.svg.png.webp) | |

| Abbreviation | TfL |

|---|---|

| Formation | 3 July 2000 (Greater London Authority Act 1999) |

| Type | Statutory corporation |

| Legal status | Executive agency within GLA |

| Purpose | Transport authority |

| Headquarters | 5 Endeavour Square London E20 1JN |

Region served | London, England |

Chairman | Mayor of London (Sadiq Khan) |

| Andy Lord | |

Main organ | |

Parent organisation | Greater London Authority (GLA) |

Budget | 2019–20: £10.3 billion (47% of this from fares)[1] |

Staff | 28,000 |

| Website | tfl |

| This article is part of a series within the Politics of England on the |

| Politics of London |

|---|

|

Transport for London (TfL) is a local government body responsible for most of the transport network in London, United Kingdom.[2]

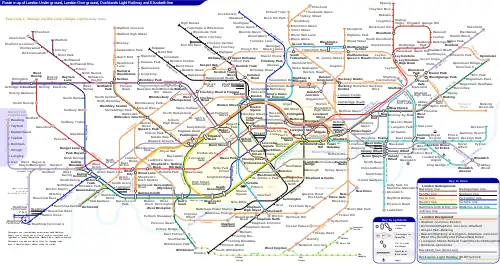

TfL has responsibility for multiple rail networks including the London Underground and Docklands Light Railway, as well as London's buses, taxis, principal road routes, cycling provision, trams, and river services. It does not control all National Rail services in London, although it is responsible for London Overground and Elizabeth line services. The underlying services are provided by a mixture of wholly owned subsidiary companies (principally London Underground), by private sector franchisees (the remaining rail services, trams and most buses) and by licensees (some buses, taxis and river services). TfL was also responsible, jointly with the national Department for Transport (DfT), for commissioning the construction of the new Crossrail Project and is now responsible for franchising its operation as the Elizabeth line.[3]

In 2019–20, TfL had a budget of £10.3 billion, 47% of which came from fares. The rest came from grants, mainly from the Greater London Authority (33%), borrowing (8%), congestion charging and other income (12%). Direct central government funding for operations ceased in 2018.[1] In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom, TfL sought urgent government support as fare revenues dropped 90%, and proposed near 40% cuts in capital expenditure.

History

TfL was created in 2000 as part of the Greater London Authority (GLA) by the Greater London Authority Act 1999.[4] It gained most of its functions from its predecessor London Regional Transport in 2000. The first Commissioner of TfL was Bob Kiley. The first chair was then-Mayor of London Ken Livingstone, and the first deputy chair was Dave Wetzel. Livingstone and Wetzel remained in office until the election of Boris Johnson as Mayor in 2008. Johnson took over as chairman, and in February 2009 fellow-Conservative Daniel Moylan was appointed as his deputy.

TfL did not take over responsibility for the London Underground until 2003, after the controversial public-private partnership (PPP) contract for maintenance had been agreed. Management of the Public Carriage Office had previously been a function of the Metropolitan Police.

Transport for London Corporate Archives holds business records for TfL and its predecessor bodies and transport companies. Some early records are also held on behalf of TfL Corporate Archives at the London Metropolitan Archives.

After the bombings on the underground and bus systems on 7 July 2005, many staff were recognised in the 2006 New Year honours list for the work they did. They helped survivors out, removed bodies, and got the transport system up and running, to get the millions of commuters back out of London at the end of the workday.[lower-alpha 1]

On 1 June 2008, the drinking of alcoholic beverages was banned on Tube and London Overground trains, buses, trams, Docklands Light Railway and all stations operated by TfL across London but not those operated by other rail companies.[8][9] Carrying open containers of alcohol was also banned on public transport operated by TfL. The then-Mayor of London Boris Johnson and TfL announced the ban with the intention of providing a safer and more pleasant experience for passengers. There were "Last Round on the Underground" parties on the night before the ban came into force. Passengers refusing to observe the ban may be refused travel and asked to leave the premises. The GLA reported in 2011 that assaults on London Underground staff had fallen by 15% since the introduction of the ban.[10]

TfL commissioned a survey in 2013 which showed that 15% of women using public transport in London had been the subject of some form of unwanted sexual behaviour but that 90% of incidents were not reported to the police. In an effort to reduce sexual offences and increase reporting, TfL—in conjunction with the British Transport Police, Metropolitan Police Service, and City of London Police—launched Project Guardian.[11]

