| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

The history of Australia from 1901 to 1945 begins with the federation of the six colonies to create the Commonwealth of Australia. The young nation joined Britain in the First World War, suffered through the Great Depression in Australia as part of the global Great Depression and again joined Britain in the Second World War against Nazi Germany in 1939. Imperial Japan launched air raids and submarine raids against Australian cities during the Pacific War.

Federation

The First Fleet of British ships had arrived at Sydney Harbour in 1788, founding the first of what would evolve into six self-governed British colonies: New South Wales, Tasmania, South Australia, Western Australia, Victoria and Queensland. The last British garrisons had left Australia in 1870.[1] At the beginning of the 20th century nearly two decades of negotiations on Federation concluded, with the approval of a federal constitution by all six British colonies’ parliaments in Australia and its subsequent ratification by the British parliament in 1900. This resulted in the political integration of the six British colonies in Australia into one federated Australian Commonwealth, formally proclaimed on 1 January 1901.

Melbourne was chosen as the temporary seat of government while a purpose-designed capital city, Canberra, was constructed. The future King George V, then the Duke of York, opened the first Parliament of Australia on 9 May 1901, and his successor (later to be King George VI) opened the first session in Canberra during May 1927. Australia became officially autonomous in both internal and external affairs with the passage of the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act on 9 October 1942. The Australia Act 1986 eliminated the last vestiges of British legal authority at the Federal level. (The last state to remove recourse to British courts, Queensland, did not do so until 1988).

Early 20th century

The Commonwealth of Australia came into being when the Federal Constitution was proclaimed by the Governor General, Lord Hopetoun, on 1 January 1901. The first Federal elections were held in March 1901 and resulted in a narrow majority for the Protectionist Party over the Free Trade Party with the Australian Labor Party (ALP) polling third. Labor declared it would offer support to the party which offered concessions and Edmund Barton's Protectionists formed a government, with Alfred Deakin as Attorney-General.[2]

Barton promised to "create a high court,... and an efficient federal public service.... He proposed to extend conciliation and arbitration, create a uniform railway gauge between the eastern capitals,[3] to introduce female federal franchise, to establish a... system of old age pensions."[4] He also promised to introduce legislation to safeguard "White Australia" from any influx of Asian or Pacific Island labour.

The Labor Party (the spelling "Labour" was dropped in 1912) had been established in the 1890s, after the failure of the Maritime and Shearer's strikes. Its strength was in the Australian Trade Union movement "which grew from a membership of just under 100,000 in 1901 to more than half a million in 1914."[5] The platform of the ALP was democratic socialist. Its rising support at elections, together with its formation of federal government in 1904 under Chris Watson, and again in 1908, helped to unify competing conservative, free market and liberal anti-socialists into the Commonwealth Liberal Party in 1909. Although this party dissolved in 1916, a successor to its version of "liberalism" in Australia which in some respects comprises an alliance of Millsian liberals and Burkian conservatives united in support for individualism and opposition to socialism can be found in the modern Liberal Party.[6] To represent rural interests, the Country Party (today's National Party) was founded in 1913 in Western Australia, and nationally in 1920, from a number of state-based farmer's parties.[7][8]

In writing about the preoccupations of the Australian population in early Federation Australia prior to World War One, the official Great War historian Charles Bean included the "White Australia Policy", which he defined as "a vehement effort to maintain a high Western standard of economy, society and culture (necessitating at that stage, however it might be camouflaged, the rigid exclusion of Oriental peoples)."[1] The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was one of the first laws passed by the new Australian parliament. Aimed to restrict immigration from Asia (especially China), it found strong support in the national parliament, arguments ranging from economic protection to outright racism.[9] The law permitted a dictation test in any European language to be used to in effect exclude non-"white" immigrants. The ALP wanted to protect "white" jobs and pushed for more explicit restrictions. A few politicians spoke of the need to avoid hysterical treatment of the question. Member of Parliament Bruce Smith said he had "no desire to see low-class Indians, Chinamen or Japanese... swarming into this country.... But there is obligation...not (to) unnecessarily offend the educated classes of those nations."[10] Donald Cameron, a member from Tasmania, expressed a rare note of dissension:

[N]o race on... this earth has been treated in a more shameful manner than have the Chinese.... They were forced at the point of a bayonet to admit Englishmen... into China. Now if we compel them to admit our people... why in the name of justice should we refuse to admit them here?[11]

Outside parliament, Australia's first Catholic cardinal, Patrick Francis Moran was politically active and denounced anti-Chinese legislation as "unchristian".[12] The popular press mocked the cardinal's position and the small European population of Australia generally supported the legislation and remained fearful of being overwhelmed by an influx of non-British migrants from the vastly different cultures of the highly populated empires to Australia's north.

The law passed both houses of Parliament and remained a central feature of Australia's immigration laws until abandoned in the 1950s. In the 1930s, the Lyons government unsuccessfully attempted to exclude Egon Kisch, a Czechoslovakian communist author from entering Australia by means of a 'dictation test' in Scottish Gaelic. The High Court of Australia ruled against this usage, and concerns emerged that the law could be used for such political purposes.[13][14]

Before 1901, units of soldiers from all six Australian colonies had been active as part of British forces in the Boer War. When the British government asked for more troops from Australia in early 1902, the Australian government obliged with a national contingent. Some 16,500 men had volunteered for service by the war's end in June 1902.[15] But Australians soon felt vulnerable closer to home. The Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 "allowed the Royal Navy to withdraw its capital ships from the Pacific by 1907. Australians saw themselves in time of war a lonely, sparsely populated outpost."[16] The impressive visit of the US Navy's Great White Fleet in 1908 emphasised to the government the value of an Australian navy. The Defence Act of 1909 reinforced the importance of Australian defence, and in February 1910, Lord Kitchener provided further advice on a defence scheme based on conscription. By 1913, the battlecruiser Australia led the fledgling Royal Australian Navy. Historian Bill Gammage estimates on the eve of war, Australia had 200,000 men "under arms of some sort".[16]

Historian Humphrey McQueen has it that working and living conditions for Australia's working classes in the early 20th century were of "frugal comfort."[17] While the establishment of an Arbitration court for Labour disputes was divisive, it was an acknowledgement of the need to set Industrial awards, where all wage earners in one industry enjoyed the same conditions of employment and wages. The Harvester Judgment of 1907 recognised the concept of a basic wage and in 1908 the Federal government also began an old age pension scheme. Thus the new Commonwealth gained recognition as a laboratory for social experimentation and positive liberalism.[2]

Catastrophic droughts plagued some regions in the late 1890s and early 20th century and together with a growing rabbit plague, created great hardship in rural Australia. Despite this, a number of writers "imagined a time when Australia would outstrip Britain in wealth and importance, when its open spaces would support rolling acres of farms and factories to match those of the United States. Some estimated the future population at 100 million, 200 million or more."[18] Amongst these was E. J. Brady, whose 1918 book Australia Unlimited described Australia's inland as ripe for development and settlement, "destined one day to pulsate with life."[19]

