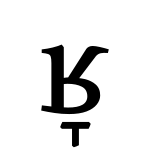

| Voiced uvular fricative | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ʁ | |||

| IPA Number | 143 | ||

| Audio sample | |||

|

source · help | |||

| Encoding | |||

| Entity (decimal) | ʁ | ||

| Unicode (hex) | U+0281 | ||

| X-SAMPA | R | ||

| Braille | |||

| |||

| Voiced uvular approximant | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ʁ̞ | |||

| IPA Number | 144 | ||

| Audio sample | |||

|

source · help | |||

| Encoding | |||

| X-SAMPA | R_o | ||

| |||

| Labialized voiced uvular approximant | |

|---|---|

| ʁʷ |

The voiced uvular fricative is a type of consonantal sound, used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨ʁ⟩, an inverted small uppercase letter ⟨ʀ⟩, or in broad transcription ⟨r⟩ if rhotic. This consonant is one of the several collectively called guttural R when found in European languages.

The voiced uvular approximant is also found interchangeably with the fricative, and may also be transcribed as ⟨ʁ⟩. Because the IPA symbol stands for the uvular fricative, the approximant may be specified by adding the downtack: ⟨ʁ̞⟩, though some writings[1] use a superscript ⟨ʶ⟩, which is not an official IPA practice.

For a voiced pre-uvular fricative (also called post-velar), see voiced velar fricative.

Features

Features of the voiced uvular fricative:

- Its manner of articulation is fricative, which means it is produced by constricting air flow through a narrow channel at the place of articulation, causing turbulence. In many languages it is closer to an approximant, however, and no language distinguishes the two at the uvular articulation.

- Its place of articulation is uvular, which means it is articulated with the back of the tongue (the dorsum) at the uvula.

- Its phonation is voiced, which means the vocal cords vibrate during the articulation.

- It is an oral consonant, which means air is allowed to escape through the mouth only.

- It is a central consonant, which means it is produced by directing the airstream along the center of the tongue, rather than to the sides.

- The airstream mechanism is pulmonic, which means it is articulated by pushing air solely with the intercostal muscles and abdominal muscles, as in most sounds.

Occurrence

In Western Europe, a uvular trill pronunciation of rhotic consonants spread from northern French to several dialects and registers of Basque,[2] Catalan, Danish, Dutch, German, Judaeo-Spanish, Norwegian, Occitan, Portuguese, Swedish, some variants of Low Saxon,[3] and Yiddish. However, not all of them remain a uvular trill today. In Brazilian Portuguese, it is usually a velar fricative ([x], [ɣ]), voiceless uvular fricative [χ], or glottal transition ([h], [ɦ]), except in southern Brazil, where alveolar, velar and uvular trills as well as the voiced uvular fricative predominate. Because such uvular rhotics often do not contrast with alveolar ones, IPA transcriptions may often use ⟨r⟩ to represent them for ease of typesetting. For more information, see guttural R.

Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996) note, "There is... a complication in the case of uvular fricatives in that the shape of the vocal tract may be such that the uvula vibrates."[4]

It is also present in most Turkic languages, except for Turkish, and in Caucasian languages. It could also come in ɣ.

| Language | Word | IPA | Meaning | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abkhaz | цыҕ cëğ | [tsəʁ] | 'marten' | See Abkhaz phonology | |

| Adyghe | тыгъэ tëğa | ⓘ | 'sun' | ||

| Afrikaans | Parts of the former Cape Province[5] | rooi | [ʁoːi̯] | 'red' | May be a trill [ʀ] instead.[5] See Afrikaans phonology |

| Albanian | Arbëresh

Some Moresian accents |

vëlla | [vʁa] | 'brother' | May be pronounced as a normal double l. Sometimes, the guttural r is present in words starting with g in some dialects. |

| Aleut | Atkan dialect | chamĝul | [tʃɑmʁul] | 'to wash' | |

| Arabic | Modern Standard[6] | غرفة ġurfa | [ˈʁʊrfɐ] | 'room' | Mostly transcribed as /ɣ/, may be velar, post-velar or uvular, depending on dialect.[7] See Arabic phonology |

| Archi[8] | гъӀабос ġabos | [ʁˤabos][9] | 'croak' | ||

| Armenian | ղեկ łek | ⓘ | 'rudder' | ||

| Asturian language | Most common allophone of /g/. May be an approximant.[10][11] | ||||