In 2014, Transport for London launched the 100 years of women in transport campaign in partnership with the Department for Transport, Crossrail,[12] Network Rail,[13] the Women's Engineering Society[14] and the Women's Transportation Seminar (WTS). The programme was a celebration of the significant role that women had played in transport over the previous 100 years, following the centennial anniversary of the First World War, when 100,000 women entered the transport industry to take on the responsibilities held by men who enlisted for military service.[15]

COVID-19 pandemic impacts

In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom, TfL services were reduced. All Night Overground and Night Tube services, as well as all services on the Waterloo & City line, were suspended from 20 March, and 40 tube stations were closed on the same day.[16] The Mayor of London and TfL urged people to only use public transport if absolutely essential, so that it could be used by critical workers.[17] The London Underground brought in new measures on 25 March to combat the spread of the virus, by slowing the flow of passengers onto platforms. Measures included the imposition of queuing at ticket gates and turning off some escalators.[18] In April, TfL trialled changes encouraging passengers to board London buses by the middle doors to lessen the risks to drivers, after the deaths of 14 TfL workers including nine drivers.[19] This measure was extended to all routes on 20 April, and passengers were no longer required to pay, so that they did not need to use the card reader near the driver.[20]

On 22 April, London mayor Sadiq Khan warned that TfL could run out of money to pay staff by the end of April unless the government stepped in.[21] Two days later, TfL announced it was furloughing around 7,000 employees, about a quarter of its staff, to help mitigate a 90% reduction in fare revenues. Since London entered lockdown on 23 March, Tube journeys had fallen by 95% and bus journeys by 85%, though TfL continued to operate limited services to allow "essential travel" for key workers.[22] Without government financial support for TfL, London Assembly members warned that Crossrail, the Northern line extension and other projects such as step-free schemes at tube stations could be delayed.[23]

On 7 May, it was reported that TfL had requested £2 billion in state aid to keep services running until September 2020.[24] On 12 May, TfL documents warned it expected to lose £4bn due to the pandemic and said it needed £3.2bn to balance a proposed emergency budget for 2021, having lost 90% of its overall income. Without an agreement with the government, deputy mayor for transport Heidi Alexander said TfL might have to issue a Section 114 notice - the equivalent of a public body going bust.[25] On 14 May, the UK Government agreed £1.6bn in emergency funding to keep Tube and bus services running until September[26] - a bailout condemned as "a sticking plaster" by Khan who called for agreement on a new longer-term funding model.[27]

On 1 June 2020, TfL released details of its emergency budget for 2020–2021, revealing it planned to reduce capital investment by 39% from £1.3bn to £808m, and to cut maintenance and renewal spending by 38% to £201m.[28]

Organisation

TfL is controlled by a board whose members are appointed by the Mayor of London,[29] a position held by Sadiq Khan since May 2016. The Commissioner of Transport for London reports to the Board and leads a management team with individual functional responsibilities.

The body is organised in two main directorates and corporate services, each with responsibility for different aspects and modes of transport. The two main directorates are:

- London Underground, responsible for running London's underground rail network, commonly known as the tube, and managing the provision of maintenance services by the private sector. This network is sub-divided into different service delivery units:

- London Underground

- Deep Tube: Bakerloo, Central, Victoria, Waterloo & City, Jubilee, Northern and Piccadilly lines.

- SSL (Sub Surface Lines): Metropolitan, District, Circle and Hammersmith & City lines.

- Elizabeth line, a high-frequency hybrid urban–suburban rail service on dedicated infrastructure in central London (built as part of the Crossrail Project); and on National Rail lines to the east and west of the city. Operation is undertaken by MTR Elizabeth line, a private-sector concessionaire, and maintenance by Network Rail.

- London Underground

- Surface Transport, consisting of:

- Docklands Light Railway (DLR): an automatically driven light metro network in East and South London, although actual operation and maintenance is undertaken by a private-sector concessionaire (a joint venture of Keolis and Amey).

- London Buses, responsible for managing the red bus network throughout London and branded services including East London Transit, largely by contracting services to various private sector bus operators. Incorporating CentreComm, London Buses Command & Control Centre, a 24-hour Emergency Control Centre based in Southwark.