Religion

In the early years of the century the Church of England in Australia transformed itself in its patterns of worship, in the internal appearances of its churches, and in the forms of piety recommended by its clergy. The changes represented a heightened emphasis on the sacraments and were introduced by younger clergy trained in England and inspired by the Oxford and Anglo-Catholic movements. The church's women and its upper and middle class parishes were most supportive, overcoming the reluctance of some of the men. The changes were widely adopted by the 1920s, making the Church of England more self-consciously "Anglican" and distinct from other Protestant churches.[20][21] Controversy erupted, especially in New South Wales, between the politically liberal proponents of the Social Gospel, who wanted more Church attention to the social ills of society, and conservative elements. The opposition of the strong conservative evangelical forces within the Sydney diocese limited the liberals during the 1930s, but their ideas contributed to the formation of the influential post-World War II Christian Social Order Movement.[22]

Attempts to unite the Congregationalist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches failed in 1901–13 and again in 1917–25; they succeeded only in 1977, with the organisation of the Uniting Church in Australia. The efforts early in the century were impeded by weak organisation within each denomination. Interdenominational differences over organisation, the status of the ministry, and (to a lesser extent) doctrine also stood in the way. By 1920, the theological liberalism of unionist leaders made the entire movement suspect to orthodox members, especially Presbyterians. Most important was the opposition and apathy of the general membership of the churches. The leaders who designed plans for union had ignored the laity in the decision-making process and had failed to develop practical co-operation at the local level.[23]

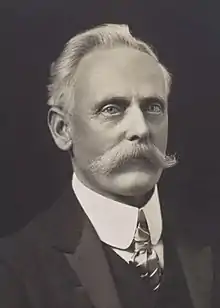

So in Australia's Catholic Church was based, until fairly late in the 20th century, upon working-class Irish communities. Patrick Cardinal Moran (1830–1911), the Archbishop of Sydney 1884–1911, believed that Catholicism would flourish with the emergence of the new nation through Federation in 1901, provided that his people rejected "contamination" from foreign influences, such as anarchism, socialism, modernism and secularism. Moran distinguished between European socialism as an atheistic movement and those Australians calling themselves "socialists;" he approved the objectives of the latter while feeling that the European model was not a real danger in Australia. Moran's outlook reflected his whole-hearted acceptance of Australian democracy and his belief in the country as different and freer than the old societies from which its people had come.[24] Moran thus welcomed the Labor Party, and the Church stood with it in opposing conscription in the referendums of 1916 and 1917.[25] The hierarchy had close ties to Rome, which encouraged the bishops to support the British Empire and emphasise Marian piety.[26]

Culture

Australian composers who published musical works during this period include Roy Agnew, Vince Courtney, Guglielmo Enrico Lardelli, Louis Lavater and Herbert De Pinna.

First World War

Australia sent many thousands of troops to fight for Britain during the First World War between 1914 and 1918. Thousands lost their lives at Gallipoli, on the Turkish coast and many more in France. Both Australian victories and losses on World War I battlefields contribute significantly to Australia's national identity. By war's end, over 60,000 Australians had died during the conflict and 160,000 were wounded, a high proportion of the 330,000 who had fought overseas.[27]

Australia's annual holiday to remember its war dead is held on ANZAC Day, 25 April, each year, the date of the first landings at Gallipoli, in Turkey, in 1915, as part of the allied invasion that ended in military defeat. Bill Gammage has suggested that the choice of 25 April has always meant much to Australians because at Gallipoli, "the great machines of modern war were few enough to allow ordinary citizens to show what they could do." In France, between 1916 and 1918, "where almost seven times as many (Australians) died,... the guns showed cruelly, how little individuals mattered."[28]

The Sydney Morning Herald referred to the outbreak of war as Australia's "Baptism of Fire."[29] 8,141 men[30] were killed in eight months of fighting at Gallipoli, on the Turkish coast. After the Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) was withdrawn in late 1915, and enlarged to five divisions, most were moved to France to serve under British command.

The AIF's first experience of warfare on the Western Front was also the most costly single encounter in Australian military history. In July 1916, at Fromelles, in a diversionary attack during the Battle of the Somme, the AIF suffered 5,533 killed or wounded in 24 hours.[31] Sixteen months later, the five Australian divisions became the Australian Corps, first under the command of General Birdwood, and later the Australian General Sir John Monash. Two bitterly fought and divisive conscription referendums were held in Australia in 1916 and 1917. Both failed, and Australia's army remained a volunteer force. Monash's approach to the planning of military action was meticulous, and unusual for military thinkers of the time. His first operation at the relatively small Battle of Hamel demonstrated the validity of his approach and later actions before the Hindenburg Line in 1918 confirmed it.

In 1919, Prime Minister Billy Hughes and former Prime Minister Joseph Cook travelled to Paris to attend the Versailles peace conference.[32] Hughes's signing of the Treaty of Versailles on behalf of Australia was the first time Australia had signed an international treaty. Hughes demanded heavy reparations from Germany and frequently clashed with US President Woodrow Wilson. At one point Hughes declared: "I speak for 60,000 [Australian] dead".[33] He went on to ask of Wilson; "How many do you speak for?"

In 1916 the Labor Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, decided that conscription was necessary if the strength of Australia's military forces at the front was to be maintained. The Labor Party, Irish Australians, Catholics and the trade unions (heavily overlapping categories) were bitterly opposed to conscription, and Hughes and his followers were expelled from the party when they refused to back down. In 1916 and again in 1917 the voters rejected conscription in national plebiscites. (See History of Australian Conscription) Hughes united with the Liberals to form the Nationalist Party, and remained in office until 1923, when he was succeeded by Stanley Bruce. Labor remained weak and divided through the 1920s. The new Country Party took many country voters away from Labor, and in 1923 the Country Party formed a coalition government with the Nationalists.

Fisher argues that the government aggressively promoted economic, industrial, and social modernisation in the war years.[34] However, he says there was a cost in terms of a neglect in liberal-democratic values. That is, liberalism, pluralism, and respect for cultural diversity gave way to policies of exclusion and repression. He says the war turned a peaceful nation into "one that was violent, aggressive, angst- and conflict-ridden, torn apart by invisible front lines of sectarian division, ethnic conflict and socio-economic and political upheaval." The nation was fearful of enemy aliens—especially Germans, regardless of how closely they identified with Australia. The government interred 2,900 German-born men (40% of the total) and deported 700 of them after the war.[35] Irish nationalists and labour radicals were under suspicion as well. Racist hostility was high against toward nonwhites, including Pacific Islanders, Chinese and Aborigines. The result, Fischer says, was a strengthening of conformity to imperial/British loyalties and an explicit preference for immigrants from the British Isles.[34]

Paris Peace Conference, 1919

The Australian delegation, led by Prime Minister Hughes, wanted reparations, annexation of German New Guinea and rejection of the Japanese racial equality proposal. Hughes said that he had no objection to the equality proposal provided it was stated in unambiguous terms that it did not confer any right to enter Australia. Hughes was the most prominent opponent of the inclusion of the Japanese racial equality proposal, which as a result of lobbying by him and others was not included in the final Treaty, deeply offending Japan.

Hughes demanded that Australia have independent representation within the newly formed League of Nations. Hughes was concerned by the rise of Japan: within months of the declaration of the European War in 1914, Japan seized all German Pacific Island territories north of the equator. In concert with this, Australia and New Zealand occupied the German possessions south of the equator. Although Japan occupied the German territories with the blessings of the British, Hughes was alarmed by this policy.[36] At the Paris Peace Conference, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa argued their case to keep their occupied German possessions of German Samoa, German South West Africa and German New Guinea; these territories were given a "Class C Mandate" to the respective Dominions. In a same-same deal Japan obtained control over its occupied German possessions north of the equator. Hughes obtained a class C mandate for New Guinea.[37]

Wilson and Hughes had some memorable clashes, with the most famous being:

- Wilson: "But after all, you speak for only five million people."

