| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

The prehistory of Australia is the period between the first human habitation of the Australian continent and the colonisation of Australia in 1788, which marks the start of consistent written documentation of Australia. This period has been variously estimated, with most evidence suggesting that it goes back between 50,000 and 65,000 years. This era is referred as prehistory rather than history because knowledge of this time period does not derive from written documentation. However, some argue that Indigenous oral tradition should be accorded an equal status.[1]

The nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle is no longer considered the dominant nutritional style prior to colonisation, there is extensive evidence of land management by practices such as complex gardening, cultural burning,[2][3] and in some areas, agriculture,[4][5][6] fish farming,[7][8] and permanent settlements.[9][10][11][12]

Arrival

The earliest evidence of humans in Australia has been variously estimated, with most agreement as of 2018 that it dates from between 50,000 and 65,000 years BP.[13][14]

There is considerable discussion among archaeologists as to the route taken by the first migrants to Australia, widely taken to be ancestors of the modern Aboriginal peoples. Migration took place during the closing stages of the Pleistocene, when sea levels were much lower than they are today. Repeated episodes of extended glaciation during the Pleistocene epoch resulted in decreases of sea levels by more than 100 metres in Australasia.[15] People appear to have arrived by sea during a period of glaciation, when New Guinea and Tasmania were joined to the continent of Australia. The continental coastline extended much further out into the Timor Sea, and Australia and New Guinea formed a single landmass (known as Sahul), connected by an extensive land bridge across the Arafura Sea, Gulf of Carpentaria and Torres Strait. Nevertheless, the sea still presented a major obstacle so it is theorised that these ancestral people reached Australia by island hopping.[15] Two routes have been proposed. One follows an island chain between Sulawesi and New Guinea and the other reaches North Western Australia via Timor.[16] Rupert Gerritsen has suggested an alternative theory, involving accidental colonisation as a result of tsunamis.[17] The journey still required sea travel however, making them some of the world's earliest mariners.[18]

In the 2013 book First Footprints: The Epic Story of the First Australians, Scott Cane writes that the first wave may have been prompted by the eruption of Toba, and if they arrived around 70,000 years ago, they could have crossed the water from Timor, when the sea level was low – but if they came later, around 50,000 years ago, a more likely route would be through the Moluccas to New Guinea. Given that the likely landfall regions have been under around 50 metres of water for the last 15,000 years, it is unlikely that the timing will ever be established with certainty.[19]

Dating of sites

The minimum widely accepted time frame for the arrival of humans in Australia is placed at least 48,000 years ago.[20] Many sites dating from this time period have been excavated. In Arnhem Land Madjedbebe (formerly known as Malakunanja II) fossils and a rock shelter have been dated to around 65,000 years old.[14][21] According to mitochondrial DNA research, Aboriginal people reached Eyre Peninsula (South Australia) 49,000-45,000 years ago from both the east (clockwise, along the coast, from northern Australia) and the west (anti-clockwise).[22]: 189

Radiocarbon dating suggests that they lived in and around Sydney for at least 30,000 years.[23] In an archaeological dig in Parramatta, Western Sydney, it was found that some Aboriginal peoples used charcoal, stone tools and possible ancient campfires.[24] Near Penrith, a far western suburb of Sydney, numerous Aboriginal stone tools were found in Cranebrook Terraces gravel sediments having dates of 45,000 to 50,000 years BP. This would mean that there was human settlement in Sydney earlier than thought.[25]

Archaeological evidence indicates human habitation at the upper Swan River, Western Australia by about 40,000 years ago.[26] in 1999 Charles Dortch identified chert and calcrete flake stone tools, found at Rottnest Island in Western Australia, as possibly dating to at least 70,000 years ago.[27][28] This seems to tie in accurately with U/Th and 14C results of a flint tool found embedded in Tamala limestone (Aminozone C)[29] as well as both mtDNA and Y chromosome studies on the genetic distance of Australian Aboriginal genomes from African and other Eurasian ones. A 2018 study using archaeobotany dated evidence of human habitation at Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen) in the Carnarvon Range in the Little Sandy Desert in WA at around 50,000 years (20,000 years earlier than previously thought), and it was shown that human habitation had been continuous at the site since then.[30][31][32]

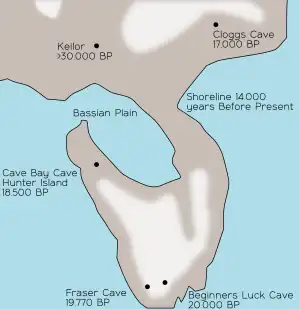

Tasmania, which was connected to the continent by a land bridge, was inhabited at least 30,000 years ago.[33][34] Others have claimed that some sites are up to 60,000 years old, but these claims are not universally accepted.[35] Palynological evidence from South Eastern Australia suggests an increase in fire activity dating from around 120,000 years ago. This has been interpreted as representing human activity, but the dating of the evidence has been strongly challenged.[36]