- London Dial-a-Ride, which provides community transport services throughout London.

- London Overground, which consists of certain suburban National Rail services within London. Operation is undertaken by Arriva Rail London, a private-sector concessionaire, and maintenance by Network Rail.

- London River Services, responsible for licensing and co-ordinating passenger services on the River Thames within London.

- London Streets, responsible for the management of London's strategic road network.

- London Trams, responsible for managing London's tram network, by contracting to private sector operators. At present the only tram system is Tramlink in South London, contracted to FirstGroup, but others are proposed.

- London congestion charge, a fee charged on most cars and motor vehicles being driven within the Congestion Charge Zone in Central London.

- Public Carriage Office, responsible for licensing the famous black cab taxis and private hire vehicles.

- Victoria Coach Station, which owns and operates London's principal terminal for long-distance bus and coach services.

- "Delivery Planning" which promotes cycling in London, including the construction of Cycle Superhighways.

- "Special Projects Team" manages the contract with Serco for the Santander Cycles bike rental scheme.

- Walking, which promotes better pedestrian access and better access for walking in London.

- London Road Safety Unit, which promotes safer roads through advertising and road safety measure.

- Community Safety, Enforcement and Policing, responsible for tackling fare evasion on buses, delivering policing services that tackle crime and disorder on public transport in co-operation with the Metropolitan Police Service's Transport Operational Command Unit (TOCU) and the British Transport Police.

- Traffic Enforcement, responsible for enforcing traffic and parking regulations on the red routes.

- Freight Unit, which has developed the "London Freight Plan"[30] and is involved with setting up and supporting a number of Freight Quality Partnerships covering key areas of London.

Operations centre

TfL's Surface Transport and Traffic Operations Centre (STTOC) was officially opened by Prince Andrew, Duke of York, in November 2009.[31][32] The centre monitors and coordinates official responses to traffic congestion, incidents and major events in London.[33] London Buses Command and Control Centre (CentreComm), London Streets Traffic Control Centre (LSTCC) and the Metropolitan Police Traffic Operation Control Centre (MetroComm) were brought together under STTOC.[33]

STTOC played an important part in the security and smooth running of the 2012 Summer Olympics.[33] The London Underground Network Operations Centre is now located on the fifth floor of Palestra and not within STTOC.[34][35] The centre featured in the 2013 BBC Two documentary series The Route Masters: Running London's Roads.

Connect project

Transport for London introduced the "Connect" project for radio communications during the 2000s, to improve radio connections for London Underground staff and the emergency services.[36][37] The system replaced various separate radio systems for each tube line, and was funded under a private finance initiative. The supply contract was signed in November 1999 with Motorola as the radio provider alongside Thales. Citylink's shareholders are Thales Group (33 per cent), Fluor Corporation (18%), Motorola (10%), Laing Investment (19.5%) and HSBC (19.5%). The cost of the design, build and maintain contract was £2 billion over twenty years. Various subcontractors were used for the installation work, including Brookvex and Fentons.

A key reasoning for the introduction of the system was in light of the King's Cross fire disaster, where efforts by the emergency services were hampered by a lack of radio coverage below ground. Work was due to be completed by the end of 2002, although suffered delays due to the necessity of installing the required equipment on an ageing railway infrastructure with no disruption to the operational railway. On 5 June 2006 the London Assembly published the 7 July Review Committee report, which urged TfL to speed up implementation of the Connect system.[36]

The East London line was chosen as the first line to receive the TETRA radio in February 2006, as it was the second smallest line and is a mix of surface and sub surface. In the same year it was rolled out to the District, Circle, Hammersmith & City, Metropolitan and Victoria lines, with the Bakerloo, Piccadilly, Jubilee, Waterloo & City and Central lines following in 2007.[38] The final line, the Northern, was handed over in November 2008.