- Hughes: "I represent sixty thousand dead."[38]

Wilson was especially offended by Australian demands and asked Hughes, whom he regarded as a "pestiferous varmint", if Australia really wanted to flout world opinion by profiting from Germany's defeat and extending its sovereignty as far north as the equator; Hughes famously replied: "That's about the size of it, Mr. President".[39]

Hughes' success in obtaining a mandate for New Guinea is regarded by many as his greatest achievement, as Japanese control might have resulted in their invasion of the Australian mainland during the Second World War.

The inter-war years

The 1920s

After the war, Prime Minister Billy Hughes led a new conservative force, the Nationalist Party, formed from the old Liberal party and breakaway elements of Labor (of which he was the most prominent), after the deep and bitter split over Conscription. An estimated 12,000 Australians died as a result of the Spanish flu pandemic of 1919, almost certainly brought home by returning soldiers.[40]

Following the success of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia the Communist Party of Australia was formed in 1920 and, though remaining electorally insignificant, it obtained some influence in the Trade Union movement and was banned during World War II for its support for the Hitler-Stalin Pact and the Menzies Government unsuccessfully tried to ban it again during the Korean War. Despite splits, the party remained active until its dissolution at the end of the Cold War.[41][42]

The Country Party (today's National Party) formed in 1920 to promulgate its version of agrarianism, which it called "Countrymindedness". The goal was to enhance the status of the graziers (operators of big sheep ranches) and small farmers, and secure subsidies for them.[43] Enduring longer than any other major party save the Labor party, it has generally operated in Coalition with the Liberal Party (since the 1940s), becoming a major party of government in Australia – particularly in Queensland.

Other significant after-effects of the war included ongoing industrial unrest, which included the 1923 Victorian Police strike.[44] Industrial disputes characterised the 1920s in Australia. Other major strikes occurred on the waterfront, in the coalmining and timber industries in the late 1920s. The union movement had established the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) in 1927 in response to the Nationalist government's efforts to change working conditions and reduce the power of the unions.

Starting on 1 February 1927 (and lasting until 12 June 1931), the Northern Territory was divided up as North Australia and Central Australia at latitude 20°S. New South Wales has had one further territory surrendered, namely Jervis Bay Territory comprising 6,677 hectares, in 1915. The external territories were added: Norfolk Island (1914); Ashmore Island, Cartier Islands (1931); the Australian Antarctic Territory transferred from Britain (1933); Heard Island, McDonald Islands, and Macquarie Island transferred to Australia from Britain (1947).

The Federal Capital Territory (FCT) was formed from New South Wales in 1911 to provide a location for the proposed new federal capital of Canberra (Melbourne was the seat of government from 1901 to 1927. The FCT was renamed the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) in 1938.) The Northern Territory was transferred from the control of the South Australian government to the Commonwealth in 1911.

Jazz music, entertainment culture, new technology and consumerism that characterised the 1920s in the USA was, to some extent, also found in Australia. Prohibition was not implemented in Australia, though anti-alcohol forces were successful in having hotels closed after 6 pm, and closed altogether in a few city suburbs.[45]

The fledgling film industry declined through the decade, over 2 million Australians attending cinemas weekly at 1250 venues. A Royal Commission in 1927 failed to assist and the industry that had begun so brightly with the release of the world's first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), atrophied until its revival in the 1970s.[46][47]

Stanley Bruce became Prime Minister in 1923, when members of the Nationalist Party Government voted to remove W.M. Hughes. Speaking in early 1925, Bruce summed up the priorities and optimism of many Australians, saying that "men, money and markets accurately defined the essential requirements of Australia" and that he was seeking such from Britain.[48] The migration campaign of the 1920s, operated by the Development and Migration Commission, brought almost 300,000 Britons to Australia,[49] although schemes to settle migrants and returned soldiers "on the land" were generally not a success. "The new irrigation areas in Western Australia and the Dawson Valley of Queensland proved disastrous".[50]

In Australia, the costs of major investment had traditionally been met by state and Federal governments and heavy borrowing from overseas was made by the governments in the 1920s. A Loan Council set up in 1928 to co-ordinate loans, three-quarters of which came from overseas.[51] Despite Imperial Preference, a balance of trade was not successfully achieved with Britain. "In the five years from 1924... to... 1928, Australia bought 43.4% of its imports from Britain and sold 38.7% of its exports. Wheat and wool made up more than two-thirds of all Australian exports," a dangerous reliance on just two export commodities.[52]

Australia embraced the new technologies of transport and communication. Coastal sailing ships were finally abandoned in favour of steam, and improvements in rail and motor transport heralded dramatic changes in work and leisure. In 1918 there were 50,000 cars and lorries in the whole of Australia. By 1929 there were 500,000.[53] The stage coach company Cobb and Co, established in 1853, finally closed in 1924.[54] In 1920, the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Service (to become the Australian airline Qantas) was established.[55] The Reverend John Flynn, founded the Royal Flying Doctor Service, the world's first air ambulance in 1928.[56] Dare devil pilot, Sir Charles Kingsford Smith pushed the new flying machines to the limit, completing a round Australia circuit in 1927 and in 1928 traversed the Pacific Ocean, via Hawaii and Fiji from the US to Australia in the aircraft Southern Cross. He went on to global fame and a series of aviation records before vanishing on a night flight to Singapore in 1935.[57]

Great Depression: the 1930s

Australia's dependence on primary exports such as wheat and wool was cruelly exposed by the Great Depression of the 1930s, which produced unemployment and destitution even greater than those seen during the 1890s. The Labor Party under James Scullin won the 1929 election in a landslide, but was quite unable to cope with the Depression. Labor split into three factions and then lost power in 1932 to a new conservative party, the United Australia Party (UAP) led by Joseph Lyons, and did not return to office until 1941. Australia made a very slow recovery from the Depression during the late 1930s. Lyons died in 1939 and was succeeded by Robert Menzies.

Exposed by continuous borrowing to fund capital works in the 1920s, the Australian and state governments were "already far from secure in 1927, when most economic indicators took a turn for the worse. Australia's dependence of exports left her extraordinarily vulnerable to world market fluctuations," according to economic historian Geoff Spenceley.[58] Debt by the state of New South Wales accounted for almost half Australia's accumulated debt by December 1927. The situation caused alarm amongst a few politicians and economists, notably Edward Shann of the University of Western Australia, but most political, union and business leaders were reluctant to admit to serious problems.[59] In 1926, Australian Finance magazine described loans as occurring with a "disconcerting frequency" unrivalled in the British Empire: "It may be a loan to pay off maturing loans or a loan to pay the interest on existing loans, or a loan to repay temporary loans from the bankers....[58] Thus, well before the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the Australian economy was already facing significant difficulties. As the economy slowed in 1927, so did manufacturing and the country slipped into recession as profits slumped and unemployment rose.[60]

At elections held in October 1929 the Labor Party was swept to power in a landslide, the former Prime Minister Stanley Bruce losing his own seat. The new Prime Minister James Scullin and his largely inexperienced Government were almost immediately faced with a series of crises. Hamstrung by their lack of control of the Senate, a lack of control over the Banking system and divisions within their Party over how best to deal with the situation, the government was forced to accept solutions that eventually split the party, as it had in 1917. Some gravitated to New South Wales Premier Lang, other to Prime Minister Scullin.

