居里点

居里点(英語:),又作居里温度(Curie temperature,Tc)或磁性转变点。是指磁性材料中自发磁化强度降到零时的温度,是铁磁性或亚铁磁性物质转变成顺磁性物质的临界点。低于居里点温度时该物质成为铁磁体,此时和材料有关的磁场很难改变。当温度高于居里点时,该物质成为顺磁体,磁体的磁场很容易随周围磁场的改变而改变。这时的磁敏感度约为10-6。居里点由物质的化学成分和晶体结构决定。居里温度是以皮埃尔·居里命名的,他表明在临界温度下磁性材料会失去磁性。

居里點的溫度可以用平均場理論估計。

| 材料 | 居里 温度 (K) |

|---|---|

| 铁 (Fe) | 1043 |

| 钴 (Co) | 1400 |

| 镍 (Ni) | 627 |

| 钆 (Gd) | 292 |

| 镝 (Dy) | 88 |

| 铋化锰 (MnBi) | 630 |

| 锑化锰(MnSb) | 587 |

| 二氧化铬 (CrO2) | 386 |

| 砷化锰 | 318 |

| 氧化铕 | 69 |

| 氧化铁 (Fe2O3) | 948 |

| 四氧化三铁 (FeOFe2O3) | 858 |

| 氧化镍-氧化铁NiO–Fe2O3 | 858 |

| 氧化铜-氧化铁CuO–Fe2O3 | 728 |

| 氧化镁-氧化铁MgO–Fe2O3 | 713 |

| 氧化锰-氧化铁MnO–Fe2O3 | 573 |

| 钇铁石榴石 (Y3Fe5O12) | 560 |

| 钕磁铁 | 583—673 |

| 铝镍钴合金 | 973—1133 |

| 钐钴磁铁 | 993—1073 |

| 锶铁氧体 | 723 |

磁矩

磁矩是原子内的永久偶极矩,包含电子的角动量和自旋[4],他们之间的关系是 , me 是电子质量, μl 是磁矩, l是角动量; 这个比例被称作 gyromagnetic ratio(旋磁比).

原子中的电子从它们自己的角动量和它们围绕原子核的轨道动量贡献磁矩。与来自电子的磁矩相比,来自原子核的磁矩是微不足道的。[5] 热作用在更高能量的电子上结果就是扰乱了秩序,并破坏了偶极子之间的对齐。

铁磁性、顺磁性、亚铁磁性和反铁磁性材料有不同的固有磁矩结构。在材料特定的居里温度(TC)下,这些属性会发生变化。从反铁磁性到顺磁性(或反之亦然)的过渡发生在奈尔温度(TN), 这与居里温度类似。

| 低于TC | 高于TC |

|---|---|

| 铁磁性 | ↔ 顺磁性 |

| 亚铁磁性 | ↔ 顺磁性 |

| 低于TN | 高于TN |

| 反铁磁性 | ↔ 顺磁性 |

在居里温度下改变特性的具有磁矩的材料

铁磁性,顺磁性,亚铁磁性和反铁磁性结构由固有磁矩组成。 如果结构中的所有电子都配对,则由于它们的相反自旋和角动量,这些力矩会抵消。 因此,即使施加磁场,这些材料也具有不同的性质,并且没有居里温度。[6][7]

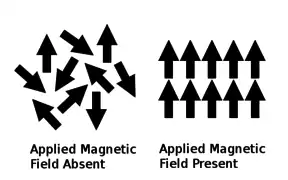

顺磁性

当一些材料的温度高于居里点时,材料会表现出顺磁性,这样的材料叫顺磁性材料。当没有受到外部磁场的影响时,顺磁性材料不会表现磁性;反之则会表现磁性。没有受到外部磁场影响时,材料内部的磁矩是无序排列的。也就是说,材料内部的粒子不整齐且没有顺磁力线方向排列。当受到磁场影响时,这些磁矩会顺磁场线整齐排列[8][9][10],并且产生感应磁场[10][11]。