Migration routes and waves

A 2021 study by researchers at the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage has mapped the likely migration routes of the peoples as they moved across the Australian continent to its southern reaches of what is now Tasmania, but back then part of the mainland. The modelling is based on data from archaeologists, anthropologists, ecologists, geneticists, climatologists, geomorphologists, and hydrologists, and it is intended to compare the modelling with the oral histories of Aboriginal peoples, including Dreaming stories, as well as Australian rock art and linguistic features of the many Aboriginal languages. The routes, dubbed "superhighways" by the authors, are similar to current highways and stock routes in Australia. Lynette Russell of Monash University sees the new model as a starting point for collaboration with Aboriginal people to help uncover their history. The new models suggest that the first people may have first landed in the Kimberley region in what is now Western Australia about 60,000 years ago, and had settled across the continent within 6,000 years.[37][38]

Phylogenetic data suggests that an early Eastern Eurasian lineage trifurcated somewhere in eastern South Asia, and gave rise to Aboriginal Australians, Papuans, the Andamanese, the AASI, as well as East/Southeast Asians, although Papuans may have also received some gene flow from an earlier group (xOoA), around 2%,[39] next to additional archaic admixture in the Sahul region.[40][41]

According to one study, Papuans could have either formed from a mixture between an East Eurasian lineage and lineage basal to West and East Asians, or as a sister lineage of East Asians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution.[42]

A Holocene hunter-gatherer sample (Leang_Panninge) from South Sulawesi was found to be genetically in between Basal-East-Asian and Australo-Papuans. The sample could be modeled as ~50% Papuan-related and ~50% Basal-East Asian-related (Andamanese Onge or Tianyuan). The authors concluded that Basal-East Asian ancestry was far more widespread and the peopling of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania was more complex than previously anticipated.[43][44][45]

It is unknown how many populations settled in Australia prior to European colonisation. Both "trihybrid" and single-origin hypotheses have received extensive discussion.[46] Keith Windschuttle, known for his belief that Aboriginal pre-history has become politicised, argues that the assumption of a single origin is tied into ethnic solidarity, and multiple entry was suppressed because it could be used to justify white seizure of Aboriginal lands,[47] but this hypothesis is not supported by scientific studies.

Changes c.4000 years ago

Human genomic differences are being studied to find possible answers, but there is still insufficient evidence to distinguish a "wave invasion model" from a "single settlement" one.[48]

A 2012 paper by Alan J. Redd et al. on the topic of migration from India around 4,000 years ago notes that the indicated influx period corresponds to the timing of various other changes, specifically mentioning "The divergence times reported here correspond with a series of changes in the Australian anthropological record between 5,000 years ago and 3,000 years ago, including the introduction of the dingo; the spread of the Australian Small Tool tradition; the appearance of plant-processing technologies, especially complex detoxification of cycads; and the expansion of the Pama-Nyungan language over seven-eighths of Australia". Although previously linked to the pariah dogs of India, recent testing of the mitochondrial DNA of dingoes shows a closer connection to the dogs of Eastern Asia and North America, suggesting an introduction as a result of the Austronesian expansion from Southern China to Timor over the last 5,000 years.[48] A 2007 finding of kangaroo ticks on the pariah dogs of Thailand suggested that this genetic expansion may have been a two-way process.[49]

The dingo reached Australia about 4,000 years ago, and around the same time there were changes in language, with the Pama-Nyungan language family spreading over most of the mainland, and stone tool technology, with the use of smaller tools. Human contact has thus been inferred, and genetic data of two kinds have been proposed to support a gene flow from India to Australia: firstly, signs of South Asian components in Aboriginal Australian genomes, reported on the basis of genome-wide SNP data; and secondly, the existence of a Y chromosome (male) lineage, designated haplogroup C∗, with the most recent common ancestor around 5,000 years ago.[50] The first type of evidence comes from a 2013 study by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology using large-scale genotyping data from a pool of Aboriginal Australians, New Guineans, island Southeast Asians and Indians. It found that the New Guinea and Mamanwa (Philippines area) groups diverged from the Aboriginal about 36,000 years ago (and supporting evidence that these populations are descended from migrants taking an early "southern route" out of Africa, before other groups in the area), and also that the Indian and Australian populations mixed well before European contact, with this gene flow occurring during the Holocene (c.4,230 years ago).[51] The researchers had two theories for this: either some Indians had contact with people in Indonesia who eventually transferred those genes from India to Aboriginal Australians, or that a group of Indians migrated all the way from India to Australia and intermingled with the locals directly.[52][53]