| Avar | тIагъур thaġur | [tʼaˈʁur] | 'cap' | ||

| Bashkir | туғыҙ tuğïð | ⓘ | 'nine' | ||

| Basque | Northern dialects | urre | [uʁe] | 'gold' | |

| Chilcotin | relkɨsh | [ʁəlkɪʃ] | 'he walks' | ||

| Danish | Standard[12] | rød | [ʁ̞œ̠ð̠] | 'red' | Most often an approximant when initial.[13] In other positions, it can be either a fricative (also described as voiceless [χ]) or an approximant.[12] Also described as pharyngeal [ʕ̞].[14] It can be a fricative trill in word-initial positions when emphasizing a word.[15] See Danish phonology |

| Dutch[16][17][18][19] | Belgian Limburg[20][21] | rad | [ʁɑt] | 'wheel' | Either a fricative or an approximant.[18][20][19][17][22] Realization of /r/ varies considerably among dialects. See Dutch phonology |

| Central Netherlands[23] | |||||

| East Flanders[21] | |||||

| Northern Netherlands[23] | |||||

| Randstad[23] | |||||

| Southern Netherlands[23] | |||||

| English | Dyfed[24] | red | [ʁɛd] | 'red' | Not all speakers.[24] Alveolar in other Welsh accents. |

| Gwynedd[24] | |||||

| North-east Leinster[25] | Corresponds to [ɹ ~ ɾ ~ ɻ] in other dialects of English in Ireland. | ||||

| Northumbrian[26][27] | Described both as a fricative[26] and an approximant.[27] More rarely it is a trill [ʀ].[26] Mostly found in rural areas of Northumberland and northern County Durham, declining. See English phonology and Northumbrian Burr. | ||||

| Sierra Leonean[26] | More rarely a trill [ʀ].[26] | ||||

| French | rester | ⓘ | 'to stay' | See French phonology | |

| German | Standard[28] | Rost | [ʁɔstʰ] | 'rust' | Either a fricative or, more often, an approximant. In free variation with a uvular trill. See Standard German phonology |

| Lower Rhine[28] | |||||

| Swabian[29] | [ʁ̞oʃt] | An approximant.[29] It is the realization of /ʁ/ in onsets,[29] otherwise it is an epiglottal approximant.[29] | |||

| Gondi | Hill-Maṛia | pār̥- | [paːʁ-] | 'to sing' | Corresponds to /r/ or /ɾ/ in other Gondi dialects. |

| Hebrew | Biblical | עוֹרֵב | [ʕoˈreβ] | 'raven' | See Biblical Hebrew phonology. |

| Modern | עוֹרֵב | [ʔoˈʁ̞ev] | See Modern Hebrew phonology.[30] | ||

| Inuktitut | East Inuktitut dialect | marruuk | [mɑʁːuːk] | 'two' | |

| Italian | Some speakers[31] | raro | [ˈʁäːʁo] | 'rare' | Rendition alternative to the standard Italian alveolar trill [r], due to individual orthoepic defects and/or regional variations that make the alternative sound more prevalent, notably in Alto Adige (bordering with German-speaking Austria), Val d'Aosta (bordering with France) and in parts of the Parma province, more markedly around Fidenza. Other alternative sounds may be a uvular trill [ʀ] or a labiodental approximant [ʋ].[31] See Italian phonology. |

| Kabardian | бгъэ bğa | ⓘ | 'eagle' | ||

| Kabyle | ⴱⴻⵖ bbeɣ بغ | [bːəʁ] | 'to dive' | ||

| Kazakh | саған, sağan | [sɑˈʁɑn] | 'to you' | ||

| Kyrgyz | жамгыр camğır' | [dʒɑmˈʁɯr] | 'rain' | ||

| Lakota | aǧúyapi | [aʁʊjapɪ] | 'bread' | ||

| Limburgish | Maastrichtian[32] | drei | [dʀ̝ɛi̯] | 'three' | Fricative trill; the fricative component varies between uvular and post-velar.[32][33] See Maastrichtian dialect phonology and Weert dialect phonology |

| Weert dialect[33] | drej | [dʀ̝æj] | |||

| Luxembourgish[34] | Parmesan | [ˈpʰɑʁməzaːn] | 'Parmesan' | Appears as an allophone of /ʀ/ between a vowel and a voiced consonant and as an allophone of /ʁ/ between a back vowel and another vowel (back or otherwise). A minority of speakers use it as the only consonantal variety of /ʀ/ (in a complementary distribution with [χ]), also where it is trilled in the standard language.[34] See Luxembourgish phonology | |

| Malay | Perak dialect | Perak | [peʁɑk̚] | 'Perak' | See Malay phonology |

| Malto[35] | पोग़े | [poʁe] | 'smoke' | ||

| Norwegian | Southern dialects | rar | [ʁ̞ɑːʁ̞] | 'strange' | Either an approximant or a fricative. See Norwegian phonology |