对于顺磁性,这种对外加磁场的响应是正的,称为磁化率。[6] 磁化率仅适用于居里温度以上的无序状态。[12]

顺磁性的来源(具有居里温度的材料)包括:[13]

- 所有含未配对电子的原子;

- 内电子层未被填满的原子;

- 自由基;

- 金属。

超過居禮溫度後,原子被激發, 旋轉的方向變成隨機的[7] ,这种方向可以被作用場重新調整,此时即变为顺磁性。在居里温度以下,材料的固有结构经历了一次相变,[14] 原子变为有序,材料具有铁磁性。[10] 与铁磁性材料的磁场相比,顺磁性材料的感应磁场非常弱。[14]

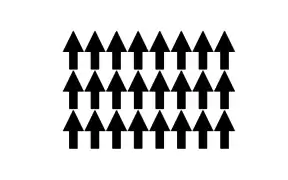

铁磁性

材料仅在其相应的居里温度以下具有铁磁性。在没有外加磁场的情况下,铁磁材料具有磁性。

当没有外加磁场时,材料具有自发磁化,这是有序磁矩的结果;也就是说,对于铁磁性材料,原子具有某种对称性并且在同一方向上排列,从而产生永久磁场。

磁性相互作用通过交换相互作用结合在一起;否则,热无序将克服磁矩的弱相互作用。交换相互作用的平行电子占据同一时间点的可能性为零,这意味着材料中会有一个倾向的平行排列。[15] 在这个过程中,玻尔兹曼因子贡献很大,因为它倾向于使相互作用的粒子在同一方向上排列。[16] 这会导致铁磁体具有较强的磁场和较高的居里温度,约 1000K(730℃)[17]

在居里温度以下,原子有序排列,从而导致自发磁性,材料具有铁磁性。在居里温度以上,该材料是顺磁性的,因为当该材料经历相变时,原子会失去其有序的磁矩。[14]

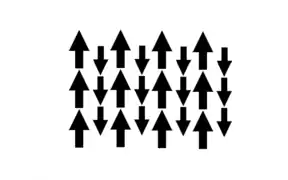

亚铁磁性

材料仅在其相应的居里温度以下具有亚铁磁性。在没有外加磁场的情况下,亚铁磁材料具有磁性,并由两种不同离子组成。[18]

当没有外加磁场时,材料具有自发磁化,这是有序磁矩的结果;也就是说,对于亚铁磁性材料,一种离子的磁矩对准一个方向,有一个大小,另一种离子的磁矩对准相反方向,有一个不同的大小。因为磁矩在相反的方向有着不同的大小,所以仍然有自发磁化,存在磁场。[18]

和铁磁性材料相似,磁性相互作用通过交换相互作用结合在一起。但是,磁矩的方向是反平行的,导致净势是一个减另一个。[18]

低于居里点时,每个离子的原子都反平行对齐,有着不同的磁矩,造成自发磁化;材料具有亚铁磁性。高于居里点时,该材料是顺磁性的,因为当该材料经历相变时,原子会失去其有序的磁矩。[18]

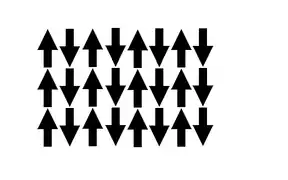

反铁磁性与奈尔温度

材料仅在其相应的奈尔温度以下具有反铁磁性。这与居里温度相似,高于奈尔温度时,该材料经历相变,变成顺磁性。也就是说,热能变得足够大,足以破坏材料内的微观磁有序性。 [19]它以路易·奈尔(Louis Néel,1904-2000 年)的名字命名,他因在该领域的工作而获得了 1970 年的诺贝尔物理学奖。

材料有方向相反的相等磁矩,导致在奈尔温度以下磁矩为零和净磁性为零。反铁磁性材料在有或没有外加磁场的情况下有很弱的磁性。

与铁磁性材料相似,磁性相互作用通过交换相互作用结合在一起;否则,热无序将克服磁矩的弱相互作用。[15][20]奈尔温度时无序出现。[20]

