女性歇斯底里

女性歇斯底里、女性歇斯底里症、雌性歇斯底里、雌性歇斯底里症(英語:)曾是女性常見的醫學診斷,表現的症狀包括焦慮、呼吸急促、昏厥、緊張、对食物或性生活失去胃口,性慾、失眠、腹重、煩躁以及「為他人製造麻煩的傾向」。[1]医学界已不再承认它是一种医学疾病。它的诊断和治疗在西欧已经有数百年的历史。[1]

| Female hysteria 雌性歇斯底里 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 催眠影響下歇斯底里的女性 | |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 醫學專科 | Psychiatry |

早期歷史

歇斯底里的歷史可以追溯到遠古時代。追溯到公元前1900年古埃及,在Medizinische Papyri aus Lahun發現了對女性歇斯底里的第一次描述。[4]

In this culture, the womb was thought capable of affecting much of the rest of the body, but "there is no warrant for the fanciful view that the ancient Egyptians believed that a variety of bodily complaints were due to an animate, wandering womb".[5] 子宫脱垂 was also known.

In 古希腊, wandering womb was described in the gynecological treatise of the Hippocratic Corpus, "Diseases of Women",[6] which dates back to the 5th and 4th centuries BC. 柏拉图's dialogue Timaeus compares a woman's 子宫 to a living creature that wanders throughout a woman's body, "blocking passages, obstructing breathing, and causing disease".[7] 阿莱泰乌斯 described the uterus as "an animal within an animal" (less emotively, "a living thing inside a living thing"), which causes symptoms by wandering around a woman's body putting pressure on other organs.[6] Timaeus also argued that the uterus is "sad and unfortunate" when it does not join with a male or bear child.[4] The standard cure for this "hysterical suffocation" was scent therapy, in which good smells were placed under a woman's genitals and bad odors at the nose, while sneezing could be also induced to drive the uterus back to its correct place.[6] The concept of a pathological "wandering womb" was later viewed as the source of the term hysteria,[7] which stems from the Greek cognate of uterus, ὑστέρα (hystera), although the word hysteria does not feature in ancient Greek medicine: 'the noun is not used in this period'.[7]

While in the Hippocratic texts a wide range of women were susceptible – including in particular the childless – 盖伦 in the 2nd century omitted the childless and saw the most vulnerable group as "widows, and particularly those who previously menstruated regularly, had been pregnant and were eager to have intercourse, but were now deprived of all this" (On the Affected Parts, 6.5).[6] He also denied that the womb could "move from one place to another like a wandering animal".[6] His treatments included scent therapy and sexual intercourse, but also rubbing in ointments to the external genitalia; this was to be performed by midwives, not physicians.[6]

While most Hippocratic writers saw the retention of menstrual blood in the womb as a key problem, for Galen even more serious was the retention of "female seed".[8] This was believed to be thinner than male seed and could be retained in the womb.[7] Hysteria was referred to as "the widow's disease", because the female semen was believed to turn venomous if not released through regular climax or intercourse.[9] If the patient was married, this could be completed by intercourse with their spouse. Other than participating in sexual intercourse, it was thought that fumigating the body with special fragrances would supposedly draw the uterus back to its natural spot in the female body. Foul smells applied to the nose would drive it down, and pleasant scents at the vulva would attract it.[7]

中世紀近代

Through the Middle Ages, another cause of dramatic symptoms could be found: demonic possession.[10] It was thought that demoniacal forces were attracted to those who were prone to melancholy, particularly to single women and the elderly. When a patient could not be diagnosed or cured of a disease, it was thought that the symptoms of what would now be diagnosed as mental illness, were actually those of someone possessed by the devil.[4] After the 17th century, the correlation of demonic possession and hysteria were gradually discarded and instead was described as behavioral deviance, a medical issue.[11]

In the 16th and 17th centuries, hysteria was still believed to be due to the retention of humour or fluids in the uterus, sexual deprivation, or by the tendency of the uterus to wander around the female body causing irritability and suffocation. Self-treatment such as 自慰, was not recommended and was also considered taboo. Marriage, and regular sexual encounters with her husband, was still the most highly recommended long-term course of treatment for a woman with hysteria.[4][12] It was thought to purge the uterus of any built-up fluid, and semen was thought to have healing properties, In this model, ejaculation outside the vagina was conducive to uterine disease since the female genitalia did not receive the health benefits of male emission. Some physicians regarded all contraceptive practices as injurious to women for this reason. Giovanni Matteo Ferrari da Gradi cited marriage and childbearing as a cure for the disease. If pleasure was obtained from them, then hysteria could be cured.[12] If a woman was unmarried, or widowed, manual stimulation by a midwife involving certain oils and scents was recommended to purge the uterus of any fluid retention. Lack of marriage was also thought to be the cause of most melancholy in single women, such as nuns or widows. Studies of the causes and effects of hysteria were continued in the 16th and 17th century by medical professionals such as 安布鲁瓦兹·帕雷, Thomas Sydenham, and Abraham Zacuto, who published their findings furthering medical knowledge of the disease, and informing treatment.[12][4] Physician Abraham Zacuto writes in his Praxis Medica Admiranda from 1637,