| Southwestern dialects | |||||

| Toba qom | Takshek dialect | Awo |

[awoʁojk] | 'moon' | |

| Tundra Nenets | Some speakers | вара | [waʁa] | 'goose' | |

| Ossetic | Iron | æгъгъæд æğğæd | [ˈəʁːəd] | 'enough' | |

| Portuguese | European[36] | carro | [ˈkaʁu] | 'car' | Word-initial /ʁ/ is commonly realized as a fricative trill in Lisbon.[15] See Portuguese phonology |

| Setubalense[37] | ruralizar | [ʁuʁɐɫiˈzaʁ] | 'to ruralize' | Outcome of a merger of /ɾ/ with /ʁ/, which is unique in the Lusophone world. Often trilled instead. | |

| Fluminense[37][38] | ardência | [ɐʁˈdẽsjə] | 'burning feeling' | Due to 19th century Portuguese influence, Rio de Janeiro's dialect merged coda /ɾ/ into /ʁ/.[39] Often trilled. In free variation with [ɣ], [ʕ] and [ɦ] before voiced sounds, [x], [χ], [ħ] and [h] before voiceless consonants | |

| Sulista | arroz | [ɐˈʁos] | 'rice' | ||

| Spanish | Puerto Rican | carro | [ˈkaʁo] | 'car' | Word-initial, and inter-vocallic double r ('rr') /r/ are commonly realized as a fricative trill in rural sectors and generally (but not exclusively) lower socioeconomic strata among Puerto Ricans. [ʁ].[40] |

| As spoken in Asturias | gusano | [ʁ̞uˈsano] | 'worm' | Most common allophone of /g/. May also be an approximant.[10][11] | |

| Swedish | Southern dialects | rör | [ʁɶʁ] | 'pipe(s)' | See Swedish phonology |

| Tatar | яңгыр, yañğır | [jɒŋˈʁɯr] | 'rain' | ||

| Turkmen | aɡyr | [ɑɡɨɾ] | 'heavy' | An allophone of /ɣ/ next to back vowels | |

| Tsez | агъи aɣi | [ˈʔaʁi] | 'bird' | ||

| Ubykh | [ʁa] | 'his' | Ubykh has ten different uvular fricatives. See Ubykh phonology | ||

| Uyghur | ئۇيغۇر | [ʊjʁʊr] | 'Uyghur' | ||

| Uzbek | ogʻir | [ɒˈʁɨr] | 'heavy' | ||

| West Flemish | Bruges dialect[41] | onder | [ˈuŋəʀ̝] | 'under' | A fricative trill with little friction. An alveolar [r] is used in the neighbouring rural area.[41] |

| Yakut | тоҕус toğus | [toʁus] | 'nine' | ||

See also

Notes

- ↑ Such as Krech et al. (2009).

- ↑ Grammar of Basque, page 30, José Ignacio Hualde, Jon Ortiz De Urbina, Walter de Gruyter, 2003

- ↑ Ph Bloemhoff-de Bruijn, Anderhalve Eeuw Zwols Vocaalveranderingsprocessen in de periode 1838-1972. IJsselacademie (2012). ISBN 978-90-6697-228-5

- ↑ Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:167)

- 1 2 Donaldson (1993), p. 15.

- ↑ Watson (2002), pp. 17.

- ↑ Watson (2002), pp. 17, 19–20, 35-36 and 38.

- ↑ "The Archi Language Tutorial" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

- ↑ "Dictionary of Archi". Retrieved 2023-12-10.

- 1 2 Muñiz Cachón, Carmen (2002). "Realización del fonema /g/ en Asturias". Revista de Filoloxía Asturiana (in Spanish). 2: 53–70. doi:10.17811/rfa.2.2002.

- 1 2 Muñiz Cachón, Carmen (2002). "Rasgos fónicos del español hablado en Asturias". Archivum: Revista de la Facultad de Filología (in Spanish). 52: 323–349.

- 1 2 Basbøll (2005:62)

- ↑ Basbøll (2005:66)

- ↑ Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:323)

- 1 2 Grønnum (2005), p. 157.

- ↑ Booij (1999:8)

- 1 2 Collins & Mees (2003:39, 54, 179, 196, 199–201, 291)

- 1 2 Goeman & van de Velde (2001:91–92, 94–95, 97, 99, 101–104, 107–108)

- 1 2 Verstraten & van de Velde (2001:51–55)

- 1 2 Verhoeven (2005:245)

- 1 2 Verstraten & van de Velde (2001:52)

- ↑ Goeman & van de Velde (2001:91–92, 94–95, 97, 102)

- 1 2 3 4 Verstraten & van de Velde (2001:54)

- 1 2 3 Wells (1982:390)

- ↑ Hickey (2007:?)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ladefoged & Maddieson (1996:236)

- 1 2 Ogden (2009:93)

- 1 2 Hall (1993:89)

- 1 2 3 4 Markus Hiller. "Pharyngeals and "lax" vowel quality" (PDF). Mannheim: Institut für Deutsche Sprache. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-28. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- ↑ The pronunciation of the Modern Hebrew consonant ר resh has been described as a uvular approximant ʁ, specifically [ʁ̞], which also exists in Yiddish, see Ghil'ad Zuckermann (2003), Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 261-262.