下面列表中有几种物质的奈尔温度:[21]

| Substance | Néel temperature (K) |

|---|---|

| MnO | 116 |

| MnS | 160 |

| MnTe | 307 |

| MnF2 | 67 |

| FeF2 | 79 |

| FeCl2 | 24 |

| FeI2 | 9 |

| FeO | 198 |

| FeOCl | 80 |

| CrCl2 | 25 |

| CrI2 | 12 |

| CoO | 291 |

| NiCl2 | 50 |

| NiI2 | 75 |

| NiO | 525 |

| KFeO2 | 983[22] |

| Cr | 308 |

| Cr2O3 | 307 |

| Nd5Ge3 | 50 |

居里 - 韦斯定律

居里-韦斯定律是居里定律的修正版本,是基于平均场论近似的简单模型,在材料温度T远高于其对应居里温度TC(即T ≫ TC)时较为适用,但却因原子间的局部波动作用无法在居里点附近对磁化率χ进行描述[23]。而T < TC的情况下,在居里定律和居里-韦斯定律均不成立。

Curie's law for a paramagnetic material:[24]

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| χ | the magnetic susceptibility; the influence of an applied magnetic field on a material |

| M | the magnetic moments per unit volume |

| H | the macroscopic magnetic field |

| B | the magnetic field |

| C | the material-specific Curie constant |

| Avagadro常数 | |

| µ0 | the permeability of free space. Note: in CGS units is taken to equal one.[26] |

| g | the Landé g-factor |

| J(J + 1) | the eigenvalue for eigenstate J2 for the stationary states within the incomplete atoms shells (electrons unpaired) |

| µB | the Bohr Magneton |

| kB | Boltzmann's constant |

| total magnetism | is N number of magnetic moments per unit volume |

The Curie–Weiss law is then derived from Curie's law to be:

where:

For full derivation see 居里-韦斯定律.

物理

从上方接近居里温度

As the Curie–Weiss law is an approximation, a more accurate model is needed when the temperature, T, approaches the material's Curie temperature, TC.

Magnetic susceptibility occurs above the Curie temperature.

An accurate model of critical behaviour for magnetic susceptibility with critical exponent γ:

The critical exponent differs between materials and for the mean-field model is taken as γ = 1.[28]

As temperature is inversely proportional to magnetic susceptibility, when T approaches TC the denominator tends to zero and the magnetic susceptibility approaches infinity allowing magnetism to occur. This is a spontaneous magnetism which is a property of ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials.[29][30]

从下方接近居里温度

Magnetism depends on temperature and spontaneous magnetism occurs below the Curie temperature. An accurate model of critical behaviour for spontaneous magnetism with critical exponent β:

The critical exponent differs between materials and for the mean-field model as taken as β = 1/2 where T ≪ TC.[28]

The spontaneous magnetism approaches zero as the temperature increases towards the materials Curie temperature.

接近绝对零度(0开尔文)

The spontaneous magnetism, occurring in ferromagnetic, ferrimagnetic and antiferromagnetic materials, approaches zero as the temperature increases towards the material's Curie temperature. Spontaneous magnetism is at its maximum as the temperature approaches 0 K.[31] That is, the magnetic moments are completely aligned and at their strongest magnitude of magnetism due to no thermal disturbance.

In paramagnetic materials temperature is sufficient to overcome the ordered alignments. As the temperature approaches 0 K, the 熵 decreases to zero, that is, the disorder decreases and becomes ordered. This occurs without the presence of an applied magnetic field and obeys the 热力学第三定律.[15]

Both Curie's law and the Curie–Weiss law fail as the temperature approaches 0 K. This is because they depend on the magnetic susceptibility which only applies when the state is disordered.[32]

硫酸钆 continues to satisfy Curie's law at 1 K. Between 0 and 1 K the law fails to hold and a sudden change in the intrinsic structure occurs at the Curie temperature.[33]

Ising相变模型

The Ising model is mathematically based and can analyse the critical points of phase transitions in ferromagnetic order due to spins of electrons having magnitudes of ±1/2. The spins interact with their neighbouring dipole electrons in the structure and here the Ising model can predict their behaviour with each other.[34][35]

This model is important for solving and understanding the concepts of phase transitions and hence solving the Curie temperature. As a result, many different dependencies that affect the Curie temperature can be analysed.