However, a 2016 study in Current Biology by Anders Bergström et al. excluded the Y chromosome as providing evidence for recent gene flow from India into Australia. The study authors sequenced 13 Aboriginal Australian Y chromosomes using recent advances in gene sequencing technology, investigating their divergence times from Y chromosomes in other continents, including comparing the haplogroup C chromosomes. The authors concluded that, although this does not disprove the presence of any Holocene gene flow or non-genetic influences from South Asia at that time, and the appearance of the dingo does provide strong evidence for external contacts, the evidence overall is consistent with a complete lack of gene flow, and points to indigenous origins for the technological and linguistic changes. Gene flow across the island-dotted 150-kilometre (93 mi)-wide Torres Strait, is both geographically plausible and demonstrated by the data, although at this point it could not be determined from this study when within the last 10,000 years it may have occurred - newer analytical techniques have the potential to address such questions.[50]

Advent of fire farming and megafauna extinctions

Archaeological evidence from ash deposits in the Coral Sea indicates that fire was already a significant part of the Australian landscape over 100,000 years BP.[54] Over the past 70,000 years it became more frequent with one explanation being the use by hunter-gatherers as a tool to drive game, to produce a green flush of new growth to attract animals, and to open up impenetrable forest. In The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia, Bill Gammage claims that dense forest became more open sclerophyll forest, open forest became grassland and fire-tolerant species became more predominant: in particular, eucalyptus, acacia, banksia, casuarina and grasses.[55]

The changes to the fauna were even more dramatic: the megafauna, species significantly larger than humans, disappeared, and many of the smaller species disappeared too. All told, about 60 different vertebrates became extinct, including the genus Diprotodon (very large marsupial herbivores that looked rather like hippos), several large flightless birds, carnivorous kangaroos, Wonambi naracoortensis, a five-metre snake, a five-metre lizard and Meiolania.[56]

The direct cause of the mass extinctions is uncertain: it may have been fire, hunting, climate change or a combination of all or any of these factors. The degree of human agency in these extinctions is still a matter of discussion.[57][58] With no large herbivores to keep the understorey vegetation down and rapidly recycle soil nutrients with their dung, fuel build-up became more rapid and fires burned hotter, further changing the landscape. Against this theory is the evidence that in fact careful seasonal fires from Aboriginal land management practices reduced fuel loads, and prevented wildfires like those seen since European colonisation.[59]

The period from 18,000 to 15,000 BP saw increased aridity of the continent with lower temperatures and less rainfall than currently prevails. Between 16,000 and 14,000 years BP the rate of sea level rise was most rapid rising about 15 metres in 300 years according to Peter D. Ward.[60] At the end of the Pleistocene, roughly 13,000 years ago, the Torres Strait connection, the Bassian Plain between modern-day Victoria and Tasmania, and the link from Kangaroo Island began disappearing under the rising sea. Various Aboriginal groups seem to have preserved oral histories of the Flandrian sea level rise, in the Kimberley and Northern Australia and also in the isolation of Rottnest Island from the southwestern Western Australian coast 12,000 years ago. The finding of a chert deposit in the strait between the island and the mainland, and the use of chert as a predominant rock in the lithic industries of the region, enables the date to be fairly well established.

From that time on, the Aboriginal Tasmanians were geographically isolated. By 9,000 years BP small islands in Bass Strait, as well as Kangaroo Island were no longer inhabited.

Linguistic and genetic evidence shows that there has been long-term contact between Australians in the far north and the Austronesian people of modern-day New Guinea and the islands, but that this appears to have been mostly trade with a little intermarriage, as opposed to direct colonisation. Macassan praus are also recorded in the Aboriginal stories from Broome to the Gulf of Carpentaria, and there were some semi-permanent settlements established, and cases of Aboriginal settlers finding a home in Indonesia.

Culture and technology

The last 5,000 years were characterised by a general amelioration of the climate and an increase in temperature and rainfall and the development of a sophisticated tribal social structure.[61] The main items of trade were songs and dances, along with flint, precious stones, shells, seeds, spears, food items, etc.

Although it was traditionally thought that Australian Aboriginal people were exclusively hunter-gathers, as reported by Captain Cook, recent research strongly suggests that forms of taro ("yam") were planted and grown on land prepared for the purpose in some areas, and this may have been associated with more settled communities. Despite the presence of agriculture and permanent settlements, "Neolithic" is not usually used with reference to Australian prehistory.[62]

The Pama–Nyungan language family, which extends from Cape York to the southwest, covered all of Australia except for the southeast and Arnhem Land. There was also a marked continuity of religious ideas and stories throughout the country, with some songlines crossing from one side of the continent to the other.