The 2010 TfL investment programme included the project "LU-PJ231 LU-managed Connect communications", which provided Connect with a new transmission and radio system comprising 290 cell sites with two to three base stations, 1,400 new train mobiles, 7,500 new telephone links and 180 CCTV links.[37]

London Transport Museum

TfL also owns and operates the London Transport Museum in Covent Garden, a museum that conserves, explores and explains London's transport system heritage over the last 200 years. It both explores the past, with a retrospective look at past days since 1800, and the present-day transport developments and upgrades. The museum also has an extensive depot, situated at Acton, that contains material impossible to display at the central London museum, including many additional road vehicles, trains, collections of signs and advertising materials. The depot has several open weekends each year. There are also occasional heritage train runs on the Metropolitan line.

Fares

Most of the transport modes that come under the control of TfL have their own charging and ticketing regimes for single fare. Buses and trams share a common fare and ticketing regime, and the DLR, Overground, Underground, and National Rail services another.

Zonal fare system

Rail service fares in the capital are calculated by a zonal fare system. London is divided into eleven fare zones, with every station on the London Underground, London Overground, Docklands Light Railway and, since 2007, on National Rail services, being in one, or in some cases, two zones. The zones are mostly concentric rings of increasing size emanating from the centre of London. They are (in order):

Travelcard

Superimposed on these mode-specific regimes is the Travelcard system, which provides zonal tickets with validities from one day to one year, and off-peak variants. These are accepted on the DLR, buses, railways, trams, and the Underground, and provide a discount on many river services fares.

Oyster card

The Oyster card is a contactless smart card system introduced for the public in 2003, which can be used to pay individual fares (pay as you go) or to carry various Travelcards and other passes. It is used by scanning the card at a yellow card reader. Such readers are found on ticket gates where otherwise a paper ticket could be fed through, allowing the gate to open and the passenger to walk through, and on stand-alone Oyster validators, which do not operate a barrier. Since 2010, Oyster Pay as you go has been available on all National Rail services within London. Oyster Pay as you go has a set of daily maximum charges that are the same as buying the nearest equivalent Day Travelcard.

Contactless payments

Almost all contactless Visa, Maestro, MasterCard and American Express debit and credit cards issued in the UK, and also most international cards supporting contactless payment, are accepted for travel on London Underground, London Overground, Docklands Light Railway, most National Rail, London Tramlink and Bus services. This works in the same way for the passenger as an Oyster card, including the use of capping and reduced fares compared to paper tickets. The widespread use of contactless payment - around 25 million journeys each week[39][40] - has meant that TfL is now one of Europe's largest contactless merchants, with one in 10 contactless transactions in the UK taking place on the TfL network.[41][42]

Mobile payments - such as Apple Pay, Google Pay and Samsung Pay - are also accepted in the same way as contactless payment cards. The fares are the same as those charged on a debit or credit card, including the same daily capping.[43] In 2020, one in five journeys are made using mobile devices instead of using contactless bank cards,[40] and TfL had become the most popular Apple Pay merchant in the UK.[44][45][46]

TfL's expertise in contactless payments has led other cities such as New York, Sydney, Brisbane and Boston to license the technology from TfL and Cubic.[41][47]

Identity and marketing

Each of the main transport units has its own corporate identity, formed by differently coloured versions of the standard roundel logo and adding appropriate lettering across the horizontal bar. The roundel rendered in blue without any lettering represents TfL as a whole (see Transport for London logo), as well as used in situations where lettering on the roundel is not possible (such as bus receipts, where a logo is a blank roundel with the name "London Buses" to the right). The same range of colours is also used extensively in publicity and on the TfL website.

Transport for London has always mounted advertising campaigns to encourage use of the Underground. For example, in 1999, they commissioned artist Stephen Whatley to paint an interior – 'The Grand Staircase' – which he did on location inside Buckingham Palace. This painting was reproduced on posters and displayed all over the London Underground.[48]

In 2010 they commissioned artist Mark Wallinger to assist them in celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Underground, by creating the Labyrinth Project, with one enamel plaque mounted permanently in each of the Tube's 270 stations.[49]

In 2015, in partnership with the London Transport Museum and sponsored by Exterion Media,[50] TfL launched Transported by Design,[51] an 18-month programme of activities. The intention is to showcase the importance of both physical and service design across London's transport network. In October 2015, after two months of public voting, the black cab topped the list of favourite London transport icons, which also included the original Routemaster bus and the Tube map, among others.[52] In 2016, the programme held exhibitions,[53] walks[54] and a festival at Regent Street on 3 July.[55][56]