Various "plans" to resolve the crisis were suggested; Sir Otto Niemeyer, a representative of the English banks who visited in mid 1930, proposed a deflationary plan, involving cuts to government spending and wages. Treasurer Ted Theodore proposed a mildly inflationary plan, while the Labor Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang, proposed a radical plan which repudiated overseas debt.[61] The "Premier's Plan" finally accepted by federal and state governments in June 1931, followed the deflationary model advocated by Niemeyer and included a reduction of 20% in government spending, a reduction in bank interest rates and an increase in taxation.[62] In March 1931, Lang announced that interest due in London would not be paid and the Federal government stepped in to meet the debt. In May, the Government Savings Bank of New South Wales was forced to close. The Melbourne Premiers' Conference agreed to cut wages and pensions as part of a severe deflationary policy but Lang, renounced the plan. The grand opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 provided little respite to the growing crisis straining the young federation. With multimillion-pound debts mounting, public demonstrations and move and counter-move by Lang and the Scullin, then Lyons federal governments, the Governor of New South Wales, Philip Game, had been examining Lang's instruction not to pay money into the Federal Treasury. Game judged it was illegal. Lang refused to withdraw his order and, on 13 May, he was dismissed by Governor Game. At June elections, Lang Labor's seats collapsed.[63]

May 1931 had seen the creation of a new conservative political force, the United Australia Party formed by breakaway members of the Labor Party combining with the Nationalist Party. At Federal elections in December 1931, the United Australia Party, led by former Labor member Joseph Lyons, easily won office. They remained in power under Lyons through Australia's recovery from the Great Depression and into the early stages of the World War II under Robert Menzies.

Lyons favoured the tough economic measures of the "Premiers' Plan", pursued an orthodox fiscal policy and refused to accept NSW Premier Jack Lang's proposals to default on overseas debt repayments. According to author Anne Henderson of the Sydney Institute, Lyons held a steadfast belief in the need to balance budgets, lower costs to business and restore confidence and the Lyons period gave Australia stability and eventual growth between the drama of the Depression and the outbreak of the Second World War. A lowering of wages was enforced and industry tariff protections maintained, which together with cheaper raw materials during the 1930s saw a shift from agriculture to manufacturing as the chief employer of the Australian economy – a shift which was consolidated by increased investment by the commonwealth government into defence and armaments manufacture. Lyons saw restoration of Australia's exports as the key to economic recovery.[64] The Lyons government has often been credited with steering recovery from the depression, although just how much of this was owed to their policies remains contentious.[62] Stuart Macintyre also points out that although Australian GDP grew from £386.9 million to £485.9 million between 1931–1932 and 1938–1939, real domestic product per head of population was still "but a few shillings greater in 1938–1939 (£70.12), than it had been in 1920–1921 (£70.04).[65]

There is debate over the extent reached by unemployment in Australia, often cited as peaking at 29% in 1932. "Trade Union figures are the most often quoted, but the people who were there…regard the figures as wildly understating the extent of unemployment" wrote historian Wendy Lowenstein in her collection of oral histories of the Depression.[66] However, David Potts argues that "over the last thirty years …historians of the period have either uncritically accepted that figure (29% in the peak year 1932) including rounding it up to 'a third,' or they have passionately argued that a third is far too low."[67] Potts suggests a peak national figure of 25% unemployed.[68]

Extraordinary sporting successes did something to alleviate the spirits of Australians during the economic downturn. In a Sheffield Shield cricket match at the Sydney Cricket Ground in 1930, Don Bradman, a young New South Welshman of just 21 years of age wrote his name into the record books by smashing the previous highest batting score in first-class cricket with 452 runs not out in just 415 minutes.[69] The rising star's world beating cricketing exploits were to provide much needed joy to Australians through the emerging Great Depression in Australia and post-World War II recovery. Between 1929 and 1931 the racehorse Phar Lap dominated Australia's racing industry, at one stage winning fourteen races in a row.[70] Famous victories included the 1930 Melbourne Cup, following an assassination attempt and carrying 9 stone 12 pounds weight.[71] Phar Lap sailed for the United States in 1931, going on to win North America's richest race, the Agua Caliente Handicap in 1932. Soon after, on the cusp of US success, Phar Lap developed suspicious symptoms and died. Theories swirled that the champion race horse had been poisoned and a devoted Australian public went into shock.[72] The 1938 British Empire Games were held in Sydney from 5–12 February, timed to coincide with Sydney's sesqui-centenary (150 years since the foundation of British settlement in Australia).

Second World War

.jpg.webp)

Defence policy in the 1930s

Defence issues became increasingly prominent in public affairs with the rise of fascism in Europe and militant Japan in Asia.[73] Prime Minister Lyons sent veteran World War I Prime Minister Billy Hughes to represent Australia at the 1932 League of Nations Assembly in Geneva and in 1934 Hughes became Minister for Health and Repatriation. Later Lyons appointed him Minister for External Affairs, however Hughes was forced to resign in 1935 after his book Australia and the War Today exposed a lack of preparation in Australia for what Hughes correctly supposed to be a coming war. Soon after, the Lyons government tripled the defence budget.[74] With Western Powers developing a policy of appeasement to try to satisfy the demands of Europe's new dictators without war, Prime Minister Lyons sailed for Britain in 1937 for the coronation of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, en route conducting a diplomatic mission to Italy on behalf of the British Government, visiting Benito Mussolini with assurances of British friendship.[74]

Until the late 1930s, defence was not a significant issue for Australians. At the 1937 elections, both political parties advocated increased defence spending, in the context of increased Japanese aggression in China and Germany's aggression in Europe. There was a difference in opinion over how the defence spending should be allocated however. The UAP government emphasised co-operation with Britain in "a policy of imperial defence." The lynchpin of this was the British naval base at Singapore and the Royal Navy battle fleet "which, it was hoped, would use it in time of need."[75] Defence spending in the inter-war years reflected this priority. In the period 1921–1936 totalled £40 million on the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), £20 million on the Australian Army and £6 million on the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) (established in 1921, the "youngest" of the three services). In 1939, the Navy, which included two heavy cruisers and four light cruisers, was the service best equipped for war.[76]

Scarred by the experiences of World War I, Australia reluctantly prepared for a new war, in which the primacy of the British Royal Navy would indeed prove insufficient to defend Australia from attack from the north. Billy Hughes was brought back into cabinet by Lyons as Minister for External Affairs in 1937.[74] From 1938, Lyons used Hughes to head a recruitment drive for the Australian Defence Force.[64] Prime Minister Lyons died in office in April 1939, with Australia just months from war, and the United Australia Party selected Robert Menzies as its new leader. Fearing Japanese intentions in the Pacific, Menzies established independent embassies in Tokyo and Washington to receive independent advice about developments.[77]