The initiation of young boys and girls into adult knowledge was marked by ceremony and feasting. Initiation rites included female genital mutilation,[63] ritual gang raping,[64] penile subincision.[65]

Behaviour was governed by strict rules regarding responsibilities to and from uncles, aunts, brothers and sisters as well as in-laws. The kinship systems observed by many communities included a division into moieties, with restrictions on intermarrying dictated by the moiety an individual belonged to.[66]

Describing prehistoric Aboriginal culture and society during her 1999 Boyer Lecture, Australian historian and anthropologist Inga Clendinnen explained:

"They [...] developed steepling thought-structures – intellectual edifices so comprehensive that every creature and plant had its place within it. They travelled light, but they were walking atlases, and walking encyclopedias of natural history. [...] Detailed observations of nature were elevated into drama by the development of multiple and multi-level narratives: narratives which made the intricate relationships between these observed phenomena memorable.

These dramatic narratives identified the recurrent and therefore the timeless and the significant within the fleeting and the idiosyncratic. They were also very human, charged with moral significance but with pathos, and with humour, too – after all, the Dreamtime creatures were not austere divinities, but fallible beings who happened to make the world and everything in it while going about their creaturely business. Traditional Aboriginal culture effortlessly fuses areas of understanding which Europeans 'naturally' keep separate: ecology, cosmology, theology, social morality, art, comedy, tragedy – the observed and the richly imagined fused into a seamless whole."[67]

Infanticide (estimated 30% of newborns, often as means of population and family size control, partly to preserve resources and to enable mobility, as only women carried young children)[68] and cannibalism[69] are widely documented in many, but not all regions of the continent.

Political and religious power rested with community elders rather than hereditary chiefs. Disputes were settled communally in accordance with an elaborate system of tribal law. Vendettas and feuds were not uncommon, especially when laws and taboos were broken. Cremation of the dead was practised by 25,000 years ago, possibly before anywhere else on Earth, and early artwork in Koonalda Cave, Nullarbor Plain, has been dated back to 20,000 years ago.[70]

It has been estimated that in 1788 there were approximately half a million Aboriginal Australian people, although other estimates have put the figure as high as a million or more. These populations formed hundreds of distinct cultural and language groups.[71]

Little interest was shown by white settlers in the bulk of the Aboriginal people, and so little is known of their cultures and languages. Diseases decimated some Indigenous populations when they came into contact with the colonialists, and the Frontier Wars wiped out many more. When Cook first claimed New South Wales for Britain in 1770, the native population may have consisted of as many as 600 distinct tribes speaking 200–250 distinct languages and over 600 distinct dialects and sub-dialects.[72][73][74]

Contact outside Australia

Aboriginal people have no cultural memory of living anywhere outside Australia. Nevertheless, the people living along the northern coastline of Australia, in the Kimberley, Arnhem Land, Gulf of Carpentaria and Cape York had encounters with various visitors for many thousands of years. People and traded goods moved freely between Australia and New Guinea up to and even after the eventual flooding of the land bridge by rising sea levels, which was completed about 6,000 years ago.

However, trade and intercourse between the separated lands continued across the newly formed Torres Strait, whose 150 km-wide channel remained readily navigable with the chain of Torres Strait Islands and reefs affording intermediary stopping points. The islands were settled by different seafaring Melanesian cultures such as the Torres Strait Islanders over 2500 years ago, and cultural interactions continued via this route with the Aboriginal people of northeast Australia.

Indonesian "Bajau" fishermen from the Spice Islands (e.g. Banda) have fished off the coast of Australia for hundreds of years. Macassan traders from Sulawesi regularly visited the coast of northern Australia to fish for trepang, an edible sea cucumber to trade with the Chinese since at least the early 18th century.

There was a high degree of cultural exchange, evidenced in Aboriginal rock and bark paintings, the introduction of technologies such as dug-out canoes and items such as tobacco and tobacco pipes, Macassan words in Aboriginal languages (e.g. Balanda for white person), and descendants of Malay people in Australian Aboriginal communities and vice versa, as a result of intermarriage and migration.[75]

The myths of the people of Arnhem Land have preserved accounts of the trepang-catching, rice-growing Baijini people, who, according to the myths, were in Australia in the earliest times, before the Macassans. The Baijini have been variously interpreted by modern researchers as a different group of presumably South East Asian people, such as Bajau visitors to Australia who may have visited Arnhem Land before the Macassans,[76][77] as a mythological reflection of the experiences of some Yolŋu people who have travelled to Sulawesi with the Macassans and came back,[78] or, in more fringe views, even as visitors from China.[79]