For example, the surface and bulk properties depend on the alignment and magnitude of spins and the Ising model can determine the effects of magnetism in this system.

Weiss磁畴和表面和体积居里温度

Materials structures consist of intrinsic magnetic moments which are separated into domains called Weiss domains.[36] This can result in ferromagnetic materials having no spontaneous magnetism as domains could potentially balance each other out.[36] The position of particles can therefore have different orientations around the surface than the main part (bulk) of the material. This property directly affects the Curie temperature as there can be a bulk Curie temperature TB and a different surface Curie temperature TS for a material.[37]

This allows for the surface Curie temperature to be ferromagnetic above the bulk Curie temperature when the main state is disordered, i.e. Ordered and disordered states occur simultaneously.[34]

The surface and bulk properties can be predicted by the Ising model and electron capture spectroscopy can be used to detect the electron spins and hence the magnetic moments on the surface of the material. An average total magnetism is taken from the bulk and surface temperatures to calculate the Curie temperature from the material, noting the bulk contributes more.[34][38]

The angular momentum of an electron is either +ħ/2 or −ħ/2 due to it having a spin of 1/2, which gives a specific size of magnetic moment to the electron; the Bohr magneton.[39] Electrons orbiting around the nucleus in a current loop create a magnetic field which depends on the Bohr Magneton and magnetic quantum number.[39] Therefore, the magnetic moments are related between angular and orbital momentum and affect each other. Angular momentum contributes twice as much to magnetic moments than orbital.[40]

For terbium which is a rare-earth metal and has a high orbital angular momentum the magnetic moment is strong enough to affect the order above its bulk temperatures. It is said to have a high anisotropy on the surface, that is it is highly directed in one orientation. It remains ferromagnetic on its surface above its Curie temperature while its bulk becomes ferrimagnetic and then at higher temperatures its surface remains ferrimagnetic above its bulk Néel Temperature before becoming completely disordered and paramagnetic with increasing temperature. The anisotropy in the bulk is different from its surface anisotropy just above these phase changes as the magnetic moments will be ordered differently or ordered in paramagnetic materials.[37]

更改材料的居里温度

Composite materials

Composite materials, that is, materials composed from other materials with different properties, can change the Curie temperature. For example, a composite which has silver in it can create spaces for oxygen molecules in bonding which decreases the Curie temperature[41] as the crystal lattice will not be as compact.

The alignment of magnetic moments in the composite material affects the Curie temperature. If the materials moments are parallel with each other the Curie temperature will increase and if perpendicular the Curie temperature will decrease[41] as either more or less thermal energy will be needed to destroy the alignments.

Preparing composite materials through different temperatures can result in different final compositions which will have different Curie temperatures.[42] Doping a material can also affect its Curie temperature.[42]

The density of nanocomposite materials changes the Curie temperature. Nanocomposites are compact structures on a nano-scale. The structure is built up of high and low bulk Curie temperatures, however will only have one mean-field Curie temperature. A higher density of lower bulk temperatures results in a lower mean-field Curie temperature and a higher density of higher bulk temperature significantly increases the mean-field Curie temperature. In more than one dimension the Curie temperature begins to increase as the magnetic moments will need more thermal energy to overcome the ordered structure.[38]

Particle size

The size of particles in a material's crystal lattice changes the Curie temperature. Due to the small size of particles (nanoparticles) the fluctuations of electron spins become more prominent, this results in the Curie temperature drastically decreasing when the size of particles decrease as the fluctuations cause disorder. The size of a particle also affects the anisotropy causing alignment to become less stable and thus lead to disorder in magnetic moments.[34][43]

The extreme of this is superparamagnetism which only occurs in small ferromagnetic particles and is where fluctuations are very influential causing magnetic moments to change direction randomly and thus create disorder.