Gavin Long argues that the Labor opposition urged greater national self-reliance through a buildup of manufacturing and more emphasis on the Army and RAAF, as Chief of the General Staff, John Lavarack also advocated.[78] In November 1936, Labor leader John Curtin said "The dependence of Australia upon the competence, let alone the readiness, of British statesmen to send forces to our aid is too dangerous a hazard upon which to found Australia's defence policy.".[75] According to John Robertson, "some British leaders had also realised that their country could not fight Japan and Germany at the same time." But "this was never discussed candidly at…meeting(s) of Australian and British defence planners", such as the 1937 Imperial Conference.[79]

By September 1939 the Australian Army numbered 3,000 regulars.[80] A recruiting campaign in late 1938, led by Major-General Thomas Blamey increased the reserve militia to almost 80,000.[81] The first division raised for war was designated the 6th Division, of the 2nd AIF, there being five Militia Divisions on paper and a 1st AIF in the First World War.[82]

War

On 3 September 1939, the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, made a national radio broadcast:

My fellow Australians. It is my melancholy duty to inform you, officially, that, in consequence of the persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her, and that, as a result, Australia is also at war.[4]

Thus began Australia's involvement in the six-year global conflict. Australians were to fight in an extraordinary variety of locations, from withstanding the advance of Hitler's Panzers in the Siege of Tobruk; to turning back the advance of the Imperial Japanese Army in the New Guinea Campaign. From bomber missions over Europe and Mediterranean naval engagements, to facing Japanese mini-sub raids on Sydney Harbour and devastating air raids on the city of Darwin.

.jpg.webp)

The recruitment of a volunteer military force for service at home and abroad was announced, the 2nd Australian Imperial Force, and a citizen militia organised for local defence. Troubled by Britain's failure to increase defences at Singapore, Menzies was cautious in committing troops to Europe. By the end of June 1940, France, Norway and the Low Countries had fallen to Nazi Germany and Britain, stood alone with its Dominions. Menzies called for "all out war", increasing Federal powers and introducing conscription. Menzies' minority government came to rely on just two independents after the 1940 election

In January 1941, Menzies flew to Britain to discuss the weakness of Singapore's defences. Arriving in London during The Blitz, Menzies was invited into Winston Churchill's British War Cabinet for the duration of his visit. Returning to Australia, with the threat of Japan imminent and with the Australian army suffering badly in the Greek and Crete campaigns, Menzies re-approached the Labor Party to form a War Cabinet. Unable to secure their support, and with an unworkable parliamentary majority, Menzies resigned as Prime Minister. The Coalition held office for another month, before the independents switched allegiance and John Curtin was sworn in Prime Minister.[77] Eight weeks later, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

From 1940 to 1941, Australian forces played prominent roles in the fighting in the Mediterranean theatre, including Operation Compass, the Siege of Tobruk, the Greek campaign, the Battle of Crete, the Syria-Lebanon campaign and the Second Battle of El Alamein.

A garrison of around 14,000 Australian soldiers, commanded by Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead was besieged in Tobruk, Libya by the German-Italian army of General Erwin Rommel between April and August 1941. The Nazi propagandist Lord Haw Haw derided the defenders as 'rats', a term the soldiers adopted as an ironic compliment: "The Rats of Tobruk". Vital in the defence of Egypt and the Suez Canal, the Siege saw the advance of the German army halted for the first time and provided a morale boost for the British Commonwealth, which was then standing alone against Hitler.[83]

With most of Australia's best forces committed to fight against Hitler in the Middle East, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US naval base in Hawaii, on 8 December 1941 (eastern Australia time). The British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and battlecruiser HMS Repulse sent to defend Singapore were sunk soon afterwards. Australia was ill-prepared for an attack, lacking armaments, modern fighter aircraft, heavy bombers, and aircraft carriers. While demanding reinforcements from Churchill, on 27 December 1941 Curtin published an historic announcement:[84]

"The Australian Government... regards the Pacific struggle as primarily one in which the United States and Australia must have the fullest say in the direction of the democracies' fighting plan. Without inhibitions of any kind, I make it clear that Australia looks to America, free of any pangs as to our traditional links or kinship with the United Kingdom."[85]

British Malaya quickly collapsed, shocking the Australian nation. British, Indian and Australian troops made a disorganised last stand at Singapore, before surrendering on 15 February 1942. 15,000 Australian soldiers became prisoners of war. Curtin predicted that the 'battle for Australia' would now follow. On 19 February, Darwin suffered a devastating air raid, the first time the Australian mainland had ever been attacked by enemy forces. Over the following 19 months, Australia was attacked from the air almost 100 times.

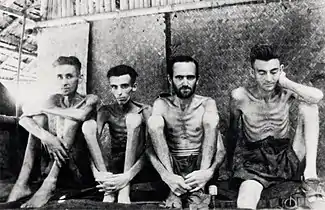

Three reinforced infantry battalions awaited the advancing Japanese in an arc across Australia's north: Sparrow Force on Timor, Gull Force on Ambon and Lark Force on New Britain.[86] These "bird forces" were overwhelmed: in early 1942, Lark Force was defeated in the Battle of Rabaul (1942) and Gull Force surrendered in the Battle of Ambon and through 1942–3, Sparrow Force engaged in a prolonged guerilla campaign in Battle of Timor. Captured Australian Prisoners of War suffered severe ill-treatment in the Pacific Theatre. Around 160 men of Lark Force were bayonetted after capture at Toll Plantation, while 300 of the surrendering Gull Force were summarily executed in the Laha Massacre and 75% of their comrades perished due to ill-treatment and the conditions of their incarceration.[87][88] In 1943, 2,815 Australian POWs died constructing Japan's Burma-Thailand Railway[89] In 1944, the Japanese inflicted the Sandakan Death March on 2,000 Australian and British prisoners of war – only six survived. This was the single worst war crime perpetrated against Australians in war.[90]

Two battle hardened Australian divisions were already steaming from the Mid-East for Singapore. Churchill wanted them diverted to Burma, but Curtin refused, and anxiously awaited their return to Australia. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered his commander in the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur, to formulate a Pacific defence plan with Australia in March 1942. Curtin agreed to place Australian forces under the command of General MacArthur, who became "Supreme Commander of the South West Pacific". Curtin had thus presided over a fundamental shift in Australia's foreign policy. MacArthur moved his headquarters to Melbourne in March 1942 and American troops began massing in Australia. In late May 1942, Japanese midget submarines sank an accommodation vessel in a daring raid on Sydney Harbour. On 8 June 1942, two Japanese submarines briefly shelled Sydney's eastern suburbs and the city of Newcastle.[91]

.png.webp)

In an effort to isolate Australia, the Japanese planned a seaborne invasion of Port Moresby, in the Australian Territory of New Guinea. In May 1942, the US Navy engaged the Japanese in the Battle of the Coral Sea and halted the attack. The Battle of Midway in June effectively defeated the Japanese navy and the Japanese army launched a land assault on Moresby from the north.[84] Between July and November 1942, Australian forces repulsed Japanese attempts on the city by way of the Kokoda Track, in the highlands of New Guinea. The Battle of Milne Bay in August 1942 was the first Allied defeat of Japanese land forces.