Possible link to east Africa

In 1944, a small number of copper coins with Arabic inscriptions were discovered on a beach in Jensen Bay on Marchinbar Island, part of the Wessel Islands of the Northern Territory. These coins were later identified as from the Kilwa Sultanate of east Africa. Only one such coin had ever previously been found outside east Africa (unearthed during an excavation in Oman). The inscriptions on the Jensen Bay coins identify a ruling Sultan of Kilwa, but it is unclear whether the ruler was from the 10th century or the 14th century. This discovery has been of interest to those historians who believe it likely that people made landfall in Australia or its offshore islands before the first generally accepted such discovery, by the Dutch sailor Willem Janszoon in 1606.[80]

See also

- Australian Aboriginal sacred site

- Australian archaeology

- Dreamtime, Aboriginal mythology about Australian prehistory

- European maritime exploration of Australia

- Juukan Gorge caves, destroyed in May 2020

- Lake Mungo remains

- Ten Canoes, a 2006 film about Australian prehistory

References

- ↑ Mahuika, Nepia (14 November 2019). Rethinking Oral History and Tradition. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190681685.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-068168-5.

- ↑ Wyrwoll, Karl-Heinz (11 January 2012). "How Aboriginal burning changed Australia's climate". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Williams, Robbie (21 June 2023). "Before the colonists came, we burned small and burned often to avoid big fires. It's time to relearn cultural burning". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Gammage, Bill (October 2011). The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Allen & Unwin. pp. 281–304. ISBN 978-1-74237-748-3.

- ↑ Gammage, Bill (19 September 2023). "Colonists upended Aboriginal farming, growing grain and running sheep on rich yamfields, and cattle on arid grainlands". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Moore, Robyn (2 August 2020). "Secondary school textbooks teach our kids the myth that Aboriginal Australians were nomadic hunter-gatherers". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Bates, Badger; Westaway, Michael; Jackson, Sue (15 December 2022). "Aboriginal people have spent centuries building in the Darling River. Now there are plans to demolish these important structures". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Clark, Anna (31 August 2023). "Friday essay: traps, rites and kurrajong twine – the incredible ingenuity of Indigenous fishing knowledge". The Conversation. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Wright, Tony (12 July 2019). "Even dynamite could not destroy the people of the Budj Bim stones". The Age. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ Thomas, Northcote W. (1906). Natives of Australia.

- ↑ Wahlquist, Calla (5 September 2016). "Evidence of 9,000-year-old stone houses found on Australian island". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ "Rethinking Indigenous Australia's agricultural past". ABC Radio National. 15 May 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ↑ Griffiths, Billy (2018). Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia. Black Inc. pp. 288–289. ISBN 9781760640446.

- 1 2 Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; et al. (19 July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago" (PDF). Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. Bibcode:2017Natur.547..306C. doi:10.1038/nature22968. hdl:2440/107043. PMID 28726833. S2CID 205257212.

- 1 2 Lourandos 1997, p. 80.

- ↑ Lourandos 1997, p. 81.

- ↑ Rupert Gerritsen (2011) Beyond the Frontier: Explorations in Ethnohistory, Batavia Online Publishing: Canberra, pp. 70–103. ISBN 978-0-9872141-4-0.

- ↑ Ron Laidlaw "Aboriginal Society before European settlement" in Tim Gurry (ed.) (1984) The European Occupation. Heinemann Educational Australia, Richmond, p. 40. ISBN 0-85859-250-9.

- ↑ Scott Cane; First Footprints - the epic story of the first Australians; Allen & Unwin; 2013; ISBN 978 1 74331 493 7; pp. 25-26

- ↑ Hiscock, Peter (2008). Archaeology of Ancient Australia. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33811-0.

- ↑ Gibbons, Ann (20 July 2017). "The first Australians arrived early". Science. 357 (6348): 238–239. Bibcode:2017Sci...357..238G. doi:10.1126/science.357.6348.238. PMID 28729491.

- ↑ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2020), Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond, Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199812790 / ISBN 9780199812776

- ↑ Macey, Richard (2007). "Settlers' history rewritten: go back 30,000 years". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ↑ Blainey, Geoffrey (2004). A Very Short History of the World. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-300559-9.

- ↑ Stockton, Eugene D.; Nanson, Gerald C. (April 2004). "Cranebrook Terrace Revisited". Archaeology in Oceania. 39 (1): 59–60. doi:10.1002/j.1834-4453.2004.tb00560.x. JSTOR 40387277.

- ↑ Pierce, R. H.; Barbetti, Mike (2014). "A 38,000-year-old archaeological site at Upper Swan, Western Australia". Archaeology in Oceania. 16 (3).