The Curie temperature of nanoparticles are also affected by the crystal lattice structure, body-centred cubic (bcc), face-centred cubic (fcc) and a hexagonal structure (hcp) all have different Curie temperatures due to magnetic moments reacting to their neighbouring electron spins. fcc and hcp have tighter structures and as a results have higher Curie temperatures than bcc as the magnetic moments have stronger effects when closer together.[34] This is known as the coordination number which is the number of nearest neighbouring particles in a structure. This indicates a lower coordination number at the surface of a material than the bulk which leads to the surface becoming less significant when the temperature is approaching the Curie temperature. In smaller systems the coordination number for the surface is more significant and the magnetic moments have a stronger affect on the system.[34]

Although fluctuations in particles can be minuscule, they are heavily dependent on the structure of crystal lattices as they react with their nearest neighbouring particles. Fluctuations are also affected by the exchange interaction[43] as parallel facing magnetic moments are favoured and therefore have less disturbance and disorder, therefore a tighter structure influences a stronger magnetism and therefore a higher Curie temperature.

Pressure

Pressure changes a material's Curie temperature. Increasing pressure on the crystal lattice decreases the volume of the system. Pressure directly affects the kinetic energy in particles as movement increases causing the vibrations to disrupt the order of magnetic moments. This is similar to temperature as it also increases the kinetic energy of particles and destroys the order of magnetic moments and magnetism.[44]

Pressure also affects the density of states (DOS).[44] Here the DOS decreases causing the number of electrons available to the system to decrease. This leads to the number of magnetic moments decreasing as they depend on electron spins. It would be expected because of this that the Curie temperature would decrease however it increases. This is the result of the exchange interaction. The exchange interaction favours the aligned parallel magnetic moments due to electrons being unable to occupy the same space in time[15] and as this is increased due to the volume decreasing the Curie temperature increases with pressure. The Curie temperature is made up of a combination of dependencies on kinetic energy and the DOS.[44]

The concentration of particles also affects the Curie temperature when pressure is being applied and can result in a decrease in Curie temperature when the concentration is above a certain percent.[44]

Orbital ordering

Orbital ordering changes the Curie temperature of a material. Orbital ordering can be controlled through applied strains.[45] This is a function that determines the wave of a single electron or paired electrons inside the material. Having control over the probability of where the electron will be allows the Curie temperature to be altered. For example, the delocalised electrons can be moved onto the same plane by applied strains within the crystal lattice.[45]

The Curie temperature is seen to increase greatly due to electrons being packed together in the same plane, they are forced to align due to the exchange interaction and thus increases the strength of the magnetic moments which prevents thermal disorder at lower temperatures.

铁电材料中的居里温度

In analogy to ferromagnetic and paramagnetic materials, the term Curie temperature (TC) is also applied to the temperature at which a ferroelectric material transitions to being paraelectric. Hence, TC is the temperature where ferroelectric materials lose their spontaneous polarisation as a first or second order phase change occurs. In case of a second order transition the Curie Weiss temperature T0 which defines the maximum of the dielectric constant is equal to the Curie temperature. However, the Curie temperature can be 10 K higher than T0 in case of a first order transition.[46]

| Below TC | Above TC[47] |

|---|---|

| Ferroelectric | ↔ Dielectric (paraelectric) |

| Antiferroelectric | ↔ Dielectric (paraelectric) |

| Ferrielectric | ↔ Dielectric (paraelectric) |

| Helielectric | ↔ Dielectric (paraelectric) |

Ferroelectric and dielectric

Materials are only ferroelectric below their corresponding transition temperature T0.[48] Ferroelectric materials are all pyroelectric and therefore have a spontaneous electric polarisation as the structures are unsymmetrical.