Meanwhile, in North Africa, the Axis Powers had driven Allies back into Egypt. A turning point came between July and November 1942, when Australia's 9th Division played a crucial role in some of the heaviest fighting of the First and Second Battle of El Alamein, which turned the North Africa Campaign in favour of the Allies.[92]

Concerned to maintain British commitment to the defence of Australia, Prime Minister Curtin announced in November 1943 that Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester was to be appointed Governor General of Australia. The brother of King George VI arrived in Australia to take up his post in January 1945. Curtin hoped this might influence the British to despatch men and equipment to the Pacific, and the appointment reaffirmed the important role of the Crown to the Australian nation.[93]

On 14 May 1943, the Australian Hospital Ship Centaur, though clearly marked as a medical vessel, was sunk by a Japanese submarine off the Queensland coast. Of the 332 persons on board including doctors and nurses, just 64 survived and only one of the ship's nursing staff, Ellen Savage. The war crime further enraged popular opinion against Japan.[94][95]

The Battle of Buna-Gona between November 1942 and January 1943, saw Australian and United States forces attack the main Japanese beachheads in New Guinea, at Buna, Sanananda and Gona. Facing tropical disease, difficult terrain and well constructed Japanese defences, the allies only secured victory with heavy casualties.[96] The battle set the tone for the remainder of the New Guinea Campaign. The offensives in Papua and New Guinea of 1943–44 were the single largest series of connected operations ever mounted by the Australian armed forces.[97] The Supreme Commander of operations was the United States General Douglas Macarthur, with Australian General Thomas Blamey taking a direct role in planning and operations being essentially directed by staff at New Guinea Force headquarters in Port Moresby.[97] Bitter fighting continued in New Guinea between the largely Australian force and the Japanese 18th Army based in New Guinea until the Japanese surrender in 1945.

MacCarthur excluded Australian forces from the main push north into the Philippines and Japan. It was left to Australia to lead amphibious assaults against Japanese bases in Borneo. Curtin suffered from ill health from the strains of office and died weeks before the war ended, replaced by Ben Chifley.

Of Australia's wartime population of 7 million, almost 1 million men and women served in a branch of the services during the six years of warfare. By war's end, gross enlistments totalled 727,200 men and women in the Australian Army (of whom 557,800 served overseas), 216,900 in the RAAF and 48,900 in the RAN. Over 39,700 were killed or died as prisoners of war, about 8,000 of whom died as prisoners of the Japanese.[98][99]

The Homefront

The Australian economy was markedly affected by World War II.[100] Expenditure on war reached 37% of GDP by 1943–4, compared to 4% expenditure in 1939–1940.[101] Total war expenditure was £2,949 million between 1939 and 1945.[102]

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Although the peak of Army enlistments occurred in June–July 1940, when over 70,000 enlisted, it was the Curtin Labor government, formed in October 1941, that was largely responsible for "a complete revision of the whole Australian economic, domestic and industrial life."[103] Rationing of fuel, clothing and some food was introduced, (although less severely than in Britain) Christmas holidays curtailed, "brown outs" introduced and some public transport reduced. From December 1941, the Government evacuated all women and children from Darwin and northern Australia, and over 10,000 refugees arrived from South East Asia as Japan advanced.[104] In January 1942, the Manpower Directorate was set up "to ensure the organisation of Australians in the best possible way to meet all defence requirements."[103] Minister for War Organisation of Industry, John Dedman introduced a degree of austerity and government control previously unknown, to such an extent that he was nicknamed "the man who killed Father Christmas."

In May 1942 uniform tax laws were introduced in Australia, as state governments relinquished their control over income taxation, "The significance of this decision was greater than any other… made throughout the war, as it added extensive powers to the Federal Government and greatly reduced the financial autonomy of the states."[105]

Manufacturing grew significantly because of the war. "In 1939 there were only three Australian firms producing machine tools, but by 1943 there were more than one hundred doing so."[106] From having few front line aircraft in 1939, the RAAF had become the fourth largest allied Air Force by 1945. A number of aircraft were built under licence in Australia before the war's end, notably the Beaufort and Beaufighter, although the majority of aircraft were from Britain and later, the USA.[107] The Boomerang fighter, designed and built in four months of 1942, emphasised the desperate state Australia found itself in as the Japanese advanced.

Australia also created, virtually from nothing, a significant female workforce engaged in direct war production. Between 1939 and 1944 the number of women working in factories rose from 171,000 to 286,000.[108] Dame Enid Lyons, widow of former Prime Minister Joseph Lyons, became the first woman elected to the House of Representatives in 1943, joining the Robert Menzies' new centre-right Liberal Party of Australia, formed in 1945. At the same election, Dorothy Tangney became the first woman elected to the Senate.

Australian trade unions support of the war, after Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941. However, in spring 1940, the coal miners struck for higher wages for 67 days under communist leadership.[109]

The steps to full sovereignty

Australia achieved full sovereignty from the UK on a progressive basis.[110] On 1 January 1901, the British Parliament passed legislation allowing the six Australian colonies to govern in their own right as part of the Commonwealth of Australia. This achieved federation of the colonies after a decade of planning, consultation and voting.[111] The Commonwealth of Australia was now a dominion of the British Empire.[112]

The Federal Capital Territory (later renamed the Australian Capital Territory) was formed in 1911 as the location for the future federal capital of Canberra. Melbourne was the temporary seat of government from 1901 to 1927 while Canberra was being constructed.[113] The Northern Territory was transferred from the control of the South Australian government to the federal parliament in 1911.[114]

In 1931, the Parliament of Britain passed the Statute of Westminster which prevented Britain from making laws for its dominions. After it was ratified by the Parliament of Australia, this formally ended most of the constitutional links between Australia and the UK, although Australia's States remained "self-governing colonial dependencies of the British Crown".[115]

The statute formalised the Balfour Declaration of 1926, a report resulting from the 1926 Imperial Conference of British Empire leaders in London, which had defined Dominions of the British empire in the following way:

They are autonomous Communities within the British Empire, equal in status, in no way subordinate one to another in any aspect of their domestic or external affairs, though united by a common allegiance to the Crown, and freely associated as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.[116][117]

Australia did not ratify the Statute of Westminster 1931 until over a decade later, with the Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942. However, the ratification was backdated to 1939 to confirm the validity of legislation passed by the Australian Parliament during World War II.[118][119] According to historian Frank Crowley, this was because Australians had little interest in redefining their relationship with Britain until the crisis of World War II.[120]

The final step to full sovereignty was the passing of the Australia Act 1986 in the UK. The Act removed the right of the British Parliament to make laws for Australia and ended any British role in the government of the Australian States.[115] It also removed the right of appeal from Australian courts to the British Privy Council in London. Most important, the Act transferred into Australian hands full control of all Australia's constitutional documents.[121]

See also

References

- 1 2 Bean, C.E.W. (2014) [1946]. ANZAC to Amiens (Revised ed.). Melbourne: Penguin Books. p. 5.

- 1 2 Norris, R. "Deakin, Alfred (1856–1919)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ However it was not until the 1960s that this occurred.

- 1 2 Crowley (1973a), p. 1.

- ↑ Macintyre (1986), p. 86.

- ↑ "We believe: the Liberal party and the liberal cause". The Australian. 26 October 2009.

- ↑ Aitkin, Don (1972). The Country Party in New South Wales: A Study of Organisation and Survival. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

- ↑ Graham, B.D. (1959). "Graziers in Politics, 1917 to 1929". Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand. 8 (32): 383–391. doi:10.1080/10314615908595138.