'Because of retention of the sexual fluid, the heart and surrounding areas are enveloped in a morbid and moist exudation: this is especially true of the more lascivious females, inclined to venery, passionate women who are most eager to experience physical pleasure; if she is of this type she cannot ever be relieved by any aid except that of her parents who are advised to find her a husband. Having done so the man's strong and vigorous intercourse alleviated the frenzy.'

——Maines, 29,[12]

There was continued debate about whether it was morally acceptable for a physician to remove excess female seed through genital manipulation of the female patient; Pieter van Foreest (Forestus) and Giovanni Matteo da Grado (Gradus) insisted on using midwives as intermediaries, and regarded the treatment as the last resort.[13]

1700

In the 18th century, hysteria slowly became associated with mechanisms in the brain rather than the uterus. This is also when it was noted both men and women could contract hysteria.[14] French physician 菲利普·皮內爾 freed hysteria patients detained in Paris' Salpêtrière 療養院 on the basis that kindness and sensitivity were needed to formulate good care. Another French physician, Francois de Sauvages de La Croix believed some common signs of female hysteria were "tears and laughter, oscitation [yawning], pandiculation (stretching and yawning), suffocating angina (chest pain) or dyspnea (shortness of breath), dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), delirium, a close and driving pulse, a swollen abdomen, cold extremities, and abundant and clear urine."[14]

1800

让-马丁·沙可 argued that hysteria derived from a neurological disorder and showed that it was more common in men than women.[4] Charcot's theories of hysteria being a physical condition of the mind and not of the body led to a more scientific and analytical approach to hysteria in the 19th century. He dispelled the beliefs that hysteria had anything to do with the supernatural and attempted to define it medically.[15] Charcot's use of photography,[16] and the resulting concretization of women's expressions of health and distress, continued to influence women's experiences of seeking healthcare.[17] Though older ideas persisted during this era, over time female hysteria began to be thought of less as a physical ailment and more of a psychological one.[18]

George Beard, a physician who cataloged an incomplete list including 75 pages of possible symptoms of hysteria,[19] claimed that almost any ailment could fit the diagnosis. Physicians thought that the stress associated with the typical female life at the time caused civilized women to be both more susceptible to nervous disorders and to develop faulty reproductive tracts.[20] One American physician expressed pleasure in the fact that the country was "catching up" to Europe in the prevalence of hysteria.[19]

According to Pierre Roussel and 让-雅克·卢梭, femininity was a natural and essential desire for women: "Femininity is for both authors an essential nature, with defined functions, and the disease is explained by the non-fulfillment of natural desire."[4] It was during the industrial revolution and the major development of cities and modern lifestyles that disruption of this natural appetite was thought to cause lethargy or melancholy, leading to hysteria.[4] At the time female patients sought medical practitioners for the massage treatment of hysteria. The rate of hysteria was so great in the socially restrictive industrial period that women were prone to carry smelling salts about their person in case they swooned, reminiscent of 希波克拉底' theory of using odors to coerce the uterus back into place. For physicians, manual massage treatment was becoming laborious and time-consuming, and they were seeking a way to increase productivity.[12]

Rachel Maines hypothesized that physicians from the classical era until the early 20th century commonly treated hysteria by manually stimulating the genitals of, i. e. masturbating, female patients to the point of 性高潮, which was denominated "hysterical paroxysm", and that the inconvenience of this may have motivated the original development of and market for the vibrator.[1] Other hysteria treatments included pregnancy, marriage, heterosexual sex, and the application of smelling oils on female genitals.[21] Although Maines's theory that hysteria was treated by masturbating female patients to orgasm is widely repeated in the literature on female anatomy and sexuality,[22] some historians dispute Maines's claims regarding the prevalence of this treatment for hysteria and its relevance to the invention of the vibrator, describing them as a distortion of the evidence or that they are only relevant to a very small group.[23][24][25] In 2018, Hallie Lieberman and Eric Schatzberg of 佐治亚理工学院 challenged Maines's claims for the use of electromechanical vibrators to treat hysteria in the 19th century.[26] Maines stated that her theory of the prevalence of masturbation for hysteria and its relevance to the invention of the vibrator is a 假说 and not proven fact.[22]