Typeface

Johnston (or Johnston Sans) is typeface designed by and named after Edward Johnston. The typeface was commissioned in 1913 by Frank Pick, then commercial manager of the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (also known as 'The Underground Group'), as part of his plan to strengthen the company's corporate identity.[57] Johnston was originally created for printing (with a planned height of 1 inch or 2.5 cm), but it rapidly became used for the enamel station signs of the Underground system as well.[58]

Johnston was originally printed using wood type for large signs and metal type for print. Johnston was redesigned in 1979 to produce New Johnston. The new family comes in eight members: Light, Medium, Bold weights with corresponding Italics, Medium Condensed and Bold Condensed. After the typeface was digitized in 1981–82, New Johnston finally became ready for Linotron photo-typesetting machine, and first appeared in London's Underground stations in 1983. It has been the official typeface exclusively used by Transport for London and The Mayor of London ever since, with minor updates to specific letterforms occurring in 1990–1992 and 2008. A new version, known as Johnston 100, was commissioned by Transport for London from Monotype in 2016 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the introduction of the typeface, and was designed to be closer to the original version of the Johnston typeface.[59][60][61]

Advertising bans

In May 2019, TfL banned advertising from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates due to their poor human rights records. This brought the number of countries to 11 from which TfL has banned adverts, due to them having the death penalty for homosexuals. Countries previously banned from advertising were Iran, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen.[62]

In 2019, the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, introduced restrictions on advertising of unhealthy food and drinks across the TfL network. A study estimated that this led to a 7% reduction in the average weekly household purchase of foods high in fat, salt, and sugar. The largest reductions were seen in the sales of chocolate and sweets. There was no change in purchases of foods not classified as being high in fat, salt, and sugar.[63][64]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Those mentioned include Peter Hendy, who was at the time Head of Surface Transport division, and Tim O'Toole, head of the Underground division, who were both awarded CBEs.[5][6][7] Others included David Boyce, Station Supervisor, London Underground (MBE);[5] John Boyle, Train Operator, London Underground (MBE);[5] Peter Sanders, Group Station Manager, London Underground (MBE);[5] Alan Dell, Network Liaison Manager, London Buses (MBE)[5] and John Gardner, Events Planning Manager (MBE).[7]

References

- 1 2 "TfL funding". Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ "Company information". Transport for London. 2019. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- ↑ "Our role". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

- ↑ "Legislative framework". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alan Hamilton (16 February 2006). "It was all just part of the job, say honoured 7/7 heroes". The Times. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ "Queen hails brave 7 July workers". BBC News. 15 February 2006. Archived from the original on 5 June 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- 1 2 "Two TfL July 7 heroes honoured in New Years List". Transport for London. 2 January 2007. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ "Revellers' farewell to Tube alcohol". Metro. 1 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Johnson bans drink on transport". BBC News. 7 May 2008. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- ↑ "Londoners continue to back Mayor's booze ban". Greater London Authority. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ Bates, Laura (1 October 2013). "Project Guardian: making public transport safer for women". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ "Crossrail partners with Women into Construction". Archived from the original on 28 September 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ "In Your Area". Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ "100 Years of Women in Transport – Women's Engineering Society". Archived from the original on 14 May 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ "The first 100 years of women in transport". Archived from the original on 2 October 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: London cuts Tube trains and warns 'don't travel unless you really have to'". Sky News. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ "Planned services to support London's critical workers". Transport for London. 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 20 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ↑ "New Tube restrictions to stop non-essential trips". BBC News. 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2020. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ↑ Champion, Ben (9 April 2020). "Coronavirus: London to trial new way of using buses after 14 transport workers die from Covid-19". Independent. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Free travel and middle door only boarding on London buses". Sky News. 17 April 2020. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: London transport 'may run out of money by end of month'". BBC News. 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Transport for London furloughs 7,000 staff". BBC News. 24 April 2020. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- ↑ Kelly, Megan (28 April 2020). "Fears for London projects as TfL seeks support". Construction News. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ↑ McDonald, Henry (7 May 2020). "London needs £2bn to keep transport system running until autumn". Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Transport for London expects to lose £4bn". BBC News. 13 May 2020. Archived from the original on 25 June 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ↑ "Coronavirus: Transport for London secures emergency £1.6bn bailout". BBC News. 14 May 2020. Archived from the original on 13 July 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ↑ O'Connor, Rob (18 May 2020). "London mayor describes TfL's £1.6bn bailout as "sticking plaster"". Infrastructure Intelligence. Archived from the original on 1 June 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ↑ Garner-Purkis, Zak (1 June 2020). "TfL to slash spending by £525m". Construction News. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- ↑ "Board members". Transport for London. 2013. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ↑ "Freight". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