- ↑ Crowley (1973a), p. 13.

- ↑ Gibb (1973), p. 113.

- ↑ Gibb (1973), p. 112.

- ↑ Cahill, A. E. "Moran, Patrick Francis (1830–1911)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ Macintyre (1986), p. 310.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Carolyn. "Kisch, Egon Erwin (1885–1948)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ Crowley (1973a), p. 22.

- 1 2 Gammage (1988), p. 157.

- ↑ McQueen, Humphrey (1986). Social Sketches of Australia 1888–1975. Melbourne: Penguin Books. p. 42. ISBN 0-14-004435-3.

- ↑ Macintyre (1986), p. 198.

- ↑ Macintyre (1986), p. 199.

- ↑ Hilliard, David (February 1986). "The Transformation of South Australian Anglicanism, c.1880–1930". Journal of Religious History. 14 (1): 38–56. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1986.tb00454.x.

- ↑ Withycombe, Robert (June 1990). "The Anglican Episcopate in England and Australia in the Early Twentieth Century: Towards a Comparative Study". Journal of Religious History. 16 (2): 154–172. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1990.tb00657.x.

- ↑ Mansfield, Joan (June 1985). "The Social Gospel and the Church of England in New South Wales in the 1930s". Journal of Religious History. 13 (4): 411–433. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1985.tb00446.x.

- ↑ Uidam, C. (June 1985). "Why the Church Union Movement Failed in Australia, 1901–1925". Journal of Religious History. 13 (4): 393–411. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1985.tb00445.x.

- ↑ Cahill, A.E. (June 1960). "Catholicism and Socialism: The 1905 Controversy in Australia". Journal of Religious History. 1 (2): 88–101. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.1960.tb00017.x.

- ↑ Hearn, Mark (March 2001). "Containing 'Contamination': Cardinal Moran and Fin de Siècle Australian National Identity, 1888–1911". Journal of Religious History. 34 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9809.2009.00828.x.

- ↑ O'Farrell, Patrick (1992) [1977]. The Catholic Church and community: an Australian history (3rd revised ed.). Kensington, NSW: New South Wales University Press.

- ↑ "First World War 1914–18". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Gammage (1988), p. 166.

- ↑ Gammage (1988), p. 159.

- ↑ "Gallipoli". Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ Gammage, Bill (1974). The Broken Years. Penguin Australia. pp. 158–162. ISBN 0-14-003383-1.

- ↑ Fitzhardinge, L. F. "Hughes, William Morris (Billy) (1862–1952)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ Lowe (1995), p. 132.

- 1 2 Fischer, Gerhard (April 1995). "'Negative integration' and an Australian road to modernity: Interpreting the Australian homefront experience in World War I". Australian Historical Studies. 26 (104): 452–476. doi:10.1080/10314619508595974.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst & Macintyre (2001), pp. 283–284.

- ↑ Lowe (1995), p. 129.

- ↑ Louis, Wm. Roger (1966). "Australia and the German Colonies in the Pacific, 1914–1919". Journal of Modern History. 38 (4): 407–421. doi:10.1086/239953. JSTOR 1876683. S2CID 143884972.

- ↑ MacCallum, Mungo (2013). The Good, the Bad and the Unlikely: Australia's Prime Ministers. Black Inc. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-863955874.

- ↑ Maloney, Shane (2011). Australian Encounters. Black Inc. pp. 42–44. ISBN 978-1-863955393.

- ↑ Bassett (1986), p. 236.

- ↑ Murray, Robert. "Thornton, Ernest (1907–1969)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ "Australian Communist Party - political party, Australia". britannica.com.

- ↑ Wear, Rae (1990). "Countrymindedness Revisited". Australian Political Science Association. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011.

- ↑ Robson (1980), p. 18.

- ↑ Robson (1980), p. 45.

- ↑ Robson (1980), p. 48.

- ↑ Reade, Eric (1979). History and Heartburn; The Saga of Australian Film 1896–1978. Sydney: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-312033-X.

- ↑ Robson (1980), p. 76.

- ↑ Macintyre (1986), pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Castle (1982), p. 285.

- ↑ Castle (1982), p. 253.

- ↑ Macintyre (1986), p. 204.

- ↑ Castle (1982), p. 273.

- ↑ Bassett (1986), pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Bassett (1986), p. 213.

- ↑ Bucknall, Graeme. "Flynn, John (1880–1951)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ Howard, Frederick. "Kingsford Smith, Sir Charles Edward (1897–1935)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- 1 2 Spenceley (1981), p. 14.

- ↑ Spenceley (1981), pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Pook, Henry (1993). Windows on our Past; Constructing Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 195. ISBN 0-19-553544-8.

- ↑ Bassett (1986), pp. 118–119.

- 1 2 Close (1982), p. 318.

- ↑ Nairn, Bede. "Lang, John Thomas (Jack) (1876–1975)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- 1 2 Henderson, Anne (2011). Joseph Lyons: The People's Prime Minister. Kingsford, NSW: University of New South Wales Press.

- ↑ Macintyre (1986), p. 287.

- ↑ Lowenstein, Wendy (1978). Weevils in the Flour: an oral record of the 1930s depression in Australia. Fitzroy, Vic.: Scribe Publications. p. 14. ISBN 0-908011-06-7.

- ↑ Potts, David (1991). "A Reassessment of the extent of Unemployment in Australia during the Great Depression". Australian Historical Studies. 24 (7): 378–398. doi:10.1080/10314619108595855.

- ↑ Potts, David (2006). The Myth of the Great Depression. Carlton North: Scribe Press. p. 395. ISBN 1-920769-84-6.

- ↑ "Don Bradman". Australia's Culture Portal. Archived from the original on 8 April 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2011.

- ↑ "Phar Lap - Winner". Museum Victoria. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008.

- ↑ "Phar Lap - 1930 Melbourne Cup". Museum Victoria. Archived from the original on 15 May 2008.

- ↑ "Phar Lap's Death". Museum Victoria. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008.

- ↑ "In office - Joseph Lyons (6 January 1932 – 7 April 1939) and Enid Lyons". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 Carroll, Brian (1978). From Barton to Fraser: Every Australian Prime Minister. Stanmore, NSW: Cassell Australia.

- 1 2 Robertson (1984), p. 12.

- ↑ Department of Defence (Navy) (1976). An Outline of Australian Naval History. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. p. 33. ISBN 0-642-02255-0.

- 1 2 "Robert Menzies, Prime Minister 1939–41". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- ↑ Long (1952), pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Robertson, John (1988). "The Distant War: Australia and Imperial defence 1919-1914". In McKernan, M. & Browne, M. (eds.). Australia: Two Centuries of War and Peace. Canberra: Australian War Memorial and Allen & Unwin Australia. p. 225. ISBN 0-642-99502-8.

- ↑ Robertson (1984), p. 17.

- ↑ Long (1952), p. 26.

- ↑ Robertson (1984), p. 20: "Thus Australian battalions of World War II carried the prefix 2/ to distinguish them from battalions of World War I".

- ↑ "Siege of Tobruk". Australian War Memorial.

- 1 2 "In office - John Curtin (7 October 1941 – 5 July 1945) and Elsie Curtin". National Archives of Australia. Archived from the original on 17 January 2012.

- ↑ Crowley (1973b), p. 51.