Frederick Hollick was a firm believer that a main cause of hysteria was licentiousness present in women.[27]

Freud and decline of diagnosis

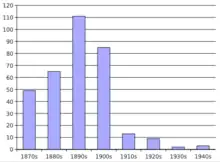

During the early 20th century, the number of women diagnosed with female hysteria sharply declined. This decline has been attributed to many factors. Some medical authors claim that the decline was due to gaining a greater understanding of the psychology behind 转换障碍s such as hysteria.[28]

With so many possible symptoms, historically hysteria was considered a catchall diagnosis where any unidentifiable ailment could be assigned.[4] As diagnostic techniques improved, the number of ambiguous cases that might have been attributed to hysteria declined. For instance, before the introduction of 腦電圖, 癫痫 was frequently confused with hysteria.[29]

西格蒙德·弗洛伊德 claimed that hysteria was not anything physical at all but an emotional, internal condition that could affect both males and females, which was caused by previous trauma that led to the affected being unable to enjoy sex in the normal way.[12][15] This would later lead to Freud's development of the 恋母情结, which connotes femininity as a failure, or lack of masculinity.[15] Although these earlier studies had shown that men were also prone to have hysteria, including Freud himself,[6] over time, the condition was related mainly to issues of femininity as the continued study of hysteria took place only in women.[30] Many cases that had previously been labeled hysteria were reclassified by Freud as 焦慮 neuroses.[29] Sigmund Freud was fascinated by cases of hysteria. He thought that hysteria may have been related to the unconscious mind and separate from the conscious mind or the ego.[31] He was convinced that deep conflicts in the mind, some concerning instinctual drives for sex and aggression, were driving the behavior of those with hysteria. Freud developed 精神分析学 in order to help patients that had been diagnosed with hysteria reduce internal conflicts causing physical and emotional suffering. While hysteria was reframed with reference to new laws and was new in principle, its recommended treatment in psychoanalysis would remain what Bernheimer observes it had been for centuries: marrying and having babies and in this way regaining the "lost" phallus.[15]

New theories relating to hysteria came from pure speculation; doctors and physicians could not connect symptoms to the disorder, causing it to decline rapidly as a diagnosis.[28]

Today, female hysteria is no longer a recognized illness, but different manifestations of hysteria are recognized in other conditions such as 精神分裂症, 边缘型人格障碍, 转换障碍, and anxiety attacks.[32]

與婦女權利和女權主義的關係

The most vehement negative statements associating feminism with hysteria came during the militant suffrage campaign. The American Psychiatric Association did not drop the term "hysteria" until the 1950s.[33] By the 1980s, feminists began to reclaim hysteria, using it as a symbol of the systematic oppression of women and reclaiming the term for themselves.[6] Especially among sex-positive feminists, who believe sexual repression and having it called hysteria is a form of oppression.[6] The idea stemmed from the belief that Hysteria was a kind of pre-feminist rebellion against the oppressive defined social roles placed upon women. Feminist writers such as Catherine Clément and 愛蓮·西蘇 wrote in The Newly Born Woman from a place of opposition to the theories proposed in psychoanalytical works, pushing against the notion that socially constructed femininities and hysteria are natural to being female.[6][15] Feminist social historians of both genders argue that hysteria is caused by women's oppressed social roles, rather than by their bodies or psyches, and they have sought its sources in cultural myths of femininity and in male domination.[6]

參見

參考文獻

- Maines, Rachel P. . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1999: 23. ISBN 0-8018-6646-4.

- (In Western medicine;西醫)是指傳統醫學的歐洲醫學

- Mankiller, Wilma P.

. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. 1998: 26. ISBN 0-6180-0182-4.

. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. 1998: 26. ISBN 0-6180-0182-4. - Tasca, Cecilia; Rapetti, Mariangela; Carta, Mauro Giovanni; Fadda, Bianca. . Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2012-10-19, 8: 110–119. ISSN 1745-0179. PMC 3480686

. PMID 23115576. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010110.

. PMID 23115576. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010110. - Merskey, Harold; Potter, Paul. . British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989, 154 (6): 751–53. PMID 2688786. S2CID 38228923. doi:10.1192/bjp.154.6.751.

- Gilman, Sander L.; King, Helen; Porter, Roy; Rousseau, G.S.; Showalter, Elaine. . Los Angeles: University of California Press. 1993.