- ↑ "Australia colonized earlier than previously thought?". Stone Pages. Archaeo News. 24 July 2003.

The West Australian (19 July 2003)

- ↑ Hesp, Patrick A.; Murray-Wallace, Colin V.; Dortch, C. E. (1999). "Aboriginal occupation on Rottnest Island, Western Australia, provisionally dated by Aspartic Acid Racemisation assay of land snails to greater than 50 ka". Australian Archaeology. 49 (1): 7–12. doi:10.1080/03122417.1999.11681647.

- ↑ Dortch, Charles (23 June 2003). The West Australian.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ McDonald, Josephine; Reynen, Wendy; Petchey, Fiona; Ditchfield, Kane; Byrne, Chae; Vannieuwenhuyse, Dorcas; Leopold, Matthias; Veth, Peter (September 2018). "Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen): A new chronology for the oldest site in Australia's Western Desert". PLOS ONE. 13 (9). e0202511. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1302511M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0202511. PMC 6145509. PMID 30231025 – via ResearchGate.

The re-excavation of Karnatukul (Serpent's Glen) has provided evidence for the human occupation of the Australian Western Desert to before 47,830 cal. BP (modelled median age). This new sequence is 20,000 years older than the previous known age for occupation at this site

- ↑ McDonald, Jo; Veth, Peter (2008). "Rock-art of the Western Desert and Pilbara: Pigment dates provide new perspectives on the role of art in the Australian arid zone". Australian Aboriginal Studies (2008/1): 4–21 – via ResearchGate.

- ↑ McDonald, Jo (2 July 2020). "Serpents Glen (Karnatukul): New Histories for Deep time Attachment to Country in Australia's Western Desert". Bulletin of the History of Archaeology. 30 (1). doi:10.5334/bha-624. ISSN 2047-6930. S2CID 225577563.

- ↑ Lourandos 1997, pp. 84–87.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas (8 May 2007). "From DNA Analysis, Clues to a Single Australian Migration". The New York Times.

- ↑ Lourandos 1997, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Lourandos 1997, p. 88.

- ↑ Morse, Dana (30 April 2021). "Researchers demystify the secrets of ancient Aboriginal migration across Australia". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ↑ Crabtree, S. A.; White, D. A.; et al. (29 April 2021). "Landscape rules predict optimal superhighways for the first peopling of Sahul". Nature Human Behaviour. 5 (10): 1303–1313. doi:10.1038/s41562-021-01106-8. PMID 33927367. S2CID 233458467. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ↑ "Almost all living people outside of Africa trace back to a single migration more than 50,000 years ago". www.science.org. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ↑ Yang, Melinda A. (6 January 2022). "A genetic history of migration, diversification, and admixture in Asia". Human Population Genetics and Genomics. 2 (1): 1–32. doi:10.47248/hpgg2202010001. ISSN 2770-5005.

- ↑ Genetics and material culture support repeated expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a population hub out of Africa, Vallini et al. 2022 (April 4, 2022) Quote: "Taken together with a lower bound of the final settlement of Sahul at 37 kya it is reasonable to describe Papuans as either an almost even mixture between East-Eurasians and a lineage basal to West and East-Eurasians which occurred sometimes between 45 and 38kya, or as a sister lineage of East-Eurasians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution. We here chose to parsimoniously describe Papuans as a simple sister group of Tianyuan, cautioning that this may be just one out of six equifinal possibilities."

- ↑ Genetics and material culture support repeated expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a population hub out of Afri, Vallini et al. 2021 (October 15, 2021) Quote: "Taken together with a lower bound of the final settlement of Sahul at 37 kya (the date of the deepest population splits estimated by 1) it is reasonable to describe Papuans as either an almost even mixture between East Asians and a lineage basal to West and East Asians occurred sometimes between 45 and 38kya, or as a sister lineage of East Asians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution. "

- ↑ Genomic insights into the human population history of Australia and New Guinea, University of Cambridge, Bergström et al. 2018

- ↑ Genetics and material culture support repeated expansions into Paleolithic Eurasia from a population hub out of Afri, Vallini et al. 2021 (October 15, 2021) Quote: "Taken together with a lower bound of the final settlement of Sahul at 37 kya (the date of the deepest population splits estimated by 1) it is reasonable to describe Papuans as either an almost even mixture between East Asians and a lineage basal to West and East Asians occurred sometimes between 45 and 38kya, or as a sister lineage of East Asians with or without a minor basal OoA or xOoA contribution."