- ↑ "Bird Forces". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ↑ "2/22nd Battalion". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- ↑ "Laha Massacre". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012.

- ↑ "Stolen Years: Australian prisoners of war - the Burma–Thailand Railway". Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ "Stolen Years: Australian prisoners of war - Sandakan". Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ Dunn, Peter (25 December 2006). "Midget Submarine Attack on Sydney Harbour". Australia At War. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "El Alamein". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008.

- ↑ Cunneen, Chris. "Gloucester, first Duke of (1900–1974)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University – via Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- ↑ James, Karl (14 May 2008). "The Sinking of the Centaur". Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ "Centaur (Hospital ship)". Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ "Battle of Buna". Australian War Memorial. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

- 1 2 Stanley, Peter. "Wartime Issue 23 - New Guinea Offensive". Australian War Memorial.

- ↑ Bassett (1986), pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Long, Gavin (1963). Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1. Army, Volume 7: The Final Campaigns. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. pp. 622–637.

- ↑ Close (1982), p. 209.

- ↑ Robertson (1984), p. 198.

- ↑ Long, Gavin (1973). The Six Years War: A Concise History of Australia in the 1939–1945 War. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. p. 474. ISBN 0-642-99375-0.

- 1 2 Robertson (1984), p. 195.

- ↑ Robertson (1984), pp. 202–203.

- ↑ Crowley (1973a), p. 55.

- ↑ Close (1982), p. 210.

- ↑ Robertson (1984), pp. 189–190.

- ↑ Close (1982), p. 211.

- ↑ Crowley (1973b), pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Donovan, David (6 December 2010). "Australia's last brick of nationhood". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

Many people incorrectly assume that Australia became a fully independent and sovereign nation on January 1st, 1901 with Federation.

- ↑ Davison, Hirst & Macintyre (2001), pp. 243–244.

- ↑ "History of the Commonwealth". Commonwealth of Nations. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ Otto, Kristin (25 June 2007). "When Melbourne was Australia's capital city". The University of Melbourne Voice. 1 (8). Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2010 – via University of Melbourne.

- ↑ Official year book of the Commonwealth of Australia. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1957.

- 1 2 Twomey, Anne (May 2007). "The De-Colonisation of the Australian States, Paper No. 07/19". Sydney Law School Research Paper. SSRN 984994 – via SSRN.

...Statute of Westminster 1931, the Australian States remained 'self-governing colonial dependencies of the British Crown' until the Australia Acts 1986 came into force.

- ↑ Bassett (1986), p. 271.

- ↑ It has also been argued that the signing of the Treaty of Versailles by Australia shows de facto recognition of sovereign nation status. See Sir Geoffrey Butler KBE, MA and Fellow, Librarian and Lecturer in International Law and Diplomacy of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge author of "A Handbook to the League of Nations.

- ↑ "Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942 (Cth)". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- ↑ "Statute of Westminster Adoption Act 1942" (PDF). ComLaw. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ↑ Crowley (1973a), p. 417.

- ↑ "Australia Act 1986". Australasian Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 4 January 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

Bibliography

- Bassett, Jan, ed. (1986). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554422-6.

- Castle, Josie (1982). "The 1920s". In Willis, Ray; et al. (eds.). Issues in Australian History. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. ISBN 978-0-582663275.

- Close, John (1982). "Australians in Wartime". In Willis, Ray; et al. (eds.). Issues in Australian History. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. ISBN 978-0-582663275.

- Crowley, Frank (1973a). Modern Australia in Documents: Volume 1 - 1901–1939. Melbourne: Wren Publishing. ISBN 0-85885-032-X.

- Crowley, Frank (1973b). Modern Australia in Documents: Volume 2 - 1939-1970. Melbourne: Wren Publishing. ISBN 0-85885-032-X.

- Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John & Macintyre, Stuart, eds. (2001). The Oxford Companion to Australian History (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Gammage, Bill (1988). "The Crucible: The Establishment of the Anzac Tradition 1899–1918". In McKernan, M. & Browne, M. (eds.). Australia: Two Centuries of War and Peace. Canberra: Australian War Memorial and Allen & Unwin Australia. ISBN 0-642-99502-8.

- Gibb, D.M. (1973). The Making of White Australia. Melbourne: Victorian Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-950096759.

- Long, Gavin (1952). Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1. Army, Volume 1: To Benghazi. Canberra: Australian War Memorial.

- Lowe, David (1995). "Australia in the World". In Beaumont, Joan (ed.). Australia's War, 1914–18. Allen & Unwin.

- Macintyre, Stuart (1986). The Oxford History of Australia: Volume 4: 1901-42, the Succeeding Age. Oxford University Press.

- Robertson, John (1984). Australia Goes To War, 1939–1945. Sydney: Doubleday. ISBN 0-86824-155-5.

- Robson, Lloyd (1980). Australia in the Nineteen Twenties: Commentary and Documents. Melbourne: Nelson Publishers. ISBN 978-0-170059022.

- Spenceley, Geoff (1981). The Depression Decade. Melbourne: Thomas Nelson. ISBN 0-17-006048-9.

Further reading

- Bramble, Tom (2008). Trade Unionism in Australia: A History from Flood to Ebb Tide. ISBN 978-0521888035.

- Bridge, Carl, ed. (1991). Munich to Vietnam: Australia's Relations with Britain and the United States since the 1930s. Melbourne University Press.

- Casey, R. G. (September 1937). "Australia in World Affairs". International Affairs. 16 (5): 698–713. doi:10.2307/2603816. JSTOR 2603816.

- Day, David (1992). Reluctant Nation: Australia and the Allied Defeat of Japan 1942–45.

- Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan & Prior, Robin (1996). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History.

- Edwards, John (2005). Curtin's Gift: Reinterpreting Australia's Greatest Prime Minister.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, (12th ed. 1922) comprises the 11th edition plus three new volumes 30–31–32 that cover events since 1911 with very thorough coverage of the war as well as every country and colony. Included also in 13th edition (1926) partly online.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1922). Full text of vol 30 ABBE to ENGLISH HISTORY. online free; the "Australia" article is vol 30 pp. 304–312.

- Hearn, Mark; Knowles, Harry & Cambridge, Ian (1998). One Big Union: A History of the Australian Workers Union 1886–1994.

- Jupp, James, ed. (2002). The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, its People and their Origins (2nd ed.).

- McDonald, John (2002). Federation: Australian Art and Society, 1901–2001. National Gallery of Australia.

- McLean, Ian W. (1999). "Consumer Prices and Expenditure Patterns in Australia 1850–1914". Australian Economic History Review. 39 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1111/1467-8446.00036. ISSN 0004-8992. Includes a consumer price index (CPI) for the period 1850 to 1914.

- Samuels, Selina, ed. (2002). Australian Writers, 1915–50.

- Ward, Russell (1977). A Nation for a Continent: The History of Australia, 1901–1975.

- Ward, Smart (2001). Australia and the British Embrace: The Demise of the Imperial Ideal.

- Watt, Alan (1967). The Evolution of Australian Foreign Policy 1938–1965. Cambridge University Press.

- Welsh, Frank (2008). Australia: A New History of the Great Southern Land.

Primary sources

- Kemp, Rod & Stanton, Marion, eds. (2004). Speaking for Australia: Parliamentary Speeches That Shaped Our Nation. Allen & Unwin.