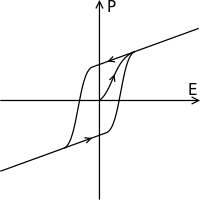

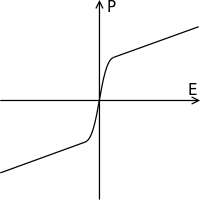

Ferroelectric materials' polarization is subject to hysteresis (Figure 4); that is they are dependent on their past state as well as their current state. As an electric field is applied the dipoles are forced to align and polarisation is created, when the electric field is removed polarisation remains. The hysteresis loop depends on temperature and as a result as the temperature is increased and reaches T0 the two curves become one curve as shown in the dielectric polarisation (Figure 5).[49]

相对介电常数

A modified version of the Curie–Weiss law applies to the dielectric constant, also known as the relative permittivity:[46][50]

应用

A heat-induced ferromagnetic-paramagnetic transition is used in magneto-optical storage media, for erasing and writing of new data. Famous examples include the Sony Minidisc format, as well as the now-obsolete CD-MO format. Curie point electro-magnets have been proposed and tested for actuation mechanisms in passive safety systems of fast breeder reactors, where control rods are dropped into the reactor core if the actuation mechanism heats up beyond the material's curie point.[51] Other uses include temperature control in soldering irons,[52] and stabilizing the magnetic field of tachometer generators against temperature variation.[53]

参考资料

引用

- Buschow 2001,p5021, table 1

- Jullien & Guinier 1989,第155頁

- Kittel 1986

- Hall & Hook 1994,第200頁

- Jullien & Guinier 1989,第136–38頁

- Ibach & Lüth 2009

- Levy 1968,第236–39頁

- Dekker 1958,第217–20頁

- Levy 1968

- Fan 1987,第164–65頁

- Dekker 1958,第454–55頁

- Mendelssohn 1977,第162頁

- Levy 1968,第198–202頁

- Cusack 1958,第269頁

- Hall & Hook 1994,第220–21頁

- Palmer 2007

- Hall & Hook 1994,第220頁

- Jullien & Guinier 1989,第158–59頁

- Spaldin, Nicola A. Repr. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. 2006: 89–106. ISBN 9780521016582.

- Jullien & Guinier 1989,第156–57頁

- Kittel, Charles. 8th. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 2005. ISBN 978-0-471-41526-8.

- Ichida, Toshio. . Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan. 1973, 46 (1): 79–82. doi:10.1246/bcsj.46.79

.

. - Jullien & Guinier 1989,第153頁

- Hall & Hook 1994,第205–06頁

- Levy 1968,第201–02頁

- Kittel 1996,第444頁

- Myers 1997,第334–45頁

- Hall & Hook 1994,第227–28頁

- Kittel 1986,第424–26頁

- Spaldin 2010,第52–54頁

- Hall & Hook 1994,第225頁

- Mendelssohn 1977,第180–81頁

- Mendelssohn 1977,第167頁

- Bertoldi, Bringa & Miranda 2012

- Brout 1965,第6–7頁

- Jullien & Guinier 1989,第161頁

- Rau, Jin & Robert 1988

- Skomski & Sellmyer 2000

- Jullien & Guinier 1989,第138頁

- Hall & Hook 1994

- Hwang et al. 1998

- Paulsen et al. 2003

- López Domínguez et al. 2013

- Bose et al. 2011

- Sadoc et al. 2010

- Webster 1999

- Kovetz 1990,第116頁

- Myers 1997,第404–05頁

- Pascoe 1973,第190–91頁

- Webster 1999,第6.55–6.56頁

- Takamatsu. . Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology.

- TMT-9000S

- Pallàs-Areny & Webster 2001,第262–63頁

来源

- Buschow, K. H. J. . Elsevier. 2001. ISBN 0-08-043152-6.

- Kittel, Charles. 6th. John Wiley & Sons. 1986. ISBN 0-471-87474-4.

- Pallàs-Areny, Ramon; Webster, John G. 2nd. John Wiley & Sons. 2001. ISBN 978-0-471-33232-9.

- Spaldin, Nicola A. 2nd. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010. ISBN 9780521886697.

- Ibach, Harald; Lüth, Hans. 4th. Berlin: Springer. 2009. ISBN 9783540938033.

- Levy, Robert A. . Academic Press. 1968. ISBN 978-0124457508.