- ↑ Carlhoff, Selina; Duli, Akin; Nägele, Kathrin; Nur, Muhammad; Skov, Laurits; Sumantri, Iwan; Oktaviana, Adhi Agus; Hakim, Budianto; Burhan, Basran; Syahdar, Fardi Ali; McGahan, David P. (2021). "Genome of a middle Holocene hunter-gatherer from Wallacea". Nature. 596 (7873): 543–547. Bibcode:2021Natur.596..543C. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03823-6. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 8387238. PMID 34433944.

The qpGraph analysis confirmed this branching pattern, with the Leang Panninge individual branching off from the Near Oceanian clade after the Denisovan gene flow, although with the most supported topology indicating around 50% of a basal East Asian component contributing to the Leang Panninge genome (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Figs. 7–11).

- ↑ Windschuttle, Keith; Gillin, Tim (June 2002). "The extinction of the Australian pygmies". Keith Windschuttle (The Sydney Line). Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 2 November 2007.

- ↑ Windschuttle, Keith (2002). The Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen's Land 1803-1847. Macleay Press.

- 1 2 Peter Savolainen, Thomas Leitner, Alan N. Wilton, Elizabeth Matisoo-Smith, and Joakim Lundeberg (2004),"A detailed picture of the origin of the Australian dingo, obtained from the study of mitochondrial DNA"(Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004 Aug 17; 101(33): 12387–12390.

- ↑ Alan J. Redd; June Roberts-Thomson; Tatiana Karafet; Michael Bamshad; Lynn B. Jorde; J.M. Naidu; Bruce Walsh; Michael F. Hammer (16 April 2002). "Gene Flow from the Indian Subcontinent to Australia: Evidence from the Y Chromosome". Current Biology. Orlando, Florida, US: Elsevier Science. 12 (8): 673–677. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(02)00789-3. PMID 11967156. S2CID 7752658.

- 1 2 Bergström, Anders; Nagle, Nano; Chen, Yuan; McCarthy, Shane; Pollard, Martin O.; Ayub, Qasim; Wilcox, Stephen; Wilcox, Leah; Oorschot, Roland A.H. van; McAllister, Peter; Williams, Lesley; Xue, Yali; Mitchell, R. John; Tyler-Smith, Chris (21 March 2016). "Deep Roots for Aboriginal Australian Y Chromosomes". Current Biology. 26 (6): 809–813. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.01.028. PMC 4819516. PMID 26923783. An open access article under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ↑ Pugach, Irina; Delfin, Frederick; Gunnarsdóttir, Ellen; Kayser, Manfred; Stoneking, Mark (29 January 2013). "Genome-wide data substantiate Holocene gene flow from India to Australia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (5): 1803–1808. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1803P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211927110. PMC 3562786. PMID 23319617.

- ↑ Sanyal, Sanjeev (2016). The ocean of churn: how the Indian Ocean shaped human history. Gurgaon, Haryana, India. p. 59. ISBN 9789386057617. OCLC 990782127.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ MacDonald, Anna (15 January 2013). "Research shows ancient Indian migration to Australia". ABC News.

- ↑ Clarke, Robin L. (1983), "Pollen and Charcoal Evidence for the Effects of Aboriginal Burning on Vegetation in Australia" (Archaeology in Oceania, Vol. 18, No. 1983).

- ↑ Gammage, Bill (2011) "The Biggest Estate on Earth (Allen and Unwin).

- ↑ Roberts, R.G., Flannery, T et al. (2001) "New Ages for the Last Australian Megafauna: continent wide extinction about 46,000 years ago" (Science, Vol. 292, 8 June 2001).

- ↑ Rowan, John; Faith, J. T. (2019). "The Paleoecological Impact of Grazing and Browsing: Consequences of the Late Quaternary Large Herbivore Extinctions". In Gordon, Iain J.; Prins, Herbert H. T. (eds.). The Ecology of Browsing and Grazing II. Ecological Studies. Vol. 239. Springer International Publishing. pp. 61–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-25865-8_3. ISBN 978-3-030-25864-1. S2CID 210622244.

- ↑ Wroe, S. & Field, J. (2006) "A review of the evidence of the human role in the extinction of Australian megafauna and an alternative explanation" (Quaternary Science Reviews, Vol. 25, No. 21-22, Nov 2006).

- ↑ Gammage, Bill (2011), "The Biggest Estate of Earth" (Allen and Unwin).

- ↑ Peter D. Ward, p. 30, The Flooded Earth. Our Future in a World Without Ice Caps, Basic Books, New York, 2010, ISBN 978-0-465-00949-7.

- ↑ John Bern (1979) "Ideology and Domination: towards a reconstruction of Australian Aboriginal social formation" (Oceania, Vol. 50, No. 2, Dec 1979).