- 1 2 Canepari (1999), pp. 98–101.

- 1 2 Gussenhoven & Aarts (1999), p. 156.

- 1 2 Heijmans & Gussenhoven (1998), p. 108.

- 1 2 Gilles & Trouvain (2013), p. 68.

- ↑ Bhadriraju Krishnamurti (2003), p. 150.

- ↑ Cruz-Ferreira (1995:92)

- 1 2 (in Portuguese) Rhotic consonants in the speech of three municipalities of Rio de Janeiro: Petrópolis, Itaperuna and Paraty. Page 11.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) The process of Norm change for the good pronunciation of the Portuguese language in chant and dramatics in Brazil during 1938, 1858 and 2007 Archived 2016-02-06 at the Wayback Machine Page 36.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) The acoustic-articulatory path of the lateral palatal consonant's allophony. Pages 229 and 230.

- ↑ Lipski (1994:333)

- 1 2 Hinskens & Taeldeman (2013), p. 167.

References

- Basbøll, Hans (2005), The Phonology of Danish, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-203-97876-5

- Booij, Geert (1999), The phonology of Dutch, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-823869-X

- Collins, Beverley; Mees, Inger M. (2003) [First published 1981], The Phonetics of English and Dutch (5th ed.), Leiden: Brill Publishers, ISBN 9004103406

- Cruz-Ferreira, Madalena (1995), "European Portuguese", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 25 (2): 90–94, doi:10.1017/S0025100300005223, S2CID 249414876

- Donaldson, Bruce C. (1993), "1. Pronunciation", A Grammar of Afrikaans, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 1–35, ISBN 9783110134261

- Dum-Tragut, Jasmine (2009), Armenian: Modern Eastern Armenian, Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company

- Gilles, Peter; Trouvain, Jürgen (2013), "Luxembourgish", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 43 (1): 67–74, doi:10.1017/S0025100312000278

- Goeman, Ton; van de Velde, Hans (2001). "Co-occurrence constraints on /r/ and /ɣ/ in Dutch dialects". In van de Velde, Hans; van Hout, Roeland (eds.). 'r-atics. Brussels: Etudes & Travaux. pp. 91–112. ISSN 0777-3692.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Grønnum, Nina (2005), Fonetik og fonologi, Almen og Dansk (3rd ed.), Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag, ISBN 87-500-3865-6

- Gussenhoven, Carlos; Aarts, Flor (1999), "The dialect of Maastricht" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, University of Nijmegen, Centre for Language Studies, 29 (2): 155–166, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006526, S2CID 145782045

- Hall, Tracy Alan (1993), "The phonology of German /ʀ/", Phonology, 10 (1): 83–105, doi:10.1017/S0952675700001743, S2CID 195707076

- Heijmans, Linda; Gussenhoven, Carlos (1998), "The Dutch dialect of Weert" (PDF), Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 28 (1–2): 107–112, doi:10.1017/S0025100300006307, S2CID 145635698

- Hickey, Raymond (2007). Irish English: History and Present-day Forms. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85299-9.

- Hinskens, Frans; Taeldeman, Johan, eds. (2013), Dutch, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018005-3

- Kachru, Yamuna (2006), Hindi, John Benjamins Publishing, ISBN 90-272-3812-X

- Krech, Eva Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz-Christian (2009), Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19815-6.

- Lipski, John (1994), Latin American Spanish, London: Longman, ISBN 9780582087613

- Ogden, Richard (2009), An Introduction to English Phonetics, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd., ISBN 978-0-7486-2540-6

- Sjoberg, Andrée F. (1963), Uzbek Structural Grammar, Uralic and Altaic Series, vol. 18, Bloomington: Indiana University

- Verhoeven, Jo (2005), "Belgian Standard Dutch", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 35 (2): 243–247, doi:10.1017/S0025100305002173

- Verstraten, Bart; van de Velde, Hans (2001). "Socio-geographical variation of /r/ in standard Dutch". In van de Velde, Hans; van Hout, Roeland (eds.). 'r-atics. Brussels: Etudes & Travaux. pp. 45–61. ISSN 0777-3692.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Watson, Janet C. E. (2002), The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic, New York: Oxford University Press

- Wells, John C. (1982), Accents of English, vol. 2: The British Isles, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.