- ↑ "HRH The Duke of York opens state of the art transport control centre". Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ "Duke of York opens TfL control centre at Palestra in Blackfriars Road". Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Evidence for Transport Committee's investigation into 2012 transport" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ "Transport for London Board Agenda Item 5, 2 November 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- ↑ "Southwark chosen for LUL command and control centre". Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- 1 2 "TfL keeps schtum on underground radio plans". The Register. 6 June 2006. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- 1 2 "TfL investment programme – London Underground" (PDF). Transport for London. 2010. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ↑ "Response from the Chief Engineers' Directorate of London Underground to the OFCOM Consultative Document "Spectrum Trading Consultation"" (PDF). Ofcom. November 2003. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ↑ "Contactless payments are taking over the tube network". Evening Standard. 24 April 2018. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Apple Pay upgrade to make TfL contactless payments easier". CityAM. 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Licencing London's contactless ticketing system". Transport for London. 13 July 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ "Contactless and mobile pay as you go". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ↑ "Contactless and mobile pay as you go". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ↑ Mortimer, Natalie (20 July 2015). "TfL proves most popular retailer on Apple Pay UK following launch". The Drum. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Titcomb, James (20 July 2015). "How London's transport crunch forged a contactless revolution". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ Gibbs, Samuel (16 July 2015). "TfL cautions users over pitfalls of Apple Pay". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ↑ "Deal worth up to £15m is a first for TfL and allows other cities around the world to benefit from London's contactless ticketing technology". www.cubic.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ↑ "Artist: Stephen B Whatley – Poster and poster artwork collection". London Transport Museum. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ↑ Mark Brown (7 February 2013). "Tube celebrates 150th birthday with labyrinth art project". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ "Exterion Media sponsors TfL". 17 September 2015. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Transport for London. "Transported by Design". Archived from the original on 17 April 2016.

- ↑ "Vote Now For London's Best Transport Design Icon". 2 September 2015. Archived from the original on 27 September 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ "London Transport Museum Opens New 'London By Design' Gallery". 1 November 2015. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ "Winter Wanders". 6 January 2016. Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ "TfL announces plans for Regent Street design festival". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ "2016 on Regent Street". Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Green, Oliver; Rewse-Davies, Jeremy (1995). Designed for London: 150 years of transport design. London: Laurence King. pp. 81–2. ISBN 1-85669-064-4.

- ↑ Howes, Justin (2000). Johnston's Underground Type. Harrow Weald, Middlesex: Capital Transport. pp. 36–44. ISBN 1-85414-231-3.

- ↑ Howes, Justin (2000). Johnston's Underground Type. Harrow Weald, Middlesex: Capital Transport. pp. 73–78. ISBN 1-85414-231-3.

- ↑ "Introducing Johnston100, the language of London". 2017. Archived from the original on 23 April 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ↑ "A century of type". Transport for London. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ↑ "Transport for London suspends adverts from Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and the United Arab Emirates due to poor human rights". Attitude.co.uk. 2 May 2019. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ↑ "Advertising ban was linked to lower purchases of unhealthy food and drink". NIHR Evidence. 3 August 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_52264. S2CID 251337598. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ Yau, Amy; Berger, Nicolas; Law, Cherry; Cornelsen, Laura; Greener, Robert; Adams, Jean; Boyland, Emma J.; Burgoine, Thomas; de Vocht, Frank; Egan, Matt; Er, Vanessa; Lake, Amelia A.; Lock, Karen; Mytton, Oliver; Petticrew, Mark (17 February 2022). Popkin, Barry M. (ed.). "Changes in household food and drink purchases following restrictions on the advertisement of high fat, salt, and sugar products across the Transport for London network: A controlled interrupted time series analysis". PLOS Medicine. 19 (2): e1003915. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003915. ISSN 1549-1676. PMC 8853584. PMID 35176022.