- ↑ White, Peter (2006), Revisiting the 'Neolithic Problem' in Australia (PDF), Records of the Western Australian Museum 086–092 (2011) Supplement

- ↑ Joseph, Cathy (1996). "Compassionate Accountability: An Embodied Consideration of Female Genital Mutilation". The Journal of Psychohistory. 24: 12.

- ↑ deMause, Lloyd (2002). The Emotional Life of Nations. New York & London: Karnac. pp. 699, 700. ISBN 1-892746-98-0.

- ↑ Denniston, George C.; Hodges, Frederick Mansfield; Milos, Marilyn Fayre, eds. (1999). Male and female circumcision: medical, legal, and ethical considerations in pediatric practice ; [proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Sexual Mutilations: Medical, Legal, and Ethical Considerations in Pediatric Practice, held August 5-7, 1998, in Oxford, England]. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-306-46131-6.

- ↑ Berndt, R.M & C.H. The World of the First Australians; Aboriginal traditional life, past and present" (Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra).

- ↑ Inga Clendinnen, Boyer Lectures, "Inside the Contact Zone: Part 1", 5 December 1999.

- ↑ Rubinstein, William D. (2004). Genocide: a history (1. ed. publ. in Great Britain ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson Longman. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5.

- ↑ Connor, Michael (2005). The invention of Terra Nullius: historical and legal fictions on the foundation of Australia. Paddington, N.S.W: Macleay Press. pp. 91–94. ISBN 978-1-876492-16-8.

- ↑ Blainey 1976, p. 84.

- ↑ Neil Thomson, p. 153, Indigenous Australia: Indigenous Health in James Jupp (ed.), The Australian people: an encyclopedia of the nation, its people and their Origins, Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-521-80789-1 This article says the likely aboriginal population of Australia in 1788 was around 750,000 or even over a million. There was also a chart from the Australian Bureau of Statistics – Experimental Projections of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population, Canberra, ABS, 1998 – with estimated populations for each state and for Australia as a whole total being 418,841. Epidemics of smallpox occurred in 1789 and 1829–31. The article notes that there is evidence these epidemics traveled several hundred kilometres 'severely depopulating' tribes who had not yet had first contact with Europeans.

- ↑ R. M. W. Dixon, p. 18, The Languages of Australia, Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01785-5 Dixon says "There were around 600 distinct tribes in Australia, speaking between them about 200 different languages."

- ↑ Kerry Mallan, p. 53, Language Politics and Minority Rights in Witold Tulasiewicz, Joseph I. Zajda (eds), Language awareness in the curriculum, James Nicholas Publishers, Albert Park, ISBN 1-875408-21-5 Estimates 200 languages and over 600 dialects in 1788.

- ↑ Harold Koch, p. 23, "An overview of Australian traditional languages" in Gerhard Leitner, Ian G. Malcolm (eds), The habitat of Australia's aboriginal languages: past, present and future. Says that some 250 distinct languages present in 1788.

- ↑ Russell, Denise (2004). "Aboriginal-Makassan interactions in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in northern Australia and contemporary sea rights claims" (PDF). Australian Aboriginal Studies. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (1): 6–7. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ Berndt, Ronald Murray; Berndt, Catherine Helen (1954). Arnhem Land: its history and its people. Volume 8 of Human relations area files: Murngin. F. W. Cheshire. p. 34.

- ↑ Berndt 2005, p. 55.

- ↑ Swain 1993, p. 170.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1971). Science and civilisation in China. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 538. ISBN 0-521-07060-0.

- ↑ Jonathan Gornall (29 May 2013). "Were the African coins found in Australia from a wrecked Arab dhow?". The National. Archived from the original on 6 July 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

Bibliography

- Frankel, David (2017). Between the Murray and the Sea. Aboriginal Archaeology in Southeastern Australia. Sydney University Press. ISBN 978-1-7433-2552-0.

- Blainey, Geoffrey (1976). Triumph of the Nomads: History of Ancient Australia. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-02423-0.

- Lourandos, Harry (1997). Continent of Hunter-Gatherers: New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-35946-7.

- Mulvaney, D. J. (1969). The Prehistory of Australia. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Mulvaney, John; Kamminga, Johan (1999). Prehistory of Australia. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86448-950-7.

- Isaacs, Jennifer (2006). Australian Dreaming: 40,000 Years of Aboriginal History. New Holland. ISBN 9781741102581.

- Berndt, Ronald M. (2005) [1952]. Djanggawul: An Aboriginal Religious Cult of North-Eastern Arnhem Land. Routledge. ISBN 041533022X.

- Swain, Tony (1993). A place for strangers: towards a history of Australian Aboriginal being. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44691-4.

![]() This article incorporates text by Anders Bergström et al. available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Anders Bergström et al. available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

External links

- Timeline of pre-contact Australia Australian Museum