- King, Helen. . Gilman, Sander; King; Porter, Roy; Rousseau, G.S.; Showalter, Elaine (编). . University of California Press. 1993: 25. ISBN 0-520-08064-5.

- Flemming, Rebecca. . Oxford University Press. 2000. ISBN 0199240027.

- Roach, Mary. . New York: W.W. Norton & Co. 2009: 214. ISBN 9780393334791.

- Brogan, Boyd. . Representations (Berkeley, Calif.). 2019, 147 (1): 1–25 [2022-10-14]. ISSN 0734-6018. PMC 6814439

. PMID 31656366. doi:10.1525/rep.2019.147.1.1. (原始内容存档于2022-10-13).

. PMID 31656366. doi:10.1525/rep.2019.147.1.1. (原始内容存档于2022-10-13). - Spanos, Gottlieb, Nicholas, Jack. . Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979, 88 (5): 527–546. PMID 387849. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.88.5.527.

- Maines, Rachel. . Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1999.

- Schleiner, Winfried. . Georgetown University Press. 1995: 115.

- . www.medicalnewstoday.com. 2020-10-13 [2021-04-02]. (原始内容存档于2023-03-24) (英语).

- Devereux, Cecily. . eJournal. University of Alberta. March 2014 [October 20, 2016]. (原始内容存档于2016-12-20).

- Goetz, C.G. . Archives of Neurology. 1991, 48 (4): 421–25. PMID 2012518. doi:10.1001/archneur.1991.00530160091020.

- Jones, A. . New York: Routledge. 2010: 248–58, 300–08.

- Simon, Matt. . Wired. May 7, 2014 [November 28, 2014]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-05).

- Briggs L. . American Quarterly. 2000, 52 (2): 246–73. PMID 16858900. S2CID 8047730. doi:10.1353/aq.2000.0013.

- Morantz RM, Zschoche S. . Journal of American History. December 1980, 67 (3): 568–88. JSTOR 1889868. PMID 11614687. doi:10.2307/1889868.

- . embryo.asu.edu. [2021-04-02]. (原始内容存档于2023-03-27).

- Maines, Rachel. . bigthink.com. [16 November 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-09-05).

- King, Helen. (PDF). EuGeStA: Journal on Gender Studies in Antiquity. 2011, 1: 205–235 [2016-11-18]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-05-16).

- Hall, Lesley. . lesleyahall.net. [29 October 2016]. (原始内容存档于2018-09-28).

- Riddell, Fern. . 衛報. 10 November 2014 [29 October 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-15).

- Lieberman, Hallie; Schatzberg, Eric. (PDF). Journal of Positive Sexuality. 2018, 4 (2): 24–47 [2022-10-14]. doi:10.51681/1.421

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-08-15).

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-08-15). - Hollick, Frederick. . 1853.

- Micale MS. . Isis; an International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences. 1993, 84 (3): 496–526. JSTOR 235644. PMID 8282518. S2CID 37252994. doi:10.1086/356549.

- Micale MS. . The Harvard Mental Health Letter. July 2000, 17 (1): 4–6. PMID 10877868.

- . 2017 [2022-10-14]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-03).

- Coon, Mitterer, Dennis, John. . Cengage Learning. 2013: 512–513.

- Costa, Dayse Santos; Lang, Charles Elias. . Psicologia USP. 2016, 27 (1): 115–124. doi:10.1590/0103-656420140039

.

. - Pearson, Catherine. . HuffPost. 2013-11-21 [2021-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2022-12-20) (英语).

進一步閱讀

- Kapsalis, Terri (2008). The Hysterical Alphabet. WhiteWalls. ISBN 9780945323167.

- Libbrecht, Katrien. . London: Transaction Publishers. 1995. ISBN 1-56000-181-X.

- Micale, Mark S. . Princeton University Press. 1995. ISBN 0-691-03717-5.

- Micale, Mark S. . Harvard University Press. 2009-06-30. ISBN 9780674040984 (英语).

- Micklem, Niel. . Routledge. 1996. ISBN 0-415-12186-8.

- Bronfen, Elisabeth. . Princeton University Press. 2014-07-14. ISBN 9781400864737 (英语).

- Augsburg, Tanya. . UMI. 1996.

- Showalter, Elaine. . Virago. 1987. ISBN 978-0860688693.

- Lewis Herman, Judith.

. Basic Books. 1992. ISBN 978-0-465-08730-3.

. Basic Books. 1992. ISBN 978-0-465-08730-3.

外部連結

- Erika Kinetz, "Is Hysteria Real? Brain Images Say Yes" (页面存档备份,存于) (The New York Times)

- Female Hysteria during Victorian Era (页面存档备份,存于)