, Vintage. p. 219.

- ↑ Mair 1994, pp. 40–1.

- ↑ Su (2006): 41.

- ↑ Su (2006): 37.

- ↑ White 1994, pp. 429–30.

- ↑ Mair 1994, p. 430.

- ↑ White 1994, pp. 430, 432.

- ↑ White 1994, p. 431.

- ↑ White 1994, p. 433.

- ↑ Goodman, Howard L. (2010), Xun Xu and the Politics of Precision in Third-Century AD China, Brill. p. 139.

- 1 2 White 1994, p. 434.

- ↑ Tr. Campany 2002, pp. 240–2.

- ↑ Tr. Campany 2002, p. 249.

- ↑ Tr. Campany 2002, pp. 322–3, cf. DeWoskin 1983, pp. 82–3.

- ↑ Tr. Mather 1976, p. 331.

- 1 2 Holzman 2009, p. 152.

- ↑ Tr. Mather 1976, pp. 331–2.

- ↑ Tr. Mather 1976, p. 332.

- ↑ Tr. Varsano 1999, p. 56.

- ↑ Varsano 1999, p. 57.

- ↑ Tr. Holzman 2009, pp. 149–50.

- ↑ Chan 1996, pp. 151, 158.

- ↑ Tr. Watt James C. Y. and Prudence Oliver Harper, eds. (2004), China: Dawn Of A Golden Age, 200-750 AD, Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 8.

- ↑ Edwards 1957, p. 218.

- 1 2 Kroll 1983, p. 250.

- ↑ Edwards 1957, p. 217.

- ↑ Tr. Edwards 1957, pp. 218–9.

- ↑ Adapted from Edwards 1957, pp. 219–20.

- ↑ Birrell, Anne, tr. (2000), The Classic of Mountains and Seas, Penguin. p. 24.

- ↑ Su (2006): 19.

- ↑ Tr. Edwards 1957, pp. 220–1.

- ↑ Tr. Edwards 1957, p. 226.

- ↑ Tr. Edwards 1957, pp. 222–3.

- ↑ Tr. Edwards 1957, p. 227.

- ↑ Tr. Edwards 1957, p. 228.

- ↑ Tr. Edwards 1957, p. 228.

- ↑ Su (2006): 43.

- ↑ Tr. Kroll 1983, p. 249.

- ↑ Mair 1998, p. 68.

External links

- White, Douglas A. (1964, 2009), Ch’eng-kung Sui’s (成公綏) Poetic Essay on Whistling (The Hsiao Fu 嘯賦), Harvard University.

- 嘯賦, Xiaofu, Wikisource edition, (in Chinese)

- 嘯旨, Xiaozhi, Wikisource edition, (in Chinese)