- Fan, H. Y. . Wiley-Interscience. 1987. ISBN 9780471859871.

- Dekker, Adrianus J. . Macmillan. 1958. ISBN 9780333106235.

- Cusack, N. . Longmans, Green. 1958.

- Hall, J. R.; Hook, H. E. 2nd. Chichester: Wiley. 1994. ISBN 0471928054.

- Jullien, André; Guinier, Rémi. . Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. 1989. ISBN 0198555547.

- Mendelssohn, K. . with S.I. units. 2nd. London: Taylor and Francis. 1977. ISBN 0850661196.

- Myers, H. P. 2nd. London: Taylor & Francis. 1997. ISBN 0748406603.

- Kittel, Charles. 7th. New York [u.a.]: Wiley. 1996. ISBN 0471111813.

- Palmer, John. Online. Boston: Birkhäuser. 2007. ISBN 9780817646202.

- Bertoldi, Dalía S.; Bringa, Eduardo M.; Miranda, E. N. . Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. May 2012, 24 (22): 226004 [12 February 2013]. Bibcode:2012JPCM...24v6004B. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/24/22/226004.

- Brout, Robert. . New York, Amsterdam: W. A. Benjamin, Inc. 1965.

- Rau, C.; Jin, C.; Robert, M. . Journal of Applied Physics. 1988, 63 (8): 3667. Bibcode:1988JAP....63.3667R. doi:10.1063/1.340679.

- Skomski, R.; Sellmyer, D. J. . Journal of Applied Physics. 2000, 87 (9): 4756. Bibcode:2000JAP....87.4756S. doi:10.1063/1.373149.

- López Domínguez, Victor; Hernàndez, Joan Manel; Tejada, Javier; Ziolo, Ronald F. . Chemistry of Materials. 14 November 2012, 25 (1): 6–11. doi:10.1021/cm301927z.

- Bose, S. K.; Kudrnovský, J.; Drchal, V.; Turek, I. . Physical Review B. 18 November 2011, 84 (17). Bibcode:2011PhRvB..84q4422B. arXiv:1010.3025

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.84.174422.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.84.174422. - Webster, John G. (编). Online. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press published in cooperation with IEEE Press. 1999. ISBN 0849383471.

- Whatmore, R. W. 2nd. New York, NY: Springer. 1991. ISBN 978-1-4613-6703-1.

- Kovetz, Attay. 1st. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 1990. ISBN 0-521-39997-1.

- Hummel, Rolf E. 3rd. New York [u.a.]: Springer. 2001. ISBN 0-387-95144-X.

- Pascoe, K. J. . New York, N.Y.: J. Wiley and Sons. 1973. ISBN 0471669113.

- Paulsen, J. A.; Lo, C. C. H.; Snyder, J. E.; Ring, A. P.; Jones, L. L.; Jiles, D. C. . IEEE Transactions on Magnetics. 23 September 2003, 39 (5): 3316–18. Bibcode:2003ITM....39.3316P. ISSN 0018-9464. doi:10.1109/TMAG.2003.816761.

- Hwang, Hae Jin; Nagai, Toru; Ohji, Tatsuki; Sando, Mutsuo; Toriyama, Motohiro; Niihara, Koichi. . Journal of the American Ceramic Society. March 1998, 81 (3): 709–12. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1998.tb02394.x.

- Sadoc, Aymeric; Mercey, Bernard; Simon, Charles; Grebille, Dominique; Prellier, Wilfrid; Lepetit, Marie-Bernadette. . Physical Review Letters. 2010, 104 (4): 046804. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104d6804S. PMID 20366729. arXiv:0910.3393

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.046804.

. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.046804. - Kochmański, Martin; Paszkiewicz, Tadeusz; Wolski, Sławomir. . European Journal of Physics. 2013, 34: 1555–73. Bibcode:2013EJPh...34.1555K. arXiv:1301.2141

. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/34/6/1555.

. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/34/6/1555. - . Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB. 2014 [14 March 2013]. (原始内容存档于2018-08-10).

- . thermaltronics.com. [13 January 2016]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-21).